Basingstoke

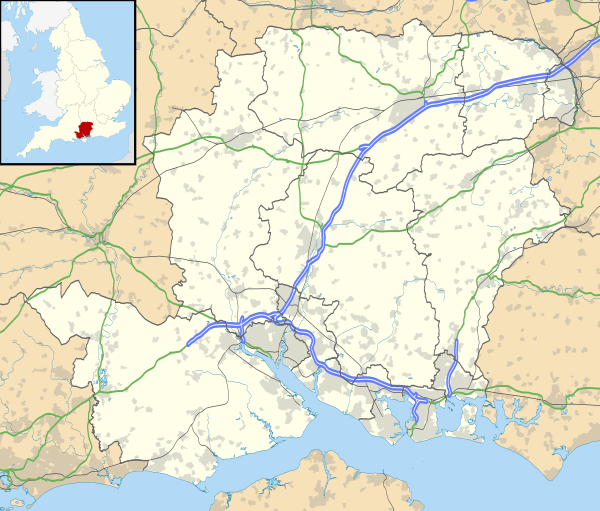

Basingstoke (/ˈbeɪzɪŋstoʊk/ BAY-zing-stohk) is the largest town in the administrative county of Hampshire (Southampton and Portsmouth are now unitary authorities in their own right, and Winchester is a city). It is situated in south central England, and lies across a valley at the source of the River Loddon. It is located 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Southampton, 48 miles (77 km) southwest of London, and 19 miles (31 km) northeast of the county town and former capital Winchester. According to the 2016 population estimate the town had a population of 113,776.[d] It is part of the borough of Basingstoke and Deane and part of the parliamentary constituency of Basingstoke. Basingstoke is often nicknamed "Doughnut City" or "Roundabout City" because of the number of large roundabouts.

| Basingstoke | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

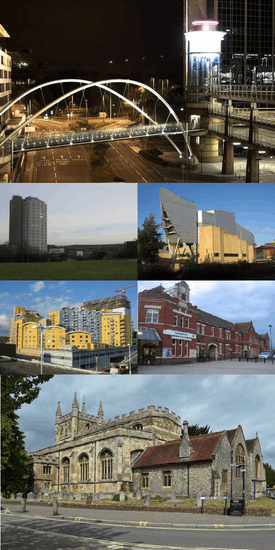

Clockwise from top: Town centre viewed from Churchill Way at night, The Anvil theatre, Basingstoke railway station, St Michael's Church, high-rise flats in Churchill Plaza, and the AA Building (Fanum House) | |

Basingstoke Location within Hampshire | |

| Population | 113,776 [1][a] |

| OS grid reference | SU637523 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Basingstoke |

| Postcode district | RG21–RG24 |

| Dialling code | 01256 |

| Police | Hampshire |

| Fire | Hampshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | www |

Basingstoke is an old market town expanded in the mid 1960s as a result of an agreement between London County Council and Hampshire County Council. It was developed rapidly after World War II, along with various other towns in the United Kingdom, in order to accommodate part of the London 'overspill' as perceived under the Greater London Plan in 1944.[2] Basingstoke market was mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, and it remained a small market town until the early 1960s. At the start of World War II the population was little more than 13,000. It still has a regular market, but is now larger than Hampshire County Council's definition of a market town.[3]

Basingstoke has become an important economic centre during the second half of the 20th century, and houses the locations of the UK headquarters of De La Rue, Sun Life Financial, The Automobile Association, ST Ericsson, GAME, Motorola, Barracuda Networks, Eli Lilly and Company, FCB Halesway part of FCB, BNP Paribas Leasing Solutions, the leasing arm of BNP Paribas in the UK, and Sony Professional Solutions. It is also the location of the European headquarters of the TaylorMade-Adidas Golf Company. Other industries include IT, telecommunications, insurance and electronics.

Etymology

The name Basingstoke (A.D 990; Embasinga stocæ,[4] Domesday; Basingestoches) is believed to have been derived from the town's position as the outlying, western settlement of Basa's people.[5][b] The ending -stoke means outlying settlement or possibly refers to a stockade that surrounded the settlement in early medieval times (of which there is now no trace). Basing, now Old Basing, a village 2 miles (3 km) to the east, is thought to have the same etymology, and was the original Anglo-Saxon settlement of the people led by a tribal chief called "Basa". It remained the main settlement until changes in the local church moved the religious base from St Marys Church, Basing, to the church in Basingstoke.[6][7]

History

Early settlements

A Neolithic campsite of around 3000 BC beside a spring on the west of the town is the earliest known human settlement here, but the Willis Museum has flint implements and axes from nearby fields that date back to Palæolithic times. The hillfort at Winklebury (2 miles (3 km) west of the town centre), known locally as Winklebury Camp or Winklebury Ring[8] dates from the Iron Age and there are remains of several other earthworks around Basingstoke, including a long barrow near Down Grange. The site of Winklebury camp was home to Fort Hill Community School this School is now closed.[9] Nearby, to the west, Roman Road marks the course of a Roman road that ran from Winchester to Silchester. Further to the east, another Roman road ran from Chichester through the outlying villages of Upton Grey and Mapledurwell. The Harrow Way is an Iron-age ancient route that runs to the south of the town. The first recorded historical event here was the victory gained by Æthelred of Wessex and Alfred the Great over the Danes in 871. Again, in 904, Basingstoke saw a savage battle between Edward the Elder, Alfred's only son, and his cousin Æthelwald.

Market town

Basingstoke is recorded as a weekly market site in the Domesday Book, in 1086, and has held a regular Wednesday market since 1214.[10] During the Civil War, and the siege of Basing House between 1643 and 1645, the town played host to large numbers of Parliamentarians. During this time, St. Michael's Church was damaged whilst being used as an explosive store[11] and lead was stripped from the roof of the Chapel of the Holy Ghost, Basingstoke[12] leading to its eventual ruin. It had been incorporated in 1524, but was effectively out of use after the Civil War. The 17th century saw serious damage to much of the town and its churches, because of the great fires of 1601 and 1656. Cromwell is thought to have stayed here towards the end of the siege of Basing House, and wrote a letter to the Speaker of the House of Commons addressed from Basingstoke.[13]

The cloth industry appears to have been important in the development of the town until the 17th century along with malting.[14] Brewing became important during the 18th and 19th centuries, and the oldest and most successful brewery was May's Brewery, established by Thomas and William May in 1750 in Brook Street.[15][16]

Victorian history

The London and South Western Railway arrived in 1839 from London, and within a year it was extended to Winchester and Southampton. In 1848 a rival company, sponsored by the Great Western Railway built a branch from Reading. In 1854 a line was built to Salisbury by the London and South Western.[17] In the 19th century Basingstoke began to move into industrial manufacture, Wallis and Haslam (later Wallis & Steevens), began producing agricultural equipment including threshing machines in the 1850s, moving into the production of stationary steam engines in the 1860s and then traction engines in the 1870s.[18]

Two traders who opened their first shops within a year of each other in the town, went on to become household names nationally: Thomas Burberry in 1856 and Alfred Milward in 1857.[19] Burberry became famous after he invented Gabardine and Milward founded the Milwards chain of shoe shops, which could be found on almost every high street until the 1980s.[20]

Ordinary citizens were said to be shocked[21] by the emotive, evangelical tactics of the Salvation Army when they arrived in the town in 1880, but the reaction from those employed by the breweries or within the licensed trade quickly grew more openly hostile. Violent clashes became a regular occurrence[c] culminating on Sunday 27 March 1881 with troops being called upon to break up the conflict after the Mayor had read the Riot Act. The riot and its causes led to questions in Parliament and a period of notoriety for the town.[22] The town was described as 'Barbarous Basingstoke' by one London newspaper in 1882.[23]

In 1898 John Isaac Thornycroft began production of steam-powered lorries in the town and Thornycroft's quickly grew to become the town's largest employer.[24]

Recent history

Basingstoke was fortunate during the Second World War to suffer very little bomb damage. A stick of German bombs did fall in the Church Square area on 16 August 1940. The same day bombs destroyed part of a row of houses in Burgess Road. Six people were killed in the raid.[25] After the war, the town had a population of 25,000.[26]

As part of the London Overspill plan, along with places such as Ashford and Swindon, Basingstoke was rapidly developed in the late 1960s as an 'expanded town', in similar fashion to Milton Keynes. As the population increased, the town produced more figures of national importance, such as the art critic Waldemar Januszczak and the actress Elizabeth Hurley. Many office blocks and large estates were built, including a ring road.[26] The shopping centre was built in phases. The first phase was completed by the 1970s and was later covered in the 1980s, and was known as The Walks. The second phase was completed by the early 1980s, and became The Malls. The third phase was abandoned and the site was later used to build the Anvil concert hall.[27] The central part of the shopping centre was rebuilt in 2002 and reopened as Festival Place. This has brought a dramatic improvement to shoppers' opinions of the town centre, but it is unclear if it has softened the town's overall image.[26][28]

Geography

Situated in a valley through the Hampshire Downs at an average elevation of 88 metres (289 ft)[29] Basingstoke is a major interchange between Reading, Newbury, Andover, Winchester, and Alton, and lies on the natural trade route between the southwest of England and London. The area had been something of an interchange even in ancient times. It had been cut by a Roman roadway that ran from northeast to southwest, from Silchester towards Salisbury (Sorbiodunum), and by another Roman road that linked Silchester (Calleva Atrebatum) in the north with Winchester (Venta Belgarum) to the south. These cross-cutting highways, along with the good agricultural land hereabouts, account for the many “Roman” villas in the area, mostly put up by Romanized native nobility (Roman villa). Even more ancient was the Harrow Way, a Neolithic trackway, possibly associated with the ancient tin trade, that crossed all of southern England from west to east, from Cornwall to Kent, passing right through Andover and Basingstoke.

Physical geography and geology

The precise size and shape of Basingstoke today are difficult to identify, as it has no single official boundary that encompasses all the areas contiguous to its development. The unparished area of the town represents its bulk, but several areas that might be considered part of the town are separate parishes, namely Chineham, Rooksdown, and Lychpit. The unparished area includes Worting which was previously a separate village and parish,[30] extending beyond Roman Road and Old Kempshott Lane, which might otherwise be considered the town's 'natural' western extremity.

Relying on the M3 as the southern boundary, Roman Road as the western, and considering Chineham as the "tail" to the north-east, Basingstoke can best be described as "kite-shaped" with the tip pointing towards the south-west and this can be clearly seen on an aerial photograph of the town and its environs.

Basingstoke is situated on a bed of cretaceous upper chalk with small areas of clayey and loamy soil, inset with combined clay and flint patches. Loam and alluvium recent and pleistocene sediments line the bed of the river Loddon. A narrow line of tertiary Reading beds run diagonally from the northwest to the southeast along a line from Sherborne St John through Popley, Daneshill and the north part of Basing. To the north of this line, encompassing the areas of Chineham and Pyotts Hill, is London clay, which has in the past allowed excavation for high quality brick and tile manufacture.[31]

Divisions and suburbs

Basingstoke's expansion has absorbed much surrounding farmland and scattered housing, transforming it into housing estates or local districts. Many of these new estates are designed as almost self-contained communities, such as Lychpit, Chineham, Popley, Winklebury, Oakridge, Kempshott, Brighton Hill, Viables, South Ham, Black Dam, Buckskin and South Ham Extension and Hatch Warren. The M3 acts as a buffer zone to the south of the town, and the South Western Main Line constrains the western expansion, with a green belt to the north and north-east, making Basingstoke shaped almost like a kite. As a result, the villages of Cliddesden, Dummer, Sherborne St John and Oakley, although being very close to the town limits, are considered distinct entities. Popley, Hatch Warren and Beggarwood are seeing rapid growth in housing.[32][33]

Demography

The population has increased from around 2,500 in 1801 to over 52,000 in 1971; the most significant growth occurring during the latter half of the 20th century.[34] The borough of Basingstoke was merged with other local districts in 1974 to form the borough of Basingstoke and Deane. Since then most census data has been for the larger area: before 1974, census information was published for the town as a separate entity.

Figures published for the most recent UK census in 2011 for the Borough of Basingstoke and Deane, give a population of 167,799 and a population density of 2.7 persons per hectare—only about half the national figure.[35] The number of women slightly exceeded that of men, and a slight increase in the percentage of residents over 65 was also noted.[36] The present century has seen rapid social change in the town: whereas 96.6 per cent of the population were classified as White British in 2001, this number had declined to 88.3 per cent by 2011. Now 4.3 per cent had originated elsewhere in Europe, and a further 3.4 per cent were of Asian origin. Similarly, with regard to religion, there was a big change: those declaring themselves as Christian declined in ten years from 74 per cent to 60 per cent. This was not because of a big influx of adherents to other faiths, but rather because those who held to no religion increased to 30 per cent of the population by 2011. Among other findings in 2001 were that 74.33 per cent felt they were in good health, 50.98 per cent were economically active full-time employees (over 10 per cent higher than the national average) and 48.73 per cent were buying their property with a mortgage or loan (almost 10 per cent higher than the national average).[35] Amongst the working population, 64.2 per cent travelled less than 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) to work.[37] The biggest percentage of employees, 17.67 per cent, worked in real estate, renting and business activities.[38]

Governance

Basingstoke is part of a two-tier local government structure and returns county councillors to Hampshire County Council. When the cities of Southampton and Portsmouth attained unitary authority status in 1998, Basingstoke became the largest settlement in the county administered by the county council,[39][40] although it remains the third largest settlement in the ceremonial county.

Basingstoke and Deane is the local Borough Council and has its offices in the town centre. Elections to the council take place in 3 out of every 4 years.

Under the town twinning scheme, the local council have twinned Basingstoke with Alençon in France,[41] Braine-l'Alleud in Belgium, and Euskirchen in Germany.[42]

Facilities

The former Town Hall, adjoining the old marketplace, houses the Willis Museum (originally the Basingstoke Museum, until 1956). This was founded and directed by Alderman George W. Willis, a local clocksmith, who served as Mayor of Basingstoke in 1923-24. He established the museum in 1931 and with much public support was able to build it up into a major collection on local history, with a particularly extensive collection (largely made by him) of prehistoric implements and of antique clocks and watches. His association with the expanding museum continued for forty years. Its central location today is where, once upon a time, Jane Austen and her sister used to go to dances. Although ostensibly set in Hertford, Austen's novel Pride and Prejudice, written in 1797, is thought to have been based on her view of Basingstoke society two centuries ago.

The Top of Town is the historic heart of Basingstoke, housing the Museum[43] in the former Town Hall building (rebuilt 1832) as well as several locally run shops and the market place. Basingstoke is also home to multiple theatrical organisations: The Anvil,[44] and the Haymarket, situated in the former Corn Exchange.

Festival Place, opened in October 2002, gave a huge boost to the town centre whilst transforming the former The Walks Shopping Centre and the New Market Square.[45] Aside from a wide range of shops, there is also a range of cafés and restaurants as well as a large multiscreen Vue cinema (formerly Ster Century from Festival Place's opening until their takeover in 2005; the pre-existing Vue in the Leisure Park was sold to Odeon).[46]

Central Basingstoke has two further shopping areas: The Malls and the Top of Town. The Malls area had declined since the opening of Festival Place and the closure of its Allders department store, though still home to several major retailers. The leasehold was purchased in 2004 by the St Modwen development group in partnership with the Kuwait property investment company Salhia Real Estate, with provision for redevelopment[47] The redevelopment of The Malls started in late 2010, and the shopping centre was given a major facelift. The existing canopies were removed and a clear roof canopy installed, to protect the centre from bad weather, but still allow natural light and air in. The whole shopping centre has been repaved and new street furniture installed. A new gateway entrance to The Malls links it to the rail station. The redevelopment was completed in the last quarter of 2011. The redevelopment work has been carried out by Wates Group using a variety of subcontractors.[48]

In November 2015, as part of the redevelopment of BasingView a co-located John Lewis at home and Waitrose store was opened.

The town's nightlife is split between the new Festival Square, and the traditional hostelries at the Top of Town, with a few local community pubs outside the central area. The town has four nightclubs, two in the town itself, one on the east side and one 2 miles (3.2 km) out to the west.

In Portchester Square is the Basingstoke Sports Centre which has a subterranean swimming pool, sauna, jacuzzi and steam room. Above ground there is a gym, aerobics studios, squash courts and main hall. There is also an Ofsted-registered crèche.[49]

Sports and leisure

Outside the town centre, there is a leisure park featuring the Aquadrome swimming pool, which opened in May 2002.[50] The park includes an ice rink, bowling alley, Indoor sky-diving centre with ski and surf machines, Bingo club and a ten screen Odeon (formerly Vue prior to the takeover of the Ster Century cinema in Festival Place, and before that, Warner-Village) cinema, as well as a restaurant and fast food outlets. The leisure park is home to the Milestones Museum which contains a network of streets and buildings based on the history of Hampshire.

Basingstoke has a football club, Basingstoke Town F.C. the Basingstoke Rugby Football Club, and the Basingstoke Bison ice hockey team. Basingstoke also has a swimming team,[51] known as the Basingstoke Bluefins and an American Flag Football Team known as the Basingstoke Zombie Horde.[52] The diversity of sporting activity in the area is also illustrated by organisations such as Basingstoke Demons Floorball Club, Basingstoke Volleyball Club, Basingstoke Bulls Korfball Club and Lasham Gliding Society. The home ground of Basingstoke & North Hants Cricket Club, Mays Bounty was until 2000 used once a season by Hampshire County Cricket Club.[53][54][55][56] As of 2011, Basingstoke has a roller derby league and team, the Basingstoke Bullets. Due to difficulty finding a suitable venue, the team practice in nearby Whitchurch. Basingstoke is also the home of Rising Phoenix Cheer, a successful competitive Allstar Cheerleading programme for athletes from age 5 upwards, training at Aldworth school.

Plans have recently been announced for a new multimillion-pound sports facility at Down Grange, which would be suitable for many sports. Proposals include a stadium for Basingstoke Town FC and Basingstoke RFC which would be up to the standard of the Football League, a new 8 lane athletics track and hockey pitch, as well as a gym, swimming pool, hotel and conference facilities.

Musical groups

Basingstoke has a wide diversity for musical groups ranging from brass bands to symphony orchestras.[57] The Basingstoke Concert Band is a traditional wind band which has now been in existence for more than 35 years.[57] The band was started by Lawrie Shaw when Brighton Hill Community School opened in Basingstoke in 1975 where he was the first headteacher. Lawrie formed the band as an evening class for amateur wind players and it was then known as the Brighton Hill Centre Band.[58]

Media

Basingstoke is served by regional radio stations The Breeze serving North Hampshire and parts of Surrey and Sussex and Heart Berkshire, broadcast from Reading and London also provides regional coverage in the area. BBC Berkshire is available in the town. The town has coverage from digital radio; the BBC, Independent National and Now Reading multiplexes can be received in the town,[59] and the outskirts can receive London and South Hampshire stations as well.[60][61] The BBC national stations and DAB coverage is enhanced by a small relay just south of the town centre.[62]

Local TV coverage is provided by BBC South and ITV Meridian, with BBC London and ITV London also received in the town. There are two local newspapers – the Basingstoke Gazette, and the Basingstoke Observer. The town is also covered by the broadsheet newspaper Hampshire Chronicle.[62]

Education

The Holy Ghost School (subsequently Queen Mary's School for Boys) was a state funded grammar school operating in Basingstoke for four centuries, from 1556 until 1970, producing nationally recognised alumni such as Revd. Gilbert White (1720-1793), a pioneer naturalist, and the famed cricket commentator, John Arlott (1914-1991).

In modern times education in Basingstoke has been co-ordinated by Hampshire County Council. Each neighbourhood in the town has at least one primary school, while secondary schools are distributed around the town on larger campuses. Basingstoke has two large further education colleges: a sixth form college, Queen Mary's College (QMC) and Basingstoke College of Technology (BCoT). The University of Winchester had a campus in Basingstoke (Chute House Campus) which closed in July 2011; it had offered full-time and part-time university courses in subjects including childhood studies, various management pathways, community development and creative industries. Bournemouth University's health and social care students can work on placement at the North Hampshire Hospital.[63] However, the hospital only caters for midwifery students.[64]

Transport

Basingstoke is at Junction 6 and Junction 7 of the M3 motorway, which skirts the town's southeastern edge, linking the town to London and to Southampton and the south-west. The central area of the town is encircled by a ring road constructed in the 1960s named The Ringway, and is bisected east to west by the A3010 (Churchill Way). The A33 runs north east to Reading and the M4 Motorway, and south west to Winchester.[65] The A30 runs east to Hook and west to Salisbury. The A303 begins a few miles south west of Basingstoke to head west towards Wiltshire and the West Country, sharing the first few miles with the A30. The A339 runs south east to Alton and north west to Newbury. Basingstoke has a reputation for having a large density of roundabouts, and with some larger roundabouts dealing with traffic from six directions, this only adds to the illusion, as does the fact some multilevel junctions on the Ringway were never built or completed.[66]

The South Western Main Line railway runs east and west through the centre of the town and Basingstoke railway station linking it to the West of England Main Line to Salisbury and the South West of England, London Waterloo (the fastest train Basingstoke to London takes 44 minutes), Winchester, Southampton, Bournemouth and Weymouth, and via the Eastleigh to Fareham Line and West Coastway Line to Portsmouth and Brighton. The West of England Main Line to Salisbury and Exeter diverges at Worting Junction, to the west. The Basingstoke Branch[67] runs north-east to Reading, providing services to Oxford, Birmingham, the north of England and Scotland. The town was the terminus of the defunct Basingstoke and Alton Light Railway. Current rail services from Basingstoke are operated by South Western Railway, CrossCountry and Great Western Railway.

Most bus services in the town operate from Basingstoke Bus Station. The majority are provided by the Stagecoach Group through their Stagecoach in Hampshire sub-division.[68] Basingstoke Community Transport and Communities First Wessex run some smaller routes.[69][70] A park and ride shuttle operated by Stagecoach links Basingstoke Leisure Park with Basing View, via Basingstoke Railway Station. This service provides a daytime service at roughly 10-minute intervals throughout the week.[71] A peak time service is provided by Courtney Coaches between Chineham Business Park and the railway station.[72] National Express offers direct coach services to London, Heathrow Airport and Southampton from the bus station.

Separating provision for cyclists from other road traffic was not part of the remit of the 1960s town redevelopment, and in 1996 the perception of provision for cyclists was very poor.[73] A Basingstoke Area Cycling Strategy was developed in 1999[74] and subsequently an extensive cycle network has been developed[75] mainly utilising on-road routes or off-road routes that run parallel with and directly alongside roads. Basingstoke was linked to Reading on the National Cycle Network route 23 in May 2003 and the route was extended south to Alton and Alresford in April 2006.

Basingstoke Canal

The Basingstoke Canal started at a canal basin, roughly where the cinema in Festival Place is located. From there the canal ran alongside the River Loddon following the line of Eastrop Way. The old canal route passes under the perimeter ring road and then follows a long loop partly on an embankment to pass over small streams and water meadows towards Old Basing, where the route goes around the now ruined palace of Basing House and then through and around the eastern edge of Old Basing. It followed another loop to go over small streams near the Hatch public house (a lot of this section was built over when constructing the M3) and headed across fields on an embankment towards Mapledurwell. The section of the canal from Up Nately to the western entrance of the Greywell Tunnel still exists and is a nature reserve; there is water in the canal and the canal towpath can be walked. A permissive footpath at the western entrance to the tunnel allows walkers to access public footpaths to get to the eastern entrance of the tunnel. The limit of navigation is about 500m east of the Greywell Tunnel. The renovated sections of the canal can then be navigated east towards West Byfleet where it joins the Wey Navigation, which itself can be navigated to the River Thames at Weybridge.

Plans to reconnect Basingstoke with the surviving sections of the Canal have been delayed several times in the past and this remains a long term aim of the Surrey and Hampshire Canal Society.[76]

Religious sites

The Anglican church of St. Michael's is west of Festival Place and the chancel dates from 1464;[77] the south chapel may be older.[78] The nave and aisles were added 50 years later by Richard Foxe, Bishop of Winchester. The Memorial Chapel at the north east corner of the church was completed in 1921. The ruined Chapel of the Holy Ghost, north of the railway station, has not been a place of worship for the past four centuries, an effect of the Reformation. It was built by the first Lord Sandys, beginning in 1524, when King Henry VIII issued a charter of incorporation. However the west tower of a 13th-century building survives.[78] It is surrounded by an ancient cemetery; William, Lord Sandys himself lies buried in the chapel with his wife. The Church of St Mary, Eastrop is an old church enlarged in 1912.[79] All Saints' Church was built in 1915, designed by Temple Moore.[79] St Peter's Church was built in 1964-5 designed by Ronald Sims and is in a housing estate built in the 1960s.[80] In 2014 a group named Basingstoke Community Churches covered an area of six churches in the town.[81] There is also an Assemblies of God church called Wessex Christian Fellowship, two very new Roman Catholic churches, St. Bede's and St. Joseph's, and churches of other denominations.[82] In 2019 Gateway Church Basingstoke began a partnership with Christians Against Poverty (CAP) to launch a Debt Centre in Basingstoke.[83]

Cultural associations

"Basingstoke" is a code word in Gilbert and Sullivan's 1887 comic opera Ruddigore, used by the "bad baronet" after he reforms, to remind his bride "Mad Margaret" of their plan to live lives of boring respectability.[84] In 1895, Thomas Hardy referred to Basingstoke as "Stoke Barehills" in Jude the Obscure. The town is mentioned in Agatha Christie's They Do It with Mirrors and is widely thought to be the location of Market Basing in the Miss Marple stories. Patrick Wilde's 1993 play, What's Wrong with Angry? is set in Basingstoke. It was later adapted into the 1998 film, Get Real, which was filmed at various locations around Basingstoke.[85]

Basingstoke's North Hampshire Hospital was one of two hospitals used for the filming of Channel 4's hit comedy Green Wing.[86] George Formby's film, He Snoops to Conquer, was partly shot in the town in 1944. And in 1974 the National Film Board of Canada produced a documentary here called Basingstoke – Runcorn: British New Towns. The former Park Prewett Mental Hospital was the setting for the novel Poison in the Shade (1953), by Eric Benfield, a local author and sculptor who worked as an art therapist at that hospital.

Notable people

Notes

a. ^ Population figure is an estimate for 2010, and includes only the unparished area, not the surrounding area.

b. ^ The List of generic forms in British place names shows a toponymic interpretation of the various Old English elements within the names Basing and Basingstoke. Bas is taken to be from the personal name 'Basa', ingas as 'people of' and stoc as 'dependent farmstead' or 'secondary settlement'.

c. ^ In summarising to Magistrates at the trial of those members of the public said to have rioted against the Salvationists, defence counsel stated that Until this body known as the Salvation Army was formed here, the number of summonses which had come before the Magistrates was comparatively unknown. They now had a large number of assault cases to hear. The army perfectly well knew that their conduct was leading to disturbances in the town. The case against the defendants was dismissed.[87]

d. ^ In 2012 the town itself had a population of 84,275, but this does not include the large suburban villages of Chineham, Old Basing or Lychpit, which are now considered as outer suburbs of the town.

References

- "Hampshire County Council, Small Area Population Forecasts. Parish data: Parish total level forecast: (unparished area) Basingstoke & Deane". Hampshire County Council. 2016. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- Stokes, Eric (1980). Basingstoke – Expanding Town. The Workers' Educational Association. p. 15.

- "Rural Hampshire FAQs". Hampshire County Council. 2006. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2007.

- "Anglo-Saxon Charters". Sean Miller. 2006. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- "English Place Names". The University of Nottingham. 2006. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- "Old Basing & Lychpit Parish History". Old Basing & Lychpit Parish Council. 2006. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- Mills, A.D. (1991). A Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-19-869156-4.

- "A brief history of Winklebury Ring". Fort Hill Community School. 2005. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- "Hampshire Treasures Vol 2". Hampshire County Council. 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- "Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs". Centre for Metropolitan History. 2004. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- "St Michael's Church – the building". Hampshire County Council. 2006. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- "Hampshire Treasures Vol 2". Hampshire County Council. 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- Baigent, Francis J.; James Millard (1889). A History of the Ancient Town and Manor of Basingstoke. C.J. Jacob. p. 565.

- "Victorian County History – Hampshire Vol 4". British History Online. 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- Worker's Educational association; Willis, George (1972). "10". In Barbara McKenzie (ed.). Historical Miscellany of Basingstoke. Basingstoke: The Crosby Press. p. 53.

- Hawker, Anne (1984). "7". The Story of Basingstoke. Newbury: Local Heritage Books. p. 68. ISBN 0863680119.

- Christopher J. Tolley (2001). "Basingstoke's Railway History in Maps". Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "Wallis and Steevens – A Timeline". Hampshire County Council. 2006. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- Hawker, Anne (1999). The Story of Basingstoke. Hampshire County Museum Service. p. 69.

- "Milward's celebrates 125 years of footwear". Hants & Berks Gazette. 1982.

- Baigent, Francis J.; James Millard (1889). A History of the Ancient Town and Manor of Basingstoke. C.J. Jacob. p. 552.

- Baigent, Francis J.; James Millard (1889). A History of the Ancient Town and Manor of Basingstoke. C.J. Jacob. pp. 551–553.

- Bob Clarke (2010) The Basingstoke Riots (ISBN 978-0-9508095-6-4)

- "Thornycroft of Basingstoke". Hampshire County Council. 2005. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- Attwood, Arthur. Basingstoke: Arthur Attwood's look into the past. Basingstoke: Basingstoke gazette. pp. 57–60.

- "A Brief History - Basingstoke census". Basingstoke.gov. Basingstoke and Deane. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- "History of The Anvil". Anvil Arts. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- "Central Basingstoke Vision, Single Issue Panel Meeting No 5". Basingstoke & Deane Borough Council. 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2007.

- "Meteoconsult web site". Unitedkingdom.meteoconsult.co.uk. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- "Victoria County History, Worting Parish". British History Online. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- Stokes, Eric (1980). Basingstoke – Expanding Town. The Worker's Educational Association. p. 45.

- "Report of the Director of Property, Business and Regulatory Services". Hampshire County Council. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- "Report of the Director of Environment". Hampshire County Council. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- "A Vision of Britain Through Time". Great Britain Historical GIS Project. 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- "Neighbourhood Statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- "Neighbourhood Statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- "Neighbourhood Statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- "Neighbourhood Statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- "Hampshire County Council library service, Best Value Inspection 2001" (PDF). Hampshire County Council. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- "Combined feasibility and building design project appraisal". Hampshire County Council. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- "Twin Towns in Hampshire". Hampshire County Council. Archived from the original on 30 November 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- "Willis Museum". Hampshire County Council. Archived from the original on 18 August 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- "The Anvil". Anvil Arts. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- "The Place to be proud of!". Thisishampshire.net. 2004. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- "Completed acquisition by Vue Entertainment Holdings". Office of Fair Trading. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- "St Modwen buys Basingstoke's Malls with Key Kuwaiti partner". Property Week.com. 2004. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- "The Malls Transformation". Basingstoke.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- "Sports Centre". Basingstoke & District Sports Trust Limited. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- "Aquadrome opens its shores to swimmers". This is Hampshire.net. Archived from the original on 26 January 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- "Basingstoke Bluefins". Swimblue. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "Basingstoke Zombie Horde". Rollhorde. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "Hampshire v Yorkshire, CGU National League, May's Bounty, Basingstoke 13 June 1999". cricket-online.org. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- "Hampshire v Yorkshire, County Championship, May's Bounty, Basingstoke 2–4 June 1992". cricket-online.org. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- "Hampshire v Durham, County Championship, May's Bounty, Basingstoke 14–16 June 2000". ESPNcricinfo. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- Arlott, John (1990). Basingstoke Boy. Willow Books, Harper Collins. p. 26.

- "Artistic Associates, The Anvil". Anvil Arts. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- "Basingstoke Concert Band". Bcband. Basingstoke Concert Band. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- "DAB Digital Radio Coverage Maps". MDS975.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 September 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- "Digital Radio Now, Station Finder". digitalradionow.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- "Radio stations in the South Midlands and Thames Valley". radio-now.co.uk. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- "Basingstoke Relay Station". MB21.

- "Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospital Healthcare Library". Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- "Contacts & Rents for Hospital Accommodation". Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- "Popham Airfield home page". Chris Thompson, Popham Airfield. 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- "Brimpton Airfield". Brimpton Flying Club. 2007. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- Crawford, Ewan (2002). "Basingstoke Branch". Ewan Crawford. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- "Stagecoach Basingstoke network map" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- Basingstoke Community Transport

- Dial A Ride Basingstoke

- Centre Shuttle

- "Corporate Contracts". 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Public attitudes on Transport Issues". Hampshire County Council. 1996. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- "Basingstoke Environmental Strategy for Transport". Hampshire County Council. 2000. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- "Basingstoke Cycle Network Map" (PDF). Hampshire County Council. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- "Basingstoke Canal – The last 5 miles". Surrey and Hampshire Canal Society. 2004. Archived from the original on 17 June 2007. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- "St Michael's Church, Basingstoke". 14 January 2009. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1967). Buildings of Hampshire. london: Penguin. p. 90.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1967). Buildings of Hampshire. London: Penguin. p. 91.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1967). Buildings of Hampshire. London: Penguin. p. 93.

- "Our Churches". Basingstoke Community Churches. BCC. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "Wessex Christian Fellowship".

- http://www.gatewaylife.co.uk/care/

- One writer stated that Gilbert's reference was inspired by an incident, the year before Ruddigore premiered, where the governing party spent much of a summer in a manor near a Basingstoke mental hospital to avoid both the stench of a recent sewer blockage in London and the anger of the people with whom they were unpopular.Bosdêt, Mary (November–December 1992). "Whence Basingstoke!?". GASBAG. XXIV (185): 7. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- Shaw, Pete (2007). "Get Real, Basingstoke filming locations". bensilverstone.net. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- Raphael, Amy (29 March 2006). "Green Wing's midwife and surgeon". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 26 December 2006.

- The Salvation Army at Basingstoke. Report of the proceedings before the Magistrates on May 3rd and 9th, 1881. Basingstoke. 1881.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Basingstoke. |

- Official website

- Local info on Basingstoke from Hampshire County Council

- Basingstoke in the Domesday Book

- Further historical information and sources on GENUKI