Mexico City

Mexico City (Spanish: Ciudad de México, locally [sjuˈða(ð) ðe ˈmexiko] (![]()

Mexico City | |

|---|---|

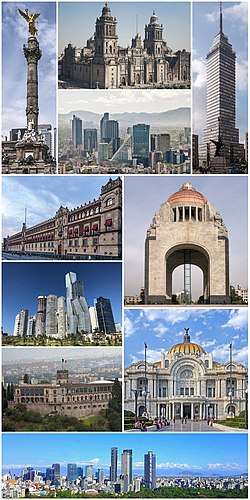

From top and left: Angel of Independence, Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral, Paseo de la Reforma, Torre Latinoamericana, National Palace, Parque La Mexicana in Santa Fe, Monumento a la Revolución, Chapultepec Castle, Palacio de Bellas Artes and Paseo de la Reforma | |

Flag  Coat of arms  Government logo | |

| Nickname(s): CDMX | |

| Motto(s): La Ciudad de los Palacios (The City of Palaces) | |

_in_Mexico_(zoom).svg.png) Mexico City within Mexico | |

Mexico City Location within Mexico  Mexico City Mexico City (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 19°26′N 99°8′W | |

| Country | |

| Founded |

|

| Founded by |

|

| Government | |

| • Mayor | |

| • Senators[5] |

|

| • Deputies[6] | Federal Deputies

|

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 1,485 km2 (573 sq mi) |

| Ranked 32nd | |

| Elevation | 2,240 m (7,350 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 3,930 m (12,890 ft) |

| Population (2015)[9] | |

| • Capital city | 8,918,653 |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Density | 6,000/km2 (16,000/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | 1st |

| • Urban | 21 million[10] |

| Demonyms |

|

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| Postal code | 00–16 |

| Area code | 55/56 |

| ISO 3166 code | MX-CMX |

| Patron Saint | Philip of Jesus (Spanish: San Felipe de Jesús) |

| HDI | |

| GDP (Nominal) | $266 billion[12] |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Historic center of Mexico City, Xochimilco and Central University City Campus of the UNAM |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 1987, 2007 (11th, 31st sessions) |

| Reference no. | 412, 1250 |

| State Party | Mexico |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

| ^ b. Area of Mexico City that includes non-urban areas at the south | |

The 2009 population for the city proper was approximately 8.84 million people,[17] with a land area of 1,485 square kilometers (573 sq mi).[18] According to the most recent definition agreed upon by the federal and state governments, the population of Greater Mexico City is 21.3 million, which makes it the second largest metropolitan area of the Western Hemisphere, the eleventh-largest agglomeration (2017), and the largest Spanish-speaking city in the world.[19]

Greater Mexico City has a GDP of $411 billion in 2011, making Greater Mexico City one of the most productive urban areas in the world.[20] The city was responsible for generating 15.8% of Mexico's GDP, and the metropolitan area accounted for about 22% of total national GDP.[21] If it were an independent country, in 2013, Mexico City would be the fifth-largest economy in Latin America, five times as large as Costa Rica and about the same size as Peru.[22]

Mexico's capital is both the oldest capital city in the Americas and one of two founded by indigenous people, the other being Quito, Ecuador. The city was originally built on an island of Lake Texcoco by the Aztecs in 1325 as Tenochtitlan, which was almost completely destroyed in the 1521 siege of Tenochtitlan and subsequently redesigned and rebuilt in accordance with the Spanish urban standards. In 1524, the municipality of Mexico City was established, known as México Tenochtitlán,[23] and as of 1585, it was officially known as Ciudad de México (Mexico City).[23] Mexico City was the political, administrative, and financial center of a major part of the Spanish colonial empire.[24] After independence from Spain was achieved, the federal district was created in 1824.

After years of demanding greater political autonomy, residents were finally given the right to elect both a head of government and the representatives of the unicameral Legislative Assembly by election in 1997. Ever since, left-wing parties (first the Party of the Democratic Revolution and later the National Regeneration Movement) have controlled both of them.[25] The city has several progressive policies, such as abortion on demand, a limited form of euthanasia, no-fault divorce, and same-sex marriage.

On 29 January 2016, it ceased to be the Federal District (Spanish: Distrito Federal or D.F.) and is now officially known as Ciudad de México (or CDMX), with a greater degree of autonomy.[26][27] A clause in the Constitution of Mexico, however, prevents it from becoming a state within the Mexican federation, as it is the seat of power in the country, unless the capital of the country were to be relocated elsewhere.[28]

History

The oldest signs of human occupation in the area of Mexico City are those of the "Peñon woman" and others found in San Bartolo Atepehuacan (Gustavo A. Madero). They were believed to correspond to the lower Cenolithic period (9500-7000 BC).[29] However, recent studies place the age of the Penon woman at 12,700 years old, making her one of the Americas' oldest human remains.[30] Its origin due to its mitochondrial DNA suggests Asian,[31] or Caucasian having an appearance like Western European whites,[32][30] or Australian.

The area was the destination of the migrations of the Teochichimecas during the 8th and 13th centuries, peoples that would give rise to the Toltec, and Mexica (Aztecs) cultures. The latter arrived around the 14th century to settle first on the shores of the lake.

Aztec period

.jpg)

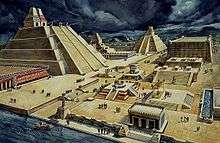

The city of Mexico-Tenochtitlan was founded by the Mexica people in 1325. The old Mexica city that is now simply referred to as Tenochtitlan was built on an island in the center of the inland lake system of the Valley of Mexico, which it shared with a smaller city-state called Tlatelolco.[33] According to legend, the Mexicas' principal god, Huitzilopochtli, indicated the site where they were to build their home by presenting a golden eagle perched on a prickly pear devouring a rattlesnake.[34]

Between 1325 and 1521, Tenochtitlan grew in size and strength, eventually dominating the other city-states around Lake Texcoco and in the Valley of Mexico. When the Spaniards arrived, the Aztec Empire had reached much of Mesoamerica, touching both the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.[34]

Spanish conquest

After landing in Veracruz, Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés advanced upon Tenochtitlan with the aid of many of the other native peoples,[35] arriving there on 8 November 1519.[36] Cortés and his men marched along the causeway leading into the city from Iztapalapa, and the city's ruler, Moctezuma II, greeted the Spaniards; they exchanged gifts, but the camaraderie did not last long.[37] Cortés put Moctezuma under house arrest, hoping to rule through him.[38]

Tensions increased until, on the night of 30 June 1520 – during a struggle known as "La Noche Triste" – the Aztecs rose up against the Spanish intrusion and managed to capture or drive out the Europeans and their Tlaxcalan allies.[39] Cortés regrouped at Tlaxcala. The Aztecs thought the Spaniards were permanently gone, and they elected a new king, Cuitláhuac, but he soon died; the next king was Cuauhtémoc.[40]

Cortés began a siege of Tenochtitlan in May 1521. For three months, the city suffered from the lack of food and water as well as the spread of smallpox brought by the Europeans.[35] Cortés and his allies landed their forces in the south of the island and slowly fought their way through the city.[41] Cuauhtémoc surrendered in August 1521.[35] The Spaniards practically razed Tenochtitlan during the final siege of the conquest.[36]

Rebuilding

Cortés first settled in Coyoacán, but decided to rebuild the Aztec site to erase all traces of the old order.[36] He did not establish a territory under his own personal rule, but remained loyal to the Spanish crown. The first Spanish viceroy arrived in Mexico City fourteen years later. By that time, the city had again become a city-state, having power that extended far beyond its borders.[42]

Although the Spanish preserved Tenochtitlan's basic layout, they built Catholic churches over the old Aztec temples and claimed the imperial palaces for themselves.[42] Tenochtitlan was renamed "Mexico" because the Spanish found the word easier to pronounce.[36]

Growth of colonial Mexico City

The city had been the capital of the Aztec empire and in the colonial era, Mexico City became the capital of New Spain. The viceroy of Mexico or vice-king lived in the viceregal palace on the main square or Zócalo. The Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral, the seat of the Archbishopric of New Spain, was constructed on another side of the Zócalo, as was the archbishop's palace, and across from it the building housing the city council or ayuntamiento of the city.

A late seventeenth-century painting of the Zócalo by Cristóbal de Villalpando depicts the main square, which had been the old Aztec ceremonial center. The existing central place of the Aztecs was effectively and permanently transformed to the ceremonial center and seat of power during the colonial period, and remains to this day in modern Mexico, the central place of the nation.

The rebuilding of the city after the siege of Tenochtitlan was accomplished by the abundant indigenous labor in the surrounding area. Franciscan friar Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, one of the Twelve Apostles of Mexico who arrived in New Spain in 1524, described the rebuilding of the city as one of the afflictions or plagues of the early period:

The seventh plague was the construction of the great City of Mexico, which, during the early years used more people than in the construction of Jerusalem. The crowds of laborers were so numerous that one could hardly move in the streets and causeways, although they are very wide. Many died from being crushed by beams, or falling from high places, or in tearing down old buildings for new ones.[43]

Preconquest Tenochtitlan was built in the center of the inland lake system, with the city reachable by canoe and by wide causeways to the mainland. The causeways were rebuilt under Spanish rule with indigenous labor.

Colonial Spanish cities were constructed on a grid pattern, if no geographical obstacle prevented it. In Mexico City, the Zócalo (main square) was the central place from which the grid was then built outward. The Spanish lived in the area closest to the main square in what was known as the traza, in orderly, well laid-out streets. Indian residences were outside that exclusive zone and houses were haphazardly located.[44]

Spaniards sought to keep Indians separate from Spaniards but since the Zócalo was a center of commerce for Indians, they were a constant presence in the central area, so strict segregation was never enforced.[45] At intervals Zócalo was where major celebrations took place as well as executions. It was also the site of two major riots in the seventeenth century, one in 1624, the other in 1692.[46]

The city grew as the population did, coming up against the lake's waters. As the depth of the lake water fluctuated, Mexico City was subject to periodic flooding. A major labor draft, the desagüe, compelled thousands of Indians over the colonial period to work on infrastructure to prevent flooding. Floods were not only an inconvenience but also a health hazard, since during flood periods human waste polluted the city's streets. By draining the area, the mosquito population dropped as did the frequency of the diseases they spread. However, draining the wetlands also changed the habitat for fish and birds and the areas accessible for Indian cultivation close to the capital.[47]

The 16th century saw a proliferation of churches, many of which can still be seen today in the historic center.[42] Economically, Mexico City prospered as a result of trade. Unlike Brazil or Peru, Mexico had easy contact with both the Atlantic and Pacific worlds. Although the Spanish crown tried to completely regulate all commerce in the city, it had only partial success.[48]

The concept of nobility flourished in New Spain in a way not seen in other parts of the Americas. Spaniards encountered a society in which the concept of nobility mirrored that of their own. Spaniards respected the indigenous order of nobility and added to it. In the ensuing centuries, possession of a noble title in Mexico did not mean one exercised great political power, for one's power was limited even if the accumulation of wealth was not.[49] The concept of nobility in Mexico was not political but rather a very conservative Spanish social one, based on proving the worthiness of the family. Most of these families proved their worth by making fortunes in New Spain outside of the city itself, then spending the revenues in the capital, building churches, supporting charities and building extravagant palatial homes. The craze to build the most opulent residence possible reached its height in the last half of the 18th century. Many of these palaces can still be seen today, leading to Mexico City's nickname of "The city of palaces" given by Alexander Von Humboldt.[36][42][49]

The Grito de Dolores ("Cry of Dolores"), also known as El Grito de la Independencia ("Cry of Independence"), marked the beginning of the Mexican War of Independence. The Battle of Guanajuato, the first major engagement of the insurgency, occurred four days later. After a decade of war, Mexico's independence from Spain was effectively declared in the Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire on 27 September 1821.[50] Agustín de Iturbide is proclaimed Emperor of the First Mexican Empire by Congress, crowned in the Cathedral of Mexico. Unrest followed for the next several decades, as different factions fought for control of Mexico.[51]

The Mexican Federal District was established by the new government and by the signing of their new constitution, where the concept of a federal district was adapted from the United States Constitution.[52] Before this designation, Mexico City had served as the seat of government for both the State of Mexico and the nation as a whole. Texcoco de Mora and then Toluca became the capital of the State of Mexico.[53]

The Battle of Mexico City in the U.S.–Mexican War of 1847

During the 19th century, Mexico City was the center stage of all the political disputes of the country. It was the imperial capital on two occasions (1821-1823 and 1864-1867), and of two federalist states and two centralist states that followed innumerable coups d'états in the space of half a century before the triumph of the Liberals after the Reform War. It was also the objective of one of the two French invasions to Mexico (1861-1867), and occupied for a year by American troops in the framework of the Mexican–American War (1847-1848).

The Battle for Mexico City was the series of engagements from 8 to 15 September 1847, in the general vicinity of Mexico City during the U.S. Mexican War. Included are major actions at the battles of Molino del Rey and Chapultepec, culminating with the fall of Mexico City. The U.S. Army under Winfield Scott scored a major success that ended the war. The American invasion into the Federal District was first resisted during the Battle of Churubusco on 8 August, where the Saint Patrick's Battalion, which was composed primarily of Catholic Irish and German immigrants but also Canadians, English, French, Italians, Poles, Scots, Spaniards, Swiss, and Mexicans, fought for the Mexican cause, repelling the American attacks. After defeating the Saint Patrick's Battalion, the Mexican–American War came to a close after the United States deployed combat units deep into Mexico resulting in the capture of Mexico City and Veracruz by the U.S. Army's 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Divisions.[55] The invasion culminated with the storming of Chapultepec Castle in the city itself.[56]

During this battle, on 13 September, the 4th Division, under John A. Quitman, spearheaded the attack against Chapultepec and carried the castle. Future Confederate generals George E. Pickett and James Longstreet participated in the attack. Serving in the Mexican defense were the cadets later immortalized as Los Niños Héroes (the "Boy Heroes"). The Mexican forces fell back from Chapultepec and retreated within the city. Attacks on the Belén and San Cosme Gates came afterwards. The treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in what is now the far north of the city.[57]

Porfirian era (1876–1911)

Events such as the Mexican–American War, the French Intervention and the Reform War left the city relatively untouched and it continued to grow, especially during the rule of President Porfirio Díaz. During this time the city developed a modern infrastructure, such as roads, schools, transportation systems and communication systems. However the regime concentrated resources and wealth into the city while the rest of the country languished in poverty.

Under the rule of Porfirio Díaz, Mexico City experienced a massive transformation. Díaz's goal was to create a city which could rival the great European cities. He and his government came to the conclusion that they would use Paris as a model, while still containing remnants of Amerindian and Hispanic elements. This style of Mexican-French fusion architecture became colloquially known as Porfirian Architecture. Porfirian architecture became very influenced by Paris' Haussmannization.

During this era of Porfirian rule, the city underwent an extensive modernization. Many Spanish Colonial style buildings were destroyed, replaced by new much larger Porfirian institutions and many outlying rural zones were transformed into urban or industrialized districts with most having electrical, gas and sewage utilities by 1908. While the initial focus was on developing modern hospitals, schools, factories and massive public works, perhaps the most long-lasting effects of the Porfirian modernization were creation of the Colonia Roma area and the development of Reforma Avenue. Many of Mexico City's major attractions and landmarks were built during this era in this style.

Diaz's plans called for the entire city to eventually be modernized or rebuilt in the Porfirian/French style of the Colonia Roma; but the Mexican Revolution began soon afterward and the plans never came to fruition, with many projects being left half-completed. One of the best examples of this is the Monument to the Mexican Revolution. Originally the monument was to be the main dome of Diaz's new senate hall, but when the revolution erupted only the dome of the senate hall and its supporting pillars were completed, this was subsequently seen as a symbol by many Mexicans that the Porfirian era was over once and for all and as such, it was turned into a monument to victory over Diaz.

Mexican Revolution (1910–1920)

The capital escaped the worst of the violence of the ten-year conflict of the Mexican Revolution. The most significant episode of this period for the city was the February 1913 la Decena Trágica ("The Ten Tragic Days"), when forces counter to the elected government of Francisco I. Madero staged a successful coup. The center of the city was subjected to artillery attacks from the army stronghold of the ciudadela or citadel, with significant civilian casualties and the undermining of confidence in the Madero government. Victoriano Huerta, chief general of the Federal Army, saw a chance to take power, forcing Madero and Pino Suarez to sign resignations. The two were murdered later while on their way to Lecumberri prison.[58] Huerta's ouster in July 1914 saw the entry of the armies of Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, but the city did not experience violence. Huerta had abandoned the capital and the conquering armies marched in. Venustiano Carranza's Constitutionalist faction ultimately prevailed in the revolutionary civil war and Carranza took up residence in the presidential palace.

20th century to present

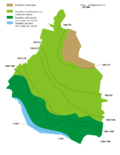

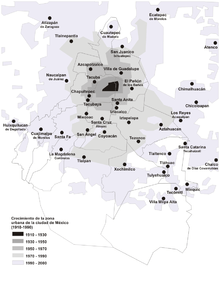

The history of the rest of the 20th century to the present focuses on the phenomenal growth of the city and its environmental and political consequences. In 1900, the population of Mexico City was about 500,000.[59] The city began to grow rapidly westward in the early part of the 20th century[42] and then began to grow upwards in the 1950s, with the Torre Latinoamericana becoming the city's first skyscraper.[35]

The rapid development of Mexico City as a center for modernist architecture was most fully manifested in the mid-1950s construction of the Ciudad Universitaria, Mexico City, the main campus of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Designed by the most prestigious architects of the era, including Mario Pani, Eugenio Peschard, and Enrique del Moral, the buildings feature murals by artists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Chávez Morado. It has since been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[60]

The 1968 Olympic Games brought about the construction of large sporting facilities.[42] In 1969, the Metro system was inaugurated.[35] Explosive growth in the population of the city started in the 1960s, with the population overflowing the boundaries of the Federal District into the neighboring State of Mexico, especially to the north, northwest, and northeast. Between 1960 and 1980 the city's population more than doubled to nearly 9 million.[42]

In 1980 half of all the industrial jobs in Mexico were located in Mexico City. Under relentless growth, the Mexico City government could barely keep up with services. Villagers from the countryside who continued to pour into the city to escape poverty only compounded the city's problems. With no housing available, they took over lands surrounding the city, creating huge shantytowns that extended for many miles.[51] This caused serious air pollution in Mexico City and water pollution problems, as well as subsidence due to overextraction of groundwater.[61] Air and water pollution has been contained and improved in several areas due to government programs, the renovation of vehicles and the modernization of public transportation.

The autocratic government that ruled Mexico City since the Revolution was tolerated, mostly because of the continued economic expansion since World War II. This was the case even though this government could not handle the population and pollution problems adequately. Nevertheless, discontent and protests began in the 1960s leading to the massacre of an unknown number of protesting students in Tlatelolco.[51]

Three years later, a demonstration in the Maestros avenue, organized by former members of the 1968 student movement, was violently repressed by a paramilitary group called "Los Halcones", composed of gang members and teenagers from many sports clubs who received training in the U.S.

On Thursday, 19 September 1985, at 7:19 am CST, Mexico City was struck by an earthquake of magnitude 8.1[62] on the Richter magnitude scale. Although this earthquake was not as deadly or destructive as many similar events in Asia and other parts of Latin America,[63] it proved to be a disaster politically for the one-party government. The government was paralyzed by its own bureaucracy and corruption, forcing ordinary citizens to create and direct their own rescue efforts and to reconstruct much of the housing that was lost as well.[64]

However, the last straw may have been the controversial elections of 1988. That year, the presidency was set between the P.R.I.'s candidate, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, and a coalition of left-wing parties led by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, son of the former president Lázaro Cárdenas. The counting system "fell" because coincidentally the light went out and suddenly, when it returned, the winning candidate was Salinas, even though Cárdenas had the upper hand.

As a result of the fraudulent election, Cárdenas became a member of the Party of the Democratic Revolution. Discontent over the election eventually led Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas to become the first elected mayor of Mexico City in 1997. Cárdenas promised a more democratic government, and his party claimed some victories against crime, pollution, and other major problems. He resigned in 1999 to run for the presidency.

Geography

| Major elevations in Mexico City | |

| |

| Name | Altitude |

| Ajusco Volcano | 3,930 metres (12,890 ft) |

| Tláloc Volcano | 3,690 metres (12,110 ft) |

| Pelado Volcano | 3,620 metres (11,880 ft) |

| Cuauhtzin Volcano | 3,510 metres (11,520 ft) |

| Chichinauhtzin Volcano | 3,490 metres (11,450 ft) |

Mexico City is located in the Valley of Mexico, sometimes called the Basin of Mexico. This valley is located in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt in the high plateaus of south-central Mexico.[65][66] It has a minimum altitude of 2,200 meters (7,200 feet) above sea level and is surrounded by mountains and volcanoes that reach elevations of over 5,000 meters (16,000 feet).[67] This valley has no natural drainage outlet for the waters that flow from the mountainsides, making the city vulnerable to flooding. Drainage was engineered through the use of canals and tunnels starting in the 17th century.[65][67]

Mexico City primarily rests on what was Lake Texcoco.[65] Seismic activity is frequent there.[68] Lake Texcoco was drained starting from the 17th century. Although none of the lake waters remain, the city rests on the lake bed's heavily saturated clay. This soft base is collapsing due to the over-extraction of groundwater, called groundwater-related subsidence. Since the beginning of the 20th century the city has sunk as much as nine meters (30 feet) in some areas. This sinking is causing problems with runoff and wastewater management, leading to flooding problems, especially during the summer.[67][68][69] The entire lake bed is now paved over and most of the city's remaining forested areas lie in the southern boroughs of Milpa Alta, Tlalpan and Xochimilco.[68]

| Mexico City geophysical maps | |||

|

|

| |

| Topography | Hydrology | Climate patterns | |

Climate

Mexico City has a subtropical highland climate (Köppen climate classification Cwb), due to its tropical location but high elevation. The lower region of the valley receives less rainfall than the upper regions of the south; the lower boroughs of Iztapalapa, Iztacalco, Venustiano Carranza and the east portion of Gustavo A. Madero are usually drier and warmer than the upper southern boroughs of Tlalpan and Milpa Alta, a mountainous region of pine and oak trees known as the range of Ajusco.

The average annual temperature varies from 12 to 16 °C (54 to 61 °F), depending on the altitude of the borough. The temperature is rarely below 3 °C (37 °F) or above 30 °C (86 °F).[71] At the Tacubaya observatory, the lowest temperature ever registered was −4.4 °C (24 °F) on 13 February 1960, and the highest temperature on record was 33.9 °C (93 °F) on 9 May 1998.[72]

Overall precipitation is heavily concentrated in the summer months, and includes dense hail.

Snow falls in the city very rarely, although somewhat more often in nearby mountain tops. Throughout its history, the Central Valley of Mexico was accustomed to having several snowfalls per decade (including a period between 1878 and 1895 in which every single year—except 1880—recorded snowfalls[73]) mostly lake-effect snow. The effects of the draining of Lake Texcoco and global warming have greatly reduced snowfalls after the snow flurries of 12 February 1907.[74] Since 1908, snow has only fallen three times, snow on 14 February 1920;[75] snow flurries on 14 March 1940;[76] and on 12 January 1967, when 8 centimetres (3 in) of snow fell on the city, the most on record.[77] The 1967 snowstorm coincided with the operation of Deep Drainage System that resulted in the total draining of what was left of Lake Texcoco.[73][78] After the disappearance of Lake Texcoco, snow has never fallen again over Mexico City.[73]

The region of the Valley of Mexico receives anti-cyclonic systems. The weak winds of these systems do not allow for the dispersion, outside the basin, of the air pollutants which are produced by the 50,000 industries and 4 million vehicles operating in and around the metropolitan area.[79]

The area receives about 820 millimeters (32 in) of annual rainfall, which is concentrated from May through October with little or no precipitation the remainder of the year.[67] The area has two main seasons. The wet humid summer runs from May to October when winds bring in tropical moisture from the sea, the wettest month being July. The cool sunny winter runs from November to April, when the air is relatively drier, the driest month being December. This season is subdivided into a cold winter period and a warm spring period. The cold period spans from November to February, when polar air masses push down from the north and keep the air fairly dry. The warm period extends from March to May when subtropical winds again dominate but do not yet carry enough moisture for rain to form.[80]

| Climate data for Mexico City (Tacubaya), 1981–2000 normals, extremes 1921-2000 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.2 (82.8) |

29.3 (84.7) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

30.0 (86.0) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.9 (84.0) |

29.3 (84.7) |

28.0 (82.4) |

33.9 (93.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 21.7 (71.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

25.3 (77.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.6 (58.3) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.3 (64.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.4 (45.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.3 (54.1) |

13.2 (55.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

12.7 (54.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.1 (24.6) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

5.3 (41.5) |

6 (43) |

1.6 (34.9) |

0 (32) |

−3 (27) |

−3 (27) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 7.6 (0.30) |

7.0 (0.28) |

8.9 (0.35) |

22.5 (0.89) |

66.5 (2.62) |

140.0 (5.51) |

189.5 (7.46) |

171.2 (6.74) |

139.8 (5.50) |

72.4 (2.85) |

12.6 (0.50) |

8.2 (0.32) |

846.1 (33.31) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.2 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 6.8 | 12.9 | 18.7 | 23.2 | 20.9 | 18.2 | 9.6 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 124.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 51 | 47 | 41 | 43 | 51 | 63 | 69 | 69 | 70 | 64 | 57 | 54 | 56 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 240 | 234 | 268 | 232 | 225 | 183 | 176 | 176 | 157 | 194 | 232 | 236 | 2,555 |

| Source: Colegio de Postgraduados (extremes)[81] Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (normals, precipitation and sunshine hours 1981–2000)[82] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Mexico City (Tacubaya), 1961–1990 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.0 (82.4) |

33.8 (92.8) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.0 (91.4) |

35.0 (95.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

30.3 (86.5) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.0 (91.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.3 (84.7) |

35.0 (95.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 21.3 (70.3) |

22.9 (73.2) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

24.7 (76.5) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.3 (70.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.4 (56.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

17.4 (63.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

16.4 (61.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

14.9 (58.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) |

7.4 (45.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

11.8 (53.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

10.4 (50.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.4 (29.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

3.7 (38.7) |

7.0 (44.6) |

3.0 (37.4) |

2.0 (35.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

1.9 (35.4) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 9 (0.4) |

9 (0.4) |

13 (0.5) |

27 (1.1) |

58 (2.3) |

157 (6.2) |

183 (7.2) |

173 (6.8) |

144 (5.7) |

61 (2.4) |

6 (0.2) |

8 (0.3) |

848 (33.5) |

| Average rainy days | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 13 | 19 | 24 | 22 | 19 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 130 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 55.5 | 53.5 | 51.5 | 52.5 | 55 | 59 | 64 | 67.5 | 65 | 62 | 57 | 58 | 58.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 208.2 | 212.1 | 228.6 | 209.4 | 196.9 | 152.6 | 144.2 | 158.4 | 139.1 | 177.0 | 198.5 | 186.5 | 2,211.5 |

| Source 1: NOAA[83] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climatebase.ru (extremes)[84] | |||||||||||||

Environment

Originally much of the valley lay beneath the waters of Lake Texcoco, a system of interconnected salt and freshwater lakes. The Aztecs built dikes to separate the fresh water used to raise crops in chinampas and to prevent recurrent floods. These dikes were destroyed during the siege of Tenochtitlan, and during colonial times the Spanish regularly drained the lake to prevent floods. Only a small section of the original lake remains, located outside Mexico City, in the municipality of Atenco, State of Mexico.

Architects Teodoro González de León and Alberto Kalach along with a group of Mexican urbanists, engineers and biologists have developed the project plan for Recovering the City of Lakes. If approved by the government the project will contribute to the supply of water from natural sources to the Valley of Mexico, the creation of new natural spaces, a great improvement in air quality, and greater population establishment planning.

Pollution

By the 1990s Mexico City had become infamous as one of the world's most polluted cities; however, the city has become a model for drastically lowering pollution levels. By 2014 carbon monoxide pollution had dropped drastically, while levels of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide were nearly three times lower than in 1992. The levels of signature pollutants in Mexico City are similar to those of Los Angeles.[85] Despite the cleanup, the metropolitan area is still the most ozone-polluted part of the country, with ozone levels 2.5 times beyond WHO-defined safe limits.[86]

To clean up pollution, the federal and local governments implemented numerous plans including the constant monitoring and reporting of environmental conditions, such as ozone and nitrogen oxides.[87] When the levels of these two pollutants reached critical levels, contingency actions were implemented which included closing factories, changing school hours, and extending the A day without a car program to two days of the week.[87] The government also instituted industrial technology improvements, a strict biannual vehicle emission inspection and the reformulation of gasoline and diesel fuels.[87] The introduction of Metrobús bus rapid transit and the Ecobici bike-sharing were among efforts to encourage alternate, greener forms of transportation.[86]

Politics

Political structure

The Acta Constitutiva de la Federación of 31 January 1824, and the Federal Constitution of 4 October 1824,[88] fixed the political and administrative organization of the United Mexican States after the Mexican War of Independence. In addition, Section XXVIII of Article 50 gave the new Congress the right to choose where the federal government would be located. This location would then be appropriated as federal land, with the federal government acting as the local authority. The two main candidates to become the capital were Mexico City and Querétaro.[89]

Due in large part to the persuasion of representative Servando Teresa de Mier, Mexico City was chosen because it was the center of the country's population and history, even though Querétaro was closer to the center geographically. The choice was official on 18 November 1824, and Congress delineated a surface area of two leagues square (8,800 acres) centered on the Zocalo. This area was then separated from the State of Mexico, forcing that state's government to move from the Palace of the Inquisition (now Museum of Mexican Medicine) in the city to Texcoco. This area did not include the population centers of the towns of Coyoacán, Xochimilco, Mexicaltzingo and Tlalpan, all of which remained as part of the State of Mexico.[90]

In 1854 president Antonio López de Santa Anna enlarged the area of Mexico City almost eightfold from the original 220 to 1,700 km2 (80 to 660 sq mi), annexing the rural and mountainous areas to secure the strategic mountain passes to the south and southwest to protect the city in event of a foreign invasion. (The Mexican–American War had just been fought.) The last changes to the limits of Mexico City were made between 1898 and 1902, reducing the area to the current 1,479 km2 (571 sq mi) by adjusting the southern border with the state of Morelos. By that time, the total number of municipalities within Mexico City was twenty-two.

While Mexico City was ruled by the federal government through an appointed governor, the municipalities within it were autonomous, and this duality of powers created tension between the municipalities and the federal government for more than a century. In 1903, Porfirio Díaz largely reduced the powers of the municipalities within the Federal District. Eventually, in December 1928, the federal government decided to abolish all the municipalities of the Federal District. In place of the municipalities, the Federal District was divided into one "Central Department" and 13 delegaciones (boroughs) administered directly by the government of the Federal District. The Central Department was integrated by the former municipalities of Mexico City, Tacuba, Tacubaya and Mixcoac.

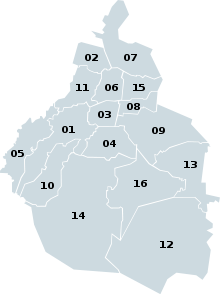

In 1941, the General Anaya borough was merged with the Central Department, which was then renamed "Mexico City" (thus reviving the name but not the autonomous municipality). From 1941 to 1970, the Federal District comprised twelve delegaciones and Mexico City. In 1970, Mexico City was split into four different delegaciones: Cuauhtémoc, Miguel Hidalgo, Venustiano Carranza and Benito Juárez, increasing the number of delegaciones to 16. Since then, the whole Federal District, whose delegaciones had by then almost formed a single urban area, began to be considered de facto a synonym of Mexico City.[91]

The lack of a de jure stipulation left a legal vacuum that led to a number of sterile discussions about whether one concept had engulfed the other or if the latter had ceased to exist altogether. In 1993, the situation was solved by an amendment to the 44th article of the Constitution of Mexico; Mexico City and the Federal District were stated to be the same entity. The amendment was later introduced into the second article of the Statute of Government of the Federal District.[91]

On 29 January 2016, Mexico City ceased to be the Federal District (Spanish: Distrito Federal or D.F.), and was officially renamed "Ciudad de México" (or "CDMX").[26] On that date, Mexico City began a transition to become the country's 32nd federal entity, giving it a level of autonomy comparable to that of a state. It will have its own constitution and its legislature, and its delegaciones will now be headed by mayors.[26] Because of a clause in the Mexican Constitution, however, as it is the seat of the powers of the federation, it can never become a state, or the capital of the country has to be relocated elsewhere.[28]

Mexico City, being the seat of the powers of the Union, belongs not to any particular state but to all of them. Therefore, the president, representing the federation, used to designate the head of government of the national capital (today the head of the government of Mexico City), sometimes called outside Mexico as the "Mayor" of Mexico City. In the 1980s, the dramatic increase in population of the previous decades, the inherent political inconsistencies of the system, and dissatisfaction with the inadequate response of the federal government after the 1985 earthquake made residents begin to request political and administrative autonomy to manage their local affairs.

In response to the demands, Mexico City received a greater degree of autonomy, with the 1987 elaboration the first Statute of Government (Estatuto de Gobierno) and the creation of an assembly of representatives. In the 1990s, this autonomy was further expanded, and since 1997, residents can directly elect the head of government to Mexico City and the representatives of a unicameral Legislative Assembly, which succeeded the previous assembly, by popular vote.

The first elected head of government was Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas. He resigned in 1999 to run in the 2000 presidential elections and designated Rosario Robles to succeed him, who became the first woman, elected or otherwise, to govern Mexico City. In 2000, Andrés Manuel López Obrador was elected, and he resigned in 2005 to run in the 2006 presidential elections; Alejandro Encinas was designated by the Legislative Assembly to finish the term. In 2006, Marcelo Ebrard was elected to serve until 2012.

The city has a Statute of Government, and as of its ratification on 31 January 2017, a constitution,[92][93] similar to the states of the Union. As part of the recent changes in autonomy, the budget is administered locally; it is proposed by the head of government and approved by the Legislative Assembly. Nonetheless, it is the Congress of the Union that sets the ceiling to internal and external public debt issued by the city government.[94]

According to the 44th article of the Mexican Constitution, if the powers of the Union move to another city, Mexico City would become a new state, the "State of the Valley of Mexico", with the new limits set by the Congress of the Union.

Elections and government

In 2012, elections were held for the post of head of government and the representatives of the Legislative Assembly. Heads of government are elected for a six-year period without the possibility of re-election. Traditionally, the position has been considered as the second most important executive office in the country.[95]

The Legislative Assembly of Mexico City is formed, as it is the case for state legislatures in Mexico, by both single-seat and proportional seats, making it a system of parallel voting. Mexico City is divided into 40 electoral constituencies of similar population which elect one representative by the plurality voting system, locally called "uninominal deputies". Mexico City, as a whole, is a single constituency for the parallel election of 26 representatives, elected by proportional representation, with open-party lists, locally called "plurinominal deputies".

Even though proportionality is supposed to prevent a party from being overrepresented, several restrictions apply in the assignation of the seats. No party can have more than 63% of all seats, both uninominal and plurinominal. In the 2006 elections, the PRD got the absolute majority in the direct uninominal elections, securing 34 of the 40 FPP seats. As such, the PRD was not assigned any plurinominal seat to comply with the law that prevents over-representation. The overall composition of the Legislative Assembly is:

| Political party | FPP | PR | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 4 | 22 | |

| 14 | 7 | 21 | |

| 5 | 5 | 10 | |

| 3 | 6 | 9 | |

| 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 40 | 26 | 66 |

The politics pursued by the administrations of heads of government in Mexico City since the second half of the 20th century have usually been more liberal than those of the rest of the country, whether with the support of the federal government, as was the case with the approval of several comprehensive environmental laws in the 1980s, or by laws that were since approved by the Legislative Assembly. The Legislative Assembly expanded provisions on abortions, becoming the first federal entity to expand abortion in Mexico beyond cases of rape and economic reasons, to permit it at the choice of the mother before the 12th week of pregnancy.[96] In December 2009, the then Federal District became the first city in Latin America and one of very few in the world to legalize same-sex marriage.

Boroughs and neighborhoods

For administrative purposes, the city is divided into 16 alcadias, or councils (formerly delegaciones). While they are not fully equivalent to municipalities, the boroughs have gained significant autonomy, and since 2000, their heads of government have been elected directly by plurality (they had been appointed by the Head of Government). Since Mexico City is organized entirely as a Federal District, most of the city services are provided or organized by the city government, not by the boroughs themselves; in the constituent states, such services would be provided by the municipalities. The boroughs of Mexico City with their 2010 populations are:[97]

|

1. Álvaro Obregón (pop. 727,034) |

9. Iztapalapa (pop. 1,815,786) |

The boroughs are composed of hundreds of colonias, or neighborhoods, which have no jurisdictional autonomy or representation. The Historic Center, in the borough of Cuauhtémoc, is the oldest part of the city (along with some other, formerly separate colonial towns such as Coyoacán and San Ángel), some of the buildings dating back to the 16th century. Other well-known central neighborhoods include Condesa, known for its Art Deco architecture and its restaurant scene; Colonia Roma, a beaux arts neighborhood and artistic and culinary hot-spot, the Zona Rosa, formerly the center of nightlife and restaurants, now reborn as the center of the LGBT and Korean-Mexican communities; and Tepito and La Lagunilla, known for their local working-class folklore and large flea markets. Santa María la Ribera and San Rafael are the latest neighborhoods of magnificent Porfiriato architecture seeing the first signs of gentrification.

West of the Historic Center (Centro Histórico) along Paseo de la Reforma are many of the city's wealthiest neighborhoods such as Polanco, Lomas de Chapultepec, Bosques de las Lomas, Santa Fe, and (in the State of Mexico) Interlomas, which are also the city's most important areas of class A office space, corporate headquarters, skyscrapers, and shopping malls. Nevertheless, some areas of lower-income colonias are right next to rich neighborhoods, particularly in the case of Santa Fe.

The south of the city is home to some other high-income neighborhoods such as Colonia del Valle and Jardines del Pedregal and the formerly separate colonial towns of Coyoacán, San Ángel, and San Jerónimo. Along Avenida Insurgentes from Paseo de la Reforma, near the center, south past the World Trade Center and UNAM university toward the Periférico ring road, is another important corridor of corporate office space. The far-southern boroughs of Xochimilco and Tláhuac have a significant rural population, with Milpa Alta being entirely rural.

East of the center are mostly lower-income areas with some middle-class neighborhoods such as Jardín Balbuena. Urban sprawl continues further east for many miles into the State of Mexico, including Ciudad Nezahualcoyotl, now increasingly middle class but once full of informal settlements. Such slums are still found on the eastern edges of the metropolitan area in the Chalco area.

North of the Historic Center, Azcapotzalco and Gustavo A. Madero have important industrial centers and neighborhoods that range from established middle-class colonias such as Claveria and Lindavista to huge low-income housing areas that share hillsides with adjacent municipalities in the State of Mexico. In recent years, much of northern Mexico City's industry has moved to nearby municipalities in the State of Mexico. Northwest of Mexico City itself is Ciudad Satélite, a vast middle-class to upper-middle-class residential and business area.

The Human Development Index report of 2005[98] shows that there were three boroughs with a very high Human Development Index, 12 with a high HDI value (9 above .85), and one with a medium HDI value (almost high). Benito Juárez borough had the highest HDI of the country (0.9510) followed by Miguel Hidalgo, which came up fourth nationally with an HDI of (0.9189), and Coyoacán was fifth nationally, with an HDI of (0.9169). Cuajimalpa (15th), Cuauhtémoc (23rd), and Azcapotzalco (25th) also had very high values of 0.8994, 0.8922, and 0.8915, respectively.

In contrast, the boroughs of Xochimilco (172nd), Tláhuac (177th), and Iztapalapa (183rd) presented the lowest HDI values of Mexico City, with values of 0.8481, 0.8473, and 0.8464, respectively, which are still in the global high-HDI range. The only borough that did not have a high HDI was that of rural Milpa Alta, which had a "medium" HDI of 0.7984, far below those of all the other boroughs (627th nationally, the rest being in the top 200). Mexico City's HDI for the 2005 report was 0.9012 (very high), and its 2010 value of 0.9225 (very high), or (by newer methodology) 0.8307, was Mexico's highest.

Metropolitan area

Greater Mexico City is formed by Mexico City, 60 municipalities from the State of Mexico and one from the state of Hidalgo. Greater Mexico City is the largest metropolitan area in Mexico and the area with the highest population density. As of 2009, 21,163,226 people live in this urban agglomeration, of which 8,841,916 live in Mexico City proper.[17] In terms of population, the biggest municipalities that are part of Greater Mexico City (excluding Mexico City proper) are:[99]

- Ecatepec de Morelos (pop. 1,658,806)

- Nezahualcóyotl (pop. 1,109,363)

- Naucalpan (pop. 833,782)

- Tlalnepantla de Baz (pop. 664,160)

- Chimalhuacán (pop. 602,079)

- Cuautitlán Izcalli (pop. 532,973)

- Atizapan de Zaragoza (pop. 489,775)

- Ixtapaluca (pop. 467,630)

The above municipalities are located in the state of Mexico but are part of the Greater Mexico City area. Approximately 75% (10 million) of the state of México's population live in municipalities that are part of Greater Mexico City's conurbation.

Greater Mexico City was the fastest growing metropolitan area in the country until the late 1980s. Since then, and through a policy of decentralization in order to reduce the environmental pollutants of the growing conurbation, the annual rate of growth of the agglomeration has decreased, and it is lower than that of the other four largest metropolitan areas (namely Greater Guadalajara, Greater Monterrey, Greater Puebla and Greater Toluca) even though it is still positive.[100]

The net migration rate of Mexico City proper from 1995 to 2000 was negative,[101] which implies that residents are moving to the suburbs of the metropolitan area, or to other states of Mexico. In addition, some inner suburbs are losing population to outer suburbs, indicating the continuing expansion of Greater Mexico City.

Law enforcement

The Secretariat of Public Security of Mexico City (Secretaría de Seguridad Pública de la Ciudad de México – SSP) manages a combined force of over 90,000 officers in Mexico City. The SSP is charged with maintaining public order and safety in the heart of Mexico City. The historic district is also roamed by tourist police, aiming to orient and serve tourists. These horse-mounted agents dress in traditional uniforms.

The investigative Judicial Police of Mexico City (Policía Judicial de la Ciudad de México – PJCDMX) is organized under the Office of the Attorney General of Mexico City (the Procuraduría General de Justicia de la Ciudad de México). The PGJCDMX maintains 16 precincts (delegaciones) with an estimated 3,500 judicial police, 1,100 investigating agents for prosecuting attorneys (agentes del ministerio público), and nearly 1,000 criminology experts or specialists (peritos).

Between 2000 and 2004 an average of 478 crimes were reported each day in Mexico City; however, the actual crime rate is thought to be much higher "since most people are reluctant to report crime".[102] Under policies enacted by Mayor Marcelo Ebrard between 2009 and 2011, Mexico City underwent a major security upgrade with violent and petty crime rates both falling significantly despite the rise in violent crime in other parts of the country. Some of the policies enacted included the installation of 11,000 security cameras around the city and a very large expansion of the police force. Mexico City has one of the world's highest police officer-to-resident ratios, with one uniformed officer per 100 citizens.[103] Since 1997 the prison population has increased by more than 500%.[104] Political scientist Markus-Michael Müller argues that mostly informal street vendors are hit by these measures. He sees punishment "related to the growing politicisation of security and crime issues and the resulting criminalisation of the people living at the margins of urban society, in particular those who work in the city's informal economy."[104]

Femicides and violence against women

In 2016, the incidence of femicides was 3.2 per 100 000 inhabitants, the national average being 4.2.[105] A 2015 city government report found that two of three women over the age of 15 in the capital suffered some form of violence.[106] In addition to street harassment, one of the places where women in Mexico City live in violence is public transport. Annually the Metro of Mexico City receives 300 complaints of sexual harassment.[107]

While the violence against women in Mexico city is rising, there is still a large number of incidents of kidnappings and killings that go undetected and unreported due to the corruption in the police department.

Health

Mexico City is home to some of the best private hospitals in the country, including Hospital Ángeles, Hospital ABC and Médica Sur. The national public healthcare institution for private-sector employees, IMSS, has its largest facilities in Mexico City—including the National Medical Center and the La Raza Medical Center—and has an annual budget of over 6 billion pesos. The IMSS and other public health institutions, including the ISSSTE (Public Sector Employees' Social Security Institute) and the National Health Ministry (SSA) maintain large specialty facilities in the city. These include the National Institutes of Cardiology, Nutrition, Psychiatry, Oncology, Pediatrics, Rehabilitation, among others.

The World Bank has sponsored a project to curb air pollution through public transport improvements and the Mexican government has started shutting down polluting factories. They have phased out diesel buses and mandated new emission controls on new cars; since 1993 all new cars must be fitted with a catalytic converter, which reduces the emissions released. Trucks must use only liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). Also construction of an underground rail system was begun in 1968 in order to help curb air pollution problems and alleviate traffic congestion. It has over 201 km (125 mi) of track and carries over 5 million people every day. Fees are kept low to encourage use of the system and during rush hours the crush is so great, that authorities have reserved a special carriage specifically for women. Due to these initiatives and others, the air quality in Mexico City has begun to improve; it is cleaner than it was in 1991, when the air quality was declared to be a public health risk for 355 days of the year.

Economy

Mexico City is one of the most important economic hubs in Latin America. The city proper produces 15.8% of the country's gross domestic product.[108] According to a study conducted by PwC, Mexico City had a GDP of $390 billion, ranking it as the eighth richest city in the world and the richest in Latin America.[109] Mexico City alone would rank as the 30th largest economy in the world.[110] Mexico City is the greatest contributor to the country's industrial GDP (15.8%) and also the greatest contributor to the country's GDP in the service sector (25.3%). Due to the limited non-urbanized space at the south—most of which is protected through environmental laws—the contribution of Mexico City in agriculture is the smallest of all federal entities in the country.[108] Mexico City has one of the world's fastest-growing economies and its GDP is set to double from 2008 to 2020.[111]

In 2002, Mexico City had a Human Development Index score of 0.915,[112] identical to that of South Korea.

The top twelve percent of GDP per capita holders in the city had a mean disposable income of US$98,517 in 2007. The high spending power of Mexico City inhabitants makes the city attractive for companies offering prestige and luxury goods.

The economic reforms of President Carlos Salinas de Gortari had a tremendous effect on the city, as a number of businesses, including banks and airlines, were privatized. He also signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). This led to decentralization[111] and a shift in Mexico City's economic base, from manufacturing to services, as most factories moved away to either the State of Mexico, or more commonly to the northern border. By contrast, corporate office buildings set their base in the city.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 3,365,081 | — |

| 1960 | 5,479,184 | +62.8% |

| 1970 | 8,830,947 | +61.2% |

| 1980 | 13,027,620 | +47.5% |

| 1990 | 15,642,318 | +20.1% |

| 2000 | 18,457,027 | +18.0% |

| 2010 | 20,136,681 | +9.1% |

| 2019 | 21,671,908 | +7.6% |

| for Mexico City Agglomeration:[114] | ||

Historically, and since Pre-Columbian times, the Valley of Anahuac has been one of the most densely populated areas in Mexico. When the Federal District was created in 1824, the urban area of Mexico City extended approximately to the area of today's Cuauhtémoc borough. At the beginning of the 20th century, the elites began migrating to the south and west and soon the small towns of Mixcoac and San Ángel were incorporated by the growing conurbation. According to the 1921 census, 54.78% of the city's population was considered Mestizo (Indigenous mixed with European), 22.79% considered European, and 18.74% considered Indigenous.[115] This was the last Mexican Census which asked people to self-identify with a heritage other than Amerindian. However, the census had the particularity that, unlike racial/ethnic census in other countries, it was focused in the perception of cultural heritage rather than in a racial perception, leading to a good number of white people to identify with "Mixed heritage" due to cultural influence.[116] In 1921, Mexico City had less than one million inhabitants.

Up to the 1990s, the Federal District was the most populous federal entity in Mexico, but since then, its population has remained stable at around 8.7 million. The growth of the city has extended beyond the limits of the city to 59 municipalities of the State of Mexico and 1 in the state of Hidalgo.[117] With a population of approximately 19.8 million inhabitants (2008),[118] it is one of the most populous conurbations in the world. Nonetheless, the annual rate of growth of the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City is much lower than that of other large urban agglomerations in Mexico,[100] a phenomenon most likely attributable to the environmental policy of decentralization. The net migration rate of Mexico City from 1995 to 2000 was negative.[119]

Representing around 18.74% of the city's population, indigenous peoples from different areas of Mexico have migrated to the capital in search of better economic opportunities. Nahuatl, Otomi, Mixtec, Zapotec and Mazahua are the indigenous languages with the greatest number of speakers in Mexico City.[120]

Nationality

_03.jpg)

On the other hand, Mexico City is also home to large communities of expatriates and immigrants, most notably from the rest of North America (U.S. and Canada), from South America (mainly from Argentina and Colombia, but also from Brazil, Chile, Uruguay and Venezuela), from Central America and the Caribbean (mainly from Cuba, Guatemala, El Salvador, Haiti and Honduras); from Europe (mainly from Spain, Germany and Switzerland, but also from Czech Republic, Hungary, France, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland and Romania),[121][122] from the Middle East (mainly from Egypt, Lebanon and Syria);[123] and recently from Asia-Pacific (mainly from China, Japan, Pakistan, India and South Korea).[124] Historically since the era of New Spain, many Filipinos settled in the city and have become integrated in Mexican society. While no official figures have been reported, population estimates of each of these communities are quite significant.

Mexico City is home to the largest population of U.S. Americans living outside the United States. Estimates are as high as 700,000 U.S. Americans living in Mexico City, while in 1999 the U.S. Bureau of Consular Affairs estimated over 440,000 Americans lived in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area.[125][126]

Religion

The majority (82%) of the residents in Mexico City are Roman Catholic, slightly lower than the 2010 census national percentage of 87%, though it has been decreasing over the last decades.[127] Many other religions and philosophies are also practiced in the city: many different types of Protestant groups, different types of Jewish communities, Buddhist, Islamic and other spiritual and philosophical groups. There are also growing numbers of irreligious people, whether agnostic or atheist. The patron saint of Mexico City is Saint Philip of Jesus, a Mexican Catholic missionary who became one of the Twenty-six Martyrs of Japan.[128]

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mexico is the largest archdiocese in the world.[129] There are two Roman Catholic cathedrals in the city, the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral and the Iztapalapa Cathedral, and three former Catholic churches who are now the cathedrals of other rites, the San José de Gracia Cathedral (Anglican church), the Porta Coeli Cathedral (Melkite Greek Catholic church) and the Valvanera Cathedral (Maronite church).

Culture

Tourism

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mexico City. |

Mexico City is a destination for many foreign tourists. The Historic center of Mexico City (Centro Histórico) and the "floating gardens" of Xochimilco in the southern borough have been declared World Heritage Sites by UNESCO. Landmarks in the Historic Center include the Plaza de la Constitución (Zócalo), the main central square with its epoch-contrasting Spanish-era Metropolitan Cathedral and National Palace, ancient Aztec temple ruins Templo Mayor ("Major Temple") and modern structures, all within a few steps of one another. (The Templo Mayor was discovered in 1978 while workers were digging to place underground electric cables).

The most recognizable icon of Mexico City is the golden Angel of Independence on the wide, elegant avenue Paseo de la Reforma, modeled by the order of the Emperor Maximilian of Mexico after the Champs-Élysées in Paris. This avenue was designed over the Americas' oldest known major roadway in the 19th century to connect the National Palace (seat of government) with the Castle of Chapultepec, the imperial residence. Today, this avenue is an important financial district in which the Mexican Stock Exchange and several corporate headquarters are located. Another important avenue is the Avenida de los Insurgentes, which extends 28.8 km (17.9 mi) and is one of the longest single avenues in the world.

Chapultepec Park houses the Chapultepec Castle, now a museum on a hill that overlooks the park and its numerous museums, monuments and the national zoo and the National Museum of Anthropology (which houses the Aztec Calendar Stone). Another piece of architecture is the Palacio de Bellas Artes, a white marble theatre/museum whose weight is such that it has gradually been sinking into the soft ground below. Its construction began during the presidency of Porfirio Díaz and ended in 1934, after being interrupted by the Mexican Revolution in the 1920s. The Plaza de las Tres Culturas, in this square are located the College of Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, that is the first and oldest European school of higher learning in the Americas,[130] and the archaeological site of the city-state of Tlatelolco, and the shrine and Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe are also important sites. There is a double-decker bus, known as the "Turibus", that circles most of these sites, and has timed audio describing the sites in multiple languages as they are passed.

In addition, according to the Secretariat of Tourism, the city has about 170 museums—is among the top ten of cities in the world with highest number of museums[131][132]—over 100 art galleries, and some 30 concert halls, all of which maintain a constant cultural activity during the whole year. It has either the third or fourth-highest number of theatres in the world after New York, London and perhaps Toronto. Many areas (e.g. Palacio Nacional and the National Institute of Cardiology) have murals painted by Diego Rivera. He and his wife Frida Kahlo lived in Coyoacán, where several of their homes, studios, and art collections are open to the public. The house where Leon Trotsky was initially granted asylum and finally murdered in 1940 is also in Coyoacán.

In addition, there are several haciendas that are now restaurants, such as the San Ángel Inn, the Hacienda de Tlalpan, Hacienda de Cortés and the Hacienda de los Morales.

Art

Having been capital of a vast pre-Hispanic empire, and also the capital of richest viceroyalty within the Spanish Empire (ruling over a vast territory in the Americas and Spanish West Indies), and, finally, the capital of the United Mexican States, Mexico City has a rich history of artistic expression. Since the mesoamerican pre-Classical period the inhabitants of the settlements around Lake Texcoco produced many works of art and complex craftsmanship, some of which are today displayed at the world-renowned National Museum of Anthropology and the Templo Mayor museum. While many pieces of pottery and stone-engraving have survived, the great majority of the Amerindian iconography was destroyed during the Conquest of Mexico.

Much of the early colonial art stemmed from the codices (Aztec illustrated books), aiming to recover and preserve some Aztec and other Amerindian iconography and history. From then, artistic expressions in Mexico were mostly religious in theme. The Metropolitan Cathedral still displays works by Juan de Rojas, Juan Correa and an oil painting whose authorship has been attributed to Murillo. Secular works of art of this period include the equestrian sculpture of Charles IV of Spain, locally known as El Caballito ("The little horse"). This piece, in bronze, was the work of Manuel Tolsá and it has been placed at the Plaza Tolsá, in front of the Palacio de Mineria (Mining Palace). Directly in front of this building is the Museo Nacional de Arte (Munal) (the National Museum of Art).

During the 19th century, an important producer of art was the Academia de San Carlos (San Carlos Art Academy), founded during colonial times, and which later became the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (the National School of Arts) including painting, sculpture and graphic design, one of UNAM's art schools. Many of the works produced by the students and faculty of that time are now displayed in the Museo Nacional de San Carlos (National Museum of San Carlos). One of the students, José María Velasco, is considered one of the greatest Mexican landscape painters of the 19th century. Porfirio Díaz's regime sponsored arts, especially those that followed the French school. Popular arts in the form of cartoons and illustrations flourished, e.g. those of José Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Manilla. The permanent collection of the San Carlos Museum also includes paintings by European masters such as Rembrandt, Velázquez, Murillo, and Rubens.

After the Mexican Revolution, an avant-garde artistic movement originated in Mexico City: muralism. Many of the works of muralists José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera are displayed in numerous buildings in the city, most notably at the National Palace and the Palacio de Bellas Artes. Frida Kahlo, wife of Rivera, with a strong nationalist expression, was also one of the most renowned of Mexican painters. Her house has become a museum that displays many of her works.[133]

The former home of Rivera muse Dolores Olmedo houses the namesake museum. The facility is in Xochimilco borough in southern Mexico City and includes several buildings surrounded by sprawling manicured lawns. It houses a large collection of Rivera and Kahlo paintings and drawings, as well as living Xoloizcuintles (Mexican Hairless Dog). It also regularly hosts small but important temporary exhibits of classical and modern art (e.g. Venetian Masters and Contemporary New York artists).

During the 20th century, many artists immigrated to Mexico City from different regions of Mexico, such as Leopoldo Méndez, an engraver from Veracruz, who supported the creation of the socialist Taller de la Gráfica Popular (Popular Graphics Workshop), designed to help blue-collar workers find a venue to express their art. Other painters came from abroad, such as Catalan painter Remedios Varo and other Spanish and Jewish exiles. It was in the second half of the 20th century that the artistic movement began to drift apart from the Revolutionary theme. José Luis Cuevas opted for a modernist style in contrast to the muralist movement associated with social politics.

Museums

Mexico City has numerous museums dedicated to art, including Mexican colonial, modern and contemporary art, and international art. The Museo Tamayo was opened in the mid-1980s to house the collection of international contemporary art donated by famed Mexican (born in the state of Oaxaca) painter Rufino Tamayo. The collection includes pieces by Picasso, Klee, Kandinsky, Warhol and many others, though most of the collection is stored while visiting exhibits are shown. The Museo de Arte Moderno (Museum of Modern Art) is a repository of Mexican artists from the 20th century, including Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros, Kahlo, Gerzso, Carrington, Tamayo, among others, and also regularly hosts temporary exhibits of international modern art. In southern Mexico City, the Museo Carrillo Gil (Carrillo Gil Museum) showcases avant-garde artists, as does the University Museum/Contemporary Art (Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo – or MUAC), designed by famed Mexican architect Teodoro González de León, inaugurated in late 2008.

The Museo Soumaya, named after the wife of Mexican magnate Carlos Slim, has the largest private collection of original Rodin sculptures outside Paris. It also has a large collection of Dalí sculptures, and recently began showing pieces in its masters collection including El Greco, Velázquez, Picasso and Canaletto. The museum inaugurated a new futuristic-design facility in 2011 just north of Polanco, while maintaining a smaller facility in Plaza de Loreto in southern Mexico City. The Colección Júmex is a contemporary art museum located on the sprawling grounds of the Jumex juice company in the northern industrial suburb of Ecatepec. It is said to have the largest private contemporary art collection in Latin America and hosts pieces from its permanent collection as well as traveling exhibits by leading contemporary artists. The new Museo Júmex in Nuevo Polanco was slated to open in November 2013. The Museo de San Ildefonso, housed in the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso in Mexico City's historic downtown district is a 17th-century colonnaded palace housing an art museum that regularly hosts world-class exhibits of Mexican and international art. Recent exhibits have included those on David LaChapelle, Antony Gormley and Ron Mueck. The National Museum of Art (Museo Nacional de Arte) is also located in a former palace in the historic center. It houses a large collection of pieces by all major Mexican artists of the last 400 years and also hosts visiting exhibits.

Jack Kerouac, the noted American author, spent extended periods of time in the city, and wrote his masterpiece volume of poetry Mexico City Blues here. Another American author, William S. Burroughs, also lived in the Colonia Roma neighborhood of the city for some time. It was here that he accidentally shot his wife.

Most of Mexico City's more than 150 museums can be visited from Tuesday to Sunday from 10 am to 5 pm, although some of them have extended schedules, such as the Museum of Anthropology and History, which is open to 7 pm. In addition to this, entrance to most museums are free on Sunday. In some cases a modest fee may be charged.[134]

Another major addition to the city's museum scene is the Museum of Remembrance and Tolerance (Museo de la Memoria y Tolerancia), inaugurated in early 2011. The brainchild of two young Mexican women as a Holocaust museum, the idea morphed into a unique museum dedicated to showcasing all major historical events of discrimination and genocide. Permanent exhibits include those on the Holocaust and other large-scale atrocities. It also houses temporary exhibits; one on Tibet was inaugurated by the Dalai Lama in September 2011.[135]

Music, theater and entertainment

Mexico City is home to a number of orchestras offering season programs. These include the Mexico City Philharmonic,[136] which performs at the Sala Ollin Yoliztli; the National Symphony Orchestra, whose home base is the Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of the Fine Arts), a masterpiece of art nouveau and art decó styles; the Philharmonic Orchestra of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (OFUNAM),[137] and the Minería Symphony Orchestra,[138] both of which perform at the Sala Nezahualcóyotl, which was the first wrap-around concert hall of the world's western hemisphere when inaugurated in 1976. There are also many smaller ensembles that enrich the city's musical scene, including the Carlos Chávez Youth Symphony, the Cuarteto Latinoamericano, the New World Orchestra (Orquesta del Nuevo Mundo), the National Polytechnical Symphony and the Bellas Artes Chamber Orchestra (Orquesta de Cámara de Bellas Artes).

The city is also a leading center of popular culture and music. There are a multitude of venues hosting Spanish and foreign-language performers. These include the 10,000-seat National Auditorium that regularly schedules the Spanish and English-language pop and rock artists, as well as many of the world's leading performing arts ensembles, the auditorium also broadcasts grand opera performances from New York's Metropolitan Opera on giant, high definition screens. In 2007 National Auditorium was selected world's best venue by multiple genre media.

Other sites for pop-artist performances include the 3,000-seat Teatro Metropolitan, the 15,000-seat Palacio de los Deportes, and the larger 50,000-seat Foro Sol Stadium, where popular international artists perform on a regular basis. The Cirque du Soleil has held several seasons at the Carpa Santa Fe, in the Santa Fe district in the western part of the city. There are numerous venues for smaller musical ensembles and solo performers. These include the Hard Rock Live, Bataclán, Foro Scotiabank, Lunario, Circo Volador and Voilá Acoustique. Recent additions include the 20,000-seat Arena Ciudad de México, the 3,000-seat Pepsi Center World Trade Center, and the 2,500-seat Auditorio Blackberry.

The Centro Nacional de las Artes (National Center for the Arts has several venues for music, theatre, dance. UNAM's main campus, also in the southern part of the city, is home to the Centro Cultural Universitario (the University Culture Center) (CCU). The CCU also houses the National Library, the interactive Universum, Museo de las Ciencias,[139] the Sala Nezahualcóyotl concert hall, several theatres and cinemas, and the new University Museum of Contemporary Art (MUAC).[140] A branch of the National University's CCU cultural center was inaugurated in 2007 in the facilities of the former Ministry of Foreign Affairs, known as Tlatelolco, in north-central Mexico City.

The José Vasconcelos Library, a national library, is located on the grounds of the former Buenavista railroad station in the northern part of the city.

The Papalote children's museum, which houses the world's largest dome screen, is located in the wooded park of Chapultepec, near the Museo Tecnológico, and La Feria amusement park. The theme park Six Flags México (the largest amusement park in Latin America) is located in the Ajusco neighborhood, in Tlalpan borough, southern Mexico City. During the winter, the main square of the Zócalo is transformed into a gigantic ice skating rink, which is said to be the largest in the world behind that of Moscow's Red Square.

The Cineteca Nacional (the Mexican Film Library), near the Coyoacán suburb, shows a variety of films, and stages many film festivals, including the annual International Showcase, and many smaller ones ranging from Scandinavian and Uruguayan cinema, to Jewish and LGBT-themed films. Cinépolis and Cinemex, the two biggest film business chains, also have several film festivals throughout the year, with both national and international movies. Mexico City has a number of IMAX theatres, providing residents and visitors access to films ranging from documentaries to blockbusters on these large screens.

Cuisine