Vikings

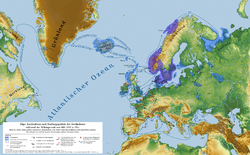

Vikings[lower-alpha 1] were the Norse people from southern Scandinavia (in present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden)[2][3][4] who from the late 8th to late 11th centuries raided and traded from their Northern European homelands across wide areas of Europe, and explored westward to Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland.[5][6][7] In modern English and other vernaculars, the term also commonly includes the inhabitants of Norse home communities during this period. This period of Nordic military, mercantile and demographic expansion had a profound impact on the early medieval history of Scandinavia, the British Isles, France, Estonia, Kievan Rus' and Sicily.[8]

| Part of a series on |

| Scandinavia |

|---|

|

Geography |

Expert sailors and navigators aboard their characteristic longships, Vikings voyaged as far as the Mediterranean littoral, North Africa, and the Middle East. After decades of exploration around the coasts and rivers of Europe, Vikings established Norse communities and governments scattered across north-western Europe, Belarus,[9] Ukraine[10] and European Russia, the North Atlantic islands all the way to the north-eastern coast of North America. The Vikings and their descendants established themselves as rulers and nobility in many areas of Europe. The Normans, descendants of Vikings who conquered and gave their name to what is now Normandy, also formed the aristocracy of England after the Norman conquest of England. While spreading Norse culture to foreign lands, they simultaneously brought home strong foreign cultural influences to Scandinavia, profoundly changing the historical development of both. During the Viking Age the Norse homelands were gradually consolidated from smaller kingdoms into three larger kingdoms, Denmark, Norway and Sweden.

Norse civilisation during the Viking Age was technologically, militarily and culturally advanced. Yet popular, modern conceptions of the Vikings—a term frequently applied casually to their modern Skandinavian descendants—often strongly differ from the complex, advanced civilisation of the Norsemen that emerges from archaeology and historical sources. A romanticised picture of Vikings as noble savages began to emerge in the 18th century; this developed and became widely propagated during the 19th-century Viking revival.[11][12] Perceived views of the Vikings as alternatively violent, piratical heathens or as intrepid adventurers owe much to conflicting varieties of the modern Viking myth that had taken shape by the early 20th century. Current popular representations of the Vikings are typically based on cultural clichés and stereotypes, complicating modern appreciation of the Viking legacy. These representations are rarely accurate—for example, there is no evidence that they wore horned helmets, a costume element that first appeared in Wagnerian opera.

Etymology

The form occurs as a personal name on some Swedish runestones. The stone of Tóki víking (Sm 10) was raised in memory of a local man named Tóki who got the name Tóki víking (Toki the Viking), presumably because of his activities as a Viking.[13] The Gårdstånga Stone (DR 330) uses the phrase "ÞeR drængaR waRu wiða unesiR i wikingu" (These men where well known i Viking),[14] referring to the stone's dedicatees as Vikings. The Västra Strö 1 Runestone has an inscription in memory of a Björn, who was killed when "i viking".[15] In Sweden there is a locality known since the Middle Ages as Vikingstad. The Bro Stone (U 617) was raised in memory of Assur who is said to have protected the land from Vikings (SaR vaR vikinga vorðr með Gæiti).[16][17] There is little indication of any negative connotation in the term before the end of the Viking Age.

Another less popular theory is that víking from the feminine vík, meaning "creek, inlet, small bay".[18] Various theories have been offered that the word viking may be derived from the name of the historical Norwegian district of Víkin, meaning "a person from Víkin".

However, there are a few major problems with this theory. People from the Viken area were not called "Viking" in Old Norse manuscripts, but are referred to as víkverir, ('Vík dwellers'). In addition, that explanation could explain only the masculine (víkingr) and not the feminine (víking), which is a serious problem because the masculine is easily derived from the feminine but hardly the other way around.[19][20][21]

Another etymology that gained support in the early twenty-first century, derives Viking from the same root as Old Norse vika, f. 'sea mile', originally 'the distance between two shifts of rowers', from the root *weik or *wîk, as in the Proto-Germanic verb *wîkan, 'to recede'.[22][23][24][25] This is found in the Proto-Nordic verb *wikan, 'to turn', similar to Old Icelandic víkja (ýkva, víkva) 'to move, to turn', with well-attested nautical usages.[26] Linguistically, this theory is better attested,[26] and the term most likely predates the use of the sail by the Germanic peoples of North-Western Europe, because the Old Frisian spelling shows that the word was pronounced with a palatal k and thus in all probability existed in North-Western Germanic before that palatalisation happened, that is, in the 5th century or before (in the western branch).[25][24]

In that case, the idea behind it seems to be that the tired rower moves aside for the rested rower on the thwart when he relieves him. The Old Norse feminine víking (as in the phrase fara í víking) may originally have been a sea journey characterised by the shifting of rowers, i.e. a long-distance sea journey, because in the pre-sail era, the shifting of rowers would distinguish long-distance sea journeys. A víkingr (the masculine) would then originally have been a participant on a sea journey characterised by the shifting of rowers. In that case, the word Viking was not originally connected to Scandinavian seafarers but assumed this meaning when the Scandinavians begun to dominate the seas.[22]

In Old English, the word wicing appears first in the Anglo-Saxon poem, Widsith, which probably dates from the 9th century. In Old English, and in the history of the archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen written by Adam of Bremen in about 1070, the term generally referred to Scandinavian pirates or raiders. As in the Old Norse usages, the term is not employed as a name for any people or culture in general. The word does not occur in any preserved Middle English texts. One theory made by the Icelander Örnolfur Kristjansson is that the key to the origins of the word is "wicinga cynn" in Widsith, referring to the people or the race living in Jórvík (York, in the ninth century under control by Norsemen), Jór-Wicings (note, however, that this is not the origin of Jórvík).[27]

The word Viking was introduced into Modern English during the 18th-century Viking revival, at which point it acquired romanticised heroic overtones of "barbarian warrior" or noble savage. During the 20th century, the meaning of the term was expanded to refer to not only seaborne raiders from Scandinavia and other places settled by them (like Iceland and the Faroe Islands), but also any member of the culture that produced said raiders during the period from the late 8th to the mid-11th centuries, or more loosely from about 700 to as late as about 1100. As an adjective, the word is used to refer to ideas, phenomena, or artefacts connected with those people and their cultural life, producing expressions like Viking age, Viking culture, Viking art, Viking religion, Viking ship and so on.[27]

The term ”Viking" that appeared in Northwestern Germanic sources in the Viking Age denoted pirates. According to some researchers, the term back then had no geographic or ethnic connotations that limited it to Scandinavia only. The term was instead used about anyone who to the Norse peoples appeared as a pirate. Therefore, the term had been used about Israelites on the Red Sea; Muslims encountering Scandinavians in the Mediterranean; Caucasian pirates encountering the famous Swedish Ingvar-Expedition, and Estonian pirates on the Baltic Sea. Thus the term "Viking" was supposedly never limited to a single ethnicity as such, but rather an activity.[28]

Other names

The Vikings were known as Ascomanni ("ashmen") by the Germans for the ash wood of their boats,[29] Dubgail and Finngail ( "dark and fair foreigners") by the Irish,[30] Lochlannach ("lake person") by the Gaels[31] and Dene (Dane) by the Anglo-Saxons.[32]

The scholarly consensus[33] is that the Rus' people originated in what is currently coastal eastern Sweden around the eighth century and that their name has the same origin as Roslagen in Sweden (with the older name being Roden).[34][35][36] According to the prevalent theory, the name Rus', like the Proto-Finnic name for Sweden (*Ruotsi), is derived from an Old Norse term for "the men who row" (rods-) as rowing was the main method of navigating the rivers of Eastern Europe, and that it could be linked to the Swedish coastal area of Roslagen (Rus-law) or Roden, as it was known in earlier times.[37][38] The name Rus' would then have the same origin as the Finnish and Estonian names for Sweden: Ruotsi and Rootsi.[38][39]

The Slavs and the Byzantines also called them Varangians (Russian: варяги, from Old Norse Væringjar, meaning 'sworn men', from vàr- "confidence, vow of fealty", related to Old English wær "agreement, treaty, promise", Old High German wara "faithfulness"[40]). Scandinavian bodyguards of the Byzantine emperors were known as the Varangian Guard. The Rus' initially appeared in Serkland in the 9th century, traveling as merchants along the Volga trade route, selling furs, honey, and slaves, as well as luxury goods such as amber, Frankish swords, and walrus ivory.[26] These goods were mostly exchanged for Arabian silver coins, called dirhams. Hoards of 9th century Baghdad-minted silver coins have been found in Sweden, particularly in Gotland.

During and after the Viking raid on Seville in 844 CE the Muslim chroniclers of al-Andalus referred to the Vikings as Magians (Arabic: al-Majus مجوس), conflating them with fire worshipping Zoroastrians from Persia.[41][42] When Ibn Fadlan was taken captive by Vikings in the Volga, he referred to them as Rus.[43][44][45]

The Franks normally called them Northmen or Danes, while for the English they were generally known as Danes or heathen and the Irish knew them as pagans or gentiles.[46]

Anglo-Scandinavian is an academic term referring to the people, and archaeological and historical periods during the 8th to 13th centuries in which there was migration to—and occupation of—the British Isles by Scandinavian peoples generally known in English as Vikings. It is used in distinction from Anglo-Saxon. Similar terms exist for other areas, such as Hiberno-Norse for Ireland and Scotland.

History

Viking Age

The Viking Age in Scandinavian history is taken to have been the period from the earliest recorded raids by Norsemen in 793 until the Norman conquest of England in 1066.[47] Vikings used the Norwegian Sea and Baltic Sea for sea routes to the south.

The Normans were descendants of those Vikings who had been given feudal overlordship of areas in northern France, namely the Duchy of Normandy, in the 10th century. In that respect, descendants of the Vikings continued to have an influence in northern Europe. Likewise, King Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, had Danish ancestors. Two Vikings even ascended to the throne of England, with Sweyn Forkbeard claiming the English throne in 1013 until 1014 and his son Cnut the Great being king of England between 1016 and 1035.[48][49][50][51][52]

Geographically, the Viking Age covered Scandinavian lands (modern Denmark, Norway and Sweden), as well as territories under North Germanic dominance, mainly the Danelaw, including Scandinavian York, the administrative centre of the remains of the Kingdom of Northumbria,[53] parts of Mercia, and East Anglia.[54] Viking navigators opened the road to new lands to the north, west and east, resulting in the foundation of independent settlements in the Shetland, Orkney, and Faroe Islands; Iceland; Greenland;[55] and L'Anse aux Meadows, a short-lived settlement in Newfoundland, circa 1000.[56] The Greenland settlement was established around 980, during the Medieval Warm Period, and its demise by the mid-15th century may have been partly due to climate change.[57] The Viking Rurik dynasty took control of territories in Slavic and Finno-Ugric-dominated areas of Eastern Europe; they annexed Kiev in 882 to serve as the capital of the Kievan Rus'.[58]

As early as 839, when Swedish emissaries are first known to have visited Byzantium, Scandinavians served as mercenaries in the service of the Byzantine Empire.[59] In the late 10th century, a new unit of the imperial bodyguard formed. Traditionally containing large numbers of Scandinavians, it was known as the Varangian Guard. The word Varangian may have originated in Old Norse, but in Slavic and Greek it could refer either to Scandinavians or Franks. In these years, Swedish men left to enlist in the Byzantine Varangian Guard in such numbers that a medieval Swedish law, Västgötalagen, from Västergötland declared no one could inherit while staying in "Greece"—the then Scandinavian term for the Byzantine Empire—to stop the emigration,[60] especially as two other European courts simultaneously also recruited Scandinavians:[61] Kievan Rus' c. 980–1060 and London 1018–1066 (the Þingalið).[61]

There is archaeological evidence that Vikings reached Baghdad, the centre of the Islamic Empire.[62] The Norse regularly plied the Volga with their trade goods: furs, tusks, seal fat for boat sealant, and slaves. Important trading ports during the period include Birka, Hedeby, Kaupang, Jorvik, Staraya Ladoga, Novgorod, and Kiev.

Scandinavian Norsemen explored Europe by its seas and rivers for trade, raids, colonization, and conquest. In this period, voyaging from their homelands in Denmark, Norway and Sweden the Norsemen settled in the present-day Faroe Islands, Iceland, Norse Greenland, Newfoundland, the Netherlands, Germany, Normandy, Italy, Scotland, England, Wales, Ireland, the Isle of Man, Estonia, Ukraine, Russia and Turkey, as well as initiating the consolidation that resulted in the formation of the present day Scandinavian countries.

In the Viking Age, the present day nations of Norway, Sweden and Denmark did not exist, but were largely homogeneous and similar in culture and language, although somewhat distinct geographically. The names of Scandinavian kings are reliably known for only the later part of the Viking Age. After the end of the Viking Age the separate kingdoms gradually acquired distinct identities as nations, which went hand-in-hand with their Christianisation. Thus the end of the Viking Age for the Scandinavians also marks the start of their relatively brief Middle Ages.

Expansion

Colonization of Iceland by Norwegian Vikings began in the ninth century. The first source mentioning Iceland and Greenland is a papal letter of 1053. Twenty years later, they appear in the Gesta of Adam of Bremen. It was not until after 1130, when the islands had become Christianized, that accounts of the history of the islands were written from the point of view of the inhabitants in sagas and chronicles.[63] The Vikings explored the northern islands and coasts of the North Atlantic, ventured south to North Africa, east to Kievan Rus (now – Ukraine, Belarus), Constantinople, and the Middle East.[64]

They raided and pillaged, traded, acted as mercenaries and settled colonies over a wide area.[65] Early Vikings probably returned home after their raids. Later in their history, they began to settle in other lands.[66] Vikings under Leif Erikson, heir to Erik the Red, reached North America and set up short-lived settlements in present-day L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, Canada. This expansion occurred during the Medieval Warm Period.[67]

Viking expansion into continental Europe was limited. Their realm was bordered by powerful tribes to the south. Early on, it was the Saxons who occupied Old Saxony, located in what is now Northern Germany. The Saxons were a fierce and powerful people and were often in conflict with the Vikings. To counter the Saxon aggression and solidify their own presence, the Danes constructed the huge defence fortification of Danevirke in and around Hedeby.[68]

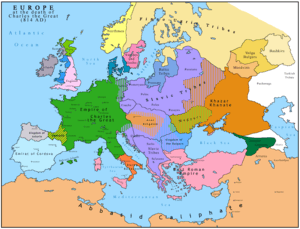

The Vikings witnessed the violent subduing of the Saxons by Charlemagne, in the thirty-year Saxon Wars of 772–804. The Saxon defeat resulted in their forced christening and the absorption of Old Saxony into the Carolingian Empire. Fear of the Franks led the Vikings to further expand Danevirke, and the defence constructions remained in use throughout the Viking Age and even up until 1864.[69]

The south coast of the Baltic Sea was ruled by the Obotrites, a federation of Slavic tribes loyal to the Carolingians and later the Frankish empire. The Vikings—led by King Gudfred—destroyed the Obotrite city of Reric on the southern Baltic coast in 808 AD and transferred the merchants and traders to Hedeby.[70] This secured Viking supremacy in the Baltic Sea, which continued throughout the Viking Age.

Motives

The motives driving the Viking expansion are a topic of much debate in Nordic history.

Researchers have suggested that Vikings may have originally started sailing and raiding due to a need to seek out women from foreign lands.[71][72][73][74] The concept was expressed in the 11th century by historian Dudo of Saint-Quentin in his semi imaginary History of The Normans.[75] Rich and powerful Viking men tended to have many wives and concubines; these polygynous relationships may have led to a shortage of eligible women for the average Viking male. Due to this, the average Viking man could have been forced to perform riskier actions to gain wealth and power to be able to find suitable women.[76][77][78] Viking men would often buy or capture women and make them into their wives or concubines.[79][80] Polygynous marriage increases male-male competition in society because it creates a pool of unmarried men who are willing to engage in risky status-elevating and sex seeking behaviors.[81][82] The Annals of Ulster states that in 821 the Vikings plundered an Irish village and "carried off a great number of women into captivity".[83]

One common theory posits that Charlemagne "used force and terror to Christianise all pagans", leading to baptism, conversion or execution, and as a result, Vikings and other pagans resisted and wanted revenge.[84][85][86][87][88] Professor Rudolf Simek states that "it is not a coincidence if the early Viking activity occurred during the reign of Charlemagne".[84][89] The penetration of Christianity into Scandinavia led to serious conflict dividing Norway for almost a century.[90]

Another explanation is that the Vikings exploited a moment of weakness in the surrounding regions. England suffered from internal divisions and was relatively easy prey given the proximity of many towns to the sea or to navigable rivers. Lack of organised naval opposition throughout Western Europe allowed Viking ships to travel freely, raiding or trading as opportunity permitted. The decline in the profitability of old trade routes could also have played a role. Trade between western Europe and the rest of Eurasia suffered a severe blow when the Western Roman Empire fell in the 5th century.[91] The expansion of Islam in the 7th century had also affected trade with western Europe.[92]

Raids in Europe, including raids and settlements from Scandinavia, were not unprecedented and had occurred long before the Vikings arrived. The Jutes invaded the British Isles three centuries earlier, pouring out from Jutland during the Age of Migrations, before the Danes settled there. The Saxons and the Angles did the same, embarking from mainland Europe. The Viking raids were, however, the first to be documented in writing by eyewitnesses, and they were much larger in scale and frequency than in previous times.[93]

Vikings themselves were expanding; although their motives are unclear, historians believe that scarce resources or a lack of mating opportunities were a factor.[94]

The "Highway of Slaves" was a term for a route that the Vikings found to have a direct pathway from Scandinavia to Constantinople and Baghdad while traveling on the Baltic Sea. With the advancements of their ships during the ninth century, the Vikings were able to sail to Kievan Rus and some northern parts of Europe.[95]

Jomsborg

Jomsborg was a semi-legendary Viking stronghold at the southern coast of the Baltic Sea (medieval Wendland, modern Pomerania), that existed between the 960s and 1043. Its inhabitants were known as Jomsvikings. Jomsborg's exact location, or its existence, has not yet been established, though it is often maintained that Jomsborg was somewhere on the islands of the Oder estuary.[96]

End of the Viking Age

While the Vikings were active beyond their Scandinavian homelands, Scandinavia was itself experiencing new influences and undergoing a variety of cultural changes.[97]

Emergence of Nation-States and Monetary Economies

By the late 11th century, royal dynasties were legitimised by the Catholic Church (which had had little influence in Scandinavia 300 years earlier) which were asserting their power with increasing authority and ambition, with the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden taking shape. Towns appeared that functioned as secular and ecclesiastical administrative centres and market sites, and monetary economies began to emerge based on English and German models.[98] By this time the influx of Islamic silver from the East had been absent for more than a century, and the flow of English silver had come to an end in the mid-11th century.[99]

Assimilation into Christendom

Christianity had taken root in Denmark and Norway with the establishment of dioceses in the 11th century, and the new religion was beginning to organise and assert itself more effectively in Sweden. Foreign churchmen and native elites were energetic in furthering the interests of Christianity, which was now no longer operating only on a missionary footing, and old ideologies and lifestyles were transforming. By 1103, the first archbishopric was founded in Scandinavia, at Lund, Scania, then part of Denmark.

The assimilation of the nascent Scandinavian kingdoms into the cultural mainstream of European Christendom altered the aspirations of Scandinavian rulers and of Scandinavians able to travel overseas, and changed their relations with their neighbours.

One of the primary sources of profit for the Vikings had been slave-taking from other European peoples. The medieval Church held that Christians should not own fellow Christians as slaves, so chattel slavery diminished as a practice throughout northern Europe. This took much of the economic incentive out of raiding, though sporadic slaving activity continued into the 11th century. Scandinavian predation in Christian lands around the North and Irish Seas diminished markedly.

The kings of Norway continued to assert power in parts of northern Britain and Ireland, and raids continued into the 12th century, but the military ambitions of Scandinavian rulers were now directed toward new paths. In 1107, Sigurd I of Norway sailed for the eastern Mediterranean with Norwegian crusaders to fight for the newly established Kingdom of Jerusalem, and Danes and Swedes participated energetically in the Baltic Crusades of the 12th and 13th centuries.[100]

Culture

A variety of sources illuminate the culture, activities, and beliefs of the Vikings. Although they were generally a non-literate culture that produced no literary legacy, they had an alphabet and described themselves and their world on runestones. Most contemporary literary and written sources on the Vikings come from other cultures that were in contact with them.[101] Since the mid-20th century, archaeological findings have built a more complete and balanced picture of the lives of the Vikings.[102][103] The archaeological record is particularly rich and varied, providing knowledge of their rural and urban settlement, crafts and production, ships and military equipment, trading networks, as well as their pagan and Christian religious artefacts and practices.

Literature and language

The most important primary sources on the Vikings are contemporary texts from Scandinavia and regions where the Vikings were active.[104] Writing in Latin letters was introduced to Scandinavia with Christianity, so there are few native documentary sources from Scandinavia before the late 11th and early 12th centuries.[105] The Scandinavians did write inscriptions in runes, but these are usually very short and formulaic. Most contemporary documentary sources consist of texts written in Christian and Islamic communities outside Scandinavia, often by authors who had been negatively affected by Viking activity.

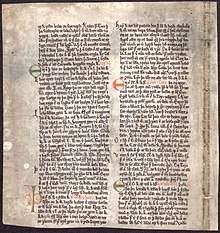

Later writings on the Vikings and the Viking Age can also be important for understanding them and their culture, although they need to be treated cautiously. After the consolidation of the church and the assimilation of Scandinavia and its colonies into the mainstream of medieval Christian culture in the 11th and 12th centuries, native written sources begin to appear in Latin and Old Norse. In the Viking colony of Iceland, an extraordinary vernacular literature blossomed in the 12th through 14th centuries, and many traditions connected with the Viking Age were written down for the first time in the Icelandic sagas. A literal interpretation of these medieval prose narratives about the Vikings and the Scandinavian past is doubtful, but many specific elements remain worthy of consideration, such as the great quantity of skaldic poetry attributed to court poets of the 10th and 11th centuries, the exposed family trees, the self images, the ethical values, that are contained in these literary writings.

Indirectly, the Vikings have also left a window open onto their language, culture and activities, through many Old Norse place names and words found in their former sphere of influence. Some of these place names and words are still in direct use today, almost unchanged, and shed light on where they settled and what specific places meant to them. Examples include place names like Egilsay (from Eigils ey meaning Eigil's Island), Ormskirk (from Ormr kirkja meaning Orms Church or Church of the Worm), Meols (from merl meaning Sand Dunes), Snaefell (Snow Fell), Ravenscar (Ravens Rock), Vinland (Land of Wine or Land of Winberry), Kaupanger (Market Harbour), Tórshavn (Thor's Harbour), and the religious centre of Odense, meaning a place where Odin was worshipped. Viking influence is also evident in concepts like the present-day parliamentary body of the Tynwald on the Isle of Man.

Common words in everyday English language, such as the names of weekdays (Thursday means Thor's day, Friday means Freya's day, Wednesday means Woden, or Odin's day, Tuesday means Týr's day, Týr being the Norse god of single combat, law, and justice), axle, crook, raft, knife, plough, leather, window, berserk, bylaw, thorp, skerry, husband, heathen, Hell, Norman and ransack stem from the Old Norse of the Vikings and give us an opportunity to understand their interactions with the people and cultures of the British Isles.[106] In the Northern Isles of Shetland and Orkney, Old Norse completely replaced the local languages and over time evolved into the now extinct Norn language. Some modern words and names only emerge and contribute to our understanding after a more intense research of linguistic sources from medieval or later records, such as York (Horse Bay), Swansea (Sveinn's Isle) or some of the place names in Normandy like Tocqueville (Toki's farm).[107]

Linguistic and etymological studies continue to provide a vital source of information on the Viking culture, their social structure and history and how they interacted with the people and cultures they met, traded, attacked or lived with in overseas settlements.[108][109] A lot of Old Norse connections are evident in the modern-day languages of Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Faroese and Icelandic.[110] Old Norse did not exert any great influence on the Slavic languages in the Viking settlements of Eastern Europe. It has been speculated that the reason for this was the great differences between the two languages, combined with the Rus' Vikings more peaceful businesses in these areas and the fact that they were outnumbered. The Norse named some of the rapids on the Dnieper, but this can hardly be seen from the modern names.[111][112]

Runestones

The Norse of the Viking Age could read and write and used a non-standardised alphabet, called runor, built upon sound values. While there are few remains of runic writing on paper from the Viking era, thousands of stones with runic inscriptions have been found where Vikings lived. They are usually in memory of the dead, though not necessarily placed at graves. The use of runor survived into the 15th century, used in parallel with the Latin alphabet.

The runestones are unevenly distributed in Scandinavia: Denmark has 250 runestones, Norway has 50 while Iceland has none.[113] Sweden has as many as between 1,700[113] and 2,500[114] depending on definition. The Swedish district of Uppland has the highest concentration with as many as 1,196 inscriptions in stone, whereas Södermanland is second with 391.[115][116]

The majority of runic inscriptions from the Viking period are found in Sweden. Many runestones in Scandinavia record the names of participants in Viking expeditions, such as the Kjula runestone that tells of extensive warfare in Western Europe and the Turinge Runestone, which tells of a war band in Eastern Europe.

Other runestones mention men who died on Viking expeditions. Among them include the England runestones (Swedish: Englandsstenarna) which is a group of about 30 runestones in Sweden which refer to Viking Age voyages to England. They constitute one of the largest groups of runestones that mention voyages to other countries, and they are comparable in number only to the approximately 30 Greece Runestones[117] and the 26 Ingvar Runestones, the latter referring to a Viking expedition to the Middle East. They were engraved in Old Norse with the Younger Futhark.

The Jelling stones date from between 960 and 985. The older, smaller stone was raised by King Gorm the Old, the last pagan king of Denmark, as a memorial honouring Queen Thyre.[118] The larger stone was raised by his son, Harald Bluetooth, to celebrate the conquest of Denmark and Norway and the conversion of the Danes to Christianity. It has three sides: one with an animal image, one with an image of the crucified Jesus Christ, and a third bearing the following inscription:

King Haraldr ordered this monument made in memory of Gormr, his father, and in memory of Thyrvé, his mother; that Haraldr who won for himself all of Denmark and Norway and made the Danes Christian.[119]

Runestones attest to voyages to locations such as Bath,[120] Greece (how the Vikings referred to the Byzantium territories generally),[121] Khwaresm,[122] Jerusalem,[123] Italy (as Langobardland),[124] Serkland (i.e. the Muslim world),[125] England[126] (including London[127]), and various places in Eastern Europe. Viking Age inscriptions have also been discovered on the Manx runestones on the Isle of Man.

Runic alphabet usage in modern times

The last known people to use the Runic alphabet were an isolated group of people known as the Elfdalians, that lived in the locality of Älvdalen in the Swedish province of Dalarna. They spoke the language of Elfdalian, the language unique to Älvdalen. The Elfdalian language differentiates itself from the other Scandinavian languages as it evolved much closer to Old Norse. The people of Älvdalen stopped using runes as late as the 1920s. Usage of runes therefore survived longer in Älvdalen than anywhere else in the world.[128] The last known record of the Elfdalian Runes is from 1929; they are a variant of the Dalecarlian runes, runic inscriptions that were also found in Dalarna.

Traditionally regarded as a Swedish dialect,[129] but by several criteria closer related to West Scandinavian dialects,[130] Elfdalian is a separate language by the standard of mutual intelligibility.[131][132][133] Although there is no mutual intelligibility, due to schools and public administration in Älvdalen being conducted in Swedish, native speakers are bilingual and speak Swedish at a native level. Residents in the area who speak only Swedish as their sole native language, neither speaking nor understanding Elfdalian, are also common. Älvdalen can be said to have had its own alphabet during the 17th and 18th century. Today there are about 2,000-3000 native speakers of Elfdalian.

Burial sites

There are numerous burial sites associated with Vikings throughout Europe and their sphere of influence—in Scandinavia, the British Isles, Ireland, Greenland, Iceland, Faeroe Islands, Germany, The Baltic, Russia, etc. The burial practices of the Vikings were quite varied, from dug graves in the ground, to tumuli, sometimes including so-called ship burials.

According to written sources, most of the funerals took place at sea. The funerals involved either burial or cremation, depending on local customs. In the area that is now Sweden, cremations were predominant; in Denmark burial was more common; and in Norway both were common.[134] Viking barrows are one of the primary source of evidence for circumstances in the Viking Age.[135] The items buried with the dead give some indication as to what was considered important to possess in the afterlife.[136] It is unknown what mortuary services were given to dead children by the Vikings.[137] Some of the most important burial sites for understanding the Vikings include:

- Norway: Oseberg; Gokstad; Borrehaugene.

- Sweden: Gettlinge gravfält; the cemeteries of Birka, a World Heritage Site;[138] Valsgärde; Gamla Uppsala; Hulterstad gravfält, near Alby; Hulterstad, Öland.

- Denmark: Jelling, a World Heritage Site; Lindholm Høje; Ladby ship; Mammen chamber tomb and hoard.

- Estonia: Salme ships – The largest ship burial ground ever uncovered.

- Scotland: Port an Eilean Mhòir ship burial; Scar boat burial, Orkney.

- Faroe Islands: Hov.

- Iceland: Mosfellsbær in Capital Region;[139][140] the boat burial in Vatnsdalur, Austur-Húnavatnssýsla.[134][141][142]

- Greenland: Brattahlíð.[143]

- Germany: Hedeby.

- Latvia: Grobiņa.

- Ukraine: the Black Grave.

- Russia: Gnezdovo.

Ships

There have been several archaeological finds of Viking ships of all sizes, providing knowledge of the craftsmanship that went into building them. There were many types of Viking ships, built for various uses; the best-known type is probably the longship.[144] Longships were intended for warfare and exploration, designed for speed and agility, and were equipped with oars to complement the sail, making navigation possible independently of the wind. The longship had a long, narrow hull and shallow draught to facilitate landings and troop deployments in shallow water. Longships were used extensively by the Leidang, the Scandinavian defence fleets. The longship allowed the Norse to go Viking, which might explain why this type of ship has become almost synonymous with the concept of Vikings.[145][146]

The Vikings built many unique types of watercraft, often used for more peaceful tasks. The knarr was a dedicated merchant vessel designed to carry cargo in bulk. It had a broader hull, deeper draught, and a small number of oars (used primarily to manoeuvre in harbours and similar situations). One Viking innovation was the 'beitass', a spar mounted to the sail that allowed their ships to sail effectively against the wind.[147] It was common for seafaring Viking ships to tow or carry a smaller boat to transfer crews and cargo from the ship to shore.

Ships were an integral part of the Viking culture. They facilitated everyday transportation across seas and waterways, exploration of new lands, raids, conquests, and trade with neighbouring cultures. They also held a major religious importance. People with high status were sometimes buried in a ship along with animal sacrifices, weapons, provisions and other items, as evidenced by the buried vessels at Gokstad and Oseberg in Norway[148] and the excavated ship burial at Ladby in Denmark. Ship burials were also practised by Vikings abroad, as evidenced by the excavations of the Salme ships on the Estonian island of Saaremaa.[149]

Well-preserved remains of five Viking ships were excavated from Roskilde Fjord in the late 1960s, representing both the longship and the knarr. The ships were scuttled there in the 11th century to block a navigation channel and thus protect Roskilde, then the Danish capital, from seaborne assault. The remains of these ships are on display at the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde.

In 2019, archaeologists uncovered two Viking boat graves in Gamla Uppsala. They also discovered that one of the boats still holds the remains of a man, a dog, and a horse, along with other items.[150] This has shed light on death rituals of Viking communities in the region.

Everyday life

Social structure

_(cropped).jpg)

Viking society was divided into the three socio-economic classes: Thralls, Karls and Jarls. This is described vividly in the Eddic poem of Rígsþula, which also explains that it was the God Ríg—father of mankind also known as Heimdallr—who created the three classes. Archaeology has confirmed this social structure.[151]

Thralls were the lowest ranking class and were slaves. Slaves comprised as much as a quarter of the population.[152] Slavery was of vital importance to Viking society, for everyday chores and large scale construction and also to trade and the economy. Thralls were servants and workers in the farms and larger households of the Karls and Jarls, and they were used for constructing fortifications, ramps, canals, mounds, roads and similar hard work projects. According to the Rigsthula, Thralls were despised and looked down upon. New thralls were supplied by either the sons and daughters of thralls or captured abroad. The Vikings often deliberately captured many people on their raids in Europe, to enslave them as thralls. The thralls were then brought back home to Scandinavia by boat, used on location or in newer settlements to build needed structures, or sold, often to the Arabs in exchange for silver. Other names for thrall were 'træl' and 'ty'.

Karls were free peasants. They owned farms, land and cattle and engaged in daily chores like ploughing the fields, milking the cattle, building houses and wagons, but used thralls to make ends meet. Other names for Karls were 'bonde' or simply free men.

The Jarls were the aristocracy of the Viking society. They were wealthy and owned large estates with huge longhouses, horses and many thralls. The thralls did most of the daily chores, while the Jarls did administration, politics, hunting, sports, visited other Jarls or went abroad on expeditions. When a Jarl died and was buried, his household thralls were sometimes sacrificially killed and buried next to him, as many excavations have revealed.[153]

In daily life, there were many intermediate positions in the overall social structure and it is believed that there must have been some social mobility. These details are unclear, but titles and positions like hauldr, thegn, landmand, show mobility between the Karls and the Jarls.

Other social structures included the communities of félag in both the civil and the military spheres, to which its members (called félagi) were obliged. A félag could be centred around certain trades, a common ownership of a sea vessel or a military obligation under a specific leader. Members of the latter were referred to as drenge, one of the words for warrior. There were also official communities within towns and villages, the overall defence, religion, the legal system and the Things.

Women

Women had a relatively free status in the Nordic countries of Sweden, Denmark and Norway, illustrated in the Icelandic Grágás and the Norwegian Frostating laws and Gulating laws.[154] The paternal aunt, paternal niece and paternal granddaughter, referred to as odalkvinna, all had the right to inherit property from a deceased man.[154] In the absence of male relatives, an unmarried woman with no son could inherit not only property but also the position as head of the family from a deceased father or brother. Such a woman was referred to as Baugrygr, and she exercised all the rights afforded to the head of a family clan—such as the right to demand and receive fines for the slaughter of a family member—until she married, by which her rights were transferred to her new husband.[154]

After the age of 20, an unmarried woman, referred to as maer and mey, reached legal majority and had the right to decide her place of residence and was regarded as her own person before the law.[154] An exception to her independence was the right to choose a marriage partner, as marriages were normally arranged by the family.[155] Examinations of Viking Age burials suggests that women lived longer, and nearly all well past the age of 35, as compared to previous times. Female graves from before the Viking Age in Scandinavia holds a proportional large number of remains from women aged 20 to 35, presumably due to complications of childbirth.[156]

Widows enjoyed the same independent status as unmarried women. A married woman could divorce her husband and remarry.[157] It was also socially acceptable for a free woman to cohabit with a man and have children with him without marrying him, even if that man was married; a woman in such a position was called frilla.[157]

There was no distinction made between children born inside or outside marriage: both had the right to inherit property after their parents, and there were no "legitimate" or "illegitimate" children.[157] Women had religious authority and were active as priestesses (gydja) and oracles (sejdkvinna).[158] They were active within art as poets (skalder)[158] and rune masters, and as merchants and medicine women.[158] They may also have been active within military office: the stories about shieldmaidens are unconfirmed, but some archaeological finds such as the Birka female Viking warrior may indicate that at least some women in military authority existed.[159] These liberties gradually disappeared after the introduction of Christianity,[160] and from the late 13th-century, they are no longer mentioned.[154]

Appearances

The three classes were easily recognisable by their appearances. Men and women of the Jarls were well groomed with neat hairstyles and expressed their wealth and status by wearing expensive clothes (often silk) and well crafted jewellery like brooches, belt buckles, necklaces and arm rings. Almost all of the jewellery was crafted in specific designs unique to the Norse (see Viking art). Finger rings were seldom used and earrings were not used at all, as they were seen as a Slavic phenomenon. Most Karls expressed similar tastes and hygiene, but in a more relaxed and inexpensive way.[151][161]

Archaeological findings throughout Scandinavia and Viking settlements in the British Isles support the idea of the well groomed and hygienic Viking. Burial with grave goods was a common practice in the Scandinavian world, through the Viking Age and well past the Christianization of the Norse peoples.[162] Within these burial sites and homesteads, combs, often made from antler, are a common find.[163]

The manufacturing of such antler combs was common, as at the Viking settlement at Dublin hundreds of examples of combs from the tenth-century have survived, suggesting that grooming was a common practice.[164] The manufacturing of such combs was also widespread throughout the Viking world, as examples of similar combs have been found at Viking settlements in Ireland,[165] England,[166] and Scotland.[167] The combs share a common visual appearance as well, with the extant examples often decorated with linear, interlacing, and geometric motifs, or other forms of ornamentation depending on the comb's period and type, but stylistically similar to Viking Age art.[168] The practice of grooming was a concern for all levels of Viking age society, as grooming products, combs, have been found in common graves as well as aristocratic ones.[169] Together, these grooming products indicate a conscious regard for appearance and hygiene, especially with the understanding of the regular bathing practices of Norse peoples.

Farming and cuisine

The sagas tell about the diet and cuisine of the Vikings,[170] but first hand evidence, like cesspits, kitchen middens and garbage dumps have proved to be of great value and importance. Undigested remains of plants from cesspits at Coppergate in York have provided much information in this respect. Overall, archaeo-botanical investigations have been undertaken increasingly in recent decades, as a collaboration between archaeologists and palaeoethno-botanists. This new approach sheds light on the agricultural and horticultural practices of the Vikings and their cuisine.[171]

.jpg)

The combined information from various sources suggests a diverse cuisine and ingredients. Meat products of all kinds, such as cured, smoked and whey-preserved meat,[172] sausages, and boiled or fried fresh meat cuts, were prepared and consumed.[173] There were plenty of seafood, bread, porridges, dairy products, vegetables, fruits, berries and nuts. Alcoholic drinks like beer, mead, bjórr (a strong fruit wine) and, for the rich, imported wine, were served.[174][175]

Certain livestock were typical and unique to the Vikings, including the Icelandic horse, Icelandic cattle, a plethora of sheep breeds,[176] the Danish hen and the Danish goose.[177][178] The Vikings in York mostly ate beef, mutton, and pork with small amounts of horse meat. Most of the beef and horse leg bones were found split lengthways, to extract the marrow. The mutton and swine were cut into leg and shoulder joints and chops. The frequent remains of pig skull and foot bones found on house floors indicate that brawn and trotters were also popular. Hens were kept for both their meat and eggs, and the bones of game birds such as black grouse, golden plover, wild ducks, and geese have also been found.[179]

Seafood was important, in some places even more so than meat. Whales and walrus were hunted for food in Norway and the north-western parts of the North Atlantic region, and seals were hunted nearly everywhere. Oysters, mussels and shrimps were eaten in large quantities and cod and salmon were popular fish. In the southern regions, herring was also important.[180][181][182]

Milk and buttermilk were popular, both as cooking ingredients and drinks, but were not always available, even at farms.[183] Milk came from cows, goats and sheep, with priorities varying from location to location,[184] and fermented milk products like skyr or surmjölk were produced as well as butter and cheese.[185]

Food was often salted and enhanced with spices, some of which were imported like black pepper, while others were cultivated in herb gardens or harvested in the wild. Home grown spices included caraway, mustard and horseradish as evidenced from the Oseberg ship burial[174] or dill, coriander, and wild celery, as found in cesspits at Coppergate in York. Thyme, juniper berry, sweet gale, yarrow, rue and peppercress were also used and cultivated in herb gardens.[171][186]

Vikings collected and ate fruits, berries and nuts. Apple (wild crab apples), plums and cherries were part of the diet,[187] as were rose hips and raspberry, wild strawberry, blackberry, elderberry, rowan, hawthorn and various wild berries, specific to the locations.[186] Hazelnuts were an important part of the diet in general and large amounts of walnut shells have been found in cities like Hedeby. The shells were used for dyeing, and it is assumed that the nuts were consumed.[171][183]

The invention and introduction of the mouldboard plough revolutionised agriculture in Scandinavia in the early Viking Age and made it possible to farm even poor soils. In Ribe, grains of rye, barley, oat and wheat dated to the 8th century have been found and examined, and are believed to have been cultivated locally.[188] Grains and flour were used for making porridges, some cooked with milk, some cooked with fruit and sweetened with honey, and also various forms of bread. Remains of bread from primarily Birka in Sweden were made of barley and wheat. It is unclear if the Norse leavened their breads, but their ovens and baking utensils suggest that they did.[189] Flax was a very important crop for the Vikings: it was used for oil extraction, food consumption and most importantly the production of linen. More than 40% of all known textile recoveries from the Viking Age can be traced as linen. This suggests a much higher actual percentage, as linen is poorly preserved compared to wool for example.[190]

The quality of food for common people was not always particularly high. The research at Coppergate shows that the Vikings in York made bread from whole meal flour—probably both wheat and rye—but with the seeds of cornfield weeds included. Corncockle (Agrostemma), would have made the bread dark-coloured, but the seeds are poisonous, and people who ate the bread might have become ill. Seeds of carrots, parsnip, and brassicas were also discovered, but they were poor specimens and tend to come from white carrots and bitter tasting cabbages.[187] The rotary querns often used in the Viking Age left tiny stone fragments (often from basalt rock) in the flour, which when eaten wore down the teeth. The effects of this can be seen on skeletal remains of that period.[189]

Sports

Sports were widely practised and encouraged by the Vikings.[191][192] Sports that involved weapons training and developing combat skills were popular. This included spear and stone throwing, building and testing physical strength through wrestling (see glima), fist fighting, and stone lifting. In areas with mountains, mountain climbing was practised as a sport. Agility and balance were built and tested by running and jumping for sport, and there is mention of a sport that involved jumping from oar to oar on the outside of a ship's railing as it was being rowed. Swimming was a popular sport and Snorri Sturluson describes three types: diving, long-distance swimming, and a contest in which two swimmers try to dunk one another. Children often participated in some of the sport disciplines and women have also been mentioned as swimmers, although it is unclear if they took part in competition. King Olaf Tryggvason was hailed as a master of both mountain climbing and oar-jumping, and was said to have excelled in the art of knife juggling as well.

Skiing and ice skating were the primary winter sports of the Vikings, although skiing was also used as everyday means of transport in winter and in the colder regions of the north.

Horse fighting was practised for sport, although the rules are unclear. It appears to have involved two stallions pitted against each other, within smell and sight of fenced-off mares. Whatever the rules were, the fights often resulted in the death of one of the stallions.

Icelandic sources refer to the sport of knattleik. A ball game akin to hockey, knattleik involved a bat and a small hard ball and was usually played on a smooth field of ice. The rules are unclear, but it was popular with both adults and children, even though it often led to injuries. Knattleik appears to have been played only in Iceland, where it attracted many spectators, as did horse fighting.

Hunting, as a sport, was limited to Denmark, where it was not regarded as an important occupation. Birds, deer, hares and foxes were hunted with bow and spear, and later with crossbows. The techniques were stalking, snare and traps and par force hunting with dog packs.

Games and entertainment

Both archaeological finds and written sources testify to the fact that the Vikings set aside time for social and festive gatherings.[191][192][193]

Board games and dice games were played as a popular pastime at all levels of society. Preserved gaming pieces and boards show game boards made of easily available materials like wood, with game pieces manufactured from stone, wood or bone, while other finds include elaborately carved boards and game pieces of glass, amber, antler or walrus tusk, together with materials of foreign origin, such as ivory. The Vikings played several types of tafl games; hnefatafl, nitavl (nine men's morris) and the less common kvatrutafl. Chess also appeared at the end of the Viking Age. Hnefatafl is a war game, in which the object is to capture the king piece—a large hostile army threatens and the king's men have to protect the king. It was played on a board with squares using black and white pieces, with moves made according to dice rolls. The Ockelbo Runestone shows two men engaged in Hnefatafl, and the sagas suggest that money or valuables could have been involved in some dice games.[191][193]

On festive occasions storytelling, skaldic poetry, music and alcoholic drinks, like beer and mead, contributed to the atmosphere.[193] Music was considered an art form and music proficiency as fitting for a cultivated man. The Vikings are known to have played instruments including harps, fiddles, lyres and lutes.[191]

Experimental archaeology

Experimental archaeology of the Viking Age is a flourishing branch and several places have been dedicated to this technique, such as Jorvik Viking Centre in the United Kingdom, Sagnlandet Lejre and Ribe Viking Center in Denmark, Foteviken Museum in Sweden or Lofotr Viking Museum in Norway. Viking-age reenactors have undertaken experimental activities such as iron smelting and forging using Norse techniques at Norstead in Newfoundland for example.[194]

On 1 July 2007, the reconstructed Viking ship Skuldelev 2, renamed Sea Stallion,[195] began a journey from Roskilde to Dublin. The remains of that ship and four others were discovered during a 1962 excavation in the Roskilde Fjord. Tree-ring analysis has shown the ship was built of oak in the vicinity of Dublin in about 1042. Seventy multi-national crew members sailed the ship back to its home, and Sea Stallion arrived outside Dublin's Custom House on 14 August 2007. The purpose of the voyage was to test and document the seaworthiness, speed, and manoeuvrability of the ship on the rough open sea and in coastal waters with treacherous currents. The crew tested how the long, narrow, flexible hull withstood the tough ocean waves. The expedition also provided valuable new information on Viking longships and society. The ship was built using Viking tools, materials, and much the same methods as the original ship.

Other vessels, often replicas of the Gokstad ship (full- or half-scale) or Skuldelev have been built and tested as well. The Snorri (a Skuldelev I Knarr), was sailed from Greenland to Newfoundland in 1998.[196]

Cultural assimilation

Elements of a Scandinavian identity and practices were maintained in settler societies, but they could be quite distinct as the groups assimilated into the neighboring societies. Assimilation to the Frankish culture in Normandy for example was rapid.[197] Links to a Viking identity remained longer in the remote islands of Iceland and the Faroes.[197]

Weapons and warfare

Knowledge about the arms and armour of the Viking age is based on archaeological finds, pictorial representation, and to some extent on the accounts in the Norse sagas and Norse laws recorded in the 13th century. According to custom, all free Norse men were required to own weapons and were permitted to carry them at all times. These arms indicated a Viking's social status: a wealthy Viking had a complete ensemble of a helmet, shield, mail shirt, and sword. However, swords were rarely used in battle, probably not sturdy enough for combat and most likely only used as symbolic or decorative items.[198][199]

A typical bóndi (freeman) was more likely to fight with a spear and shield, and most also carried a seax as a utility knife and side-arm. Bows were used in the opening stages of land battles and at sea, but they tended to be considered less "honourable" than melee weapons. Vikings were relatively unusual for the time in their use of axes as a main battle weapon. The Húscarls, the elite guard of King Cnut (and later of King Harold II) were armed with two-handed axes that could split shields or metal helmets with ease.

The warfare and violence of the Vikings were often motivated and fuelled by their beliefs in Norse religion, focusing on Thor and Odin, the gods of war and death.[200][201] In combat, it is believed that the Vikings sometimes engaged in a disordered style of frenetic, furious fighting known as berserkergang, leading them to be termed berserkers. Such tactics may have been deployed intentionally by shock troops, and the berserk-state may have been induced through ingestion of materials with psychoactive properties, such as the hallucinogenic mushrooms, Amanita muscaria,[202] or large amounts of alcohol.[203]

Trade

The Vikings established and engaged in extensive trading networks throughout the known world and had a profound influence on the economic development of Europe and Scandinavia.[204][205]

Except for the major trading centres of Ribe, Hedeby and the like, the Viking world was unfamiliar with the use of coinage and was based on so called bullion economy, that is, the weight of precious metals. Silver was the most common metal in the economy, although gold was also used to some extent. Silver circulated in the form of bars, or ingots, as well as in the form of jewellery and ornaments. A large number of silver hoards from the Viking Age have been uncovered, both in Scandinavia and the lands they settled.[206] Traders carried small scales, enabling them to measure weight very accurately, so it was possible to have a very precise system of trade and exchange, even without a regular coinage.[204]

Goods

Organized trade covered everything from ordinary items in bulk to exotic luxury products. The Viking ship designs, like that of the knarr, were an important factor in their success as merchants.[207] Imported goods from other cultures included:[208]

- Spices were obtained from Chinese and Persian traders, who met with the Viking traders in Russia. Vikings used homegrown spices and herbs like caraway, thyme, horseradish and mustard,[209] but imported cinnamon.

- Glass was much prized by the Norse. The imported glass was often made into beads for decoration and these have been found in the thousands. Åhus in Scania and the old market town of Ribe were major centres of glass bead production.[210][211][212]

- Silk was a very important commodity obtained from Byzantium (modern day Istanbul) and China. It was valued by many European cultures of the time, and the Vikings used it to indicate status such as wealth and nobility. Many of the archaeological finds in Scandinavia include silk.[213][214][215]

- Wine was imported from France and Germany as a drink of the wealthy, augmenting the regular mead and beer.

To counter these valuable imports, the Vikings exported a large variety of goods. These goods included:[208]

- Amber—the fossilised resin of the pine tree—was frequently found on the North Sea and Baltic coastline. It was worked into beads and ornamental objects, before being traded. (See also the Amber Road).

- Fur was also exported as it provided warmth. This included the furs of pine martens, foxes, bears, otters and beavers.

- Cloth and wool. The Vikings were skilled spinners and weavers and exported woollen cloth of a high quality.

- Down was collected and exported. The Norwegian west coast supplied eiderdowns and sometimes feathers were bought from the Samis. Down was used for bedding and quilted clothing. Fowling on the steep slopes and cliffs was dangerous work and was often lethal.[216]

- Slaves, known as thralls in Old Norse. On their raids, the Vikings captured many people, among them monks and clergymen. They were sometimes sold as slaves to Arab merchants in exchange for silver.

Other exports included weapons, walrus ivory, wax, salt and cod. As one of the more exotic exports, hunting birds were sometimes provided from Norway to the European aristocracy, from the 10th century.[216]

Many of these goods were also traded within the Viking world itself, as well as goods such as soapstone and whetstone. Soapstone was traded with the Norse on Iceland and in Jutland, who used it for pottery. Whetstones were traded and used for sharpening weapons, tools and knives.[208] There are indications from Ribe and surrounding areas, that the extensive medieval trade with oxen and cattle from Jutland (see Ox Road), reach as far back as c. 720 AD. This trade satisfied the Vikings' need for leather and meat to some extent, and perhaps hides for parchment production on the European mainland. Wool was also very important as a domestic product for the Vikings, to produce warm clothing for the cold Scandinavian and Nordic climate, and for sails. Sails for Viking ships required large amounts of wool, as evidenced by experimental archaeology. There are archaeological signs of organised textile productions in Scandinavia, reaching as far back as the early Iron Ages. Artisans and craftsmen in the larger towns were supplied with antlers from organised hunting with large-scale reindeer traps in the far north. They were used as raw material for making everyday utensils like combs.[216]

Legacy

Medieval perceptions

In England the Viking Age began dramatically on 8 June 793 when Norsemen destroyed the abbey on the island of Lindisfarne. The devastation of Northumbria's Holy Island shocked and alerted the royal courts of Europe to the Viking presence. "Never before has such an atrocity been seen," declared the Northumbrian scholar Alcuin of York.[217] Medieval Christians in Europe were totally unprepared for the Viking incursions and could find no explanation for their arrival and the accompanying suffering they experienced at their hands save the "Wrath of God".[218] More than any other single event, the attack on Lindisfarne demonised perception of the Vikings for the next twelve centuries. Not until the 1890s did scholars outside Scandinavia begin to seriously reassess the achievements of the Vikings, recognizing their artistry, technological skills, and seamanship.[219]

Norse Mythology, sagas, and literature tell of Scandinavian culture and religion through tales of heroic and mythological heroes. Early transmission of this information was primarily oral, and later texts relied on the writings and transcriptions of Christian scholars, including the Icelanders Snorri Sturluson and Sæmundur fróði. Many of these sagas were written in Iceland, and most of them, even if they had no Icelandic provenance, were preserved there after the Middle Ages due to the continued interest of Icelanders in Norse literature and law codes.

The 200-year Viking influence on European history is filled with tales of plunder and colonisation, and the majority of these chronicles came from western witnesses and their descendants. Less common, though equally relevant, are the Viking chronicles that originated in the east, including the Nestor chronicles, Novgorod chronicles, Ibn Fadlan chronicles, Ibn Rusta chronicles, and brief mentions by Photius, patriarch of Constantinople, regarding their first attack on the Byzantine Empire. Other chroniclers of Viking history include Adam of Bremen, who wrote, in the fourth volume of his Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum, "[t]here is much gold here (in Zealand), accumulated by piracy. These pirates, which are called wichingi by their own people, and Ascomanni by our own people, pay tribute to the Danish king." In 991, the Battle of Maldon between Viking raiders and the inhabitants of Maldon in Essex was commemorated with a poem of the same name.

Post-medieval perceptions

Early modern publications, dealing with what is now called Viking culture, appeared in the 16th century, e.g. Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (History of the northern people) of Olaus Magnus (1555), and the first edition of the 13th-century Gesta Danorum (Deeds of the Danes), by Saxo Grammaticus, in 1514. The pace of publication increased during the 17th century with Latin translations of the Edda (notably Peder Resen's Edda Islandorum of 1665).

In Scandinavia, the 17th-century Danish scholars Thomas Bartholin and Ole Worm and the Swede Olaus Rudbeck used runic inscriptions and Icelandic sagas as historical sources. An important early British contributor to the study of the Vikings was George Hickes, who published his Linguarum vett. septentrionalium thesaurus (Dictionary of the Old Northern Languages) in 1703–05. During the 18th century, British interest and enthusiasm for Iceland and early Scandinavian culture grew dramatically, expressed in English translations of Old Norse texts and in original poems that extolled the supposed Viking virtues.

The word "viking" was first popularised at the beginning of the 19th century by Erik Gustaf Geijer in his poem, The Viking. Geijer's poem did much to propagate the new romanticised ideal of the Viking, which had little basis in historical fact. The renewed interest of Romanticism in the Old North had contemporary political implications. The Geatish Society, of which Geijer was a member, popularised this myth to a great extent. Another Swedish author who had great influence on the perception of the Vikings was Esaias Tegnér, a member of the Geatish Society, who wrote a modern version of Friðþjófs saga hins frœkna, which became widely popular in the Nordic countries, the United Kingdom, and Germany.

Fascination with the Vikings reached a peak during the so-called Viking revival in the late 18th and 19th centuries as a branch of Romantic nationalism. In Britain this was called Septentrionalism, in Germany "Wagnerian" pathos, and in the Scandinavian countries Scandinavism. Pioneering 19th-century scholarly editions of the Viking Age began to reach a small readership in Britain, archaeologists began to dig up Britain's Viking past, and linguistic enthusiasts started to identify the Viking-Age origins of rural idioms and proverbs. The new dictionaries of the Old Norse language enabled the Victorians to grapple with the primary Icelandic sagas.[220]

Until recently, the history of the Viking Age was largely based on Icelandic sagas, the history of the Danes written by Saxo Grammaticus, the Russian Primary Chronicle, and Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib. Few scholars still accept these texts as reliable sources, as historians now rely more on archaeology and numismatics, disciplines that have made valuable contributions toward understanding the period.[221]

In 20th-century politics

The romanticised idea of the Vikings constructed in scholarly and popular circles in northwestern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries was a potent one, and the figure of the Viking became a familiar and malleable symbol in different contexts in the politics and political ideologies of 20th-century Europe.[222] In Normandy, which had been settled by Vikings, the Viking ship became an uncontroversial regional symbol. In Germany, awareness of Viking history in the 19th century had been stimulated by the border dispute with Denmark over Schleswig-Holstein and the use of Scandinavian mythology by Richard Wagner. The idealised view of the Vikings appealed to Germanic supremacists who transformed the figure of the Viking in accordance with the ideology of a Germanic master race.[223] Building on the linguistic and cultural connections between Norse-speaking Scandinavians and other Germanic groups in the distant past, Scandinavian Vikings were portrayed in Nazi Germany as a pure Germanic type. The cultural phenomenon of Viking expansion was re-interpreted for use as propaganda to support the extreme militant nationalism of the Third Reich, and ideologically informed interpretations of Viking paganism and the Scandinavian use of runes were employed in the construction of Nazi mysticism. Other political organisations of the same ilk, such as the former Norwegian fascist party Nasjonal Samling, similarly appropriated elements of the modern Viking cultural myth in their symbolism and propaganda.

Soviet and earlier Slavophile historians emphasized a Slavic rooted foundation in contrast to the Normanist theory of the Vikings conquering the Slavs and founding the Kievan Rus'.[224] They accused Normanist theory proponents of distorting history by depicting the Slavs as undeveloped primitives. In contrast, Soviet historians stated that the Slavs laid the foundations of their statehood long before the Norman/Viking raids, while the Norman/Viking invasions only served to hinder the historical development of the Slavs. They argued that Rus' composition was Slavic and that Rurik and Oleg' success was rooted in their support from within the local Slavic aristocracy.. After the dissolution of the USSR, Novgorod acknowledged its Viking history by incorporating a Viking ship into its logo.[225]

In modern popular culture

Led by the operas of German composer Richard Wagner, such as Der Ring des Nibelungen, Vikings and the Romanticist Viking Revival have inspired many creative works. These have included novels directly based on historical events, such as Frans Gunnar Bengtsson's The Long Ships (which was also released as a 1963 film), and historical fantasies such as the film The Vikings, Michael Crichton's Eaters of the Dead (movie version called The 13th Warrior), and the comedy film Erik the Viking. The vampire Eric Northman, in the HBO TV series True Blood, was a Viking prince before being turned into a vampire. Vikings appear in several books by the Danish American writer Poul Anderson, while British explorer, historian, and writer Tim Severin authored a trilogy of novels in 2005 about a young Viking adventurer Thorgils Leifsson, who travels around the world.

In 1962, American comic book writer Stan Lee and his brother Larry Lieber, together with Jack Kirby, created the Marvel Comics superhero Thor, which they based on the Norse god of the same name. The character is featured in the 2011 Marvel Studios film Thor and its sequels Thor: The Dark World and Thor: Ragnarok. The character also appears in the 2012 film The Avengers and its associated animated series.

The appearance of Vikings within popular media and television has seen a resurgence in recent decades, especially with the History Channel's series Vikings (2013), directed by Michael Hirst. The show has a loose grounding in historical facts and sources, but bases itself more so on literary sources, such as fornaldarsaga Ragnars saga loðbrókar, itself more legend than fact, and Old Norse Eddic and Skaldic poetry.[226] The events of the show frequently make references to the Völuspá, an Eddic poem describing the creation of the world, often directly referencing specific lines of the poem in the dialogue.[227] The show portrays some of the social realities of the medieval Scandinavian world, such as slavery[228] and the greater role of women within Viking society.[229] The show also addresses the topics of gender equity in Viking society with the inclusion of shield maidens through the character Lagertha, also based on a legendary figure.[230] Recent archaeological interpretations and osteological analysis of previous excavations of Viking burials has given support to the idea of the Viking woman warrior, namely the excavation and DNA study of the Birka female Viking warrior, within recent years. However, the conclusions remain contentious.

Vikings have served as an inspiration for numerous video games, such as The Lost Vikings (1993), Age of Mythology (2002), and For Honor (2017).[231] All three Vikings from The Lost Vikings series—Erik the Swift, Baleog the Fierce, and Olaf the Stout—appeared as a playable hero in the crossover title Heroes of the Storm (2015).[232] The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011) is an action role-playing video game heavily inspired by Viking culture.[233][234]

Modern reconstructions of Viking mythology have shown a persistent influence in late 20th- and early 21st-century popular culture in some countries, inspiring comics, movies, television series, role-playing games, computer games, and music, including Viking metal, a subgenre of heavy metal music.

Since the 1960s, there has been rising enthusiasm for historical reenactment. While the earliest groups had little claim for historical accuracy, the seriousness and accuracy of reenactors has increased. The largest such groups include The Vikings and Regia Anglorum, though many smaller groups exist in Europe, North America, New Zealand, and Australia. Many reenactor groups participate in live-steel combat, and a few have Viking-style ships or boats.

The Minnesota Vikings of the National Football League are so-named owing to the large Scandinavian population in the US state of Minnesota.

During the banking boom of the first decade of the twenty-first century, Icelandic financiers came to be styled as útrásarvíkingar (roughly 'raiding Vikings').[235][236][237]

Common misconceptions

Horned helmets

Apart from two or three representations of (ritual) helmets—with protrusions that may be either stylised ravens, snakes, or horns—no depiction of the helmets of Viking warriors, and no preserved helmet, has horns. The formal, close-quarters style of Viking combat (either in shield walls or aboard "ship islands") would have made horned helmets cumbersome and hazardous to the warrior's own side.

Historians therefore believe that Viking warriors did not wear horned helmets; whether such helmets were used in Scandinavian culture for other, ritual purposes, remains unproven. The general misconception that Viking warriors wore horned helmets was partly promulgated by the 19th-century enthusiasts of Götiska Förbundet, founded in 1811 in Stockholm.[238] They promoted the use of Norse mythology as the subject of high art and other ethnological and moral aims.

The Vikings were often depicted with winged helmets and in other clothing taken from Classical antiquity, especially in depictions of Norse gods. This was done to legitimise the Vikings and their mythology by associating it with the Classical world, which had long been idealised in European culture.

The latter-day mythos created by national romantic ideas blended the Viking Age with aspects of the Nordic Bronze Age some 2,000 years earlier. Horned helmets from the Bronze Age were shown in petroglyphs and appeared in archaeological finds (see Bohuslän and Vikso helmets). They were probably used for ceremonial purposes.[239]

.jpg)

Cartoons like Hägar the Horrible and Vicky the Viking, and sports kits such as those of the Minnesota Vikings and Canberra Raiders have perpetuated the myth of the horned helmet.[240]

Viking helmets were conical, made from hard leather with wood and metallic reinforcement for regular troops. The iron helmet with mask and mail was for the chieftains, based on the previous Vendel-age helmets from central Sweden. The only original Viking helmet discovered is the Gjermundbu helmet, found in Norway. This helmet is made of iron and has been dated to the 10th century.[241]

Barbarity

The image of wild-haired, dirty savages sometimes associated with the Vikings in popular culture is a distorted picture of reality.[7] Viking tendencies were often misreported, and the work of Adam of Bremen, among others, told largely disputable tales of Viking savagery and uncleanliness.[242]

Use of skulls as drinking vessels

There is no evidence that Vikings drank out of the skulls of vanquished enemies. This was a misconception based on a passage in the skaldic poem Krákumál speaking of heroes drinking from ór bjúgviðum hausa (branches of skulls). This was a reference to drinking horns, but was mistranslated in the 17th century[243] as referring to the skulls of the slain.[244]

Genetic legacy

Studies of genetic diversity provide indication of the origin and expansion of the Norse population. Haplogroup I-M253 (defined by specific genetic markers on the Y chromosome) mutation occurs with the greatest frequency among Scandinavian males: 35% in Norway, Denmark, and Sweden, and peaking at 40% in south-western Finland.[245] It is also common near the southern Baltic and North Sea coasts, and successively decreases further to the south geographically.

Female descent studies show evidence of Norse descent in areas closest to Scandinavia, such as the Shetland and Orkney islands.[246] Inhabitants of lands farther away show most Norse descent in the male Y-chromosome lines.[247]

A specialised genetic and surname study in Liverpool showed marked Norse heritage: up to 50% of males of families that lived there before the years of industrialisation and population expansion.[248] High percentages of Norse inheritance—tracked through the R-M420 haplotype—were also found among males in the Wirral and West Lancashire.[249] This was similar to the percentage of Norse inheritance found among males in the Orkney Islands.[250]

Recent research suggests that the Celtic warrior Somerled, who drove the Vikings out of western Scotland and was the progenitor of Clan Donald, may have been of Viking descent, a member of haplogroup R-M420.[251]

See also

- Faroese people

- Geats

- Gotlander

- Gutasaga

- Oeselians

- Proto-Norse language

- Scandinavian prehistory

- Swedes (Germanic tribe)

- Ushkuiniks, Novgorod's privateers

- Viking raid warfare and tactics

Notes

- Old English: wicing—"pirate",[1] Old Norse: víkingr

References

- Whitelock, Dorothy. Sweet's Anglo-Saxon Reader, OUP 1967, p. 392

-

- Mawer, Allen (1913). The Vikings. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 095173394X.