BT Tower

The BT Tower is a communications tower located in Fitzrovia, London, owned by BT Group. It has been previously known as the GPO Tower, the Post Office Tower and the Telecom Tower. The main structure is 177 metres (581 ft) high, with a further section of aerial rigging bringing the total height to 189 metres (620 ft).[2] Its Post Office code was YTOW.

| BT Tower | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the United Kingdom from 1964 to 1980[I] | |

| Preceded by | Millbank Tower |

| Surpassed by | Tower 42 |

| General information | |

| Type | Offices[1] |

| Location | London, W1T United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51.5215°N 0.1389°W |

| Construction started | 1961 |

| Completed | 1964[1] |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 189.0 metres (620.1 ft)[2] |

| Roof | 177.0 metres (580.7 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 37 |

| Lifts/elevators | 2 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Eric Bedford |

| Main contractor | Peter Lind & Company |

Upon completion in 1964, it overtook the Millbank Tower to become the tallest building in both London and the United Kingdom, titles that it held until 1980, when it in turn was overtaken by the NatWest Tower.

History

20th century

Commissioning and construction

The tower was commissioned by the General Post Office (GPO). Its primary purpose was to support the microwave aerials then used to carry telecommunications traffic from London to the rest of the country, as part of the General Post Office microwave network.

It replaced a much shorter steel lattice tower which had been built on the roof of the neighbouring Museum telephone exchange in the late 1940s to provide a television link between London and Birmingham. The taller structure was required to protect the radio links' "line of sight" against some of the tall buildings in London then in the planning stage. These links were routed via other GPO microwave stations at Harrow Weald, Bagshot, Kelvedon Hatch and Fairseat, and to places like the London Air Traffic Control Centre at West Drayton.

The tower was designed by the architects of the Ministry of Public Building and Works: the chief architects were Eric Bedford and G. R. Yeats. Typical for its time, the building is concrete clad in glass. The narrow cylindrical shape was chosen because of the requirements of the communications aerials: the building will shift no more than 25 centimetres (10 in) in wind speeds of up to 150 km/h (95 mph). Initially, the first 16 floors were for technical equipment and power. Above that was a 35-metre section for the microwave aerials, and above that were six floors of suites, kitchens, technical equipment, a revolving restaurant, and finally a cantilevered steel lattice tower. To prevent heat build-up, the glass cladding was of a special tint. The construction cost was £2.5 million.

Construction began in June 1961; owing to the building's height and its having a tower crane jib across the top virtually throughout the whole construction period, it gradually became a very prominent landmark that could be seen from almost anywhere in London. A question was raised in Parliament about the crane, in August 1963. Reginald Bennett MP asked the Minister of Public Buildings and Works, Geoffrey Rippon, how, when the crane on the top of the new Tower had fulfilled its purpose, he proposed to remove it. Rippon replied: "This is a matter for the contractors. The problem does not have to be solved for about a year but there appears to be no danger of the crane having to be left in situ."[3]

The tower was topped out on 15 July 1964, and officially opened by the then Prime Minister Harold Wilson on 8 October 1965. The main contractor was Peter Lind & Co Ltd.[4]

The tower was originally designed to be just 111 metres (364 ft) high; its foundations are sunk down through 53 metres of London clay, and are formed of a concrete raft 27 metres square, a metre thick, reinforced with six layers of cables, on top of which sits a reinforced concrete pyramid.[5]

Opening and use

The tower was officially opened to the public on 19 May 1966, by Tony Benn (then known as Anthony Wedgwood Benn) and Billy Butlin,[6][7] with HM the Queen visiting on 17 May 1966.[8]

As well as the communications equipment and office space, there were viewing galleries, a souvenir shop and a rotating restaurant on the 34th floor; this was called The Top of the Tower, and operated by Butlins. It made one revolution every 23 minutes.[9]

In its first year the Tower hosted just under one million visitors[10] and over 100,000 diners ate in the restaurant.[11]

1971 bombing

A bomb, responsibility for which was at first claimed by the Kilburn Batallion of the IRA,[12] exploded in the roof of the men's toilets at the Top of the Tower restaurant at 04:30 on 31 October 1971.[10] Responsibility for the bomb was also claimed by members of the Angry Brigade, a far-left anarchist collective.[13] That act resulted in the tower being largely closed to the general public.

The restaurant was closed to the public for security reasons a matter of months after the bombing in 1971. Later 1980 was the year in which Butlins' lease expired.[14] Public access to the building ceased in 1981.

The tower is sometimes used for corporate events, such as a children's Christmas party in December, Children in Need, and other special events; even though it is closed, the tower retains its revolving floor, providing a full panorama over London and the surrounding area.

Races up the tower

The first documented race up the tower's stairs was on 18 April 1968, between University College London and Edinburgh University; it was won by an Edinburgh runner in 4 minutes, 46 seconds.[15]

In 1969, eight university teams competed, with John Pearson from Manchester University winning in a time of 5 minutes, 6 seconds.[16]

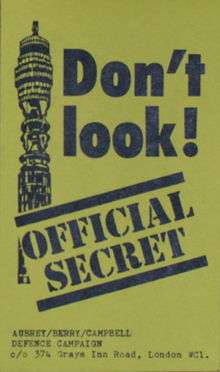

Secrecy

Due to its importance to the national communications network, information about the tower was designated an official secret. In 1978, the journalist Duncan Campbell was tried for collecting information about secret locations, and during the trial the judge ordered that the sites could not be identified by name; the Post Office Tower could only be referred to as 'Location 23'.[17]

It is often said that the tower did not appear on Ordnance Survey maps, despite being a 177-metre (581 ft) tall structure in the middle of central London that was open to the public for about 15 years.[18] However, this is incorrect; the 1:25,000 (published 1971) and 1:10,000 (published 1981) Ordnance Survey maps show the tower.[19] It is also shown in the London A–Z street atlas from 1984.[20]

In February 1993, the MP Kate Hoey used the tower as an example of trivial information being kept officially secret, and joked that she hoped parliamentary privilege allowed her to confirm that the tower existed and to state its street address.[21]

21st century

The tower is still in use, and is the site of a major UK communications hub. Microwave links have been replaced by subterranean optical fibre links for most mainstream purposes, but the former are still in use at the tower. The second floor of the base of the tower contains the TV Network Switching Centre which carries broadcasting traffic and relays signals between television broadcasters, production companies, advertisers, international satellite services and uplink companies. The outside broadcast control is located above the former revolving restaurant, with the kitchens on floor 35.

A renovation in the early 2000s introduced a 360° coloured lighting display at the top of the tower. Seven colours were programmed to vary constantly at night and intended to appear as a rotating globe to reflect BT's "connected world" corporate styling. The coloured lights give the tower a conspicuous presence on the London skyline at night. In October 2009, a 360° full-colour LED-based display system was installed at the top of the tower, to replace the previous colour projection system. The new display, referred to by BT as the "Information Band", is wrapped around the 36th and 37th floors of the tower, 167 m (548 ft) up, and comprises 529,750 LEDs arranged in 177 vertical strips, spaced around the tower. The display is the largest of its type in the world,[22] occupying an area of 280 m2 (3,000 sq ft) and with a circumference of 59 m (194 ft). The display is switched off at 10.30pm each day. On 31 October 2009, the screen began displaying a countdown of the number of days until the start of the London Olympics in 2012. In April 2019, the display spent almost a day displaying a Windows 7 error message.[23]

In October 2009, The Times reported that the rotating restaurant would be reopened in time for the 2012 London Olympics.[24] However, in December 2010, it was further announced that the plans to reopen had now been "quietly dropped" with no explanation as to the decision.[25] For the tower's 50th anniversary, the 34th floor was opened for three days from 3 to 5 October 2015 to 2,400 winners of a lottery.[26]

The BT Tower was given Grade II listed building status in 2003. Several of the defunct antennae attached to the building could not be removed unless the appropriate listed building consent was granted, as they were protected by this listing. In 2011, permission for the removal of the defunct antennas was approved on safety grounds as they were in a bad state of repair and the fixings were no longer secure.[27] In December 2011, the last of the antennas was removed leaving the core of the tower visible.

Entry to the building is by two high-speed lifts which travel at a top speed of 1400 feet per minute (7 metres per second (15.7 mph)), reaching the top of the building in under 30 seconds. An Act of Parliament was passed to vary fire regulations, allowing the building to be evacuated by using the lifts – unlike other buildings of the time.[28]

The tower is being used in a study to help monitor air quality in the capital. The aim is to measure pollutant levels above ground level to determine their source. One area of investigation is the long-range transport of fine particles from outside the city.[29]

Appearances in fiction

- In the film Three Hats for Lisa (1965) the characters take refuge in the tower. In the story it is under construction.

- Large portions of the Doctor Who serial The War Machines (1966) are set in and around the tower.

- In the film Smashing Time (1967) it appears to spin out of control, creating a fairground centrifugal effect for the occupants and short-circuiting the whole of London's power supply.

- The tower is featured in Stanley Donen's film Bedazzled (1967) as a vantage point from which Peter Cook, playing Satan, launches various forms of mischief.

- The tower is featured in The Goodies when it is toppled over by Twinkle the Giant Kitten in the episode "Kitten Kong" (1971). This scene was included in the title sequence of all later series.

- Characters in Iris Murdoch's novel The Black Prince (1973) frequently reference the Post Office Tower both literally and metaphorically. The restaurant is the setting for a lunch involving Bradley Pearson, the novel's first-person protagonist, and Julian Baffin, daughter of Pearson's friends, rival novelist Arnold Baffin and his wife Rachel. In his postscript, Francis Marloe refers to Pearson as a "sort of human Post Office Tower, erect and steely."

- The tower is destroyed in the James Herbert novel The Fog (1975) by a Boeing 747 whose captain has been driven mad by the eponymous fog.

- In The Judas Goat (1978), the fourth novel about Robert B. Parker's detective character Spenser, Spenser eats in the revolving restaurant even though it violates Spenser's Law (that the quality of meals in revolving restaurants never match their price).

- The tower is destroyed by an apparently alien robot from Mars – in fact a device operated by Baron Silas Greenback – in an episode of Danger Mouse (series 1, episode 11, 1981).

- In Alan Moore's graphic novel V for Vendetta (1982) the tower is headquarters for both the "Eye", and the "Ear", the visual and audio surveillance divisions of the government. The tower is destroyed through sabotage. It is also featured in the film adaptation (2005) although it is not destroyed. It is renamed Jordan Tower in the film and is the headquarters of the "British Television Network".

- Frank Muir's short story "The Law Is Not Concerned With Trifles" is set in the tower's revolving restaurant.

- Harry Adam Knight's sci-fi novel The Fungus (1985) climaxes in the tower, which undergoes a dramatic transformation: "It resembled an enormous mushroom. Fungus, dark and malevolent, had accumulated around its bulbous summit."

- In Patrick Keiller's film London (1992) the narrator claims the tower is a monument to the love affair between Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine, who lived nearby.

- It appears on the cover of, and features in, Saturday by Ian McEwan (2005).

- The bombing is a central plot feature of Hari Kunzru's novel My Revolutions (2007), in which the bomb is the work of political radicals who are never caught.

- In Daniel H. Wilson's 2011 novel Robopocalypse, the tower is used by the sentient artificial intelligence named Archos to control and jam satellite communications.

- In Sky1's adaptation of The Runaway (2011) the bombing of the tower is featured in episode 4.

- In J.K. Rowling's novel Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (1998), a newspaper report shows the enchanted Ford Anglia 105E flying over the BT Tower.

- In the film The Girl with All the Gifts (2016), the fungi pods grow up around the tower.

- In David Holman's novel ‘Countdown to Terror’ (2017) there is a scene in the Post Office Tower on the day of the 1969 Daily Mail Air Race which had the tower as its starting and finishing point.

See also

- List of masts

- List of tallest buildings and structures in Great Britain

- List of towers

- List of tallest buildings and structures in London

- Telecommunications towers in the UK

- Telecom infrastructure sharing

References

- "BT Tower". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- "We take an exclusive look behind the scenes at the BT Tower". Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Post Office Tower (Crane)". millbanksystems.com. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "BT Tower". lightstraw.co.uk. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "BT Tower: serving the nation 24 hours a day", BT, 1993

- "Post Office Tower Opening (1966)". YouTube. British Pathe. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Post Office Tower – 18 May 1966, Volume 728". Hansard. Parliament. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Queen Enjoys View From The Top". British Pathe. 17 May 1966. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FMPXmnK8G8E&t=142

- "Events in telecommunications history". BT PLC. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Glancey, Jonathan (7 October 2005). "The great communicator". Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "BBC ON THIS DAY – 31 – 1971: Bomb explodes in Post Office tower". BBC News. 3 April 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- "Bangor Daily News – Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- Virgin Media; Bt; Home Office; Broadband; Google; shock, Ace Reg reporter in career suicide; regulation, Sarko to use G8 presidency to promote net; laws, ISPs battle EU child pornography filter. "BT Tower to open for first time in 29 years". Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- "GPO Tower Race 1968: celebrating 50 years of UK tower running". Running UK. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "GPO Tower Race To Top 1969". British Pathe. 23 January 1969. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Grant, Thomas (2015). Jeremy Hutchinson's Case Histories. John Murray. p. 315.

- "London Telecom Tower, formerly BT Tower and Post Office Tower, Fitzrovia, West End, London". urban75. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- Kennett, Paul (August 2016). "Not so secret tower". Sheetlines. THE CHARLES CLOSE SOCIETY for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps (106): 27. (The Charles Close Society)

- A–Z London de luxe Atlas. Geographers' A–Z Map Company Ltd. 1984. p. 59.

- "Column 634". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 19 February 1993.

- "BT Tower of power: World's biggest LED screen set to light up the night". 31 October 2009. Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- at 20:50, Iain Thomson in San Francisco 8 Apr 2019. "BT Tower broadcasts error message to the nation as Windows displays admin's shame". www.theregister.co.uk. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- Goodman, Matthew (1 November 2009). "High times as BT reopens its revolving restaurant". The Times. London. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "BT Tower Restaurant Won't Re-Open". Londonist. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "Celebrating BT Tower's 50 ingenious years – come and visit the top of the BT Tower!". Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- "London's BT Tower to lose dish-shaped aerials". BBC News. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- "London Telecom Tower". Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- "BT Tower in pollution study". Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to BT Tower, London. |

- "Connected Earth: Learning Centre". Archived from the original on 6 April 2005. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- BT Tower (1964) at Structurae. Retrieved on 21 January 2015.

- "Peter Lind and Company – Building Contractors". Archived from the original on 29 April 2007. Retrieved 29 April 2007.

- Post Office Tower

- The official tower guide, archive film footage, and more.

- "The Tower from Conway Street QuickTime Panorama, British Tours ltd". Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "BT Tower photo feature on urban75". Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- 320 gigapixel panoramic view

- "Thirty-six Views of a London Tower..." A short film with the BT Tower in every shot.

- BT Tower building information & photos

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Millbank Tower |

Tallest Building in the United Kingdom 1967–1980 177 m |

Succeeded by NatWest Tower |

| Preceded by Millbank Tower |

Tallest Building in London 1967–1980 177 m |

Succeeded by NatWest Tower |