Khawak Pass

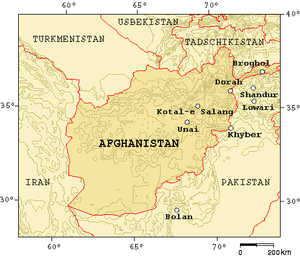

Khawak Pass (elevation 3,848 m (12,625 ft)) sits across the route heading to the northwest from near the head of the Panjshir Valley through the Hindu Kush range to northern Afghanistan via Andarab and Baghlan.[1]

| Khawak Pass | |

|---|---|

Mountain passes of Afghanistan | |

| Elevation | 4,370 m (14,337 ft) |

| Location | Afghanistan |

| Range | Hindu Kush |

| Coordinates | 35°39′47.1″N 69°47′14.1″E |

This is the route traditionally thought to have been followed by Alexander the Great in the spring of 329 BCE when he led his army from the Kabul Valley across the mountains to Bactria (later Tokharistan in the north). Vincent Smith states that Alexander took his troops across both the Khāwak and the Kaoshān or Kushan Pass.[2] According to some scholars, there is no proof of this.[3]

The Khāwak is most probably the pass used by the famous Chinese Buddhist pilgrim monk, Xuanzang, on his return from India to China in the early-7th century.[4][5] In 1333 Ibn Battuta crossed the pass on his journey to India. When dictating his account over twenty years later he remembered spreading felt cloth in front of his camels to prevent them sinking into the snow.[6]

It was also crossed by Timur (Tamerlane or Timur the Lame, 1336–1405), and by Captain John Wood on his return journey to the sources of the Oxus in the mid-19th century. It was the easternmost pass leading from the Kabul Valley into northern Afghanistan, and the most popular pass of this region.[7]

This pass, so important for the early history of Afghanistan, is now for the most part bypassed by the paved road that runs through the Salang tunnel under the Salang Pass, completed by the Soviets in 1964, at an elevation of about 3,400 m (11,200 ft). It links Charikar and Kabul with Kunduz, Khulm, Mazari Sharif and Termez.

Footnotes

- Hill (2009), pp. 560, 563.

- Smith (1914), p. 49.

- Vogelsang (2002), p. 9, n. 16; Hill (2009), pp. 564, 563

- Vogelsang (2002), p. 174.

- Wood (1872), p. lxiv (Xuanzang written as Hwen Thsang); Yule 1913, p. 258 (Xuanzang written as Hiuen Tsang)

- Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1855, pp. 84-85; Gibb 1971, pp. 586-587; Dunn 2005, p. 178

- Verma (1978), pp. 86 and nn. 155, 156; 264.

References

- Defrémery, C.; Sanguinetti, B.R. trans. and eds. (1855). Voyages d'Ibn Batoutah (Volume 3) (in French and Arabic). Paris: Société Asiatic.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dunn, Ross E. (2005). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24385-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibb, H.A.R. trans. and ed. (1971). The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354 (Volume 3). London: Hakluyt Society.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd centuries CE. Charleston, South Carolina: BookSurge. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Smith, Vincent A. (1914). The Early History of India from 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan conquest including the invasion of Alexander the Great (3rd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Verma, H. C. (1978). Medieval Routes to India: Baghdad to Delhi. Calcutta: Naya Prokash. OCLC 5220013.

- Vogelsang, Willem (2002). The Afghans. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-063119841-3.

- Wood, John (1872). A Journey to the Source of the River Oxus. With an essay on the Geography of the Valley of the Oxus by Colonel Henry Yule. London: John Murray.

- Yule, Henry (1913). Cathay and the way thither being a collection of medieval notices of China. Volume 4. London: Hakluyt Society.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)