Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; Irish: Óglaigh na hÉireann[12]), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA or Provos), was an Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland,[13] facilitate Irish reunification and bring about an independent republic encompassing all of Ireland.[14][15] It was the most active republican paramilitary group during the Troubles. It saw itself as the military force of an all-island Irish Republic, and as the sole legitimate successor to the original IRA from the Irish War of Independence. It was designated a terrorist organisation in the United Kingdom and an illegal organisation in the Republic of Ireland, both of whose authority it rejected.[16][17]

| Provisional Irish Republican Army | |

|---|---|

Óglaigh na hÉireann Participant in the Troubles | |

IRA members showing an improvised mortar and an RPG-7 (1992) | |

| Active | 1969–2005 (on ceasefire from 1997) |

| Ideology | Physical force Irish Republicanism Socialism Left-wing nationalism Irish nationalism[1] |

| Allegiance | |

| Leaders | Army Council |

| Area of operations | Ireland England Continental Europe |

| Size | In total, the lowest estimate was 8,000, the highest 30,000. Martin McGuinness, the former Derry commander, also said he believed that 10,000 passed through its ranks.[3] At any one time Ed Moloney wrote the Belfast Brigade alone had 1,200 volunteers active at its peak in 1972. By the 1980s with the cell structure re-organisation the Belfast IRA had been lowered to 100 active, with about 300–400 volunteers active in total, with about another 450 in support roles.[4][5] |

| Allies | ETA[7] FARC[7] |

| Opponent(s) | Ulster loyalist paramilitaries[11] |

The Provisional IRA emerged in December 1969, following a split within the previous incarnation of the IRA and the broader Irish republican movement. It was the minority faction in the split, while the majority continued as the Official IRA. The Troubles had begun shortly before when a largely Catholic, nonviolent civil rights campaign was met with violence from both Ulster loyalists and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), culminating in the August 1969 riots and deployment of British troops.[18] The IRA initially focused on defence of Catholic areas, but it began an offensive campaign in 1971 (see timeline). The IRA's primary goal was to force a British withdrawal from Northern Ireland.[19] It used guerrilla tactics against the British Army and RUC in both rural and urban areas. It also carried out a bombing campaign in Northern Ireland and England against what it saw as political and economic targets.

The Provisional IRA declared a final ceasefire in July 1997, after its political wing Sinn Féin was re-admitted into the Northern Ireland peace talks. It supported the 1998 Good Friday Agreement and in 2005 it disarmed under international supervision. Several splinter groups have been formed as a result of splits within the IRA, including the Continuity IRA (which formed in 1986 but did not become active until after the Provisional IRA ceasefire of 1994) and the Real IRA (after the final 1997 ceasefire), both of which are still active in the low-level dissident Irish republican campaign. The IRA's armed campaign, primarily in Northern Ireland but also in England and mainland Europe, caused the deaths of over 1,700 people. The dead included around 1,000 members of the British security forces, and 500–644 civilians.[20][21] The IRA itself lost 275–300 members,[22][23] and an estimated 10,000 imprisoned at various times over the 30-year period.[3][24]

Organisation

Leadership

All levels of the organisation were entitled to send delegates to General Army Conventions.[25] The convention was the IRA's supreme decision-making authority, and was supposed to meet every two years,[25] or every four years following a change to the IRA's constitution in 1986.[1][n 2] Before 1969 conventions met regularly, but owing to the difficulty in organising such a large gathering of an illegal organisation in secret,[27] while the IRA's armed campaign was ongoing they were only held in September 1970,[27] October 1986,[27] and October or November 1996.[28][29] Since the 1997 ceasefire they were held more frequently, and are known to have been held in October 1997,[30] May 1998,[31] December 1998 or early 1999,[32][33] and June 2002.[34]

The convention elected a 12-member Executive,[n 3] which selected seven members, usually from within the Executive, to form the Army Council.[36][25] Any vacancies on the Executive would then be filled by substitutes previously elected by the convention.[25] For day-to-day purposes, authority was vested in the Army Council which, as well as directing policy and taking major tactical decisions, appointed a Chief of Staff from one of its number or, less often, from outside its ranks.[37][38]

The Chief of Staff would appoint an adjutant general as well as a General Headquarters (GHQ) staff, which consisted of directors of the following departments:

- Quartermaster

- Finance

- Engineering

- Training

- Intelligence

- Publicity

- Operations

- Security[36]

Regional command

Below GHQ, the IRA was divided into a Northern Command and a Southern Command.[36] Northern Command operated in the nine Ulster counties as well as the border counties of Leitrim and Louth, and Southern Command operated in the remainder of Ireland.[39] The Provisional IRA was originally commanded by a leadership based in Dublin. However, in 1977, parallel to the introduction of cell structures at the local level, command of the "war-zone" was given to the Northern Command. These moves at re-organisation were the idea of Ivor Bell, Gerry Adams and Brian Keenan.[40] Southern Command consisted of the Dublin Brigade and a number of smaller units in rural areas.[36] Its main responsibilities were support activities for Northern Command, such as importation and storage of arms, providing safe houses, raising funds through robberies, and organising training camps.[41][42]

Brigades

The IRA referred to its ordinary members as volunteers (or óglaigh in Irish), to reflect the IRA being an irregular army which people were not forced to join and could leave at any time.[43] Until the late 1970s, IRA volunteers were organised in units based on conventional military structures. Volunteers living in one area formed a company as part of a battalion, which could be part of a brigade such as the Derry Brigade,[36] South Armagh Brigade,[44] and East Tyrone Brigade.[45] The Belfast Brigade had three battalions, in the west, north and east of the city. In the early years of the Troubles, the IRA in Belfast expanded rapidly; in August 1969, the Belfast Brigade had just 50 active members – by the end of 1971, it had 1,200 members, giving it a large but loosely controlled structure.[46]

Active service units

In late 1973 the IRA in Belfast restructured, introducing clandestine cells named active service units (ASU), consisting of between four and ten members.[47] Similar changes were made elsewhere in the IRA by 1977, moving away from the larger conventional military organisational principle owing to its security vulnerability.[48][49] A system of two parallel types of unit within an IRA brigade was introduced in place of the battalion structures. Firstly, the old "company" structures were used for support activities such as "policing" nationalist areas, intelligence-gathering, and hiding weapons.[50] The bulk of actual attacks were carried out by the second type of unit, the ASU, using weapons controlled by the brigade's quartermaster.[36] It was estimated that in the late 1980s the IRA had roughly 300 members in ASUs and about another 450 serving in supporting roles.[51] The exception to this reorganisation was the South Armagh Brigade, which retained its traditional hierarchy and battalion structure and used relatively large numbers of volunteers in its actions.[52] South Armagh did not have the same problems with security that other brigades had, with less arrests than any other area and only a handful of IRA volunteers were convicted of serious offences.[53]

History

Origins

The IRA was formed in 1913 as the Irish Volunteers, at a time when all Ireland was part of the United Kingdom.[54] The Volunteers took part in the Easter Rising against British rule, and the War of Independence, during which they came to be known as the Irish Republican Army.[54] The subsequent Anglo-Irish Treaty, which partitioned Ireland into the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland, which remained part of the United Kingdom, caused a split in the IRA, the pro-Treaty IRA being absorbed into the National Army, which defeated the anti-Treaty IRA in the Civil War.[55][56] Subsequently, while denying the legitimacy of the Free State, the IRA focused on overthrowing the Northern Ireland state and the achievement of a united Ireland, carrying out a bombing campaign in England in 1939 and 1940,[57] a campaign in Northern Ireland in the 1940s,[58] and the Border campaign of 1956–1962.[59] Following the failure of the Border campaign, internal debate took place regarding the future of the IRA.[60] Chief-of-staff Cathal Goulding wanted the IRA to adopt a socialist agenda and become involved in politics, while traditional republicans such as Seán Mac Stíofáin wanted to increase recruitment and rebuild the IRA.[61][62]

Following partition Northern Ireland became a de facto one-party state governed by the Ulster Unionist Party, in which Catholics viewed themselves as second-class citizens.[63][64] Protestants were given preference in jobs and housing, and local government constituencies were gerrymandered in places such as Derry.[65] Policing was carried out by the armed Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the B-Specials, both of which were almost exclusively Protestant.[66] In the mid-1960s tension between the Catholic and Protestant communities was increasing.[65] In 1966 Ireland celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising, prompting fears of a renewed IRA campaign.[67] Feeling under threat, Protestants formed the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), which killed three people in May 1966, two of them Catholic men.[65] In January 1967 the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was formed by a diverse group of people, including IRA members and liberal unionists.[68] Civil rights marches by NICRA and a similar organisation, People's Democracy, protesting against discrimination were met by counter-protests by loyalists, including the Ulster Protestant Volunteers led by Ian Paisley, resulting in violent clashes.[69][70]

Protestant marches celebrating The Twelfth in July 1969 led to riots and violent clashes in Belfast, Derry and elsewhere.[71][72] The following month a three day riot began in the Bogside area of Derry, following a march by the Protestant Apprentice Boys of Derry.[73] The Battle of the Bogside caused Catholics in Belfast to riot in solidarity with the Bogsiders and to try and prevent RUC reinforcements being sent to Derry, sparking retaliation by Protestant mobs.[74] The subsequent burning, damage to property and intimidation, forced 1,800 people (1,505 of them Catholics[75]) from their homes in Belfast in the Northern Ireland riots of August 1969, with over 200 Catholic homes being destroyed or requiring major repairs.[18] A number of people were killed on both sides, some by the police, and the British Army were deployed to Northern Ireland. The IRA had been poorly armed and its defence of Catholic-majority areas from Protestants, which had been considered one of its traditional roles since the 1920s, was seen by many as inadequate.[76] Veteran republicans were critical of Cathal Goulding and the IRA's Dublin leadership which, for political reasons, had refused to prepare for aggressive action in advance of the violence.[77][78] On 24 August a group including Joe Cahill, Seamus Twomey, Dáithí Ó Conaill, Billy McKee, and Jimmy Steele came together in Belfast and decided to remove the pro-Goulding Belfast leadership of Billy McMillen and Jim Sullivan and turn back to traditional militant republicanism.[79] On 22 September Twomey, McKee and Steel were among sixteen armed IRA men who confronted the Belfast leadership over the failure to adequately defend Catholic areas.[79] A compromise was agreed where McMillen stayed in command, but he was not to have any communication with the IRA's Dublin based leadership.[79]

1969 split

Traditional republicans formed the "Provisional" Army Council in December 1969, after an IRA convention was held at Knockvicar House in Boyle, County Roscommon.[80][81] The two main issues were a motion to enter into a "National Liberation Front" with radical left-wing groups, and a motion to end abstentionism, which would allow participation in the British, Irish and Northern Ireland parliaments.[80] The traditionalists refused to vote on the "National Liberation Front" and it was passed by twenty-nine votes to seven.[80][82] The traditionalists argued strongly against the ending of abstentionism, and the official minutes report the motion passed by twenty-seven votes to twelve.[n 4][80][82] IRA Director of Intelligence Seán Mac Stíofáin announced that he no longer considered that the IRA leadership represented republican goals, however there was no walkout.[80][83] Those opposed, who included Mac Stíofáin and Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, refused to go forward for election to the new Executive.[80]

While others canvassed support throughout Ireland, Mac Stíofáin was a key person making a connection with the Belfast IRA under Billy McKee and Joe Cahill, who had refused to take orders from the IRA's Dublin leadership since September 1969, in protest at their failure to defend Catholic areas in August.[85][86] Nine out of thirteen IRA units in Belfast sided with the Provisionals in December 1969, roughly 120 activists and 500 supporters.[87] The first "Provisional" Army Council was composed of Seán Mac Stíofáin, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, Paddy Mulcahy, Sean Tracey, Leo Martin, Dáithí Ó Conaill and Joe Cahill.[88] The term "provisional" was chosen to mirror the 1916 Provisional Government of the Irish Republic,[80] and also to designate it as temporary pending reorganisation of the movement.[88] Although this reorganisation eventually happened in 1970, the name stuck.[88] The Provisional IRA issued their first public statement on 28 December 1969, stating:

We declare our allegiance to the 32 county Irish republic, proclaimed at Easter 1916, established by the first Dáil Éireann in 1919, overthrown by force of arms in 1922 and suppressed to this day by the existing British-imposed six-county and twenty-six-county partition states.[n 5][2]

The Sinn Féin party split along the same lines on 11 January 1970, when a third of the delegates walked out of the Ard Fheis in protest at the party leadership's attempt to force through the ending of abstentionism, despite its failure to achieve a two-thirds majority vote of delegates required to change the policy.[91] Despite the declared support of that faction of Sinn Féin, the early Provisional IRA was extremely suspicious of political activity, arguing rather for the primacy of armed struggle.[92]

What would become the Provisional IRA received arms and funding from the Fianna Fáil-led Irish government in 1969, resulting in the 1970 Arms Crisis in which criminal charges were pursued against two former government ministers and others including Belfast IRA volunteer John Kelly. Roughly £100,000 was donated by the Irish government to "Defence Committees" in Catholic areas and, according to historian Richard English, "there is now no doubt that some money did go from the Dublin government to the proto-Provisionals".[93]

The Provisionals maintained the principles of the pre-1969 IRA; they considered both British rule in Northern Ireland and the government of the Republic of Ireland to be illegitimate, insisting that the Army Council was the only valid government, as head of an all-island Irish Republic. This belief was based on a series of perceived political inheritances which constructed a legal continuity from the Second Dáil.[94][15]

By 1971, the Provisionals had inherited most of the existing IRA organisation in Northern Ireland, as well as the more militant IRA members in the rest of Ireland. In addition, they recruited many young nationalists from Northern Ireland, who had not been involved in the IRA before but had been radicalised by the violence that broke out in 1969. These people were known in republican parlance as "sixty niners", having joined after 1969.[95] The Provisional IRA adopted the phoenix as the symbol of the Irish republican rebirth in 1969. One of its slogans was "out of the ashes rose the Provisionals".[96]

Initial phase

Following the violence of August 1969, the IRA began to arm and train to protect nationalist areas from further attack.[97] In January 1970 the Army Council decided to adopt a three-stage strategy; defence of nationalist areas, followed by a combination of defence and retaliation, and finally launching a guerrilla campaign against the British Army.[98]

The Official IRA was opposed to such a campaign because they felt it would lead to sectarian conflict, which would defeat their strategy of uniting the workers from both sides of the sectarian divide. The IRA's 1956–62 Border Campaign had avoided actions in urban centres of Northern Ireland to avoid civilian casualties and probable resulting sectarian violence.[99]

The Provisional IRA's strategy was to use force to cause the collapse of the government of Northern Ireland and to inflict such casualties on the British forces that the British government would be forced by public opinion to withdraw from Ireland. According to journalist Brendan O'Brien, "the thinking was that the war would be short and successful. Chief of Staff Seán Mac Stíofáin decided they would 'escalate, escalate and escalate' until the British agreed to go".[100] This policy involved recruitment of volunteers and carrying out attacks on British forces, as well as mounting a bombing campaign against economic targets.[101][102] The economic bombing campaign began in 1971, with the IRA being responsible for the vast majority of the 1,000 explosions that occurred in Northern Ireland that year.[103] In the early years of the conflict, IRA slogans spoke of, "Victory 1972" and then "Victory 1974".[101] Its inspiration was the success of the "Old IRA" in the Irish War of Independence (1919–1922), which also relied on British public opinion to achieve its aims. In their assessment of the IRA campaign, the British Army would describe the period from the mid-1971 to the mid-1970s as a "classic insurgency".[104]

In June 1972 the IRA brought out the Éire Nua (New Ireland) policy, which advocated an all-Ireland federal republic, with decentralised governments and parliaments for each of the four historic provinces of Ireland.[105] The British government held secret talks with the IRA leadership in 1972 to try to secure a ceasefire based on a compromise settlement after the events of Bloody Sunday led to an increase in IRA recruitment and support. The IRA agreed to a temporary ceasefire from 26 June to 9 July. In July 1972, Seán Mac Stíofáin, Dáithí Ó Conaill, Ivor Bell, Seamus Twomey, Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness met a British delegation led by William Whitelaw. The republicans refused to consider a peace settlement that did not include a commitment to British withdrawal, a retreat of the British Army to its barracks, and a release of republican prisoners. The British refused and the talks broke up.[106]

1975 ceasefire

By the mid-1970s, the hopes of the IRA leadership for a quick military victory were receding and the British military was unsure of when it would see any substantial success against the IRA. Secret meetings between Provisional IRA leaders Ruairí Ó Brádaigh and Billy McKee with British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Merlyn Rees secured an IRA ceasefire which began in February 1975. The IRA initially believed that this was the start of a long-term process of British withdrawal, but later came to the conclusion that the British were unwilling and/or unable to make concessions in areas they deemed crucial.[107][108] Critics of the IRA leadership, most notably Gerry Adams, felt that the ceasefire was disastrous for the IRA, leading to infiltration by British informers, the arrest of many activists and a breakdown in IRA discipline resulting in sectarian killings and a feud with fellow republicans in the Official IRA. At this time, the IRA leadership, short of money, weapons, and members was on the brink of calling off the campaign. However, the ceasefire was ended in January 1976 instead.[109]

The "Long War"

Thereafter, the IRA evolved a new strategy which they called the "Long War". This underpinned IRA strategy for the rest of the Troubles and involved the re-organisation of the IRA into small cells, an acceptance that their campaign would last many years before being successful and an increased emphasis on political activity through Sinn Féin. A republican document of the early 1980s states: "Both Sinn Féin and the IRA play different but converging roles in the war of national liberation. The Irish Republican Army wages an armed campaign... Sinn Féin maintains the propaganda war and is the public and political voice of the movement".[110] The 1977 edition of the Green Book, an induction and training manual used by the IRA, describes the strategy of the "Long War" in these terms:

- A war of attrition against enemy personnel [British Army] based on causing as many deaths as possible so as to create a demand from their [the British] people at home for their withdrawal.

- A bombing campaign aimed at making the enemy's financial interests in our country unprofitable while at the same time curbing long-term investment in our country.

- To make the Six Counties... ungovernable except by colonial military rule.

- To sustain the war and gain support for its ends by National and International propaganda and publicity campaigns.

- By defending the war of liberation by punishing criminals, collaborators and informers.[19]

The Éire Nua policy was discontinued by the Army Council in 1979[111] but remained Sinn Féin policy until 1982,[112] reflecting the sequence in which the old leadership of the republican movement were being sidelined.

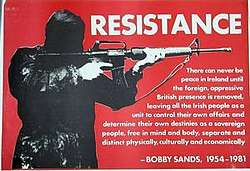

IRA prisoners convicted after March 1976 did not have Special Category Status applied in prison. In response, more than 500 prisoners refused to wear prison clothes. This activity culminated in the 1981 Irish hunger strike, when seven IRA and three Irish National Liberation Army members starved themselves to death in pursuit of political status. The hunger strike leader Bobby Sands and Anti H-Block activist Owen Carron were elected to the British Parliament, and two other protesting prisoners were elected to the Dáil. In addition, there were work stoppages and large demonstrations all over Ireland in sympathy with the hunger strikers. More than 100,000 people attended the funeral of Sands, the first hunger striker to die.[113]

Peace process

The success of the 1981 Irish hunger strike in mobilising support and winning elections led to the "Armalite and ballot box strategy", named after Danny Morrison's speech at the 1981 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis (annual meeting):

Who here really believes that we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if with a ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in this hand we take power in Ireland?[114]

The IRA made an attempt to escalate the conflict with the so-called "Tet Offensive" in the 1980s, which was reluctantly approved by the Army Council and did not prove successful. The perceived stalemate along with British government's hints of a compromise[115] and secret approaches in the early 1990s led republican leaders increasingly to look for a political agreement to end the conflict,[116][117] with a broadening dissociation of Sinn Féin from the IRA. Public speeches from two Northern Ireland Secretaries of State, Peter Brooke[118] and Patrick Mayhew[119] hinted that, given the cessation of violence, a political compromise with the IRA was possible. Gerry Adams entered talks with John Hume, the leader of the moderate nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) in 1993, and secret talks were also conducted since 1991 between Martin McGuinness and a senior MI6 officer, Michael Oatley.[115][117][120] Thereafter, Adams increasingly tried to disassociate Sinn Féin from the IRA, stating they were separate organisations and refusing to speak on behalf of the IRA.[121]

The new strategy was described by the acronym "TUAS", described as either "Tactical Use of Armed Struggle" to the Irish republican movement or "Totally Unarmed Strategy" to the broader Irish nationalist movement.[122] Following the negotiations with the SDLP and secret talks with British civil servants, the IRA ultimately called a ceasefire in 1994 on the understanding that Sinn Féin would be included in political talks for a settlement.[123] When the British government then demanded the disarmament of the IRA before it allowed Sinn Féin into multiparty talks, the organisation called off its ceasefire in February 1996. The renewed bombings caused severe economic damage, with the Manchester bombing and the Docklands bombing causing approximately £800 million in combined damage.

After the IRA declared a new ceasefire in July 1997, Sinn Féin was admitted into all-party talks, which produced the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. One aim of the agreement was that all paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland cease their activities and disarm by May 2000. Calls from Sinn Féin led the IRA to commence disarming in a process that was monitored by Canadian General John de Chastelain's decommissioning body in October 2001,[124] and some weapons were decommissioned on 23 October 2001 and 11 April 2002.[125] In October 2002 the devolved Northern Ireland Assembly was suspended by the British government and direct rule returned, in order to prevent a unionist walkout.[126] This was partly triggered by Stormontgate—allegations that republican spies were operating within Parliament Buildings and the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI)[127]—and the IRA temporarily broke off contact with General de Chastelain.[128] However, further decommissioning took place on 21 October 2003.[125] In the aftermath of the December 2004 Northern Bank robbery, Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform Michael McDowell stated there could be no place in government in either Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland for a party that supported or threatened the use of violence, possessed explosives or firearms, and was involved in criminality.[129] At the beginning of February 2005, the IRA declared that it was withdrawing a decommissioning offer from late 2004.[129] This followed a demand from the Democratic Unionist Party, under Ian Paisley, insisting on photographic evidence of decommissioning.[129]

End of the armed campaign

On 28 July 2005, the Army Council announced an end to the armed campaign, stating that it would work to achieve its aims solely by peaceful political means. The Army Council stated that it had ordered volunteers to dump all weapons and to end all paramilitary activity. It also announced that the IRA would complete the process of disarmament as quickly as possible.[130]

This was not the first time that an organisation calling itself the IRA had issued orders to dump arms.[131] After its defeat in the Irish Civil War in 1924 and at the end of its unsuccessful Border Campaign in 1962, the IRA issued similar orders.[131] However, this was the first time that an Irish republican paramilitary organisation had voluntarily decided to dispose of its arms.[131] On 26 September 2005, the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning (IICD) announced that "the totality of the IRA's arsenal" had been decommissioned. The IRA invited two independent witnesses to view the secret disarmament work: Catholic priest Father Alec Reid and Protestant minister Reverend Harold Good.[132][133] Among the weaponry, estimated by Jane's Information Group, to have been decommissioned as part of this process were:

- 1,000 rifles

- 2 tonnes of Semtex

- 20–30 heavy machine guns

- 7 surface-to-air missiles (unused)

- 7 flamethrowers

- 1,200 detonators

- 11 rocket-propelled grenade launchers

- 90 handguns

- 100+ hand grenades[134]

Having compared the weapons decommissioned with the British and Irish security forces' estimates of the IRA's arsenal, and because of the IRA's full involvement in the process of decommissioning the weapons, the IICD arrived at their conclusion that all IRA weaponry has been decommissioned.[n 6][136] The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Peter Hain, said he accepted the conclusion of the IICD.[137] Since then, there have been occasional claims in the media that the IRA had not decommissioned all of its weaponry. In response to such claims, the Independent Monitoring Commission (IMC) stated in its tenth report that the IRA had decommissioned all weaponry "under its control".[138] It said that if any weapons had been kept, they would have been kept by individuals and against IRA orders.[n 7][138]

Some former members of the IRA have joined dissident republican paramilitary organisations, including the Continuity IRA,[141] the Real IRA,[142] Republican Action Against Drugs,[143] and the New IRA.[144]

In February 2015, the Garda Commissioner stated that Gardaí have no evidence that the IRA's military structure remains or that the IRA is engaged in crime.[145] In August 2015, the PSNI Chief Constable stated that the IRA no longer exists as a paramilitary organisation. He said that some of its structure remains, but that the group is committed to following a peaceful political path and is not engaged in criminal activity or directing violence.[146] However, he added that some members have engaged in criminal activity or violence for their own ends.[146] The statement was in response to the recent killings of two former IRA members. In May, former IRA commander Gerard Davison was shot dead in Belfast. He had been involved in Direct Action Against Drugs and it is believed he was killed by an organised crime gang. Three months later, former IRA member Kevin McGuigan was also shot dead in Belfast. It is believed he was killed by the group Action Against Drugs, in revenge for the Davison killing. The Chief Constable believed that IRA members collaborated with Action Against Drugs, but without the sanction of the IRA.[146] In response, the UK government commissioned the Assessment on Paramilitary Groups in Northern Ireland, which concluded in October 2015 that the IRA, while committed to peace, continues to exist in a reduced form.[147]

Ideology

The IRA's goal was a 32-county democratic socialist republic.[148] Richard English writes that while the IRA's adherence to socialist goals has varied according to time and place, radical ideas, specifically socialist ones, were a key part of IRA thinking.[149] Tommy McKearney states that while the IRA's goal was an all-Ireland socialist republic, there was no coherent analysis or understanding of socialism itself, other than an idea that the details would be worked out following an IRA victory.[150] This was in contrast to Official IRA and the Irish National Liberation Army, both of which adopted clearly defined Marxist positions. Similarly, the Northern Ireland left-wing politician Eamonn McCann has remarked that the Provisional IRA was considered a non-socialist IRA compared to the OIRA:

the primary reason why the Provisionals exist is that “socialism” as we presented it was shown to be irrelevant. The Provisionals are the inrush which filled the vacuum left by the absence of a socialist option.[151]

During the 1980s, the IRA's commitment to socialism became more solidified as IRA prisoners began to engage with works of political and Marxist theory by authors such as Frantz Fanon, Che Guevara, Antonio Gramsci, Ho-Chi Minh and General Giap. Members felt that an Irish version of the Tet Offensive could possibly be the key to victory against the British, pending on the arrival of weapons secured from Libya. However, this never came to pass, and in 1990, the fall of the Berlin wall brought a dogmatic commitment to socialism back into question, as possible Socialist allies in Eastern Europe wilted away.[152] In the years that followed, with the hopes of a military victory fading and the peace process building momentum, the IRA began to look towards South African politics and the example being set by the African National Congress. Many of the imprisoned IRA members saw parallels between their own struggle and that of Nelson Mandela and were encouraged by Mandela's use of compromise following his ascent to power in South Africa to consider compromise themselves.[152]

Weaponry and operations

In the early days of the Troubles the IRA was very poorly armed, mainly with old World War II weaponry such as M1 Garands and Thompson submachine guns, but starting in the early 1970s it procured large amounts of modern weaponry from such sources as supporters in the United States, Libyan leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi,[109] and arms dealers in Europe, North America, the Middle East and elsewhere. The Libyans supplied the IRA with the RPG-7 rocket launcher.

In the first years of the conflict, the IRA's main activities were providing firepower to support nationalist rioters and defending nationalist areas from attacks. The IRA gained much of its support from these activities, as they were widely perceived within the nationalist community as being defenders of Irish nationalist and Roman Catholic people against aggression.[153]

From 1971 to 1994, the IRA launched a sustained offensive armed campaign that mainly targeted the British Army, the RUC, the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) and economic targets in Northern Ireland. The IRA was chiefly active in Northern Ireland, although it took its campaign to England and mainland Europe. The IRA also targeted certain British government officials, politicians, judges, establishment figures, British Army and police officers in England, and in other areas such as the Republic of Ireland, West Germany, and the Netherlands. By the early 1990s, the bulk of the IRA activity was carried out by the South Armagh Brigade, well known through its sniping operations and attacks on British Army helicopters. The bombing campaign principally targeted political, economic and military targets, and was described by Andy Oppenheimer as "the biggest terrorist bombing campaign in history".[154] In the early 1990s the IRA intensified the bombing campaign in England, planting 15 bombs in 1990, 36 in 1991, and 57 in 1992.[155] The Baltic Exchange bombing in April 1992 killed three people and caused an estimated £800 million worth of damage, £200 million more than the total damage caused by the Troubles in Northern Ireland up to that point.[156][157] This was followed by the Bishopsgate bombing in 1993 which killed one person and caused an estimated £1 billion worth of damage.[158] It has been argued that this bombing campaign helped convince the British government (who had hoped to contain the conflict to Northern Ireland with its Ulsterisation policy) to negotiate with Sinn Féin.[159]

By the 1990s the IRA had become skilled in using mortars and were on a level that was comparable to military models. Seven IRA mortar attacks resulted in fatalities or serious injuries. The IRA's development of mortar tactics was a response to the heavy fortifications on RUC and British Army bases. Mortars were useful to the IRA as they could hit targets at short range, which could lead to effective attacks in built-up urban areas. The mortars used by the IRA were often self-made and developed by GHQ's engineering department.[160]

Other activities

Apart from its armed campaign, the IRA has also been involved in many other activities.

Sectarian attacks

The IRA publicly condemned sectarianism and sectarian attacks.[161] However, some IRA members did carry out sectarian attacks.[161] Of those killed by the IRA, Sutton classifies 130 (about 7%) of them as sectarian killings of Protestants.[162] Unlike loyalists, the IRA denied responsibility for sectarian attacks and the members involved used cover names, such as "Republican Action Force".[163] They stated that their attacks on Protestants were "retaliation" for attacks on Catholics.[161] Many in the IRA opposed these sectarian attacks, but others deemed them effective in preventing similar attacks on Catholics.[164] Professor Robert White writes the IRA was "in general, was not a sectarian organization",[165] and Rachel Kowalski writes that the IRA acted "in a fashion that was, for the most part, blind to religious diversity".[166]

Some unionists allege that the IRA took part in "ethnic cleansing" of the Protestant minority in rural border areas, such as Fermanagh.[167][168] Many local Protestants allegedly believed that the IRA tried to force them into leaving. However, most Protestants killed by the IRA in these areas were members of the security forces, and there was no exodus of Protestants.[169]

Alleged involvement in crime

To fund its campaign, the IRA was allegedly involved in criminal activities such as robberies, counterfeiting, protection rackets, kidnapping for ransom, fuel laundering and cigarette smuggling.[170][171][172][173] The IRA also raised funds through donations and by running legitimate businesses such as taxi firms, social clubs, pubs and restaurants. It is estimated that, by the 1990s, the IRA needed £10.5 million a year to operate.[174]

IRA supporters argue that the IRA's "securing of funds by extralegal methods is justified as a means to achieve a political goal. Unlike crimes committed for personal gain, IRA operations are considered strategic attacks against an oppressive state".[170] However, this activity allowed the British Government to portray the IRA as no more than a criminal gang.[170]

It was estimated that the IRA carried out 1,000 armed robberies in Northern Ireland, mostly of banks and post offices.[170] It was accused of involvement in the biggest bank raid in Irish history—the 2004 Northern Bank robbery—when £26.5 million was stolen.[175] The PSNI, the Independent Monitoring Commission, and the British and Irish governments all accused the IRA of involvement.[176][177] It is suggested that the IRA needed the money to pay pensions to its volunteers, and to ensure that hardliners stuck with the peace strategy.[170] The IRA denied involvement, however.[178]

Generally, the IRA was against drug dealing and prostitution, because it would be unpopular within Catholic communities and for moral reasons.[179] The Chief of the RUC's Drugs Squad, Kevin Sheehy, said "the Provisional IRA did its best to stop volunteers from becoming directly involved [in drugs]" and noted one occasion when an IRA member caught with a small amount of cannabis was "disowned and humiliated" in his local area.[180] The IRA often targeted drug dealers. Many were given punishment shootings or banished, and some were killed. However, there are claims the IRA "licensed" certain dealers to operate and forced them to pay protection money.[171][181]

Following the murder of Robert McCartney, the IRA expelled three IRA volunteers.[182] Gerry Adams said at Sinn Féin's 2005 ard fheis "There is no place in republicanism for anyone involved in criminality", while adding "we refuse to criminalise those who break the law in pursuit of legitimate political objectives".[183] This was echoed shortly after by an IRA statement issued at Easter, saying that criminality within the ranks would not be tolerated.[184] In 2008, the Independent Monitoring Commission stated that the IRA was no longer involved in criminality, but that some members have engaged in criminality for their own ends, without the sanction or support of the IRA.[185]

Vigilantism

During the conflict, the IRA took on the role of policing in some Catholic/nationalist areas of Northern Ireland.[186] Many Catholics/nationalists did not trust the official police force—the Royal Ulster Constabulary—and saw it as biased against their community.[186][187] The RUC found it difficult to operate in certain nationalist neighbourhoods and only entered in armoured convoys, due to the threat of attack from rioters and the IRA. In these neighbourhoods, many residents expected the IRA to act as a policing force,[186][188] and such policing "provided the IRA a certain propaganda value".[189] The IRA also sought to minimize contact between residents and the RUC, because residents might pass on information or be forced to become a police informer.[186] The IRA set up arbitration panels that would adjudicate and investigate complaints from locals about criminal or 'anti-social' activities.[190] Those responsible for minor offences would be given a warning, be made to compensate the offendee or be made to do community work. Those responsible for more serious and repeat offences could be given a punishment beating or kneecapping, or be banished from the community. No punishment attacks have been officially attributed to the IRA since February 2006.[191]

The IRA's vigilantism has been repeatedly condemned as "summary justice". However, on several occasions, the British authorities have recognized the IRA's policing role.[192] In January 1971, the IRA and British Army held secret talks aimed at stopping persistent rioting in Ballymurphy. It was agreed that the IRA would be responsible for policing there, but the agreement was short-lived.[193][194] During the 1975 ceasefire, the government agreed to the setting up of 'incident centres' in nationalist areas. They were staffed by Sinn Féin members and were to deal with incidents that might endanger the truce. Residents went there to report crime as well as to make complaints about the security forces. The incident centres were seen by locals as 'IRA police stations' and gave some legitimacy to the IRA as a policing force.[192]

Political opponents accused the IRA and Sinn Féin of a coverup. The Sinn Féin leader apologized to victims who were "let down" by the IRA and admitted it "was ill-equipped to deal with such matters".[195][196][197]

Informers

Throughout the Troubles, some members of the IRA passed information to the security forces. In the 1980s, many IRA members were arrested after being implicated by former IRA members known as "supergrasses" such as Raymond Gilmour.[n 8][200]

A Belfast newspaper has claimed that secret documents show that half of the IRA's top men were also British informers.[201] There have been some high-profile allegations of senior IRA figures having been British informers. In May 2003, an American website named Freddie Scappaticci as being Stakeknife.[202] Scappaticci was said to be a high-level IRA informer working for the British Army's Force Research Unit, while he was head of the IRA's Internal Security Unit, which interrogated and killed suspected informers.[203] Scappaticci denies being Stakeknife, and involvement in IRA activity.[203] In December 2005, Sinn Féin member and former IRA volunteer Denis Donaldson appeared at a press conference in Dublin and confessed to being a British spy since the early 1980s.[204][205] Donaldson, who ran Sinn Féin's operations in New York during the Northern Ireland peace process, was expelled by the party.[204][206] On 4 April 2006, Donaldson was found shot dead at his retreat near Glenties in County Donegal.[207] The Real IRA claimed responsibility for his assassination on 12 April 2009.[208] Other prominent informers include Eamon Collins,[199] Sean O'Callaghan,[209] and Roy McShane, who worked as a driver for the leadership of Sinn Féin including Gerry Adams.[206][210]

The IRA took a hard line against anyone believed to be secretly passing information about IRA activity to British forces. The IRA regarded them as traitors,[211] and a threat to the organisation and lives of its members.[212] Suspected informers were dealt with by the IRA's Internal Security Unit (ISU). It carried out an investigation, and interrogated the suspect. Following this a court martial would take place, consisting of three members of equal or higher rank than the accused, plus a member of GHQ or the Army Council acting as an observer.[213] Any death sentence would be ratified by the Army Council, who would be informed of the verdict by the observer.[213] IRA members who confessed to being informers were killed with a shot to the head. Civilian informers were regarded as collaborators and were usually either killed or exiled. The IRA killed 59 alleged informers, about half of them IRA members and half of them Catholic civilians. The bodies of alleged informers were usually left in public as a warning to others. Twelve, however, were secretly buried and became known as "the Disappeared".

One particularly controversial killing of an alleged informer was that of Jean McConville. A Catholic civilian and widowed mother-of-ten, her body was secretly buried and not found until thirty years later. The IRA has since issued a general apology, saying it "regrets the suffering of all the families whose loved ones were killed and buried by the IRA".[214]

The original IRA, as well as loyalist paramilitaries, also had a policy of killing alleged informers.[215]

Conflict with other republican paramilitaries

The IRA has also feuded with other republican paramilitary groups such as the Official IRA in the 1970s and the Irish People's Liberation Organisation in the 1990s.

Leading Real Irish Republican Army member Joseph O'Connor was shot dead in Ballymurphy, west Belfast on 11 October 2000.[216] Claims have been made by O'Connor's family and others including Marian Price and Anthony McIntyre that he was killed by the IRA,[216] but Sinn Féin denied the claims as did the IRA.[217][218] No-one has been charged with his killing.

Casualties

The IRA was responsible for more deaths than any other organisation during the Troubles.[219] Two detailed studies of deaths in the Troubles, the Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN), and the book Lost Lives, differ slightly on the numbers killed by the IRA and the total number of conflict deaths. According to CAIN, the IRA was responsible for at least 1,705 deaths, about 48% of the total conflict deaths.[220] Of these, at least 1,009 (about 59%) were members or former members of the British security forces, while at least 508 (about 29%) were civilians.[20] According to Lost Lives (2004 edition), the IRA was responsible for 1,781 deaths, about 47% of the total conflict deaths. Of these, 944 (about 53%) were members of the British security forces, while 644 (about 36%) were civilians (including 61 former members of the security forces).[21] The civilian figure also includes civilians employed by British forces, politicians, members of the judiciary, and alleged criminals and informers. Most of the remainder were loyalist or republican paramilitary members; including over 100 IRA members accidentally killed by their own bombs or shot for being security force agents or informers. Overall, the IRA was responsible for 87–90% of the total British security force deaths, and 27–30% of the total civilian deaths in the conflict.[20][21] During the IRA's campaign in England it was responsible for at least 488 incidents causing 2,134 injuries and 115 deaths, including 56 civilians and 42 British Army soldiers.[n 9][223][224] 275–300 IRA members were killed in the Troubles.[22][23] In addition, roughly 50–60 members of Sinn Féin were killed.[225]

Categorisation

The IRA is a proscribed organisation in the United Kingdom under the Terrorism Act 2000,[16] and an unlawful organisation in the Republic of Ireland under the Offences Against the State Acts, where IRA volunteers are tried in the non-jury Special Criminal Court.[n 10][17] The IRA rejected the authority of the courts in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and its standing orders did not allow volunteers on trial in a criminal court to enter a plea or recognise the authority of the court, doing so could lead to expulsion from the IRA.[n 11][227][228] These orders were relaxed in 1976 due to increased sentences in the Republic of Ireland for IRA membership.[227] IRA prisoners were granted conditional early release as part of the Good Friday Agreement.[229][230]

The US Department of State has not designated the IRA as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, but lists them in the category 'other selected terrorist groups also deemed of relevance in the global war on terrorism'.[231][232] American media tended to describe the Provisional IRA as "activists" and "guerrillas", while the British counterpart commonly used the term "terrorists", particularly the BBC as part of its official guidelines, published in 1989.[233] Republicans reject the label of terrorism, instead describing the IRA's activity as war, military activity, armed struggle or armed resistance.[234] The IRA prefer the terms freedom fighter, soldier, activist, or volunteer for its members.[235][236][237] The IRA has also been described as a "private army".[238][239] The IRA sees the Irish War of Independence as a guerrilla war which accomplished some of its aims, with some remaining "unfinished business".[240][241]

An internal British Army document written by General Sir Michael David Jackson and two other senior officers was released in 2007 under the Freedom of Information Act.[242] It examined the British Army's 37 year of deployment in Northern Ireland, and described the IRA as "a professional, dedicated, highly skilled and resilient force", while loyalist paramilitaries and other republican groups were described as "little more than a collection of gangsters".[242]

Strength and support

Numerical strength

It is unclear how many people joined the IRA during the troubles, however in the early to mid-1970s, the numbers recruited by the IRA may have reached several thousand. Official membership reduction coincided with the adoption by the IRA of a 'cell structure' in an attempt to counter security force penetration through the use of informers.[243] In addition to members in Ireland the IRA also had one or two 'active service units' in Britain and mainland Europe.[243]

An RUC report of 1986 estimated that the IRA had 300 or so members in active service units and up to 750 active members in total in Northern Ireland.[51] This does not take into consideration the IRA units in the Republic of Ireland or those in Great Britain, continental Europe, or elsewhere. In 2005, the then Irish Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform, Michael McDowell told the Dáil that the organisation had between 1,000 and 1,500 active members.[244]

According to the book The Provisional IRA (by Eamon Mallie and Patrick Bishop), roughly 8,000 people passed through the ranks of the IRA in the first 20 years of its existence, many of them leaving after arrest, "retirement" or disillusionment.[24] According to Sinn Féin MLA Gerry Kelly approximately 30,000 members passed through the ranks of the IRA between 1969 and 1997 with most leaving after a short period of time.[245]

Support from other countries and organisations

The IRA have had contacts with foreign governments and other illegal armed organisations.

Libya was a supplier of arms to the IRA, donating two shipments of arms in the early 1970s,[246] and another five in the mid-1980s.[247] The final shipment in 1987 was intercepted by French authorities,[247] but the prior four shipments included 1,200 AKM assault rifles, 26 DShK heavy machine guns, 40 general-purpose machine guns, 33 RPG-7 rocket launchers, 10 SAM-7 surface-to-air missiles, 10 LPO-50 flamethrowers, and over two tonnes of Semtex, a plastic explosive.[248]

The IRA has also received weapons and financial support from Irish Americans in the United States.[249] Apart from the Libyan aid, this has been the main source of overseas IRA support. In the United States in November 1982, five men, including George Harrison and Michael Flannery, were acquitted of smuggling arms to the IRA after they claimed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had approved the shipment through arms dealer George de Meo, although de Meo denied any connection with the CIA.[250] Harrison is estimated to have smuggled 2,500 weapons and a million rounds of ammunition to Ireland, an estimate described as "conservative" by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.[251] American support was weakened by the 11 September 2001 attacks and the subsequent "War on Terror".[252]

There was contact between the IRA and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and specifically the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine starting from the mid-1970s which included the intensive training of IRA volunteers. In 1977, the Provisionals received a 'sizeable' arms shipment from the PLO, including arms, rocket launchers and explosives, but this was intercepted at Antwerp after the Israeli intelligence alerted its European counterparts. Afterwards, they declined on the grounds that it was impossible to smuggle arms out of the Levant region without alerting Israeli intelligence. Tim Pat Coogan wrote that assistance from the PLO has dried up in the late-1980s after the PLO had forged stronger links with the government of the Republic of Ireland.[253]

The IRA had links with the Basque separatist group ETA.[249] Maria McGuire states the IRA received fifty revolvers from ETA in exchange for explosives training.[254][255] In 1973 it was accused by the Spanish police of providing explosives for the assassination of Spanish prime minister Luis Carrero Blanco in Madrid, and the following year an ETA spokesman told German magazine Der Spiegel they had "very good relations" with the IRA.[249][254] In 1977 a representative of the Basque political party Euskal Iraultzarako Alderdia attended Sinn Féin's 1977 ard fheis, and Ruairí Ó Brádaigh had a close relationship with Basque separatists, regularly visiting the Basque region between 1977 and 1983.[256]

In May 1996, the Federal Security Service (FSB), Russia's internal security service, accused Estonia of arms smuggling, and claimed that the IRA had bought weapons from arms dealers linked to Estonia's volunteer defence force, Kaitseliit.[257] In 2001, three Irish men, who later became known as the Colombia Three, were arrested after allegedly training Colombian guerrillas, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), in bomb making and urban warfare techniques. The US House of Representatives Committee on International Relations in its report of 24 April 2002 concluded "Neither committee investigators nor the Colombians can find credible explanations for the increased, more sophisticated capacity for these specific terror tactics now being employed by the FARC, other than IRA training".[258]

See also

Notes

- Irish republicans do not recognise any of the Irish states since 1922, but declare their allegiance to the Republic of 1919–22.[2]

- In addition to the scheduled General Army Convention, the Executive, by a majority vote of its 12 members, had the power to order an Extraordinary General Army Convention, which would be attended by the delegates of the previous General Army Convention, where possible.[26]

- The Executive elected in September 1970 remained in place until 1986, filling vacancies by co-option when necessary.[35]

- The vote was a show of hands and the result is disputed.[83] It has been variously reported as twenty-eight votes to twelve,[80] or thirty-nine votes to twelve.[84] The official minutes state out of the forty-six delegates scheduled to attend, thirty-nine were in attendance, and the result of the second vote was twenty-seven votes to twelve.[82]

- The Provisional IRA issued all its public statements under the pseudonym "P. O'Neill" of the "Irish Republican Publicity Bureau, Dublin".[89] Dáithí Ó Conaill, the IRA's director of publicity, came up with the name.[90] According to Danny Morrison, the pseudonym "S. O'Neill" was used during the 1940s.[89]

- In 1992 Colonel Gaddafi is understood to have given the British Government a detailed inventory of weapons he supplied to the IRA.[135]

- General de Chastelain has also stated weapons might have been lost due to a person responsible for them having died.[139] Michael McKevitt, the IRA's quartermaster-general who left to form the Real IRA, is known to have taken materiel from IRA arms dumps.[140]

- Thirty-five people implicated by Gilmour were acquitted following a six-month trial in 1984, with Lord Lowry, the Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland, describing Gilmour as a "selfish and self-regarding man to whose lips a lie invariably came more naturally than the truth".[198] While some convictions were obtained in other supergrass trials, the verdicts were overturned by Northern Ireland's Court of Appeal. This was due to convictions being based solely on the evidence of dubious witnesses, as most supergrasses were paramilitaries giving evidence in return for a shorter prison sentence or immunity from prosecution.[199]

- In addition to bombings and occasional gun attacks in England, the IRA also used hoax bomb threats to disrupt the transport infrastructure.[221] A hoax bomb threat also forced the evacuation of Aintree Racecourse, postponing the 1997 Grand National.[222]

- Prior to May 1972 IRA volunteers in the Republic of Ireland were tried in normal courts. The three judge Special Criminal Court was re-introduced following a series of regional court cases where IRA volunteers were acquitted or received light sentences from sympathetic judges and juries, and also to prevent jury tampering.[226]

- There were occasional exceptions to this, there are several instances of female IRA volunteers being permitted to ask for bail and/or present a defence. This generally happened where the volunteer had children whose father was dead or imprisoned. There are some other cases where male IRA volunteers were permitted to present a defence.[227]

References

- Moloney 2002, pp. 502–508.

- English 2003, p. 106.

- Moloney 2002, p. xiv.

- Moloney 2002, p. 98.

- English 2003, p. 103.

- Geraghty 1998, p. 180.

- White 2017, p. 392.

- Tonge & Murray 2005, p. 67.

- Bowyer Bell 1987, p. 247.

- Dillon 1996, p. 125.

- Bowyer Bell 2000, p. 1.

- Dillon 1996, p. 353.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 13.

- Moloney 2002, p. 246.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 104.

- Wilson et al. 2020, p. 128.

- Conway 2015, p. 101.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, p. 117.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 23.

- CAIN: Crosstabulations (two-way tables): "Organisation" and "Status Summary" as variables.

- McKittrick 2004, p. 1536.

- McKittrick 2004, p. 1531.

- CAIN: Status of the person killed.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, p. 12.

- Moloney 2002, pp. 378–379.

- Moloney 2002, pp. 475–476.

- English 2003, pp. 114–115.

- Moloney 2002, p. 444.

- Rowan 2003, p. 96.

- Taylor 1997, p. 357.

- Clarke & Johnston 2001, p. 232.

- Moloney 2007, p. 517.

- Clarke & Johnston 2001, p. 237.

- Harding 2002

- Bowyer Bell 1990, p. 13.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 158.

- English 2003, p. 43.

- Leahy 2020, p. 191.

- Moloney 2002, p. 157.

- Moloney 2002, pp. 155–160.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 110.

- White 2017, p. 150.

- Taylor 1997, p. 70.

- Moloney 2002, p. 210.

- Moloney 2002, p. 304.

- Moloney 2002, p. 103.

- Leahy 2020, p. 89.

- Leahy 2020, p. 130.

- Coogan 2002b, p. 465.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, p. 322.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 161.

- Moloney 2002, p. 377.

- Harnden 1999, p. 34.

- Taylor 1997, pp. 8–10.

- White 2017, p. 21.

- Taylor 1997, p. 18.

- Oppenheimer 2008, pp. 53–55.

- English 2003, pp. 67–70.

- English 2003, p. 75.

- Smith 1995, p. 72.

- Taylor 1997, p. 23.

- White 2017, p. 45.

- Shanahan 2008, p. 12.

- Dillon 1990, p. xxxvi.

- Taylor 1997, pp. 29–31.

- Taylor 1997, p. 19.

- Taylor 1997, p. 27.

- White 2017, p. 47–48.

- Taylor 1997, pp. 39–43.

- White 2017, p. 50.

- Munck 1992, p. 224.

- Taylor 1997, p. 47.

- Taylor 1997, pp. 49–50.

- Shanahan 2008, p. 13.

- Coogan 2002a, p. 91.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, pp. 108–112.

- Taylor 1997, p. 60.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, pp. 93–94.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, p. 125.

- White 2017, pp. 64–65.

- Hanley & Millar 2010, p. 145.

- Horgan & Taylor 1997, p. 152.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, p. 136.

- Bowyer Bell 1997, p. 366.

- English 2003, p. 105.

- Taylor 1997, p. 65.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, p. 141.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, p. 137.

- BBC News Magazine 2005.

- White 2006, p. 153.

- Taylor 1997, p. 67.

- Taylor 1997, pp. 104–105.

- English 2003, p. 119.

- Taylor 1997, pp. 289–291.

- Moloney 2002, p. 80.

- Nordstrom & Martin 1992, p. 199.

- Ó Dochartaigh 2005, p. 162.

- English 2003, p. 125.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, p. 40.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 119.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 107.

- Walker 1986, p. 9.

- Ó Faoleán 2019, p. 53.

- Mulroe 2017, p. 21.

- Moloney 2002, p. 180.

- Taylor 1997, p. 139.

- Taylor 2001, p. 184.

- English 2003, p. 179.

- Taylor 1997, p. 156.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 128.

- Moloney 2002, p. 182.

- Moloney 2002, p. 194.

- English 2003, p. 200.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 127.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 270.

- Taylor 1997, pp. 301–312.

- O'Brien 1999, pp. 293–294.

- O'Brien 1999, pp. 209–212.

- Taylor 1997, p. 379.

- Taylor 1997, p. 380.

- Moloney 2002, p. 346.

- Moloney 2002, p. 423.

- Tonge 1996, p. 168.

- Rowan 2003, pp. 36–37.

- Moore 2006, p. 90.

- Rowan 2003, p. 27.

- Rowan 2003, pp. 15–16.

- Rowan 2003, p. 30.

- Boyne 2006, pp. 406–407.

- Boyne 2006, p. 408.

- Boyne 2006, p. 403.

- Frampton 2009, p. 169.

- Boyne 2006, p. 409.

- Oppenheimer 2008, p. 347.

- Boyne 2006, pp. 391–393.

- Boyne 2006, p. 412.

- Boyne 2006, pp. 412–413.

- Boyne 2006, p. 414.

- Boyne 2006, p. 424.

- Boyne 2006, p. 423.

- Saunders 2012, p. 201.

- Saunders 2012, p. 209.

- Horgan 2013, p. 39.

- White 2017, p. 382.

- "'No info' provos involved in crimes". Irish Independent, 28 February 2015.

- "Chief Constable's statement – PSNI's assessment of the current status of the Provisional IRA". Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI). 22 August 2015.

- Armstrong, Herbert & Mustad 2019, p. 24.

- White 2017, p. 337.

- English 2003, p. 369.

- McKearney 2011, p. 105.

- McCann 1993, p. 299.

- Reinisch, Dieter (7 September 2018). "Dreaming of an "Irish Tet Offensive": Irish Republican prisoners & the origins of the Peace Process". me.eui.eu. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- English 2003, pp. 134–135.

- Oppenheimer 2009, p. 43.

- White 2017, p. 264.

- White 2017, p. 266.

- Taylor 1997, p. 327.

- Taylor 1997, pp. 334–335.

- Leahy 2020, pp. 195–196.

- Ackerman 2016, pp. 12–34.

- English 2003, p. 173.

- Sutton, Malcolm. Revised and Updated Extracts from Sutton's Book. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

- McKittrick & McVea 2012, p. 115.

- Coogan 2002b, p. 443.

- White 1997, pp. 20–55.

- Kowalski 2018, pp. 658–683.

- "IRA border campaign 'was ethnic cleansing'". The News Letter. 19 March 2013.

- "Jim Cusack: IRA engaged in 'ethnic cleansing' of Protestants along Border". Irish Independent. 24 March 2013.

- "Border Killings – Liberation Struggle or Ethnic Cleansing?" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. University of Ulster news release. 29 May 2006.

- Connelly 2012, p. 204.

- David Lister & Sean O'Neill (25 February 2005). "IRA plc turns from terror into biggest crime gang in Europe". The Times. London.

- Jim Cusack (28 December 2008). "Fuel-laundering still in full swing". Irish Independent.

- Diarmaid MacDermott & Bronagh Murphy (14 June 2008). "IRA kidnap gang 'captured' seven Gardaí and soldiers". Irish Independent.

- Biersteker, Eckert & Williams 2007, p. 137.

- Moore 2006, pp. 25–26.

- Moore 2006, p. 35–36.

- White 2017, p. 322.

- Moore 2006, p. 88.

- Dingley 2012, p. 197.

- Sheehy 2008, p. 94.

- Horgan & Taylor 1999, p. 29.

- Moore 2006, pp. 114–115.

- Frampton 2009, pp. 161–162.

- Moore 2006, pp. 124–126.

- Independent Monitoring Commission (3 September 2008). "Twelfth report of the Independent Monitoring Commission" (PDF). The Stationery Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Weitzer 1995, pp. 157–158.

- Taylor 2001, p. 22.

- Eriksson 2009, pp. .39–40

- Goodspeed 2001, p. .80

- Hamill 2010, pp. 33–34.

- Sinclair & Antonius 2013, p. .149

- Findlay 1993, p. 146.

- Reed 1984, pp. 158–159.

- Moloney 2002, p. 95.

- "Paramilitaries shot and exiled many alleged sex abusers". The Irish Times. 30 October 2014.

- "Gerry Adams says IRA 'let down' sex abuse victims". BBC News. 22 October 2014.

- "Extraordinary scenes in Dail as Taoiseach challenges Gerry Adams on abuse". Irish Independent. 22 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- Taylor 1997, p. 264.

- Leahy 2020, p. 124.

- Taylor 1997, pp. 259–260.

- "Half of all top IRA men 'worked for security services'".

- Ingram & Harkin 2004, p. 241.

- Leahy 2020, p. 2.

- White 2017, p. 360.

- Boyne 2006, pp. 177–178.

- Leahy 2020, p. 229.

- Clancy 2010, p. 160.

- White 2017, p. 377.

- Leahy 2020, p. 191.

- White 2017, p. 361.

- Bowyer Bell 2000, p. 250.

- Bowyer Bell 2000, p. 69.

- Taylor 1993, p. 153.

- McDonald, Henry (9 July 2006). "IRA told: end lies about 'disappeared' mother". The Observer. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Melaugh, Martin. Killings of Alleged Informers, Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN); accessed 5 May 2014.

- English 2003, p. 320.

- "IRA denies murdering dissident". BBC News. 18 October 2000. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- Rowan 2003, p. 190.

- English 2003, p. 378.

- CAIN: Organisation Responsible for the death.

- McGladdery 2006, p. 153.

- McGladdery 2006, p. 207.

- McGladdery 2006, p. 3.

- CAIN: Select and Crosstabulations: "Geographical Location: Britain", "Organisation" and "Status" as variables.

- O'Brien 1999, p. 26.

- Ó Faoleán 2019, p. 86–88.

- Ó Faoleán 2019, pp. 135–137.

- Moloney 2002, p. 56.

- English 2003, pp. 324–325.

- Horgan 2013, p. 136.

- Toby Harnden (17 May 2001). "Real IRA designated terrorists". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "U.S. Department of Homeland Security – Terrorist Organization Reference Guide January 2004, p119" (PDF).

- Aldridge & Hewitt 1994, pp. 72–73.

- Shanahan 2008, p. 4.

- Jackson, Breen Smyth & Gunning 2009, p. 142.

- Hayes 1980, p. 77.

- O'Sullivan 1986, p. 104.

- White 2017, p. 306.

- English 2003, pp. 161–162.

- O'Brien 1999, pp. 22–23.

- Shanahan 2008, p. 46.

- Quilligan 2013, pp. 280–282.

- Melaugh, Dr Martin. "CAIN: Issues: Violence – Paramilitary Groups, Membership and Arsenals". Conflict Archive on the Internet.

- Oireachtas, Houses of the (23 June 2005). "Dáil Éireann debate - Thursday, 23 Jun 2005". www.oireachtas.ie.

- Vadio IE (26 June 2015). "MLA Gerry Kelly – 10th October 2013" – via YouTube.

- Boyne 2006, pp. 137–138.

- Boyne 2006, pp. 272–274.

- Boyne 2006, p. 436.

- Coogan 2002b, p. 436.

- Boyne 2006, p. 201.

- Taylor 1997, p. 1.

- Cochrane 2007, p. 225.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, p. 307.

- Geraghty 1998, pp. 177–178.

- Mallie & Bishop 1988, p. 308.

- White 2006, p. 262.

- Boyne 2006, p. 396.

- "Report". U.S. House of Representatives House International Relations Committee. 24 April 2002. Archived from the original on 28 February 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

Bibliography

- Ackerman, Gary. A (2016). "The Provisional Irish Republican Army and the Development of Mortars". Journal of Strategic Security. 9 (1). doi:10.5038/1944-0472.9.1.1501 – via Scholar Commons.

- Aldridge, Meryl; Hewitt, Nicholas (1994). Controlling Broadcasting: Access Policy and Practice in North America and Europe. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719042775.

- Armstrong, Charles I.; Herbert, David; Mustad, Jan Erik (2019). The Legacy of the Good Friday Agreement: Northern Irish Politics, Culture and Art after 1998. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3319912318.

- BBC News Magazine (28 September 2005). "Who is P O'Neill?". BBC News. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Bew, Paul; Gillespie, Gordon (1993). Northern Ireland: A Chronology of the Troubles, 1968-93. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0717120819.

- Biersteker, Thomas J.; Eckert, Sue E.; Williams, Phil (2007). Countering the Financing of Terrorism. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415396431.

- Bowyer Bell, J. (1987). The Gun in Politics: Analysis of Irish Violence, 1916–86. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56000-566-7.

- Bowyer Bell, J. (1990). IRA: Tactics & Targets. Poolbeg. ISBN 1-85371-257-4.

- Bowyer Bell, J. (1997). The Secret Army: The IRA. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-901-2.

- Bowyer Bell, J. (2000). The IRA, 1968-2000: An Analysis of a Secret Army. Routledge. ISBN 978-0714681191.

- Boyne, Sean (2006). Gunrunners: The Covert Arms Trail to Ireland. O'Brien Press. ISBN 0-86278-908-7.

- Clancy, Mary Alice C. (2010). Peace Without Consensus: Power Sharing Politics in Northern Ireland. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0754678311.

- Clarke, Liam; Johnston, Kathryn (2001). Martin McGuinness: From Guns to Government. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 9-781840-184730.

- Cochrane, Feargal (2007). "Irish-America, the End of the IRA's Armed Struggle and the Utility of 'Soft Power'". Journal of Peace Research. 44 (2). JSTOR 27640484.

- Connelly, Mark (2012). The IRA on Film and Television: A History. McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0786447367.

- Conway, Vicky (2015). Policing Twentieth Century Ireland: A History of An Garda Síochána. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138899988.

- Coogan, Tim Pat (2002a). The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal and the Search for Peace. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0312294182.

- Coogan, Tim Pat (2002b). The I.R.A. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0312294168.

- Dillon, Martin (1990). The Dirty War. Arrow Books. ISBN 0-09-984520-2.

- Dillon, Martin (1996). 25 Years of Terror: The IRA's war against the British. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-40773-0.

- Dingley, James (2012). The IRA: The Irish Republican Army. Praeger Publishing. ISBN 978-0313387036.

- English, Richard (2003). Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA. Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-49388-4.

- Eriksson, Anna (2009). Justice in Transition: Community restorative justice in Northern Ireland. Willan Publishing. ISBN 978-1843925187.

- Findlay, Mark (1993). Alternative Policing Styles:Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Springer. ISBN 978-9065447104.

- Frampton, Martyn (2009). The Long March: The Political Strategy of Sinn Féin, 1981-2007. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230202177.

- Geraghty, Tony (1998). The Irish War: The Military History of a Domestic Conflict. Fire and Water. ISBN 978-0-00-638674-2.

- Goodspeed, Michael (2001). When Reason Fails: Portraits of Armies at War - America, Britain, Israel and the Future (Studies in Military History and International Affairs). Praeger. ISBN 978-0275973780.

- Hamill, Heather (2010). The Hoods: Crime and Punishment in Belfast: Crime and Punishment in West Belfast. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691119632.

- Hanley, Brian; Millar, Scott (2010). The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0141028453.

- Harding, Thomas (9 September 2002). "IRA's hardline faction gets a stronger voice". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Harnden, Toby (1999). Bandit Country: The IRA & South Armagh. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-71736-X.

- Hayes, David (1980). Terrorists and Freedom Fighters : People, Politics and Powers Series. Main Line Book Co. ISBN 978-0853406525.

- Horgan, John; Taylor, Max (1997). "Proceedings of the Irish Republican Army General Army Convention, December 1969". Terrorism and Political Violence. 9 (4). doi:10.1080/09546559708427434.

- Horgan, John; Taylor, Max (1999). "Playing the 'Green Card' - Financing the Provisional IRA: Part 1" (PDF). Terrorism and Political Violence. 11 (2). doi:10.1080/09546559908427502. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2009.

- Horgan, John (2013). Divided We Stand: The Strategy and Psychology of Ireland's Dissident Terrorists. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199772858.

- Ingram, Martin; Harkin, Greg (2004). Stakeknife: Britain's Secret Agents in Ireland. O'Brien Press. ISBN 978-0862788438.

- Jackson, Richard; Breen Smyth, Marie; Gunning, Jeroen (2009). Critical Terrorism Studies: A New Research Agenda. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415455077.

- Kowalski, Rachel Caroline (2018). "The role of sectarianism in the Provisional IRA campaign, 1969–1997". Terrorism and Political Violence. 30 (4). doi:10.1080/09546553.2016.1205979.

- Leahy, Thomas (2020). The Intelligence War against the IRA. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108487504.

- McCann, Eamonn (1993). War and an Irish Town. Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745307251.

- McGladdery, Gary (2006). The Provisional IRA in England: The Bombing Campaign 1973–1997. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 9780716533733.

- McKearney, Tommy (2011). The Provisional IRA: From Insurrection to Parliament. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-3074-7.

- McKittrick, David (2004). Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children Who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1840185041.

- McKittrick, David; McVea, David (2012). Making Sense of the Troubles: A History of the Northern Ireland Conflict. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0241962657.

- Mallie, Eamonn; Bishop, Patrick (1988). The Provisional IRA. Corgi Books. ISBN 0-7475-3818-2.

- Moloney, Ed (2002). A Secret History of the IRA. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-101041-0.

- Moloney, Ed (2007). A Secret History of the IRA (2nd edition). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0141028767.

- Moore, Chris (2006). Ripe for the Picking: The Inside Story of the Northern Bank Robbery. Gill & MacMillan. ISBN 0-7171-4001-6.

- Mulroe, Patrick (2017). Bombs, Bullets and the Border: Policing Ireland’s Frontier. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-1911024491.

- Munck, Ronnie (1992). "The Making of the Troubles in Northern Ireland". Journal of Contemporary History. 27 (2). ISSN 0022-0094.

- Nordstrom, Carolyn; Martin, JoAnn (1992). The Paths to Domination, Resistance, and Terror. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520073166.

- O'Brien, Brendan (1999). The Long War – The IRA and Sinn Féin. O'Brien Press. ISBN 0-86278-606-1.

- Ó Dochartaigh, Niall (2005). From Civil Rights to Armalites. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-4431-3.

- Ó Faoleán, Gearóid (2019). A Broad Church: The Provisional IRA in the Republic of Ireland, 1969–1980. Merrion Press. ISBN 978-1785372452.

- O'Sullivan, Noël (1986). Terrorism, Ideology And Revolution: The Origins Of Modern Political Violence. Routledge. ISBN 978-0367289928.

- Oppenheimer, A.R. (2008). IRA: The Bombs and the Bullets: A History of Deadly Ingenuity. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-0716528951.

- Oppenheimer, Andy (2009). "IRA Technology". The Counter Terrorist. 2 (4). ISSN 1941-8639.

- Quilligan, Michael (2013). Understanding Shadows: The Corrupt Use of Intelligence. Clarity Press Inc. ISBN 978-0985335397.

- Reed, David (1984). Ireland: The Key to the British Revolution. Larkin Publication. ISBN 978-0905400044.

- Rowan, Brian (2003). The Armed Peace: Life and Death after the Ceasefires. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-84018-754-9.

- Saunders, Andrew (2012). Inside The IRA: Dissident Republicans And The War For Legitimacy. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4696-8.

- Shanahan, Timothy (2008). The Provisional Irish Republican Army and the Morality of Terrorism. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748635306.

- Sheehy, Kevin (2008). More Questions Than Answers: Reflections on a Life in the RUC. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0717143962.

- Sinclair, Samuel Justin; Antonius, Daniel (2013). The Political Psychology of Terrorism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199925926.

- Smith, M.L.R. (1995). Fighting for Ireland: The Military Strategy of the Irish Republican Movement. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415091619.

- Sutton, Malcolm. "Sutton Index of Deaths: Crosstabulations (two-way tables)". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Sutton, Malcolm. "Sutton Index of Deaths: Organisation responsible for the death". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Sutton, Malcolm. "Sutton Index of Deaths: Select and Crosstabulations". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Sutton, Malcolm. "Sutton Index of Deaths: Status of the person killed". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Taylor, Peter (1993). States of Terror. BBC. ISBN 0-563-36774-1.

- Taylor, Peter (1997). Provos The IRA & Sinn Féin. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 0-7475-3818-2.

- Taylor, Peter (2001). Brits. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-5806-4.

- Tonge, Johnathan (1996). Northern Ireland: Conflict and Change. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-42400-5.

- Tonge, Jonathan; Murray, Gerard (2005). Sinn Féin and the SDLP: From Alienation to Participation. C Hurst & Co Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-649-4.

- Walker, Clive (1986). The Prevention of Terrorism in British Law. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7475-5806-4.