Sundarbans

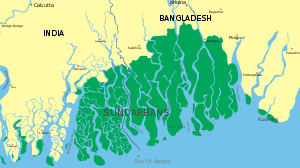

The Sundarbans is a mangrove area in the delta formed by the confluence of the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna Rivers in the Bay of Bengal. It spans from the Hooghly River in India's state of West Bengal to the Baleswar River in Bangladesh. It comprises closed and open mangrove forests, agriculturally used land, mudflats and barren land, and is intersected by multiple tidal streams and channels. Four protected areas in the Sundarbans are enlisted as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, viz. Sundarbans National Park, Sundarbans West, Sundarbans South and Sundarbans East Wildlife Sanctuaries.[3]

| Sundarbans | |

|---|---|

Deer and mangroves in the Sundarbans | |

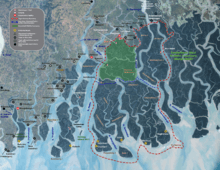

Location of the Sunderbans, spanning across the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta | |

| Location | West Bengal, India and Khulna Division, Bangladesh |

| Nearest city | Khulna, Satkhira, Bagerhat |

| Coordinates | 21°57′N 89°11′E |

| Governing body | Government of Bangladesh and Government of India |

| Official name | Sundarbans National Park |

| Location | South 24 Parganas and North 24 Parganas districts, West Bengal, India |

| Includes | |

| Criteria | Natural: (ix)(x) |

| Reference | 452 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th session) |

| Area | 133,010 ha (513.6 sq mi) |

| Coordinates | 21°56′42″N 88°53′45″E |

| Official name | The Sundarbans |

| Location | Khulna Division, Bangladesh |

| Includes |

|

| Criteria | Natural: (ix)(x) |

| Reference | 798 |

| Inscription | 1997 (21st session) |

| Area | 139,500 ha (539 sq mi) |

| Coordinates | 21°57′N 89°11′E |

| Official name | Sundarbans Reserved Forest |

| Designated | 21 May 1992 |

| Reference no. | 560[1] |

| Official name | Sundarban Wetland |

| Designated | 30 January 2019 |

| Reference no. | 2370[2] |

The Sundarbans mangrove forest covers an area of about 10,000 km2 (3,900 sq mi), of which forests in Bangladesh's Khulna Division extend over 6,017 km2 (2,323 sq mi) and in West Bengal, they extend over 4,260 km2 (1,640 sq mi) across the South 24 Parganas and North 24 Parganas districts.[4] The most abundant tree species are sundri (Heritiera fomes) and gewa (Excoecaria agallocha). The forests provide habitat to 453 faunal wildlife, including 290 bird, 120 fish, 42 mammal, 35 reptile and eight amphibian species.[5]

Despite a total ban on all killing or capture of wildlife other than fish and some invertebrates, it appears that there is a consistent pattern of depleted biodiversity or loss of species in the 20th century, and that the ecological quality of the forest is declining.[6] The Directorate of Forest is responsible for the administration and management of Sundarban National Park in West Bengal. In Bangladesh, a Forest Circle was created in 1993 to preserve the forest, and Chief Conservators of Forests have been posted since. Despite preservation commitments from both Governments, the Sunderbans are under threat from both natural and human-made causes. In 2007, the landfall of Cyclone Sidr damaged around 40% of the Sundarbans. The forest is also suffering from increased salinity due to rising sea levels and reduced freshwater supply. Again in May 2009 Cyclone Aila devastated Sundarban with massive casualties. At least 100,000 people were affected by this cyclone.[7][8] The proposed coal-fired Rampal power station situated 14 km (8.7 mi) north of the Sundarbans at Rampal Upazila of Bagerhat District in Khulna, Bangladesh, is anticipated to further damage this unique mangrove forest according to a 2016 report by UNESCO.[9]

Etymology

The Bengali name Sundarban Bengali: সুন্দরবন means "beautiful forest."[10][11] It may have been derived from the word Sundari or Sundri, the local name of the mangrove species Heritiera fomes. Alternatively, it has been proposed that the name is a corruption of Samudraban, Shomudrobôn ("Sea Forest"), or Chandra-bandhe, the name of a tribe.[12]

History

The history of the area can be traced back to 200–300 AD. A ruin of a city built by Chand Sadagar has been found in the Baghmara Forest Block. During the Mughal period, the Mughal Emperors leased the forests of the Sundarbans to nearby residents. Many criminals took refuge in the Sundarbans from the advancing armies of Emperor Akbar. Many have been known to be attacked by tigers.[13] Many of the buildings which were built by them later fell to hands of Portuguese pirates, salt smugglers and dacoits in the 16th and 17th centuries. Evidence of the fact can be traced from the ruins at Netidhopani and other places scattered all over Sundarbans.[14] The legal status of the forests underwent a series of changes, including the distinction of being the first mangrove forest in the world to be brought under scientific management. The area was mapped first in Persian, by the Surveyor General as early as 1769 following soon after proprietary rights were obtained from the Mughal Emperor Alamgir II by the British East India Company in 1757. Systematic management of this forest tract started in the 1860s after the establishment of a Forest Department in the Province of Bengal, in British India. The management was entirely designed to extract whatever treasures were available, but labour and lower management mostly were staffed by locals, as the British had no expertise or adaptation experience in mangrove forests.[15]

The first Forest Management Division to have jurisdiction over the Sundarbans was established in 1869. In 1875 a large portion of the mangrove forests was declared as reserved forests under the Forest Act, 1865 (Act VIII of 1865). The remaining portions of the forests were declared a reserve forest the following year and the forest, which was so far administered by the civil administration district, was placed under the control of the Forest Department. A Forest Division, which is the basic forest management and administration unit, was created in 1879 with the headquarters in Khulna, Bangladesh. The first management plan was written for the period 1893–98.[16][17]

In 1911, it was described as a tract of waste country which had never been surveyed nor had the census been extended to it. It then stretched for about 266 kilometres (165 mi) from the mouth of the Hooghly River to the mouth of the Meghna river and was bordered inland by the three settled districts of the 24 Parganas, Khulna and Bakerganj. The total area (including water) was estimated at 16,900 square kilometres (6,526 sq mi). It was a water-logged jungle, in which tigers and other wild beasts abounded. Attempts at reclamation had not been very successful. The Sundarbans were intersected by river channels and creeks, some of which afforded water communication throughout the Bengal region both for steamboats and ships.

Geography

The Sundarban forest lies in the vast delta on the Bay of Bengal formed by the super confluence of the Ganges, Hooghly, Padma, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers across southern Bangladesh. The seasonally flooded Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests lie inland from the mangrove forests on the coastal fringe. The forest covers 10,000 km2 (3,900 sq mi) of which about 6,000 km2 (2,300 sq mi) are in Bangladesh. The Indian part of Sundarbans is estimated to be about 4,110 km2 (1,590 sq mi), of which about 1,700 km2 (660 sq mi) is occupied by water bodies in the forms of river, canals and creeks of width varying from a few metres to several kilometres.

The Sundarbans is intersected by a complex network of tidal waterways, mudflats and small islands of salt-tolerant mangrove forests. The interconnected network of waterways makes almost every corner of the forest accessible by boat. The area is known for the Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris), as well as numerous fauna including species of birds, spotted deer, crocodiles and snakes. The fertile soils of the delta have been subject to intensive human use for centuries, and the ecoregion has been mostly converted to intensive agriculture, with few enclaves of forest remaining. The remaining forests, taken together with the Sundarbans mangroves, are important habitat for the endangered tiger. Additionally, the Sundarbans serves a crucial function as a protective barrier for the millions of inhabitants in and around Khulna and Mongla against the floods that result from the cyclones.

Physiography

The mangrove-dominated Ganges Delta – the Sundarbans – is a complex ecosystem comprising one of the three largest single tracts of mangrove forests of the world. Larger part is situated in Bangladesh, a smaller portion of it lies in India. The Indian part of the forest is estimated to be about 40 percent, while the Bangladeshi part is 60 percent. To the south the forest meets the Bay of Bengal; to the east it is bordered by the Baleswar River and to the north there is a sharp interface with intensively cultivated land. The natural drainage in the upstream areas, other than the main river channels, is everywhere impeded by extensive embankments and polders. The Sundarbans was originally measured (about 200 years ago) to be of about 16,700 square kilometres (6,400 sq mi). Now it has dwindled into about 1/3 of the original size. The total land area today is 4,143 square kilometres (1,600 sq mi), including exposed sandbars with a total area of 42 square kilometres (16 sq mi); the remaining water area of 1,874 square kilometres (724 sq mi) encompasses rivers, small streams and canals. Rivers in the Sundarbans are meeting places of salt water and freshwater. Thus, it is a region of transition between the freshwater of the rivers originating from the Ganges and the saline water of the Bay of Bengal.[18]

The Sundarbans along the Bay of Bengal has evolved over the millennia through natural deposition of upstream sediments accompanied by intertidal segregation. The physiography is dominated by deltaic formations that include innumerable drainage lines associated with surface and subaqueous levees, splays and tidal flats. There are also marginal marshes above mean tide level, tidal sandbars and islands with their networks of tidal channels, subaqueous distal bars and proto-delta clays and silt sediments. The Sundarbans' floor varies from 0.9 to 2.11 metres (3.0 to 6.9 ft) above sea level.[19]

Biotic factors here play a significant role in physical coastal evolution, and for wildlife a variety of habitats have developed which include beaches, estuaries, permanent and semi-permanent swamps, tidal flats, tidal creeks, coastal dunes, back dunes and levees. The mangrove vegetation itself assists in the formation of new landmass and the intertidal vegetation plays a significant role in swamp morphology. The activities of mangrove fauna in the intertidal mudflats develop micromorphological features that trap and hold sediments to create a substratum for mangrove seeds. The morphology and evolution of the eolian dunes is controlled by an abundance of xerophytic and halophytic plants. Creepers, grasses and sedges stabilise sand dunes and uncompacted sediments. The Sunderbans mudflats (Banerjee, 1998) are found at the estuary and on the deltaic islands where low velocity of river and tidal current occurs. The flats are exposed in low tides and submerged in high tides, thus being changed morphologically even in one tidal cycle. The tides are so large that approximately one third of the land disappears and reappears every day.[20] The interior parts of the mudflats serve as a perfect home for mangroves.

Ecoregions

Sundarbans features two ecoregions — "Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests" (IM0162) and "Sundarbans mangroves" (IM1406).[21]

Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests

The Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests are a tropical moist broadleaf forest ecoregion of Bangladesh. It represents the brackish swamp forests that lie behind the Sundarbans Mangroves, where the salinity is more pronounced. The freshwater ecoregion is an area where the water is only slightly brackish and becomes quite fresh during the rainy season, when the freshwater plumes from the Ganges and the Brahmaputra rivers push the intruding salt water out and bring a deposit of silt. It covers 14,600 square kilometres (5,600 sq mi) of the vast Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta, extending from the northern part of Khulna District and finishing at the mouth of the Bay of Bengal with scattered portions extending into India's West Bengal state. The Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests lie between the upland Lower Gangetic plains moist deciduous forests and the brackish-water Sundarbans mangroves bordering the Bay of Bengal.[22]

A victim of large-scale clearing and settlement to support one of the densest human populations in Asia, this ecoregion is under a great threat of extinction. Hundreds of years of habitation and exploitation have exacted a heavy toll on this ecoregion's habitat and biodiversity. There are two protected areas – Narendrapur (110 km2) and Ata Danga Baor (20 km2) that cover a mere 130 km2 of the ecoregion. Habitat loss in this ecoregion is so extensive, and the remaining habitat is so fragmented, that it is difficult to ascertain the composition of the original vegetation of this ecoregion. According to Champion and Seth (1968), the freshwater swamp forests are characterised by Heritiera minor, Xylocarpus molluccensis, Bruguiera conjugata, Sonneratia apetala, Avicennia officinalis, and Sonneratia caseolaris, with Pandanus tectorius, Hibiscus tiliaceus, and Nipa fruticans along the fringing banks.[22]

Sundarbans Mangroves

The Sundarbans Mangroves ecoregion on the coast forms the seaward fringe of the delta and is the world's largest mangrove ecosystem, with 20,400 square kilometres (7,900 sq mi) of an area covered. The dominant mangrove species Heritiera fomes is locally known as sundri or sundari. Mangrove forests are not home to a great variety of plants. They have a thick canopy, and the undergrowth is mostly seedlings of the mangrove trees. Besides the sundari, other tree species in the forest include Avicennia, Xylocarpus mekongensis, Xylocarpus granatum, Sonneratia apetala, Bruguiera gymnorhiza, Ceriops decandra, Aegiceras corniculatum, Rhizophora mucronata, and Nypa fruticans palms.[23] Twenty-six of the fifty broad mangrove species found in the world grow well in the Sundarbans. The commonly identifiable vegetation types in the dense Sundarbans mangrove forests are salt water mixed forest, mangrove scrub, brackish water mixed forest, littoral forest, wet forest and wet alluvial grass forests. The Bangladesh mangrove vegetation of the Sundarbans differs greatly from other non-deltaic coastal mangrove forests and upland forests associations. Unlike the former, the Rhizophoraceae are of minor importance.[24]

Ecological succession

Ecological succession is generally defined as the successive occupation of a site by different plant communities.[25] In an accreting mudflats the outer community along the sequence represents the pioneer community which is gradually replaced by the next community representing the seral stages and finally by a climax community typical of the climatic zone.[26] Robert Scott Troup suggested that succession began in the newly accreted land created by fresh deposits of eroded soil. The pioneer vegetation on these newly accreted sites is Sonneratia, followed by Avicennia and Nypa. As the ground is elevated as a result of soil deposition, other trees make their appearance. The most prevalent, though one of the late species to appear, is Excoecaria. As the level of land rises through accretion and the land is only occasionally flooded by tides, Heritiera fomes begins to appear.[27]

Flora

A total 245 genera and 334 plant species were recorded by David Prain in 1903.[28] While most of the mangroves in other parts of the world are characterised by members of the Rhizophoraceae, Avicenneaceae or Combretaceae, the mangroves of Bangladesh are dominated by the Malvaceae and Euphorbiaceae.[16]

The Sundarbans flora is characterised by the abundance of sundari (Heritiera fomes), gewa (Excoecaria agallocha), goran (Ceriops decandra) and keora (Sonneratia apetala) all of which occur prominently throughout the area. The characteristic tree of the forest is the sundari (Heritiera littoralis), from which the name of the forest had probably been derived. It yields a hard wood, used for building houses and making boats, furniture and other things. New forest accretions is often conspicuously dominated by keora (Sonneratia apetala) and tidal forests. It is an indicator species for newly accreted mudbanks and is an important species for wildlife, especially spotted deer (Axis axis). There is abundance of dhundul or passur (Xylocarpus granatum) and kankra (Bruguiera gymnorhiza) though distribution is discontinuous. Among palms, Poresia coaractata, Myriostachya wightiana and golpata (Nypa fruticans), and among grasses spear grass (Imperata cylindrica) and khagra (Phragmites karka) are well distributed.

The varieties of the forests that exist in Sundarbans include mangrove scrub, littoral forest, saltwater mixed forest, brackish water mixed forest and swamp forest. Besides the forest, there are extensive areas of brackish water and freshwater marshes, intertidal mudflats, sandflats, sand dunes with typical dune vegetation, open grassland on sandy soils and raised areas supporting a variety of terrestrial shrubs and trees. Since Prain's report there have been considerable changes in the status of various mangrove species and taxonomic revision of the man-grove flora.[29] However, very little exploration of the botanical nature of the Sundarbans has been made to keep up with these changes. Differences in vegetation have been explained in terms of freshwater and low salinity influences in the Northeast and variations in drainage and siltation. The Sundarbans has been classified as a moist tropical forest demonstrating a whole mosaic of seres, comprising primary colonisation on new accretions to more mature beach forests. Historically vegetation types have been recognised in broad correlation with varying degrees of water salinity, freshwater flushing and physiography.

Fauna

The Sundarbans provides a unique ecosystem and a rich wildlife habitat. According to the 2015 tiger census in Bangladesh, and the 2011 tiger census in India, the Sundarbans have about 180 tigers (106 in Bangladesh and 74 in India). Earlier estimates, based on counting unique pugmarks, were much higher. The more recent counts have used camera traps, an improved methodology that yields more accurate results.[30][31][32] Tiger attacks are frequent in the Sundarbans, with up to 50 people being killed each year.

Most importantly, mangroves are a transition from the marine to freshwater and terrestrial systems, and provide critical habitat for numerous species of small fish, crabs, shrimps and other crustaceans that adapt to feed and shelter, and reproduce among the tangled mass of roots, known as pneumatophores, which grow upward from the anaerobic mud to get the supply of oxygen. A 1991 study has revealed that the Indian part of the Sundarbans supports diverse biological resources including at least 150 species of commercially important fish, 270 species of birds, 42 species of mammals, 35 reptiles and 8 amphibian species, although new ones are being discovered. This represents a significant proportion of the species present in Bangladesh (i.e. about 30% of the reptiles, 37% the birds and 34% of the mammals) and includes many species which are now extinct elsewhere in the country.[33] Two amphibians, 14 reptiles, 25 aves and five mammals are endangered.[34] The Sundarbans is an important wintering area for migrant water birds[35] and is an area suitable for watching and studying avifauna.[36]

The management of wildlife is restricted to, firstly, the protection of fauna from poaching, and, secondly, designation of some areas as wildlife sanctuaries where no extraction of forest produce is allowed and where the wildlife face few disturbances. Although the fauna of Bangladesh have diminished in recent times[16] and the Sundarbans has not been spared from this decline, the mangrove forest retains several good wildlife habitats and their associated fauna. Of these, the tiger and dolphin are target species for planning wildlife management and tourism development. There are high profile and vulnerable mammals living in two contrasting environments, and their statuses and management are strong indicators of the general condition and management of wildlife. Some species are protected by legislation, notably by the Bangladesh Wildlife (Preservation) Order, 1973 (P.O. 23 of 1973).[37]

Mammals

The Sundarbans are an important habitat for the Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris).[38] The forest also provides habitat for small wild cats such as the jungle cat (Felis chaus), fishing cat (Prionailurus viverrinus), and leopard cat (P. bengalensis).[39]

Several predators dwell in the labyrinth of channels, branches and roots that poke up into the air. This is the only mangrove ecoregion that harbours the Indo-Pacific region's largest terrestrial predator, the Bengal tiger. Unlike in other habitats, tigers live here and swim among the mangrove islands, where they hunt scarce prey such as the chital deer (Axis axis), Indian muntjacs (Muntiacus muntjak), wild boar (Sus scrofa), and Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). It is estimated that there are now 180 Bengal tigers[30] and about 30,000 spotted deer in the area. The tigers regularly attack and kill humans who venture into the forest, human deaths ranging from 30–100 per year.[40]

Avifauna

The forest is also rich in bird life, with 286 species including the endemic brown-winged kingfishers (Pelargopsis amauroptera) and the globally threatened lesser adjutants (Leptoptilos javanicus) and masked finfoots (Heliopais personata) and birds of prey such as the ospreys (Pandion haliaetus), white-bellied sea eagles (Haliaeetus leucogaster) and grey-headed fish eagles (Ichthyophaga ichthyaetus). Some more popular birds found in this region are open billed storks, black-headed ibis, water hens, coots, pheasant-tailed jacanas, pariah kites, brahminy kites, marsh harriers, swamp partridges, red junglefowls, spotted doves, common mynahs, jungle crows, jungle babblers, cotton teals, herring gulls, Caspian terns, gray herons, brahminy ducks, spot-billed pelicans, great egrets, night herons, common snipes, wood sandpipers, green pigeons, rose-ringed parakeets, paradise flycatchers, cormorants, white-bellied sea eagles, seagulls, common kingfishers, peregrine falcons, woodpeckers, Eurasian whimbrels, black-tailed godwits, little stints, eastern knots, curlews, golden plovers, pintails, white-eyed pochards and lesser whistling ducks.

Aquafauna

The Sundarbans National Park is home to olive ridley turtle, hawksbill turtle, green turtle, sea snake, dog-faced water snake, estuarine crocodile, chameleon, king cobra, Russell's viper, house gecko, monitor lizard, pythons, common krait, green vine snake, checkered keelback and rat snake. The river terrapin, Indian flap-shelled turtle (Lissemys punctata), peacock soft-shelled turtle (Trionyx hurum), yellow monitor, Asian water monitor, and Indian python. Fish and amphibians found in the Sundarbans include sawfish, butter fish, electric ray, common carp, silver carp, barb, river eels, starfish, king crab, fiddler crab, hermit crab, prawn, shrimps, Gangetic dolphins, skipper frogs, common toads and tree frogs. One particularly interesting fish is the mudskipper, a gobioid that climbs out of the water into mudflats and even climbs trees.

Endangered and extinct species

Forest inventories reveal a decline in standing volume of the two main commercial mangrove species – sundari (Heritiera spp.) and gewa (Excoecaria agallocha) — by 40% and 45% respectively between 1959 and 1983.[41][42] Despite a total ban on all killing or capture of wildlife other than fish and some invertebrates, it appears that there is a consistent pattern of depleted biodiversity or loss of species (notably at least six mammals and one important reptile) in the 20th century, and that the "ecological quality of the original mangrove forest is declining".[16]

The endangered species that live within the Sundarbans and extinct species that used to be include the royal Bengal tigers, estuarine crocodile, northern river terrapins (Batagur baska), olive ridley sea turtles, Gangetic dolphin, ground turtles, hawksbill sea turtles and king crabs (horse shoe). Some species such as hog deer (Axis porcinus), water buffalos (Bubalus bubalis), barasingha or swamp deer (Cervus duvauceli), Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus), single horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) and the mugger crocodiles or marsh crocodiles (Crocodylus palustris) started to become extinct in the Sundarbans towards the middle of the 20th century, because of extensive poaching and man hunting by the British.[34] There are other threatened mammal species, such as the capped langurs (Semnopithecus pileatus), smooth-coated otters (Lutrogale perspicillata), Oriental small-clawed otters (Aonyx cinerea), and great Bengal civets (Viverra zibetha).

Climate change impact

The physical development processes along the coast are influenced by a multitude of factors, comprising wave motions, micro and macro-tidal cycles and long shore currents typical to the coastal tract. The shore currents vary greatly along with the monsoon. These are also affected by cyclonic action. Erosion and accretion through these forces maintains varying levels, as yet not properly measured, of physiographic change whilst the mangrove vegetation itself provides a remarkable stability to the entire system. During each monsoon season almost all the Bengal Delta is submerged, much of it for half a year. The sediment of the lower delta plain is primarily advected inland by monsoonal coastal setup and cyclonic events. One of the greatest challenges people living on the Ganges Delta may face in coming years is the threat of rising sea levels caused mostly by subsidence in the region and partly by climate change.

In many of the Bangladesh's mangrove wetlands, freshwater reaching the mangroves was considerably reduced from the 1970s because of diversion of freshwater in the upstream area by neighbouring India through the use of the Farakka Barrage bordering Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Also, the Bengal Basin is slowly tilting towards the east because of neo-tectonic movement, forcing greater freshwater input to the Bangladesh Sundarbans. As a result, the salinity of the Bangladesh Sundarbans is much lower than that of the Indian side. A 1990 study noted that there "is no evidence that environmental degradation in the Himalayas or a 'greenhouse' induced rise in sea level have aggravated floods in Bangladesh"; however, a 2007 report by UNESCO, "Case Studies on Climate Change and World Heritage" has stated that an anthropogenic 45-centimetre (18 in) rise in sea level (likely by the end of the 21st century, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), combined with other forms of anthropogenic stress on the Sundarbans, could lead to the destruction of 75 percent of the Sundarbans mangroves.[43] Already, Lohachara Island and New Moore Island/South Talpatti Island have disappeared under the sea, and Ghoramara Island is half submerged.[44]

In a study conducted in 2012, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) found out that the Sunderban coast was retreating up to 200 metres (660 ft) in a year. Agricultural activities had destroyed around 17,179 hectares (42,450 acres) of mangroves within three decades (1975–2010). Shrimp cultivation had destroyed another 7,554 hectares (18,670 acres).

Researches from the School of Oceanographic Studies, Jadavpur University, estimated the annual rise in sea level to be 8 millimetres (0.31 in) in 2010. It had doubled from 3.14 millimetres (0.124 in) recorded in 2000. The rising sea levels had also submerged around 7,500 hectares (19,000 acres) of forest areas. This, coupled with an around 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) rise in surface water temperatures and increased levels of salinity have posed a problem for the survival of the indigenous flora and fauna. The Sundari trees are exceptionally sensitive to salinity and are being threatened with extinction.

Loss of the mangrove forest will result in the loss of the protective biological shield against cyclones and tsunamis. This may put the surrounding coastal communities at high risk. Moreover, the submergence of land mass have rendered up to 6,000 families homeless and around 70,000 people are immediately threatened with the same.[45][46][47] This is causing the flight of human capital to the mainland, about 13% in the decade of 2000–2010.[48]

A 2015 ethnographic study, conducted by a team of researchers from Heiderberg university in Germany, found a crisis brewing in the Sunderbans. The study contended that poor planning on the part of the India and Bangladesh governments coupled with natural ecological changes were forcing the flight of human capital from the region [48][49]

Hazards

Natural hazards

According to a report created by UNESCO, the landfall of Cyclone Sidr damaged around 40% of Sundarbans in 2007.[50]

Man made hazards

In August 2010, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB) and India's state-owned National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) where they designated to implement the coal-fired Rampal power station by 2016.[51][52] The proposed project, on an area of over 1,834 acres of land, is situated 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) north of the Sundarbans.[53] This project violates the environmental impact assessment guidelines for coal-based thermal power plants.[54] Environmental activists contend that the proposed location of the Rampal Station would violate provisions of the Ramsar Convention.[55][56] The government of Bangladesh rejected the allegations that the coal-based power plant would adversely affect the world's largest mangrove forest.[57]

On 9 December 2014 an oil-tanker named Southern Star VII,[58] carrying 358,000 litres (79,000 imp gal; 95,000 US gal) of furnace oil,[59][60] was sunk in the Sela river[61] of Sundarbans after it had been hit by a cargo vessel.[58][60] The oil spread over 350 km2 (140 sq mi) area after the clash, as of 17 December.[62] The slick spread to a second river and a network of canals in the Sundarbans and blackened the shoreline.[63] The event was very threatening to trees, plankton, vast populations of small fishes and dolphins.[64] The event occurred at a protected Sundarbans mangrove area, home to rare Irrawaddy and Ganges dolphins.[65] Until 15 December 2014 only 50,000 litres (11,000 imp gal; 13,000 US gal) of oil from the area were cleaned up by local residents, Bangladesh Navy and the government of Bangladesh.[59][66] Some reports indicated that the event killed some wildlife.[61] On 13 December 2014, a dead Irrawaddy dolphin was seen floating on the Harintana-Tembulbunia channel of the Sela River.[67]

Economy

The Sundarbans plays an important role in the economy of the southwestern region of Bangladesh as well as in the national economy. It is the single largest source of forest produce in the country. The forest provides raw materials for wood-based industries. In addition to traditional forest produce like timber, fuelwood, pulpwood etc., large-scale harvest of non-wood forest products such as thatching materials, honey, beeswax, fish, crustacean and mollusc resources of the forest takes place regularly. The vegetated tidal lands of the Sundarbans function as an essential habitat, produces nutrients and purifies water. The forest also traps nutrient and sediment, acts as a storm barrier, shore stabiliser and energy storage unit. Last but not the least, the Sunderbans provides an aesthetic attraction for local and foreign tourists.

The forest has immense protective and productive functions. Constituting 51% of the total reserved forest estate of Bangladesh, it contributes about 41% of total forest revenue and accounts for about 45% of all timber and fuel wood output of the country.[68] A number of industries (e.g., newsprint mill, match factory, hardboard, boat building, furniture making) are based on raw materials obtained from the Sundarbans ecosystem. Non-timber forest products and plantations help generate considerable employment and income opportunities for at least half a million poor coastal people. It provides natural protection to life and properties of the coastal population in cyclone-prone Bangladesh.

Agriculture

Part of the Sundarbans is shielded from tidal inflow by leaves and there one finds villages and agriculture. During the monsoon season, the low lying agricultural lands are waterlogged and the summer crop (kharif crop) is therefore mainly deepwater rice or floating rice. In the dry winter season the land is normally uncropped and used for cattle grazing. However, the lands near the villages are irrigated from ponds that were filled up during monsoon, and vegetable crops (Rabi crops) can be grown here.[69]

Habitation

The Sundarbans has a population of over 4 million[70] but much of it is mostly free of permanent human habitation. Despite human habitations and a century of economic exploitation of the forest well into the late 1940s, the Sundarbans retained a forest closure of about 70% according to the Overseas Development Administration (ODA) of the United Kingdom in 1979.

Administration

The Sundarbans area is one of the most densely populated areas in the world, and the population is increasing. As a result, half of this ecoregion's mangrove forests have been cut down to supply fuelwood and other natural resources. Despite the intense and large-scale exploitation, this still is one of the largest contiguous areas of mangroves in the world. Another threat comes from deforestation and water diversion from the rivers inland, which causes far more silt to be brought to the estuary, clogging up the waterways.

The Directorate of Forest is responsible for the administration and management of Sundarban National Park in West Bengal. The Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (PCCF), Wildlife & Bio-Diversity & ex-officio Chief Wildlife Warden, West Bengal is the senior most executive officer looking over the administration of the park. The Chief Conservator of Forests (South) & Director, Sundarban Biosphere Reserve is the administrative head of the park at the local level and is assisted by a Deputy Field Director and an Assistant Field Director. The park area is divided into two ranges, overseen by range forest officers. Each range is further sub-divided into beats. The park also has floating watch stations and camps to protect the property from poachers.

The park receives financial aid from the State Government as well as the Ministry of Environment and Forests under various Plan and Non-Plan Budgets. Additional funding is received under the Project Tiger from the Central Government. In 2001, a grant of US$20,000 was received as a preparatory assistance for promotion between India and Bangladesh from the World Heritage Fund.

A new Khulna Forest Circle was created in Bangladesh back in 1993 to preserve the forest, and Chief Conservators of Forests have been posted since. The direct administrative head of the Division is the Divisional Forest Officer, based at Khulna, who has a number of professional, subprofessional and support staff and logistic supports for the implementation of necessary management and administrative activities. The basic unit of management is the compartment. There are 55 compartments in four Forest Ranges and these are clearly demarcated mainly by natural features such as rivers, canals and creeks.

Protected areas

The Bangladesh part of the forest lies under two forest divisions, and four administrative ranges viz Chandpai (Khulna District), Sarankhola (Khulna), and Burigoalini (Satkhira District) and has sixteen forest stations. It is further divided into fifty-five compartments and nine blocks.[12] There are three wildlife sanctuaries established in 1977 under the Bangladesh Wildlife (Preservation) Order, 1973 (P.O. 23 of 1973). The West Bengal part of the forest lies under the district of South & North 24 Parganas.

Protected areas cover 15% of the Sundarbans mangroves including Sundarbans National Park and Sajnakhali Wildlife Sanctuary, in West Bengal, Sundarbans East, Sundarbans South and Sundarbans West Wildlife Sanctuaries in Bangladesh.[23]

In May 2019, the local authorities in Bangladesh killed 4 tiger poachers in a shootout in the Sunderbans mangrove area where currently 114 tigers dwell.

Sundarban National Park

The Sundarban National Park is a National Park, Tiger Reserve, and a Biosphere Reserve in West Bengal, India. It is part of the Sundarbans on the Ganges Delta, and adjacent to the Sundarbans Reserve Forest in Bangladesh. The delta is densely covered by mangrove forests, and is one of the largest reserves for the Bengal tiger. It is also home to a variety of bird, reptile and invertebrate species, including the salt-water crocodile. The present Sundarbans National Park was declared as the core area of Sundarbans Tiger Reserve in 1973 and a wildlife sanctuary in 1977. On 4 May 1984 it was declared a National Park.

Sundarbans West Wildlife Sanctuary

Sundarbans West Wildlife Sanctuary is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The region supports mangroves, including: sparse stands of Gewa (Excoecaria agallocha) and dense stands of Goran (Ceriops tagal), with discontinuous patches of Hantal palm (Phoenix paludosa) on drier ground, river banks and levees. The fauna of the sanctuary is very diverse with some 40 species of mammals, 260 species of birds and 35 species of reptiles. The greatest of these being the Bengal tiger of which an estimated 350 remain in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Other large mammals are wild boar, chital horin (spotted deer), Indian otter and macaque monkey. Five species of marine turtles frequent the coastal zone and two endangered reptiles are present – the estuarine crocodile and the Indian python.[71]

Sundarbans East Wildlife Sanctuary

Sundarbans East Wildlife Sanctuary extends over an area of 31,227 hectares (77,160 acres). Sundari trees (Heritiera fomes) dominate the flora, interspersed with Gewa (Excoecaria agallocha) and Passur (Xylocarpus mekongensis) with Kankra (Bruguiera gymnorhiza) occurring in areas subject to more frequent flooding. There is an understory of Shingra (Cynometra ramiflora) where, soils are drier and Amur (Aglaia cucullata) in wetter areas and Goran (Ceriops decandra) in more saline places. Nypa palm (Nypa fruticans) is widespread along drainage lines.

Sundarbans South Wildlife Sanctuary

Sundarbans South Wildlife Sanctuary extends over an area of 36,970 hectares (91,400 acres). There is evidently the greatest seasonal variation in salinity levels and possibly represents an area of relatively longer duration of moderate salinity where Gewa (Excoecaria agallocha) is the dominant woody species. It is often mixed with Sundri, which is able to displace in circumstances such as artificially opened canopies where Sundri does not regenerate as effectively. It is also frequently associated with a dense understory of Goran (Ceriops tagal) and sometimes Passur.

Sajnakhali Wildlife Sanctuary

Sajnakhali Wildlife Sanctuary is a 362-square-kilometre (140 sq mi) area in the northern part of the Sundarbans delta in South 24 Parganas district, West Bengal, India. It is mainly mangrove scrub, forest and swamp. It was set up as a sanctuary in 1976. It is home to a rich population of different species of wildlife, such as water fowl, heron, pelican, spotted deer, rhesus macaques, wild boar, tigers, water monitor lizards, fishing cats, otters, olive ridley turtles, crocodiles, batagur terrapins, and migratory birds.

In popular culture

The Sundarbans is celebrated through numerous Bengali folk songs and dances, often centred around the folk heroes, gods and goddesses specific to the Sunderbans (like Bonbibi and Dakshin Rai) and to the Lower Gangetic Delta (like Manasa and Chand Sadagar). The Bengali folk epic Manasamangal mentions Netidhopani and has some passages set in the Sundarbans during the heroine Behula's quest to bring her husband Lakhindar back to life.

The area provides the setting for several novels by Emilio Salgari, (e.g. The Mystery of the Black Jungle). Sundarbaney Arjan Sardar, a novel by Shibshankar Mitra, and Padma Nadir Majhi, a novel by Manik Bandopadhyay, are based on the rigors of lives of villagers and fishermen living in the Sunderbans region, and are woven into the Bengali psyche to a great extent. Part of the plot of Salman Rushdie's Booker Prize winning novel, Midnight's Children is set in the Sundarbans. This forest is adopted as the setting of Kunal Basu's short story "The Japanese Wife" and the subsequent film adaptation. Most of the plot of an internationally acclaimed novelist, Amitav Ghosh's 2004 novel, The Hungry Tide, is set in the Sundarbans. The plot centres on a headstrong American cetologist who arrives to study a rare species of river dolphin, enlisting a local fisherman and translator to aid her. The book also mentions two accounts of the Bonbibi story of "Dukhey's Redemption".[72] Manik Bandopadhyay's Padma Nadir Majhi was made into a movie by Goutam Ghose.

The Sunderbans has been the subject of a detailed and well-researched scholarly work on Bonbibi (a 'forest goddess' venerated by Hindus), on the relation between the islanders and tigers and on conservation and how it is perceived by the inhabitants of the Sundarbans,[73] as well as numerous non-fiction books, including The Man-Eating Tigers of Sundarbans by Sy Montegomery for a young audience, which was shortlisted for the Dorothy Canfield Fisher Children's Book Award. In Up The Country, Emily Eden discusses her travels through the Sunderbans.[74] Numerous documentary movies have been made about the Sunderbans, including the 2003 IMAX production Shining Bright about the Bengal tiger. The acclaimed BBC TV series Ganges documents the lives of villagers, especially honey collectors, in the Sundarbans.

See also

References

- "Sundarbans Reserved Forest, Bangladesh". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- "Sundarban Wetland, India". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Giri, C.; Pengra, B.; Zhu, Z.; Singh, A.; Tieszen, L. L. (2007). "Monitoring mangrove forest dynamics of the Sundarbans in Bangladesh and India using multi-temporal satellite data from 1973 to 2000". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 73 (1−2): 91−100. Bibcode:2007ECSS...73...91G. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2006.12.019.

- Pani, D. R.; Sarangi, S. K.; Subudhi, H. N.; Misra, R. C.; Bhandari, D. C. (2013). "Exploration, evaluation and conservation of salt tolerant rice genetic resources from Sundarbans region of West Bengal" (PDF). Journal of the Indian Society of Coastal Agricultural Research. 30 (1): 45–53.

- Iftekhar, M. S.; Islam, M. R. (2004). "Managing mangroves in Bangladesh: A strategy analysis" (PDF). Journal of Coastal Conservation. 10 (1): 139–146. doi:10.1652/1400-0350(2004)010[0139:MMIBAS]2.0.CO;2.

- Manna, S.; Chaudhuri, K.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Bhattacharyya, M. (2010). "Dynamics of Sundarban estuarine ecosystem: Eutrophication induced threat to mangroves". Saline Systems. 6: 8. doi:10.1186/1746-1448-6-8. PMC 2928246. PMID 20699005.

- "23 dead, 1 lakh affected as Cyclone Aila hits Bengal". The Times of India.

- "Cyclone Aila". 2009.

- Iftekhar Mahmud (2016). "Unesco calls for shelving Rampal project". Prothom Alo. Archived from the original on 26 September 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Biswas, S. (2000). "সুন্দর". Samsad Bengali-English dictionary. Calcutta: Sahitya Samsad. p. 1017.

- Biswas, S. (2000). "বন". Samsad Bengali-English dictionary. Calcutta: Sahitya Samsad. p. 717.

- Siddiqui, N. A. (2012). "Sundarbans, The". In Islam, S.; Jamal, A. A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- "Sunderban Mangroves". Geological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 10 December 2009. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- "Sunderbans" (PDF). Protected areas and World Heritage sites. United Nations Environmental Programme. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- Laskar Muqsudur, Rahman. "The Sundarbans: A Unique Wilderness of the World" (PDF). Wilderness.net. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- Hussain, Z.; Acharya, G., eds. (1994). Mangroves of the Sundarbans. Volume 2, Bangladesh. Bangkok: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. OCLC 773534471.

- UNDP (1998). Integrated resource development of the Sundarbans Reserved Forests, Bangladesh. Volume I Project BGD/84/056, United Nations Development Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Dhaka, The People's Republic of Bangladesh.

- Wahid, S.M.; Alam, M.J. & Rahman, A. (2002). Mathematical river modelling to support ecological monitoring of the largest mangrove forest of the world – the Sundarbans. Proceedings of First Asia-Pacific DHI software conference, 17–18 June 2002.

- Katebi, M.N.A. and Habib, M.G. (1987). Sundarbans and Forestry in Coastal Area Resource Development and Management Part II, BRAC Printers, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Shapiro, Ari (20 May 2016). "Rising Tides Force Thousands To Leave Islands Of Eastern India". NPR. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Ecoregions: Indo-Malayan Archived 28 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine, World Wildlife Fund

- "Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- "Sundarbans Mangroves". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Rahman, MR; Asaduzzaman, M (16 April 2013). "Ecology of Sundarban, Bangladesh". Journal of Science Foundation. 8 (1–2): 35–47. doi:10.3329/jsf.v8i1-2.14618. ISSN 1728-7855.

- Weaver, J. E.; Clements, F. E. (1938). Plant Ecology (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill Book Company. OCLC 502944133.

- Watson, J.G. (1928). "Mangrove swamps of the Malayan peninsula". Malayan Forest Records. 6: 1–275.

- Troup, R. S. (1921). The Silviculture of Indian Trees. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 155.

On newly formed islands, flooded by every tide, Sonneratia usually springs up first, followed by Avicennia and the palm Nipa fruticans. As the ground rises other trees make their appearance, the most prevalent, though one of the later species to appear, being Exaecaria Agallocha. As the level rises by accretion, and the land is only occasionally flooded by the tide, the sundri makes its appearance.

- Prain, David (1903). "Flora of the Sundribuns". Records of the Botanical Survey of India. Volume II. Calcutta: Allied Book Centre. p. 251.

- Khatun, B.M.R.; Hafiz, Syed (1987). "Taxonomic studies in the genus Avicennia L. from Bangladesh". Bangladesh J. Bot. 16 (1): 39–44.

- "Only 100 tigers left in Bangladesh's famed Sundarbans forest". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 27 July 2015.

- "India wild tiger census shows population rise". BBC News. 28 March 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- "Joint Tiger census-2004 in Sundarban Reserved Forests". Bangladesh Forest Department. Ministry of Environment and Forest. Archived from the original on 7 December 2004. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Scott, D. A. (1991). "Asia and the Middle East in". In Finlayson, C. M.; Moser, M. (eds.). Wetlands. Oxford. pp. 151–178. ISBN 978-0-8160-2556-5.

- Sarker, S.U. 1993. Ecology of Wildlife UNDP/FAO/BGD/85/011. Field Document N. 50 Institute of Forestry and Environmental Sciences. Chittagong, Bangladesh.

- Zöckler, C.; Balachandran, S.; Bunting, G.C.; Fanck, M.; Kashiwagi, M.; Lappo, E.G.; Maheswaran, G.; Sharma, A.; Syroechkovski, E.E.; Webb, K. (2005). "The Indian Sunderbans: an important wintering site for Siberian waders" (PDF). Wader Study Group Bulletin. 108: 42–46.

- Habib, M.G. (1999). Message In: Nuruzzaman, M., I.U. Ahmed and H. Banik (eds.). The Sundarbans world heritage site: an introduction, Forest Department, Ministry of Environment and Forest, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh.

- THE ORIGINAL BANGLADESH WILDLIFE PRESERVATION ORDER 1973 THE DRAFT. nishorgo.org

- Khan, M. M. H. (2004). Ecology and conservation of the Bengal tiger in the Sundarbans Mangrove forest of Bangladesh (PDF) (PhD thesis). Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

- Khan, M. M. H. (2004). "Food habit of the Leopard Cat Prionailurus bengalensis (Kerr, 1792) in the Sundarbans East Wildlife Sanctuary, Bangladesh". Zoos' Print Journal. 19 (5): 1475−1476. doi:10.11609/JoTT.ZPJ.1101.1475-6.

- Goodrich, J.; Lynam, A.; Miquelle, D.; Wibisono, H.; Kawanishi, K.; Pattanavibool, A.; Htun, S.; Tempa, T.; Karki, J.; Jhala, Y.; Karanth, U. (2015). "Panthera tigris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T15955A50659951.

- Forestal (1960). Forest Inventory 1958–59 Sundarbans Forests (Report). Oregon, Canada: Forestal Forestry and Engineering International Ltd.

- Chaffey, D. R.; Miller, F. R. & Sandom, J. H. (1985). A forest inventory of the Sundarbans, Bangladesh (Report). Surbiton, England: Land Resources Development Centre.

- Case Studies of Climate Change, UNESCO, 2007

- George, Nirmala (24 March 2010). "Disputed isle in Bay of Bengal disappears into sea". Yahoo News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- "Mangrove forests threatened by Climate Change in the Sundarbans of Bangladesh and India". 12 January 2013.

- "Global Warming: Rising Seas creates 70,000 Climate Refugees". 27 December 2006.

- Cornforth, William A.; Fatoyinbo, Temilola E.; Freemantle, Terri P.; Pettorelli, Nathalie (2013). "Advanced Land Observing Satellite Phased Array Type L-Band SAR (ALOS PALSAR) to Inform the Conservation of Mangroves: Sundarbans as a Case Study". Remote Sensing. 5 (1): 224–237. Bibcode:2013RemS....5..224C. doi:10.3390/rs5010224.

- Foundation, Thomson. "'Everyday disasters' driving flight from Sundarbans". trust.org. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Foundation, Thomson. "Poor planning, climate shifts devastating India's Sundarbans". trust.org. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- "Cyclone Sidr damaged 40% of Sundarbans: UNESCO". ibnlive.in. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- New Age | Newspaper

- Final report on environmental impact assessment of 2x (500-660) MW coal-based thermal power plant to be constructed at the location of Khulna - India Environment Portal

- Rahman, Khalilur (24 February 2013). "Demand for Rampal power plant relocation". The Financial Express. Dhaka.

- Kumar, Chaitanya (24 September 2013). "Bangladesh Power Plant Struggle Calls for International Solidarity". The World Post.

- "The Roar of Disapproval". Dhaka Courier. 29 September 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- "Rampal plant won't hamper environ". The New Nation. 27 October 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Habib, Haroon (27 September 2013). "Bangladesh begins import of power from India". The Hindu.

- Krishnendu Mukherjee, Rakhi Chakrabarty. "350-tonne oil spill by Bangladeshi ship threatens Sunderbans". The Times of India. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "India on alert after Sunderbans oil spill in Bangladesh". BBC News. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- Phillips, Tom (13 December 2014). "Fears for rare wildlife as oil 'catastrophe' strikes Bangladesh". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "Massive Oil Spill Threatens Bangladesh's Sundarbans". Global Voices Online. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "Assessing the oil spill's impact on Bangladesh's Sundarbans forest". Deutsche Welle. 17 December 2014.

- "Bangladesh launches campaign to clean up Sunderbans oil spill". The Hindu. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "Bangladesh begins oil clean-up after spill". Al Jazeera. 12 December 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "Bangladesh oil spill threatens rare dolphins". Al Jazeera. 11 December 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "No capacity to tackle oil spills". The Daily Star. 16 December 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- Siddique, Abu Bakar (14 December 2014). "First dead dolphin spotted". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- Integrated Resource Management Plan of the Sundarbans Reserved Forest, FAO Project BGD/84/056 (Report). Rome, Italy: FAO. 1995.

- H.S.Sen, 1992. Research on water management in the Sundarbans, West Bengal, India. Published in the Annual Report 1992 of the International Institute for Land Reclamation and improvement, Wageningen, the Netherlands. On line:

- Subir Bhaumik (15 September 2003). "Fears rise for sinking Sundarbans". BBC News.

- UNESCO World Heritage Nomination, 1997

- Ghosh, Amitav (2005). The Hungry Tide: A Novel., Boston: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 84–88, 292–97 ISBN 0-14-301556-7.

- Jalais, Annu. (2010). Forest of Tigers: People, Politics and Environment in the Sundarbans, Routledge: New Delhi, London, New York, ISBN 0-415-69046-3.

- Eden, Emily (1867). 'Up the country': letters written to her sister from the upper provinces of India. R. Bentley.

Sources

- Laskar Muqsudur Rahman, The Sundarbans: A Unique Wilderness of the World; at USDA Forest Reserve; McCool, Stephen F.; Cole, David N.; Borrie, William T.; O'Loughlin, Jennifer, comps. 2000. Wilderness science in a time of change conference, Volume 2: Wilderness within the context of larger systems; 1999 May 23–27; Missoula, MT. Proceedings RMRS-P-15-VOL-2. Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

- Terminal Report, Integrated Resource Development of the Sundarbans Reserved Forest: Project Findings and Recommendations, Food and Agriculture Organization (acting as executing agency for the United Nations Development Programme), United Nations, Rome, 1998 (prepared for the Government of Bangladesh)

- Blasco, F. (1975). The Mangroves of India. Institut Francis de Pondichéry, Travaux de las Section Scientifique et Technique, Tome XIV, Facicule 1. Pondicherry, India.

- Jalais, Annu. (2005). "Dwelling on Morichjhanpi: When Tigers Became 'Citizens', Refugees 'Tiger-Food'"; Economic and Political Weekly, 23 April 2005, pp. 1757 – 1762.

- Jalais, Annu. (2007). "The Sundarbans: Whose World Heritage Site?", Conservation and Society (vol. 5, no. 4).

- Jalais, Annu. (2008). "Unmasking the Cosmopolitan Tiger", Nature and Culture (vol. 3, no. 1), pp. 25–40.

- Jalais, Annu. (2008). "Bonbibi: Bridging Worlds", Indian Folklore, serial no. 28, Jan 2008.

- Jalais, Annu. (2009). "Confronting Authority, Negotiating Morality: tiger prawn seed collection in the Sundarbans", International Collective in Support of Fishworkers, Yemaya, 32, Nov. ; Also in French: http://base.d-p-h.info/en/fiches/dph/fiche-dph-8148.html

- Jalais, Annu. (2010). "Braving Crocodiles with Kali: Being a prawn-seed collector and a modern woman in the 21st century Sundarbans", Socio-Legal Review, Vol. 6.

- Montgomery, Sy (1995). Spell of the Tiger: The Man-Eaters of Sundarbans. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York.

- Rivers of Life: Living with Floods in Bangladesh. M. Q. Zaman. Asian Survey, Vol. 33, No. 10 (October 1993), pp. 985–996

- Allison, M. A.; Kepple, E. B. (September 2001). "Modern sediment supply to the lower delta plain of the Ganges-Brahmaputra River in Bangladesh". Geo-Marine Letters. 21 (2): 66. Bibcode:2001GML....21...66M. doi:10.1007/s003670100069.

- Sundarbans on United Nations Environment Programme

- Brammer, H. (July 1990). "Floods in Bangladesh: II. Flood Mitigation and Environmental Aspects". The Geographical Journal. 156 (2): 158–165. doi:10.2307/635323. JSTOR 635323.

- Environmental classification of mangrove wetlands of India. V. Selvam. Current Science, Vol. 84, No. 6, 25 March 2003.

- Green, M.J.B.; Centre, W.C.M.; Parks, I.C.o.N.; Areas, P. (1990). Iucn Directory of South Asian Protected Areas. IUCN-The World Conservation Union. ISBN 978-2-8317-0030-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sundarbans. |

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre: The Sundarbans

- UNESCO: Sundarban Biosphere Reserve Information

- World Heritage Site: The Sundarbans

- United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre Protected Areas Programme: The Sundarbans

- The Sundarban of Bangladesh: A Rich Biodiversity of the World's Largest Mangrove Ecosystem

- Greenpeace: Sinking Sundarbans – Climate voices

- Tiger Conservation Project in the Bangladeshi Sundarbans

- Research on water management and control in the Sunderbans, West Bengal, India

- Finfishes of Sundarbans

- Nasa images: set 01 and set 2

- Bong Blogger: Sundarban Tour with SHER

- Travel Mate: Largest Mangrove Forest

.jpg)