University College London

University College London, officially known as UCL since 2005,[7][8][9] is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom. It is a member institution of the federal University of London, and is the largest university in the United Kingdom by total enrolment apart from the Open University,[5] and the largest by postgraduate enrolment.

Logo since 2005 | ||||||||||||

| Latin: Collegium Universitatis Londinensis[1] | ||||||||||||

Former names | London University (1826–1836) University College, London (1836–1907) University of London, University College (1907–1976) University College London (1977–2005; remains legal name) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motto | Latin: Cuncti adsint meritaeque expectent praemia palmae | |||||||||||

Motto in English | Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward | |||||||||||

| Type | Public research university | |||||||||||

| Established | 1826 | |||||||||||

| Endowment | £118.0 million (at 31 July 2018)[2] | |||||||||||

| Budget | £1.431.7 billion (university); £1.451.1 billion (consolidated) (2017–18)[2] | |||||||||||

| Chancellor | The Princess Royal (as Chancellor of the University of London) | |||||||||||

| Provost | Michael Arthur | |||||||||||

| Chair of the Council | Dame DeAnne Julius[3] | |||||||||||

Academic staff | 7,700 (2018/19)[4] | |||||||||||

Administrative staff | 5,375 (2018/19)[4] | |||||||||||

| Students | 41,180 (2018/19)[5] | |||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 20,005 (2018/19)[5] | |||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 21,175 (2018/19)[5] | |||||||||||

| Location | ||||||||||||

| Visitor | Terence Etherton (as Master of the Rolls ex officio)[6] | |||||||||||

| Colours | ||||||||||||

| Affiliations | ||||||||||||

| Website | ucl | |||||||||||

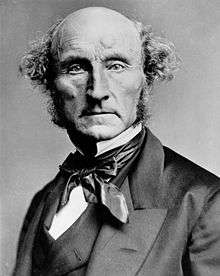

Established in 1826 as London University by founders inspired by the radical ideas of Jeremy Bentham, UCL was the first university institution to be established in London, and the first in England to be entirely secular and to admit students regardless of their religion.[10][11] UCL also makes the contested claims of being the third-oldest university in England[note 1] and the first to admit women.[note 2] In 1836 UCL became one of the two founding colleges of the University of London, which was granted a royal charter in the same year. It has grown through mergers, including with the Institute of Ophthalmology (in 1995), the Institute of Neurology (in 1997), the Royal Free Hospital Medical School (in 1998), the Eastman Dental Institute (in 1999), the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (in 1999), the School of Pharmacy (in 2012) and the Institute of Education (in 2014).

UCL has its main campus in the Bloomsbury area of central London, with a number of institutes and teaching hospitals elsewhere in central London and satellite campuses in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in Stratford, east London and in Doha, Qatar. UCL is organised into 11 constituent faculties, within which there are over 100 departments, institutes and research centres. UCL operates several museums and collections in a wide range of fields, including the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology and the Grant Museum of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy, and administers the annual Orwell Prize in political writing. In 2017/18, UCL had around 41,500 students and 15,100 staff (including around 7,100 academic staff and 840 professors) and had a total group income of £1.45 billion, of which £476.3 million was from research grants and contracts.[2]

UCL is a member of numerous academic organisations, including the Russell Group and the League of European Research Universities, and is part of UCL Partners, the world's largest academic health science centre,[12] and the "golden triangle" of research-intensive English universities.[13]

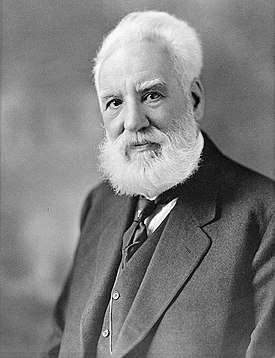

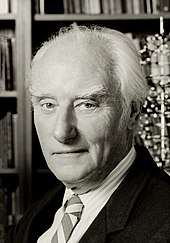

UCL alumni include the respective "Fathers of the Nation" of India, Kenya and Mauritius, the founders of Ghana, modern Japan and Nigeria, the inventor of the telephone, and one of the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA. UCL academics discovered five of the naturally occurring noble gases, discovered hormones, invented the vacuum tube, and made several foundational advances in modern statistics. As of 2020, 33 Nobel Prize winners and 3 Fields medalists have been affiliated with UCL as alumni, faculty or researchers.[note 3]

History

1826 to 1836 – London University

UCL was founded on 11 February 1826 under the name London University, as an alternative to the Anglican universities of Oxford and Cambridge.[14][15][16] London University's first Warden was Leonard Horner, who was the first scientist to head a British university.[17]

Despite the commonly held belief that the philosopher Jeremy Bentham was the founder of UCL, his direct involvement was limited to the purchase of share No. 633, at a cost of £100 paid in nine instalments between December 1826 and January 1830. In 1828 he did nominate a friend to sit on the council, and in 1827 attempted to have his disciple John Bowring appointed as the first professor of English or History, but on both occasions his candidates were unsuccessful.[18] This suggests that while his ideas may have been influential, he himself was less so. However, Bentham is today commonly regarded as the "spiritual father" of UCL, as his radical ideas on education and society were the inspiration to the institution's founders, particularly the Scotsmen James Mill (1773–1836) and Henry Brougham (1778–1868).[19]

In 1827, the Chair of Political Economy at London University was created, with John Ramsay McCulloch as the first incumbent, establishing one of the first departments of economics in England.[20] In 1828 the university became the first in England to offer English as a subject[21] and the teaching of Classics and medicine began. In 1830, London University founded the London University School, which would later become University College School. In 1833, the university appointed Alexander Maconochie, Secretary to the Royal Geographical Society, as the first professor of geography in the UK. In 1834, University College Hospital (originally North London Hospital) opened as a teaching hospital for the university's medical school.[22]

1836 to 1900 – University College, London

In 1836, London University was incorporated by royal charter under the name University College, London. On the same day, the University of London was created by royal charter as a degree-awarding examining board for students from affiliated schools and colleges, with University College and King's College, London being named in the charter as the first two affiliates.[23]

The Slade School of Fine Art was founded as part of University College in 1871, following a bequest from Felix Slade.[24]

In 1878, the University of London gained a supplemental charter making it the first British university to be allowed to award degrees to women. The same year, UCL admitted women to the faculties of Arts and Law and of Science, although women remained barred from the faculties of Engineering and of Medicine (with the exception of courses on public health and hygiene).[25][26] While UCL claims to have been the first university in England to admit women on equal terms to men, from 1878, the University of Bristol also makes this claim, having admitted women from its foundation (as a college) in 1876.[27] Armstrong College, a predecessor institution of Newcastle University, also allowed women to enter from its foundation in 1871, although none actually enrolled until 1881.[28] Women were finally admitted to medical studies during the First World War in 1917, although limitations were placed on their numbers after the war ended.[29]

In 1898, Sir William Ramsay discovered the elements krypton, neon and xenon whilst professor of chemistry at UCL.[30][31]

1900 to 1976 – University of London, University College

In 1900, the University of London was reconstituted as a federal university with new statutes drawn up under the University of London Act 1898. UCL, along with a number of other colleges in London, became a school of the University of London. While most of the constituent institutions retained their autonomy, UCL was merged into the University in 1907 under the University College London (Transfer) Act 1905 and lost its legal independence.[32] Its formal name became University of London, University College, although for most informal and external purposes the name "University College, London" (or the initialism UCL) was still used.

1900 also saw the decision to appoint a salaried head of the college. The first incumbent was Carey Foster, who served as Principal (as the post was originally titled) from 1900 to 1904. He was succeeded by Gregory Foster (no relation), and in 1906 the title was changed to Provost to avoid confusion with the Principal of the University of London. Gregory Foster remained in post until 1929.[33][34][35] In 1906, the Cruciform Building was opened as the new home for University College Hospital.[36]

UCL sustained considerable bomb damage during the Second World War, including the complete destruction of the Great Hall and the Carey Foster Physics Laboratory. Fires gutted the library and destroyed much of the main building, including the dome. The departments were dispersed across the country to Aberystwyth, Bangor, Gwynedd, Cambridge, Oxford, Rothamsted near Harpenden, Hertfordshire and Sheffield, with the administration at Stanstead Bury near Ware, Hertfordshire.[37] The first UCL student magazine, Pi, was published for the first time on 21 February 1946. The Institute of Jewish Studies relocated to UCL in 1959.

The Mullard Space Science Laboratory was established in 1967.[38] In 1973, UCL became the first international node to the precursor of the internet, the ARPANET.[39][40]

Although UCL was among the first universities to admit women on the same terms as men, in 1878, the college's senior common room, the Housman Room, remained men-only until 1969. After two unsuccessful attempts, a motion was passed that ended segregation by sex at UCL. This was achieved by Brian Woledge (Fielden Professor of French at UCL from 1939 to 1971) and David Colquhoun, at that time a young lecturer in pharmacology.[41]

1976 to 2005 – University College London

In 1976, a new charter restored UCL's legal independence, although still without the power to award its own degrees.[42][43] Under this charter the college became formally known as University College London. This name abandoned the comma used in its earlier name of "University College, London".

In 1986, UCL merged with the Institute of Archaeology.[44] In 1988, UCL merged with the Institute of Laryngology & Otology, the Institute of Orthopaedics, the Institute of Urology & Nephrology and Middlesex Hospital Medical School.[44]

In 1993, a reorganisation of the University of London meant that UCL and other colleges gained direct access to government funding and the right to confer University of London degrees themselves. This led to UCL being regarded as a de facto university in its own right.[45]

In 1994, the University College London Hospitals NHS Trust was established.[46] UCL merged with the College of Speech Sciences and the Institute of Ophthalmology in 1995, the Institute of Child Health and the School of Podiatry in 1996[47] and the Institute of Neurology in 1997.[44][48] In 1998, UCL merged with the Royal Free Hospital Medical School to create the Royal Free and University College Medical School (renamed the UCL Medical School in October 2008). In 1999, UCL merged with the School of Slavonic and East European Studies[49][50] and the Eastman Dental Institute.[44]

The UCL Jill Dando Institute of Crime Science, the first university department in the world devoted specifically to reducing crime, was founded in 2001.[51]

Proposals for a merger between UCL and Imperial College London were announced in 2002.[52] The proposal provoked strong opposition from UCL teaching staff and students and the AUT union, which criticised "the indecent haste and lack of consultation", leading to its abandonment by the UCL provost Sir Derek Roberts.[53] The blogs that helped to stop the merger are preserved, though some of the links are now broken: see David Colquhoun's blog[54] and the Save UCL blog,[55] which was run by David Conway, a postgraduate student in the department of Hebrew and Jewish studies.

The London Centre for Nanotechnology was established in 2003 as a joint venture between UCL and Imperial College London.[56][57] They were later joined by King's College London in 2018.[58]

Since 2003, when UCL professor David Latchman became master of the neighbouring Birkbeck, he has forged closer relations between these two University of London colleges, and personally maintains departments at both. Joint research centres include the UCL/Birkbeck Institute for Earth and Planetary Sciences, the UCL/Birkbeck/IoE Centre for Educational Neuroscience, the UCL/Birkbeck Institute of Structural and Molecular Biology, and the Birkbeck-UCL Centre for Neuroimaging.

2005 to 2010

In 2005, UCL was finally granted its own taught and research degree awarding powers and all UCL students registered from 2007/08 qualified with UCL degrees. Also in 2005, UCL adopted a new corporate branding under which the name University College London was replaced by the initialism UCL in all external communications.[59] In the same year, a major new £422 million building was opened for University College Hospital on Euston Road,[60] the UCL Ear Institute was established and a new building for the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies was opened.

In 2007, the UCL Cancer Institute was opened in the newly constructed Paul O'Gorman Building. In August 2008, UCL formed UCL Partners, an academic health science centre, with Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust, Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust and University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.[61] In 2008, UCL established the UCL School of Energy & Resources in Adelaide, Australia, the first campus of a British university in the country.[62] The School was based in the historic Torrens Building in Victoria Square and its creation followed negotiations between UCL Vice Provost Michael Worton and South Australian Premier Mike Rann.[63]

In 2009, the Yale UCL Collaborative was established between UCL, UCL Partners, Yale University, Yale School of Medicine and Yale – New Haven Hospital.[64] It is the largest collaboration in the history of either university, and its scope has subsequently been extended to the humanities and social sciences.[65][66]

2010 to 2015

In June 2011, the mining company BHP Billiton agreed to donate AU$10 million to UCL to fund the establishment of two energy institutes – the Energy Policy Institute, based in Adelaide, and the Institute for Sustainable Resources, based in London.[67]

In November 2011, UCL announced plans for a £500 million investment in its main Bloomsbury campus over 10 years, as well as the establishment of a new 23-acre campus next to the Olympic Park in Stratford in the East End of London.[68] It revised its plans of expansion in East London and in December 2014 announced to build a campus (UCL East) covering 11 acres and provide up to 125,000m2 of space on Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.[69] UCL East will be part of plans to transform the Olympic Park into a cultural and innovation hub, where UCL will open its first school of design, a centre of experimental engineering and a museum of the future, along with a living space for students.[70]

The School of Pharmacy, University of London merged with UCL on 1 January 2012, becoming the UCL School of Pharmacy within the Faculty of Life Sciences.[71][72] In May 2012, UCL, Imperial College London and the semiconductor company Intel announced the establishment of the Intel Collaborative Research Institute for Sustainable Connected Cities, a London-based institute for research into the future of cities.[73][74]

In August 2012, UCL received criticism for advertising an unpaid research position; it subsequently withdrew the advert.[75]

UCL and the Institute of Education formed a strategic alliance in October 2012, including co-operation in teaching, research and the development of the London schools system.[76] In February 2014, the two institutions announced their intention to merge,[77][78] and the merger was completed in December 2014.[79][80]

In September 2013, a new Department of Science, Technology, Engineering and Public Policy (STEaPP) was established within the Faculty of Engineering, one of several initiatives within the university to increase and reflect upon the links between research and public sector decision-making.[81]

In October 2013, it was announced that the Translation Studies Unit of Imperial College London would move to UCL, becoming part of the UCL School of European Languages, Culture and Society.[82] In December 2013, it was announced that UCL and the academic publishing company Elsevier would collaborate to establish the UCL Big Data Institute.[83] In January 2015, it was announced that UCL had been selected by the UK government as one of the five founding members of the Alan Turing Institute (together with the universities of Cambridge, Edinburgh, Oxford and Warwick), an institute to be established at the British Library to promote the development and use of advanced mathematics, computer science, algorithms and big data.[84][85]

2015 to present

In August 2015, the Department of Management Science and Innovation was renamed as the School of Management and plans were announced to greatly expand UCL's activities in the area of business-related teaching and research.[86][87] The school moved from the Bloomsbury campus to One Canada Square in Canary Wharf in 2016.[88]

UCL established the Institute of Advanced Studies (IAS) in 2015 to promote interdisciplinary research in humanities and social sciences. The prestigious annual Orwell Prize for political writing moved to the IAS in 2016.

In June 2016 it was reported in the Times Higher Education that as a result of administrative errors hundreds of students who studied at the UCL Eastman Dental Institute between 2005–6 and 2013–14 had been given the wrong marks, leading to an unknown number of students being attributed with the wrong qualifications and, in some cases, being failed when they should have passed their degrees.[89] A report by UCL's Academic Committee Review Panel noted that, according to the Institute's own review findings, senior members of UCL staff had been aware of issues affecting students' results but had not taken action to address them.[90] The Review Panel concluded that there had been an apparent lack of ownership of these matters amongst the Institute's senior staff.[90]

In December 2016 it was announced that UCL would be the hub institution for a new £250 million national dementia research institute, to be funded with £150 million from the Medical Research Council and £50 million each from Alzheimer's Research UK and the Alzheimer's Society.[91][92]

In May 2017 it was reported that staff morale was at "an all time low", with 68% of members of the academic board who responded to a survey disagreeing with the statement "UCL is well managed" and 86% with "the teaching facilities are adequate for the number of students". Michael Arthur, the Provost and President, linked the results to the "major change programme" at UCL. He admitted that facilities were under pressure following growth over the past decade, but said that the issues were being addressed through the development of UCL East and rental of other additional space.[93]

In October 2017 UCL's council voted to apply for university status while remaining part of the University of London.[94] UCL's application to become a university is subject to Parliament passing a bill to amend the statutes of the University of London, which is, as of July 2018, held up by procedural issues in the House of Commons.[95][96] The bill received royal assent on 20 December 2018, allowing UCL's application for university status to proceed.[97]

The UCL Adelaide satellite campus closed in December 2017, with academic staff and student transferring to the University of South Australia.[98] As of 2019 UniSA and UCL are offering a joint masters qualification in Science in Data Science (international).[99]

In 2018, UCL opened UCL at Here East, at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, offering courses jointly between the Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment and the Faculty of Engineering Sciences.[100] The campus offers a variety of undergraduate and postgraduate master's degrees,[101] with the first undergraduate students, on a new Engineering and Architectural Design MEng, starting in September 2018.[102] It was announced in August 2018 that a £215 million contract for construction of the largest building in the UCL East development, Marshgate 1, had been awarded to Mace, with building to begin in 2019 and be completed by 2022.[103]

In 2017 UCL disciplined an IT administrator who was also the University and College Union (UCU) branch secretary for refusing to take down an unmoderated staff mailing list. An employment tribunal subsequently ruled that he was engaged in union activities and thus this disciplinary action was unlawful. As of June 2019 UCL is appealing this ruling and the UCU congress has declared this to be a "dispute of national significance".[104]

Campus and locations

Bloomsbury

.jpg)

UCL is primarily based in the Bloomsbury area of the London Borough of Camden, in Central London. The main campus is located around Gower Street and includes the biology, chemistry, economics, engineering, geography, history, languages, mathematics, management, philosophy and physics departments, the preclinical facilities of the UCL Medical School, the London Centre for Nanotechnology, the Slade School of Fine Art, the UCL Union, the main UCL Library, the UCL Science Library, the Bloomsbury Theatre, the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, the Grant Museum of Zoology and the affiliated University College Hospital. Close by in Bloomsbury are the UCL Cancer Institute, the UCL Faculty of the Built Environment (The Bartlett), the UCL Faculty of Laws, the UCL Institute of Archaeology, the UCL Institute of Education, the UCL School of Pharmacy, the UCL School of Public Policy and the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies.[105]

The area around Queen Square in Bloomsbury, close by to the main campus, is a hub for brain-related research and healthcare, with the UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and UCL Institute of Neurology located in the area along with the affiliated National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery. The UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health and the affiliated Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children are located adjacently, forming a hub for paediatric research and healthcare. The UCL Ear Institute, the UCL Eastman Dental Institute and the affiliated Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital and Eastman Dental Hospital are located nearby in east Bloomsbury along Gray's Inn Road and form a hub for research and healthcare in audiology and dentistry respectively.

Notable UCL buildings in Bloomsbury include the UCL Main Building, including the Octagon, Quad, Cloisters and the Wilkins building designed by William Wilkins; the Cruciform Building, Gower Street (a red, cross-shaped building previously home to University College Hospital); and the Rockefeller Building, University Street, home to the original University College Hospital Medical School and named after the American oil magnate John D. Rockefeller after support from the Rockefeller Foundation in the 1920s. Due to its position within London and the historical nature of its buildings, including most notably the UCL Main Building and Quad, UCL has been used as a location for a number of film and television productions, including Doctor in the House (1954), Gladiator (2000), The Mummy Returns (2001), The Dark Knight (2008) and Inception (2010).[106]

A number of important institutions are based near to the main campus, including the British Library, the British Medical Association, the British Museum, Cancer Research UK, Gray's Inn, the Medical Research Council, RADA, the Royal Academy of Art, the Royal Institution and the Wellcome Trust. Many University of London schools and institutes are also close by, including Birkbeck, University of London, London Business School, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, the Royal Veterinary College, the School of Advanced Study, the School of Oriental and African Studies and the Senate House Library. The nearest London Underground station is Euston Square, with Goodge Street, Russell Square, Tottenham Court Road and Warren Street all nearby. The mainline railway stations at Euston, King's Cross and St Pancras are all within walking distance.

UCL East

In 2014 it was announced that UCL would be building an additional campus at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, referred to as UCL East, as part of the development of the so-called Olympicopolis site at the southern edge of the park. UCL master planners were appointed in spring 2015, and the first University building was, at that time, estimated to be completed in time for academic year 2019/20.[107]

It was revealed in June 2016 that the UCL East expansion could see the university grow to 60,000 students. The proposed rate of growth was reported to be causing concern, with calls for it to be slowed down to ensure the university could meet financial stability targets.[108]

Outline planning permission for UCL East was submitted in May 2017 by the London Legacy Development Corporation and UCL, and granted in March 2018. Construction of the first phase of buildings is (as of March 2018) expected to begin in 2019 with the first building (Pool Street West) expected to be completed for the start of the 2021 academic year and the second building (Marshgate 1) opening in phases from September 2022. As of March 2018, phase 1 is intended to have 50,000 m2 of space, and to house 4,000 extra students and 260 extra academic staff, while the entire UCL East campus, when completed, is expected to have 180,000 m2 of space, 40% of the size of UCL's central London campus.[109] The outline planning permission is for up to 190,800 m2 of space with up to 160,060 m2 of academic development and research space (including up to 16,000 m2 of commercial research space), up to 50,880 m2 of student accommodation, and up to 4,240 m2 of retail space.[110] According to the planning documents, construction of phase 2 (Pool Street East and Marshfield 2, 3 and 4) is expected to begin in 2030 and be completed by 2034, and the whole project will support 2,337 academic staff and 11,169 students.[111] The campus will include residences for up to 1,800 students.[112] In June 2018, UCL revealed that the UK Government would be providing £100 million of funding for UCL East as part of its £151 million contribution to the £1.1 billion redevelopment of the Olympic Park as a cultural and education district to be known as the East Bank.[113][114] Construction work on UCL East began on 2 July 2019 with a ground breaking ceremony by the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan,[115] and work on Pool Street West began on 28 February 2020.[116]

From 2018 UCL is offering degree courses at the Olympic Park, based at UCL at Here East at the northern end of the East Bank development.[100]

Other sites

Elsewhere in Central London are the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology (based in Clerkenwell), the Windeyer Institute (based in Fitzrovia), the UCL Institute of Orthopedics and Musculoskeletal Science (based in Stanmore), The Royal Free Hospital and the Whittington Hospital campuses of the UCL Medical School, and a number of other teaching hospitals. The UCL School of Management is located at Level 38, One Canada Square located in the financial district of Canary Wharf, London. The Department of Space and Climate Physics (Mullard Space Science Laboratory) is based in Holmbury St Mary, Surrey, and there is a UCL campus in Doha, Qatar specialised in archaeology, conservation, museum and gallery practice, and library and information studies that will close in 2020 at the end of UCL's contact with the Qatar Foundation).[117][118][119] From 2010 to 2015 UCL ran a University Preparatory Certificate course at Nazarbayev University in Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan,[120] and had a campus in Adelaide, Australia from 2010 to 2017.[121]

Organisation and administration

Governance

Although UCL is a constituent college of the federal University of London, in most ways it is comparable with free-standing, self-governing and independently funded universities, and it awards its own degrees.[122]

UCL's governing body is the council, which oversees the management and administration of UCL and the conduct of its affairs, subject to the advice of the academic board on matters of academic policy, and approves UCL's long-term plans.[123] It delegates authority to the provost, as chief executive, for the academic, corporate, financial, estate and human resources management of UCL. The Council normally meets six times each year. The Council comprises 20 members, of whom 11 are members external to UCL; seven are UCL academic staff, including the provost, three UCL professors and three non-professorial staff; and two are UCL students. The chair is appointed by council for a term not normally exceeding five years. The chair is ex officio chair of the honorary degrees and fellowships committee, nominations committee and remuneration and strategy committee.[123] The current chair of the council is Dame DeAnne Julius.

UCL's principal academic and administrative officer is the president and provost, who is also UCL's designated principal officer for the purposes of the financial memorandum with the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE).[123] The provost is appointed by council after consultation with the academic board, is responsible to the council, and works closely with its members, and especially with the chair of council. The current and tenth provost and president of UCL is Michael Arthur, who replaced Sir Malcolm Grant in 2013.[124]

Vice-provosts are appointed by the provost, through the council, to assist and advise the provost as required. The vice-provosts are members of the provost's senior management team. There are presently six vice-provosts (for education, enterprise, health, international, research, and operations).[123]

The deans of UCL's faculties are appointed by the council and, together with the vice-provosts and the director of finance and business affairs, form the members of the provost's senior management team. The deans' principal duties include advising the provost and vice-provosts on academic strategy, staffing matters and resources for academic departments within their faculty; overseeing curricula and programme management at faculty level; liaising with faculty tutors on undergraduate admissions and student academic matters; overseeing examination matters at faculty level; and co-ordinating faculty views on matters relating to education and information support.[123]

List of provosts

- Sir Gregory Foster (1906–1929)[35]

- Sir Allen Mawer (1930–1942)[35]

- David Pye (1943–1951)[35]

- Sir Ifor Evans (1951–1966)[35]

- Lord Annan (1966–1978)[35]

- Sir James Lighthill (1979–1989)[35]

- Sir Derek Roberts (1989–1999;[35] 2002–2003)

- Sir Christopher Llewellyn Smith (1999–2002)[35]

- Sir Malcolm Grant (2003–2013)[35]

- Michael Arthur (2013–present)

Faculties and departments

UCL's research and teaching is organised within a network of faculties and academic departments. Faculties and academic departments are formally established by the UCL Council, the governing body of UCL, on the advice of the Academic Board, which is UCL's senior academic authority. UCL is a comprehensive university with teaching and research across the full range of the arts, humanities, social sciences, physical, biological and medical sciences, engineering and the built environment, although it does not currently have a veterinary, music, drama or nursing school.[125] UCL is currently organised into the following 11 constituent faculties:[126]

| Faculty[127] | Academic and research staff (as at 30 April 2012)[127] |

Undergraduate students (2011/12)[127] |

Postgraduate students (2011/12)[127] |

| UCL Faculty of Arts and Humanities | 328 | 2,157 | 1,075 |

| UCL Faculty of Brain Sciences | 1,249 | 722 | 1,457 |

| UCL Faculty of the Built Environment (The Bartlett) | 355 | 570 | 1,241 |

| UCL Faculty of Engineering Sciences | 667 | 2,049 | 1,642 |

| UCL Faculty of Laws | 137 | 528 | 458 |

| UCL Faculty of Life Sciences | 798 | 1,183 | 486 |

| UCL Faculty of Mathematical and Physical Sciences | 754 | 2,187 | 677 |

| UCL Faculty of Medical Sciences | 1,257 | 1,773 | 1,342 |

| UCL Faculty of Population Health Sciences | 1,092 | 64 | 815 |

| UCL Faculty of Social and Historical Sciences | 621 | 2,539 | 1,894 |

| UCL Institute of Education | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Total | 5,277 (ex. Institute of Education) | 13,772 (ex. Institute of Education) | 11,087 (ex. Institute of Education) |

To facilitate greater interdisciplinary interaction in research and teaching UCL also has four strategic faculty groupings:

- the UCL School of Life and Medical Sciences (comprising the Faculties of Brain Sciences, Life Sciences, Medical Sciences and Population Health Sciences);

- the UCL School of the Built Environment, Engineering and Mathematical and Physical Sciences (comprising the UCL Faculty of the Built Environment, UCL Faculty of Engineering Sciences and UCL Faculty of Mathematical & Physical Sciences);

- the UCL Faculty of Arts & Humanities, UCL Faculty of Laws, UCL Faculty of Social & Historical Sciences and the UCL School of Slavonic & East European Studies.

- the UCL Institute of Education

Finances

In the financial year ended 31 July 2016, UCL had a total income (excluding share of joint ventures) of £1.36 billion (2014/15 – £1.26 billion) and a total expenditure of £1.23 billion (2014/15 – £1.22 billion).[2] Key sources of income included £530.4 million from research grants and contracts (2014/15 – £427.3 million), £421.1 million from tuition fees and education contracts (2014/15 – £364.2 million), £192.1 million from funding body grants (2014/15 – £195.2 million) and £25.1 million from donations and endowments (2014/15 – £20.3 million).[2] During the 2015/16 financial year UCL had a capital expenditure of £146.6 million (2014/15 – £149.3 million).[2] At year end UCL had endowments of £100.9 million (31 July 2015 – £104.1 million) and total net assets of £1.19 billion (31 July 2015 – £1.07 million).[2][note 4]

In 2014/15, UCL had the third-highest total income of any British university (after the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford), and the third-highest income from research grants and contracts (after the University of Oxford and Imperial College London).[128] For the 2015/16 academic year, UCL was allocated a total of £171.37 million for teaching and research from the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), the highest amount allocated to any English university, of which £39.76 million is for teaching and £131.61 million is for research.[129] According to a survey published by the Sutton Trust, UCL had the eighth-largest endowment of any British university in 2012.[130]

UCL launched a 10-year, £300 million fundraising appeal in October 2004, at the time the largest appeal target set by a university in the United Kingdom.[131] UCL launched a new £600 million fundraising campaign in September 2016 titled "It's All Academic – The Campaign for UCL".[132][133]

In April 2016, UCL signed a £280 million 30-year loan with the European Investment Bank, the largest loan ever borrowed by a UK university and largest ever loan by the EIB to a university.[134][135] The monies are to be used to fund a £1.25 billion capital expenditure programme in Bloomsbury and Stratford.[134][135] Some UCL academics oppose the expansion plans.[136]

Terms

The UCL academic year is divided into three terms.[137] For most departments except the Medical School, Term One runs from late September to mid December, Term Two from mid January to late March, and Term Three from late April to mid June.[137] Certain departments operate reading weeks in early November and mid February. Term 3 is widely dedicated for summer assessments only. The venue used to cope with the great numbers of students sitting exams is the ExCeL London conference centre in East London [138] [137]

Logo, arms and colours

Whereas most universities primarily use their logo on mundane documents but their coat of arms on official documents such as degree certificates, UCL exclusively uses its logo. The present logo was adopted as part of a rebranding exercise in August 2005.[59] Prior to that date, a different logo was used, in which the letters UCL were incorporated into a stylised representation of the Wilkins Building portico.

UCL formerly made some use of a pseudo-heraldic "coat of arms" depicting a raised bent arm dressed in armour holding a green upturned open wreath.[139] A version of this badge (not on a shield) appears to have been used by UCL Union from shortly after its foundation in 1893.[140] However, the arms have never been the subject of an official grant of arms, and depart from several of the rules and conventions of heraldry. They are no longer formally used by the college, although they are still occasionally seen in unofficial contexts, or used in modified form by sports teams and societies. The blazon of the arms might be rendered as: Purpure, on a wreath of the colours Argent and Blue Celeste, an arm in armour embowed Argent holding an upturned wreath of laurel Vert, beneath which two branches of laurel Or crossed at the nombril and bound with a bowed cord Or, beneath the nombril a motto of Blue Celeste upon which Cuncti adsint meritaeque expectent praemia palmae. The motto is a quotation from Virgil's Aeneid, and translates into English as "Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward".[141]

UCL's traditional sporting and academic colours of purple [rgb(96,40,153)] and light blue [rgb(102,204,255)] are derived from the arms.

Former UCL logo, in use until 2005

Former UCL logo, in use until 2005 UCL "coat of arms"

UCL "coat of arms" UCL scarf colours

UCL scarf colours

Secularism

From its foundation the college was deliberately secular; the initial justification for this was that it would enable students of different Christian traditions (specifically Roman Catholics, Anglicans and Protestants) to study alongside each other without conflict.[142] UCL has retained this strict secular position and, unlike most other UK universities, has no specific religious prayer rooms. There is, however, a Christian chaplain (who also serves as interfaith advisor) and there is no restriction on religious groups among students. A "quiet contemplation room" also allows prayer for staff and students of all faiths.[143][144]

Sexual Harassment Cases and Policies

In recent years, the University has paid tens of thousands of pounds to settle sexual harassment claims but announced in 2018 that it would abandon non-disclosure settlements.[145]The University made the decision after physicist Emma Chapman sued the institution for sexual harassment though the law firm of Ann Olivarius and then won the legal right to speak freely about her abuse at the University. Chapman settled the case for £70,000.[146] In 2020, UCL became the first Russell Group university to ban romantic and sexual relationships between lecturers and their students.[147]

Memberships, affiliations and partnerships

UCL is a constituent college of the federal University of London, of which it was one of the two founding members in 1836 (the other being King's College London).[148]

UCL is a founding member of the Russell Group, an association of 24 British research universities established in 1994,[149] and of the G5 lobbying group, which it established in early 2004 with the universities of Cambridge and Oxford, Imperial College London and the London School of Economics.[150][151] UCL is regarded as forming part of the ‘golden triangle’, an unofficial term for a set of leading universities located in the southern English cities of Cambridge, London and Oxford[152][153][154] including the universities of Cambridge and Oxford, Imperial College London, King's College London and the London School of Economics.

UCL has been a member of the League of European Research Universities since January 2006. It is currently one of five British members (the others being the universities of Cambridge, Edinburgh and Oxford and Imperial College London).[155][156] Other international groupings that UCL is a member of include the Association of Commonwealth Universities, the European University Association and the Universities Research Association.[157] UCL has a major collaboration with Yale University, the Yale UCL Collaborative, and has hundreds of other research and teaching partnerships, including around 150 research links and 130 student-exchange partnerships with European universities.[158]

UCL has been a member of the SES engineering and physical sciences research alliance since May 2013, which it formed with the universities of Cambridge, Oxford and Southampton and Imperial College London (King's College London subsequently joined in 2016).[159] UCL is a member of the Thomas Young Centre, an alliance of London research groups working on the theory and simulation of materials; the other members are Imperial College London, King's College London and Queen Mary University of London.[160] UCL is one of the five founding members of the Alan Turing Institute, the UK's national institute for data sciences (together with the universities of Cambridge, Edinburgh, Oxford and Warwick).[161] It also operates the London Centre for Nanotechnology, a multidisciplinary research centre in physical and biomedical nanotechnology, in partnership with Imperial College London.[162]

UCL has a close partnership with University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; the Trust's hospitals are teaching sites for the UCL Medical School, UCL and the Trust are joint partners in the UCLH/UCL Biomedical Research Centre and the Institute of Sport, Exercise and Health,[163] and both are members of the UCL Partners academic health science centre.[12][164][165] UCL is a founding member of the Francis Crick Institute, a major biomedical research centre in London which is a partnership between Cancer Research UK, Imperial College London, King's College London, the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust and UCL.[166] UCL also operates the Bloomsbury Research Institute, a research institute focused on basic to clinical and population studies in bacteriology, parasitology and virology, in partnership with the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.[167]

UCL offers joint degrees with numerous other universities and institutions, including The Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families,[168] Columbia University,[169] the University of Hong Kong,[170] Imperial College London,[171] New York University,[172] Peking University[173] and Yale University.[174]

UCL is the sponsor of the UCL Academy, a secondary school in the London Borough of Camden. The school opened in September 2012 and was the first in the UK to have a university as sole sponsor.[175] UCL also has a strategic partnership with Newham Collegiate Sixth Form Centre.[176]

UCL is a founding member of Knowledge Quarter, a partnership of academic, cultural, research, scientific and media organisations based in the knowledge cluster in the Bloomsbury and King's Cross area of London.[177] Other members of the partnership include the British Library, the British Museum, Google and the Wellcome Trust.[177]

The university is also a member of the Screen Studies Group, London.

Academics

Faculty and staff

In the 2018/19 academic year, UCL had an average of 7,700 academic and research staff, the highest number of any UK university, of whom 5,845 were full-time and 1,855 part-time.[4] UCL has 840 professors, the largest number of any British university.[178] As of August 2016 there were 56 Fellows of the Royal Society, 51 Fellows of the British Academy, 15 Fellows of the Royal Academy of Engineering and 121 Fellows of the Academy of Medical Sciences amongst UCL academic and research staff.[178]

Research

_2014.jpg)

UCL has made cross-disciplinary research a priority and orientates its research around four "Grand Challenges", Global Health, Sustainable Cities, Intercultural Interaction and Human Wellbeing.[179]

In 2014/15, UCL had a total research income of £427.5 million, the third-highest of any British university (after the University of Oxford and Imperial College London).[128] Key sources of research income in that year were BIS research councils (£148.3 million), UK-based charities (£106.5 million), UK central government, local/health authorities and hospitals (£61.5 million), EU government bodies (£45.5 million), and UK industry, commerce and public corporations (£16.2 million).[2] In 2015/16, UCL was awarded a total of £85.8 million in grants by UK research councils, the second-largest amount of any British university (after the University of Oxford), having achieved a 28% success rate.[180] For the period to June 2015, UCL was the fifth-largest recipient of Horizon 2020 EU research funding, and the largest recipient of any university, with €49.93 million of grants received.[181] UCL also had the fifth-largest number of projects funded of any organisation, with 94.[181]

According to a ranking of universities produced by SCImago Research Group, UCL is ranked 12th in the world (and 1st in Europe) in terms of total research output.[182] According to data released in July 2008 by ISI Web of Knowledge, UCL is the 13th most-cited university in the world (and most-cited in Europe). The analysis covered citations from 1 January 1998 to 30 April 2008, during which 46,166 UCL research papers attracted 803,566 citations. The report covered citations in 21 subject areas and the results revealed some of UCL's key strengths, including: Clinical Medicine (1st outside North America); Immunology (2nd in Europe); Neuroscience & Behaviour (1st outside North America and 2nd in the world); Pharmacology & Toxicology (1st outside North America and 4th in the world); Psychiatry & Psychology (2nd outside North America); and Social Sciences, General (1st outside North America).[183]

UCL submitted a total of 2,566 staff across 36 units of assessment to the 2014 Research Excellence Framework (REF) assessment, in each case the highest number of any UK university (compared with 1,793 UCL staff submitted to the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise (RAE 2008)).[184][185] In the REF results 43% of UCL's submitted research was classified as 4* (world-leading), 39% as 3* (internationally excellent), 15% as 2* (recognised internationally) and 2% as 1* (recognised nationally), giving an overall GPA of 3.22 (RAE 2008: 4* – 27%, 3* – 39%, 2* – 27% and 1* – 6%).[185][186][187] In rankings produced by Times Higher Education based upon the REF results, UCL was ranked 1st overall for "research power" and joint 8th for GPA (compared to 4th and 7th respectively in equivalent rankings for the RAE 2008).[187]

Medicine

UCL has offered courses in medicine since 1834, but the current UCL Medical School developed from mergers with the medical schools of the Middlesex Hospital (founded in 1746) and the Royal Free Hospital (founded as the London School of Medicine for Women in 1874).[188] Clinical medicine is primarily taught at the Royal Free Hospital, University College Hospital and the Whittington Hospital, with other associated teaching hospitals including the Eastman Dental Hospital, Great Ormond Street Hospital, Moorfields Eye Hospital, the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and the Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital.

UCL is a major centre for biomedical research. In a bibliometric analysis of biomedical and health research in England for the period 2004–13, UCL was found to have produced by far the highest number of highly cited publications of any institution, with 12,672 (compared to second-placed Oxford University with 9,952).[189] UCL is part of three of the 20 biomedical research centres established by the NHS in England – the UCLH/UCL Biomedical Research Centre, the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, and the NIHR Great Ormond Street Biomedical Research Centre.[190] In the latest round of Department of Health funding for the 5 years from April 2017, the three UCL-affiliated biomedical research centres secured £168.6 million of the £811 million total funding nationwide, the largest amount awarded to any university and significantly higher than second-placed Oxford University (with £126.5 million).[191]

UCL is a founding member of UCL Partners, the largest academic health science centre in Europe with a turnover of approximately £2 billion.[192] UCL is also a member of the Francis Crick Institute based next to St Pancras railway station.[193] It is one of the world's largest medical research centres, housing 1,250 scientists, and the largest of its kind in Europe.[194]

Admissions

| 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applications[195] | 43,930 | 41,540 | 40,355 | 38,330 | 36,015 |

| Offer Rate (%)[196] | 62.9 | 63.0 | 61.7 | 56.7 | 55.6 |

| Enrols[197] | 6,140 | 5,590 | 5,455 | 5,030 | 4,900 |

| Yield (%) | 22.2 | 21.4 | 21.9 | 23.1 | 24.5 |

| Applicant/Enrolled Ratio | 7.15 | 7.43 | 7.40 | 7.62 | 7.35 |

| Average Entry Tariff[198][note 5] | n/a | 191 | 501 | 505 | 500 |

Admission to UCL is highly selective with an average entry tariff for 2018–19 of 175 UCAS points (approximately equivalent to AABB at A-level), the 11th highest in the country.[199] UCL was one of the first universities in the UK to make use of the A* grade at A-Level (introduced in 2010) for admissions to courses including Economics, European Social and Political Studies, Law, Mathematics, Medicine, Theoretical Physics and Psychology.[200] The university gave offers of admission to 62.9% of its applicants in 2017, and had the 6th lowest offer rate in the Russell Group in 2015.[201] For 2017 entry, the university was one of only a few mainstream universities (along with Cambridge, Imperial College London, LSE, Oxford, St Andrews, and Warwick) to have no courses available in Clearing.[202]

Of UCL's undergraduates, 32.4% are privately educated, the eighth highest proportion amongst mainstream British universities.[203] In the 2016–17 academic year, the university had a domicile breakdown of 59:12:30 of UK:EU:non-EU students respectively with a female to male ratio of 58:42.[204]

Undergraduate law applicants are required to take the National Admissions Test for Law[205] and undergraduate medical applicants are required to take the BioMedical Admissions Test.[206] Applicants for European Social and Political Studies are required to take the Thinking Skills Assessment (TSA) should they be selected for an assessment day.[207] Some UCL departments interview undergraduate applicants prior to making an offer of admission.[208]

Undergraduate subjects with the highest applicants to places ratio at UCL in 2015 included Architecture BSc (14:1 ratio),[209] Economics BSc (Econ) (11:1 ratio),[210] Engineering (Mechanical with Business Finance) MEng (10:1 ratio),[211] English BA (10:1 ratio),[212] Fine Art BA (23:1 ratio),[213] Law LL.B (16:1 ratio)[214] and Philosophy, Politics and Economics BSc (30:1 ratio).[215]

Foundation programmes

UCL runs intensive one-year foundation courses that lead to a variety of degree programmes at UCL and other top UK universities. Called the UCL University Preparatory Certificate, the courses are targeted at international students of high academic potential whose education systems in their own countries usually do not offer qualifications suitable for direct admission. There are two pathways – one in science and engineering called the UPCSE; and one in the humanities called UPCH. Students completing this course progress onto undergraduate programmes at Nazarbayev University.[216]

Libraries

The UCL library system comprises 17 libraries located across several sites within the main UCL campus and across Bloomsbury, linked together by a central networking catalogue and request system called Explore.[217][218][219] The libraries contain a total of over 2 million books.[220] The largest library is the UCL Main Library, which is located in the UCL Main Building and contains collections relating to the arts and humanities, economics, history, law and public policy.[217] The second largest library is the UCL Science Library, which is located in the DMS Watson Building on Malet Place and contains collections relating to anthropology, engineering, geography, life sciences, management and the mathematical and physical sciences.[217] The Cruciform Hub contains books and periodicals in the subjects of clinical medicine and medical science.[221] It holds the combined collections of the former Boldero and Clinical Sciences libraries which developed within the Middlesex Hospital, University College Hospital and Royal Free & University College Medical Schools up until their merger in 2005.[222] Other libraries include the UCL Bartlett Library (architecture and town planning), the UCL Eastman Dental Institute Library (oral health sciences), the UCL Institute of Archaeology Library (archaeology and egyptology), the UCL Institute of Education's Newsam Library (education and related areas of social science), the UCL Institute of Neurology Rockefeller Medical Library (neurosurgery and neuroscience), the Joint Moorfields Eye Hospital & the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology Library (biomedicine, medicine, nursing, ophthalmology and visual science), the UCL Language & Speech Science Library (audiology, communication disorders, linguistics & phonetics, special education, speech & language therapy and voice) and the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies Library (the economics, geography, history, languages, literature and politics of Eastern Europe).[217]

UCL staff and students have full access to the main libraries of the University of London—the Senate House Library and the libraries of the Institutes of the School of Advanced Study—which are located close to the main UCL campus in Bloomsbury.[223] These libraries contain over 3.7 million books and focus on the arts, humanities and social sciences.[220] The British Library, which contains around 14 million books, is also located close to the main UCL campus and all UCL students and staff can apply for reference access.[224]

Since 2004, UCL Library Services has been collecting the scholarly work of UCL researchers to make it freely available on the internet via an open access repository known as UCL Eprints.[225][226] The intention is that material curated by UCL Eprints will remain accessible indefinitely.[225]

Museums and collections

UCL's Special Collections contains UCL's collection of historical or culturally significant works. It is one of the foremost university collections of manuscripts, archives and rare books in the UK.[227] It includes collections of medieval manuscripts and early printed books, as well as significant holdings of 18th-century works, and highly important 19th- and 20th-century collections of personal papers, archival material, and literature, covering a vast range of subject areas. Archives include the Latin American archives, the Jewish collections and the George Orwell Archive.[228] Collections are often displayed in a series of glass cabinets in the Cloisters of the UCL Main Building.[229]

UCL's most significant works are housed in the Strong Rooms. The special collection includes first editions of Isaac Newton's Principia, Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species and James Joyce's Ulysses. The earliest book in the collection is The crafte to lyve well and to dye well, printed in 1505.[230]

UCL is responsible for several museums and collections in a wide range of fields across the arts and sciences, including:[231]

- Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology: one of the leading collections of Egyptian and Sudanese archaeology in the world. Open to the public on a regular basis.[232]

- UCL Art Museum: the art collections date from 1847, when a collection of sculpture models and drawings by the neoclassical artist John Flaxman was presented to UCL. There are over 10,000 pieces dating from the 15th century onwards including drawings by Turner, etchings by Rembrandt, and works by many leading 20th-century British artists. The works on paper are displayed in the Strang Print Room, which has limited regular opening times. The other works may be viewed by appointment.[233]

- Flaxman Gallery: a series of plaster casts of full-size details of sculptures by John Flaxman is located inside the Main Library under the central dome of the UCL Main Building.[234]

- Grant Museum of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy: a diverse Natural History collection covering the whole of the animal kingdom. Includes rare dodo and quagga skeletons. A teaching and research collection, it is named after Robert Edmund Grant, UCL's first professor of comparative anatomy and zoology from 1828, now mainly noted for having tutored the undergraduate Charles Robert Darwin at the University of Edinburgh in the 1826–1827 session.[235]

- Geology Collections: founded around 1855. Primarily a teaching resource and may be visited by appointment.[236]

- Institute of Archaeology Collections: items include prehistoric ceramics and stone artefacts from many parts of the world, the Petrie collection of Palestinian artefacts, and Classical Greek and Roman ceramics. Visits by appointment only.[237]

- Ethnography Collections: this collection exemplifying Material Culture holds an enormous variety of objects, textiles and artefacts from all over the world. Visits by appointment only.[238]

- Galton Collection: the scientific instruments, papers and personal memorabilia of Sir Francis Galton. Housed in the department of biology. Visits by appointment only.[239]

- Science Collections: diverse collections primarily accumulated in the course of UCL's own work, including the operating table on which the first anaesthetic was administered. Items may be a viewed by appointment.[240]

Rankings and reputation

| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2021)[241] | 10 |

| Guardian (2020)[242] | 22 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2020)[243] | 9 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2019)[244] | 15 |

| CWTS Leiden (2019)[245] | 18 |

| QS (2020)[246] | 8 |

| THE (2020)[247] | 15 |

| British Government assessment | |

| Teaching Excellence Framework[248] | Silver |

- International

In the 2021 QS World University Rankings, UCL is ranked 10th in the world, 2nd in London, 4th in the United Kingdom and 5th in Europe.[246] In the 2019/20 Rankings by Subject, UCL has 38 subjects in the world top 100. It is ranked in the world top 10 for nine subjects: anthropology (10th), archaeology (3rd), architecture (1st), anatomy and physiology (5th), education and training (1st), geography (7th), medicine (9th), pharmacy and pharmacology (7th), and psychology (10th). In broad subject areas, it is ranked 10th for life sciences and medicine, 15th for arts and humanities, 34th for social sciences and management, 49th for engineering and technology, and 63rd equal for natural sciences. In the QS Graduate Employability Ranking, UCL is ranked 22nd.[249]

In the 2019 Academic Ranking of World Universities, UCL is ranked 15th in the world (and 3rd in Europe).[244] In the 2016 subject tables it was ranked 8th in the world (and 2nd in Europe) for Clinical Medicine & Pharmacy,[250] joint 51st to 75th in the world (and joint 10th in Europe) for Engineering, Technology and Computer Sciences,[251] 9th in the world (and 2nd in Europe) for Life & Agricultural Sciences,[252] joint 51st to 75th in the world (and joint 14th in Europe) for Natural Sciences and Mathematics[253] and joint 51st to 75th in the world (and joint 12th in Europe) for Social Sciences.[254]

In the 2020 Times Higher Education World University Rankings, UCL is ranked 15th in the world (and 4th in Europe).[247] In the 2016/17 subject tables it was ranked 4th in the world (and 2nd in Europe) for Arts and Humanities,[255] 6th in the world (and 4th in Europe) for Clinical, Pre-Clinical and Health,[256] 12th in the world (and 6th in Europe) for Computer Science,[257] joint 38th in the world (and 12th in Europe) for Engineering and Technology,[258] 12th in the world (and 4th in Europe) for Life Sciences,[259] joint 23rd in the world (and 8th in Europe) for Physical Sciences[260] and 14th in the world (and 3rd in Europe) for Social Sciences.[261] In the 2017 Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings, UCL is ranked 16th in the world.[262] In the 2015 Times Higher Education Global Employability University Ranking, UCL is ranked 48th in the world.[263]

In 2019, UCL ranked 9th among the universities around the world by SCImago Institutions Rankings.[264] UCL is ranked 18th in the world (2nd in Europe) for number of publications and 18th in the world (6th in Europe) for quality of publications in the 2019 CWTS Leiden Ranking.[245] UCL is ranked 5th in the world (2nd in Europe) in the 2016/17 University Ranking by Academic Performance.[265] UCL is ranked 10th in the world (2nd in Europe) in the 2017 National Taiwan University Performance Ranking of Scientific Papers for World Universities.[266] UCL is also ranked 17th in the world (8th in Europe) in the 2017 Round University Ranking.[267] In the 2018 U.S. News & World Report Best Global University Ranking, UCL is ranked 22nd in the world (4th in Europe).[268]

- National

UCL is ranked as one of the top 10 multi-faculty universities in two of the three main UK university league tables. These place more emphasis on the undergraduate student experience than global rankings, using criteria such as teaching quality and learning resources, entry standards, employment prospects, research quality and dropout rates. In the 2019 Times Higher Education "Table of Tables", which is based on the combined results of the UK's three main domestic university rankings, UCL is ranked 10th.[269] Historically, in The Sunday Times 10-year (1998–2007) average ranking of British universities based on their league table performance, UCL was ranked 5th overall in the UK.[270] UCL was also one of only eight universities (along with the other members of the G5, Bath, St Andrews and Warwick) to have never been outside the top 15 in one of the three main domestic rankings between 2008–2017.[271]

In the 2021 Complete University Guide subject tables, UCL was ranked in the top 10 in 23 subjects out of 40 offered (57.5%).[272] In a 2015 Times Higher Education study UCL was chosen as the 8th best university in the UK for the quality of graduates according to recruiters from the UK's major companies.[273] According to data released by the Department for Education in 2018, UCL was rated as the 7th best university in the UK for boosting female graduate earnings with female graduates seeing a 15.5% increase in earnings compared to the average graduate, and the 10th best university for males, with male graduates seeing a 16.2% increase in earnings compared to the average graduate.[274]

Commercial activities

UCL has significant commercial activities and in 2014/15 these generated around £155 million in revenues.[2] UCL's principal commercial activities include UCL Business, UCL Consultants, and catering and accommodation services.[2] UCL has also participated in a number of commercial joint ventures, including EuroTempest Ltd and Imanova Ltd (now part of Invicro).[2]

UCL Business

UCL Business (UCLB) is a technology transfer company which is wholly owned by UCL. It has three main activities: licensing technologies, creating spin-out companies, and project management.[275] UCLB supports spin-out companies in areas including discovery disclosure, commercialisation, business plan development, contractual advice, incubation support, recruitment of management teams and identification of investors.[275] In the area of licensing technoloiges, UCLB provides commercial, legal and administrative advice to help companies broker licensing agreements.[275] UCLB also provides UCL departments and institutes with project management services for single or multi-party collaborative industry projects.[275]

UCLB had a turnover of £8 million in 2014/15 and as at 31 July 2015 had equity holdings in 61 companies.[276]

UCL Consultants

UCL Consultants (UCLC) is an academic consultancy services company which is wholly owned by UCL.[277] It provides four main service offerings: Academic Consultancy, Bespoke Short Courses, Testing & Analysis and Expert Witness.[278] As of 31 July 2018 UCLC had over 1,900 registered consultants.

UCLC had a turnover of £17.8 million in 2018/19.[279]

UCL Press

UCL Press is a university press wholly owned by UCL.[280] It was the first fully open access university press in the UK, and publishes monographs, textbooks and other academic books in a wide range of academic areas which are available to download for free, in addition to a number of journals[281] As of May 2018, UCL Press had had more than 1 million downloads of its open access books.[282]

Imanova

Imanova is a joint venture company of UCL, Imperial College London, Kings College London and the Medical Research Council which owns and manages the Clinical Imaging Centre located at Imperial College London's Hammersmith Hospital campus.[2]

Student life

Student body

In the 2014/15 academic year UCL had a total of 35,615 students, of whom 16,830 were undergraduate and 18,785 were postgraduate.[283] In that year, UCL had the third-largest total number of students of any university in the United Kingdom (after the Open University and the University of Manchester), and the largest number of postgraduate students.[283]

In 2013/14 87% of UCL's students were full-time and 13% part-time,[284] and 54% were female and 46% male.[285] In 2013/14, 12,330 UCL students were from outside the UK (43% of the total number of students in that year), of whom 5,504 were from Asia, 3,679 from the European Union ex. the United Kingdom, 1,195 from North America, 516 from the Middle East, 398 from Africa, 254 from Central and South America, and 166 from Australasia.[286]

As of 31 July 2015, UCL had around 220,000 alumni across 190 countries, of whom around 137,000 were based in the United Kingdom (and approximately 60,000 were based in London). The largest alumni communities outside of the UK are in the United States, Greece and China.[2]

Students' Union

Founded in 1893, Students' Union UCL, formerly the UCL Union, is one of the oldest students' unions in England, although postdating the Liverpool Guild of Students which formed a student representative council in 1892.[42][287] UCL Union operates both as the representative voice for UCL students, and as a provider of a wide range of services. It is democratically controlled through General Meetings and referendums, and is run by elected student officers. The Union has provided a prominent platform for political campaigning of all kinds in recent years. It also supports a range of services, including numerous clubs and societies, sports facilities, an advice service, and a number of bars, cafes and shops.[288] The union is also responsible for the organisation of a number of events, including, amongst others, the college's annual summer ball.

There are currently over 150 clubs and societies under the umbrella of the UCL Union, including: UCL Snowsports (one of the largest sports society at UCL, responsible for organising the annual UCL ski trip),[289] Pi Media (responsible for Pi Magazine and Pi Newspaper, UCL's official student publications);[290] UCL Union Debating Society, UCL's second oldest society (established 1829),[291] UCL Union Film Society, one of the country's oldest film societies with past members including Christopher Nolan;[292] and The Cheese Grater (a student magazine containing a mix of news investigations and humorous items).

Sport

The Union runs over 70 sports clubs,[293] including the UCL Cricket Club (Men's and Women's), UCL Boat Club (Men's and Women's clubs), UCL Running, Athletics and Cross Country Club (RAX), and UCL Rugby Club (Men's and Women's), as well as RUMS sports clubs, open for Medical students.

UCL clubs compete in inter-university fixtures in the British Universities and Colleges Sport (BUCS) competition in a range of sports, including athletics, basketball, cricket, fencing, football, hockey, netball, rugby union and tennis. In the 2014/15 season, UCL finished in 24th position in the final BUCS rankings of 151 participating higher education institutions.[294]

UCL sports facilities include a fitness centre at the main UCL campus in Bloomsbury, a sports centre in Somers Town and a 90-acre athletics ground in Shenley.[295]

Mascot

UCL mascot is Phineas Maclino, or Phineas, a wooden tobacconist's sign of a kilted Jacobite Highlander stolen from outside a shop in Tottenham Court Road during the celebrations of the relief of Ladysmith, part of the Second Boer War, in March 1900.[296] This establishment of mascots at both UCL and King's saw the beginning of mascotry, where Phineas would be kidnapped by King's and then this act would be avenged by UCL. In 1922, Phineas was briefly stolen by King's, and later during the 1927 rag the King's mascot 'Reggie the Lion' was captured by UCL students and his body filled with rotten apples. In 1993, the university's centenary year, Phineas was placed in the third floor bar of 25 Gordon Street and the bar named after him.[297]

Rivalry with King's College London

UCL has a long-running, mostly friendly rivalry with King's College London, which has historically been known as "Rags".[298] UCL students have been referred to by students from King's as the "Godless Scum of Gower Street", in reference to a comment made at the founding of King's, which was based on Christian principles. UCL students in turn referred to King's as "Strand Polytechnic".

The King's' mascot, Reggie the Lion, went missing in the 1990s and was recovered after being found dumped in a field. It was restored at the cost of around £15,000 and then placed on display in the students' union.[299] It is in a glass case and filled with concrete to prevent theft, particularly by UCL students who once castrated it. In turn, King's' students are also believed to have once stolen Phineas, a UCL mascot.[300] It is often claimed that King's' students played football with the embalmed head of Jeremy Bentham. Although the head was indeed stolen, the football story is a myth or legend which is unsupported by official UCL documentation about Bentham available next to his display case (his auto-icon) in the UCL cloisters. The head is now kept in the UCL vaults.[301]

Student campaigns

Student campaigns at UCL have included: UCLU Free Education Campaign (a campaign for the return of free and non-marketised higher education); the London Living wage Campaign (a campaign for a basic minimum wage for all UCL staff); Disarm UCL (a campaign which successfully persuaded UCL not to invest in defence companies); and Save UCL (this name has been used by two campaigns: one in 2006 which opposed a merger between UCL and Imperial College London in 2006, and a more recent one against education cuts).

As part of the protests against the UK Government's plans to increase student fees, around 200 students occupied the Jeremy Bentham Room and part of the Slade School of Fine Art for over two weeks during November and December 2010.[302][303] The university successfully obtained a court order to evict the students but stated that it did not intend to enforce the order if possible.[303]

Student campaigns around university run accommodation at UCL have gained momentum in recent years. In 2016, over 1000 students withholding rent and went on rent strike in protest of high rents and poor conditions. This rent strike was claimed by its organisers to have won over £1 million in rent cuts, freezes and grants from UCL.[304] Since 2016, there have been rent strikes in 2017, leading to UCL pledging around £1.4 million in bursaries and rent freezes, mostly in the form of bursaries for less well-off students which were set at £600,000 per year for the 2017/18 and 2018/19 academic years.[305] Another rent strike was held at two halls of residence in the third term of the 2017/18 academic year due to complaints over conditions at those Harris.[306]

Student housing

All first-year undergraduate students and overseas first-year postgraduates at UCL are guaranteed university accommodation.[307] The majority of second- and third-year undergraduate students and graduate students find their own accommodation in the private sector; graduate students and affiliate students may apply for accommodation but places are limited.

UCL students are eligible to apply for places in the University of London intercollegiate halls of residence.[308] The halls are: Canterbury Hall, Commonwealth Hall, College Hall, Connaught Hall, Hughes Parry Hall and International Hall near Russell Square in Bloomsbury; Lillian Penson Hall in Paddington; and Nutford House in Marble Arch. Some students are also selected to live in International Students House.

In 2013, a new student accommodation building on Caledonian Road was awarded the Carbuncle Cup and named the country's worst new building by Building Design magazine, with the comment "this is a building that the jury struggled to see as remotely fit for human occupation". Islington Council had originally turned down planning permission for the building, but this had been overturned on appeal.[309]

Notable people

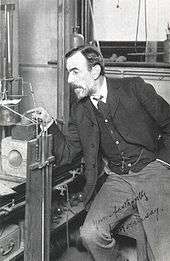

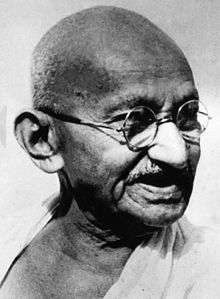

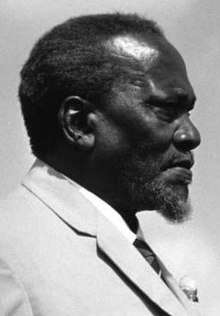

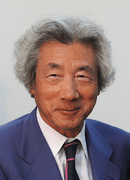

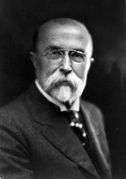

UCL alumni include Mahatma Gandhi (leader of the Indian independence moment and is considered the Father of the Nation of India), Alexander Graham Bell (inventor of the telephone), Francis Crick (co-discoverer of the structure of DNA), William Stanley Jevons (early pioneer of modern Economics), Jomo Kenyatta ("Father of the Nation" of Kenya), Kwame Nkrumah (founder of Ghana and "Father of African Nationalism") and Charles K. Kao ("Godfather of broadband"). Notable former staff include Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk ("Father of the Nation" of Czechoslovakia"), Peter Higgs (proposer of the Higgs mechanism which predicted the existence of the Higgs boson), Lucien Freud (artist) and Sir William Ramsay (discoverer of all of the naturally occurring noble gases).

Nobel Prizes have been awarded to at least 30 UCL academics and students (17 of which were in Physiology & Medicine), as well as three Fields Medals.[310][311]

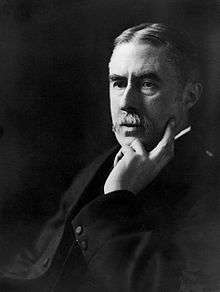

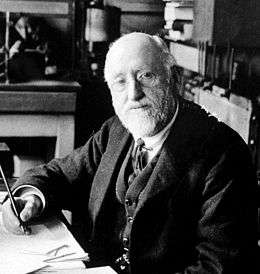

Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister.jpg)

.jpg)

Notable faculty and staff

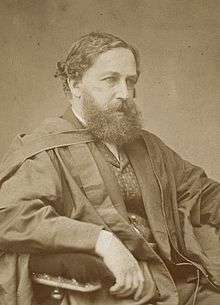

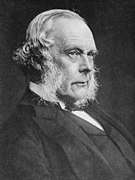

Notable former UCL faculty and staff include Jocelyn Bell Burnell (co-discoverer of radio pulsars), A. S. Byatt (writer), Ronald Dworkin (legal philosopher and scholar of constitutional law),[312] John Austin (legal philosopher, founder of analytical jurisprudence),[313] Sir A.J. Ayer (philosopher), Sir Ambrose Fleming (inventor of the first thermionic valve, the fundamental building block of electronics),[314] Lucian Freud (painter),[315] Andrew J Goldberg OBE (Chairman of Medical Futures),[316] Peter Higgs[317] (the proposer of the Higgs mechanism, which predicted the existence of the Higgs boson), Andrew Huxley (physiologist and biophysicist), William Stanley Jevons (economist), Sir Frank Kermode (literary critic), A. E. Housman (classical scholar, and poet), Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (first President of Czechoslovakia and "Father of the Nation"), John Stuart Mill (philosopher), Peter Kirstein CBE (computer scientist, significant role in the creation of the Internet), George R. Price (population geneticist), Edward Teller ("Father of the Hydrogen Bomb"), David Kemp (the first scientist to demonstrate the existence of the otoacoustic emissions)[318], Dadabhai Naoroji (Indian Parsi leader, the first Asian to be elected to UK House of Commons), Hannah Fry (data scientist, mathematician and BBC presenter) and Carl Gombrich (opera singer and university founder).

All five of the naturally occurring noble gases were discovered at UCL by Professor of Chemistry Sir William Ramsay, after whom Ramsay Hall is named.[319]

Hormones were first discovered at UCL by William Bayliss and Ernest Starling, the former also an alumnus of UCL.[320]

Notable alumni

Notable UCL alumni include:

- Artists including Dora Carrington (painter), Sir William Coldstream (realist painter), Wyndham Lewis (vorticist painter), Antony Gormley (sculptor), Augustus John (painter, draughtsman and etcher),[321] Gerry Judah (artist and designer), Ben Nicholson (abstract painter), Sir Eduardo Paolozzi (sculptor and artist), and Ibrahim el-Salahi (artist painter and former diplomat);

- Authors including Edith Clara Batho, Raymond Briggs,[322] Robert Browning, Amit Chaudhuri, G. K. Chesterton,[323] David Crystal, Stella Gibbons, Clive Sansom, Sean Thomas, Marie Stopes,[323] Helen MacInnes, Chioma Okereke, Rabindranath Tagore, Demetrius Vikelas (who was also the first President of the International Olympic Committee), and Marianne Winder;

- Business-oriented people including Colin Chapman (founder of Lotus Cars),[324] Demis Hassabis (co-founder and CEO of DeepMind), Lord Digby Jones (former Director-General of the Confederation of British Industry),[325] Rishi Khosla (serial entrepreneur, co-founder and CEO of fintech firm OakNorth Bank),[326] Edwin Waterhouse (founding partner of the professional services firm PwC), Dame Sharon White (Chairman of the John Lewis Partnership and former Chief Executive of Ofcom),[327] and billionaire Farhad Moshiri (Everton F.C. part owner);[328]