Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate was an Islamic empire based in Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent for 320 years (1206–1526).[5][6] Five dynasties ruled over the Delhi Sultanate sequentially: the Mamluk/ Slave dynasty (1206–1290), the Khilji dynasty (1290–1320), the Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1414),[7] the Sayyid dynasty (1414–1451), and the Lodi dynasty (1451–1526).

Delhi Sultanate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1206–1526 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Persian (official),[2] Hindustani (since 1451)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Sultanate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1206–1210 | Qutb al-Din Aibak (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1517–1526 | Ibrahim Lodi (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Corps of Forty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 June 1206 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 December 1305 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Battle of Panipat | 21 April 1526 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Taka | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Bangladesh India Nepal Pakistan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of India |

Satavahana gateway at Sanchi, 1st century CE |

|

Ancient

|

|

Classical

|

|

|

|

Early modern

|

|

Modern

|

|

Related articles

|

It covered parts of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and some parts of southern Nepal.

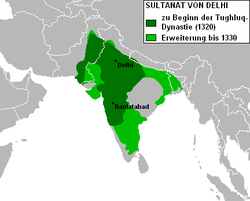

As a successor to the short-lived Ghurid empire, the Delhi Sultanate was originally one among a number of principalities ruled by Turkic slave-generals of Muhammad Ghori, who had conquered large parts of northern India, including Yildiz, Aibek and Qubacha, that had inherited and divided the Ghurid territories amongst themselves.[8] After a long period of infighting, the Mamluks were overthrown in the Khalji revolution which marked the transfer of power from the Turks to a heterogenous Indo-Mussalman nobility.[9][10] Both of the resulting Khalji and Tughlaq dynasties respectively saw a new wave of rapid Muslim conquests deep into South India.[11] The sultanate finally reached the peak of its geographical reach during the Tughlaq Dynasty, occupying most of the Indian subcontinent.[12] This was followed by decline due to Hindu reconquests, states such as the Vijayanagara Empire and Mewar asserting independence, and new Muslim sultanates such as the Bengal Sultanate breaking off.[13][14] In 1526, the Sultanate was conquered and succeeded by the Mughal Empire.

The sultanate is noted for its integration of the Indian subcontinent into a global cosmopolitan culture[15] (as seen concretely in the development of the Hindustani language[16] and Indo-Islamic architecture[17][18]), being one of the few powers to repel attacks by the Mongols (from the Chagatai Khanate)[19] and for enthroning one of the few female rulers in Islamic history, Razia Sultana, who reigned from 1236 to 1240.[20] Bakhtiyar Khalji's annexations were responsible for the large-scale desecration of Hindu and Buddhist temples[21] (leading to the decline of Buddhism in East India and Bengal[22][23]), and the destruction of universities and libraries.[24][25] Mongolian raids on West and Central Asia set the scene for centuries of migration of fleeing soldiers, learned men, mystics, traders, artists, and artisans from those regions into the subcontinent, thereby establishing Islamic culture in India.[26][27]

History

Background

The context behind the rise of the Delhi Sultanate in India was part of a wider trend affecting much of the Asian continent, including the whole of southern and western Asia: the influx of nomadic Turkic peoples from the Central Asian steppes. This can be traced back to the 9th century when the Islamic Caliphate began fragmenting in the Middle East, where Muslim rulers in rival states began enslaving non-Muslim nomadic Turks from the Central Asian steppes and raising many of them to become loyal military slaves called Mamluks. Soon, Turks were migrating to Muslim lands and becoming Islamicized. Many of the Turkic Mamluk slaves eventually rose up to become rulers, and conquered large parts of the Muslim world, establishing Mamluk Sultanates from Egypt to Afghanistan, before turning their attention to the Indian subcontinent.[28]

It is also part of a longer trend predating the spread of Islam. Like other settled, agrarian societies in history, those in the Indian subcontinent have been attacked by nomadic tribes throughout its long history. In evaluating the impact of Islam on the subcontinent, one must note that the northwestern subcontinent was a frequent target of tribes raiding from Central Asia in the pre-Islamic era. In that sense, the Muslim intrusions and later Muslim invasions were not dissimilar to those of the earlier invasions during the 1st millennium.[29]

By 962 AD, Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms in South Asia were under a wave of raids from Muslim armies from Central Asia.[30] Among them was Mahmud of Ghazni, the son of a Turkic Mamluk military slave,[31] who raided and plundered kingdoms in north India from east of the Indus river to west of Yamuna river seventeen times between 997 and 1030.[32] Mahmud of Ghazni raided the treasuries but retracted each time, only extending Islamic rule into western Punjab.[33][34]

The wave of raids on north Indian and western Indian kingdoms by Muslim warlords continued after Mahmud of Ghazni.[35] The raids did not establish or extend the permanent boundaries of their Islamic kingdoms. The Ghurid Sultan Mu'izz ad-Din Muhammad Ghori, commonly known as Muhammad of Ghor, began a systematic war of expansion into north India in 1173.[36] He sought to carve out a principality for himself by expanding the Islamic world.[32][37] Muhammad of Ghor sought a Sunni Islamic kingdom of his own extending east of the Indus river, and he thus laid the foundation for the Muslim kingdom called the Delhi Sultanate.[32] Some historians chronicle the Delhi Sultanate from 1192 due to the presence and geographical claims of Muhammad Ghori in South Asia by that time.[38]

Ghori was assassinated in 1206, by Ismāʿīlī Shia Muslims in some accounts or by Khokhars in others.[39] After the assassination, one of Ghori's slaves (or mamluks, Arabic: مملوك), the Turkic Qutb al-Din Aibak, assumed power, becoming the first Sultan of Delhi.[32]

Dynasties

| Delhi Sultanate | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruling dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Mamluk

Qutb al-Din Aibak, a former slave of Mu'izz ad-Din Muhammad Ghori (known more commonly as Muhammad of Ghor), was the first ruler of the Delhi Sultanate. Aibak was of Cuman-Kipchak (Turkic) origin, and due to his lineage, his dynasty is known as the Mamluk (Slave origin) dynasty (not to be confused with the Mamluk dynasty of Iraq or the Mamluk dynasty of Egypt).[40] Aibak reigned as the Sultan of Delhi for four years, from 1206 to 1210. Aibak was known for his generosity and people called him Lakhdata [41]

After Aibak died, Aram Shah assumed power in 1210, but he was assassinated in 1211 by Aibak's adopted son, Shams ud-Din Iltutmish.[42] Iltutmish's power was precarious, and a number of Muslim amirs (nobles) challenged his authority as they had been supporters of Qutb al-Din Aibak. After a series of conquests and brutal executions of opposition, Iltutmish consolidated his power.[43] His rule was challenged a number of times, such as by Qubacha, and this led to a series of wars.[44] Iltutmish conquered Multan and Bengal from contesting Muslim rulers, as well as Ranthambore and Siwalik from the Hindu rulers. He also attacked, defeated, and executed Taj al-Din Yildiz, who asserted his rights as heir to Mu'izz ad-Din Muhammad Ghori.[45] Iltutmish's rule lasted till 1236. Following his death, the Delhi Sultanate saw a succession of weak rulers, disputing Muslim nobility, assassinations, and short-lived tenures. Power shifted from Rukn ud-Din Firuz to Razia Sultana and others, until Ghiyas ud-Din Balban came to power and ruled from 1266 to 1287.[44][45] He was succeeded by 17-year-old Muiz ud-Din Qaiqabad, who appointed Jalal ud-Din Firuz Khalji as the commander of the army. Khalji assassinated Qaiqabad and assumed power, thus ending the Mamluk dynasty and starting the Khalji dynasty.

Qutb al-Din Aibak initiated the construction of the Qutub Minar. It is known that Aibak started the construction of Qutb Minar but died without completing it. It was later completed by his son, Iltutmish.[46] The Quwwat-ul-Islam (Might of Islam) Mosque was built by Aibak, now a UNESCO world heritage site.[47] The Qutub Minar Complex or Qutb Complex was expanded by Iltutmish, and later by Ala ud-Din Khalji (the second ruler of the Khalji dynasty) in the early 14th century.[47][48] During the Mamluk dynasty, many nobles from Afghanistan and Persia migrated and settled in India, as West Asia came under Mongol siege.[49]

Khaljis

The Khalji dynasty was of Turko-Afghan heritage.[50][51][52][53] They were originally of Turkic origin. They had long been settled in present-day Afghanistan before proceeding to Delhi in India. The name "Khalji" refers to an Afghan town known as Qalati Khalji ("Fort of Ghilji").[54] They were treated by others as ethnic Pashtuns (Afghan) due to adoption of some Pashtun habits and customs.[55][56] As a result of this, the dynasty is referred to as "Turko-Afghan".[51][52][53] The dynasty later also had Indian ancestry, through Jhatyapali (daughter of Ramachandra of Devagiri), wife of Alauddin Khalji and mother of Shihabuddin Omar.[57]

The first ruler of the Khalji dynasty was Jalal ud-Din Firuz Khalji. Firuz Khalji had already gathered enough support among the Pashtuns for taking over the crown.[58] He came to power in 1290 after killing the last ruler of the Mamluk dynasty, Muiz ud-Din Qaiqabad, with the support of Pashtun and Turkic nobles. He was around 70 years old at the time of his ascension, and was known as a mild-mannered, humble and kind monarch to the general public.[59][60] Jalal ud-Din Firuz was of Turko Afghan origin,[61][62][63] and ruled for 6 years before he was murdered in 1296 by his nephew and son-in-law Juna Muhammad Khalji,[64] who later came to be known as Ala ud-Din Khalji.

Ala ud-Din began his military career as governor of Kara province, from where he led two raids on Malwa (1292) and Devagiri (1294) for plunder and loot. His military campaigning returned to these lands as well other south Indian kingdoms after he assumed power. He conquered Gujarat, Ranthambore, Chittor, and Malwa.[65] However, these victories were cut short because of Mongol attacks and plunder raids from the northwest. The Mongols withdrew after plundering and stopped raiding northwest parts of the Delhi Sultanate.[66]

After the Mongols withdrew, Ala ud-Din Khalji continued to expand the Delhi Sultanate into southern India with the help of generals such as Malik Kafur and Khusro Khan. They collected much war booty (anwatan) from those they defeated.[67] His commanders collected war spoils and paid ghanima (Arabic: الْغَنيمَة, a tax on spoils of war), which helped strengthen the Khalji rule. Among the spoils was the Warangal loot that included the famous Koh-i-noor diamond.[68]

Ala ud-Din Khalji changed tax policies, raising agriculture taxes from 20% to 50% (payable in grain and agricultural produce), eliminating payments and commissions on taxes collected by local chiefs, banned socialization among his officials as well as inter-marriage between noble families to help prevent any opposition forming against him, and he cut salaries of officials, poets, and scholars.[64] These tax policies and spending controls strengthened his treasury to pay the keep of his growing army; he also introduced price controls on all agriculture produce and goods in the kingdom, as well as controls on where, how, and by whom these goods could be sold. Markets called "shahana-i-mandi" were created.[69] Muslim merchants were granted exclusive permits and monopoly in these "mandis" to buy and resell at official prices. No one other than these merchants could buy from farmers or sell in cities. Those found violating these "mandi" rules were severely punished, often by mutilation. Taxes collected in the form of grain were stored in the kingdom's storage. During famines that followed, these granaries ensured sufficient food for the army.[64]

Historians note Ala ud-Din Khalji as being a tyrant. Anyone Ala ud-Din suspected of being a threat to this power was killed along with the women and children of that family. He grew to eventually distrust the majority of his nobles and favored only a handful of his own slaves and family. In 1298, between 15,000 and 30,000 people near Delhi, who had recently converted to Islam, were slaughtered in a single day, due to fears of an uprising.[70] He is also known for his cruelty against kingdoms he defeated in battle.

After Ala ud-Din's death in 1316, his eunuch general Malik Kafur, who was born to a Hindu family but converted to Islam, assumed de-facto power and was supported by non-Khalaj nobles like the Pashtuns, notably Kamal al-Din Gurg. However he lacked the support of the majority of Khalaj nobles who had him assassinated, hoping to take power for themselves.[64] However the new ruler had the killers of Karfur executed.

The last Khalji ruler was Ala ud-Din Khalji's 18-year-old son Qutb ud-Din Mubarak Shah Khalji, who ruled for four years before he was killed by Khusro Khan, another slave-general with Hindu origins, who reverted from Islam and favoured his Hindu Baradu military clan in the nobility. Khusro Khan's reign lasted only a few months, when Ghazi Malik, later to be called Ghiyath al-Din Tughlaq, defeated him with the help of Punjabi Khokhar tribesmen and assumed power in 1320, thus ending the Khalji dynasty and starting the Tughlaq dynasty.[49][70]

Tughlaq

The Tughlaq dynasty lasted from 1320 to nearly the end of the 14th century. The first ruler Ghazi Malik renamed himself Ghiyath al-Din Tughlaq and is also referred to in scholarly works as Tughlak Shah. He was of "humble origins" but generally considered of a mixed Turko-Indian people.[1] Ghiyath al-Din ruled for five years and built a town near Delhi named Tughlaqabad.[71] According to some historians such as Vincent Smith,[72] he was killed by his son Juna Khan, who then assumed power in 1325. Juna Khan renamed himself Muhammad bin Tughlaq and ruled for 26 years.[73] During his rule, Delhi Sultanate reached its peak in terms of geographical reach, covering most of the Indian subcontinent.[12]

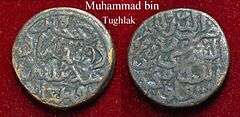

Muhammad bin Tughlaq was an intellectual, with extensive knowledge of the Quran, Fiqh, poetry and other fields. He was also deeply suspicious of his kinsmen and wazirs (ministers), extremely severe with his opponents, and took decisions that caused economic upheaval. For example, he ordered minting of coins from base metals with face value of silver coins - a decision that failed because ordinary people minted counterfeit coins from base metal they had in their houses and used them to pay taxes and jizya.[12][72]

On another occasion, after becoming upset by some accounts, or to run the Sultanate from the center of India by other accounts, Muhammad bin Tughlaq ordered the transfer of his capital from Delhi to Devagiri in modern-day Maharashtra (renaming it to Daulatabad), by forcing the mass migration of Delhi's population. One blind person who failed to move to Daulatabad was dragged for the entire journey of 40 days - the man died, his body fell apart, and only his tied leg reached Daulatabad.[72] The capital move failed because Daulatabad was arid and did not have enough drinking water to support the new capital. The capital then returned to Delhi. Nevertheless, Muhammad bin Tughlaq's orders affected history as a large number of Delhi Muslims who came to the Deccan area did not return to Delhi to live near Muhammad bin Tughlaq. This influx of the then-Delhi residents into the Deccan region led to a growth of Muslim population in central and southern India.[12] Muhammad bin Tughlaq's adventures in the Deccan region also marked campaigns of destruction and desecration of Hindu and Jain temples, for example the Swayambhu Shiva Temple and the Thousand Pillar Temple.[25]

Revolts against Muhammad bin Tughlaq began in 1327, continued over his reign, and over time the geographical reach of the Sultanate shrunk. The Vijayanagara Empire originated in southern India as a direct response to attacks from the Delhi Sultanate.,[74] and liberated south India from the Delhi Sultanate's rule.[75] In 1330s, Muhammad bin Tughlaq ordered an invasion of China, sending part of his forces over the Himalayas. However, they were defeated by the Hindu kingdom of Kangra.[76] Few survived the journey, and they were executed upon their return for failing.[72] During his reign, state revenues collapsed from his policies such as the base metal coins from 1329–1332. To cover state expenses, he sharply raised taxes. Those who failed to pay taxes were hunted and executed. Famines, widespread poverty, and rebellion grew across the kingdom. In 1338 his own nephew rebelled in Malwa, whom he attacked, caught, and flayed alive. By 1339, the eastern regions under local Muslim governors and southern parts led by Hindu kings had revolted and declared independence from the Delhi Sultanate. Muhammad bin Tughlaq did not have the resources or support to respond to the shrinking kingdom.[77] The historian Walford chronicled Delhi and most of India faced severe famines during Muhammad bin Tughlaq's rule in the years after the base metal coin experiment.[78][79] By 1347, the Bahmani Sultanate had become an independent and competing Muslim kingdom in Deccan region of South Asia.[30]

Muhammad bin Tughlaq died in 1351 while trying to chase and punish people in Gujarat who were rebelling against the Delhi Sultanate.[77] He was succeeded by Firuz Shah Tughlaq (1351–1388), who tried to regain the old kingdom boundary by waging a war with Bengal for 11 months in 1359. However, Bengal did not fall. Firuz Shah ruled for 37 years. His reign attempted to stabilize the food supply and reduce famines by commissioning an irrigation canal from the Yamuna river. An educated sultan, Firuz Shah left a memoir.[83] In it he wrote that he banned the practice of torture, such as amputations, tearing out of eyes, sawing people alive, crushing people's bones as punishment, pouring molten lead into throats, setting people on fire, driving nails into hands and feet, among others.[84] He also wrote that he did not tolerate attempts by Rafawiz Shia Muslim and Mahdi sects from proselytizing people into their faith, nor did he tolerate Hindus who tried to rebuild temples that his armies had destroyed.[85] As punishment for proselytizing, Firuz Shah put many Shias, Mahdi, and Hindus to death (siyasat). Firuz Shah Tughlaq also lists his accomplishments to include converting Hindus to Sunni Islam by announcing an exemption from taxes and jizya for those who convert, and by lavishing new converts with presents and honours. Simultaneously, he raised taxes and jizya, assessing it at three levels, and stopping the practice of his predecessors who had historically exempted all Hindu Brahmins from the jizya.[84][86] He also vastly expanded the number of slaves in his service and those of Muslim nobles. The reign of Firuz Shah Tughlaq was marked by reduction in extreme forms of torture, eliminating favours to select parts of society, but also increased intolerance and persecution of targeted groups.[84] {Too much reliance on one reference Smith???}

The death of Firuz Shah Tughlaq created anarchy and disintegration of the kingdom. The last rulers of this dynasty both called themselves Sultan from 1394 to 1397: Nasir ud-Din Mahmud Shah Tughlaq, the grandson of Firuz Shah Tughlaq who ruled from Delhi, and Nasir ud-Din Nusrat Shah Tughlaq, another relative of Firuz Shah Tughlaq who ruled from Firozabad, which was a few miles from Delhi.[87] The battle between the two relatives continued till Timur's invasion in 1398. Timur, also known as Tamerlane in Western scholarly literature, was the Turkicized Mongol ruler of the Timurid Empire. He became aware of the weakness and quarreling of the rulers of the Delhi Sultanate, so he marched with his army to Delhi, plundering and killing all the way.[88][89] Estimates for the massacre by Timur in Delhi range from 100,000 to 200,000 people.[90][91] Timur had no intention of staying in or ruling India. He looted the lands he crossed, then plundered and burnt Delhi. Over five days, Timur and his army raged a massacre. Then he collected and carried the wealth, captured women and slaves (particularly skilled artisans), and returned to Samarkand. The people and lands within the Delhi Sultanate were left in a state of anarchy, chaos, and pestilence.[87] Nasir ud-Din Mahmud Shah Tughlaq, who had fled to Gujarat during Timur's invasion, returned and nominally ruled as the last ruler of Tughlaq dynasty, as a puppet of various factions at the court.[92]

Sayyid

The Sayyid dynasty ruled the Delhi Sultanate from 1415 to 1451.[30] The Timurid invasion and plunder had left the Delhi Sultanate in shambles, and little is known about the rule by the Sayyid dynasty. Annemarie Schimmel notes the first ruler of the dynasty as Khizr Khan, who assumed power by claiming to represent Timur. His authority was questioned even by those near Delhi. His successor was Mubarak Khan, who renamed himself Mubarak Shah and tried to regain lost territories in Punjab from Khokhar warlords, unsuccessfully.[92]

With the power of the Sayyid dynasty faltering, Islam's history on the Indian subcontinent underwent a profound change, according to Schimmel.[92] The previously dominant Sunni sect of Islam became diluted, alternate Muslim sects such as Shia rose, and new competing centers of Islamic culture took roots beyond Delhi.

The Sayyid dynasty was displaced by the Lodi dynasty in 1451.

Lodi

The Lodi dynasty belonged to the Pashtun[93] (Afghan) Lodi tribe.[94] Bahlul Khan Lodi started the Lodi dynasty and was the first Pashtun, to rule the Delhi Sultanate.[95] Bahlul Lodi began his reign by attacking the Muslim Jaunpur Sultanate to expand the influence of the Delhi Sultanate, and was partially successful through a treaty. Thereafter, the region from Delhi to Varanasi (then at the border of Bengal province), was back under influence of Delhi Sultanate.

After Bahlul Lodi died, his son Nizam Khan assumed power, renamed himself Sikandar Lodi and ruled from 1489 to 1517.[96] One of the better known rulers of the dynasty, Sikandar Lodi expelled his brother Barbak Shah from Jaunpur, installed his son Jalal Khan as the ruler, then proceeded east to make claims on Bihar. The Muslim governors of Bihar agreed to pay tribute and taxes, but operated independent of the Delhi Sultanate. Sikandar Lodi led a campaign of destruction of temples, particularly around Mathura. He also moved his capital and court from Delhi to Agra,[97] an ancient Hindu city that had been destroyed during the plunder and attacks of the early Delhi Sultanate period. Sikandar thus erected buildings with Indo-Islamic architecture in Agra during his rule, and the growth of Agra continued during the Mughal Empire, after the end of the Delhi Sultanate.[95][98]

Sikandar Lodi died a natural death in 1517, and his second son Ibrahim Lodi assumed power. Ibrahim did not enjoy the support of Afghan and Persian nobles or regional chiefs.[99] Ibrahim attacked and killed his elder brother Jalal Khan, who was installed as the governor of Jaunpur by his father and had the support of the amirs and chiefs.[95] Ibrahim Lodi was unable to consolidate his power, and after Jalal Khan's death, the governor of Punjab, Daulat Khan Lodi, reached out to the Mughal Babur and invited him to attack the Delhi Sultanate.[100] Babur defeated and killed Ibrahim Lodi in the Battle of Panipat in 1526. The death of Ibrahim Lodi ended the Delhi Sultanate, and the Mughal Empire replaced it.

Government and politics

The Delhi Sultanate continued the governmental conventions of the previous Hindu polities, claiming paramountcy rather than exclusive supreme control. Accordingly, it did not interfere with the autonomy and military of conquered Hindu rulers, and freely included Hindu vassals and officials.[5]

Economic policy and administration

The economic policy of the Delhi Sultanate was characterized by greater government involvement in the economy relative to the Classical Hindu dynasties, and increased penalties for private businesses that broke government regulations. Alauddin Khalji replaced the private markets with four centralized government-run markets, appointed a "market controller", and implemented strict price controls[101] on all kinds of goods, "from caps to socks; from combs to needles; from vegetables, soups, sweetmeats to chapatis" (according to Ziauddin Barani (c. 1357)[102]). The price controls were inflexible even during droughts.[103] Capitalist investors were completely banned from participating in horse trade,[104] animal and slave brokers were forbidden from collecting commissions,[105] and private merchants were eliminated from all animal and slave markets.[105] Bans were instituted against hoarding[106] and regrating,[107] granaries were nationalized[106] and limits were placed on the amount of grain that could be used by cultivators for personal use.[108]

Various licensing rules were imposed. Registration of merchants was required,[109] and expensive goods such as certain fabrics were deemed "unnecessary" for the general public and required a permit from the state to be purchased. These licenses were issued to amirs, maliks, and other important persons in government.[105] Agricultural taxes were raised to 50%.

Traders regarded the regulations as burdensome, and violations were severely punished, leading to further resentment among the traders.[110] A network of spies was instituted to ensure the implementation of the system; even after price controls were lifted after Khalji's death, Barani claims that the fear of his spies remained, and that people continued to avoid trading in expensive commodities.[111]

Social policies

The sultanate enforced Islamic religious prohibitions of anthropomorphic representations in art.[112]

Military

The bulk of Delhi Sultanate's army originally consisted of nomadic Turkic Mamluk military slaves, who were skilled in nomadic cavalry warfare. A major military contribution of the Delhi Sultanate was their successful campaigns in repelling the Mongol Empire's invasions of India, which could have been devastating for the Indian subcontinent, like the Mongol invasions of China, Persia and Europe. The Delhi Sultanate's Mamluk army were skilled in the same style of nomadic cavalry warfare used by the Mongols, making them successful in repelling the Mongol invasions, as was the case for the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. Were it not for the Delhi Sultanate, it is possible that the Mongol Empire may have been successful in invading India.[28] The strength of the armies changes according to time.

Attacks on civilians

Destruction of cities

While the sacking of cities was not uncommon in medieval warfare, the army of the Delhi Sultanate also often completely destroyed cities in their military expeditions. According to Jain chronicler Jinaprabha Suri, Khalji's conquests destroyed hundreds of towns including Ashapalli (modern-day Ahmedabad), Vanthali and Surat in Gujarat.[113] This account is corroborated by Ziauddin Barani.[114]

Massacres

- Ghiyas ud din Balban wiped out the Rajputs of Mewat and Awadh, killing approximately 100,000 people.[115]

- Alauddin Khalji ordered the killing of 30,000 people at Chittor.[116]

- Alauddin Khalji ordered the killing of several prominent Brahmin and merchant civilians as ransom during his raid on Devagiri.[117]

- Muhammad bin Tughlaq killed 12,000 Hindu ascetics during the sacking of Srirangam.[118]

- Firuz Shah Tughlaq killed 180,000 people during his invasion of Bengal.[119]

Desecration of temples, universities and libraries

Historian Richard Eaton has tabulated a campaign of destruction of idols and temples by Delhi Sultans, intermixed with instances of years where the temples were protected from desecration.[21][120][121] In his paper, he has listed 37 instances of Hindu temples being desecrated or destroyed in India during the Delhi Sultanate, from 1234 to 1518, for which reasonable evidences are available.[122][123][124] He notes that this was not unusual in medieval India, as there were numerous recorded instances of temple desecration by Hindu and Buddhist kings against rival Indian kingdoms between 642 and 1520, involving conflict between devotees of different Hindu deities, as well as between Hindus, Buddhists and Jains.[125][126][127] He also noted there were also many instances of Delhi sultans, who often had Hindu ministers, ordering the protection, maintenance and repairing of temples, according to both Muslim and Hindu sources. For example, a Sanskrit inscription notes that Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq repaired a Siva temple in Bidar after his Deccan conquest. There was often a pattern of Delhi sultans plundering or damaging temples during conquest, and then patronizing or repairing temples after conquest. This pattern came to an end with the Mughal Empire, where Akbar the Great's chief minister Abu'l-Fazl criticized the excesses of earlier sultans such as Mahmud of Ghazni.[122]

In many cases, the demolished remains, rocks and broken statue pieces of temples destroyed by Delhi sultans were reused to build mosques and other buildings. For example, the Qutb complex in Delhi was built from stones of 27 demolished Hindu and Jain temples by some accounts.[128] Similarly, the Muslim mosque in Khanapur, Maharashtra was built from the looted parts and demolished remains of Hindu temples.[49] Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji destroyed Buddhist and Hindu libraries and their manuscripts at Nalanda and Odantapuri Universities in 1193 AD at the beginning of the Delhi Sultanate.[25][129]

The first historical record of a campaign of destruction of temples and defacement of faces or heads of Hindu idols lasted from 1193 to 1194 in Rajasthan, Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh under the command of Ghuri. Under the Mamluks and Khaljis, the campaign of temple desecration expanded to Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Maharashtra, and continued through the late 13th century.[21] The campaign extended to Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu under Malik Kafur and Ulugh Khan in the 14th century, and by the Bahmanis in 15th century.[25] Orissa temples were destroyed in the 14th century under the Tughlaqs.

Beyond destruction and desecration, the sultans of the Delhi Sultanate in some cases had forbidden reconstruction of damaged Hindu, Jain and Buddhist temples, and they prohibited repairs of old temples or construction of any new temples.[130][131] In certain cases, the Sultanate would grant a permit for repairs and construction of temples if the patron or religious community paid jizya (fee, tax). For example, a proposal by the Chinese to repair Himalayan Buddhist temples destroyed by the Sultanate army was refused, on the grounds that such temple repairs were only allowed if the Chinese agreed to pay jizya tax to the treasury of the Sultanate.[132][133] In his memoirs, Firoz Shah Tughlaq describes how he destroyed temples and built mosques instead and killed those who dared build new temples.[134] Other historical records from wazirs, amirs and the court historians of various Sultans of the Delhi Sultanate describe the grandeur of idols and temples they witnessed in their campaigns and how these were destroyed and desecrated.[135]

| Sultan / Agent | Dynasty | Years | Temple Sites Destroyed | States |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muhammad Ghori, Qutb al-Din Aibak | Mamluk | 1193-1290 | Ajmer, Samana, Kuhram, Delhi, Kol, Varanasi | Rajasthan, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh |

| Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji, Shams ud-Din Iltumish, Jalal ud-Din Firuz Khalji, Ala ud-Din Khalji, Malik Kafur | Mamluk and Khalji | 1290-1320 | Nalanda, Odantapuri, Vikramashila, Bhilsa, Ujjain, Jhain, Vijapur, Devagiri, Somnath, Chidambaram, Madurai | Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu |

| Ulugh Khan, Firuz Shah Tughlaq, Raja Nahar Khan, Muzaffar Khan | Khalji and Tughlaq | 1320-1395[137] | Somnath, Warangal, Bodhan, Pillalamarri, Puri, Sainthali, Idar[138] | Gujarat, Telangana, Orissa, Haryana |

| Sikandar, Muzaffar Shah, Ahmad Shah, Mahmud | Sayyid | 1400-1442 | Paraspur, Bijbehara, Tripuresvara, Idar, Diu, Manvi, Sidhpur, Delwara, Kumbhalmer | Gujarat, Rajasthan |

| Suhrab, Begdha, Bahmani, Khalil Shah, Khawwas Khan, Sikandar Lodi, Ibrahim Lodi | Lodi | 1457-1518 | Mandalgarh, Malan, Dwarka, Kondapalle, Kanchi, Amod, Nagarkot, Utgir, Narwar, Gwalior | Rajasthan, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh |

- Iconoclasm under the Delhi Sultanate

.jpg) The Somnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Muslim armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 CE.[139]

The Somnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Muslim armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 CE.[139].jpg) The Kashi Vishwanath Temple was destroyed by the army of Qutb-ud-din Aibak.[140]

The Kashi Vishwanath Temple was destroyed by the army of Qutb-ud-din Aibak.[140]

The armies of Delhi Sultanate led by Muslim Commander Malik Kafur plundered the Meenakshi Temple and looted it of its valuables.[142][143][144]

The armies of Delhi Sultanate led by Muslim Commander Malik Kafur plundered the Meenakshi Temple and looted it of its valuables.[142][143][144] Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[21]

Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[21] Rani ki vav is a stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan; the city was sacked by Sultan of Delhi Qutb-ud-din Aybak between 1200 and 1210, and again by the Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[145]

Rani ki vav is a stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan; the city was sacked by Sultan of Delhi Qutb-ud-din Aybak between 1200 and 1210, and again by the Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[145] Artistic rendition of the Kirtistambh at Rudra Mahalaya Temple. The temple was destroyed by Alauddin Khalji.[146]

Artistic rendition of the Kirtistambh at Rudra Mahalaya Temple. The temple was destroyed by Alauddin Khalji.[146] Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[147]

Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[147]

Economy

Many historians argue that the Delhi Sultanate was responsible for making India more multicultural and cosmopolitan. The establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in India has been compared to the expansion of the Mongol Empire, and called "part of a larger trend occurring throughout much of Eurasia, in which nomadic people migrated from the steppes of Inner Asia and became politically dominant".[15]

According to Angus Maddison, between the years 1000 and 1500, India's GDP, of which the sultanates represented a significant part, grew nearly 80% to $60.5 billion in 1500.[148] However, these numbers should be viewed in context: according to Maddison's estimates, India's population grew by nearly 50% in the same time period,[149] amounting to a per-capita GDP growth of around 20%. World GDP more than doubled in the same period, and India's per-capita GDP fell behind that of China, with which it was previously at par. India's GDP share of the world declined under the Delhi Sultanate from nearly 30% to 25%, and would continue to decline until the mid-20th century.

In terms of mechanical devices, later Mughal emperor Babur provides a description of the use of the water-wheel in the Delhi Sultanate,[150] which some historians have taken to suggest that the water-wheel was introduced to India under the Delhi Sultanate.[151] However this has been criticized e.g. by Siddiqui,[152] and there is significant evidence that the device existed in India prior to this.[note 1] Some have also suggested[157] that the spinning wheel was introduced to India from Iran during the Delhi Sultanate, though most scholars believe that it was invented in India in the first millennium.[158] The worm gear roller cotton gin was invented in the thirteenth or fourteenth centuries: however, Irfan Habib states that the development likely occurred in Peninsular India,[159] which was not under the rule of the Delhi Sultanate (except for a brief invasion by Tughlaq between 1330-1335).

Although India was the first region outside China to use paper and papermaking reached India as early as the 6th to 7th centuries,[160][161][162][163] its use only became widespread in Northern India in the 13th century, and Southern India between the 15th and 16th centuries.[164] However, it is not clear if this change can be attributed to the Delhi Sultanate, as 15th century Chinese traveler Ma Huan remarks that Indian paper was white and made from "bark of a tree", similar to the Chinese method of papermaking (as opposed to the Middle-Eastern method of using rags and waste material), suggesting a direct route from China for the arrival of paper.[165]

Society

Demographics

According to one set of the very uncertain estimates of modern historians, the total Indian population had largely been stagnant at 75 million during the Middle Kingdoms era from 1 AD to 1000 AD. During the Medieval Delhi Sultanate era from 1000 to 1500, India as a whole experienced lasting population growth for the first time in a thousand years, with its population increasing nearly 50% to 110 million by 1500 AD.[166][167]

Culture

While the Indian subcontinent has had invaders from Central Asia since ancient times, what made the Muslim invasions different is that unlike the preceding invaders who assimilated into the prevalent social system, the successful Muslim conquerors retained their Islamic identity and created new legal and administrative systems that challenged and usually in many cases superseded the existing systems of social conduct and ethics, even influencing the non-Muslim rivals and common masses to a large extent, though the non-Muslim population was left to their own laws and customs.[168][169] They also introduced new cultural codes that in some ways were very different from the existing cultural codes. This led to the rise of a new Indian culture which was mixed in nature, different from ancient Indian culture. The overwhelming majority of Muslims in India were Indian natives converted to Islam. This factor also played an important role in the synthesis of cultures.[170]

The Hindustani language (Hindi/Urdu) began to emerge in the Delhi Sultanate period, developed from the Middle Indo-Aryan apabhramsha vernaculars of North India. Amir Khusro, who lived in the 13th century CE during the Delhi Sultanate period in North India, used a form of Hindustani, which was the lingua franca of the period, in his writings and referred to it as Hindavi.[16]

Architecture

The start of the Delhi Sultanate in 1206 under Qutb al-Din Aibak introduced a large Islamic state to India, using Central Asian styles.[171] The types and forms of large buildings required by Muslim elites, with mosques and tombs much the most common, were very different from those previously built in India. The exteriors of both were very often topped by large domes, and made extensive use of arches. Both of these features were hardly used in Hindu temple architecture and other indigenous Indian styles. Both types of building essentially consist of a single large space under a high dome, and completely avoid the figurative sculpture so important to Hindu temple architecture.[172]

The important Qutb Complex in Delhi was begun under Muhammad of Ghor, by 1199, and continued under Qutb al-Din Aibak and later sultans. The Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque, now a ruin, was the first structure. Like other early Islamic buildings it re-used elements such as columns from destroyed Hindu and Jain temples, including one on the same site whose platform was reused. The style was Iranian, but the arches were still corbelled in the traditional Indian way.[173]

Beside it is the extremely tall Qutb Minar, a minaret or victory tower, whose original four stages reach 73 meters (with a final stage added later). Its closest comparator is the 62-metre all-brick Minaret of Jam in Afghanistan, of c.1190, a decade or so before the probable start of the Delhi tower.[174] The surfaces of both are elaborately decorated with inscriptions and geometric patterns; in Delhi the shaft is fluted with "superb stalactite bracketing under the balconies" at the top of each stage.[175] In general minarets were slow to be used in India, and are often detached from the main mosque where they exist.[176]

The Tomb of Iltutmish was added by 1236; its dome, the squinches again corbelled, is now missing, and the intricate carving has been described as having an "angular harshness", from carvers working in an unfamiliar tradition.[177] Other elements were added to the complex over the next two centuries.

Another very early mosque, begun in the 1190s, is the Adhai Din Ka Jhonpra in Ajmer, Rajasthan, built for the same Delhi rulers, again with corbelled arches and domes. Here Hindu temple columns (and possibly some new ones) are piled up in threes to achieve extra height. Both mosques had large detached screens with pointed corbelled arches added in front of them, probably under Iltutmish a couple of decades later. In these the central arch is taller, in imitation of an iwan. At Ajmer the smaller screen arches are tentatively cusped, for the first time in India.[178]

.jpg)

By around 1300 true domes and arches with voussoirs were being built; the ruined Tomb of Balban (d. 1287) in Delhi may be the earliest survival.[179] The Alai Darwaza gatehouse at the Qutb complex, from 1311, still shows a cautious approach to the new technology, with very thick walls and a shallow dome, only visible from a certain distance or height. Bold contrasting colours of masonry, with red sandstone and white marble, introduce what was to become a common feature of Indo-Islamic architecture, substituting for the polychrome tiles used in Persia and Central Asia. The pointed arches come together slightly at their base, giving a mild horseshoe arch effect, and their internal edges are not cusped but lined with conventionalized "spearhead" projections, possibly representing lotus buds. Jali, stone openwork screens, are introduced here; they already had been long used in temples.[180]

Tughlaq architecture

The tomb of Shah Rukn-e-Alam (built 1320 to 1324) in Multan, Pakistan is a large octagonal brick-built mausoleum with polychrome glazed decoration that remains much closer to the styles of Iran and Afghanistan. Timber is also used internally. This was the earliest major monument of the Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1413), built during the unsustainable expansion of its massive territory. It was built for a Sufi saint rather than a sultan, and most of the many Tughlaq tombs are much less exuberant. The tomb of the founder of the dynasty, Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq (d. 1325) is more austere, but impressive; like a Hindu temple, it is topped with a small amalaka and a round finial like a kalasha. Unlike the buildings mentioned previously, it completely lacks carved texts, and sits in a compound with high walls and battlements. Both these tombs have external walls sloping slightly inwards, by 25° in the Delhi tomb, like many fortifications including the ruined Tughlaqabad Fort opposite the tomb, intended as the new capital.[181]

The Tughlaqs had a corps of government architects and builders, and in this and other roles employed many Hindus. They left many buildings, and a standardized dynastic style.[180] The third sultan, Firuz Shah (r. 1351-88) is said to have designed buildings himself, and was the longest ruler and greatest builder of the dynasty. His Firoz Shah Palace Complex (started 1354) at Hisar, Haryana is a ruin, but parts are in fair condition.[182] Some buildings from his reign take forms that had been rare or unknown in Islamic buildings.[183] He was buried in the large Hauz Khas Complex in Delhi, with many other buildings from his period and the later Sultanate, including several small domed pavilions supported only by columns.[184]

By this time Islamic architecture in India had adopted some features of earlier Indian architecture, such as the use of a high plinth,[185] and often mouldings around its edges, as well as columns and brackets and hypostyle halls.[186] After the death of Firoz the Tughlaqs declined, and the following Delhi dynasties were weak. Most of the monumental buildings constructed were tombs, although the impressive Lodi Gardens in Delhi (adorned with fountains, charbagh gardens, ponds, tombs and mosques) were constructed by the late Lodi dynasty. The architecture of other regional Muslim states was often more impressive.[187]

.jpg)

Mausoleum of Iltutmish, Delhi, by 1236, with corbel arches

Mausoleum of Iltutmish, Delhi, by 1236, with corbel arches Possibly the first "true" arches in India; Tomb of Balban (d. 1287) in Delhi

Possibly the first "true" arches in India; Tomb of Balban (d. 1287) in Delhi Pavilions in the Hauz Khas Complex, Delhi

Pavilions in the Hauz Khas Complex, Delhi- Tomb of Sikander Lodi in the Lodi Gardens, Delhi

See also

Notes

- Pali literature dating to the 4th century BC mentions the cakkavattaka, which commentaries explain as arahatta-ghati-yanta (machine with wheel-pots attached), and according to Pacey, water-raising devices were used for irrigation in Ancient India predating their use in the Roman empire or China.[153] Greco-Roman tradition, on the other hand, asserts that the device was introduced to India from the Roman Empire.[154] Furthermore, South Indian mathematician Bhaskara II describes water-wheels c. 1150 in his incorrect proposal for a perpetual motion machine.[155] Srivastava argues that the Sakia, or araghatta was in fact invented in India by the 4th century.[156]

References

- Jamal Malik (2008). Islam in South Asia: A Short History. Brill Publishers. p. 104. ISBN 978-9004168596.

- "Arabic and Persian Epigraphical Studies - Archaeological Survey of India". Asi.nic.in. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Alam, Muzaffar (1998). "The pursuit of Persian: Language in Mughal Politics". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 32 (2): 317–349. doi:10.1017/s0026749x98002947.

Hindavi was recognized as a semi-official language by the Sor Sultans (1540–1555) and their chancellery rescripts bore transcriptions in the Devanagari script of the Persian contents. The practice is said to have been introduced by the Lodis (1451–1526).

- Jackson, Peter (16 October 2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.

- Delhi Sultanate, Encyclopædia Britannica

- A. Schimmel, Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, Leiden, 1980

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 68–102. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- K. A. Nizami (1992). A Comprehensive History of India: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206-1526). 5 (Second ed.). The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. p. 198.

- Mohammad Aziz Ahmad (1939). "THE FOUNDATION OF MUSLIM RULE IN INDIA. (1206-1290 A.D.)". Indian History Congress. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Satish Chandra (2004). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanat (1206-1526) - Part One. Har-Anand Publications.

- Krishna Gopal Sharma (1999). History and Culture of Rajasthan: From Earliest Times Upto 1956 A.D. Centre for Rajasthan Studies, University of Rajasthan.

- Muḥammad ibn Tughluq Encyclopædia Britannica

- Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, A History of India, 3rd Edition, Routledge, 1998, ISBN 0-415-15482-0, pp 187-190

- Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, Oxford University Press

- Asher, C. B.; Talbot, C (1 January 2008), India Before Europe (1st ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 50–52, ISBN 978-0-521-51750-8

- Keith Brown; Sarah Ogilvie (2008), Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7,

... Apabhramsha seemed to be in a state of transition from Middle Indo-Aryan to the New Indo-Aryan stage. Some elements of Hindustani appear ... the distinct form of the lingua franca Hindustani appears in the writings of Amir Khusro (1253–1325), who called it Hindwi ...

- A. Welch, "Architectural Patronage and the Past: The Tughluq Sultans of India", Muqarnas 10, 1993, Brill Publishers, pp 311-322

- J. A. Page, Guide to the Qutb, Delhi, Calcutta, 1927, page 2-7

- Pradeep Barua The State at War in South Asia, ISBN 978-0803213449, p. 29–30

- Bowering et al., The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought, ISBN 978-0691134840, Princeton University Press

- Richard Eaton (September 2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States". Journal of Islamic Studies. 11 (3): 283–319. doi:10.1093/jis/11.3.283.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, pages 184–185

- Craig Lockard (2007). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: Volume I: A Global History. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 364. ISBN 978-0-618-38612-3.

- Gul and Khan (2008)"Growth and Development of Oriental Libraries in India", ' Library Philosophy and Practice, University of Nebrasaka-Lincoln

- Richard Eaton, Temple Desecration and Muslim States in Medieval India at Google Books, (2004)

- Ludden 2002, p. 67.

- Asher & Talbot 2008, pp. 50–51.

- Asher, C. B.; Talbot, C (1 January 2008), India Before Europe (1st ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 19, 50–51, ISBN 978-0-521-51750-8

- Richard M. Frye, "Pre-Islamic and Early Islamic Cultures in Central Asia", in Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective, ed. Robert L. Canfield (Cambridge U. Press c. 1991), 35–53.

- See:

- M. Reza Pirbha, Reconsidering Islam in a South Asian Context, ISBN 978-9004177581, Brill

- The Islamic frontier in the east: Expansion into South Asia, Journal of South Asian Studies, 4(1), pp. 91-109

- Sookoohy M., Bhadreswar - Oldest Islamic Monuments in India, ISBN 978-9004083417, Brill Academic; see discussion of earliest raids in Gujarat

- Asher, C. B.; Talbot, C (1 January 2008), India Before Europe (1st ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 19, ISBN 978-0-521-51750-8

- Peter Jackson 2003, pp. 3-30.

- T. A. Heathcote, The Military in British India: The Development of British Forces in South Asia:1600-1947, (Manchester University Press, 1995), pp 5-7

- Barnett, Lionel (1999), Antiquities of India: An Account of the History and Culture of Ancient Hindustan, p. 1, at Google Books, Atlantic pp. 73–79

- Richard Davis (1994), Three styles in looting India, History and Anthropology, 6(4), pp 293-317, doi:10.1080/02757206.1994.9960832

- MUHAMMAD B. SAM Mu'izz AL-DIN, T.W. Haig, Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. VII, ed. C.E.Bosworth, E.van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs and C. Pellat, (Brill, 1993)

- C.E. Bosworth, Tidge History of Iran, Vol. 5, ed. J. A. Boyle, John Andrew Boyle, (Cambridge University Press, 1968), pp 161-170

- History of South Asia: A Chronological Outline Columbia University (2010)

- Muʿizz al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Sām Encyclopædia Britannica (2011)

- Jackson P. (1990), The Mamlūk institution in early Muslim India, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland (New Series), 122(02), pp 340-358

- https://ia800608.us.archive.org/25/items/ShahnamaEIslamPdfbooksfree.pk/Shahnama%20e%20Islam%20Pdfbooksfree.pk.pdf

- C.E. Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties, Columbia University Press (1996)

- Barnett & Haig (1926), A review of History of Mediaeval India, from ad 647 to the Mughal Conquest - Ishwari Prasad, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland (New Series), 58(04), pp 780-783

- Peter Jackson 2003, pp. 29-48.

- Anzalone, Christopher (2008), "Delhi Sultanate", in Ackermann, M. E. etc. (Editors), Encyclopedia of World History 2, ISBN 978-0-8160-6386-4

- "Qutub Minar". Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Qutb Minar and its Monuments, Delhi UNESCO

- Welch and Crane note that the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque was built with the remains of demolished Hindu and Jain temples; See: Welch, Anthony; Crane, Howard (1983). "The Tughluqs: Master Builders of the Delhi Sultanate" (PDF). Muqarnas. Brill. 1: 123–166. doi:10.2307/1523075. JSTOR 1523075. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- Welch, Anthony; Crane, Howard (1983). "The Tughluqs: Master Builders of the Delhi Sultanate" (PDF). Muqarnas. Brill. 1: 123–166. doi:10.2307/1523075. JSTOR 1523075. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- Khan, Hussain Ahmad (2014). Artisans, Sufis, Shrines: Colonial Architecture in Nineteenth-Century Punjab. I.B.Tauris. p. 15. ISBN 9781784530143.

- Yunus, Mohammad; Aradhana Parmar (2003). South Asia: a historical narrative. Oxford University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-1957-9711-4. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- Kumar Mandal, Asim (2003). The Sundarbans of India: A Development Analysis. India: Indus Publishing. p. 43. ISBN 978-81-738-7143-6. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- Singh, D. (1998). The Sundarbans of India: A Development Analysis. India: APH Publishing. p. 141. ISBN 978-81-702-4992-4. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- Thorpe, Showick Thorpe Edgar (2009). The Pearson General Studies Manual 2009, 1/e. Pearson Education India. p. 1900. ISBN 978-81-317-2133-9. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

The Khalji dynasty was named after a village in Afghanistan. Some historians believe that they were Afghans, but Bharani and Wolse Haig explain in their accounts that the rulers from this dynasty who came to India, though they had temporarily settled in Afghanistan, were originally Turkic.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of medieval India: from 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 28. ISBN 978-81-269-0123-4. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

The Khaljis were a Turkish tribe but having been long domiciled in Afghanistan, and adopted some Afghan habits and customs. They were treated as Afghans in Delhi Court.

- Cavendish, Marshall (2006). World and Its Peoples: The Middle East, Western Asia, and Northern Africa. Marshall Cavendish. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

The members of the new dynasty, although they were also Turkic, had settled in Afghanistan and brought a new set of customs and culture to Delhi.

- Kishori Saran Lal (1950). History of the Khaljis (1290-1320). Allahabad: The Indian Press. pp. 56–57. OCLC 685167335.

- Yunus, Mohammad; Parmar, Aradhana (2003). South Asia: A Historical Narrative. Oxford University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-19-579711-4.

Firuz Khalji had already gathered enough support among the Afghans for taking over the crown.

- A. L. Srivastava (1966). The Sultanate of Delhi, 711-1526 A.D. (Second ed.). Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. 141. OCLC 607636383.

- A. B. M. Habibullah (1992) [1970]. "The Khaljis: Jalaluddin Khalji". In Mohammad Habib; Khaliq Ahmad Nizami (eds.). A Comprehensive History of India. 5: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206-1526). The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. p. 312. OCLC 31870180.

- Puri, B. N.; Das, M. N. (1 December 2003). A Comprehensive History of India: Comprehensive history of medieval India. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9788120725089 – via Google Books.

- "Khilji Dynasty Map, Khilji Empire". www.mapsofindia.com.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (23 August 2002). History of Medieval India: From 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 9788126901234 – via Google Books.

- Holt et al., The Cambridge History of Islam - The Indian sub-continent, south-east Asia, Africa and the Muslim west, ISBN 978-0521291378, pp 9-13

- Alexander Mikaberidze, Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, ISBN 978-1598843361, pp 62-63

- Rene Grousset - Empire of steppes, Chagatai Khanate; Rutgers Univ Press, New Jersey, U.S.A, 1988 ISBN 0-8135-1304-9

- Frank Fanselow (1989), Muslim society in Tamil Nadu (India): an historical perspective, Journal Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs, 10(1), pp 264-289

- Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, A History of India, 3rd Edition, Routledge, 1998, ISBN 0-415-15482-0

- AL Srivastava, Delhi Sultanate 5th Edition, ASIN B007Q862WO, pp 156-158

- Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, pp 231-235, Oxford University Press

- "Eight Cities of Delhi: Tughlakabad". Delhi Tourism.

- Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, pp 236-242, Oxford University Press

- Elliot and Dowson, Táríkh-i Fíroz Sháhí of Ziauddin Barani, The History of India as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period (Vol 3), London, Trübner & Co

- Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, A History of India, (Routledge, 1986), 188.

- Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India by Jl Mehta p.97

- Chandra, Satish (1997). Medieval India: From Sultanate to the Mughals. New Delhi, India: Har-Anand Publications. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-8124105221.

- Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, pp 242-248, Oxford University Press

- Cornelius Walford (1878), The Famines of the World: Past and Present, p. 3, at Google Books, pp 9-10

- Judith Walsh, A Brief History of India, ISBN 978-0816083626, pp 70-72; Quote: "In 1335-42, during a severe famine and death in the Delhi region, the Sultanate offered no help to the starving residents."

- McKibben, William Jeffrey (1994). "The Monumental Pillars of Fīrūz Shāh Tughluq". Ars Orientalis. 24: 105–118. JSTOR 4629462.

- HM Elliot & John Dawson (1871), Tarikh I Firozi Shahi - Records of Court Historian Sams-i-Siraj The History of India as told by its own historians, Volume 3, Cornell University Archives, pp 352-353

- Prinsep, J (1837). "Interpretation of the most ancient of inscriptions on the pillar called lat of Feroz Shah, near Delhi, and of the Allahabad, Radhia and Mattiah pillar, or lat inscriptions which agree therewith". Journal of the Asiatic Society. 6 (2): 600–609.

- Firoz Shah Tughlak, Futuhat-i Firoz Shahi - Memoirs of Firoz Shah Tughlak, Translated in 1871 by Elliot and Dawson, Volume 3 - The History of India, Cornell University Archives

- Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, pp 249-251, Oxford University Press

- Firoz Shah Tughlak, Futuhat-i Firoz Shahi - Autobiographical memoirs, Translated in 1871 by Elliot and Dawson, Volume 3 - The History of India, Cornell University Archives, pp 377-381

- Annemarie Schimmel, Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, ISBN 978-9004061170, Brill Academic, pp 20-23

- Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, pp 248-254, Oxford University Press

- Peter Jackson (1999), The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History, Cambridge University Press, pp 312–317

- Beatrice F. Manz (2000). "Tīmūr Lang". In P. J. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C. E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W. P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. 10 (2 ed.). Brill.

- Lionel Trotter (1906), History of India: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day, Gorham Publishers London/New York, pp 74

- Annemarie Schimmel (1997), Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004061170, pp 36-37; Also see: Elliot, Studies in Indian History, 2nd Edition, pp 98-101

- Annemarie Schimmel, Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, ISBN 978-9004061170, Brill Academic, Chapter 2

- Ramananda Chatterjee (1961). The Modern Review. 109. Indiana University. p. 84.

- Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, pp 253-257, Oxford University Press

- Digby, S. (1975), The Tomb of Buhlūl Lōdī, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 38(03), pp 550-561

- "Delhi Sultanate under Lodhi Dynasty: A Complete Overview". Jagranjosh.com. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- Andrew Petersen, Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415060844, pp 7

- Richards, John (1965), The Economic History of the Lodi Period: 1451-1526, Journal de l'histoire economique et sociale de l'Orient, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp 47-67

- Lodi Dynasty Encyclopædia Britannica (2009)

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, pp. 379-380.

- Satish Chandra 2007, p. 105.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 379.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 385.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 384.

- Satish Chandra 2007, p. 102.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 380.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 389.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 383.

- Satish Chandra 2014, p. 105.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1992, p. 386.

- Architecture under the Sultanate of Delhi

- Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 85.

- Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 86.

- Hunter, W. W. (5 November 2013). The Indian Empire: Its People, History and Products. Routledge. p. 280. ISBN 9781136383014.

- Barua, Pradeep (2005). The State at War in South Asia. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 30, 317. ISBN 0803213441.

- Kishori Saran Lal 1950, p. 55.

- Hopkins, Steven Paul. "Singing the Body of God: The Hymns of Vedantadesika in Their South Indian Tradition". Oxford University Press. p. 69.

- Rummel, R. J. (31 December 2011). Death by Government. Transaction Publishers. p. 60. ISBN 9781412821292.

- Richard M. Eaton, Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States, Part II, Frontline, January 5, 2001, 70-77.

- Richard M. Eaton, Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States, Part I, Frontline, December 22, 2000, 62-70.

- Eaton, Richard M. (2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States" (PDF). The Hindu. Chennai, India. p. 297. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Annemarie Schimmel, Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, ISBN 978-9004061170, Brill Academic, pp 7-10

- James Brown (1949), The History of Islam in India, The Muslim World, 39(1), 11-25

- Eaton, Richard M. (December 2000). "Temple desecration in pre-modern India". Frontline. The Hindu Group. 17 (25).

- Eaton, Richard M. (September 2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States". Journal of Islamic Studies. 11 (3): 283–319. doi:10.1093/jis/11.3.283.

- Eaton, Richard M. (2004). Temple desecration and Muslim states in medieval India. Gurgaon: Hope India Publications. ISBN 978-8178710273.

- Welch, Anthony (1993), Architectural patronage and the past: The Tughluq sultans of India, Muqarnas, Vol. 10, 311-322

- Gul and Khan (2008), Growth and Development of Oriental Libraries in India, Library Philosophy and Practice, University of Nebrasaka-Lincoln

- Eva De Clercq (2010), ON JAINA APABHRAṂŚA PRAŚASTIS, Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 63 (3), pp 275–287

- R Islam (1997), A Note on the Position of the non-Muslim Subjects in the Sultanate of Delhi under the Khaljis and the Tughluqs, Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, 45, pp. 215–229; R Islam (2002), Theory and Practice of Jizyah in the Delhi Sultanate (14th Century), Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, 50, pp. 7–18

- A.L. Srivastava (1966), Delhi Sultanate, 5th Edition, Agra College

- Peter Jackson (2003), The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521543293, pp 287-295

- Firoz Shah Tughlak, Futuhat-i Firoz Shahi - Memoirs of Firoz Shah Tughlaq, Translated in 1871 by Elliot and Dawson, Volume 3 - The History of India, Cornell University Archives, pp 377-381

- Hasan Nizami et al, Taju-l Ma-asir & Appendix, Translated in 1871 by Elliot and Dawson, Volume 2 - The History of India, Cornell University Archives, pp 22, 219, 398, 471

- Richard Eaton, Temple desecration and Indo-Muslim states, Frontline (January 5, 2001), pp 72-73

- Ulugh Khan also known as Almas Beg was brother of Ala-al Din Khalji; his destruction campaign overlapped the two dynasties

- Somnath temple went through cycles of destruction by Sultans and rebuilding by Hindus

- Eaton (2000), Temple desecration in pre-modern India Frontline, p. 73, item 16 of the Table, Archived by Columbia University

- S. P. Udayakumar (1 January 2005). Presenting the Past: Anxious History and Ancient Future in Hindutva India. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-275-97209-7.

- History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D.; Radhey Shyam Chaurasia, Atlantic, 2009 [p191]

- Carl W. Ernst (2004). Eternal Garden: Mysticism, History, and Politics at a South Asian Sufi Center. Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-19-566869-8.

- Sarojini Chaturvedi (2006). A short history of South India. Saṁskṛiti. p. 209. ISBN 978-81-87374-37-4.

- Abraham Eraly (2015). The Age of Wrath: A History of the Delhi Sultanate. Penguin Books. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-93-5118-658-8.

- Kishori Saran Lal (1950). History of the Khaljis (1290-1320). Allahabad: The Indian Press. p. 84. OCLC 685167335.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burgess; Murray (1874). "The Rudra Mala at Siddhpur". Photographs of Architecture and Scenery in Gujarat and Rajputana. Bourne and Shepherd. p. 19. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- Robert Bradnock; Roma Bradnock (2000). India Handbook. McGraw-Hill. p. 959. ISBN 978-0-658-01151-1.

- Madison, Angus (6 December 2007). Contours of the world economy, 1–2030 AD: essays in macro-economic history. Oxford University Press. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-19-922720-4.

- Madison 2007, p. 376.

- Jos Gommans; Harriet Zurndorfer, eds. (2008). Roots and Routes of Development in China and India: Highlights of Fifty Years of The Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (1957-2007). Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV. p. 444. ISBN 978-90-04-17060-5.

- Pacey, Arnold (1991) [1990]. Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History (First MIT Press paperback ed.). Cambridge MA: The MIT Press. pp. 26–29.

- Siddiqui, Iqtidar Hussain (1986). "Water Works and Irrigation System in India during Pre-Mughal Times". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 29 (1): 63–64. doi:10.2307/3632072. JSTOR 3632072.

- Pacey 1991, p. 10.

- Oleson, John Peter (2000), "Water-Lifting", in Wikander, Örjan (ed.), Handbook of Ancient Water Technology, Technology and Change in History, 2, Leiden: Brill, pp. 217–302, ISBN 978-90-04-11123-3

- Pacey 1991, p. 36.

- Vinod Chanda Srivastava; Lallanji Gopal (2008). History of Agriculture in India, Up to C. 1200 A.D. New Delhi: Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy and Culture. ISBN 978-81-8069-521-6.

- Pacey 2000, p. 23-24.

- Smith, C. Wayne; Cothren, J. Tom (1999). Cotton: Origin, History, Technology, and Production. 4. John Wiley & Sons. pp. viii. ISBN 978-0471180456.

The first improvement in spinning technology was the spinning wheel, which was invented in India between 500 and 1000 A.D.

- Irfan Habib (2011), Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500, page 53, Pearson Education

- Harrison, Frederick. A Book about Books. London: John Murray, 1943. p. 79. Mandl, George. "Paper Chase: A Millennium in the Production and Use of Paper". Myers, Robin & Michael Harris (eds). A Millennium of the Book: Production, Design & Illustration in Manuscript & Print, 900–1900. Winchester: St. Paul’s Bibliographies, 1994. p. 182. Mann, George. Print: A Manual for Librarians and Students Describing in Detail the History, Methods, and Applications of Printing and Paper Making. London: Grafton & Co., 1952. p. 79. McMurtrie, Douglas C. The Book: The Story of Printing & Bookmaking. London: Oxford University Press, 1943. p. 63.

- Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985), Paper and Printing, Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Vol. 5 part 1, Cambridge University Press, pp. 2–3, 356–357

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012), Chinese History: A New Manual, Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute, p. 909

- D. C. Sircar (1996). Indian Epigraphy. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-81-208-1166-9.

- Habib 2011, p. 96.

- Habib 2011, p. 95-96.

- Angus Maddison (2001), The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective, pages 241-242, OECD Development Centre

- Angus Maddison (2001), The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective, page 236, OECD Development Centre

- Asher, C. B.; Talbot, C (1 January 2008), India Before Europe (1st ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 47, ISBN 978-0-521-51750-8

- Metcalf, B.; Metcalf, T. R. (9 October 2006), A Concise History of Modern India (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-521-68225-1

- Eaton, Richard M.'The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1993 1993, accessed on 1 May 2007

- Harle, 423-424

- Harle, 421, 425; Yale, 165; Blair & Bloom, 149

- Yale, 164-165; Harle, 423-424; Blair & Bloom, 149

- Also two huge minarets at Ghazni.

- Yale, 164; Harle, 424 (quoted); Blair & Bloom, 149

- Harle, 429

- Yale, 164 (quoted); Harle, 425

- Blair & Bloom, 149-150; Harle, 425

- Harle, 425

- Blair & Bloom, 151

- Blair & Bloom, 151-156; Harle, 425-426

- Blair & Bloom, 154; Harle, 425

- Blair & Bloom, 154-156

- Blair & Bloom, 154-156; Harle, 425

- Blair & Bloom, 149

- Blair & Bloom, 156

- Harle, 426; Blair & Bloom, 156

Bibliography

- Blair, Sheila, and Bloom, Jonathan M., The Art and Architecture of Islam, 1250-1800, 1995, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300064659

- Elliot, H. M. (Henry Miers), Sir; John Dowson (1867). "15. Táríkh-i Fíroz Sháhí, of Ziauddin Barani". The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period (Vol 3.). London: Trübner & Co.

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Srivastava, Ashirvadi Lal (1929). The Sultanate Of Delhi 711-1526 A D. Shiva Lal Agarwala & Company.

- Khan, Mohd. Adul Wali (1974). Gold and Silver Coins of Sultans of Delhi. Government of Andhra Pradesh.

- Kumar, Sunil. (2007). The Emergence of the Delhi Sultanate. Delhi: Permanent Black.

- Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Majumdar, R. C., Raychaudhuri, H., & Datta, K. (1951). An advanced history of India: 2. London: Macmillan.

- Majumdar, R. C., & Munshi, K. M. (1990). The Delhi Sultanate. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- "Yale":Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar and Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, 2001, Islamic Art and Architecture: 650-1250, Yale University Press, ISBN 9780300088694

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena (1992) [1970]. "The Khaljis: Alauddin Khalji". In Mohammad Habib and Khaliq Ahmad Nizami (ed.). A Comprehensive History of India: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206-1526). 5 (Second ed.). The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. OCLC 31870180.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Satish Chandra (2007). History of Medieval India: 800-1700. Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-3226-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Delhi Sultanate. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Delhi Sultanate |