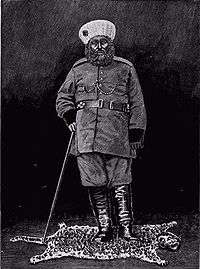

Abdur Rahman Khan

Abdur Rahman Khan (Pashto: عبدالرحمان خان) (between 1840 and 1844 – October 1, 1901) was Emir of Afghanistan from 1880 to 1901.[1] He is known for uniting the country after years of internal fighting and negotiation of the Durand Line Agreement with British India.[2]

| Abdul Rahman Khan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emir of Afghanistan | |||||

Abdur Rahman Khan | |||||

| Emir of Afghanistan | |||||

| Reign | 31 May 1880 – 1 October 1901 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ayub Khan | ||||

| Successor | Habibullah Khan | ||||

| Born | 1840–1844 Kabul, Afghanistan | ||||

| Died | 1 October 1901 (aged c.56-61) Kabul, now Afghanistan | ||||

| Burial | 1901 Kabul, Afghanistan | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Barakzai dynasty | ||||

| Father | Mohammad Afzal Khan | ||||

Abdur Rahman Khan was the first child and only son of Mohammad Afzal Khan, and grandson of Dost Mohammad Khan. Abdur Rahman Khan re-established the writ of the Afghan government after the disarray that followed the second Anglo-Afghan war.

He became known as The Iron Amir because his government was a military despotism resting upon a well-appointed army administered through officials absolutely subservient to an inflexible will and controlled by a widespread system of espionage;[3] and for his crushing of a number of rebellions by various tribes who were led by his relatives.[4]

Background and early career

Before his death in Herat, on June 9, 1863, Abdur Rahman's grandfather, Dost Mohammad Khan, nominated his third son, Sher Ali Khan, as his successor, passing over the two elder brothers, Afzal Khan and Azam Khan. At first, the new Amir was quietly recognized. But after a few months, Afzal Khan raised an insurrection in the north of the country, where he had been governing when his father died. This began a fierce internecine conflict for power between Dost Mohammad's sons, which lasted for nearly five years.[5] The Musahiban are descendants of Dost Mohammad Khan's older brother, Sultan Mohammad Khan.[6]

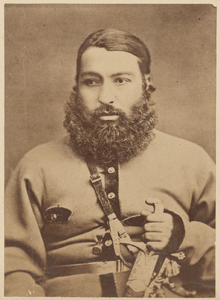

Described by the American scholar and explorer Eugene Schuyler as "a tall well-built man, with a large head, and a marked Afghan, almost Jewish, face",[7] Abdur Rahman distinguished himself for his ability and energetic daring. Although his father, Afzal Khan came to terms with the Amir Sher Ali, Abdur's behaviour in the northern province soon excited the Amir's suspicion and, when he was summoned to Kabul, fled across the Oxus into Bukhara. Sher Ali threw Afzal Khan into prison, and a revolt followed in southern Afghanistan.[5]

The Amir had scarcely suppressed it by winning a desperate battle when Abdur Rahman's reappearance in the north was a signal for a mutiny by troops stationed in those parts and a gathering of armed bands to his standard. After some delay and desultory fighting, he and his uncle, Azam Khan, occupied Kabul in March 1866. The Amir Sher Ali marched up against them from Kandahar; but in the battle that ensued at Sheikhabad on May 10, he was deserted by a large body of his troops, and after his signal defeat Abdur Rahman released his father, Afzal Khan, from prison in Ghazni, and installed him upon the throne as Amir of Afghanistan. Notwithstanding the new Amir's incapacity, and some jealousy between the real leaders, Abdur Rahman and his uncle, they again routed Sher Ali's forces, and occupied Kandahar in 1867. When Afzal Khan died at the end of the year, Azam Khan became the new ruler, with Abdur Rahman installed as governor in the northern province. But towards the end of 1868, Sher Ali's return and a general rising in his favour resulted in Abdur Rahman and Azam Khan's defeat at Tinah Khan on January 3, 1869. Both sought refuge to the east in Central Asia, where Abdur Rahman placed himself under Russian protection at Samarkand.[8] Azam died in Kabul in October 1869.[5]

Exile and negotiated return to power

Abdur Rahman lived in exile in Tashkent. He was being told to cross the Oxus and claim throne for Amir.[5][8] In March 1880, a report reached India that Abdur Rahman was in northern Afghanistan; and the Governor-General, Lord Lytton, opened communications with him to the effect that the British government were prepared to withdraw their troops, and to recognize Abdur Rahman as Amir of Afghanistan, with the exception of Kandahar and some districts adjacent to it. After some negotiations, and an interview with Lepel Griffin, the diplomatic representative at Kabul of the Indian government. Griffin described Abdur Rahman as a man of middle height, with an exceedingly intelligent face and frank and courteous manners, shrewd and able in conversation on the business in hand.[5]

Reign

At the durbar on July 22, 1880, Abdur Rahman was officially recognized as Amir, granted assistance in arms and money, and promised, in case of unprovoked foreign aggression, such further aid as might be necessary to repel it, provided that he align his foreign policy with the British. The British evacuation of Afghanistan was settled on the terms proposed, and in 1881, the British troops also handed over Kandahar to the new Amir.[5]

However, Ayub Khan, one of Sher Ali Khan's sons, marched upon that city from Herat, defeated Abdur Rahman's troops, and occupied the place in July 1880. This serious reverse roused the Amir, who had not displayed much activity. Instead, Ayub Khan was defeated in Kandahar by the British General Frederick Roberts on 1 September 1880. Ayub Khan was forced to flee into Persia. From that time Abdur Rahman was fairly seated firm on the throne at Kabul, thanks to the unwavering British protections in terms of giving large supplies of arms and money. In the course of the next few years, Abdul Rahman consolidated his grip over all Afghanistan, suppressing insurrection by a relentless and brutal use of his despotic authority. The powerful Ghilzai revolted against the severity of his measures several times. In that same year, Ayub Khan made a fruitless inroad from Persia.

In 1885, at the moment when the Amir was in conference with the British viceroy, Lord Dufferin, in India, the news came of a skirmish between Russian and Afghan troops at Panjdeh, over a disputed point in the demarcation of the northwestern frontier of Afghanistan. Abdur Rahman's attitude at this critical juncture is a good example of his political sagacity. To one who had been a man of war from his youth, who had won and lost many fights, the rout of a detachment and the forcible seizure of some debatable frontier lands was an untoward incident; but it was not a sufficient reason for calling upon the British, although they had guaranteed his territory's integrity, to vindicate his rights by hostilities which would certainly bring upon him a Russian invasion from the north, and would compel his British allies to throw an army into Afghanistan from the southeast.[9] He also published his autobiography in 1885, which served more as an advice guide for princes than anything else.[10]

His interest lay in keeping powerful neighbours, whether friends or foes, outside his kingdom. He knew this to be the only policy that would be supported by the Afghan nation; and although for some time a rupture with Russia seemed imminent, while the Government of India made ready for that contingency, the Amir's reserved and circumspect tone in the consultations with him helped to turn the balance between peace and war, and substantially conduced towards a pacific solution. Abdur Rahman left on those who met him in India the impression of a clear-headed man of action, with great self-reliance and hardihood, not without indications of the implacable severity that too often marked his administration. His investment with the insignia of the highest grade of the Order of the Star of India appeared to give him much pleasure.[3]

His adventurous life, his forcible character, the position of his state as a barrier between the Indian and the Russian empires, and the skill with which he held the balance in dealing with them, combined to make him a prominent figure in contemporary Asian politics and will mark his reign as an epoch in the history of Afghanistan. The Amir received an annual subsidy from the British government of 1,850,000 rupees. He was allowed to import munitions of war.[3] He succeeded in imposing an organized government upon the fiercest and most unruly population in Asia; he availed himself of European inventions for strengthening his armament, while he sternly set his face against all innovations which, like railways and telegraphs, might give Europeans a foothold within his country.[3]

In 1893 he built himself a summer house called the Bagh-e Bala Palace.

The Amir found himself unable, by reason of ill-health, to accept an invitation from Queen Victoria to visit England; but his second son Nasrullah Khan went instead.[3]

Durand Line

In 1893, Mortimer Durand was deputed to Kabul by the government of British India for this purpose of settling an exchange of territory required by the demarcation of the boundary between northeastern Afghanistan and the Russian possessions, and in order to discuss with Amir Abdur Rahman Khan other pending questions. Abdur Rahman Khan showed his usual ability in diplomatic argument, his tenacity where his own views or claims were in debate, with a sure underlying insight into the real situation.

In the agreement that followed relations between the British Indian and Afghan governments, as previously arranged, were confirmed; and an understanding was reached upon the important and difficult subject of the border line of Afghanistan on the east, towards India. A Royal Commission was set up to determine the boundary between Afghanistan and British Governed India was tasked to negotiate terms for agreeing to the Durand Line, between the two parties camped at Parachinar, now part of FATA Pakistan, which is near Khost, Afghanistan. From the British side the camp was attended by Mortimer Durand and Sahibzada Abdul Qayyum, Political Agent Khyber. Afghanistan was represented by Sahibzada Abdul Latif and the Governor Sardar Shireendil Khan representing Amir Abdur Rahman Khan. In 1893, Mortimer Durand negotiated with Abdur Rahman Khan the Durand Line Treaty for the demarcation of the frontier between Afghanistan, the FATA, North-West Frontier Province and Baluchistan Provinces of Pakistan the successor state of British India. In 1905, Amir Habibullah Khan signed a new agreement with the United Kingdom which confirmed the legality of Durand Line.[2] Similarly, the legality durand line was once again confirmed by King Amanullah Khan through the treaty of Rawalpindi in 1919.[2][11]

Durand Line was once again recognised as international border between Pakistan and Afghanistan by Sardar Mohammed Daoud Khan (former prime minister and later president of Afghanistan) during his visit to Pakistan in August 1976.[12][13][14]

Dictatorship and the "Iron Amir"

Abdur Rahman Khan's government was a military despotism resting upon a well-appointed army; it was administered through officials absolutely subservient to an inflexible will and controlled by a widespread system of espionage; while the exercise of his personal authority was too often stained by acts of unnecessary cruelty.[3] He held open courts for the receipt of petitioners and the dispensation of justice; and in the disposal of business he was indefatigable.

In the 1880s, the "Iron Emir" decided to strategically displace some members of different ethnic groups in order to bring better security. For example, he "uprooted troublesome Durrani and Ghilzai Pashtun tribes and transported them to Uzbek and Tajik populated areas in the north, where they could spy on local Dari-speaking, non-Pashtun ethnic groups and act as a screen against further Russian encroachments on Afghan territory."[15] From the end of 1888, the Amir spent eighteen months in his northern provinces bordering upon the Oxus, where he was engaged in pacifying the country that had been disturbed by revolts, and in punishing with a heavy hand all who were known or suspected to have taken any part in rebellion.[3]

In 1895–1896, Abdur Rahman directed the invasion of Kafiristan and the conversion of its indigenous peoples to Islam. The region was subsequently renamed Nuristan. In 1896, he adopted the title of Zia-ul-Millat-Wa-ud Din ("Light of the nation and religion"), and his zeal for the cause of Islam induced him to publish treatises on jihad.[3][16]

Chitral, Yarkand and Ferghana became shelters for refugees in 1887 and 1883 from Badakhshan who fled from the campaigns of Abdul Rahman.[17]

1888-1893 Uprisings of Hazaras

In the early 1890s some Hazara tribes revolted against Abdur Rahman. In 1888, the Amir's cousin, Ishak Khan, rebelled against him in the north; and also the Ghilzais (Hotakis, Tokhis and Andaris) revolted against him in 1887; but these enterprises came to nothing. As the Kabul Newsletters written by the British agents indicate, Abdul Rahman was an extremely ruthless man. He has been called 'The Dracula Amir' by some writers[5][8] According to Syed Askar Mousavi, "thousands of Hazara men, women, and children were sold as slaves in the markets of Kabul and Qandahar, while numerous towers of human heads were made from the defeated rebels as a warning to others who might challenge the rule of the Amir."[18] During this period some Hazaras migrated to Quetta in Balochistan, while smaller number moved to Mashhad in northeastern Iran. The crackdown resulted in mass killing, enslavement and displacement of the Hazaras.

Death and Descendants

Abdur Rahman died on October 1, 1901 inside his summer palace, being succeeded by his son Habibullah Khan.

Today, his descendants can be found in many places outside Afghanistan, such as in America, France, Germany, and even in Scandinavian countries such as Denmark. His two eldest sons, Habibullah Khan and Nasrullah Khan, were born at Samarkand. His youngest son, Mahomed Omar Jan, was born in 1889 of an Afghan mother, connected by descent with the Barakzai family.[3]

Legacy

Afghan society has mixed feelings about his rule. Some remember him as a ruler who initiated many programs for modernization and effectively prevented the country from being occupied by Russia and Britain during the Great Game. On the other hand, some sectors of Afghanistan remember him as a domestically violent and geopolitically weak ruler in that he was brought to power by the British and declared war on Afghan minorities instead of fighting the British who were deciding Afghanistan's foreign policy for him.[8]

Honours

- Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India (GCSI) – 1885

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB)- 1893

See also

- European influence in Afghanistan

- Lillias Hamilton (court physician to Amir Abdur Rahman Khan in the 1890s)

- List of monarchs of Afghanistan

- Pashtun colonization of northern Afghanistan

Notes

- However, his year of birth is given as 1830 in Chambers Biographical Dictionary, ISBN 0-550-18022-2, page 2

- "Why the Durand Line matters". The Diplomat. 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 38.

- "ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Khān". Retrieved 2013-07-15.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 37.

- The Far East and Australasia 2003. Eur. 2002. p. 62. ISBN 1-85743-133-2.

- Eugene Schuyler, Turkistan : notes of a journey in Russian Turkistan, Kokand, Bukhara and Kuldja, F.A. Praeger (1966), p. 136

- "'Abdor Rahman Khan". Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-Ak – Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2010. pp. 20. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 37–38.

- "Worthy Advice in the Affairs of the World and Religion: The Autobiography of Emir Abdur Rahman Khan". World Digital Library. 1885. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

- "Why Afghanistan's independence day remains problematic". TRT world. 29 August 2019. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019.

- Rasanayagam, Angelo (2005). Afghanistan: A Modern History. I.B. Tauris. p. 64.

- Dorronsoro, Gilles (2005). Revolution Unending: Afghanistan, 1979 to present. Hurst & Co. Publisher. p. 84.

- Nunan, Timothy (2016). Humanitarian Invasion: Global Development in Cold War Afghanistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 125.

- Tomsen, Peter (2011). The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic Terrorism, Tribal Conflicts, and the Failures of Great Powers. PublicAffairs. p. 42. ISBN 1-5864-8781-7. Retrieved 2013-07-15.

- Hasan Kawun Kakar, Government and Society in Afghanistan: the Reign of 'Abd al-Rahman Khan, University of Texas Press (1979), pp. 176-177

- Paul Bergne (15 June 2007). The Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic. I.B.Tauris. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-84511-283-7.

- "HAZĀRA ii. HISTORY". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abdur Rahman Khan. |

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ayub Khan |

Barakzai dynasty Emir of Afghanistan 31 May 1880 – 1 October 1901 |

Succeeded by Habibullah Khan |