Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires (/ˌbweɪnəs ˈɛəriːz/ or /-ˈaɪrɪs/;[9] Spanish pronunciation: [ˈbwenos ˈajɾes])[10] is the capital and largest city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the estuary of the Río de la Plata, on the South American continent's southeastern coast. "Buenos Aires" can be translated as "fair winds" or "good airs", but the former was the meaning intended by the founders in the 16th century, by the use of the original name "Real de Nuestra Señora Santa María del Buen Ayre", named after the Madonna of Bonaria in Sardinia. The Greater Buenos Aires conurbation, which also includes several Buenos Aires Province districts, constitutes the fourth-most populous metropolitan area in the Americas, with a population of around 15.6 million.[7]

City of Buenos Aires Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires | |

|---|---|

| Autonomous City of Buenos Aires | |

From top, left to right: view of the Business District, the Palace of the Congress, the Bridge of the Women, the Cabildo, the Casa Rosada, the Caminito alley in La Boca, the Obelisco on the intersection of 9 de Julio and Corrientes avenues and the Metropolitan Cathedral. | |

| Nickname(s): | |

City of Buenos Aires Location in Argentina  City of Buenos Aires City of Buenos Aires (South America) | |

| Coordinates: 34°36′12″S 58°22′54″W | |

| Country | |

| Established | 2 February 1536 (by Pedro de Mendoza) 11 June 1580 (by Juan de Garay) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Autonomous city |

| • Body | City Legislature |

| • Mayor | Horacio Rodríguez Larreta (PRO) |

| • Senators | Martín Lousteau (UCR), Guadalupe Tagliaferri (PRO), Mariano Recalde (FdT) |

| Area | |

| • Capital city and autonomous city | 203 km2 (78 sq mi) |

| • Land | 203 km2 (78.5 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,758 km2 (1,837 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 25 m (82 ft) |

| Population (2010 census)[7] | |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Urban | 2,891,082 |

| • Metro | 15,594,428 |

| Demonyms | porteño (m), porteña (f) |

| Time zone | UTC−3 (ART) |

| Area code(s) | 011 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.867 Very High (1st)[8] |

| Website | www |

The city of Buenos Aires is neither part of Buenos Aires Province nor the Province's capital; rather, it is an autonomous district. In 1880, after decades of political infighting, Buenos Aires was federalized and removed from Buenos Aires Province.[11] The city limits were enlarged to include the towns of Belgrano and Flores; both are now neighborhoods of the city. The 1994 constitutional amendment granted the city autonomy, hence its formal name of Autonomous City of Buenos Aires (Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires; "CABA"). Its citizens first elected a chief of government (i.e. mayor) in 1996; previously, the mayor was directly appointed by the President of the Republic.

Buenos Aires' quality of life was ranked 91st in the world in 2018, being one of the best in Latin America.[12][13] In 2012, it was the most visited city in South America, and the second-most visited city of Latin America (behind Mexico City).[14]

It is known for its preserved Eclectic European architecture[15] and rich cultural life.[16] Buenos Aires held the 1st Pan American Games in 1951 and was the site of two venues in the 1978 FIFA World Cup. Most recently, Buenos Aires hosted the 2018 Summer Youth Olympics[17] and the 2018 G20 summit.[18]

Buenos Aires is a multicultural city, being home to multiple ethnic and religious groups. Several languages are spoken in the city in addition to Spanish, contributing to its culture and the dialect spoken in the city and in some other parts of the country. This is because since the 19th century the city, and the country in general, has been a major recipient of millions of immigrants from all over the world, making it a melting pot where several ethnic groups live together and being considered one of the most diverse cities of the Americas.[19]

Etymology

.jpg)

It is recorded under the Aragonese's archives that Catalan missionaries and Jesuits arriving in Cagliari (Sardinia) under the Crown of Aragon, after its capture from the Pisans in 1324 established their headquarters on top of a hill that overlooked the city.[20] The hill was known to them as Bonaira (or Bonaria in Sardinian language), as it was free of the foul smell prevalent in the old city (the castle area), which is adjacent to swampland. During the Cagliari's siege, the Catalans built a sanctuary to the Virgin Mary on top of the hill. In 1335, King Alfonso the Gentle donated the church to the Mercedarians, who built an abbey that stands to this day. In the years after that, a story circulated, claiming that a statue of the Virgin Mary was retrieved from the sea after it miraculously helped to calm a storm in the Mediterranean Sea. The statue was placed in the abbey. Spanish sailors, especially Andalusians, venerated this image and frequently invoked the "Fair Winds" to aid them in their navigation and prevent shipwrecks. A sanctuary to the Virgin of Buen Ayre would be later erected in Seville.[20]

In the first foundation of Buenos Aires, Spanish sailors arrived thankfully in the Río de la Plata by the blessings of the "Santa Maria de los Buenos Aires", the "Holy Virgin Mary of the Good Winds" who was said to have given them the good winds to reach the coast of what is today the modern city of Buenos Aires.[21] Pedro de Mendoza called the city "Holy Mary of the Fair Winds", a name suggested by the chaplain of Mendoza's expedition – a devotee of the Virgin of Buen Ayre – after the Madonna of Bonaria from Sardinia[22] (which is still to this day the patroness of the Mediterranean island[23]). Mendoza's settlement soon came under attack by indigenous people, and was abandoned in 1541.[21]

For many years, the name was attributed to a Sancho del Campo, who is said to have exclaimed: How fair are the winds of this land!, as he arrived. But Eduardo Madero, in 1882 after conducting extensive research in Spanish archives, ultimately concluded that the name was indeed closely linked with the devotion of the sailors to Our Lady of Buen Ayre.[24]

A second (and permanent) settlement was established in 1580 by Juan de Garay, who sailed down the Paraná River from Asunción (now the capital of Paraguay). Garay preserved the name originally chosen by Mendoza, calling the city Ciudad de la Santísima Trinidad y Puerto de Santa María del Buen Aire ("City of the Most Holy Trinity and Port of Saint Mary of the Fair Winds"). The short form "Buenos Aires" became common usage during the 17th century.[25]

The usual abbreviation for Buenos Aires in Spanish is Bs.As.[26] It is common as well to refer to it as "B.A." or "BA".[27] When referring specifically to the autonomous city, it is very common to colloquially call it "Capital" in Spanish. Since the autonomy obtained in 1994, it has been called "CABA" (per Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Autonomous City of Buenos Aires).

While "BA" is used more by expats residing in the city, the locals more often use the abbreviation "Baires", in one word.

History

Colonial times

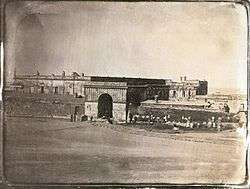

Seaman Juan Díaz de Solís, navigating in the name of Spain, was the first European to reach the Río de la Plata in 1516. His expedition was cut short when he was killed during an attack by the native Charrúa tribe in what is now Uruguay.

The city of Buenos Aires was first established as Ciudad de Nuestra Señora Santa María del Buen Ayre[2] (literally "City of Our Lady Saint Mary of the Fair Winds") after Our Lady of Bonaria (Patroness Saint of Sardinia) on 2 February 1536 by a Spanish expedition led by Pedro de Mendoza. The settlement founded by Mendoza was located in what is today the San Telmo district of Buenos Aires, south of the city centre.

More attacks by the indigenous people forced the settlers away, and in 1542 the site was abandoned.[28][29] A second (and permanent) settlement was established on 11 June 1580 by Juan de Garay, who arrived by sailing down the Paraná River from Asunción (now the capital of Paraguay). He dubbed the settlement "Santísima Trinidad" and its port became "Puerto de Santa María de los Buenos Aires."[25]

From its earliest days, Buenos Aires depended primarily on trade. During most of the 17th century, Spanish ships were menaced by pirates, so they developed a complex system where ships with military protection were dispatched to Central America in a convoy from Seville (the only port allowed to trade with the colonies) to Lima, Peru, and from it to the inner cities of the viceroyalty. Because of this, products took a very long time to arrive in Buenos Aires, and the taxes generated by the transport made them prohibitive. This scheme frustrated the traders of Buenos Aires, and a thriving informal yet accepted by the authorities contraband industry developed inside the colonies and with the Portuguese. This also instilled a deep resentment among porteños towards the Spanish authorities.[2]

Sensing these feelings, Charles III of Spain progressively eased the trade restrictions and finally declared Buenos Aires an open port in the late 18th century. The capture of Porto Bello by British forces also fueled the need to foster commerce via the Atlantic route, to the detriment of Lima-based trade. One of his rulings was to split a region from the Viceroyalty of Perú and create instead the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, with Buenos Aires as the capital. However, Charles's placating actions did not have the desired effect, and the porteños, some of them versed in the ideology of the French Revolution, became even more convinced of the need for independence from Spain.

War of Independence

.jpg)

During the British invasions of the Río de la Plata, British forces attacked Buenos Aires twice. In 1806 the British successfully invaded Buenos Aires, but an army from Montevideo led by Santiago de Liniers defeated them. In the brief period of British rule, the viceroy Rafael Sobremonte managed to escape to Córdoba and designated this city as capital. Buenos Aires became the capital again after its liberation, but Sobremonte could not resume his duties as viceroy. Santiago de Liniers, chosen as new viceroy, prepared the city against a possible new British attack and repelled the attempted invasion of 1807. The militarization generated in society changed the balance of power favorably for the criollos (in contrast to peninsulars), as well as the development of the Peninsular War in Spain. An attempt by the peninsular merchant Martín de Álzaga to remove Liniers and replace him with a Junta was defeated by the criollo armies. However, by 1810 it would be those same armies who would support a new revolutionary attempt, successfully removing the new viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros. This is known as the May Revolution, which is now celebrated as a national holiday. This event started the Argentine War of Independence, and many armies left Buenos Aires to fight the diverse strongholds of royalist resistance, with varying levels of success. The government was held first by two Juntas of many members, then by two triumvirates, and finally by a unipersonal office, the Supreme Director. Formal independence from Spain was declared in 1816, at the Congress of Tucumán. Buenos Aires managed to endure the whole Spanish American wars of independence without falling again under royalist rule.

Historically, Buenos Aires has been Argentina's main venue of liberal, free-trading and foreign ideas, while many of the provinces, especially those to the north-west, advocated a more nationalistic and Catholic approach to political and social issues. Much of the internal tension in Argentina's history, starting with the centralist-federalist conflicts of the 19th century, can be traced back to these contrasting views. In the months immediately following the 25 May Revolution, Buenos Aires sent a number of military envoys to the provinces with the intention of obtaining their approval. Many of these missions ended in violent clashes, and the enterprise fuelled tensions between the capital and the provinces.

In the 19th century the city was blockaded twice by naval forces: by the French from 1838 to 1840, and later by an Anglo-French expedition from 1845 to 1848. Both blockades failed to force the city into submission, and the foreign powers eventually desisted from their demands.

19th and 20th century

During most of the 19th century, the political status of the city remained a sensitive subject. It was already the capital of Buenos Aires Province, and between 1853 and 1860 it was the capital of the seceded State of Buenos Aires. The issue was fought out more than once on the battlefield, until the matter was finally settled in 1880 when the city was federalized and became the seat of government, with its mayor appointed by the president. The Casa Rosada became the seat of the president.[25]

Health conditions in poor areas were negative, with high rates of tuberculosis. Public-health physicians and politicians typically blamed both the poor themselves and their ramshackle tenement houses (conventillos) for the spread of the dreaded disease. People ignored public-health campaigns to limit the spread of contagious diseases, such as the prohibition of spitting on the streets, the strict guidelines to care for infants and young children, and quarantines that separated families from ill loved ones.[30]

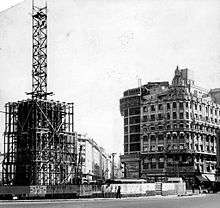

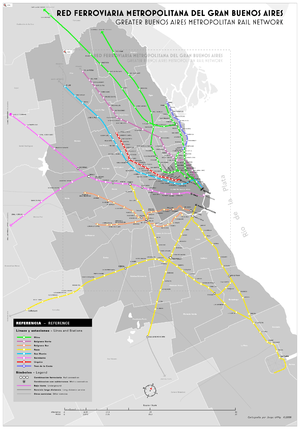

In addition to the wealth generated by the Buenos Aires Customs and the fertile pampas, railroad development in the second half of the 19th century increased the economic power of Buenos Aires as raw materials flowed into its factories. A leading destination for immigrants from Europe, particularly Italy and Spain, from 1880 to 1930 Buenos Aires became a multicultural city that ranked itself with the major European capitals. The Colón Theater became one of the world's top opera venues, and the city became the regional capital of radio, television, cinema, and theatre. The city's main avenues were built during those years, and the dawn of the 20th century saw the construction of South America's tallest buildings and its first underground system. A second construction boom, from 1945 to 1980, reshaped downtown and much of the city.

Buenos Aires also attracted migrants from Argentina's provinces and neighboring countries. Shanty towns (villas miseria) started growing around the city's industrial areas during the 1930s, leading to pervasive social problems and social contrasts with the largely upwardly-mobile Buenos Aires population. These laborers became the political base of Peronism, which emerged in Buenos Aires during the pivotal demonstration of 17 October 1945, at the Plaza de Mayo.[31] Industrial workers of the Greater Buenos Aires industrial belt have been Peronism's main support base ever since, and Plaza de Mayo became the site for demonstrations and many of the country's political events; on 16 June 1955, however, a splinter faction of the Navy bombed the Plaza de Mayo area, killing 364 civilians (see Bombing of Plaza de Mayo). This was the only time the city was attacked from the air, and the event was followed by a military uprising which deposed President Perón, three months later (see Revolución Libertadora).

In the 1970s the city suffered from the fighting between left-wing revolutionary movements (Montoneros, ERP and F.A.R.) and the right-wing paramilitary group Triple A, supported by Isabel Perón, who became president of Argentina in 1974 after Juan Perón's death.

The March 1976 coup, led by General Jorge Videla, only escalated this conflict; the "Dirty War" resulted in 30,000 desaparecidos (people kidnapped and killed by the military during the years of the junta).[32] The silent marches of their mothers (Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo) are a well-known image of Argentines' suffering during those times. The dictatorship's appointed mayor, Osvaldo Cacciatore, also drew up plans for a network of freeways intended to relieve the city's acute traffic gridlock. The plan, however, called for a seemingly indiscriminate razing of residential areas and, though only three of the eight planned were put up at the time, they were mostly obtrusive raised freeways that continue to blight a number of formerly comfortable neighborhoods to this day.

The city was visited by Pope John Paul II twice, firstly in 1982 and again in 1987; on these occasions gathered some of the largest crowds in the city's history. The return of democracy in 1983 coincided with a cultural revival, and the 1990s saw an economic revival, particularly in the construction and financial sectors.

On 17 March 1992 a bomb exploded in the Israeli Embassy, killing 29 and injuring 242. Another explosion, on 18 July 1994, destroyed a building housing several Jewish organizations, killing 85 and injuring many more, these incidents marked the beginning of Middle Eastern terrorism to South America. Following a 1993 agreement, the Argentine Constitution was amended to give Buenos Aires autonomy and rescinding, among other things, the president's right to appoint the city's mayor (as had been the case since 1880). On 30 June 1996, voters in Buenos Aires chose their first elected mayor (Jefe de Gobierno).

21st century

.jpg)

In 1996, following the 1994 reform of the Argentine Constitution, the city held its first mayoral elections under the new statutes, with the mayor's title formally changed to "Head of Government". The winner was Fernando de la Rúa, who would later become President of Argentina from 1999 to 2001.

De la Rúa's successor, Aníbal Ibarra, won two popular elections, but was impeached (and ultimately deposed on 6 March 2006) as a result of the fire at the República Cromagnon nightclub. Jorge Telerman, who had been the acting mayor, was invested with the office. In the 2007 elections, Mauricio Macri of the Republican Proposal (PRO) party won the second-round of voting over Daniel Filmus of the Frente para la Victoria (FPV) party, taking office on 9 December 2007. In 2011, the elections went to a second round with 60.96% of the vote for PRO, compared to 39.04% for FPV, thus re-electing Macri as mayor of the city with María Eugenia Vidal as deputy mayor.[33]

The 2015 elections were the first to use an electronic voting system in the city, similar to the one used in Salta Province.[34] In these elections held on 5 July 2015, Macri stepped down as mayor and pursue his presidential bid and Horacio Rodríguez Larreta took his place as the mayoral candidate for PRO. In the first round of voting, FPV's Mariano Recalde obtained 21.78% of the vote, while Martín Lousteau of the ECO party obtained 25.59% and Larreta obtained 45.55%, meaning that the elections went to a second round since PRO was unable to secure the majority required for victory.[35] The second round was held on 19 July 2015 and Larreta obtained 51.6% of the vote, followed closely by Lousteau with 48.4%, thus, PRO won the elections for a third term with Larreta as mayor and Diego Santilli as deputy. In these elections, PRO was stronger in the wealthier neighbourhoods of northern Buenos Aires, while ECO was stronger in the south of the city.[36][37]

.jpg) Women's Bridge was designed by Santiago Calatrava.

Women's Bridge was designed by Santiago Calatrava..jpg) View of 9 de Julio Avenue with the Obelisk

View of 9 de Julio Avenue with the Obelisk.jpg) The main financial centre of Buenos Aires

The main financial centre of Buenos Aires

Geography

The city of Buenos Aires lies in the pampa region, except for some zones like the Buenos Aires Ecological Reserve, the Boca Juniors (football) Club "sports city", Jorge Newbery Airport, the Puerto Madero neighborhood and the main port itself; these were all built on reclaimed land along the coasts of the Rio de la Plata (the world's widest river).[38][39][40]

The region was formerly crossed by different streams and lagoons, some of which were refilled and others tubed. Among the most important streams are Maldonado, Vega, Medrano, Cildañez and White. In 1908 many streams were channelled and rectified, as floods were damaging the city's infrastructure. Starting in 1919, most streams were enclosed. Notably, the Maldonado was tubed in 1954, and runs below Juan B. Justo Avenue.

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Buenos Aires has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) with four distinct seasons.[41][42] As a result of maritime influences from the adjoining Atlantic Ocean,[43] the climate is temperate with extreme temperatures being rare.[44] Because the city is located in an area where the Pampero and Sudestada winds pass by,[45] the weather is variable due to these contrasting air masses.[46]

.jpg)

Summers are hot and humid.[44] The warmest month is January, with a daily average of 24.9 °C (76.8 °F).[47] Heat waves are common during summers.[48] However, most heat waves are of short duration (less than a week) and are followed by the passage of the cold, dry Pampero wind which brings violent and intense thunderstorms followed by cooler temperatures.[46][49] The highest temperature ever recorded was 43.3 °C (110 °F) on 29 January 1957.[50]

Winters are cool with mild temperatures during the day and chilly nights.[44] Highs during the season average 16.3 °C (61.3 °F) while lows average 8.1 °C (46.6 °F).[51] Relative humidity averages in the upper 70s%, which means the city is noted for moderate-to-heavy fogs during autumn and winter.[52] July is the coolest month, with an average temperature of 11.0 °C (51.8 °F).[47] Cold spells originating from Antarctica occur almost every year, and can persist for several days.[51] Occasionally, warm air masses from the north bring warmer temperatures.[53] The lowest temperature ever recorded in central Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires Central Observatory) was −5.4 °C (22 °F) on 9 July 1918.[50] Snow is very rare in the city: the last snowfall occurred on 9 July 2007 when, during the coldest winter in Argentina in almost 30 years, severe snowfalls and blizzards hit the country. It was the first major snowfall in the city in 89 years.[54][55]

Spring and autumn are characterized by changeable weather conditions.[56] Cold air from the south can bring cooler temperatures while hot humid air from the north bring hot temperatures.[46]

The city receives 1,236.3 mm (49 in) of precipitation per year.[47] Because of its geomorphology along with an inadequate drainage network, the city is highly vulnerable to flooding during periods of heavy rainfall.[57][58][59][60]

| Climate data for Buenos Aires Central Observatory, located in Agronomía (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 43.3 (109.9) |

38.7 (101.7) |

37.9 (100.2) |

36.0 (96.8) |

31.6 (88.9) |

28.5 (83.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.4 (93.9) |

35.3 (95.5) |

35.6 (96.1) |

36.8 (98.2) |

40.5 (104.9) |

43.3 (109.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.1 (86.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

16.0 (60.8) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.9 (76.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

21.9 (71.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.8 (55.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.9 (64.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 20.1 (68.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

7.4 (45.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−4 (25) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−4 (25) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−2 (28) |

1.6 (34.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 138.8 (5.46) |

127.1 (5.00) |

140.1 (5.52) |

119.0 (4.69) |

92.3 (3.63) |

58.8 (2.31) |

60.6 (2.39) |

64.2 (2.53) |

72.0 (2.83) |

127.2 (5.01) |

117.3 (4.62) |

118.9 (4.68) |

1,236.3 (48.67) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 9.0 | 8.0 | 8.8 | 9.1 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 99.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64.7 | 69.7 | 72.6 | 76.3 | 77.5 | 78.7 | 77.4 | 73.2 | 70.1 | 69.1 | 66.7 | 63.6 | 71.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 279.0 | 240.8 | 229.0 | 220.0 | 173.6 | 132.0 | 142.6 | 173.6 | 189.0 | 227.0 | 252.0 | 266.6 | 2,525.2 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 12 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 7 |

| Source 1: Servicio Meteorológico Nacional[47][61] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun, 1961–1990),[62][note 1] Weather Atlas (UV)[63] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Buenos Aires Central Observatory (2010-2019) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 36.7 (98.1) |

35.3 (95.5) |

32.5 (90.5) |

29.7 (85.5) |

25.3 (77.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

26.2 (79.2) |

28.5 (83.3) |

29.2 (84.6) |

33.9 (93.0) |

35.9 (96.6) |

37.5 (99.5) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 13.8 (56.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

9.5 (49.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

1.4 (34.5) |

0.5 (32.9) |

2.0 (35.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

0.3 (32.5) |

| Source: Servicio Meteorológico Nacional[64] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Buenos Aires | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 25.0 (77.0) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

18.3 (65.0) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 14.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [63] | |||||||||||||

Government and politics

Government structure

The Executive is held by the Chief of Government (Spanish: Jefe de Gobierno), elected for a four-year term together with a Deputy Chief of Government, who presides over the 60-member Buenos Aires City Legislature. Each member of the Legislature is elected for a four-year term; half of the legislature is renewed every two years. Elections use the D'Hondt method of proportional representation. The Judicial branch is composed of the Supreme Court of Justice (Tribunal Superior de Justicia), the Magistrate's Council (Consejo de la Magistratura), the Public Ministry, and other City Courts. Article 61 of the 1996 Constitution of the City of Buenos Aires states that "Suffrage is free, equal, secret, universal, compulsory and non-accumulative. Resident aliens enjoy this same right, with its corresponding obligations, on equal terms with Argentine citizens registered in the district, under the terms established by law."[65]

Legally, the city has less autonomy than the Provinces. In June 1996, shortly before the City's first Executive elections were held, the Argentine National Congress issued the National Law 24.588 (known as Ley Cafiero, after the Senator who advanced the projemacct) by which the authority over the 25,000-strong Argentine Federal Police and the responsibility over the federal institutions residing at the City (e.g., National Supreme Court of Justice buildings) would not be transferred from the National Government to the Autonomous City Government until a new consensus could be reached at the National Congress. Furthermore, it declared that the Port of Buenos Aires, along with some other places, would remain under constituted federal authorities.[66] As of 2011, the deployment of the Metropolitan Police of Buenos Aires is ongoing.[67]

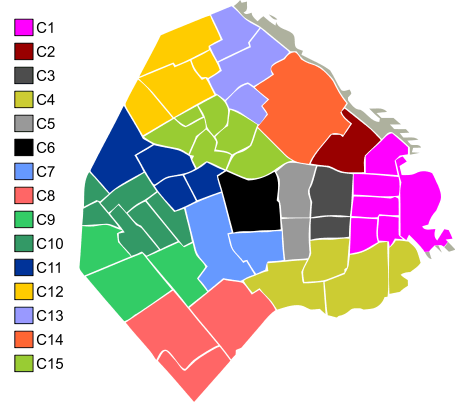

Beginning in 2007, the city has embarked on a new decentralization scheme, creating new Communes (comunas) which are to be managed by elected committees of seven members each. Buenos Aires is represented in the Argentine Senate by three senators (as of 2017, Federico Pinedo, Marta Varela and Pino Solanas).[68] The people of Buenos Aires also elect 25 national deputies to the Argentine Chamber of Deputies.

.jpg) The Buenos Aires City Hall in the right corner of entrance to the Avenida de Mayo

The Buenos Aires City Hall in the right corner of entrance to the Avenida de Mayo

Demographics

The population in 1825 was over 81,000 people.[69]

Census data

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 5,166,140 | — |

| 1960 | 6,761,837 | +30.9% |

| 1970 | 8,416,170 | +24.5% |

| 1980 | 9,919,781 | +17.9% |

| 1990 | 11,147,566 | +12.4% |

| 2000 | 12,503,871 | +12.2% |

| 2010 | 14,245,871 | +13.9% |

| 2019 | 15,057,273 | +5.7% |

| for Buenos Aires Agglomeration:[71] | ||

In the census of 2010 there were 2,891,082 people residing in the city.[73] The population of Greater Buenos Aires was 13,147,638 according to 2010 census data.[74] The population density in Buenos Aires proper was 13,680 inhabitants per square kilometer (34,800 per mi2), but only about 2,400 per km2 (6,100 per mi2) in the suburbs.[75]

The population of Buenos Aires proper has hovered around 3 million since 1947, due to low birth rates and a slow migration to the suburbs. The surrounding districts have, however, expanded over fivefold (to around 10 million) since then.[73]

The 2001 census showed a relatively aged population: with 17% under the age of fifteen and 22% over sixty, the people of Buenos Aires have an age structure similar to those in most European cities. They are older than Argentines as a whole (of whom 28% were under 15, and 14% over 60).[76]

Two-thirds of the city's residents live in apartment buildings and 30% in single-family homes; 4% live in sub-standard housing.[77] Measured in terms of income, the city's poverty rate was 8.4% in 2007 and, including the metro area, 20.6%.[78] Other studies estimate that 4 million people in the metropolitan Buenos Aires area live in poverty.[79]

The city's resident labor force of 1.2 million in 2001 was mostly employed in the services sector, particularly social services (25%), commerce and tourism (20%) and business and financial services (17%); despite the city's role as Argentina's capital, public administration employed only 6%. Manufacturing still employed 10%.[77]

Largest groups of foreign born people :

| Paraguay | 79,295 |

| Bolivia | 75,948 |

| Peru | 59,389 |

| Uruguay | 29,754 |

| Spain | 24,578 |

| Italy | 21,216 |

| Chile | 8,831 |

| Brazil | 7,181 |

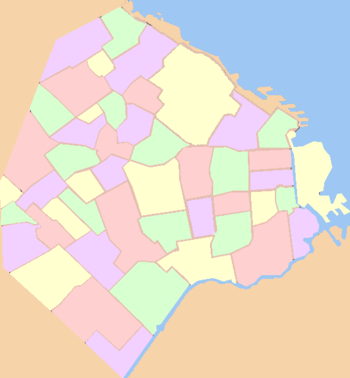

Districts

The city is divided into barrios (neighborhoods) for administrative purposes, a division originally based on Catholic parroquias (parishes).[80] A common expression is that of the Cien barrios porteños ("One hundred porteño neighborhoods"), referring to a composition made popular in the 1940s by tango singer Alberto Castillo; however, Buenos Aires only consists of 48 official barrios. There are several subdivisions of these districts, some with a long history and others that are the product of a real estate invention. A notable example is Palermo – the city's largest district – which has been subdivided into various barrios, including Palermo Soho, Palermo Hollywood, Las Cañitas and Palermo viejo, among others. A newer scheme has divided the city into 15 comunas (communes).[81]

L. P.

Liniers

|

|

Population origin

The majority of porteños have European origins, mostly from the Italian regions of Calabria, Liguria, Piedmont, Lombardy, Sicily and Campania and from the Andalusian, Galician, Asturian, and Basque regions of Spain.[82][83] Unrestricted waves of European immigrants to Argentina starting in the mid-19th century significantly increased the country's population, even causing the number of porteños to triple between 1887 and 1915 from 500,000 to 1.5 million.[84]

Other significant European origins include Slovak, German, Irish, Norwegian, Polish, French, Portuguese, Swedish, Greek, Czech, Albanian, Croatian, Dutch, Russian, Serbian, English, Hungarian and Bulgarian. In the 1980s and 1990s, there was a small wave of immigration from Romania and Ukraine.[85] There is a minority of criollo citizens, dating back to the Spanish colonial days. The Criollo and Spanish-aboriginal (mestizo) population in the city has increased mostly as a result of immigration from the inner provinces and from other countries such as neighboring Bolivia, Paraguay, Chile and Peru, since the second half of the 20th century.

The Jewish community in Greater Buenos Aires numbers around 250,000, and is the largest in the country. The city is also eighth largest in the world in terms of Jewish population.[86] Most are of Northern, Western, Central, and Eastern European Ashkenazi origin, primarily Swedish, Dutch, Polish, German, and Russian Jews, with a significant Sephardic minority, mostly made up of Syrian Jews and Lebanese Jews.[87] Important Lebanese, Georgian, Syrian and Armenian communities have had a significant presence in commerce and civic life since the beginning of the 20th century.

Most East Asian immigration in Buenos Aires comes from China. Chinese immigration is the fourth largest in Argentina, with the vast majority of them living in Buenos Aires and its metropolitan area.[88] In the 1980s, most of them were from Taiwan, but since the 1990s the majority of Chinese immigrants come from the continental province of Fujian.[88] The mainland Chinese who came from Fujian mainly installed supermarkets throughout the city and the suburbs; these supermarkets are so common that, in average, there is one every two and a half blocks and are simply referred to as el chino ("the Chinese").[88][89] Japanese immigrants are mostly from the Okinawa Prefecture. They started the dry cleaning business in Argentina, an activity that is considered idiosyncratic to the Japanese immigrants in Buenos Aires.[90] Korean Immigration occurred after the division of Korea; they mainly settled in Flores and Once.[91]

In the 2010 census [INDEC], 2.1% of the population or 61,876 persons declared to be Amerindian or first-generation descendants of Amerindians in Buenos Aires (not including the 24 adjacent Partidos that make up Greater Buenos Aires).[92] Amongst the 61,876 persons who are of indigenous origin, 15.9% are Quechua people, 15.9% are Guaraní, 15.5% are Aymara and 11% are Mapuche.[92] Within the 24 adjacent Partidos, 186,640 persons or 1.9% of the total population declared themselves to be Amerindian.[92] Amongst the 186,640 persons who are of indigenous origin, 21.2% are Guaraní, 19% are Toba, 11.3% are Mapuche, 10.5% are Quechua and 7.6% are Diaguita.[92]

In the city, 15,764 people identified themselves as Afro-Argentine in the 2010 Census.[93]

Religion

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Buenos Aires was the second largest Catholic city in the world after Paris.[94][95] Christianity is still the most prevalently practiced religion in Buenos Aires (~71.4%),[96] a 2019 CONICET survey on religious beliefs and attitudes found that the inhabitants of the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area (Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires, AMBA) were 56.4% Catholic, 26.2% non-religious and 15% Evangelical; making it the region of the country with the highest proportion of irreligious people.[96] A previous CONICET survey from 2008 had found that 69.1% were Catholic, 18% "indifferent", 9.1% Evangelical, 1.4% Jehovah's Witnesses or Mormons and 2.3% adherents to other religions.[97] The comparison between both surveys reveals that the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area is the region in which the decline of Catholicism was most pronounced during the last decade.[96]

Buenos Aires is also home to the largest Jewish community in Latin America and the second largest in the Western Hemisphere after the United States.[98][99] The Jewish community of Buenos Aires has historically been characterized by its high level of assimilation, organization and influence in the cultural history of the city.[100]

Buenos Aires is the seat of a Roman Catholic metropolitan archbishop (the Catholic primate of Argentina), currently Archbishop Mario Poli. His predecessor, Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, was elected to the Papacy as Pope Francis on 13 March 2013. There are Protestant, Orthodox Christian, Muslim and Buddhist minorities. The city is home to the largest mosque in South America.[101]

.jpg) The Metropolitan Cathedral is the main Catholic church in the city.

The Metropolitan Cathedral is the main Catholic church in the city.- King Fahd Islamic Cultural Centre is the largest mosque in Latin America.

- Templo Libertad is a Jewish house of prayer. Argentina's Jewish population is the largest in Latin America.

- Anglican Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, is the oldest non-Catholic church building in Latin America.

- Russian Orthodox church in San Telmo.

Urban problems

Villas miserias range from small groups of precarious houses to larger, more organised communities with thousands of residents.[102] In rural areas, the houses in the villas miserias might be made of mud and wood. Villas miseria are found around and inside the large cities of Buenos Aires, Rosario, Córdoba and Mendoza, among others

Buenos Aires has below 2 m2 (22 sq ft) of green space per person, which is 90% less than New York, 85% less than Madrid and 80% less than Paris. The World Health Organization (WHO), in its concern for public health, produced a document stating that every city should have a minimum of 9 m2 (97 sq ft) of green space per person. An optimal amount would sit between 10 and 15 m2 (161 sq ft) per person.[103][104]

Economy

.jpg)

Buenos Aires is the financial, industrial, and commercial hub of Argentina. The economy in the city proper alone, measured by Gross Geographic Product (adjusted for purchasing power), totaled US$84.7 billion (US$34,200 per capita) in 2011[105] and amounts to nearly a quarter of Argentina's as a whole.[106] Metro Buenos Aires, according to one well-quoted study, constitutes the 13th largest economy among the world's cities.[107] The Buenos Aires Human Development Index (0.923 in 1998) is likewise high by international standards.[108]

Port

The port of Buenos Aires is one of the busiest in South America; navigable rivers by way of the Rio de la Plata connect the port to north-east Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay. As a result, it serves as the distribution hub for a vast area of the south-eastern region of the continent. The Port of Buenos Aires handles over 11 million revenue tons annually,[109] and Dock Sud, just south of the city proper, handles another 17 million metric tons.[110] Tax collection related to the port has caused many political problems in the past, including a conflict in 2008 that led to protests and a strike in the agricultural sector after the government raised export tariffs.[111]

_Buenos_Aires%2C_Argentina.jpg)

Services

The city's services sector is diversified and well-developed by international standards, and accounts for 76% of its economy (compared to 59% for all of Argentina's).[112] Advertising, in particular, plays a prominent role in the export of services at home and abroad. The financial and real-estate services sector is the largest, however, and contributes to 31% of the city's economy. Finance (about a third of this) in Buenos Aires is especially important to Argentina's banking system, accounting for nearly half the nation's bank deposits and lending.[112] Nearly 300 hotels and another 300 hostels and bed & breakfasts are licensed for tourism, and nearly half the rooms available were in four-star establishments or higher.[113]

Manufacturing

Manufacturing is, nevertheless, still prominent in the city's economy (16%) and, concentrated mainly in the southern part of the city. It benefits as much from high local purchasing power and a large local supply of skilled labor as it does from its relationship to massive agriculture and industry just outside the city limits. Construction activity in Buenos Aires has historically been among the most accurate indicators of national economic fortunes, and since 2006 around 3 million square metres (32 million square feet) of construction has been authorized annually.[112] Meat, dairy, grain, tobacco, wool and leather products are processed or manufactured in the Buenos Aires metro area. Other leading industries are automobile manufacturing, oil refining, metalworking, machine building and the production of textiles, chemicals, clothing and beverages.

Government finances

The city's budget, per Mayor Macri's 2011 proposal, included US$6 billion in revenues and US$6.3 billion in expenditures. The city relies on local income and capital gains taxes for 61% of its revenues, while federal revenue sharing contributes 11%, property taxes, 9%, and vehicle taxes, 6%. Other revenues include user fees, fines and gambling duties. The city devotes 26% of its budget to education, 22% for health, 17% for public services and infrastructure, 16% for social welfare and culture, 12% in administrative costs and 4% for law enforcement. Buenos Aires maintains low debt levels and its service requires less than 3% of the budget.[114]

Culture

.jpg)

Strongly influenced by European culture, Buenos Aires is sometimes referred to as the "Paris of South America".[2][115] The city has the busiest live theatre industry in Latin America, with scores of theaters and productions.[116] In fact, every weekend, there are about 300 active theatres with plays, a number that places the city as 1st worldwide, more than either London, New York or Paris, cultural Meccas in themselves. The number of cultural festivals with more than 10 sites and 5 years of existence also places the city as 2nd worldwide, after Edinburgh.[117] The Kirchner Cultural Centre located in Buenos Aires, is the largest of Latin America,[118][119] and the third worldwide.[120]

Buenos Aires is the home of the Teatro Colón, an internationally rated opera house.[121] There are several symphony orchestras and choral societies. The city has numerous museums related to history, fine arts, modern arts, decorative arts, popular arts, sacred art, arts and crafts, theatre and popular music, as well as the preserved homes of noted art collectors, writers, composers and artists. The city is home to hundreds of bookstores, public libraries and cultural associations (it is sometimes called "the city of books"), as well as the largest concentration of active theatres in Latin America. It has a zoo and botanical garden, a large number of landscaped parks and squares, as well as churches and places of worship of many denominations, many of which are architecturally noteworthy.[121]

The city has been a member of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network after it was named "City of Design" in 2005.[122]

Porteño identity

The identity of porteños has a rich and complex history, and has been the subject of much analysis and scrutiny.[123] The great European immigration wave of the early 20th century was integral to "the growing primacy of Buenos Aires and the accompanying urban identity", and established the division between urban and rural Argentina more deeply.[124] Immigrants "brought new traditions and cultural markers to the city," which were "then reimagined in the porteño context, with new layers of meanings because of the new location."[125] The heads of state's attempt to populate the country and reframe the national identity resulted in the concentration of immigrants in the city and its suburbs, who generated a culture that is a "product of their conflicts of integration, their difficulties to live and their communication puzzles."[126] In response to the immigration wave, during the 1920s and 1930s a nationalist trend within the Argentine intellectual elite glorified the gaucho figure as an exemplary archetype of Argentine culture; its synthesis with the European traditions conformed the new urban identity of Buenos Aires.[127] The complexity of Buenos Aires' integration and identity formation issues increased when immigrants realized that their European culture could help them gain a greater social status.[128] As the rural population moved to the industrialized city from the 1930s onwards, they reaffirmed their European roots,[129] adopting endogamy and founding private schools, newspapers in foreign languages, and associations that promoted adherence to their countries of origin.[128]

Porteños are generally characterized as night owls, cultured, talkative, uninhibited, sensitive, nostalgic, observative and arrogant.[16][123] Argentines outside Buenos Aires often stereotype its inhabitants as egotist people, a feature that people from the Americas and westerners in general commonly attribute to the entire Argentine population and use as the subject of numerous jokes.[130] Writing for BBC Mundo Cristina Pérez felt that "the idea of the [Argentines'] vastly developed ego finds strong evidence in lunfardo dictionaries," in words such as "engrupido" (meaning "vain" or "conceited") and "compadrito" (meaning both "brave" and "braggart"), the latter being an archetypal figure of tango.[131] Paradoxically, porteños are also described as highly self-critical, something that has been called "the other side of the ego coin."[131] Writers consider that these behaviours are the consequence of the European immigration and prosperity the city experienced during the early 20th century, which generated a feeling of superiority in parts of the population.[130]

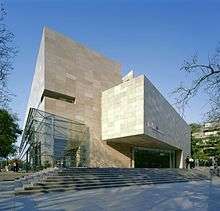

Art

Buenos Aires has a thriving arts culture,[132] with "a huge inventory of museums, ranging from obscure to world-class."[133] The barrios of Palermo and Recoleta are the city's traditional bastions in the diffusion of art, although in recent years there has been a tendency of appearance of exhibition venues in other districts such as Puerto Madero or La Boca; renowned venues include MALBA, the National Museum of Fine Arts, Fundación Proa, Faena Arts Center, and the Usina del Arte.[134] Other popular institutions are the Buenos Aires Museum of Modern Art, the Quinquela Martín Museum, the Evita Museum, the Fernández Blanco Museum, the José Hernández Museum, and the Palais de Glace, among others.[135] A traditional event that occurs once a year is La Noche de los Museos ("Night of the Museums"), when the city's museums, universities, and artistic spaces open their doors for free until early morning; it usually takes place in November.[136][137]

The first major artistic movements in Argentina coincided with the first signs of political liberty in the country, such as the 1913 sanction of the secret ballot and universal male suffrage, the first president to be popularly elected (1916), and the cultural revolution that involved the University Reform of 1918. In this context, in which there continued to be influence from the Paris School (Modigliani, Chagall, Soutine, Klee), three main groups arose. Buenos Aires has been the birthplace of several artists and movements of national and international relevance, and has become a central motif in Argentine artistic production, specially since the 20th century.[138] Examples include: the Paris Group – so named for being influenced by the School of Paris – constituted by Antonio Berni, Aquiles Badi, Lino Enea Spilimbergo, Raquel Forner and Alfredo Bigatti, among others; and[139] the La Boca artists – including Benito Quinquela Martín and Alfredo Lazzari, among others – who mostly came from Italy or were of Italian descent, and usually painted scenes from this working-class port neighbourhood.[140] During the 1960s, the Torcuato di Tella Institute – located in Florida Street – became a leading local center for pop art, performance art, installation art, experimental theatre, and conceptual art; this generation of artists included Marta Minujín, Dalila Puzzovio, David Lamelas and Clorindo Testa.

Buenos Aires has also become a prominent center of contemporary street art; its welcoming attitude has made it one of the world's top capitals of such expression.[141][142] The city's turbulent modern political history has "bred an intense sense of expression in porteños," and urban art has been used to depict these stories and as a means of protest.[132][142] However, not all of its street art concerns politics, it is also used as a symbol of democracy and freedom of expression.[132] Murals and graffiti are so common that they are considered "an everyday occurrence," and have become part of the urban landscape of barrios such as Palermo, Villa Urquiza, Coghlan and San Telmo.[143] This has to do with the legality of such activities —provided that the building owner has consented—, and the receptiveness of local authorities, who even subsidize various works.[141] The abundance of places for urban artists to create their work, and the relatively lax rules for street art, have attracted international artists such as Blu, Jef Aérosol, Aryz, ROA, and Ron English.[141] Guided tours to see murals and graffiti around the city have been growing steadily.[144]

Literature

.jpg)

Buenos Aires has long been considered an intellectual and literary capital of Latin America and the Spanish-speaking world.[145][146] Despite its short urban history, Buenos Aires has an abundant literary production; its mythical-literary network "has grown at the same rate at which the streets of the city earned its shores to the pampas and buildings stretched its shadow on the curb."[147] During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, culture boomed along with the economy and the city emerged as a literary capital and the seat of South America's most powerful publishing industry,[148] and "even if the economic path grew rocky, ordinary Argentines embraced and stuck to the habit of reading."[149] By the 1930s, Buenos Aires was the undisputed literary capital of the Spanish-speaking world, with Victoria Ocampo founding the highly influential Sur magazine—which dominated Spanish-language literature for thirty years—[150] and the arrival of prominent Spanish writers and editors who were escaping the civil war.[149]

Buenos Aires is one of the most prolific book publishers in Latin America and has more bookstores per capita than any other major city in the world.[149][151] Buenos Aires has at least 734 bookstores—roughly 25 bookshops for every 100,000 inhabitants—far above other world cities like London, Paris, Madrid, Moscow and New York.[149][151] The city also has a thriving market for secondhand books, ranking third in terms of secondhand bookshops per inhabitant, most of them congregated along Avenida Corrientes.[151] Buenos Aires' book market has been described as "catholic in taste, immune to fads or fashion", with "wide and varied demand."[151] The popularity of reading among porteños has been variously linked to the wave of mass immigration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and to the city's "obsession" with psychoanalysis.[151]

The Buenos Aires International Book Fair has been a major event in the city since the first fair in 1975,[145] having been described as "perhaps the most important and largest annual literary event in the Spanish-speaking world,"[152] and "the most important cultural event in Latin America".[153] In its 2019 edition, the Book Fair was attended by 1.8 million people.[153]

Language

Known as Rioplatense Spanish, Buenos Aires' Spanish (as that of other cities like Rosario and Montevideo, Uruguay) is characterised by voseo, yeísmo and aspiration of s in various contexts. It is heavily influenced by the dialects of Spanish spoken in Andalusia and Murcia.

In the early 20th century, Argentina absorbed millions of immigrants, many of them Italians, who spoke mostly in their local dialects (mainly Neapolitan, Sicilian and Genoese). Their adoption of Spanish was gradual, creating a pidgin of Italian dialects and Spanish that was called cocoliche. Its usage declined around the 1950s. A phonetic study conducted by the Laboratory for Sensory Investigations of CONICET and the University of Toronto showed that the prosody of porteño is closer to the Neapolitan language of Italy than to any other spoken language.[154]

Many Spanish immigrants were from Galicia, and Spaniards are still generically referred to in Argentina as gallegos (Galicians). Galician language, cuisine and culture had a major presence in the city for most of the 20th century. In recent years, descendants of Galician immigrants have led a mini-boom in Celtic music (which also highlighted the Welsh traditions of Patagonia).

Yiddish was commonly heard in Buenos Aires, especially in the Balvanera garment district and in Villa Crespo until the 1960s. Most of the newer immigrants learn Spanish quickly and assimilate into city life.

The Lunfardo argot originated within the prison population, and in time spread to all porteños. Lunfardo uses words from Italian dialects, from Brazilian Portuguese, from African and Caribbean languages and even from English. Lunfardo employs humorous tricks such as inverting the syllables within a word (vesre). Today, Lunfardo is mostly heard in tango lyrics;[155] the slang of the younger generations has been evolving away from it.

Buenos Aires was also the first city to host a Mundo Lingo event on 7 July 2011, which have been after replicated in up to 15 cities in 13 countries.[156]

Music

According to the Harvard Dictionary of Music, "Argentina has one of the richest art music traditions and perhaps the most active contemporary musical life" in South America.[157] Buenos Aires boasts of several professional orchestras, including the Argentine National Symphony Orchestra, the Ensamble Musical de Buenos Aires and the Camerata Bariloche; as well as various conservatories that offer professional music education, like the Conservatorio Nacional Superior de Música.[157] As a result of the growth and commercial prosperity of the city in the late 18th century, the theatre became a vital force in Argentine musical life, offering Italian and French operas and Spanish zarzuelas.[157] Italian music was very influential during the 19th century and the early 20th century, in part because of immigration, but operas and salon music were also composed by Argentines, including Francisco Hargreaves and Juan Gutiérrez.[157] A nationalist trend that drew from Argentine traditions, literature and folk music was an important force during the 19th century, including composers Alberto Williams, Julián Aguirre, Arturo Berutti and Felipe Boero.[157] In the 1930s, composers such as Juan Carlos Paz and Alberto Ginastera "began to espouse a cosmopolitan and modernist style, influenced by twelve-tone techniques and serialism"; while avant-garde music thrived by the 1960s, with the Rockefeller Foundation financing the Centro Interamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales, which brought internationally famous composers to work and teach in Buenos Aires, also establishing an electronic music studio.[157]

The Río de la Plata is known for being the birthplace of tango, which is considered an emblem of Buenos Aires.[158] The city considers itself the Tango World Capital, and as such hosts many related events, the most important being an annual festival and world tournament.[158] The most important exponent of the genre is Carlos Gardel, followed by Aníbal Troilo; other important composers include Alfredo Gobbi, Ástor Piazzolla, Osvaldo Pugliese, Mariano Mores, Juan D'Arienzo and Juan Carlos Cobián.[159] Tango music experienced a period of splendor during the 1940s, while in the 1960s and 1970s nuevo tango appeared, incorporating elements of classical and jazz music. A contemporary trend is neotango (also known as electrotango), with exponents such as Bajofondo and Gotan Project. On 30 September 2009, UNESCO's Intergovernmental Committee of Intangible Heritage declared tango part of the world's cultural heritage, making Argentina eligible to receive financial assistance in safeguarding tango for future generations.[160]

The city hosts several music festivals every year. A popular genre is electronic dance music, with festivals including Creamfields BA, SAMC, Moonpark, and a local edition of Ultra Music Festival. Other well-known events include the Buenos Aires Jazz Festival, Personal Fest, Quilmes Rock and Pepsi Music. Some music festivals are held in Greater Buenos Aires, like Lollapalooza, which takes place at the Hipódromo de San Isidro in San Isidro.

Cinema

Argentine cinema history began in Buenos Aires with the first film exhibition on 18 July 1896 at the Teatro Odeón.[161][162] With his 1897 film, La bandera Argentina, Eugène Py became one of the first filmmakers of the country; the film features a waving Argentine flag located at Plaza de Mayo.[162] In the early 20th century, the first cinema theatres of the country opened in Buenos Aires, and newsreels appeared, most notably El Viaje de Campos Salles a Buenos Aires.[162] The real industry emerged with the advent of sound films, the first one being Muñequitas porteñas (1931).[161][162] The newly founded Argentina Sono Film released ¡Tango! in 1933, the first integral sound production in the country.[162] During the 1930s and the 1940s (commonly referred as the "Golden Age" of Argentine cinema), many films revolved around the city of Buenos Aires and tango culture, reflected in titles such as La vida es un tango, El alma del bandoneón, Adiós Buenos Aires, El Cantor de Buenos Aires and Buenos Aires canta. Argentine films were exported across Latin America, specially Libertad Lamarque's melodramas, and the comedies of Luis Sandrini and Niní Marshall. The popularity of local cinema in the Spanish-speaking world played a key role in the massification of tango music. Carlos Gardel, an iconic figure of tango and Buenos Aires, became an international star by starring in several films during that era.

In response to large studio productions, the "Generation of the 60s" appeared, a group of filmmakers that produced the first modernist films in Argentina during that early years of that decade. These included Manuel Antín, Lautaro Murúa and René Mugica, among others.[163] During the second half of the decade, films of social protest were presented in clandestine exhibitions, the work of Grupo Cine Liberación and Grupo Cine de la Base, who advocated what they called "Third Cinema". At that time, the country was under a military dictatorship after the coup d'état known as Argentine Revolution. One of the most notable films of these movement is La hora de los hornos (1968) by Fernando Solanas. During the period of democracy between 1973 and 1975, the local cinema experienced critical and commercial success, with titles including Juan Moreira (1973), La Patagonia rebelde (1974), La Raulito (1975), and La tregua (1974) – which became the first Argentine film nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. However, because of censorship and a new military government, Argentine cinema stalled until the return of democracy in the 1980s. This generation – known as "Argentine Cinema in Liberty and Democracy" – were mostly young or postponed filmmakers, and gained international notoriety. Camila (1984) by María Luisa Bemberg was nominated for the Best Foreign Film at the Academy Awards, and Luis Puenzo's La historia oficial (1985) was the first Argentine film to receive the award.

Located in Buenos Aires is the Pablo Ducrós Hicken Museum of Cinema, the only one in the country dedicated to Argentine cinema and a pioneer of its kind in Latin America.[164] Every year, the city hosts the Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema (BAFICI), which, in its 2015 edition, featured 412 films from 37 countries, and an attendance of 380 thousand people.[165] Buenos Aires also hosts various other festivals and film cycles, like the Buenos Aires Rojo Sangre, devoted to horror.

Media

Buenos Aires is home to five Argentine television networks: America, Television Pública Argentina, El Nueve, Telefe, and El Trece. Four of them are located in Buenos Aires, and the studios of America is located in La Plata.

Fashion

Buenos Aires' inhabitants have been historically characterized as "fashion-conscious".[166][167][168] National designers display their collections annually at the Buenos Aires Fashion Week (BAFWEEK) and related events.[169] Inevitably being a season behind, it fails to receive much international attention.[170] Nevertheless, the city remains an important regional fashion capital. According to Global Language Monitor, as of 2017 the city is the 20th leading fashion capital in the world, ranking second in Latin America after Rio de Janeiro.[171] In 2005, Buenos Aires was appointed as the first UNESCO City of Design,[172] and received this title once again in 2007.[173] Since 2015, the Buenos Aires International Fashion Film Festival Buenos Aires (BAIFFF) takes place, sponsored by the city and Mercedes-Benz.[174] The government of the city also organizes La Ciudad de Moda ("The City of Fashion"), an annual event that serves as a platform for emerging creators and attempts to boost the sector by providing management tools.[175]

The neighbourhood of Palermo, particularly the area known as Soho, is where the latest fashion and design trends are presented.[176] The "sub-barrio" of Palermo Viejo is also a popular port of call for fashion in the city.[177] An increasing number of young, independent designers are also setting up their own shops in the bohemian neighbourhood of San Telmo, known for its wide variety of markets and antique shops.[176] Recoleta, on the other hand, is the quintessential neighbourhood for exclusive and upscale fashion houses.[176] In particular, Avenida Alvear is home to the most exclusive representatives of haute couture in the city.[177]

Cityscape

Architecture

Buenos Aires architecture is characterized by its eclectic nature, with elements resembling Paris and Madrid. There is a mix, due to immigration, of Colonial, Art Deco, Art Nouveau, Neo-Gothic, and French Bourbon styles.[178] Italian and French influences increased after the declaration of independence at the beginning of the 19th century, though the academic style persisted until the first decades of the 20th century.

Attempts at renovation took place during the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, when European influences penetrated into the country, reflected by several buildings of Buenos Aires such as the Iglesia Santa Felicitas by Ernesto Bunge; the Palace of Justice, the National Congress, all of them by Vittorio Meano, and the Teatro Colón, by Francesco Tamburini and Vittorio Meano.

The simplicity of the Rioplatense baroque style can be clearly seen in Buenos Aires through the works of Italian architects such as André Blanqui and Antonio Masella, in the churches of San Ignacio, Nuestra Señora del Pilar, the Cathedral and the Cabildo.

In 1912, the Basilica del Santisimo Sacramento was opened to the public. Totally built by the generous donation of Mercedes Castellanos de Anchorena, a member of Argentina's most prominent family, the church is an excellent example of French neo-classicism. With extremely high-grade decorations in its interior, the magnificent Mutin-Cavaillé coll organ (the biggest ever installed in an Argentine church with more than four-thousand tubes and four manuals) presided the nave. The altar is full of marble, and was the biggest ever built in South America at that time.[179]

In 1919, the construction of Palacio Barolo began. This was South America's tallest building at the time, and was the first Argentine skyscraper built with concrete (1919–1923).[180] The building was equipped with 9 elevators, plus a 20-metre high lobby hall with paintings in the ceiling and Latin phrases embossed in golden bronze letters. A 300,000-candela beacon was installed at the top (110 m), making the building visible even from Uruguay. In 2009, the Barolo Palace went under an exhaustive restoration, and the beacon was made operational again.

In 1936, the Kavanagh building was inaugurated, with 120 metres (390 feet) height, 12 elevators (provided by Otis) and the world's first central air-conditioning system (provided by north-American company "Carrier"), is still an architectural landmark in Buenos Aires.[181]

The architecture of the second half of the 20th century continued to reproduce French neoclassic models, such as the headquarters of the Banco de la Nación Argentina built by Alejandro Bustillo, and the Museo Hispanoamericano de Buenos Aires of Martín Noel. However, since the 1930s, the influence of Le Corbusier and European rationalism consolidated in a group of young architects from the University of Tucumán, among whom Amancio Williams stands out. The construction of skyscrapers proliferated in Buenos Aires until the 1950s. Newer modern high-technology buildings by Argentine architects in the last years of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st include the Le Parc Tower by Mario Álvarez, the Torre Fortabat by Sánchez Elía and the Repsol-YPF tower by César Pelli.

Education

Primary education

Primary education comprise grades 1–7. Most primary schools in the city still adhere to the traditional seven-year primary school, but kids can do grades 1–6 if their high schools lasts 6 years, such as ORT Argentina.

Secondary education

Secondary education in Argentina is called Polimodal ("polymodal", that is, having multiple modes), since it allows the student to choose their orientation. Polimodal is usually 3 years of schooling, although some schools have a fourth year. Before entering the first year of polimodal, students choose an orientation, among these five: Humanities and Social Sciences, Economics and Management of Organizations, Art and Design, Health and Sport and Biology and Natural Sciences.

Nevertheless, in Buenos Aires, secondary education consists of 5 years, called from 1st year to 5th year, as opposed to primary education's 1st to 7th grade. Most schools do not require students to choose their orientation, as they study the basic such as maths, biology, art, history and technology, but there are schools that do, whether they are orientated to a certain profession or they have orientations to choose from when they reach a specific year.

Some high schools depend on the University of Buenos Aires, and these require an admission course when students are taking the last year of high school. These high schools are ILSE, CNBA, Escuela Superior de Comercio Carlos Pellegrini and Escuela de Educación Técnica Profesional en Producción Agropecuaria y Agroalimentaria (School of Professional Technique Education in Agricultural and Agri-food Production). The last two do have a specific orientation.

In December 2006 the Chamber of Deputies of the Argentine Congress passed a new National Education Law restoring the old system of primary followed by secondary education, making secondary education obligatory and a right, and increasing the length of compulsory education to 13 years. The government vowed to put the law in effect gradually, starting in 2007.[182]

University education

There are many public universities in Argentina, as well as a number of private universities. The University of Buenos Aires, one of the top learning institutions in South America, has produced five Nobel Prize winners and provides taxpayer-funded education for students from all around the globe.[183][184][185] Buenos Aires is a major center for psychoanalysis, particularly the Lacanian school. Buenos Aires is home to several private universities of different quality, such as: Universidad Argentina de la Empresa, Buenos Aires Institute of Technology, CEMA University, Favaloro University, Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina, University of Belgrano, University of Palermo, University of Salvador, Universidad Abierta Interamericana, Universidad Argentina John F. Kennedy, Universidad de Ciencias Empresariales y Sociales, Universidad del Museo Social Argentino, Universidad Austral, Universidad CAECE and Torcuato di Tella University.

Tourism

According to the World Travel & Tourism Council,[187] tourism has been growing in the Argentine capital since 2002. In a survey by the travel and tourism publication Travel + Leisure Magazine in 2008, visitors voted Buenos Aires the second most desirable city to visit after Florence, Italy.[188] In 2008, an estimated 2.5 million visitors visited the city.[189]

Visitors have many options such as going to a tango show, an estancia in the Province of Buenos Aires, or enjoying the traditional asado. New tourist circuits have recently evolved, devoted to Argentines such as Carlos Gardel, Eva Perón or Jorge Luis Borges. Before 2011, due to the favourable exchange rate, its shopping centres such as Alto Palermo, Paseo Alcorta, Patio Bullrich, Abasto de Buenos Aires and Galerías Pacífico were frequently visited by tourists. The exchange rate today has hampered tourism and shopping in particular. Notable consumer brands such as Burberry and Louis Vuitton have abandoned the country due to the exchange rate and import restrictions. The city also plays host to musical festivals, some of the largest of which are Quilmes Rock, Creamfields BA, Ultra Music Festival (Buenos Aires) and the Buenos Aires Jazz Festival.

The most popular tourist sites are found in the historic core of the city, in the Montserrat and San Telmo neighborhoods. Buenos Aires was conceived around the Plaza de Mayo, the colony's administrative center. To the east of the square is the Casa Rosada, the official seat of the executive branch of the government of Argentina. To the north, the Catedral Metropolitana which has stood in the same location since colonial times, and the Banco de la Nación Argentina building, a parcel of land originally owned by Juan de Garay. Other important colonial institutions were Cabildo, to the west, which was renovated during the construction of Avenida de Mayo and Julio A. Roca. To the south is the Congreso de la Nación (National Congress), which currently houses the Academia Nacional de la Historia (National Academy of History). Lastly, to the northwest, is City Hall.

Parks

Buenos Aires has over 250 parks and green spaces, the largest concentration of which are on the city's eastern side in the Puerto Madero, Recoleta, Palermo and Belgrano neighbourhoods. Some of the most important are:

- Parque Tres de Febrero, designed by urbanist Jordán Czeslaw Wysocki and architect Julio Dormal, the park was inaugurated on 11 November 1875. The dramatic economic growth of Buenos Aires afterwards helped to lead to its transfer to the municipal domain in 1888, whereby French Argentine urbanist Carlos Thays was commissioned to expand and further beautify the park, between 1892 and 1912. Thays designed the Zoological Gardens, the Botanical Gardens, the adjoining Plaza Italia and the Rose Garden.

- Botanical Gardens, designed by French architect and landscape designer Carlos Thays, the garden was inaugurated on 7 September 1898. Thays and his family lived in an English style mansion, located within the gardens, between 1892 and 1898, when he served as director of parks and walks in the city. The mansion, built in 1881, is currently the main building of the complex.

- Buenos Aires Japanese Gardens Is the largest of its type in the World, outside Japan. Completed in 1967, the gardens were inaugurated on occasion of a State visit to Argentina by Crown Prince Akihito and Princess Michiko of Japan.

- Plaza de Mayo Since being the scene of 25 May 1810 revolution that led to independence, the plaza has been a hub of political life in Argentina.

- Plaza San Martín is a park located in the Retiro neighbourhood of the city. Situated at the northern end of pedestrianized Florida Street, the park is bounded by Libertador Ave. (N), Maipú St. (W), Santa Fe Avenue (S), and Leandro Alem Av. (E).

Theatre

Buenos Aires has over 280 theatres, more than any other city in the world.[190] Because of this, Buenos Aires is declared "World's capital of theater".[191] The city's theatres show everything from musicals to ballet, comedy to circuses.[192] Some of them are:

- Teatro Colón is ranked the third best opera house in the world by National Geographic,[193] and is acoustically considered to be amongst the five best concert venues in the world. The theatre is bounded by the wide 9 de Julio Avenue (technically Cerrito Street), Libertad Street (the main entrance), Arturo Toscanini Street, and Tucumán Street.[194] It is in the heart of the city on a site once occupied by Ferrocarril Oeste's Plaza Parque station.

- Cervantes Theatre, located on Córdoba Avenue and two blocks north of Buenos Aires' renowned opera house, the Colón Theatre, the Cervantes houses three performance halls. The María Guerrero Salon is the theatre's main hall. Its 456 m2 (4,900 ft2) stage features a 12 m (39 ft) rotating circular platform and can be extended by a further 2.7 m (9 ft). The Guerrero Salon can seat 860 spectators, including 512 in the galleries. A secondary hall, the Orestes Caviglia Salon, can seat 150 and is mostly reserved for chamber music concerts. The Luisa Vehíl Salon is a multipurpose room known for its extensive gold leaf decor.

- Teatro Gran Rex is an Art Deco style theatre which opened on 8 July 1937, as the largest cinema in South America.

- Avenida Theatre was inaugurated on Buenos Aires' central Avenida de Mayo in 1908 with a production of Spanish dramatist Lope de Vega's Justice Without Revenge. The production was directed by María Guerrero, a Spanish Argentine theatre director who popularized classical drama in Argentina during the late 19th century and would establish the important Cervantes Theatre in 1921.

Gay tourism

Buenos Aires has become a recipient of LGBT tourism,[195][196] due to the existence of some gay-friendly sites and the legalising of same-sex marriage on 15 July 2010, making it the first country in Latin America, the second in the Americas, and the tenth in the world to do so. Its Gender Identity Law, passed in 2012, made Argentina the "only country that allows people to change their gender identities without facing barriers such as hormone therapy, surgery or psychiatric diagnosis that labels them as having an abnormality". In 2015, the World Health Organization cited Argentina as an exemplary country for providing transgender rights. Despite these legal advances, however, homophobia continues to be a hotly contested social issue in the city and the country.[197]

Hotels

Buenos Aires has various types of accommodation, from luxurious five star to budget located in neighborhoods that are further from the city centre, although the transportation system allows easy and inexpensive access to the city.

There were, as of February 2008, 23 five-star, 61 four-star, 59 three-star and 87 two or one-star hotels, as well as 25 boutique hotels and 39 apart-hotels; another 298 hostels, bed & breakfasts, vacation rentals and other non-hotel establishments were registered in the city. In all, nearly 27,000 rooms were available for tourism in Buenos Aires, of which about 12,000 belonged to four-star, five-star, or boutique hotels. Establishments of a higher category typically enjoy the city's highest occupation rates.[198] The majority of the hotels are located in the central part of the city, in close proximity to most main tourist attractions.

Landmarks

- Cabildo was used as the government house during the colonial times of the Viceroyalty of the River Plate. The original building was finished in 1610 but was soon found to be too small and had to be expanded. Over the years many changes have been made. In 1940, the architect Mario Buschiazzo reconstructed the colonial features of the Cabildo using various original documents.

- Kavanagh building is located at 1065 Florida St. in the barrio of Retiro, overlooking Plaza San Martín. It was constructed in the 1930s in the Rationalist style, by the architects Gregorio Sánchez, Ernesto Lagos and Luis María de la Torre and was finished in 1936. The building is characterised by the austerity of its lines, the lack of external ornamentation and its large prismatic volumes. It was declared a national historical monument in 1999,[199] and is one of the most impressive architectural masterpieces of Buenos Aires. Standing at a height of 120 m, it still retains its impact against the modern skyline of the city. In 1939 its façade received an award from the American Institute of Architects.[200]

- Metropolitan Cathedral is the main Catholic church in Buenos Aires. It is located in the city centre, overlooking Plaza de Mayo, on the corner of San Martín and Rivadavia streets, in the San Nicolás neighbourhood. It is the mother church of the Archdiocese of Buenos Aires.

- National Library is the largest library in Argentina and one of the most important in the Americas.

- The Obelisk was built in May 1936 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the first founding of the city. It is located in the center of the Plaza de la República (Republic Square), the spot where the Argentine flag was flown for the first time in Buenos Aires, at the intersection of Nueve de Julio and Corrientes avenues. Its total height is 67 meters (220 feet) and its base area is 49 square meters (530 square feet). It was designed by architect Alberto Prebisch, and its construction took barely four weeks.

- The Water Company Palace (perhaps the world's most ornate water pumping station)

Las Nereidas font by Lola Mora

Las Nereidas font by Lola Mora

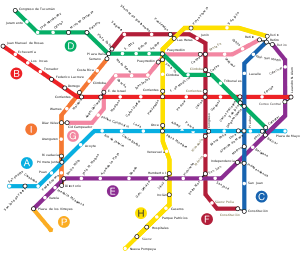

Transport

Airports

The Ministro Pistarini International Airport, commonly known as Ezeiza Airport, is located in the suburb of Ezeiza approximately 22 km south of the city. This airport handles most international air traffic to and from Argentina as well as some domestic flights.