Oxford Street

Oxford Street is a major road in the City of Westminster in the West End of London, running from Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch via Oxford Circus. It is Europe's busiest shopping street, with around half a million daily visitors, and as of 2012 had approximately 300 shops. It is designated as part of the A40, a major road between London and Fishguard, though it is not signed as such, and traffic is regularly restricted to buses and taxis.

.jpg) View east along Oxford Street in May 2016 | |

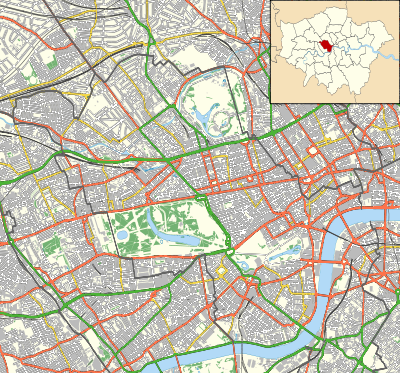

Location within Central London | |

| Former name(s) | Via TrinobantinaTyburn Road |

| Maintained by | Transport for London |

| Length | 1.2 mi (1.9 km) |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Postal code | W1 |

| Nearest Tube station |

|

| Coordinates | 51.515312°N 0.142025°W |

| West end | Marble Arch |

| East end | Tottenham Court Road / Charing Cross Road |

| Other | |

| Known for | |

| Website | oxfordstreet |

The road was originally part of the Via Trinobantina, a Roman road between Essex and Hampshire via London. It was known as Tyburn Road through the Middle Ages when it was notorious for public hangings of prisoners at Tyburn Gallows. It became known as Oxford Road and then Oxford Street in the 18th century, and began to change from residential to commercial and retail use by the late 19th century, attracting street traders, confidence tricksters and prostitution. The first department stores in the UK opened in the early 20th century, including Selfridges, John Lewis & Partners and HMV. Unlike nearby shopping streets such as Bond Street, it has retained an element of downmarket trading alongside more prestigious retail stores. The street suffered heavy bombing during World War II, and several longstanding stores including John Lewis were completely destroyed and rebuilt from scratch.

Despite competition from other shopping centres such as Westfield Stratford City and the Brent Cross Shopping Centre, Oxford Street remains in high demand as a retail location, with several chains having their flagship stores on the street, and has a number of listed buildings. The annual switching on of Christmas lights by a celebrity has been a popular event since 1959. As a popular retail area and main thoroughfare for London buses and taxis, Oxford Street has suffered from traffic congestion, pedestrian congestion, a poor safety record and pollution. Various traffic management schemes have been implemented by Transport for London (TfL), including a ban on private vehicles during daytime hours on weekdays and Saturdays, and improved pedestrian crossings.

Location

Oxford Street runs for approximately 1.2 miles (1.9 km). It is entirely within the City of Westminster.[1] The road begins at St Giles Circus as a westward continuation of New Oxford Street, meeting Charing Cross Road, Tottenham Court Road (next to Tottenham Court Road station). It runs past Rathbone Place, Wardour Street and Great Portland Street to Oxford Circus, where it meets Regent Street. From there it continues past New Bond Street, Bond Street station and Vere Street, ending at Marble Arch. The route continues as Bayswater Road and Holland Park Avenue towards Shepherd's Bush.[1]

The road is within the London Congestion Charging Zone. It is part of the A40, most of which is a trunk road running from London to Fishguard (via Oxford, Cheltenham, Brecon and Haverfordwest). Like many roads in Central London that are no longer through routes, it is not signposted with that number.[1] Numerous bus routes run along Oxford Street, including 10, 25, 55, 73, 98, 390 and Night Buses N8, N55, N73, N98 and N207.[2]

History

Early history

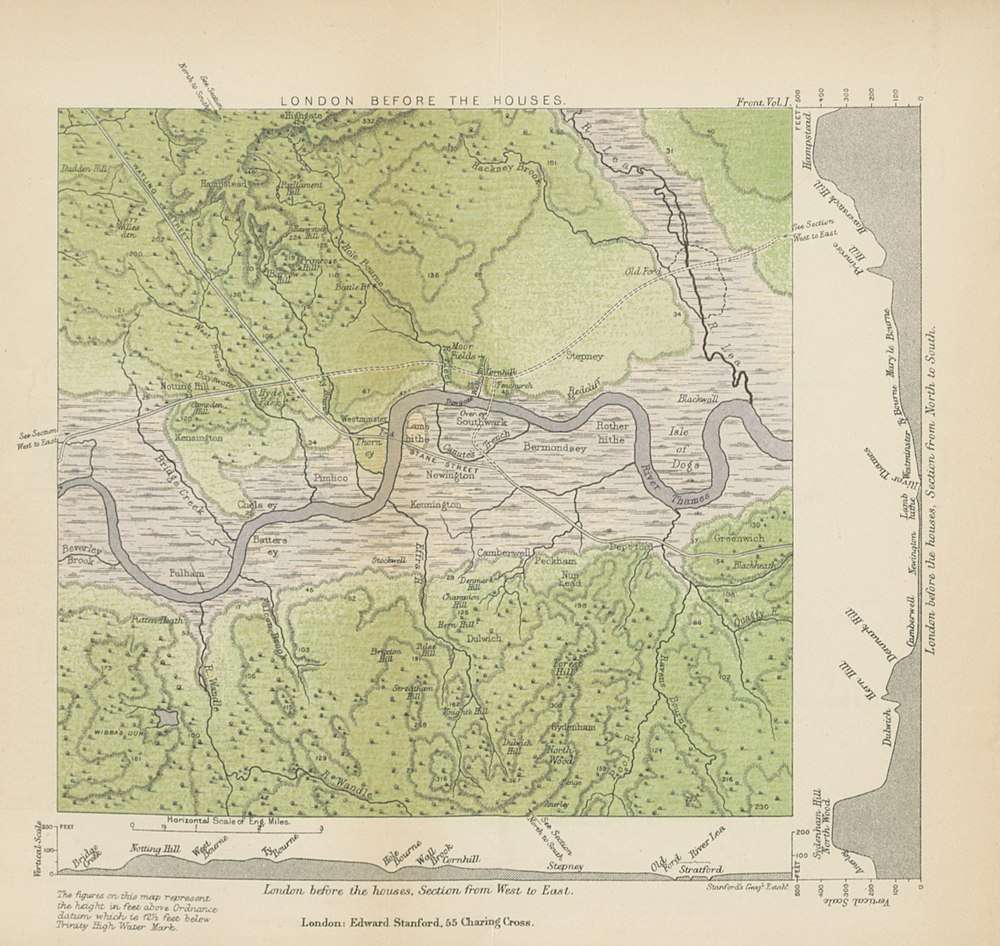

Oxford Street follows the route of a Roman road, the Via Trinobantina, which linked Calleva Atrebatum (near Silchester, Hampshire) with Camulodunum (now Colchester) via London and became one of the major routes in and out of the city.[3]

Between the 12th century and 1782, it was variously known as Tyburn Road (after the River Tyburn that crossed it north to south), Uxbridge Road (the name still used for the road between Shepherds Bush and Uxbridge), Worcester Road and Oxford Road.[4] At the western end, the road met the Tyburn gallows next to Marble Arch.[5] On Ralph Aggas' "Plan of London", published in the 16th century, the road is described partly as "The Waye to Uxbridge" followed by "Oxford Road", showing rural farmland at the present junction of Oxford Street and Rathbone Place. By 1678 it was known as the "King's Highway", and the "Road To Oxford" by 1682.[6][7]

Though a major coaching route, there were several obstacles along it, including the bridge over the Tyburn. A turnpike trust was established in the 1730s to improve upkeep of the road.[4] It became notorious as the route taken by prisoners on their final journey from Newgate Prison to the gallows at Tyburn. Spectators jeered as the prisoners were carted along the road, and could buy rope used in the executions from the hangman in taverns.[8] By about 1729, the road had become known as Oxford Street.[6]

Development began in the 18th century after many surrounding fields were purchased by the Earl of Oxford.[8] In 1739, a local gardener, Thomas Huddle, built property on the north side.[9] John Rocque's Map of London, published in 1746, shows urban buildings as far as North Audley Street, but only intermittent rural property beyond. Buildings were erected on the corner of Oxford Street and Davies Street in the 1750s.[10] Further development occurred between 1763 and 1793. The Pantheon, a place for public entertainment, opened at No. 173 in 1772.[9]

The street became popular for entertainment including bear-baiters, theatres and public houses.[11] However, it was not attractive to the middle and upper classes due to the nearby Tyburn gallows and the notorious St Giles rookery, or slum.[8] The gallows were removed in 1783, and by the end of the century, Oxford Street was built up from St Giles Circus to Park Lane, containing a mix of residential houses and entertainment.[8][9] The site of the Princess's Theatre that opened in 1840 is now occupied by Oxford Walk shopping area.[9]

Oxford Circus was designed as part of the development of Regent Street by the architect John Nash in 1810. The four quadrants of the circus were designed by Sir Henry Tanner and constructed between 1913 and 1928.[12]

Retail development

Oxford Street changed in character from residential to retail towards the end of the 19th century. Drapers, cobblers and furniture stores opened shops on the street, and some expanded into the first department stores. Street vendors sold tourist souvenirs during this time.[9] A plan in Tallis's London Street Views, published in the late 1830s, remarks that almost all the street, save for the far western end, was primarily retail.[4] John Lewis started in 1864 in small shop at No. 132,[13] while Selfridges opened on 15 March 1909 at No. 400.[14] Most of the southern side west of Davies Street was completely rebuilt between 1865 and 1890, allowing a more uniform freehold ownership.[4] By the 1930s, the street was almost entirely retail, a position that remains today. However, unlike nearby streets such as Bond Street and Park Lane, there remained a seedy element including street traders and prostitutes.[15] There are relatively few pubs in Oxford Street, perhaps due to the high rental values.

.jpg)

Oxford Street suffered considerable bombing during the Second World War. During the night and early hours of 17 to 18 September 1940, 268 Heinkel He 111 and Dornier Do 17 bombers targeted the West End, particularly Oxford Street. Many buildings were damaged, either from direct hits or subsequent fires, including four department stores: John Lewis, Selfridges, Bourne & Hollingsworth and Peter Robinson. George Orwell wrote in his diary for 24 September that Oxford Street was "completely empty of traffic, and only a few pedestrians", and saw "innumerable fragments of broken glass".[16] John Lewis caught fire again on 25 September and was reduced to a shell. It remained a bomb site for the remainder of the war and beyond, finally being demolished and rebuilt between 1958 and 1960. Peter Robinson partially reopened on 22 September, though the main storefront remained boarded up. The basement was converted into studios for the BBC Eastern Service. Orwell made several broadcasts here from 1941 to 1943.[16]

Selfridges was bombed again on 17 April 1941, suffering further damage, including the destruction of the Palm Court Restaurant. The basement was converted to a communications base, with a dedicated line run along Oxford Street to Whitehall allowing British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to make secure and direct telephone calls to the US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The store was damaged again on 6 December 1944 after a V2 rocket exploded on nearby Duke Street, causing its Christmas tree displays to collapse into the street outside. Damage was repaired and the shop re-opened the following day.[16]

Post-war

In September 1973 a shopping-bag bomb was detonated by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) at the offices of the Prudential Assurance Company, injuring six people.[17] A second bomb was detonated by the IRA next to Selfridges in December 1974, injuring three people and causing £1.5 million worth of damage.[18] Oxford Street was again targeted by the IRA in August 1975; an undiscovered bomb that had been booby trapped exploded without any injuries.[19] The IRA also detonated a bomb at the John Lewis department store in December 1992 along with another in nearby Cavendish Square, injuring four people.[20]

The human billboard Stanley Green began selling on Oxford Street in 1968, advertising his belief in the link of proteins to sexual libido and the dangers therein. He regularly patrolled the street with a placard headlined "less passion from less protein",[15] and advertised his pamphlet Eight Passion Proteins with Care until his death in 1993. His placards are now housed in the British Museum.[21]

Centre Point, just beyond the eastern end of Oxford Street next to Tottenham Court Road station, was designed by property developer Harry Hyams and opened in 1966. It failed to find a suitable tenant and remained empty for many years before being occupied by squatters who used it as a centre of protest against the lack of suitable accommodation in central London. In 2015, building work began to convert it into residential flats, with development expected to finish in 2017.[22]

Buildings

.jpg)

Oxford Street is home to a number of major department stores and flagship retail outlets, containing over 300 shops as of 2012.[23] It is the most frequently visited shopping street in Inner London, attracting over half a million daily visitors in 2014,[24] and is one of the most popular destinations in London for tourists, with an annual estimated turnover of over £1 billion.[25] It forms part of a shopping district in the West End of London, along with other streets including Covent Garden, Bond Street and Piccadilly.[26]

The New West End Company, formerly the Oxford Street Association, oversees stores and trade along the street; its objective is to make the place safe and desirable for shoppers. The group has been critical of overcrowding and the quality of shops and has clamped down on abusive traders, who were then refused licences.[25][27]

Several British retail chains regard their Oxford Street branch as the flagship store. Debenhams opened as Marshall & Snelgrove in 1870; in 1919 they merged with Debenhams, which had opened in nearby Wigmore Street in 1778. The company was owned by Burton between 1985 and 1998.[28] The London flagship store of the House of Fraser began as D H Evans in 1879 and moved to its current premises in 1935.[29] It was the first department store in the UK with escalators serving every floor.[30] Selfridges, Oxford Street, the second-largest department store in the UK and flagship of the Selfridges chain, has been in Oxford Street since 1909.[31]

Marks & Spencer has two stores on Oxford Street. The first, Marks & Spencer Marble Arch, is at the junction with Orchard Street. A second branch is between Regent Street and Tottenham Court Road, on the former site of the Pantheon.[32]

The music retailer HMV was opened at No. 363 Oxford Street in 1921 by Sir Edward Elgar. The Beatles made their first recording in London in 1962, when they cut a 78 rpm demo disc in the store.[33] A larger store at No. 150 was opened in 1986 by Bob Geldof, and was the largest music shop in the world, at 60,000 square feet (6,000 m2). As well as music and video retail, the premises supported live gigs in the store. Because of financial difficulties, the store closed in 2014, with all retail moving to No. 363.[34]

The 100 Club, in the basement of No. 100, has been run as a live music venue since 24 October 1942. It was thought to be safe from bombing threats because of its underground location, and played host to jazz musicians, including Glenn Miller. It was renamed the London Jazz Club in 1948, and subsequently the Humphrey Lyttelton Club after he took over the lease in the 1950s. Louis Armstrong played at the venue during this time. It became a key venue for the trad jazz revival, hosting gigs by Chris Barber and Acker Bilk. It was renamed the 100 Club in 1964 after Roger Horton bought a stake, adding an alcohol licence for the first time. The venue hosted gigs by several British blues bands, including the Who, the Kinks and the Animals. It was an important venue for punk rock in the UK and hosted the first British punk festival on 21 September 1976, featuring the Sex Pistols, the Damned and the Buzzcocks.[35]

The Tottenham is a Grade II* listed pub at No. 6 Oxford Street, near Tottenham Court Road. It was built in the mid-19th century and is the last remaining pub in the street, which once had 20.[36][37][38]

The London College of Fashion has an Oxford Street campus on John Prince's Street near Oxford Circus. The college is part of the University of the Arts London, formerly the London Institute.[39]

The cosmetics retailer Lush opened a store in 2015. Measuring 9,300 square feet (860 m2) and containing three floors, it is the company's largest retail premises.[40]

Transport links

Oxford Street is served by major bus routes and by four tube stations of the London Underground. From Marble Arch eastwards, the stations are:

- Marble Arch, on the Central line

- Bond Street, on the Central line and Jubilee line

- Oxford Circus, on the Central line, Bakerloo line and Victoria line

- Tottenham Court Road, on the Central line and Northern line

The four stations serve an average of 100 million passengers every year, with Oxford Circus being the busiest.[41]

Crossrail, a major project involving an east-west rail route across London, will have two stations serving Oxford Street, at Bond Street and Tottenham Court Road. Each station will be "double-ended", with exits through the existing tube station and also some distance away: to the east of Bond Street, in Hanover Square near Oxford Circus;[42] to the west of Tottenham Court Road, in Dean Street.[43]

Traffic

Oxford Street has been ranked as the most important retail location in Britain and the busiest shopping street in Europe.[44] The pavements are congested because of shoppers and tourists, many of whom arrive at a tube station, and the roadway is regularly blocked by buses.[45]

There is heavy competition between foot and bus traffic on Oxford Street, which is the main east-west bus corridor through Central London. Around 175,000 people get on or off a bus on Oxford Street every day, along with 43,000 further through passengers. Taxis are popular, particularly along the stretch between Oxford Circus and Selfridges.[44] Between 2009 and 2012, there were 71 accidents involving traffic and pedestrians.[46] In 2016, a report suggested buses generally did not travel faster than 4.6 miles per hour (7.4 km/h), compared to a typical pedestrian speed of 3.1 miles per hour (5.0 km/h).[47]

There have been several proposals to reduce congestion on Oxford Street. Horse-drawn vehicles were banned in 1931, and traffic signals were installed the same year.[48][49] To prevent congestion of buses, most of Oxford Street is designated a bus lane during peak hours and private vehicles are banned. This is only open to buses, taxis and two-wheeled vehicles between 7:00am and 7:00pm on all days except Sundays.[44] The ban was introduced experimentally in June 1972 and was considered a success, with an estimated increase of £250,000 in retail sales. However, the area is popular with unregulated rickshaws, which are a major cause of congestion in the area. Their slow speed, coupled with the narrowness of the street (buses are unable to pass them, causing long traffic queues) only add to the traffic woes.[50][51] In 2009, a new diagonal crossing opened at Oxford Circus, allowing pedestrians to cross from one corner of Oxford Street to the opposite without needing to cross twice or use an underpass. This doubles the pedestrian capacity at the junction.[52]

Pedestrianisation

From 2005 to 2012, Oxford Street was closed to motor traffic on VIP Day, (Very Important Pedestrians), a Saturday before Christmas. The scheme was popular and boosted sales by over £17m in 2012 but in 2013, the New West End Company announced that the scheme would not go ahead as it wanted to do "something new".[53] In 2014, Liberal Democrat members of the London Assembly proposed the street should be pedestrianised by 2020.[54]

In 2006, the New West End Company and the Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, proposed to pedestrianise the street with a tram service running end to end.[55] The next Mayor, Boris Johnson, elected in 2008, announced that the scheme was not cost effective, too disruptive and would not go ahead. In response to a request from Johnson, Transport for London (TfL) reduced bus flow by 10% in both 2009 and 2010.[56] The New West End Company called for a 33% reduction in bus movements.[57]

In 2014, TfL suggested that pedestrianisation may not be a suitable long-term measure due to Crossrail reducing the demand for bus services on the street and proposed banning all traffic except buses and cycles during peak shopping times.[45] Optimisation of traffic signals, including pedestrian countdown signals, was also proposed.[58] TfL is concerned that long-term traffic problems may affect trade, which competes with shopping centres such as Westfield London, Westfield Stratford City and the Brent Cross Shopping Centre.[46] In 2015, while campaigning for election as London Mayor, Labour's Sadiq Khan favoured pedestrianisation, which was supported by other parties.[59] After winning the election, he pledged the street would be completely pedestrianised by 2020.[47] In 2017, the project was brought forward to be completed by the end of the following year.[60] The plan has been disapproved by local residents, Westminster City Council and the Fitzrovia Business Association.[61][62]

Pollution

In 2014, a report by a King's College, London scientist showed that Oxford Street had the world's highest concentration of nitrogen dioxide pollution, at 135 micrograms per cubic metre of air (μg/m3). The figure was an average that included night-time, when traffic was much lower. At peak times during the day, levels up to 463 μg/m3 were recorded – over 11 times the permitted EU maximum of 40 μg/m3.[63][64] Because of diesel-powered traffic (buses and taxis), annual average nitrogen dioxide concentrations are around 180 μg/m3. This is 4.5 times the EU target of 40 μg/m3 (Council Directive 1999/30/EC).[65]

Crime

Oxford Street has suffered from high crime rates. In 2005, an internal Metropolitan Police report named it as the most dangerous street in Central London.[66] In 2012, an analysis of crime statistics revealed that Oxford Street was the shopping destination most surrounded by crime in the UK. During 2011, there were 656 vehicle crimes, 915 robberies, 2,597 violent crimes and 5,039 reported instances of anti-social behaviour.[67]

In 2014, the United Arab Emirates issued a travel advisory, warning Emirati citizens to avoid Oxford Street and other areas of Central London such as Bond Street and Piccadilly due to "pickpocketing, fraud and theft".[68][69] The advent of closed-circuit television has reduced the area's attraction to scam artists and illegal street traders.[70][71]

Christmas lights

.jpg)

Every Christmas, Oxford Street is decorated with festive lights. The tradition of Christmas lights began in 1959, five years after neighbouring Regent Street. There were no light displays in 1976 or 1977 because of economic recession, but the lights returned in 1978 when Oxford Street organised a laser display, and have continued every year since.[72]

Current practice involves a celebrity turning the lights on in mid- to late-November, and the lights remain until 6 January (Twelfth Night). The festivities were postponed in 1963 because of the assassination of John F. Kennedy and in 1989 to fit with Kylie Minogue's touring commitments.[72] In 2015, the lights were switched on earlier, on Sunday 1 November, resulting in an unusual closure of the street to all traffic.[73]

Listed buildings

Oxford Street has several Grade II listed buildings. In addition, the façades to Oxford Circus tube station are also listed.[74][75]

| Number | Grade | Year listed | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | II* | 1987 | The Tottenham[38] |

| 34 & 36 | II | 1987 | Built 1912[76] |

| 35 | II | 2009 | Built for Richards & Co. jewellers in 1909[77] |

| 105–109 | II | 1986 | Built c. 1887 for the hatter Henry Heath[78] |

| 133–135 | II | 2009 | Pembroke House, built 1911[79] |

| 147 | II | 2009 | Built in 1897 for the chemist John Robbins.[80] |

| 156–162 | II* | 1975 | Built 1906–08; an early example of a steel-framed structure[81] |

| 164–182 | II | 1973[82] | Former Waring & Gillow department store |

| 173 | II | 2009 | The Pantheon, now Marks and Spencer[32] |

| 219 | II | 2001[83] | |

| 313 | II | 1975 | Built c. 1870–1880[84] |

| 360–366 | II | 1987[85] | |

| 368–370 | II | 2008 | Early 20th-century construction with 1930s façade[86] |

.jpg) No. 147 Oxford Street

No. 147 Oxford Street.jpg) United Kingdom House

United Kingdom House

Cultural references

Oxford Street is mentioned in several Charles Dickens novels. In A Tale of Two Cities, as Oxford Road, it is described as having "very few buildings", though it was heavily built up by the late 18th century. It is also mentioned in Sketches by Boz and Bleak House.[87] Oxford Street is one of the London poet Letitia Elizabeth Landon's Scenes in London. In this poem the busy bustle of commercial life is interrupted by and contrasted with the procession of a military funeral.[88]

The street is a square on the British Monopoly game board, part of the green set (together with Regent Street and Bond Street). The streets were grouped together as they are all primarily retail areas.[8] In 1991, music manager and entrepreneur Malcolm McLaren produced The Ghosts of Oxford Street, a musical documentary about life and history in the local area.[89]

See also

- List of eponymous roads in London

- Somerset House (demolished 1915), on the corner of Oxford Street and Park Lane

References

Citations

- A40, London W1D UK to 537 Oxford St, London W1C 2QP, UK (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "Central London Bus Map" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Knight, Stephen (October 2014). Oxford Street – the case for pedestrianisation (PDF) (Report). p. 2. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- Oxford Street: The Development of the Frontage, in Survey of London: volume 40: The Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part 2 (The Buildings). 1980. pp. 171–173. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 610.

- "36". Tottenham Court Road, in Old and New London: Volume 4. 1878. pp. 467–480. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

"Rathbone Place, Oxford Street, 1718," fixes the date of its erection. As the "Tyburn Road" does not appear to have been generally known as "Oxford Street" till some ten or eleven years later

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 612.

- Moore 2003, p. 241.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 611.

- Oxford Street: The Development of the Frontage, in Survey of London: volume 40: The Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part 2 (The Buildings) – section 2. 1980. pp. 171–173. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- Bracken 2011, p. 178.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 610,685.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 443.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 828.

- Moore 2003, p. 243.

- "The Blitz: Oxford Street's store wars". BBC News. 6 September 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "Shopping-bag bomb explodes in London". The Miami News. 12 September 1973. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- "London's Oxford St. bombed". The Gazette. Montreal. 20 December 1974. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- "A Chronology of the Conflict – 1975". CAIN Web Service. Ulster University. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "United Kingdom : Two Bombs explode in Oxford Street". ITN News. 16 December 1992. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Moore 2003, pp. 243–244.

- Osborne, Hilary (26 January 2015). "Work begins on luxury flat conversion of London landmark Centre Point". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Kye, Simon (2012). GLA Economics (PDF) (Report). Greater London Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- TfL 2014, p. 136.

- Moore 2003, p. 245.

- Campbell, Sophie. "West End London shopping". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- "Oxford Street Revisited". Time Out. 1 May 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Glinert 2012, p. 304.

- Inwood 2012, p. 267.

- Piper & Jervis 2002, p. 81.

- Moore 2003, p. 242.

- "The Pantheon (Marks and Spencers), Westminster". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Inwood 2012, p. 269.

- Shaikh, Thair (14 January 2014). "HMV closes historic Oxford Street store". The Independent. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Kronenburg 2013, pp. 19–20.

- Sullivan 2000, p. 194.

- Jephcote, Geoff Brandwood & Jane (2008). London heritage pubs: an inside story. St. Albans: Campaign for Real Ale. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-85249-247-2.

- Historic England. "The Tottenham public house (1357394)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- "University of the Arts London". The Independent. 1 August 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "In pictures: Lush unveils radical new look on Oxford Street". Retail Week. 27 April 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Moore 2003, p. 251.

- "Bond Street Station – design". Crossrail. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- "Tottenham Court Road – design". Crossrail. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- TfL 2014, p. 138.

- TfL 2014, p. 137.

- TfL 2014, p. 141.

- "Oxford Street to be pedestrianised by 2020". BBC News. 14 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- "Traffic Regulations (London)". Hansard. 25 February 1931. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Traffic regulations, Oxford Street". Hansard. 1 July 1931. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Through traffic ban for Oxford Street". Commercial Motor. 30 June 1972. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Urban Transport Planning Expenditure". Hansard. 9 July 1973. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Oxford Circus 'X-crossing' opens". BBC News. 2 November 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- "Traffic-free shopping day in London's West End scrapped". BBC News. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Oxford Street doomed to decline, report claims". BBC News. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Mayor's Oxford Street tram vision". BBC. 31 August 2006. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "Streets ahead: Relieving congestion on Oxford Street, Regent Street and Bond Street" (PDF). London Assembly Transport Committee. 4 February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2010. See Appendix 1.

- "Way To Go January 2009". New West End Company. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- TfL 2014, p. 142.

- "London Mayoral candidates back the pedestrianisation of Oxford Street". BBC News. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- "London's Oxford Street could be traffic-free by December 2018, says mayor". BBC News. 6 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "Sadiq Khan's plan to make Oxford Street traffic-free halted by council". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- "Most local residents oppose or have concerns about Oxford Street plans". Fitzrovia News. 11 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- "Diesel fumes choke Tox-ford Street". The Sunday Times. 6 July 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- "Oxford Street air pollution 'highest in the world'". Air Quality Times. 7 July 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- "Developing a new Air Quality Strategy and Action Plan – Consultation on Issues" (PDF). Westminster City Council. August 2008. See p 10

- "Oxford St tops crime list". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- "Britain's crime hot spots revealed". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- "Wealthy UAE tourists warned to stay away from Oxford Street due to crime". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- "Emirati tourists warned of 'dangerous' Oxford Street". The Independent. 20 August 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- Moore 2003, p. 244.

- "Oxford, Regents and Bond Streets Safer Neighbourhoods team target illegal street traders". London Metropolitan Police. 8 November 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- "London's bright past". BBC News. 22 December 1997. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "Oxford Street Christmas Lights". Time Out. 12 October 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- "Listed Buildings in Westminster, Greater London, England". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "Listed buildings". Westminster City Council. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "34 and 36, Oxford Street W1, Westminster". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- "35, Oxford Street, Westminster". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- "105–109, Oxford Street W1". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "133–135, Oxford Street, Westminster". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "147, Oxford Street, Westminster". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "156–162, Oxford Street W1, Westminster". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "164–182, Oxford Street W1, Westminster". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "219, Oxford Street, Westminster". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- "313, Oxford Street, W1 – Westminster". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- "360–366, Oxford Street W1, Westminster". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- "368–370, Oxford Street, Westminster". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- Hayward 2013, p. 120.

-

- "The Ghosts of Oxford Street". Channel 4. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

Sources

- Bracken, G. Byrne (2011). Walking Tour London: Sketches of the city's architectural treasures ... Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-981-4435-36-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glinert, Ed (2012). The London Compendium. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7181-9204-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, John; Keay, Julia (2008). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-405-04924-5.

- Hayward, Arthur (2013). The Dickens Encyclopaedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-02758-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Inwood, Stephen (2012). Historic London: An Explorer's Companion. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-75252-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kronenburg, Robert (2013). Live Architecture: Venues, Stages and Arenas for Popular Music. ISBN 978-1-135-71916-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Tim (2003). Do Not Pass Go. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-943386-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Piper, David; Jervis, Fionnuala (2002). The Companion Guide to London. Companion Guides. ISBN 978-1-900639-36-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sullivan, Edward (2000). Evening Standard London Pub Bar Guide 1999. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-86840-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swinnerton, Jo (2004). The London Companion. Robson Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-86105-799-0.

esther rantzenoxford street christmas lights.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - London's street family: Theory and case studies (PDF) (Report). Transport for London. 2014. p. 138. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

Further reading

- John Timbs (1867), "Oxford Street", Curiosities of London (2nd ed.), London: J.C. Hotten, OCLC 12878129

- Herbert Fry (1880), "Oxford Street", London in 1880, London: David Bogue + New Oxford Street (bird's eye view)

- Findlay Muirhead, ed. (1922), "Oxford Street", London and its Environs (2nd ed.), London: Macmillan & Co., OCLC 365061

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oxford Street. |