Cockney

The term Cockney is applied as a demonym to people from loosely defined areas of London; to East Enders[1][2][3] or to those born within the sound of Bow Bells.[4][5] The Cockney dialect is the form of speech used in those areas, and elsewhere, particularly among working class Londoners. In practice, these definitions are often blurred.

Within London, the Cockney dialect is, to an extent, being replaced by Multicultural London English, a new form of speech with significant Cockney influence. However, the migration of East Londoners to Essex, and elsewhere, has carried the dialect to new areas, sometimes in a blended form known Estuary English.[6][7][8]

Words and phrases

Etymology of Cockney

The earliest recorded use of the term is 1362 in passus VI of William Langland's Piers Plowman, where it is used to mean "a small, misshapen egg", from Middle English coken + ey ("a cock's egg").[9] Concurrently, the mythical land of luxury Cockaigne (attested from 1305) appeared under a variety of spellings, including Cockayne, Cocknay, and Cockney, and became humorously associated with the English capital London.[10][12]

The present meaning of cockney comes from its use among rural Englishmen (attested in 1520) as a pejorative term for effeminate town-dwellers,[14][9] from an earlier general sense (encountered in "The Reeve's Tale" of Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales c. 1386) of a "cokenay" as "a child tenderly brought up" and, by extension, "an effeminate fellow" or "a milksop".[15] This may have developed from the sources above or separately, alongside such terms as "cock" and "cocker" which both have the sense of "to make a nestle-cock ... or darling of", "to indulge or pamper".[17][18] By 1600, this meaning of cockney was being particularly associated with the Bow Bells area.[4][19] In 1617, the travel writer Fynes Moryson stated in his Itinerary that "Londoners, and all within the sound of Bow Bells, are in reproach called Cockneys."[20] The same year, John Minsheu included the term in this newly restricted sense in his dictionary Ductor in Linguas.[22]

Other terms

- Cockney sparrow: Refers to the archetype of a cheerful, talkative Cockney.

- Cockney diaspora: The term Cockney diaspora[23] refers to the migration of people from the East End to the home counties, especially Essex. It also refers to the descendants of those people, in areas where there was enough migration for an identification with the East End to persist in subsequent generations.

- Mockney: Refers to a fake cockney accent, though the term is sometimes also used as a self-deprecatory moniker, by second, third and subsequent generations of the cockney diaspora.

Region

Originally, when London consisted of little more than the walled City, the term applied to all Londoners, and this lingered into the 19th century.[10] As the city grew the definitions shifted to alternatives based on more specific geography, or of dialect. The terms “East End of London” and “within the sound of bow bells” are used interchangeably, and the bells are a symbol of East End identity. The area within earshot of the bells changes with the wind, but there is a correlation between the two geographic definitions under the typical prevailing wind conditions. The term is now used loosely to describe all East Londoners, irrespective of their speech.

London's East End

The traditional core districts of the East End include Bethnal Green, Whitechapel, Spitalfields, Stepney, Wapping, Limehouse, Poplar, Haggerston, Aldgate, Shoreditch, the Isle of Dogs, Hackney, Hoxton, Bow and Mile End. This area, north of the Thames, gradually expanded to include East Ham, Stratford, Leyton, West Ham and Plaistow as more land was built upon.

Bow Bells Audible Range

The church of St Mary-le-Bow is one of the oldest, largest and historically most important of the many churches in the City of London. The definition based on being born within earshot of the bells,[24] cast at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, reflects the early definition of the term as relating to all London.

The audible range of the Bells is dependent on geography and wind conditions. The east is mostly low lying, a factor which combines with the strength and regularity of the prevailing wind, blowing from west-south-west for nearly three quarters of the year,[25] to carry the sound further to the east, and more often. A 2012 study[26] showed that in the 19th century, and under typical conditions, the sound of the bells would carry as far as Clapton, Bow and Stratford in the east but only as far as Southwark to the south and Holborn in the west. An earlier study[27] suggested the sound would have carried even further. The 2012 study showed that in the modern era, noise pollution means that the bells can only be heard as far as Shoreditch. According to legend, Dick Whittington heard the bells 4.5 miles away at the Highgate Archway, in what is now north London. The studies mean that it is credible that Whittington might have heard them on one of the infrequent days that the wind blows from the south, .

The church of St Mary-le-Bow was destroyed in 1666 by the Great Fire of London and rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren. Although the bells were destroyed again in 1941 in the Blitz, they had fallen silent on 13 June 1940 as part of the British anti-invasion preparations of World War II. Before they were replaced in 1961, there was a period when, by the "within earshot" definition, no "Bow Bell" cockneys could be born.[28] The use of such a literal definition produces other problems, since the area around the church is no longer residential and the noise pollution means few are born within earshot.[29]

Based these definition of the bells audible range, all East Enders are cockneys, but not all cockneys are East Enders; though whereas an East Ender would be likely to proudly claim that entitlement, a resident of west, north or south London would be less likely to.

Dialect

Cockney speakers have a distinctive accent and dialect, and occasionally use rhyming slang. The Survey of English Dialects took a recording from a long-time resident of Hackney, and the BBC made another recording in 1999 which showed how the accent had changed.[30][31]

The early development of Cockney speech is obscure, but appears to have been heavily influenced by Essex and related eastern dialects,[32] while borrowings from Yiddish, including kosher (originally Hebrew, via Yiddish, meaning legitimate) and stumm (/ʃtʊm/ originally German, via Yiddish, meaning mute),[33] as well as Romani, for example wonga (meaning money, from the Romani "wanga" meaning coal),[34] and cushty (Kushty) (from the Romani kushtipen, meaning good) reflect the influence of those groups on the development of the speech.

John Camden Hotten, in his Slang Dictionary of 1859, makes reference to "their use of a peculiar slang language" when describing the costermongers of London's East End.

Migration and evolution

A dialectological study of Leytonstone in 1964 (then in Essex) found that the area's dialect was very similar to that recorded in Bethnal Green by Eva Sivertsen but there were still some features that distinguished Leytonstone speech from cockney.[35] "The Borough" to the south of Waterloo, London and Tower Bridges was a cockney speaking area, before redevelopment changed the working-class character of the neighbourhood, so that now, Bermondsey is the only cockney dialect area south of the River Thames.

Linguistic research conducted in the early 2010s suggests that today, certain elements of cockney English are declining in usage within the East End of London and the accent has migrated to Outer London and the Home Counties. In parts of London's East End, some traditional features of cockney have been displaced by a Jamaican Creole-influenced variety popular among young Londoners (sometimes referred to as "Jafaican"), particularly, though far from exclusively, those of Afro-Caribbean descent.[36] Nevertheless, the glottal stop, double negatives, and the vocalisation of the dark L (and other features of cockney speech) are among the Cockney influences on Multicultural London English, and some rhyming slang terms are still in common usage.

An influential July 2010 report by Paul Kerswill, Professor of Sociolinguistics at Lancaster University, Multicultural London English: the emergence, acquisition and diffusion of a new variety, predicted that the cockney accent will disappear from London's streets within 30 years.[36] The study, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, said that the accent, which has been around for more than 500 years, is being replaced in London by a new hybrid language. "Cockney in the East End is now transforming itself into Multicultural London English, a new, melting-pot mixture of all those people living here who learnt English as a second language", Prof Kerswill said.[36]

Conversely, the mostly post-war migration of cockney-speakers has led to a shift in the dialect area, towards the suburbs and Home Counties, especially Essex.[37][38] A series of new and expanded towns have often had a strong influence on local speech. Many areas beyond the capital have become Cockney-speaking to a greater or lesser degree, including the new towns of Basildon and Harlow, and expanded towns such as Grays, Chelmsford and Southend. However, this is, except where least mixed, difficult to discern because of common features: linguistic historian and researcher of early dialects Alexander John Ellis in 1890 stated that cockney developed owing to the influence of Essex dialect on London speech.[32]

Writing in 1981, the dialectologist Peter Wright identified the building of the Becontree estate near Dagenham in Essex as influential in the spread of cockney dialect. This very large estate was built by the Corporation of London to house poor East Enders in a previously rural area of Essex. The residents typically kept their cockney dialect rather than adopt an Essex dialect.[39] Wright also reports that cockney dialect spread along the main railway routes to towns in the surrounding counties as early as 1923, spreading further after World War II when many refugees left London owing to the bombing, and continuing to speak cockney in their new homes.[40]

A more distant example where the accent stands out is Thetford in Norfolk, which tripled in size from 1957 in a deliberate attempt to attract Londoners by providing social housing funded by the London County Council.[41]

Typical features

- As with many accents of the United Kingdom, cockney is non-rhotic. A final -er is pronounced [ə] or lowered [ɐ] in broad cockney. As with all or nearly all non-rhotic accents, the paired lexical sets COMMA and LETTER, PALM/BATH and START, THOUGHT and NORTH/FORCE, are merged. Thus, the last syllable of words such as cheetah can be pronounced [ɐ] as well in broad cockney.[42][43][44]

- Broad /ɑː/ is used in words such as bath, path, demand. This originated in London in the 16th–17th centuries and is also part of Received Pronunciation (RP).[45]

- T-glottalisation: use of the glottal stop as an allophone of /t/ in various positions,[46][47] including after a stressed syllable. Glottal stops also occur, albeit less frequently for /k/ and /p/, and occasionally for mid-word consonants. For example, Richard Whiteing spelt "Hyde Park" as Hy′ Par′. Like and light can be homophones. "Clapham" can be said as Cla'am (i. e., [ˈkl̥ɛʔm̩]).[45] /t/ may also be flapped intervocalically, e.g. utter [ˈɐɾə]. London /p, t, k/ are often aspirated in intervocalic and final environments, e.g., upper [ˈɐpʰə], utter [ˈɐtʰə], rocker [ˈɹɒkʰə], up [ɐʔpʰ], out [æə̯ʔtʰ], rock [ɹɒʔkʰ], where RP is traditionally described as having the unaspirated variants. Also, in broad cockney at least, the degree of aspiration is typically greater than in RP, and may often also involve some degree of affrication [pᶲʰ, tˢʰ, kˣʰ]. Affricatives may be encountered in initial, intervocalic, and final position.[48][49]

- This feature results in cockney being often mentioned in textbooks about Semitic languages while explaining how to pronounce the glottal stop.

- Th-fronting:[50]

- Yod-coalescence in words such as tune [tʃʰʉːn] or reduce [ɹɪˈdʒʉːs] (compare traditional RP [ˈtjuːn, ɹɪˈdjuːs]).[53]

- The alveolar stops /t/, /d/ are often omitted in informal cockney, in non-prevocalic environments, including some that cannot be omitted in Received Pronunciation. Examples include [ˈdæzɡənə] Dad's gonna and [ˈtɜːn ˈlef] turn left.[54]

- H-dropping. Sivertsen considers that [h] is to some extent a stylistic marker of emphasis in cockney.[55][56]

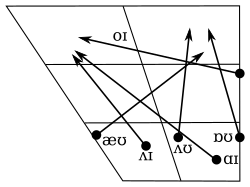

- Diphthong alterations:[57]

- /iː/ → [əi~ɐi]:[58][59] [bəiʔ] "beet"

- /eɪ/ → [æɪ~aɪ]:[60] [bæɪʔ] "bait"

- /aɪ/ → [ɑɪ] or even [ɒɪ] in "vigorous, dialectal" cockney. The second element may be reduced or absent (with compensatory lengthening of the first element), so that there are variants such as [ɑ̟ə~ɑ̟ː]. This means that pairs such as laugh-life, Barton-biting may become homophones: [lɑːf], [bɑːʔn̩]. But this neutralisation is an optional, recoverable one:[61] [bɑɪʔ] "bite"

- /ɔɪ/ → [ɔ̝ɪ~oɪ]:[61] [ˈtʃʰoɪs] "choice"

- /uː/ → [əʉ] or a monophthongal [ʉː], perhaps with little lip rounding, [ɨː] or [ʊː]:[58][62] [bʉːʔ] "boot"

- /əʊ/ → this diphthong typically starts in the area of the London /ʌ/, [æ̈~ɐ]. The endpoint may be [ʊ], but more commonly it is rather opener and/or completely unrounded, i.e. [ɤ̈] or [ɤ̝̈]. Thus, the most common variants are [æ̈ɤ̈, æ̈ɤ̝̈, ɐɤ̈] and [ɐɤ̝̈], with [æ̈ʊ] and [ɐʊ] also being possible. The broadest cockney variant approaches [aʊ]. There's also a variant that is used only by women, namely [ɐø ~ œ̈ø]. In addition, there are two monophthongal pronunciations, [ʌ̈ː] as in 'no, nah' and [œ̈], which is used in non-prominent variants.[63] [kʰɐɤ̈ʔ] "coat"

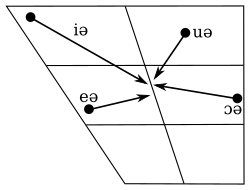

- /ɪə/ and /eə/ have somewhat tenser onsets than in RP: [iə], [ɛ̝ə][44][64]

- /ʊə/, according to Wells (1982), is being increasingly merged with /ɔː/ ~ /ɔə/.[44]

- /aʊ/ may be [æʊ][64] or [æə].[65]

- /ɪə/, /eə/, /ʊə/, /ɔə/ and /aʊ/ can be monophthongised to [ɪː], [ɛː], [ʊː] (if it doesn't merge with /ɔː/ ~ /ɔə/), [ɔː] and [æː] ~ [aː].[65] Wells (1982) states that "no rigid rules can be given for the distribution of monophthongal and diphthongal variants, though the tendency seems to be for the monophthongal variants to be commonest within the utterance, but the diphthongal realisations in utterance-final position, or where the syllable in question is otherwise prominent."[66]

- Disyllabic [ɪi.ə, ɛi.ə, ɔu.ə, æi.ə] realizations of /iə, eə, ɔə, æʊ/ are also possible, and are regarded as "very strongly Cockney".[67] Among these, the triphthongal realization of /ɔə/ occurs most commonly.[68] There is not a complete agreement about the distribution of these; according to Wells (1982), they "occur in sentence-final position",[59] whereas according to Mott (2012), these are "most common in final position".[68]

- Other vowel differences include

- /æ/ may be [ɛ] or [ɛɪ], with the latter occurring before voiced consonants, particularly before /d/:[44][69] [bɛk] "back", [bɛːɪd] "bad"

- /ɛ/ may be [eə], [eɪ], or [ɛɪ] before certain voiced consonants, particularly before /d/:[44][70][71][72] [beɪd] "bed"

- /ɒ/ may be a somewhat less open [ɔ]:[44] [kʰɔʔ] "cot"

- /ɑː/ has a fully back variant, qualitatively equivalent to cardinal 5, which Beaken (1971) claims characterises "vigorous, informal" cockney.[44]

- /ɜː/ is on occasion somewhat fronted and/or lightly rounded, giving cockney variants such as [ɜ̟ː], [œ̈ː].[44]

- /ʌ/ → [ɐ̟] or a quality like that of cardinal 4, [a]:[44][69] [dʒamʔˈtˢapʰ] "jumped up"

- /ɔː/ → [oː] or a closing diphthong of the type [oʊ~ɔo] when in non-final position, with the latter variants being more common in broad cockney:[73][74] [soʊs] "sauce"-"source", [loʊd] "lord", [ˈwoʊʔə] "water"

- /ɔː/ → [ɔː] or a centring diphthong/triphthong of the type [ɔə~ɔuə] when in final position, with the latter variants being more common in broad cockney; thus [sɔə] "saw"-"sore"-"soar", [lɔə] "law"-"lore", [wɔə] "war"-"wore". The diphthong is retained before inflectional endings, so that board and pause can contrast with bored [bɔəd] and paws [pʰɔəz].[74] /ɔə/ has a somewhat tenser onset than the cardinal /ɔ/, that is [ɔ̝ə].[64]

- /əʊ/ becomes something around [ɒʊ~ɔo] or even [aɤ] in broad cockney before dark l. These variants are retained when the addition of a suffix turns the dark l clear. Thus a phonemic split has occurred in London English, exemplified by the minimal pair wholly [ˈhɒʊli] vs. holy [ˈhɐɤ̈li]. The development of L-vocalisation (see next section) leads to further pairs such as sole-soul [sɒʊ] vs. so-sew [sɐɤ̈], bowl [bɒʊ] vs. Bow [bɐɤ̈], shoulder [ˈʃɒʊdə] vs. odour [ˈɐɤ̈də], while associated vowel neutralisations may make doll a homophone of dole, compare dough [dɐɤ̈]. All this reinforces the phonemic nature of the opposition and increases its functional load. It is now well-established in all kinds of London-flavoured accents, from broad cockney to near-RP.[75]

- /ʊ/ in some words (particularly good)[76] is central [ʊ̈].[77] In other cases, it is near-close near-back [ʊ], as in traditional RP.[77]

- Vocalisation of dark L, hence [ˈmɪowɔː] for Millwall. The actual realisation of a vocalised /l/ is influenced by surrounding vowels and it may be realised as [u], [ʊ], [o] or [ɤ]. It is also transcribed as a semivowel [w] by some linguists, e.g., Coggle and Rosewarne.[78] However, according to Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996), the vocalised dark l is sometimes an unoccluded lateral approximant, which differs from the RP [ɫ] only by the lack of the alveolar contact.[79] Relatedly, there are many possible vowel neutralisations and absorptions in the context of a following dark L ([ɫ]) or its vocalised version; these include:[80]

- In broad cockney, and to some extent in general popular London speech, a vocalised /l/ is entirely absorbed by a preceding /ɔː/: e.g., salt and sort become homophones (although the contemporary pronunciation of salt /sɒlt/[81] would prevent this from happening), and likewise fault-fought-fort, pause-Paul's, Morden-Malden, water-Walter. Sometimes such pairs are kept apart, in more deliberate speech at least, by a kind of length difference: [ˈmɔʊdn̩] Morden vs. [ˈmɔʊːdn̩] Malden.

- A preceding /ə/ is also fully absorbed into vocalised /l/. The reflexes of earlier /əl/ and earlier /ɔː(l)/ are thus phonetically similar or identical; speakers are usually ready to treat them as the same phoneme. Thus awful can best be regarded as containing two occurrences of the same vowel, /ˈɔːfɔː/. The difference between musical and music-hall, in an H-dropping broad cockney, is thus nothing more than a matter of stress and perhaps syllable boundaries.

- With the remaining vowels a vocalised /l/ is not absorbed, but remains phonetically present as a back vocoid in such a way that /Vl/ and /V/ are kept distinct.

- The clearest and best-established neutralisations are those of /ɪ~iː~ɪə/ and /ʊ~uː~ʊə/. Thus rill, reel and real fall together in cockney as [ɹɪɤ]; while full and fool are [foʊ~fʊu] and may rhyme with cruel [ˈkʰɹʊu]. Before clear (i.e., prevocalic) /l/ the neutralisations do not usually apply, thus [ˈsɪli] silly but [ˈsɪilɪn] ceiling-sealing, [ˈfʊli] fully but [ˈfʊulɪn] fooling.

- In some broader types of cockney, the neutralisation of /ʊ~uː~ʊə/ before non-prevocalic /l/ may also involve /ɔː/, so that fall becomes homophonous with full and fool [fɔo].

- The other pre-/l/ neutralisation which all investigators agree on is that of /æ~eɪ~aʊ/. Thus, Sal and sale can be merged as [sæɤ], fail and fowl as [fæɤ], and Val, vale-veil and vowel as [væɤ]. The typical pronunciation of railway is [ˈɹæʊwæɪ].

- According to Siversten, /ɑː/ and /aɪ/ can also join in this neutralisation. They may on the one hand neutralise with respect to one another, so that snarl and smile rhyme, both ending [-ɑɤ], and Child's Hill is in danger of being mistaken for Charles Hill; or they may go further into a fivefold neutralisation with the one just mentioned, so that pal, pale, foul, snarl and pile all end in [-æɤ]. But these developments are evidently restricted to broad cockney, not being found in London speech in general.

- A neutralisation discussed by Beaken (1971) and Bowyer (1973), but ignored by Siversten (1960), is that of /ɒ~əʊ~ʌ/. It leads to the possibility of doll, dole and dull becoming homophonous as [dɒʊ] or [da̠ɤ]. Wells' impression is that the doll-dole neutralisation is rather widespread in London, but that involving dull less so.

- One further possible neutralisation in the environment of a following non-prevocalic /l/ is that of /ɛ/ and /ɜː/, so that well and whirl become homophonous as [wɛʊ].

- Cockney has been occasionally described as replacing /ɹ/ with /w/. For example, thwee (or fwee) instead of three, fwasty instead of frosty. Peter Wright, a Survey of English Dialects fieldworker, concluded that this was not a universal feature of cockneys but that it was more common to hear this in the London area than anywhere else in Britain.[82] This description may also be a result of mishearing the labiodental R as /w/, when it is still a distinct phoneme in cockney.

- An unstressed final -ow may be pronounced [ə]. In broad cockney this can be lowered to [ɐ].[43][44] This is common to most traditional, Southern English dialects except for those in the West Country.[83]

- Grammatical features:[55]

- Use of me instead of my, for example, "At's me book you got 'ere". It cannot be used when "my" is emphasised; e.g., "At's my book you got 'ere" (and not "their").

- Use of ain't

- Use of double negatives, for example "I didn't see nuffink".[84]

By the 1980s and 1990s, most of the features mentioned above had partly spread into more general south-eastern speech, giving the accent called Estuary English; an Estuary speaker will use some but not all of the cockney sounds.[85][86][87]

Perception

The cockney accent has long been looked down upon and thought of as inferior by many. For example, in 1909 the Conference on the Teaching of English in London Elementary Schools issued by the London County Council, stating that "the Cockney mode of speech, with its unpleasant twang, is a modern corruption without legitimate credentials, and is unworthy of being the speech of any person in the capital city of the Empire".[88] Others defended the language variety: "The London dialect is really, especially on the South side of the Thames, a perfectly legitimate and responsible child of the old kentish tongue [...] the dialect of London North of the Thames has been shown to be one of the many varieties of the Midland or Mercian dialect, flavoured by the East Anglian variety of the same speech".[88] Since then, the cockney accent has been more accepted as an alternative form of the English language rather than an inferior one. In the 1950s, the only accent to be heard on the BBC (except in entertainment programmes such as The Sooty Show) was RP, whereas nowadays many different accents, including cockney or accents heavily influenced by it, can be heard on the BBC.[89] In a survey of 2,000 people conducted by Coolbrands in the autumn of 2008, cockney was voted equal fourth coolest accent in Britain with 7% of the votes, while The Queen's English was considered the coolest, with 20% of the votes.[90] Brummie was voted least popular, receiving just 2%. The cockney accent often featured in films produced by Ealing Studios and was frequently portrayed as the typical British accent in movies by Walt Disney.

Spread

Studies have indicated that the heavy use of South East England accents on television and radio may be the cause of the spread of cockney English since the 1960s.[91][92][93][94] Cockney is more and more influential and some claim that in the future many features of the accent may become standard.[95]

Scotland

Studies have indicated that working-class adolescents in areas such as Glasgow have begun to use certain aspects of cockney and other Anglicisms in their speech.[96] infiltrating the traditional Glasgow patter.[97] For example, TH-fronting is commonly found, and typical Scottish features such as the postvocalic /r/ are reduced.[98] Research suggests the use of English speech characteristics is likely to be a result of the influence of London and South East England accents featuring heavily on television, such as the popular BBC One soap opera Eastenders.[91][92][93][94] However, such claims have been criticised.[99]

England

Certain features of cockney – Th-fronting, L-vocalisation, T-glottalisation, and the fronting of the GOAT and GOOSE vowels – have spread across the south-east of England and, to a lesser extent, to other areas of Britain.[100] However, Clive Upton has noted that these features have occurred independently in some other dialects, such as TH-fronting in Yorkshire and L-vocalisation in parts of Scotland.[101]

The term Estuary English has been used to describe London pronunciations that are slightly closer to RP than cockney. The variety first came to public prominence in an article by David Rosewarne in the Times Educational Supplement in October 1984.[102] Rosewarne argued that it may eventually replace Received Pronunciation in the south-east. The phonetician John C. Wells collected media references to Estuary English on a website. Writing in April 2013, Wells argued that research by Joanna Przedlacka "demolished the claim that EE was a single entity sweeping the southeast. Rather, we have various sound changes emanating from working-class London speech, each spreading independently".[103]

Pearly Tradition

The Pearly Kings and Queens are famous as an East End institution, but that perception is not wholly correct as they are found in other places across London, including Peckham and Penge in south London.

Notable cockneys

- Danny Baker, broadcaster, born in Deptford

- Michael Caine, actor, born as Maurice Joseph Micklewhite, Jr., 14 March 1933, in Rotherhithe[104]

- Albert Chevalier, famous Victorian music hall singer, born as Albert Onésime Britannicus Gwathveoyd Louis Chevalier in Royal Crescent, London, 21 March 1861

- Alfie Bass, actor from Bethnal Green

- Charlie Chaplin, comic actor, filmmaker, and composer, 16 April 1889, born in Walworth, London

- Roger Daltrey, singer, actor and vocalist of The Who, 1 March 1944, born in East Acton, London

- Alan Ford, actor, born in Walworth

- Samantha Fox, pop singer and glamour model, born in Mile End

- Steve Harley, musician, frontman of the band Cockney Rebel, born in Deptford

- Hoxton Tom McCourt, musician, face, born in Shoreditch and lived in Hoxton

- Lenny McLean, bare knuckle/unlicensed boxer, actor, born in Hoxton

- Claude Rains, the actor born in Camberwell in 1889 became famous after abandoning his heavy cockney accent and developing a unique Mid-Atlantic accent described as "half American, half English and a little Cockney thrown in"

- Harry Redknapp, former footballer and manager, born in Poplar

- Tommy Steele, 1950s pop and film artist, born in Bermondsey

- Kray twins, criminals, born in Hoxton and lived in Bethnal Green

- Barbara Windsor, actress, born in Shoreditch, London

- Ray Winstone, actor, born in Homerton[105]

- Arthur Smith, comedian from Bermondsey

- Micky Flanagan, comedian from Whitechapel

- Eric Bristow, darts champion born in Hackney, nicknamed the "Crafty Cockney" while playing in an American bar with that name

- Roger Bisby, journalist, born in City of London

- Len Goodman, ballroom dancer and television personality from Bethnal Green

- Derek Jameson, journalist and broadcaster from Hackney

- Terry Naylor, former footballer, born in Islington

- Martin Kemp, musician, born in Islington

- Gary Kemp, musician, born in Smithfield

- Mark Strong, actor, born in Clerkenwell

- Mike Reid, actor and comedian from Hackney

- Danny Dyer, actor from Custom House

Writing in 1981, the dialectologist Peter Wright gave some examples of then-contemporary Cockney speakers:[106]

- Harry Champion, music-hall singer and comedian

- Henry Cooper, boxer

- Jack Dash, trade unionist

- Warren Mitchell, known for playing Alf Garnett in Till Death Us Do Part. Wright wrote that "the dialect is quite genuine" in the series.[106]

A band called the Cockney Rejects are credited with creating a sub-genre of punk rock called Oi!, which gained its name from the use of Cockney dialect in the songs.[107]

Use in films

- Many of Ken Loach's early films were set in London. Loach has a reputation for using genuine dialect speakers in films:

- 3 Clear Sundays

- Up the Junction

- Cathy Come Home

- Poor Cow (the title being a cockney expression for "poor woman")

- Alfie

- Sparrows Can't Sing. The film had to be subtitled when released in the United States owing to difficulties with audience comprehension.[108]

- Bronco Bullfrog. The film's tagline was "Cockney youth - with English subtitles".[109]

- The Long Good Friday. The DVD of this film has an extra feature that explains the rhyming slang used.

- My Fair Lady

- In A Clockwork Orange, the fictional language used of Nadsat had some influence from cockney.

- Mary Poppins (and featuring Dick Van Dyke's infamous approximation of a Cockney accent)

- Mary Poppins Returns (with Lin Manuel Miranda, who plays Jack, stating "If they [the audience] didn't like Dick's accent, they'll be furious with mine")

- Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007) — Mrs Nellie Lovett and Tobias Ragg have Cockney accents.

- Passport to Pimlico. A newspaper headline in the film refers to the Pimlico residents as "crushed cockneys".

- Cockneys vs Zombies

- My Little Pony: Equestria Girls – Spring Breakdown. Ragamuffin, portrayed by Jason Michas, has a Cockney accent.

- Pinocchio (1940), The Coachman, voiced by Charles Judels, has a cockney accent

- The Gentlemen

- Harry Potter Series. Villians tend to have Cockney accents.

See also

References

- Green, Jonathon "Cockney". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- Miller, Marjorie (July 8, 2001). "Say what? London's cockney culture looks a bit different". Chicago Tribune.

- Oakley, Malcolm (30 September 2013). "History of The East London Cockney". East London History.

- "Born within the sound of Bow Bells". Phrases.org.uk. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 627.

- "Estuary English Q and A - JCW". Phon.ucl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- Roach, Peter (2009). English Phonetics and Phonology. Cambridge. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-71740-3.

- Trudgill, Peter (1999), The Dialects of England (2nd ed.), p. 80, ISBN 0-631-21815-7

- Oxford English Dictionary (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- Hotten, John Camden (1859). "Cockney". A Dictionary of Modern Slang, Cant, and Vulgar Words. p. 22. Cockney: a native of London. An ancient nickname implying effeminacy, used by the oldest English writers, and derived from the imaginary fool's paradise, or lubberland, Cockaygne.

- Oxford English Dictionary (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. 2009.

- Note, however, that the earliest attestation of this particular usage provided by the Oxford English Dictionary is from 1824 and consists of a tongue-in-cheek allusion to an existing notion of "Cockneydom".[11]

- Whittington, Robert. Vulgaria. 1520.

- "This cokneys and tytyllynges ... [delicati pueri] may abide no sorrow when they come to age ... In this great cytees as London, York, Perusy and such ... the children be so nycely and wantonly brought up ... that commonly they can little good.[13]

- Cumberledge, Geoffrey. F. N. Robinson (ed.). The Poetical Works of Geoffrey Chaucer. Oxford University Press. p. 70 & 1063.

- Locke, John (1695). Some thoughts concerning education (Third ed.). p. 7.

- "... I shall explain myself more particularly; only laying down this as a general and certain observation for the women to consider, viz. that most children's constitutions are spoiled, or at least harmed, by cockering and tenderness."[16]

- Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. "cocker, v.1" & "cock, v.6". Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1891

- Rowlands, Samuel. The Letting of Humours Blood in the Head-Vaine. 1600.

- "Bow Bells". London.lovesguide.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "A Cockney or a Cocksie, applied only to one born within the sound of Bow bell, that is in the City of London". Note, however, that his proffered etymology — from either "cock" and "neigh" or from the Latin incoctus — were both erroneous.[21] The humorous folk etymology which grew up around the derivation from "cock" and "neigh" was preserved by Francis Grose's 1785 [http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/5402 A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue

- Academic paper on speech changes in the Cockney diaspora https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/98762773/The_PRICE_MOUTH_crossover_in_the_Cockney_Diaspora_Cole_Strycharczuk.pdf

- "St Mary-le-Bow". www.stmarylebow.co.uk.

- Prevailing wind al LHR https://www.heathrow.com/content/dam/heathrow/web/common/documents/company/local-community/noise/reports-and-statistics/reports/community-noise-reports/CIR_Ascot_0914_0215.pdf

- By 24 Acoustics for the Times Atlas of London https://www.standard.co.uk/news/london/bow-bells-to-be-given-audio-boost-to-curb-decline-of-cockneys-7880794.html

- In 2000for the City of London - unable to find the details anywhere, but it said the bells would have been heard up to six miles to the east, five miles to the north, three miles to the south, and four miles to the west. http://public.oed.com/aspects-of-english/english-in-use/cockney/

- J. Swinnerton, The London Companion (Robson, 2004), p. 21.

- Wright (1981), p. 11.

- British Library (10 March 2009). "Survey of English Dialects, Hackney, London". Sounds.bl.uk. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- British Library (10 March 2009). "British Library Archival Sound Recordings". Sounds.bl.uk. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- Ellis (1890), pp. 35, 57, 58.

- "Definition of shtumm". Allwords.com. 14 September 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- "money slang history, words, expressions and money slang meanings, london cockney money slang words meanings expressions". Businessballs.com. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Werth, P.N. (1965). The Dialect of Leytonstone, East London (Bachelor). University of Leeds. p. 16.

- "Cockney to disappear from London 'within 30 years'". bbc.co.uk. 1 July 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- Alwakeel, Ramzy. "Forget Tower Hamlets - Romford is new East End, says Cockney language study".

- Brooke, Mike. "Cockney dialect migrated to Essex, Dr Fox tells East End Cockney Festival".

- Wright (1981), p. 146.

- Wright (1981), p. 147.

- The Cockneys of Thetford, The Economist, 21 December 2019

- Wright (1981), pp. 133–135.

- "Cockney English". Ic.arizona.edu. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- Wells (1982), p. 305.

- Wright (1981), pp. 136–137.

- Sivertsen (1960), p. 111.

- Hughes & Trudgill (1979), pp. 34.

- Sivertsen (1960), p. 109.

- Wells (1982), p. 323.

- Sivertsen (1960), p. 124.

- Wright (1981), p. 137.

- Wells (1982), p. 329.

- "Cockney accent - main features". rogalinski.com.pl – Journalist blog. 31 July 2011. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Wells (1982), p. 327.

- Robert Beard. "Linguistics 110 Linguistic Analysis: Sentences & Dialects, Lecture Number Twenty One: Regional English Dialects English Dialects of the World". Departments.bucknell.edu. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- Wells (1982:322)

- Hughes & Trudgill (1979), pp. 39–41.

- Matthews (1938), p. 78.

- Wells (1982), p. 306.

- Wells (1982), pp. 307–308.

- Wells (1982), pp. 308, 310.

- Wells (1982), pp. 306–307.

- Wells (1982), pp. 308–310.

- Mott (2012), p. 77.

- Wells (1982), pp. 305, 309.

- Wells (1982), pp. 305–306.

- Wells (1982), pp. 306, 310.

- Mott (2012), p. 78.

- Hughes & Trudgill (1979), p. 35.

- Sivertsen (1960), p. 54.

- Wells (1982), p. 129.

- Cruttenden (2001), p. 110.

- Matthews (1938), p. 35.

- Wells (1982), pp. 310–311.

- Wells (1982), pp. 312–313.

- Mott (2011), p. 75.

- Mott (2012), p. 75.

- Sivertsen (1960), p. 132.

- Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996), p. 193.

- Wells (1982), pp. 313–317.

- "Phonological change in spoken English". Bl.uk. 12 March 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- Wright (1981), p. 135.

- Wright (1981), p. 134.

- Wright (1981), p. 122.

- "Rosewarne, David (1984). "Estuary English". Times Educational Supplement, 19 (October 1984)". Phon.ucl.ac.uk. 21 May 1999. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "Wells, John (1994). "Transcribing Estuary English - a discussion document". Speech Hearing and Language: UCL Work in Progress, volume 8, 1994, pp. 259–67". Phon.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "Altendorf, Ulrike (1999). "Estuary English: is English going Cockney?" In: Moderna Språk, XCIII, 1, 1–11" (PDF). Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "5" (PDF). Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "BBC English". BBC English. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- Irvine, Chris (September 2008). "RP still most popular accent". London: telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- "Soaps may be washing out accent - BBC Scotland". BBC News. 4 March 2004. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "We fink, so we are from Glasgow". Timesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ""Scots kids rabbitin' like Cockneys" - "Sunday Herald"". Findarticles.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- Archived 30 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Rogaliński, Paweł (2011). British Accents: Cockney, RP, Estuary English. p. 15.

- Is TV a contributory factor in accent change in adolescents? – ESRC Society Today

- "Cockney creep puts paid to the patter – "Evening Times"". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. 4 March 2004. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- Stuart-Smith, Jane; Timmins, Claire; Tweedie, Fiona (17 April 2007). "'Talkin' Jockney'? Variation and change in Glaswegian accent". Journal of Sociolinguistics. 11 (2): 221–260. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2007.00319.x. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- A Handbook of Varieties of English, Volume 1, p. 185.

- "Joanna Przedlacka, 2002. Estuary English? Frankfurt: Peter Lang" (PDF).

- Upton, Clive (2012). "Modern Regional English in the British Isles". In Mugglestone, Lynda (ed.). The Oxford History of English. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 395.

- "Rosewarne, David (1984). "Estuary English". Times Educational Supplement, 19 (October 1984)". Phon.ucl.ac.uk. 21 May 1999. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- Wells, John (17 April 2013). "estuariality". Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- "Screening Room Special: Michael Caine" (29 October 2007). CNN. 25 June 2015.

- "Ray Winstone: Me cockney accent won the role". WhatsonTV (13 November 2016). Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Wright (1981), p. 23.

- The Subcultures Network (10 March 2017). Fight Back: Punk, Politics and Resistance. Oxford University Press. p. 39.

- "Stephen Lewis, actor - obituary". Daily Telegraph. London. 13 August 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- "IMDB - Bronco Bullfrog (1970) - Taglines". Retrieved 20 July 2019.

Bibliography

- Cruttenden, A. (2001). Gimson's Pronunciation of English (6th ed.). London: Arnold.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ellis, Alexander J. (1890). English dialects: Their Sounds and Homes.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hughes, Arthur; Trudgill, Peter (1979). English Accents and Dialects: An Introduction to Social and Regional Varieties of British English. Baltimore: University Park Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4.

- Matthews, William (1938). Cockney, Past and Present: a Short History of the Dialect of London. Detroit: Gale Research Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mott, Brian (2012), "Traditional Cockney and popular London speech", Dialectologia, RACO (Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert), 9: 69–94, ISSN 2013-2247CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rogaliński, Paweł (2011). British Accents: Cockney, RP, Estuary English. Łódź. ISBN 978-83-272-3282-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sivertsen, Eva (1960). Cockney Phonology. Oslo: University of Oslo.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Volume 1: An Introduction (pp. i–xx, 1–278), Volume 2: The British Isles (pp. i–xx, 279–466). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-52129719-2, 0-52128540-2.

- Wright, Peter (1981). Cockney Dialect and Slang. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Grose's 1811 dictionary

- Whoohoo Cockney Rhyming Slang translator

- Money slang expressions

- Sounds Familiar? — Listen to examples of London and other regional accents and dialects of the UK on the British Library's "Sounds Familiar" website