Stamford Bridge (stadium)

Stamford Bridge (/ˈstæmfərd/) is a football stadium in Fulham, adjacent to the borough of Chelsea in South West London, commonly referred to as The Bridge.[5][6] It is the home of Chelsea Football Club, which competes in the Premier League, the highest division of English football.

"The Bridge" | |

Stamford Bridge in 2013 | |

%26groups%3D_43c551253f3b40c9b48aa4acf477c22670ed79f7.svg)

| |

| Full name | Stamford Bridge |

|---|---|

| Location | Fulham London, SW6 England |

| Coordinates | 51°28′54″N 0°11′28″W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | Chelsea Pitch Owners plc |

| Operator | Chelsea F.C. |

| Executive suites | 51 |

| Capacity | 40,834[1] |

| Record attendance | 82,905 (Chelsea–Arsenal, 12 October 1935)[2] |

| Field size | 103 by 67.5 metres (112.6 yd × 73.8 yd) |

| Surface | GrassMaster by Tarkett Sports[3] |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1876 |

| Opened | 28 April 1877[4] |

| Renovated | 1904–1905, 1998 |

| Architect | Archibald Leitch (1887) |

| Tenants | |

| London Athletic Club (1877–1904) Chelsea (1905–present) London Monarchs (NFL Europe) (1997) | |

The capacity of the stadium is 40,834,[1] making it the ninth largest venue of the 2019–20 Premier League season. The club had plans to expand capacity to 63,000 by the 2023–24 season.[7]

Opened in 1877, the stadium was used by the London Athletic Club until 1905, when new owner Gus Mears founded Chelsea Football Club to occupy the ground; Chelsea have played their home games there ever since. It has undergone major changes over the years, most recently in the 1990s when it was renovated into a modern, all-seater stadium.

Stamford Bridge has been a venue for England international matches, FA Cup Finals, FA Cup semi-finals and Charity Shield games. It has also hosted numerous other sports, such as cricket, rugby union, speedway, greyhound racing, baseball and American football. The stadium's highest official attendance is 82,905, for a league match between Chelsea and Arsenal on 12 October 1935.

History

Early history

"Stamford Bridge" is considered to be a derivative of "Samfordesbrigge" meaning "the bridge at the sandy ford".[8] Eighteenth century maps show a "Stanford Creek" running along the route of what is now a railway line at the back of the East Stand as a tributary of the Thames. The upper reaches of this tributary have been known as Billingswell Ditch, Pools Creek and Counters Creek. In medieval times the creek was known as Billingwell Dyche, derived from "Billing's spring or stream". It formed the boundary between the parishes of Kensington and Fulham. By the 18th century the creek had become known as Counter's Creek, which is the name it has retained since.[9]

The stream had two local bridges: Stamford Bridge on the Fulham Road (also recorded as Little Chelsea Bridge) and Stanbridge on the King's Road, now known as Stanley Bridge. The existing Stamford Bridge was built of brick in 1860–1862 and has since been partly reconstructed.

Stamford Bridge opened in 1877 as a home for the London Athletic Club and was used almost exclusively for that purpose until 1904, when the lease was acquired by brothers Gus and Joseph Mears, who wanted to stage high-profile professional football matches there. However, previous to this, in 1898, Stamford Bridge played host to the World Championship of shinty between Beauly Shinty Club and London Camanachd.[10] Stamford Bridge was built close to Lillie Bridge, an older sports ground which had hosted the 1873 FA Cup Final and the first ever amateur boxing matches (among other things). It was initially offered to Fulham Football Club, but they turned it down for financial reasons. After considering the sale of the land to the Great Western Railway Company, the Mears decided to found their own football club, Chelsea, to occupy the ground as a rival to Fulham. Noted football ground architect Archibald Leitch, who had also designed Ibrox, Celtic Park, Craven Cottage and Hampden Park, was hired to construct the stadium. In its early days, Stamford Bridge stadium was served by a small railway station, Chelsea and Fulham railway station, which was later closed after World War II bombing.[11]

Stamford Bridge had an official capacity of around 100,000, making it the second largest ground in England after Crystal Palace. It was used as the FA Cup final venue. As originally constructed, Stamford Bridge was an athletics track and the pitch was initially located in the middle of the running track. This meant that spectators were separated from the field of play on all sides by the width of running track and, on the north and south sides, the separation was particularly large because the long sides of the running track considerably exceeded the length of the football pitch. The stadium had a single stand for 5,000 spectators on the east side. Designed by Archibald Leitch, it was an exact replica of the Stevenage Road Stand he had previously built at the re-developed Craven Cottage (and the main reason why Fulham had chosen not to move into the new ground). The other sides were all open in a vast bowl and thousands of tons of material excavated from the building of the Piccadilly line provided high terracing for standing spectators exposed to the elements on the west side.

In 1945, Stamford Bridge staged one of the most notable matches in its history. Soviet side FC Dynamo Moscow were invited to tour the United Kingdom at the end of the Second World War and Chelsea were the first side they faced. An estimated crowd of over 100,000 crammed into Stamford Bridge to watch an exciting 3–3 draw, with many spectators on the dog track and on top of the stands.

Crisis

In the early 1970s the club's owners embarked on an ambitious project to renovate Stamford Bridge. However, the cost of building the East Stand escalated out of control after shortages of materials and a builders' strike and the remainder of the ground remained untouched. The new East Stand was finished, but most of the (unusable) running tracks remained, and the new stand was also displaced by approximately 20 meters, compared to the pitch. The idea was to move the entire stadium towards the north. But due to the financial situation in the mid 1970s the other stands weren't rebuilt for another two decades. In the meantime, Chelsea struggled in the league, and attendances fell and debts increased. The club was relegated to the Second Division in 1975 and again in 1979, narrowly avoiding the drop into the Third Division in 1983 before finally returning to the First Division a year later.

The increase in the costs, combined with other factors, sent the club into decline. As a part of financial restructuring in the late 1970s, the freehold was separated from the club and when new Chelsea chairman Ken Bates bought the club for £1 in 1982, he did not buy the ground. A large chunk of the Stamford Bridge freehold was subsequently sold to property developers Marler Estates. The sale resulted in a long and acrimonious legal fight between Bates and Marler Estates. Marler Estates was ultimately forced into bankruptcy after a market crash in the early 1990s, allowing Bates to do a deal with its banks and re-unite the freehold with the club.

During the 1984–85 season, following a series of pitch invasions and fights by football hooligans during matches at the stadium, chairman Ken Bates erected an electric perimeter fence between the stands and the pitch – identical to the one which effectively controlled cattle on his dairy farm. However, the electric fence was never turned on and before long it was dismantled, due to the GLC blocking it from being switched on for health and safety reasons.[12]

Modernisation and redevelopment

With the Taylor Report arising from the Hillsborough disaster being published in January 1990 and ordering all top division clubs to have all-seater stadiums in time for the 1994–95 season, Chelsea's plan for a 34,000-seat stadium at Stamford Bridge was given approval by Hammersmith and Fulham council on 19 July 1990.[13]

The re-building of the stadium commenced and successive building phases during the 1990s eliminated the original running track. The construction of the East Stand some 20 years earlier had begun the process of eliminating the track. All stands, now roofed and all-seater, are immediately adjacent to the pitch. This structure captures and concentrates the noise of supporters. The pitch, the turnstiles, and the naming rights of the club are now owned by Chelsea Pitch Owners, an organisation set up to prevent the stadium from being purchased by property developers.

KSS Design Group (architects) designed the complete redevelopment of Stamford Bridge Stadium and its hotels, megastore, offices and residential buildings.[14]

Other uses

Stamford Bridge was the venue of the FA Cup Final from 1920 to 1922, before being replaced by Wembley Stadium in 1923. It has staged ten FA Cup semi-finals, ten Charity Shield matches, and three England matches, the last in 1932. It was one of the home venues for the representative London XI team that played in the original Inter-Cities Fairs Cup. The team played the home leg of the two-legged final at Stamford Bridge, drawing 2–2 with FC Barcelona; they lost the away leg 6–0, however.

Results of FA Cup Finals at Stamford Bridge

| Year | Attendance | Winner | Runner-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 50,018 | Aston Villa | 1–0 | Huddersfield Town |

| 1921 | 72,805 | Tottenham Hotspur | 1–0 | Wolverhampton Wanderers |

| 1922 | 53,000 | Huddersfield Town | 1–0 | Preston North End |

Stamford Bridge has also hosted a variety of other sporting events since Chelsea have occupied the ground. In October 1905 it hosted a rugby union match between the All Blacks and Middlesex,[15] and in 1914 hosted a baseball match between the touring New York Giants and the Chicago White Sox.[16] In 1908, Stamford Bridge was the venue for a Rugby League international between Great Britain and the touring New Zealand All Golds, who won 18-6.[17] In 1924 the stadium hosted the 1924 Women's Olympiad, the first international event for women in track and field in the UK. A speedway team operated from the stadium from 1929 until 1932, winning the Southern League in their opening season. Initially open meetings were held there in 1928. A nineteen-year-old junior rider, Charlie Biddle, was killed in a racing accident. In 1931, black cinders were laid onto the circuit suitable for use by speedway and athletics.[18] A midget car meeting reportedly attracted a crowd of 50,000 people in 1948.[18]

The ground was used in 1980 for the first major day-night floodlit cricket match between Essex and West Indies (although organised by Surrey) which was a commercial success; the following year it hosted the final of the inaugural Lambert & Butler county cricket competition.[19][20] It, however, failed and the experiment of playing cricket on football grounds was ended. Stamford Bridge briefly hosted American football – despite not being long enough for a regulation-size gridiron field – when the London Monarchs were based there in 1997.

Greyhound racing

The Greyhound Racing Association (GRA) brought greyhound racing to Stamford Bridge on 31 July 1933[21] and this forced the London Athletic Club to leave the venue.[22] Totalisator turnover in 1946 was nearly £6 million (£5,749,592);[23] to put this in perspective to football, the British transfer record at the same time in 1946 was £14,500.

On 1 August 1968 the GRA closed Stamford Bridge to greyhound racing quoting the fact that Stamford Bridge had to race on the same days as White City. An attempt by Chelsea to bring back greyhound racing to Stamford Bridge in 1976, to alleviate debts, failed when the GRA refused them permission to do so.[24]

Structure and facilities

The Bridge pitch is surrounded on each side by four covered all-seater stands, officially known as the Matthew Harding Stand (North), East stand, The Shed End (South) and West Stand. Each stand has at least two tiers & was constructed for entirely different reasons as part of separate expansion plans.

Matthew Harding Stand

The Matthew Harding Stand, previously known as the North Stand, is along the north edge of the pitch. In 1939, a small two storied North Stand including seating was erected. It was originally intended to span the entire northern end, but the outbreak of World War II and its aftermath compelled the club to keep the stand small. It was demolished and replaced by open terracing for standing supporters in 1976. The North Terrace was closed in 1993 and the present North Stand of two tiers (the Matthew Harding Stand) was then constructed at that end.

It is named after former Chelsea director Matthew Harding, whose investment helped transform the club in the early 1990s before his death in a helicopter accident on 22 October 1996. His investment in the club enabled construction of the stand which was completed in time for the 1996–97 season. It has two tiers and accommodates most season-ticket holders, giving it an excellent atmosphere, especially in the lower tier. Any proposal to enlarge the facility would necessitate demolition of the adjacent Chelsea F.C. Museum and Chelsea Health Club and Spa.

For some Champions League matches, this stand operates at reduced capacity, some entrances being obstructed by the presence of TV outside-broadcast vehicles.

East Stand

The only covered stand when Stamford Bridge was renovated into a football ground in 1905, the East Stand had a gabled corrugated iron roof, with around 6,000 seats and a terraced enclosure. The stand remained until 1973, when it was demolished in what was meant to be the opening phase of a comprehensive redevelopment of the stadium. The new stand was opened at the start of the 1974–75 season, but due to the ensuing financial difficulties at the club, it was the only part of the development to be completed.

The East Stand essentially survives in its 1973 three-tiered cantilevered form, although it has been much refurbished and modernised since. It is the heart of the stadium, housing the tunnel, dugout, dressing rooms, conference room, press centre, Audio-Visual and commentary box. The middle tier is occupied by facilities, clubs, and executive suites. The upper tier provides spectators with one of the best views of the pitch and it is the only section to have survived the extensive redevelopment of the 90s. Previously, it was the home to away supporters on the bottom tier. However, at the start of the 2005-06 season, then-manager José Mourinho requested that the family section move to this part of the stand, to boost team morale. Away fans were moved to the Shed End.

Shed End

The Shed End is along the south side of the pitch. In 1930, a new terrace was built on the south side, for more standing spectators. It was originally known as the Fulham Road End, but supporters nicknamed it 'The Shed' and this led the club to officially change its name. It became the most favoured spot for the loudest and most die-hard support, until the terrace was demolished in 1994, when all-seater stadia became compulsory by law as a safety measure in light of the Taylor Report following the Hillsborough disaster. The seated stand which replaced it is still known as the Shed End (see below).

The new stand opened in time for the 1997/98 season. Along with the Matthew Harding Stand, it is an area of the ground where many vocal fans congregate. The view from the upper tier is widely regarded as one of the best in the stadium. The Shed also contains the centenary museum and a memorial wall, where families of deceased fans are able to leave a permanent memorial of their loved ones, indicating their eternal support. A large chunk of the original wall from the back of the Shed End terrace still stands and runs along the south side of the stadium. It has recently been decorated with lights and large images of Chelsea legends. Since 2005, it has been where away supporters are housed; they are allocated 3,000 tickets towards the east side, roughly half of the capacity of the stand.

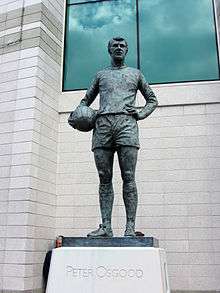

Peter Osgood's ashes were laid to rest under the shed end penalty spot in 2006.[25]

West Stand

In 1964–65, a seated West Stand was built to replace the existing terracing on the west side. Most of the West Stand consisted of rising ranks of wooden tip up seats on iron frames, but seating at the very front was on concrete forms known as "the Benches". The old West Stand was demolished in 1997 and replaced by the current West Stand. It has three tiers, in addition to a row of executive boxes that stretches the length of the stand.

The lower tier was built on schedule and opened in 1998. However, difficulties with planning permission meant that the stand was not fully completed until 2001. Construction of the stand almost caused another financial crisis, which would have seen the club fall into administration, but for the intervention of Roman Abramovich. In borrowing £70m from Eurobonds to finance the project, Ken Bates put Chelsea into a perilous financial position, primarily because of the repayment terms.

Now complete, the stand is the main external 'face' of the stadium, being the first thing fans see when entering the primary gate on Fulham Road. The Main Entrance is flanked by the Spackman and Speedie hospitality entrances, named after former Chelsea players Nigel Spackman and David Speedie. The stand also features the largest concourse area in the stadium, it is also known as the 'Great Hall' and is used for many functions at Stamford Bridge, including the Chelsea Player of the Year ceremony.

The aforementioned executive boxes, also known as the Millennium Suites, are the home of the majority of matchday hospitality guests. Each box is also named after a former Chelsea player (names in brackets):

- Tambling Suite (Bobby Tambling)

- Clarke Suite (Steve Clarke)

- Harris Suite (Ron Harris)

- 'Drakes' (Ted Drake)

- Bonetti (Peter Bonetti)

- Hollins (John Hollins)

In October 2010 a nine-foot statue of Chelsea forward Peter Osgood, created by Philip Jackson, was unveiled by Peter's widow, Lynn. It is positioned in a recess of the West Stand near the Millennium Reception.

A plaque on the side, written by official club historian Rick Glanvill, reads:

|

STAMFORD BRIDGE HAS MANY HEROES BUT ONLY ONE KING |

Pitch

The Bridge opened in 1877 as a home for the London Athletic Club and was used almost exclusively for that purpose until 1904. Subsequently, with the opening of the football club, the need for a pitch resulted in the construction of the pitch. In June 2015 significant upgrades were made to the undersoil-heating, drainage, and irrigation systems. Along with the installation a new hybrid grass pitch, this brought the pitch up to modern standards. The current pitch at the ground measures approximately 103 metres (112.6 yd) long by 67 metres (73.2 yd) wide, with a couple metres of run-off space on all sides. The south stand has by far the most run-off space being unto 3.5 metres deep.[26]

Chelsea Village and surroundings

When Stamford Bridge was redeveloped in the Ken Bates era, many additional features were added to the complex, including two hotels, apartments, bars, restaurants, the Chelsea Megastore, and an interactive visitor attraction called Chelsea World of Sport. The intention was that these facilities would provide extra revenue to support the football side of the business, but they were less successful than hoped, and before the Abramovich takeover in 2003, the debt taken on to finance them was a major burden on the club. Soon after the takeover, a decision was taken to drop the "Chelsea Village" brand and refocus on Chelsea as a football club. However, the stadium is sometimes still referred to as part of Chelsea Village or "The Village".[27]

Centenary Museum

2005 saw the opening of a new club museum, known as the Chelsea Museum or the Centenary Museum, to mark the one hundredth anniversary of the club. The museum is located in the former Shed Galleria. Visitors are able to visit the WAGs lounge and then watch an introductory video message from the former vice-president Richard Attenborough. They are then guided decade by decade through the club's history seeing old programmes, past shirts, José Mourinho's coat and other memorabilia. A motto on the wall of the museum reads "I am not from the bottle. I am a special one.",[28] a reference to Mourinho's famous quote upon signing as manager for Chelsea.[29]

On 6 June 2011 a new museum with improved and interactive exhibits opened behind the Matthew Harding stand. It is the largest football museum in London.[30]

Megastore

The current Megastore is on the south-west corner of the stadium. The store is two floors. The ground floor mainly consists of souvenirs and children's gear. The first floor is filled with training jerseys, coats, and replica jerseys. There are also two smaller shops, one located at the Stamford Gate entrance and the other inside the new museum building behind the Matthew Harding stand.[31]

Future: Stamford Bridge Redevelopment Project

Under Roman Abramovich's control, the club has announced that it wants to develop Stamford Bridge to around 55,000 to 60,000 seats.[32] However, its location in a heavily built-up part of Inner London, in between a main road and two railway lines, makes this difficult. The dispersal of an additional 13,000 to 15,000 fans into the residential roads of the Moore Park Estate & areas surrounding Stamford Bridge would undoubtedly create congestion.

Exploration of alternative sites

Alternative possibilities include moving from Stamford Bridge to a location such as the Earls Court Exhibition Centre, White City, Battersea Power Station, the Imperial Road Gasworks (off the Kings Road on the Fulham and Chelsea border) and the Chelsea Barracks.[33] But, under the Chelsea Pitch Owners articles of association, the club would relinquish the name 'Chelsea Football Club' should it ever move from Stamford Bridge.[34] On 3 October 2011, the club issued a statement, in which it proposed to buy back the freehold from Chelsea Pitch Owners Plc. This has been widely speculated as the first move by the football club to begin their movement away from the current stadium. On 27 October 2011, Chelsea F.C. failed in its bid to buy back the freehold, with shareholders of the CPO voting against selling the land.[35] On 4 May 2012, Chelsea F.C. announced a bid to purchase Battersea Power Station, as part of plans to build a new 60,000-seater stadium on the site.[36] Though they were not the preferred bidders, they released artistic impressions of the proposed stadium at the BPS on 22 June 2012.

On 17 June 2014, club owner Roman Abramovich released a statement, saying that he had commissioned a study of the area from Fulham Broadway to Stamford Bridge and beyond by West London-based architects Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands. The study was commissioned to see if there are any ways Chelsea could expand Stamford Bridge.

Current plans

Chelsea have plans to expand the stadium to 60,000.[37]

Planning permission

It was announced on 5 January 2017 that the planners at Hammersmith and Fulham council had approved the redevelopment of the stadium.[38] The whole of Chelsea village would be demolished and the new stadium would include a new club shop, museum, a bar and restaurant. The two existing hotels, restaurants, bars and spa would be relocated.

On 6 March 2017 full permission was given to redevelop Stamford Bridge by the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, who said the "high quality and spectacular design" would add to the capital's "fantastic array of sporting arenas".[39]

Playing away from Stamford Bridge

As part of the Redevelopment of the stadium it was determined that the club would have to find an alternative site to play home games for the duration of the construction of the stadium. It was reported that the length of time could vary between 3–4 years. The club has said they will keep their supporters informed as the study progresses. On 28 September 2014 it was revealed that Chelsea had enquired about a temporary move to Twickenham Stadium to help facilitate an expansion of Stamford Bridge.[40]

Media reported in February 2016 that Chelsea had agreed a deal to use Wembley Stadium for three seasons beginning in 2017-18 for £20 million.[41] Although Chelsea wanted exclusive rights to Wembley, the FA suggested that fellow Londoners Tottenham Hotspur F.C. and Chelsea rivals share the stadium for the 2017–18 season only, as Spurs build their new stadium.[41] The FA wanted to show no favourites in using the national stadium.[41]

Legal hurdles

In May 2017, the Crosthwaites family launched legal proceedings in the form of an injunction, in order to prevent Chelsea from expanding Stamford Bridge. The family's argument was that there will be almost 17,000 hospitality seats, 28% of the total. They would prefer to throttle the growth of Chelsea F.C. by legally forcing them to limit hospitality seating. This, despite the fact that they were offered legal advice worth £50,000, and further compensation understood to be in the region of a six-figure sum, in exchange for waiving their 'right to light' in their home.[42] The club then sought the help of Hammersmith & Fulham Council in order to continue with the Stamford Bridge Redevelopment Project. In January 2018 the council sided with the club, by planning to use its powers under planning law to buy the air rights over part of Stamford Bridge and the railway line which sits between the stadium and the two affected homes. It would then lease the land back to Chelsea and railway operators Network Rail, meaning the Crosthwaites would be entitled to compensation but would not be able to prevent the redevelopment.[43]

Scope of the redevelopment

The Stamford Redevelopment Project encompasses an area of around 12.1 acres (48967 m2). The northern boundaries are formed by Railway lines to the north & the east, while Fulham Road forms the southern boundary. Sir Oswald Stoll Mansions form the western frontier. The club carried out a public consultation in June 2017 to gain feedback about the stadium design. The project is expected to be constructed in a phased manner.[44]

- Phase I: The first phase involves the tearing down of the club museum, the health club, the health spa, Millennium & Copthrone Hotels & the entirety of Chelsea village. This phase intends to be completed while the club continue to play at Stamford Bridge & is expected to last a year. The main contractor of this phase of the project has yet to be determined.

- Phase II: This phase is expected to cover the demolition of the stadium and the facilities contained within it.

- Phase III: This involves the building of a decked surface from Fulham Broadway Station in the north west & north to Fulham road in the south barring the land not owned as part of the freehold of stamford bridge. From Sir Oswald Stoll Mansions in the west to the Railway lines in the east. This phase will also involve a reduced level dig.

- Phase IV: Consists of building the new stadium.

Suspension of planned redevelopment

On 31 May 2018 the club released a statement via their website stating that the "Chelsea Football Club announces today that it has put its new stadium project on hold. No further pre-construction design and planning work will occur." The statement went on to elaborate that "The club does not have a time frame set for reconsideration of its decision. The decision was made due to the current unfavourable investment climate."[45]

Statistics

Records

Average attendances

Reception

| Season | Stadium capacity | Average attendance | % of capacity | Ranking within the Premier League |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018–19 | 40,853 | 40,721 | 99.7% | 8th highest |

| 2017–18 | 41,631 | 41.282 | 99.2% | 8th highest |

| 2016–17 | 41,623 | 41,508 | 99.7% | 6th highest |

| 2015–16 | 41,798 | 41,500 | 99.2% | 7th highest |

| 2014–15 | 41,798 | 41,546 | 99.4% | 7th highest |

| 2013–14 | 41,798 | 41,482 | 99.3% | 6th highest |

| 2012–13 | 41,798 | 41,462 | 99.2% | 6th highest |

| 2011–12 | 42,449 | 41.478 | 97.7% | 6th highest |

| 2010–11 | 42,449 | 41,435 | 97.6% | 6th highest |

| 2009–10 | 42,055 | 41,423 | 98.5% | 5th highest |

| 2008–09 | 42,055 | 41.588 | 98.9% | 6th highest |

| 2007–08 | 42,055 | 41.397 | 97.7% | 7th highest |

| 2006–07 | 42,360 | 41.542 | 98.1% | 5th highest |

| 2005–06 | 42,360 | 41.902 | 98.9% | 5th highest |

| 2004–05 | 42,360 | 41,870 | 98.8% | 5th highest |

| 2003–04 | 42,360 | 41,235 | 97.3% | 5th highest |

| 2002–03 | 42,055 | 39,784 | 94.6% | 4th highest |

| 2001–02 | 42,055 | 39,030 | 92.8% | 6th highest |

| 2000–01 | 42,055 | 34,700 | 82.5% | 8th highest |

| 1999–00 | 42,055 | 34,532 | 82.1% | 9th highest |

- Premier League

- 1992–93: 18,755

- 1993–94: 19,211

- 1994–95: 21,062

- 1995–96: 25,598

- 1996–97: 27,617

- 1997–98: 33,387

- 1998–99: 34,571

- 1999–00: 34,532

- 2000–01: 34,700

- 2001–02: 38,834

- 2002–03: 39,784

- 2003–04: 41,234

- 2004–05: 41,870

- 2005–06: 41,902

- 2006–07: 41,909

- 2007–08: 41,397

- 2008–09: 41,590

- 2009–10: 41,425

- 2010–11: 41,435[46]

- 2011–12: 41,478[46]

- 2012–13: 41,462[46]

- 2013–14: 41,490[47]

- 2014–15: 41,546[48]

- 2015–16: 41,500[49]

- 2016–17: 41,508[50]

- 2017–18: 41,282[51]

- 2018–19: 40,437[52]

International matches

- 11 December 1909: England Amateurs 9–1 Netherlands

- 5 April 1913: England 1–0 Scotland

- 20 November 1929: England 6–0 Wales

- 7 December 1932: England 4–3 Austria

- 11 May 1946: England 4–1 Switzerland (Victory International)

- 25 March 2013: Brazil 1–1 Russia [53]

Access

Stamford Bridge is easily accessible by public transport.

| Service | Station/Stop | Line/Route | Walking distance from Stamford Bridge |

|---|---|---|---|

| London Buses | Walham Green | 11, 14, 211, 414, N11 | 200 yards (180 m) 2 mins |

| Fulham Broadway/ Fulham Town Hall | 28, 295, 391, 424, N28[54] | 0.2 miles (0.32 km) 5 mins | |

| London Underground | Fulham Broadway | 0.2 miles (0.32 km) 5 mins | |

| Earl's Court | 1.1 miles (1.8 km) 27 mins | ||

| National Rail (London Overground and Southern Railway) |

West Brompton (interchange with District Line for Fulham Broadway) Imperial Wharf | West London Line | 0.8 miles (1.3 km) 20 mins 0.625 miles (1.006 km) 13 mins |

| London River Services | Chelsea Harbour Pier | London River Services | 0.75 miles (1.21 km) 15 mins |

See also

References

- "Premier League Handbook 2019/20" (PDF). Premier League. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Attendances". Chelsea F.C. Archived from the original on 26 June 2014.

- Kostka, Kevin (23 May 2014). "Stamford Bridge is getting a makeover". We Ain't Got No History.

- "Stadium History: Building a Bridge". Chelsea F.C. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Premier Talents Brings Brazilian Blue to the Bridge". chelseafc.com. 14 January 2011. Archived from the original on 17 January 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- Winter, Henry (26 February 2011). "Chelsea v Manchester United battle has lost its edge". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- MacInnes, Paul (12 January 2017). "Chelsea get permission for new expanded Stamford Bridge stadium". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- Fèret, Charles James (1900). "Chapter XVI: Fulham Road—(continued). Section IV.-Walham Green to Stamford Bridge. South Side.". Fulham Old and New: Being an Exhaustive History of the Ancient Parish of Fulham, Vol. II. London: The Leadenhall Press. pp. 225–226. OCLC 926302483.

- Gover, J. E. B.; Mawer, Allen; Stenton, F. M. (1922). The Place-Names of Middlesex (Including Those Parts of the County of London Formerly Contained Within the Boundaries of the Old County). London: Longmans, Green and Company.

- Bale, Karen (9 September 2006). "It's the Theatre of Drams". Daily Record. Glasgow. Archived from the original on 24 January 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- Catford, Nick (cited as "source") (17 May 2017). "Chelsea & Fulham". Disused Stations. Subterranea Britannica. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Football: News, opinion, previews, results & live scores – Mirror Online". mirrorfootball.co.uk. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- The Times and The Sunday Times Archive

- "KSS Design".KSS Design Group

- "All Blacks". Rugbyfootballhistory.com. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- "Countdown to SABR Day 2011". BaseballGB.co.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- "The All Golds". Edgar Wrigley. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Bamford, R & Jarvis J.(2001). Homes of British Speedway. ISBN 0-7524-2210-3

- "Lighting up Stamford Bridge stars". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- "The forgotten story of … Britain's first floodlit cricket match". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ""Greyhound Racing." Times [London, England] 2 Jan. 1933". The Times Digital Archive.

- Tarter, P Howard (1949). Greyhound Racing Encyclopedia. Fleet Publishing Company Ltd.

- Particulars of Licensed tracks, table 1 Licensed Dog Racecourses. Licensing Authorities. 1946.

- "Remember When - August 1976". Greyhound Star. 2018.

- "10 Facts You Need to Know About Club Legend Peter Osgood | Official Site | Chelsea Football Club". ChelseaFC. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- "Stamford Bridge is getting a makeover". We Ain't Got No History. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- https://flashbak.com/chelsea-fc-the-stamford-bridge-story-in-photos-3533/

- "BBC – Phil McNulty: Mourinho still pure theatre". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Jason Cowley, NS Man of the year – José Mourinho – New Statesman

- "Chelsea F.C. Museum". Archived from the original on 16 May 2011.

- "Stadium Megastore". Chelsea Football Club. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- "Kenyon confirms Blues will stay at Stamford Bridge". RTÉ Sport. 12 April 2006. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 17 November 2007.

- "Chelsea plan Bridge redevelopment". BBC. 20 January 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2007.

- Glanvill, Rick (2006). Chelsea FC: The Official Biography. pp. 91–92.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- "Chelsea Bid For Battersea Site".

- "Chelsea submit plans to increase Stamford Bridge capacity to 60,000". The Guardian. 1 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Hall, Joe (5 January 2017). "Chelsea redevelopment plans for the Bridge get thumbs up".

- "Chelsea Football Club's Stamford Bridge plans approved by mayor". BBC News. 6 March 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- "Chelsea explore possibility of temporary Twickenham move". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/36266068

- "Chelsea stadium: £1bn Stamford Bridge hit by family dispute". BBC Sport. 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "Boost for Chelsea after council ruling in battle of Stamford Bridge - Independent.ie". Independent.ie. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- Staplehurst, Jack (3 May 2017). "Chelsea face major Stamford Bridge setback: Club resigned to new four-year plan". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "Stadium plans on hold | Official Site | Chelsea Football Club". ChelseaFC. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- "England historical attendance and performance". european-football-statistics.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- "Barclays Premier League Statistics". ESPN FC. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- "Premier League 2014/2015 » Attendance » Home matches". worldfootball.net. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- "Premier League 2015/2016 » Attendance » Home matches". worldfootball.net. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- "Premier League 2016/2017 » Attendance » Home matches". worldfootball.net. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Premier League 2017/2018 » Attendance » Home matches". worldfootball.net. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Premier League 2018/2019 » Attendance » Home matches". worldfootball.net. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- "Brazil 1 Russia 1: match report". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Transport for London, Windsor House, 42-50 Victoria Street, London SW1H 0TL, enquire@tfl.gov.uk. "Home – Transport for London" (PDF). tfl.gov.uk. Retrieved 2 December 2015.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stamford Bridge (stadium). |

| Preceded by Old Trafford Manchester |

FA Cup Final venue 1920–1922 |

Succeeded by Wembley Stadium London |

| Preceded by Olympiastadion Munich |

UEFA Women's Champions League Final venue 2013 |

Succeeded by Estádio do Restelo Lisbon |