Sivalik Hills

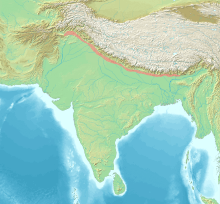

The Sivalik Hills, also known as Churia Hills, are a mountain range of the outer Himalayas that stretches from the Indus River about 2,400 km (1,500 mi) eastwards close to the Brahmaputra River, spanning across the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent. It is 10–50 km (6.2–31.1 mi) wide with an average elevation of 1,500–2,000 m (4,900–6,600 ft). Between the Teesta and Raidāk Rivers in Assam is a gap of about 90 km (56 mi). In some Sanskrit texts, the region is called Manak Parbat.[1] Sivalik literally means 'tresses of Shiva’.[2] Sivalik region is home to the Soanian archaeological culture.[3]

Geology

Geologically, the Sivalik Hills belong to the Tertiary deposits of the outer Himalayas.[4] They are chiefly composed of sandstone and conglomerate rock formations, which are the solidified detritus of the Himalayas[4] to their north; they are poorly consolidated. The remnant magnetisation of siltstones and sandstones indicates that they were deposited 16–5.2 million years ago. In Nepal, the Karnali River exposes the oldest part of the Shivalik Hills.[5]

They are the southernmost and geologically youngest east-west mountain chain of the Himalayas. They have many subranges and extend west from Arunachal Pradesh through Bhutan to West Bengal, and further westward through Nepal (here known as Churia Hills) and Uttarakhand, continuing into Himachal Pradesh and Kashmir. The hills are cut through at wide intervals by numerous large rivers flowing south from the Himalayas.

They are bounded on the south by a fault system called the Main Frontal Thrust, with steeper slopes on that side. Below this, the coarse alluvial Bhabar zone makes the transition to the nearly level plains. Rainfall, especially during the summer monsoon, percolates into the Bhabar, then is forced to the surface by finer alluvial layers below it in a zone of springs and marshes along the northern edge of the Terai or plains.[6]

North of the Sivalik Hills, the 1,500– to 3,000-meter Lesser Himalayas, also known as the Mahabharat Range, rise steeply along fault lines. In many places, the two ranges are adjacent, but in other places, structural valleys 10–20 km wide separate them.

Prehistory

Remains of the Lower Paleolithic (around 500,000 to 125,000 BP) Soanian culture were found in the Sivalik region.[7] Contemporary to the Acheulean, the Soanian culture is named after the Soan Valley in the Sivalik Hills of Pakistan. The Soanian archaeological culture is found across Sivalik region in present-day India, Nepal and Pakistan.[3]

Sivapithecus (a kind of ape, formerly known as Ramapithecus) is among many fossil finds in the Sivalik region.

The Sivalik Hills are also among the richest fossil sites for large animals anywhere in Asia; the hills had revealed that all kinds of animals lived there. They were early ancestors to the sloth bear; Sivatherium, an ancient giraffe; and Megalochelys atlas, a giant tortoise named the Sivaliks giant tortoise; amongst other creatures.

A number of fossil ratites were reported from the Sivalik Hills, including the extinct Asian ostrich, Dromaius sivalensis and Hypselornis. However, the latter two species were named only from toe bones that have since been identified as belonging to an ungulate mammal and a crocodilian, respectively.[8]

Demographics

Low population densities in the Sivalik Hills and along the steep southern slopes of the Lower Himalayan Range, plus virulent malaria in the damp forests on their fringes, create a cultural, linguistic, and political buffer zone between dense populations in the plains to the south and the "hills" beyond the Mahabharat escarpment, isolating the two populations from each other and enabling different evolutionary paths with respect to language, race, and culture.

People of the Lepcha tribe inhabit the Sikkim and Darjeeling areas.

In culture

The Indian Navy's Shivalik-class frigate is named after these ranges.

See also

- Margalla Hills – subrange in Islamabad region

- Shivalik Fossil Park

- Frederick Walter Champion, forester and wildlife photographer, was posted here after World War I until 1947.

- Dundwa Range – a subrange separating Deukhuri, an Inner Terai valley in western Nepal, from the Outer Terai in Balrampur and Shravasti districts, Uttar Pradesh

- The great green wall of Aravalli

- Leopards of Haryana

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shivalik Hills. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Siwalik Hills. |

- Kohli, M. S. (2002). "Shivalik Range". Mountains of India: Tourism, Adventure and Pilgrimage. Indus Publishing. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-81-7387-135-1.

- Balokhra, J. M. (1999). The Wonderland of Himachal Pradesh (Revised and enlarged fourth ed.). New Delhi: H. G. Publications. ISBN 9788184659757.

- Chauhan, P. (2016). "A decade of paleoanthropology in the Indian Subcontinent. The Soanian industry reassessed". In Schug, G. R.; Walimbe, S. R. (eds.). A Companion to South Asia in the Past. Oxford, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-119-05547-1.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 163–164.

- Gautam, P., Fujiwara, Y. (2000). "Magnetic polarity stratigraphy of Siwalik Group sediments of Karnali River section in western Nepal". Geophysical Journal International. 142 (3): 812–824. doi:10.1046/j.1365-246x.2000.00185.x.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Mani, M.S. (2012). Ecology and Biogeography in India. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 690.

- Lycett, S. J. (2007). "Is the Soanian techno-complex a Mode 1 or Mode 3 phenomenon? A morphometric assessment". Journal of Archaeological Science. 34 (9): 1434. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.11.001.

- Lowe, P. R. (1929). "Some remarks on Hypselornis sivalensis Lydekker". Ibis. 71 (4): 571–576. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1929.tb08775.x.