Vivienne Westwood

Dame Vivienne Isabel Westwood DBE RDI (née Swire; born 8 April 1941) is a British fashion designer and businesswoman, largely responsible for bringing modern punk and new wave fashions into the mainstream.[1]

Vivienne Westwood DBE RDI | |

|---|---|

Westwood in 2008 | |

| Born | Vivienne Isabel Swire 8 April 1941 Tintwistle, Cheshire, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | University of Westminster |

| Occupation | Fashion designer, businesswoman |

Label(s) | Vivienne Westwood |

| Spouse(s) | Derek Westwood

( m. 1962; div. 1965) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | British Fashion Designer of the Year (1990, 1991, and 2006) |

Westwood came to public notice when she made clothes for Malcolm McLaren's boutique in the King's Road, which became known as SEX. Their ability to synthesise clothing and music shaped the 1970s UK punk scene which was dominated by McLaren's band, the Sex Pistols. She viewed punk as a way of "seeing if one could put a spoke in the system".[2]

Westwood opened four shops in London and eventually expanded throughout the United Kingdom and the world, selling an increasingly varied range of merchandise, some of which promoted her many political causes such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, climate change and civil rights groups.

Life and career

Early years

Westwood was born in the village of Tintwistle, Cheshire,[N 1] on 8 April 1941,[3] the daughter of Gordon Swire and Dora Swire (née Ball), who had married two years previously, two weeks after the outbreak of World War II.[4] At the time of Vivienne's birth, her father was employed as a storekeeper in an aircraft factory; he had previously worked as a greengrocer.[4]

In 1958, her family moved to Harrow, Middlesex, and Westwood took a jewellery and silversmith course at the University of Westminster, then known as the Harrow Art School,[5] but left after one term, saying: "I didn't know how a working-class girl like me could possibly make a living in the art world".[6] After taking up a job in a factory and studying at a teacher-training college, she became a primary school teacher. During this period, she created her own jewellery, which she sold at a stall on Portobello Road.[3]

In 1962, she met Derek Westwood, a Hoover factory apprentice, in Harrow.[7] They married on 21 July 1962; Westwood made her own wedding dress.[7] In 1963, she gave birth to a son, Benjamin (Ben) Westwood.[7]

Malcolm McLaren

Westwood's marriage to Derek ended after she met Malcolm McLaren. Westwood and McLaren moved into a council flat in Clapham, where their son Joseph Corré was born in 1967.[8] Westwood continued to teach until 1971 and also created clothes which McLaren designed. McLaren became manager of the punk band the Sex Pistols and subsequently the two garnered attention as the band wore Westwood's and McLaren's designs.

Punk era

Westwood was one of the architects of the punk fashion phenomenon of the 1970s, saying "I was messianic about punk, seeing if one could put a spoke in the system in some way".[7] The store that she co-managed with McLaren, SEX, was a meeting place for early members of the London punk scene. Westwood also inspired the style of punk icons, such as Viv Albertine, who wrote in her memoir, "Vivienne and Malcolm use clothes to shock, irritate and provoke a reaction but also to inspire change. Mohair jumpers, knitted on big needles, so loosely that you can see all the way through them, T-shirts slashed and written on by hand, seams and labels on the outside, showing the construction of the piece; these attitudes are reflected in the music we make. It's OK to not be perfect, to show the workings of your life and your mind in your songs and your clothes."[9]

Fashion collections

Westwood's designs were independent and represented a statement of her own values. She collaborated on occasions with Gary Ness, who assisted Westwood with inspirations and titles for her collections.[10]

McLaren and Westwood's first fashion collection to be shown to the media and potential international buyers was Pirate. Subsequently, their partnership, which was underlined by the fact that both their names appeared on all labelling, produced collections in Paris and London with the thematic titles Savages (shown late 1981), Buffalo/Nostalgia Of Mud (shown spring 1982), Punkature (shown late 1982), Witches (shown early 1983) and Worlds End 1984 (later renamed Hypnos, shown late 1983).[11] After the partnership with McLaren was dissolved, Westwood showed one more collection under the Worlds End label: "Clint Eastwood" (late 1984-early 1985).[12]

She dubbed the period 1981-85 "New Romantic" and 1988–91 as "The Pagan Years" during which "Vivienne's heroes changed from punks and ragamuffins to 'Tatler' girls wearing clothes that parodied the upper class". From 1985 to 1987, Westwood took inspiration from the ballet Petrushka to design the mini-crini, an abbreviated version of the Victorian crinoline.[13] Its mini-length, bouffant silhouette inspired the puffball skirts widely presented by more established designers such as Christian Lacroix.[14] The mini-crini was described in 1989 as a combination of two conflicting ideals - the crinoline, representing a "mythology of restriction and encumbrance in woman's dress", and the miniskirt, representing an "equally dubious mythology of liberation".[15]

In 2007, Westwood was approached by the Chair of King's College London, Patricia Rawlings, to design an academic gown for the college after it had successfully petitioned the Privy Council for the right to award degrees.[16] In 2008, the Westwood-designed academic dresses for King's College were unveiled. On the gowns, Westwood commented: "Through my reworking of the traditional robe I tried to link the past, the present and the future. We are what we know."[16]

In 2008, Heriot-Watt University awarded Westwood an honorary degree of Doctor of Letters for her contribution to the industry and use of Scottish textiles[17]

In July 2011, Westwood's collections were presented at The Brandery fashion show in Barcelona.[18]

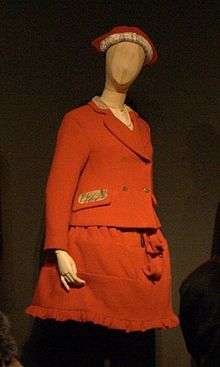

Westwood worked closely with Richard Branson to design uniforms for Virgin Atlantic crew. The uniform for the female crew consisted of a red suit, which accentuated the women's curves and hips, and had strategically placed darts around the bust area. The men's uniform consisted of a grey and burgundy three-piece suit with details on the lapels and pockets. Westwood and Branson were both passionate about using sustainable materials throughout their designs to reduce the impact on the environment and so used recycled polyester to make the uniforms. Before fully launching the designs, Westwood and Branson released some for a trial period with pilots and cabin crew and made changes using the feedback they received.[19]

Vivienne Westwood companies

In August 2011 Westwood's company Vivienne Westwood Ltd agreed to pay almost £350,000 in tax to HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) for significantly underestimating the value of her brand. Her UK business had sold the rights to her trademarks to Luxembourg-based Latimo, which she controlled, for £840,000 in 2002. After examining the deal, HMRC argued that Westwood's brand had been undervalued, and, after negotiation, the two sides agreed that her trademarks were worth more than double that amount. The £2m valuation triggered an additional tax bill of £348,463 plus interest of £144,112, which fell due in 2009.[20]

In March 2012, Vivienne Westwood Group reached agreement to end a long-standing UK franchise relationship with Manchester-based Hervia. The deal brought to a conclusion a legal wrangle which included Hervia issuing High Court proceedings for alleged breach of contract, after Westwood sought to end the franchise deal before the agreed term. It was reported that a financial settlement was reached between the parties. Hervia operated seven stores for the fashion chain on a franchise basis.[21]

In 2013, the transition of some of the Hervia stores to Westwood, along with cost-savings, was credited for a jump in Vivienne Westwood Ltd's pre-tax profits to £5 million from £527,683 the previous year, with annual group sales of £30.1 million up from £25.4 million.[22][23]

In 2014, the company results showed “disappointing” sales with a dip of 2% to £29.5 million and a fall of 36% in pre-tax profits to £3.2 million in 2013, according to accounts posted at Companies House. The company announced: "Over the last year margins have been under pressure due to the nature of wider retail conditions."[24]

In June 2013, Westwood announced she was shunning further expansion of her business as a way of tackling environmental and sustainability issues.[25]

In March 2015, the company announced that it was to open a three-storey outlet in midtown Manhattan in late 2015.[26] This was scheduled to be followed by a new 3,200 sq ft shop in a building also housing the company's offices and showrooms in Rue Saint-Honoré in Paris, due to open in early 2016.[27]

In 2015, Vivienne Westwood Ltd operated 12 retail outlets in the UK, including an outlet store in Bicester Village. There were 63 Westwood outlets worldwide including nine in China, nine in Hong Kong, eighteen in South Korea, six in Taiwan, two in Thailand, and two in the US.[28]

In June 2015, Vivienne Westwood Ltd reported a profit dip from £3.2m to £2.9m in 2014, despite an 8.4% jump in sales to £32m. VWL paid £1.6m in licence fees to Latimo and £646,033 in UK corporation tax in 2014, a 17% fall from the previous year.[29]

Several media outlets reported in 2015 that the accounts for Vivienne Westwood Ltd showed the company paid £2 million a year to offshore company Latimo, which was set up in Luxembourg for the right to use Westwood's name on her own fashion label.[30] Latimo, which Westwood controls as the majority shareholder in her companies, was set up in 2002.[20] Such arrangements, while legal, were against the Green Party policy to crack down heavily on usage of tax havens such as Luxembourg.[31] In March 2015 Westwood said "It is important to me that my business affairs are in line with my personal values. I am subject to UK tax on all of my income".[32] Later in 2015 she said that she had restructured her corporate tax arrangements to try to align them with the Green Party's policy.[33]

Notable clients and commissions

Marion Cotillard wore a Westwood red satin strapless dress at the London premiere of her film Public Enemies in 2009.[34] In 2013, she wore a Westwood Couture pink and ivory striped dress at the Chopard Lunch in Cannes.[35]

In 2011, Princess Eugenie wore three Westwood designs for the pre-wedding dinner, the wedding ceremony and the after-wedding party at the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton.[36]

Pharrell Williams wore a Westwood Buffalo hat to the 2014 56th Annual Grammy Awards that was originally in Westwood's 1982-83 collection. The hat was so popular that it inspired its own Twitter account. Pharrell was first seen wearing a similar Westwood Buffalo hat in 2009.[37]

Sex and the City

Westwood's designs were featured in the 2008 film adaptation of the television series Sex and the City. In the film, Carrie Bradshaw becomes engaged to long-term lover Mr. Big. Being a writer at Vogue, she is invited by her editor to model wedding dresses, including a design made by Westwood. The dress is subsequently sent to Carrie as a gift, with a handwritten note from Westwood herself, and Carrie decides to use the Westwood gown. The wedding dress has been described as one of the movie's most iconic features, leading Westwood to approach the producers about being involved in making a sequel.[38]

Political involvement

In April 1989 Westwood appeared on the cover of Tatler dressed as then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The suit that Westwood wore had been ordered for Thatcher but had not yet been delivered.[39][39] The cover, which bore the caption "This woman was once a punk", was included in The Guardian's list of the best ever UK magazine covers.[40]

Dame Vivienne stated on television in 2007 that she had transferred her long-standing support for the Labour Party to the Conservative Party, over the issues of civil liberties and human rights.[41] Since early 2015, she has been a supporter of the Green Party of England and Wales.[42]

On Easter Sunday 2008, she campaigned in person at the biggest Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament demonstration in ten years, at the Atomic Weapons Establishment, Aldermaston, Berkshire.[43]

In September 2005, Westwood joined forces with the British civil rights group Liberty and launched exclusive limited design T-shirts and baby wear bearing the slogan I AM NOT A TERRORIST, please don't arrest me. She said she was supporting the campaign and defending habeas corpus. "When I was a schoolgirl, my history teacher, Mr. Scott, began to take classes in civic affairs. The first thing he explained to us was the fundamental rule of law embodied in habeas corpus. He spoke with pride of civilisation and democracy. The hatred of arbitrary arrest by the lettres de cachet of the French monarchy caused the storming of the Bastille. We can only take democracy for granted if we insist on our liberty", she said.[44] The sale of the £50 T-shirts raised funds for the organisation.

In June 2013, Westwood dedicated one of her collections to Chelsea Manning and at her fashion show she and all of her models wore large image badges of Manning with the word "TRUTH" under her picture. In 2014, she cut off her hair to highlight the dangers of climate change.[45] She also appeared in a PETA ad campaign to promote World Water Day and vegetarianism, drawing attention to the meat industry's water consumption.[46]

In 2014, Westwood became ambassador for clean energy Trillion Fund.[47]

In June 2017, Westwood endorsed Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn for the 2017 UK general election. She said, "I'm excited about the Labour Party manifesto because it's all about the fair distribution of wealth." She added "Jeremy clearly wants to go green and creating a fair distribution of wealth is the place to start, from there we can build a green economy which will secure our future."[48][49] In November 2019, along with other public figures, Westwood signed a letter supporting Corbyn describing him as "a beacon of hope in the struggle against emergent far-right nationalism, xenophobia and racism in much of the democratic world" and endorsed for in the 2019 UK general election.[50]

Support of Green Party and exclusion from UK election campaign tour

In January 2015, Westwood announced her support of the Green Party of England and Wales: "I am investing in the Green Party because I believe it is in the best interests of our country and our economy'.[51]

It was reported that she had donated £300,000 to fund the party's election campaign.[52]

In February 2015, Westwood was announced as the special guest on the Greens' We Are The Revolution campaigning tour of English universities in such cities as Liverpool, Norwich, Brighton and Sheffield.[53]

On the eve of the tour, Westwood was excluded from appearing by the youth wing of the Green Party on the basis that her corporate avoidance of UK tax contravenes party policy on usage of off-shore havens.[54] She later condemned this as "a wasted opportunity" for the Greens. "I wasn't pure enough for them", she wrote in her online diary.[33]

Subsequently, Westwood switched her support to campaigning on behalf of Nigel Askew, the 'We are the Reality Party' candidate opposing UKIP leader Nigel Farage in the Kent constituency of Thanet South.[55] Askew polled 126 votes in the election.[56]

Active Resistance manifesto

In a 2007 interview Westwood spoke out against what she perceive as the "drug of consumerism",[57] and in 2009 she attended the première of The Age of Stupid, a film aimed at motivating the public to act against climate change.[58]

She later created a manifesto called Active Resistance to Propaganda,[59] which she says deals with the pursuit of art in relation to the human predicament and climate change.[60] In her manifesto, she makes the claim that it "penetrates to the root of the human predicament and offers the underlying solution. We have the choice to become more cultivated and therefore more human – or by muddling along as usual we shall remain the destructive and self-destroying animal, the victim of our own cleverness."[61]

Against the claim that anti-consumerism and fashion contradict each other, she said in 2007: "I don't feel comfortable defending my clothes. But if you've got the money to afford them, then buy something from me. Just don't buy too much."[60] She faces criticism from eco-activists who claim that despite her calls to save the environment she herself makes no concessions to making her clothing or her business eco-friendly.[62]

The manifesto was read by Westwood at a number of venues including the London Transport Museum before being staged at the Bloomsbury Ballroom by Forbidden London and Dave West (entrepreneur) on 4 December 2009. It starred Michelle Ryan and a number of other well known British actors.[63] [64]

The manifesto was written in the form of a play featuring many well known characters from pop culture including characters from Alice in Wonderland and distributed at readings as a booklet. Westwood was passionate about Gaia hypothesis at all her talks and frequently discussed the theories of futurologist James Lovelock as part of the events.

Julian Assange

Westwood is a longtime supporter of Julian Assange and has called for his release from custody. She visited him during his political asylum at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London and in Belmarsh Prison after his arrest in April 2019. She has used her appearances at London Fashion Week to push for his release. In July 2020, she protested outside London's Old Bailey court against Assange's possible extradition to the US by wearing a yellow pantsuit and suspending herself in a giant birdcage. Describing herself as the canary in the coal mine, she said she was "half-poisoned already from government corruption of law and gaming of the legal system by government".[65]

Questions over sustainability of Westwood clothing

In 2013, sustainable luxury fashion publication Eluxe Magazine accused Westwood of using the green movement as a marketing tool on the basis that certain Westwood fashion and accessories lines are made in China. These were found to include PVC, polyester, rayon and viscose, all derived from harmful chemicals.[66] Eluxe also pointed out that, in spite of Westwood's statements that consumers should 'buy less', her company produces nine collections a year (compared to the average designer's two) Vivienne Westwood was also accused of using unpaid interns in her fashions house and making them work over 40 hours per week, some interns have complained about how they had been treated by the fashion house.[67]

In 2014, as part of her Spring/Summer 15 collection, Westwood collaborated with the nonprofit organisation Farms Not Factories. Unveiled at Milan Fashion Week, the T-shirts and tote bags were produced using ethically sourced organic cotton.[68]

Westwood is also a noted author or co-author of books, such as Fashion in art: The Second Empire and Impressionism,[69][70] in which she explores the worlds of fashion and arts and links between the two worlds.

Recognition

In 1992, Westwood was awarded an OBE, which she collected from Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace. At the ceremony, Westwood was knicker-less, which was later captured by a photographer in the courtyard of Buckingham Palace. Westwood later said, "I wished to show off my outfit by twirling the skirt. It did not occur to me that, as the photographers were practically on their knees, the result would be more glamorous than I expected,"[71] and added: "I have heard that the picture amused the Queen."[71] Westwood advanced from OBE to DBE in the 2006 New Year's Honours List "for services to fashion", and has twice earned the award for British Designer of the Year.

In 2012, Westwood was among the British cultural icons selected by artist Sir Peter Blake to appear in a new version of his most famous artwork – the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover – to celebrate the British cultural figures of his life that he most admires.[72][73] Also in 2012, Westwood was chosen as one of The New Elizabethans to mark the diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II. A panel of seven academics, journalists and historians named Westwood among a group of 60 people in the UK "whose actions during the reign of Elizabeth II have had a significant impact on lives in these islands and given the age its character".[74]

In October 2014, the authorised biography Vivienne Westwood by Ian Kelly was published by Picador. Paul Gorman described it as "sloppy" and "riddled with inaccuracies" on the basis of multiple errors in the book including misspelling the names of popular rock stars “Jimmy” Hendrix and Pete “Townsend” and misidentifying the date of the Sex Pistols’ first concert and McLaren's age when he died in 2010.[75]

Picador publisher Paul Baggaley told The Bookseller: “We always take very seriously any errors that are brought to our attention and, where appropriate, correct them."[76] A spokesman for Pan MacMillan, which published an Australian edition of the biography, confirmed that the matter was being handled by the publisher's lawyers.[77]

In January 2011, Westwood was featured in a Canadian-made television documentary called Vivienne Westwood's London in which she takes the viewer through her favourite parts of London, including the Courtauld Institute of Art, the Wallace Collection, Whitechapel (accompanied by Sarah Stockbridge), Hampton Court, the London Symphony Orchestra, Brixton Market and Electric Avenue, and the National Gallery.[78]

In 2018 a documentary film about her, called Westwood: Punk, Icon, Activist, premiered.[79]

In 2019 Isabel Sanches Vegara wrote and Laura Callaghan illustrated Vivienne Westwood, one of the series, Little People, BIG DREAMS, published by Frances Lincoln Publishing.[80]

Personal life

Westwood is married to her former fashion student, Austrian Andreas Kronthaler. For 30 years she lived in an ex-council flat in Nightingale Lane, Clapham,[81] until, in 2000, Kronthaler convinced her to move into a Queen Anne style house built in 1703, which once belonged to the mother of Captain Cook.[82] She is a keen gardener.[83] Westwood is vegetarian as well.[46]

Children

- Ben Westwood (born 1963), son of Vivienne and Derek Westwood, is a photographer of erotica.

- Joseph Corré (born 1967), son of Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren, is the founder of lingerie brand Agent Provocateur.[84]

Notes

- In 1941, Tintwistle was in the county of Cheshire when Vivienne was born but since 1974, it has been part of Derbyshire.

References

- Bell-Price, Shannon. "Vivienne Westwood (born 1941) and the Postmodern Legacy of Punk Style Source: Vivienne Westwood (born 1941) and the Postmodern Legacy of Punk Style". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Adams, William Lee (2 April 2012). "Vivienne Westwood - All-TIME 100 Fashion Icons - TIME". Time. TIME. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Susannah Frankel (20 October 1999). "Meet the grande dame of Glossop". The Independent. London, UK. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- Nick Barratt (24 February 2007). "Family detective". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- "Vivienne Westwood chooses University of Westminster for London Fashion Week catwalk show". University of Westminster. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Vivienne Westwood – The Early Years". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- "Vivienne Westwood: Disgracefully yours, the Queen Mother of Fashion". The Independent. London, UK. 2 June 2002. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- "Joe Corré and Serena Rees: Sex and the City". The Independent. 29 July 2002. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010.

- Albertine, Viv, 1954-. Clothes, clothes, clothes : music, music, music : boys, boys, boys : a memoir (First U.S. ed.). New York, N.Y. pp. 130–131. ISBN 9781250065995. OCLC 886381785.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- O'Neill, Alistair (21 April 2015). "Exhibition Review: Vivienne Westwood: 34 Years in Fashion". Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture: 381–386.

- "Vivienne Westwood: the early years". Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Vermorel, Fred (1996). Vivienne Westwood : fashion, perversity and the sixties laid bare. Woodstock, N.Y.: Overlook. p. 94. ISBN 9780879516918.

- Staff. "Vivienne Westwood designs". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Evans, Caroline (2004). "Cultural Capital 1976-2000". In Breward, Christopher; Ehrman, Edwina; Evans, Caroline (eds.). The London look: fashion from street to catwalk. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press/Museum of London. p. 149. ISBN 9780300103991.

- Evans, Caroline; Thornton, Minna (1989). Women and Fashion: A New Look. London, UK: Quartet Books. pp. 148–50. ISBN 9780704326910.

- "Comment: The College Newsletter: Westwood unveils gowns" (PDF). Kcl.ac.uk. September 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "Westwood praises fashion campus". BBC. 22 April 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- The Brandery, Catwalk, TV Fashion Runway Show Archived 3 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, thebrandery.com; accessed 20 February 2016.

- Karimzadeh, Marc (2 May 2013). "Vivienne Westwood Takes Flight With Richard Branson On Virgin Atlantic". Trade Journals. 205 (90). ProQuest 1349800397.

- Tyler, Richard. "Vivienne Westwood undervalues itself". Telegraph. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "Vivienne Westwood Group and Hervia agree to settlement". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "Cost cuts at Vivienne Westwood fashions a profit rise". This is Money. 21 September 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/company/02682271/filing-history

- Russell Lynch (8 August 2014). "Vivienne Westwood profits fall after 'disappointing' year". Standard.co.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Binnie, Isla (24 June 2013). "Designer Vivienne Westwood shuns expansion, big wardrobes". Reuters. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Khanh T.L. Tran (23 March 2015). "Vivienne Westwood Opening First Boutique in New York". Wwd.com. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "Vivienne Westwood coming to Rue Saint-Honoré in Paris". Uk.fashionmag.com. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "Store Locator". VivienneWestwood.com. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Armstrong, Ashley (27 June 2015). "Vivienne Westwood sales rise while profits wilt". Telegraph. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "Vivienne Westwood accused of hypocrisy over offshore tax base". Telegraph. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Nicola Woolcock (9 March 2015). "Vivienne Westwood accused of £2m tax avoidance". The Times. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "Vivienne Westwood Responds To Tax Avoidance Claims". Vogue.co.uk. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "Climate Revolution". Climate Revolution. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "Marion Cotillard Wears Red Vivienne Westwood Dress at Public Enemies Premiere in London". PopSugar. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- "Marion Cotillard In Vivienne Westwood - Chopard Lunch". redcarpet-fashionawards.com. 17 May 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- "Week in Review: Princess Eugenie, 24–30 April". The Royal Order of Sartorial Splendor. 5 May 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- "Fashion Articles - Grazia". Graziadaily.co.uk. gb. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Barnett, Leisa (7 January 2009). "Sex And The Dame)". Vogue.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Biography: Dame Vivienne Westwood". BBC. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "Are these the best ever UK magazine covers?". The Guardian. London, UK. 8 August 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "New Conservative Vivienne Westwood has something to get off her chest". Vogue.co.uk. 29 November 2007. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Vivienne Westwood: 'We'll all be migrants soon'". The Guardian. 20 September 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- "Vivienne Westwood rallies at CND's Easter Monday demonstration in Berkshire". Vogue.co.uk. 25 March 2008. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Browning, Anna (28 September 2005). "The power of T-shirt slogans". BBC News. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Olivia Bergin, Vivienne Westwood Cut Off Her Hair To Promote Climate Change, Telgraph.co.uk, 6 March 2014.

- Sowray, Bibby (18 March 2014). "Vivienne Westwood Takes a Shower To Promote World Water Day". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- "Vivienne Westwood becomes ambassador for clean energy Trillion Fund". Climate Action Programme. 17 February 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Sisley, Dominique (2 June 2017). "Vivienne Westwood comes out in support of Jeremy Corbyn". Dazed. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Doig, Stephen (12 June 2017). "Bill Bailey on happiness, Jeremy Corbyn and how turning 50 changed him". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Neale, Matthew (16 November 2019). "Exclusive: New letter supporting Jeremy Corbyn signed by Roger Waters, Robert Del Naja and more". NME. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- "Vivienne Westwood: Vote Green 2015!". News. Green Party of England and Wales. 23 January 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Cowburn, Ashley (23 January 2015). "Fashion designer Vivienne Westwood to donate £300,000 to the Green party". New Statesman. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Sherriff, Lucy (20 February 2015). "Vivienne Westwood To Tour Universities To Promote Green Party To Students". Huffington Post UK. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- "Vivienne Westwood defrocked by Greens over 'tax avoidance'". Telegraph. 21 March 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "Vivienne's Diary". Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- "Thanet South parliamentary constituency - Election 2015". BBC News. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Brockes, Emma (11 May 2007). "All hail the Queen". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- "Age of Stupid premiere: the green carpet treatment". The Guardian. London, UK. 16 March 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- "Climate Revolution : Vivienne's Diary". Activeresistance.co.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Cadwallader, Carole (2 December 2007). "I don't feel comfortable defending my clothes. But if you've got the money to afford them, then buy something from me. Just don't buy too much". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- Vivienne Westwood, Manifesto, activeresistance.co.uk; accessed 20 February 2016.

- "Vivienne Westwood's Climate Revolution Charter: A Critique". Eluxe Magazine. 28 March 2013. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Vivienne Westwood's - 'Active Resistance to Propaganda'- Forbidden London- part 1

- Vivienne Westwood's Active Resistance To Propaganda

- Holland, Oscar. "Vivienne Westwood suspends herself in giant birdcage to protest Assange's extradition". CNN. CNN. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- James Lyons (15 March 2015). "Westwood's anti-fracking frock turns toxic". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "Why Vivienne Westwood is Not Eco Friendly". Eluxe Magazine. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Christian Madsen, Anders (23 June 2014). "vivienne westwood spring/summer 15 menswear". I-d.

- "Fashion in art : the Second Empire and impressionism - OpenBibArt". www.openbibart.fr. 1995. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- "Fashion in Art". www.goodreads.com. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- "Vivienne Westwood: You ask the questions". The Independent. London. 21 February 2001. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- "New faces on Sgt Pepper album cover for artist Peter Blake's 80th birthday". The Guardian. 5 October 2016.

- "Sir Peter Blake's new Beatles' Sgt Pepper's album cover". BBC. 9 November 2016.

- "The New Elizabethans - Vivienne Westwood". BBC. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- Adam Sherwin (16 October 2014). "Vivienne Westwood accused of plagiarism over book on her life". The Independent. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Coben, Harlan (17 October 2014). "Gorman claims Westwood biography plagiarism". The Bookseller. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Jason Steger (9 November 2014). "Legal action looms over Vivienne Westwood biography". Smh.com.au. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Heather Toskan, QMI Agency, Vivienne Westwood's London; accessed 6 April 2016.

- Weaver, Hilary (8 March 2018). "The Vivienne Westwood Documentary Vivienne Westwood Doesn't Want You to See". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- Sanchez Vegara, Isabel (2019). Vivienne Westwood. Callaghan, Laura (illustrator). London: Frances Lincoln Publishing. ISBN 9781786037565. OCLC 1084387173.

- Sharkey, Alix (8 April 2001). "Westwood ho!". The Observer. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Cathy Horyn (31 December 2009). "The Queen V". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- Piers Beeching (6 August 2009). "Me & my garden: Vivienne Westwood". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- "Vivienne Westwood's son Ben Breaks into Men's Fashion". zimbio.com. Archived from the original on 22 July 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Vivienne Westwood |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vivienne Westwood. |