Tudor London

Henry Tudor, who seized the English throne as Henry VII in 1485, and married Elizabeth of York, put an end to the Wars of the Roses. Henry VII was a resolute and efficient monarch who centralised political power in the crown. He commissioned the celebrated "Henry VII Chapel" at Westminster Abbey, and continued the royal practice of borrowing funds from the City of London for his wars against the French. He repaid loans on their due dates, which was something of an innovation. Generally, however, he took little interest in enhancing London. Nonetheless, the comparative stability of the Tudor kingdom had long-term effects on the city, which grew rapidly during the 16th century. The nobility found that power and wealth were now best won by competing for favour at court, rather than by warring amongst themselves in the provinces as they had so often done in the past. The Tudor period is considered to have ended in 1603 with the death of Queen Elizabeth.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of London |

|

| See also |

|

|

Nonetheless Tudor London was often tumultuous by modern standards. In 1497 the pretender Perkin Warbeck, who claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, the younger brother of the boy monarch Edward V, encamped on Blackheath with his followers. At first there was panic among the citizens, but the king organised the defence of the city, the rebels dispersed, and Warbeck was soon captured and hanged at Tyburn.

The Reformation

The Reformation produced little bloodshed in London, with most of the higher classes co-operating to bring about a gradual shift to Protestantism. Before the Reformation, more than half of the area of London was occupied by monasteries, nunneries and other religious houses, and about a third of the inhabitants were monks, nuns and friars. Thus Henry VIII's "Dissolution of the Monasteries" had a profound effect on the city as nearly all of this property changed hands. The process started in the mid 1530s, and by 1538 most of the larger houses had been abolished. Holy Trinity Aldgate went to Lord Audley, and the Marquess of Winchester built himself a house in part of its precincts. The Charterhouse went to Lord North, Blackfriars to Lord Cobham, and the leper hospital of St Giles to Lord Dudley, while the king took for himself the leper hospital of St James, which was rebuilt as St James's Palace.[1] Henry took Cardinal Wolsey's house at Westminster, York Place, and converted and expanded it in stages until it filled the area of Whitehall with a disorganized ramble. Henry enclosed former lands of Westminster Abbey as a deer park, the present Hyde Park and St. James's Park. To the west lay the village of Kensington.

Shortly before his death, Henry refounded St Bartholomew's Hospital, but most of the large buildings were left unoccupied when he died in 1547. In the reign of Edward VI, many passed to the City Livery Companies in lieu of payment of crown debts, and in some cases the rents arising from them were applied to charitable purposes. Separately, in 1550 the City purchased the manor of Southwark, on the south bank of the Thames and refounded the monastery of St. Thomas as St. Thomas' Hospital. Christ's Hospital was established in this period, and Bridewell Palace was converted into a children's home and house of correction for women. The Dissolution was also highly profitable for favoured courtiers who were able to obtain property on generous terms. Much of this was intensively rebuilt, cramming the extra housing required by London's burgeoning population into every corner.

On the death of Edward VI in 1553, Lady Jane Grey was received at the Tower of London as queen, but the lord mayor, aldermen and recorder soon changed course and proclaimed Mary I of England queen instead. The following year the new monarch's decision to marry Philip II of Spain provoked an uprising led by Sir Thomas Wyatt, who took possession of Southwark, and later reached Charing Cross, on the road from Westminster to the City, which is now regarded as the fulcrum of London, before moving on to Ludgate. But there was no uprising in the City, and Wyatt surrendered. This demonstrates the crucial political importance of the City at that time, and the small importance of the districts outside the walls.

Elizabethan London

The coronation of Queen Elizabeth in 1558 ushered in the Elizabethan era. This is often considered the high point of the English Renaissance and Tudor culture.

The late 16th century, when William Shakespeare and his contemporaries lived and worked in London, was one of the most notable periods in the city's cultural history. There was considerable hostility to the development of the theatre, however. Public entertainments produced crowds, and crowds were feared by the authorities because they might become mobs, and by many ordinary citizens who dreaded that large gatherings might contribute to the spread of plague. Theatre itself was discountenanced by the increasingly influential Puritan strand in the nation. However, Queen Elizabeth loved plays, which were performed for her privately at Court, and approved of public performances of "such plays only as were fitted to yield honest recreation and no example of evil". On April 11, 1582, the Lords of the Council wrote to the Lord Mayor to the effect that, as "her Majesty sometimes took delight in those pastimes, it had been thought not unfit, having regard to the season of the year and the clearance of the city from infection, to allow of certain companies of players in London, partly that they might thereby attain more dexterity and perfection in that profession, the better to content her Majesty".[2]

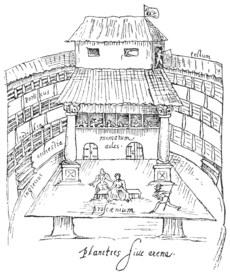

Nonetheless the theatres were mostly built outside of the City boundaries, beyond its jurisdiction. The first theatrical district was located north of the City wall, in Shoreditch. Here The Theatre and The Curtain were built, in 1576 and 1577 respectively. Later the south side of the river, which was already established as an area where less salubrious entertainments such as bear-baiting might be seen, became the main centre. Theatres on Bankside included The Globe, The Rose, The Swan, and The Hope. The Blackfriars Theatre, although within the walls, was also outside of the City's jurisdiction.

During the mostly calm later years of Elizabeth's reign, some of her courtiers and some of the wealthier citizens of London built themselves country residences in Middlesex, Essex, and Surrey. This was an early stirring of the villa movement, the taste for residences which were neither of the city nor on an agricultural estate, but when the last of the Tudors died in 1603, London was still very compact.

Trade and industry

During the Tudor period London was rapidly rising in importance amongst Europe's commercial centres, and its many small industries were booming, especially weaving. Trade expanded beyond Western Europe to Russia, the Levant, and the Americas. This was the period of mercantilism. Monopoly trading companies such as the Russia Company (1555) and the East India Company (1600) were established in London by Royal Charter. The latter, which ultimately came to rule much of India, was one of the key institutions in London, and in Britain as a whole, for two and a half centuries. In 1572 the Spanish destroyed the great commercial city of Antwerp, giving London first place among the North Sea ports. Immigrants arrived in London not just from all over England and Wales, but from abroad as well; for example, Huguenots came from France. The population rose from an estimated 50,000 in 1530 to about 225,000 in 1605.[1]

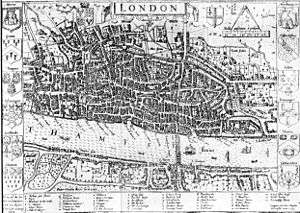

During the same time repeated ordinances, in futile attempts to check urban sprawl, forbade the building of new houses on less than 4 acres (16,000 m2) of ground in 1580, 1583, 1593, and 1605, applying to land as far as Chiswick or Tottenham,[1] the Tudor equivalents of green belt controls and five acre zoning. One result was increased subdividing and shoddy construction within the City, where the usual houses of the middle classes retained their medieval vernacular half-timbered construction, with dormers and gables and upper storeys that projected over the thoroughfares. In 1605 it was estimated that 75,000 lived in the City while 115,000 in the surrounding "Liberties", the inner suburbs where City writ did not run. Lincoln's Inn Fields remained fields, a "small Remaynder of Ayre" according to a Privy Council memorandum in 1617, when it was first proposed to build houses there.

The East End of London developed during this period in the unplanned strip development along existing highways. The topographer and city historian Stow recalled that Petticoat Lane in his youth had run among fields, flanked with hedgerows, but had become "a continual building of garden houses and small cottages" and Wapping "a continual street or filthy straight passage with alleys of small tenements".[1] In the East End, industries could be carried on beyond the supervision of London's guilds, the Livery Companies, still powerful and jealous of their jurisdiction.

During this period the first maps of London were drawn. The great bulk of the population was still enclosed in the City, living at a density which in the 21st century is unknown in the developed world. The old highway from the City to the royal court at Westminster, Strand, was lined with aristocrats’ mansions on its southern side. Their gardens ran down to the river, which remained the principal highway. "A very fine show" the Venetian ambassador reported in 1551, "but disfigured by the ruins of a multitude of churches and monasteries"[1] Though side lanes were beginning to be developed off Strand, the two settlements were otherwise separate: Westminster was a small fraction of the size of the City.

Other districts that are almost as central in 21st century London as are Westminster and the City themselves were still rural in the late 16th century. Covent Garden really was a market garden. Hospitals and convalescent homes were established in Holborn and Bloomsbury to take advantage of the country air. Islington and Hoxton were outlying villages.

In 1561, lightning struck Old St Paul's Cathedral. The roof was repaired, but the 500 ft (150 m) spire was never replaced. No new churches were built in London after the completion of St Giles Cripplegate until the Queen's chapel by Inigo Jones, begun in 1623. There was a need felt for new schools, following the break-up of monastic schools. St Paul's had been founded by John Colet in 1510. Christ's Hospital (1552, on the grounds of Greyfriars), was followed by Charterhouse in 1611. In 1565 Thomas Gresham founded a new mercantile exchange in the City, which was awarded the title the "Royal Exchange" by Queen Elizabeth in 1571. In April 1580 there was some damage to chimneys and walls in the Dover Straits earthquake of 1580.

See also

- History of London

- Timeline of 16th century London

- Copperplate map of London

- Woodcut map of London

References

- Nikolaus Pevsner, London I: The Cities of London and Westminster rev. edition 1962, Introduction, pp. 48-49.

- Rowse, A. L. (1950). The England of Elizabeth, p. 238. University of Wisconsin Press.

Further reading

- Walter Besant (1904), London in the Time of the Tudors, Survey of London, London: A. & C. Black

- G. E. Mitton (1908), Maps of Old London, London: A. and C. Black, OCLC 1476892, OL 23317516M

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to London in the 16th century. |