Hammersmith

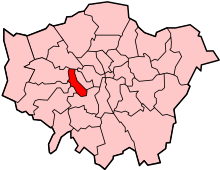

Hammersmith is a district of west London, England, located 4.3 miles (6.9 km) west-southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, and identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

| Hammersmith | |

|---|---|

Lyric Theatre | |

Hammersmith Location within Greater London | |

| OS grid reference | TQ233786 |

| • Charing Cross | 4.3 mi (6.9 km) ENE |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | W6 W14 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

It is bordered by Shepherd's Bush to the north, Kensington to the east, Chiswick to the west, and Fulham to the south, with which it forms part of the north bank of the River Thames. It is linked by Hammersmith Bridge to Barnes in the southwest. The area is one of west London's main commercial and employment centres, and has for some decades been a major centre of London's Polish community. It is a major transport hub for west London, with two London Underground stations and a bus station at Hammersmith Broadway.

History

Hammersmith originally meant "(Place with) a hammer smithy or forge",[1] first recorded in 1294.[1] Hammersmith is in the historic county of Middlesex. It was the name of a parish, and of a suburban district, within the hundred of Osselstone.[2] In the early 1660s, Hammersmith's first parish church, which later became St Paul's, was built by Sir Nicholas Crispe who ran the brickworks in Hammersmith.[3] It contained a monument to Crispe as well as a bronze bust of King Charles I by Hubert Le Sueur.[4] In 1696 Sir Samuel Morland was buried there. The church was completely rebuilt in 1883, but the monument and bust were transferred to the new church.

Hammersmith Bridge was first designed by William Tierney Clark, opening in 1827 as the first suspension bridge crossing the River Thames. Overloading in this original structure led to a redesign by Joseph Bazalgette, which was built over the original foundations, and reopened in 1887.[3][5] In 1984–1985 the bridge received structural support, and between 1997 and 2000 the bridge underwent major strengthening work.[6]

In 1745, two Scots, James Lee and Lewis Kennedy, established the Vineyard Nursery, over six acres devoted to landscaping plants. During the next hundred and fifty years the nursery introduced many new plants to England, including fuchsia and the standard rose tree.[7][8]

Major industrial sites included the Osram lamp factory at Brook Green, the J. Lyons factory (which at one time employed 30,000 people). During both World Wars, Waring & Gillow's furniture factory, in Cambridge Grove, became the site of aircraft manufacture.

Hammersmith Borough Council had provided the borough with electricity since the early twentieth century from Hammersmith power station. Upon nationalisation of the electricity industry in 1948 ownership passed to the British Electricity Authority and later to the Central Electricity Generating Board. Electricity connections to the national grid rendered the 20 megawatt (MW) coal-fired power station redundant. It closed in 1965; in its final year of operation it delivered 5,462 MWh of electricity to the borough.[9]

Economy

Hammersmith is located at the confluence of one of the arterial routes out of central London (the A4) with several local feeder roads and a bridge over the Thames. The focal point of the district is the commercial centre (the Broadway Centre) located at this confluence, which houses a shopping centre, bus station, an Underground station and an office complex.

Stretching about 750 m (820 yd) westwards from this centre is King Street, Hammersmith's main shopping street. Named after John King, Bishop of London,[10] it contains a second shopping centre (Kings Mall), many small shops, the Town Hall, the Lyric Theatre, a cinema, the Polish community centre and two hotels. King Street is supplemented by other shops along Shepherds Bush Road to the north, Fulham Palace Road to the south and Hammersmith Road to the east. Hammersmith's office activity takes place mainly to the eastern side of its centre, along Hammersmith Road and in the Ark, an office complex to the south of the flyover which traverses the area.

Charing Cross Hospital on Fulham Palace Road is a large multi-disciplinary NHS hospital with accident & emergency and teaching departments run by the Imperial College School of Medicine.[11]

Architecture

"The Ark" office building, designed by British architect Ralph Erskine and completed in 1992, has some resemblance to the hull of a sailing ship.[12] Hammersmith Bridge Road Surgery was designed by Guy Greenfield.[13] "22 St Peter's Square" the former Royal Chiswick Laundry and Island Records HQ converted to architects studios and offices by Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands. It has a Hammersmith Society Conservation award plaque (2009)[14] and has been included in tours in Architecture Week.[15] Several of Hammersmith's pubs are listed buildings, including the Black Lion,[16] The Dove,[17] The George,[18] The Hop Poles,[19] the Hope and Anchor,[20] the Salutation Inn[21] and The Swan,[22] as are Hammersmith's two parish churches, St Paul's[23] (the town's original church, rebuilt in the 1890s) and St Peter's, built in the 1820s.[24]

Culture and entertainment

Riverside Studios is a cinema, performance space, bar and cafe. Originally film studios, Riverside Studios were used by the BBC from 1954 to 1975 for television productions.[25] The Lyric Hammersmith Theatre is just off King Street. Hammersmith Apollo concert hall and theatre (formerly the Carling Hammersmith Apollo, the Hammersmith Odeon, and before that the Gaumont Cinema) is just south of the gyratory. The former Hammersmith Palais nightclub has been demolished and the site reused as student accommodation. The Polish Social and Cultural Association is on King Street. It contains a theatre, an art gallery and several restaurants. Its library has one of the largest collections of Polish-language books outside Poland.[26][27][28][29][30]

The Dove is a riverside pub with what the Guinness Book of Records listed as the smallest bar room in the world, in 2016 surviving as a small space on the right of the bar.[31] the pub was frequented by Ernest Hemingway and Graham Greene; James Thomson lodged and likely wrote Rule Britannia here.[32] The narrow alley in which it stands is the only remnant of the riverside village of Hammersmith, the bulk of which was demolished in the 1930s. Furnivall Gardens, which lies to the east, covers the site of Hammersmith Creek and the High Bridge.[33] Leisure activity also takes place along Hammersmith's pedestrianised riverside, home to pubs, rowing clubs and the riverside park of Furnival Gardens. Hammersmith has a municipal park, Ravenscourt Park, to the west of the centre. Its facilities include tennis courts, a basketball court, a bowling lawn, a paddling pool and playgrounds.[34]

Hammersmith is the historical home of the West London Penguin Swimming and Water Polo Club, formerly known as the Hammersmith Penguin Swimming Club.[35] Hammersmith Chess Club has been active in the borough since it was formed in 1962. It was initially based in Westcott Lodge, later moving to St Paul's Church, then to Blythe House and now Lytton Hall, near West Kensington tube station.[36]

Transport

The area is on the main A4 trunk road heading west from central London towards the M4 motorway and Heathrow Airport. The A4, a busy commuter route, passes over the area's main road junction, Hammersmith Gyratory System, on a long viaduct, the Hammersmith Flyover.[37] Hammersmith Bridge, the first suspension bridge over the River Thames, allows pedestrians and cyclists to cross to and from Barnes and southwest London, and previously allowed vehicular traffic but has been closed to vehicles since April 2019 for safety reasons.[38]

The centre of Hammersmith is served by two London Underground stations named Hammersmith: one is served by the Hammersmith & City and Circle lines and the other is served by the Piccadilly and District lines. The latter station is part of a larger office, retail and transport development, locally known as "The Broadway Centre". Hammersmith Broadway stretches from the junction of Queen Caroline Street and King Street in the west to the junction of Hammersmith Road and Butterwick in the east. It forms the north side of the gyratory system also known as Hammersmith Roundabout. The Broadway Shopping Centre includes a major bus station. The length of King Street places the westernmost shops and offices closest to Ravenscourt Park Underground station on the District line, one stop west of Hammersmith itself.

In literature and music

Hammersmith features in Charles Dickens' Great Expectations as the home of the Pocket family. Pip resides with the Pockets in their house by the river and goes boating on the river.[39] William Morris's utopian novel News from Nowhere (1890) describes a journey up the river from Hammersmith towards Oxford.[40]

In 1930, Gustav Holst composed Hammersmith, a work for military band (later rewritten for orchestra), reflecting his impressions of the area, having lived across the river in Barnes for nearly forty years.[41] It begins with a haunting musical depiction of the River Thames flowing underneath Hammersmith Bridge. Holst taught music at St Paul's Girls' School and composed many of his most famous works there, including his The Planets suite. A music room in the school is named after him.[42] Holst dedicates Hammersmith: To the Author of "The Water Gypsies." [43]

Notable people

17th century

- John Milton (1608–1674), poet[44]

- William Sheridan (c. 1635 – 3 October 1711), Bishop of Kilmore and Ardagh[45]

18th century

- William Belsham (1752–1827), political writer and historian[45]

- Charles Burney (1757–1817), schoolmaster[45]

- Caroline of Brunswick (1768–1821), princess and Queen Consort of George IV[46]

- William Crathern (born 1793), composer[47]

- Lewis Kennedy (c. 1721–1782), nurseryman[48]

- James Lee (1715–1795), nurseryman[48][49]

19th century

- T. J. Cobden Sanderson (1840–1922), artist and bookbinder[50]

- William Tierney Clark (1783–1852), civil engineer, designer of first Hammersmith bridge[51]

- Gustav Holst (1874–1934), composer, taught music at St Paul's Girls' School[42]

- Leigh Hunt (1784–1859), critic, essayist, poet, and writer[45]

- Edward Johnston (1872–1944), scholar, credited with the revival of calligraphy[52]

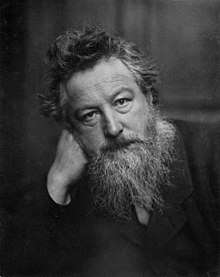

- William Morris (1834–1896), artist, writer, socialist and activist[52]

- Francis Ronalds (1788–1873), inventor, built the first working telegraph at Hammersmith Mall[53]

- Frederic George Stephens (1827–1907), art critic[52]

- Emery Walker (1851–1933), engraver and printer[52]

- George Wimpey (1855–1913), stonemason[54]

- Sir Frank Brangwyn, artist, painter, and designer, lived at Temple Lodge.[55]

- Jeanne Deroin (1805 - 1894), French socialist feminist.

20th century

- Alfie Allen (born 1986), actor[56]

- Lily Allen (born 1985), pop singer[57]

- Bill Bailey (born 1964), comedian[58]

- Sacha Baron Cohen (born 1971), comedian and actor[59]

- Marcus Bent (born 1978), footballer[60]

- Joe Calzaghe (born 1972), boxer[61]

- Sebastian Coe (born 1956), athlete and politician[62]

- Marie Colvin (1956–2012), journalist[63]

- Benedict Cumberbatch (born 1976), actor[64]

- James DeGale (born 1986), boxer[65]

- Cara Delevingne (born 1992), model and actor[66]*

- George Devine (1910–1966), director[67]

- Mary Fedden (1915–2012), artist[68]

- Ralph Fiennes (born 1962), actor[58]

- Emilia Fox (born 1974), actor[69]

- Rosalind Franklin (1920–1958), X-ray crystallographer[70][71]

- Hugh Grant (born 1960), actor[72]

- Michael Gove (born 1967), politician[73]

- George Groves (born 1988), boxer[74]

- Tom Hardy (born 1977), actor[75]

- Miranda Hart (born 1972), actor[76]

- A. P. Herbert (1890–1971), humorist[77]

- Jocelyn Herbert (1917–2003), stage designer[78]

- Edward Elizabeth "Eddie" Hitler, fictional character portrayed by British actor, comedian and musician Adrian Edmondson in the BBC sitcom Bottom.

- Sophie Hunter (born 1978), theatre and opera director[79]

- James May (born 1963), television presenter[80]

- Helen Mirren (born 1945), actor[81]

- Maurice Murphy (1935–2010), trumpet player[82]

- Douglas Murray (born 1979), author, journalist[83]

- Eric Newby (1919–2006), travel writer[84]

- Gary Numan (born 1958), musician [85]

- Scott Overall (born 1983), marathon runner[86]

- Stuart Pearce (born 1962), footballer[87]

- Rosamund Pike (born 1979), actor[88]

- Stephen Poliakoff (born 1952), playwright[89]

- Imogen Poots (born 1989), actor[90]

- Eric Ravilious (1903–1942), artist[91][92]

- Richard Richard, fictional character portrayed by British actor and comedian Rik Mayall in the BBC sitcom Bottom.

- Tony Richardson (1928–1991), theatre and film director[93]

- Alan Rickman (1946–2016), actor[94]

- Diana Rigg (born 1938), actress[95]

- Vidal Sassoon (1928–2012), hairdresser[96]

- Labi Siffre (born 1945), musician[97]

- Luke Stoughton (born 1977), cricketer[98]

- Estelle Swaray (born 1980), musician[99]

- Julian Trevelyan (1910–1988), artist[100]

- Suki Waterhouse (born 1992), actress and model [101]

- Evelyn Whitaker (died 1929), children's writer[102]

- Alan Wilder (born 1959), rock musician[103]

- Richard Ayoade (born 1977), actor and comedian[104]

The poet John Milton lived in Hammersmith.

The poet John Milton lived in Hammersmith. The Arts and Crafts designer William Morris lived on Hammersmith Mall.

The Arts and Crafts designer William Morris lived on Hammersmith Mall. The composer Gustav Holst taught at St Paul's Girls School.

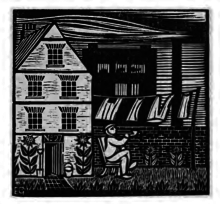

The composer Gustav Holst taught at St Paul's Girls School. The artist Eric Ravilious lived in Hammersmith and made this 1928 painting, representing himself as the small central figure.

The artist Eric Ravilious lived in Hammersmith and made this 1928 painting, representing himself as the small central figure. The actor Hugh Grant went to Latymer Upper School.

The actor Hugh Grant went to Latymer Upper School.

See also

- List of districts in Hammersmith and Fulham

References

- Mills, A. D. (1993). A Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0192831313.

- "Hammersmith". GENUKI. Description and Travel: GENUKI Charitable Trust. 2 January 2017. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018.

- Staff (1902). "Hammersmith". Royal Thames Guide. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Company. pp. 9–11, page 11. OCLC 47982768.

- The bust is a 1665 bronze copy of the marble bust made by LeSueur in 1631. "Image of bronze bust of Charles I, Hammersmith". Archived from the original on 24 May 2013., "Search Hammersmith Historical Sculptures: Charles I by Le Sueur". Archived from the original on 24 May 2013.

- "Bombs, bearings and barges - a brief history of Hammersmith Bridge". London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham Council. 18 September 2012. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013.

- "Hammersmith Bridge super sewer threat". London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham Council. 18 September 2012. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012.

- "History of Olympia". London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham Council. 20 August 2010. Archived from the original on 11 September 2010.

- Willson, Eleanor Joan (1961). James Lee and the Vineyard Nursery, Hammersmith. London: Hammersmith Local History Group.

- CEGB Statistical Yearbook 1965, CEGB, London.

- "HUC History". Hammersmith United Charities. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- "Charing Cross Hospital". NHS. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Savills UK | 404". Savills.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- "Hammersmith Bridge Road Surgery London by Guy Greenfield". Galinsky.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- Dan Hodges. "Best and worst of Hammersmith and Fulham buildings named". Archived from the original on 10 August 2011.

- "architectureweek.org.uk". architectureweek.org.uk. 24 June 2007. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- Historic England. "The Black Lion public house (1192979)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- Historic England. "The Dove Inn public house (1079783)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Historic England. "The George public house (1358573)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- Historic England. "Hop Poles public house (1079826)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Historic England. "Hope and Anchor Public House (1392791)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Historic England. "Salutation Inn (1079763)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Historic England. "The Swan public house (1192058)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- Historic England. "St Paul's, Hammersmith (1079802)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- Historic England. "Church of St Peter (1079843)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "Riverside Studios". Theatres Trust. 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Website Archived 21 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine of the Standing Conference of Polish Museums, Archives and Libraries

- Benedict Le Vay, Eccentric London

- "UnToldLondon". UnToldLondon. 19 January 2012. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- Kirby, Terry (11 February 2006). "750,000 and rising: how Polish workers have built a home in Britain". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- "posk.org". posk.org. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- "About". The Dove, Hammersmith. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Cole, Melissa (17 August 2008). "Beer Girl". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- "London Gardens Online". londongardensonline.org.uk. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- "Time Out, "London's best local parks," 29 August 2008". Timeout.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- "Penguin Swimming Club Of Hammersmith Pictures and Images". Getty Images. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- "A Brief History of Hammersmith Chess Club". Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- Rawlinson, S. R. J.; Stott, P. F. (1962). "The Hammersmith Flyover". ICE Proceedings. 23 (4): 565. doi:10.1680/iicep.1962.10813.

- Historic England. "Hammersmith Bridge (1079819)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Calvert, Laurie. "A Teacher's Guide to the Signet Classics Edition of Charles Dickens's Great Expectations" (PDF). Penguin Books. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Creating a utopian future: William Morris's News from Nowhere". The British Library. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "The Music of Gustav Holst (1930) Hammersmith Op. 52". GustavHolst.info. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Warrack, John (January 2011). "Holst, Gustav Theodore". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 4 April 2013. (subscription required)

- Holst, Gustav. Hammersmith, Op. 52 (Musical Score) (Corrected Edition 1986 ed.). London: Boosey & Hawkes. p. 1.

- Lewalski, Barbara K. The Life of John Milton. Oxford: Blackwells, 2003.

- "Hammersmith | British History Online". British-history.ac.uk. 1 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Queen Caroline of Brunswick, wife of George IV". Historic–uk.com. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Carl Czerny (2011). Voluntaries for organ. A–R Editions. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-89579-709-4. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Botanists: the Gardeners and the Nurserymen". Quakers in the World. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Ray Desmond (25 February 1994). Dictionary Of British And Irish Botantists And Horticulturalists Including plant collectors, flower painters and garden designers. CRC Press. p. 421. ISBN 978-0-85066-843-8. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "One man's obsession with rediscovering a lost typeface". BBC News. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "William Tierney Clark". London Remembers. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016.

- "The House & Interiors | Emery Walker and 7 Hammersmith Terrace". Emerywalker.org.uk. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- Adrian Room (1992). Corporate eponymy: a biographical dictionary of the persons behind the names of major American, British, European, and Asian businesses. McFarland. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-89950-679-1. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/frank-brangwyn/

- "Alfie Allen - Stars On Stage". London Theatre. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- Culbertson, Alix (20 January 2015). "Hammersmith's Lily Allen and Rik Mayall most explicit UK singers". Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Living with the stars". Telegraph. 8 September 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Irvine, Chris (9 December 2010). "The career of Sacha Baron Cohen". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Swales, Andy. "Marcus Bent handed 12–month suspended prison sentence | Football News". Sky Sports. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Levy, Glen (6 February 2009). "Joe Calzaghe – TIME". Content.time.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Lord Coe: timeline of an Olympic champion and sports administrator". Telegraph. 19 August 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Brenner, Marie. "Marie Colvin's Private War". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Phoebe Luckhurst (15 December 2014). "English charmers: the similarities between Benedict Cumberbatch and Eddie Redmayne | London Life | Lifestyle". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Anderson, David (14 May 2015). "James DeGale backing himself to 'make history' in Andre Dirrell world title fight". The Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 29 November 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Person Details for Cara Jocelyn Delevingne, "England and Wales Birth Registration Index, 1837-2008"". FamilySearch.org.

- John Osborne (30 October 2014). Damn You England: Collected Prose. Faber & Faber. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-571-31836-0. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Phillippa Bennett (2010). William Morris in the Twenty–first Century. Peter Lang. p. 30. ISBN 978-3-0343-0106-0. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Emilia Fox: A long line of theatrical Emila used to be a childminder in her spare time before taking up acting ancestors..." TheGenealogist. 20 September 2011. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- Berger, Doreen (3 December 2014). "A Biography of The Dark Lady Of Notting Hill". United Synagogue Women. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- Sayre, A. (1975). Rosalind Franklin and DNA. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-07493-5.

- Pukas, Anna (1 February 2014). "Why does Hugh Grant refuse to grow up?". The Daily Express. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Londoner's Diary: Finally, Michael Gove flees the Notting Hill set". Evening Standard. 24 March 2017.

- Flanagan, Aaron (30 January 2016). "What channel is George Groves vs Andrea Di Luisa on?". The Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Grainger, Lisa (18 April 2013). "Tom Hardy's Travelling Life". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- "Miranda Hart on how her Falklands hero dad's ship was bombed". The Daily Mirror. 26 January 2012. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Andrew Duncan (2008). Walking London: Thirty Original Walks in and Around London. New Holland Publishers. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-84773-054-1. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Timothy O'Brien. "Obituary: Jocelyn Herbert | Global". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- O'Neill, Lorena. "Meet Sophie Hunter, Benedict Cumberbatch's Impressive Fiancee". The Hollywood Reporter.

- "Transmission – BBC Top Gear Video: behind-the-scenes at the first of the new series «". Transmission.blogs.topgear.com. 23 January 2011. Archived from the original on 3 December 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- Curtis, Nick (19 November 2013). "Helen Mirren: When Peter Morgan sent me The Audience script I emailed him 'you bastard'". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- Barry Millington. "Maurice Murphy obituary | Music". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Law, Katie (4 May 2017). "Douglas Murray on immigration, Islam and identity". The Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017.

- Nicholas Wroe, "Around the world in 80 ways" Archived 30 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 9 June 2001.

- "Gary Numan documentary to get SXSW world premiere".

- "London 2012 Meet Team GB Scott Overall". The Times. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Stuart Pearce". England Football Online. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Cavendish, Lucy (18 March 2009). "Rosamund Pike interview". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- "Hammersmith's Local Community Web Site". Hammersmithtoday.co.uk. 51.490405 –0.232193. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2016.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Shields, Rachel (2 May 2010). "Imogen Poots: A bright young thing who won't suffer for her art". The Independent. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Eric Ravilious blue plaque in London". Blue Plaque Places. Blue Plaque Places. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- John Osborne (30 October 2014). Damn You England: Collected Prose. Faber & Faber. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-571-31836-0. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Ealing–born actor Alan Rickman". GetWestLondon. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Miller, Compton. "Living next to a celeb?". standard.co.uk. Evening Standard / ESI Media. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- 6:08PM BST 10 May 2012 (10 May 2012). "Vidal Sassoon". Telegraph. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- http://bandonthewall.org/artists/labi–siffre/%5B%5D

- "Player profile: Luke Stoughton". CricketArchive. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Raphael, Amy (20 January 2012). "Hammersmith homegirl Estelle back for more global glory". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Mervyn Cooke; Philip Reed (8 July 1993). Benjamin Britten: Billy Budd. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-521-38750-7. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Edmonds, Lizzie. "Suki Waterhouse: 'I shouldn't care but I get upset when people send me negative tweets'". Evening Standard.

- "Biography: Evelyn Whitaker, 1844–1929". Evelynwhitakerlibrary.org. 18 July 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Larkin, Colin (27 May 2011). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Omnibus Press. p. 2006. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1547964/

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Hammersmith. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hammersmith, London. |

- London Borough of Hammersmith & Fulham

- Hammersmith's local community web site

- Description of Hammersmith in 1868

- Hammersmith, Fulham and Putney, by Geraldine Edith Mitton and John Cunningham Geikie, 1903, from Project Gutenberg

- NHS Hammersmith and Fulham

- HammersmithLondon Business Improvement District (BID)