Food

Food is any substance[1] consumed to provide nutritional support for an organism. Food is usually of plant or animal origin, and contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is ingested by an organism and assimilated by the organism's cells to provide energy, maintain life, or stimulate growth.

Historically, humans secured food through two methods: hunting and gathering and agriculture, which gave modern humans a mainly omnivorous diet. Worldwide, humanity has created numerous cuisines and culinary arts, including a wide array of ingredients, herbs, spices, techniques, and dishes.

Today, the majority of the food energy required by the ever-increasing population of the world is supplied by the food industry. Food safety and food security are monitored by agencies like the International Association for Food Protection, World Resources Institute, World Food Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization, and International Food Information Council. They address issues such as sustainability, biological diversity, climate change, nutritional economics, population growth, water supply, and access to food.

The right to food is a human right derived from the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), recognizing the "right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate food", as well as the "fundamental right to be free from hunger".

Food sources

Most food has its origin in plants. Some food is obtained directly from plants; but even animals that are used as food sources are raised by feeding them food derived from plants. Cereal grain is a staple food that provides more food energy worldwide than any other type of crop.[2] Corn (maize), wheat, and rice – in all of their varieties – account for 87% of all grain production worldwide.[3][4][5] Most of the grain that is produced worldwide is fed to livestock.

Some foods not from animal or plant sources include various edible fungi, especially mushrooms. Fungi and ambient bacteria are used in the preparation of fermented and pickled foods like leavened bread, alcoholic drinks, cheese, pickles, kombucha, and yogurt. Another example is blue-green algae such as Spirulina.[6] Inorganic substances such as salt, baking soda and cream of tartar are used to preserve or chemically alter an ingredient.

Plants

.jpg)

Many plants and plant parts are eaten as food and around 2,000 plant species are cultivated for food. Many of these plant species have several distinct cultivars.[7]

Seeds of plants are a good source of food for animals, including humans, because they contain the nutrients necessary for the plant's initial growth, including many healthful fats, such as omega fats. In fact, the majority of food consumed by human beings are seed-based foods. Edible seeds include cereals (corn, wheat, rice, et cetera), legumes (beans, peas, lentils, et cetera), and nuts. Oilseeds are often pressed to produce rich oils - sunflower, flaxseed, rapeseed (including canola oil), sesame, et cetera.[8]

Seeds are typically high in unsaturated fats and, in moderation, are considered a health food. However, not all seeds are edible. Large seeds, such as those from a lemon, pose a choking hazard, while seeds from cherries and apples contain cyanide which could be poisonous only if consumed in large volumes.[9]

Fruits are the ripened ovaries of plants, including the seeds within. Many plants and animals have coevolved such that the fruits of the former are an attractive food source to the latter, because animals that eat the fruits may excrete the seeds some distance away. Fruits, therefore, make up a significant part of the diets of most cultures. Some botanical fruits, such as tomatoes, pumpkins, and eggplants, are eaten as vegetables.[10] (For more information, see list of fruits.)

Vegetables are a second type of plant matter that is commonly eaten as food. These include root vegetables (potatoes and carrots), bulbs (onion family), leaf vegetables (spinach and lettuce), stem vegetables (bamboo shoots and asparagus), and inflorescence vegetables (globe artichokes and broccoli and other vegetables such as cabbage or cauliflower).[11]

Animals

Animals are used as food either directly or indirectly by the products they produce. Meat is an example of a direct product taken from an animal, which comes from muscle systems or from organs (offal).

Food products produced by animals include milk produced by mammary glands, which in many cultures is drunk or processed into dairy products (cheese, butter, etc.). In addition, birds and other animals lay eggs, which are often eaten, and bees produce honey, a reduced nectar from flowers, which is a popular sweetener in many cultures. Some cultures consume blood, sometimes in the form of blood sausage, as a thickener for sauces, or in a cured, salted form for times of food scarcity, and others use blood in stews such as jugged hare.[12]

Some cultures and people do not consume meat or animal food products for cultural, dietary, health, ethical, or ideological reasons. Vegetarians choose to forgo food from animal sources to varying degrees. Vegans do not consume any foods that are or contain ingredients from an animal source.

Classifications and types of food

- Broad classifications are covered below. For regional types, see Cuisine.

Adulterated food

Adulteration is a legal term meaning that a food product fails to meet the legal standards. One form of adulteration is an addition of another substance to a food item in order to increase the quantity of the food item in raw form or prepared form, which may result in the loss of actual quality of food item. These substances may be either available food items or non-food items. Among meat and meat products some of the items used to adulterate are water or ice, carcasses, or carcasses of animals other than the animal meant to be consumed.[13]

Camping food

Camping food includes ingredients used to prepare food suitable for backcountry camping and backpacking. The foods differ substantially from the ingredients found in a typical home kitchen. The primary differences relate to campers' and backpackers' special needs for foods that have appropriate cooking time, perishability, weight, and nutritional content.

To address these needs, camping food is often made up of either freeze-dried, precooked or dehydrated ingredients. Many campers use a combination of these foods.

Freeze-drying requires the use of heavy machinery and is not something that most campers are able to do on their own. Freeze-dried ingredients are often considered superior to dehydrated ingredients however because they rehydrate at camp faster and retain more flavor than their dehydrated counterparts. Freeze-dried ingredients take so little time to rehydrate that they can often be eaten without cooking them first and have a texture similar to a crunchy chip.

Dehydration can reduce the weight of the food by sixty to ninety percent by removing water through evaporation. Some foods dehydrate well, such as onions, peppers, and tomatoes.[14][15] Dehydration often produces a more compact, albeit slightly heavier, end result than freeze-drying.

Surplus precooked military Meals, Meals, Ready-to-Eat (MREs) are sometimes used by campers. These meals contain pre-cooked foods in retort pouches. A retort pouch is a plastic and metal foil laminate pouch that is used as an alternative to traditional industrial canning methods.

Diet food

Diet food (or "dietetic food") refers to any food or beverage whose recipe is altered to reduce fat, carbohydrates, abhor/adhore sugar in order to make it part of a weight loss program or diet. Such foods are usually intended to assist in weight loss or a change in body type, although bodybuilding supplements are designed to aid in gaining weight or muscle.

The process of making a diet version of a food usually requires finding an acceptable low-food-energy substitute for some high-food-energy ingredient.[16] This can be as simple as replacing some or all of the food's sugar with a sugar substitute as is common with diet soft drinks such as Coca-Cola (for example Diet Coke). In some snacks, the food may be baked instead of fried thus reducing the food energy. In other cases, low-fat ingredients may be used as replacements.

In whole grain foods, the higher fiber content effectively displaces some of the starch components of the flour. Since certain fibers have no food energy, this results in a modest energy reduction. Another technique relies on the intentional addition of other reduced-food-energy ingredients, such as resistant starch or dietary fiber, to replace part of the flour and achieve a more significant energy reduction.

Finger food

Finger food is food meant to be eaten directly using the hands, in contrast to food eaten with a knife and fork, spoon, chopsticks, or other utensils.[17] In some cultures, food is almost always eaten with the hands; for example, Ethiopian cuisine is eaten by rolling various dishes up in injera bread.[18] Foods considered street foods are frequently, though not exclusively, finger foods.

In the western world, finger foods are often either appetizers (hors d'œuvres) or entree/main course items. Examples of these are miniature meat pies, sausage rolls, sausages on sticks, cheese and olives on sticks, chicken drumsticks or wings, spring rolls, miniature quiches, samosas, sandwiches, Merenda or other such based foods, such as pitas or items in buns, bhajjis, potato wedges, vol au vents, several other such small items and risotto balls (arancini). Other well-known foods that are generally eaten with the hands include hamburgers, pizza, Chips, hot dogs, fruit and bread.

In East Asia, foods like pancakes or flatbreads (bing 饼) and street foods such as chuan (串, also pronounced chuan) are often eaten with the hands.

Fresh food

Fresh food is food which has not been preserved and has not spoiled yet. For vegetables and fruits, this means that they have been recently harvested and treated properly postharvest; for meat, it has recently been slaughtered and butchered; for fish, it has been recently caught or harvested and kept cold.

Dairy products are fresh and will spoil quickly. Thus, fresh cheese is cheese which has not been dried or salted for aging. Soured cream may be considered "fresh" (crème fraîche).

Fresh food has not been dried, smoked, salted, frozen, canned, pickled, or otherwise preserved.[19]

Frozen food

Freezing food preserves it from the time it is prepared to the time it is eaten. Since early times, farmers, fishermen, and trappers have preserved grains and produce in unheated buildings during the winter season.[20] Freezing food slows down decomposition by turning residual moisture into ice, inhibiting the growth of most bacterial species. In the food commodity industry, there are two processes: mechanical and cryogenic (or flash freezing). The kinetics of the freezing is important to preserve food quality and texture. Quicker freezing generates smaller ice crystals and maintains cellular structure. Cryogenic freezing is the quickest freezing technology available utilizing the extremely low temperature of liquid nitrogen −196 °C (−320 °F).[21]

Preserving food in domestic kitchens during modern times is achieved using household freezers. Accepted advice to householders was to freeze food on the day of purchase. An initiative by a supermarket group in 2012 (backed by the UK's Waste & Resources Action Programme) promotes the freezing of food "as soon as possible up to the product's 'use by' date". The Food Standards Agency was reported as supporting the change, providing the food had been stored correctly up to that time.[22]

Functional food

A functional food is a food given an additional function (often one related to health-promotion or disease prevention) by adding new ingredients or more of existing ingredients.[23] The term may also apply to traits purposely bred into existing edible plants, such as purple or gold potatoes having enriched anthocyanin or carotenoid contents, respectively.[24] Functional foods may be "designed to have physiological benefits and/or reduce the risk of chronic disease beyond basic nutritional functions, and may be similar in appearance to conventional food and consumed as part of a regular diet".[25]

The term was first used in Japan in the 1980s where there is a government approval process for functional foods called Foods for Specified Health Use (FOSHU).[26]

Health food

Health food is food marketed to provide human health effects beyond a normal healthy diet required for human nutrition. Foods marketed as health foods may be part of one or more categories, such as natural foods, organic foods, whole foods, vegetarian foods or dietary supplements. These products may be sold in health food stores or in the health food or organic sections of grocery stores.

Healthy food

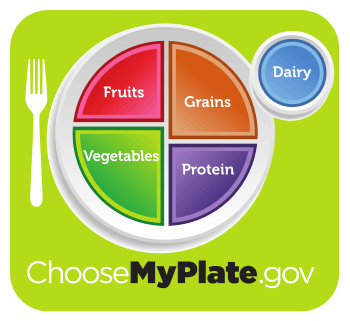

A healthy diet is a diet that helps to maintain or improve overall health. A healthy diet provides the body with essential nutrition: fluid, macronutrients, micronutrients, and adequate calories.[27][28]

For people who are healthy, a healthy diet is not complicated and contains mostly fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and includes little to no processed food and sweetened beverages. The requirements for a healthy diet can be met from a variety of plant-based and animal-based foods, although a non-animal source of vitamin B12 is needed for those following a vegan diet.[29] Various nutrition guides are published by medical and governmental institutions to educate individuals on what they should be eating to be healthy. Nutrition facts labels are also mandatory in some countries to allow consumers to choose between foods based on the components relevant to health.[30]

A healthy lifestyle includes getting exercise every day along with eating a healthy diet. A healthy lifestyle may lower disease risks, such as obesity, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension and cancer.[27][31]

There are specialized healthy diets, called medical nutrition therapy, for people with various diseases or conditions. There are also prescientific ideas about such specialized diets, as in dietary therapy in traditional Chinese medicine.

The World Health Organization (WHO) makes the following 5 recommendations with respect to both populations and individuals:[32]

- Maintain a healthy weight by eating roughly the same number of calories that your body is using.

- Limit intake of fats. Not more than 30% of the total calories should come from fats. Prefer unsaturated fats to saturated fats. Avoid trans fats.

- Eat at least 400 grams of fruits and vegetables per day (potatoes, sweet potatoes, cassava and other starchy roots do not count). A healthy diet also contains legumes (e.g. lentils, beans), whole grains and nuts.

- Limit the intake of simple sugars to less than 10% of calorie (below 5% of calories or 25 grams may be even better)[33]

- Limit salt / sodium from all sources and ensure that salt is iodized. Less than 5 grams of salt per day can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.[34]

Live food

Live food is living food for carnivorous or omnivorous animals kept in captivity; in other words, small animals such as insects or mice fed to larger carnivorous or omnivorous species kept either in a zoo or as a pet.

Live food is commonly used as feed for a variety of species of exotic pets and zoo animals, ranging from alligators to various snakes, frogs and lizards, but also including other, non-reptile, non-amphibian carnivores and omnivores (for instance, skunks, which are omnivorous mammals, can technically be fed a limited amount of live food, though this is not a common practice). Common live food ranges from crickets (used as an inexpensive form of feed for carnivorous and omnivorous reptiles such as bearded dragons and commonly available in pet stores for this reason), waxworms, mealworms and to a lesser extent cockroaches and locusts, to small birds and mammals such as mice or chickens.

Medical food

Medical foods are foods that are specially formulated and intended for the dietary management of a disease that has distinctive nutritional needs that cannot be met by normal diet alone. In the United States they were defined in the Food and Drug Administration's 1988 Orphan Drug Act Amendments[35] and are subject to the general food and safety labeling requirements of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. In Europe the European Food Safety Authority established definitions for "foods for special medical purposes" (FSMPs) in 2015.[36]

Medical foods, called "food for special medical purposes" in Europe,[37] are distinct from the broader category of foods for special dietary use, from traditional foods that bear a health claim, and from dietary supplements. In order to be considered a medical food the product must, at a minimum:[38][39]

- be a food for oral ingestion or tube feeding (nasogastric tube)

- be labeled for the dietary management of a specific medical disorder, disease or condition for which there are distinctive nutritional requirements, and

- be intended to be used under medical supervision.

Medical foods can be classified into the following categories:

- Nutritionally complete formulas

- Nutritionally incomplete formulas

- Formulas for metabolic disorders

- Oral rehydration products

Natural foods

Natural foods and "all-natural foods" are widely used terms in food labeling and marketing with a variety of definitions, most of which are vague. The term is often assumed to imply foods that are not processed and whose ingredients are all natural products (in the chemist's sense of that term), thus conveying an appeal to nature. But the lack of standards in most jurisdictions means that the term assures nothing. In some countries, the term "natural" is defined and enforced. In others, such as the United States, it is not enforced.

“Natural foods” are often assumed to be foods that are not processed, or do not contain any food additives, or do not contain particular additives such as hormones, antibiotics, sweeteners, food colors, or flavorings that were not originally in the food.[40] In fact, many people (63%) when surveyed showed a preference for products labeled "natural" compared to the unmarked counterparts, based on the common belief (86% of polled consumers) that the term "natural" indicated that the food does not contain any artificial ingredients.[41] The terms are variously used and misused on labels and in advertisements.[42]

The international Food and Agriculture Organization’s Codex Alimentarius does not recognize the term “natural” but does have a standard for organic foods.[43]

Negative-calorie food

A negative-calorie food is food that supposedly requires more food energy to be digested than the food provides. Its thermic effect or specific dynamic action – the caloric "cost" of digesting the food – would be greater than its food energy content. Despite its recurring popularity in dieting guides, there is no scientific evidence supporting the idea that any food is calorically negative. While some chilled beverages are calorically negative, the effect is minimal[44] and drinking large amounts of water can be dangerous.

Organic food

Organic food is food produced by methods that comply with the standards of organic farming. Standards vary worldwide, but organic farming in general features practices that strive to cycle resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity. Organizations regulating organic products may restrict the use of certain pesticides and fertilizers in farming. In general, organic foods are also usually not processed using irradiation, industrial solvents or synthetic food additives.[45]

Currently, the European Union, the United States, Canada, Mexico, Japan, and many other countries require producers to obtain special certification in order to market food as organic within their borders. In the context of these regulations, organic food is produced in a way that complies with organic standards set by regional organizations, national governments, and international organizations. Although the produce of kitchen gardens may be organic, selling food with an organic label is regulated by governmental food safety authorities, such as the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) or European Commission (EC).[46]

Fertilizing and the use of pesticides in conventional farming has caused, and is causing, enormous damage worldwide to local ecosystems, biodiversity, groundwater and drinking water supplies, and sometimes farmer health and fertility. These environmental, economic and health issues are intended to be minimized or avoided in organic farming. From a consumers perspective, there is not sufficient evidence in scientific and medical literature to support claims that organic food is safer or healthier to eat than conventionally grown food. While there may be some differences in the nutrient and antinutrient contents of organically- and conventionally-produced food, the variable nature of food production and handling makes it difficult to generalize results.[47][48][49][50][51] Claims that organic food tastes better are generally not supported by tests.[48][52]

Peasant foods

Peasant foods are dishes specific to a particular culture, made from accessible and inexpensive ingredients, and usually prepared and seasoned to make them more palatable. They often form a significant part of the diets of people who live in poverty, or have a lower income compared to the average for their society or country.

Peasant foods have been described as being the diet of peasants, that is, tenant or poorer farmers and their farm workers,[53] and by extension, of other cash-poor people. They may use ingredients, such as offal and less-tender cuts of meat, which are not as marketable as a cash crop. Characteristic recipes often consist of hearty one-dish meals, in which chunks of meat and various vegetables are eaten in a savory broth, with bread or other staple food. Sausages are also amenable to varied readily available ingredients, and they themselves tend to contain offal and grains.

Peasant foods often involve skilled preparation by knowledgeable cooks using inventiveness and skills passed down from earlier generations. Such dishes are often prized as ethnic foods by other cultures and by descendants of the native culture who still desire these traditional dishes.

Prison food

Prison food is the term for meals served to prisoners while incarcerated in correctional institutions. While some prisons prepare their own food, many use staff from on-site catering companies. Many prisons today support the requirements of specific religions, as well as vegetarianism.[54] It is said that prison food of many developed countries is adequate to maintain health and dieting.[55]

Seasonal food

"Seasonal" here refers to the times of the year when the harvest or the flavor of a given type of food is at its peak. This is usually the time when the item is harvested, with some exceptions; an example being sweet potatoes which are best eaten quite a while after harvest. It also appeals to people who prefer a low carbon diet that reduces the greenhouse gas emissions resulting from food consumption (Food miles).

Shelf-stable food

Shelf-stable food (sometimes ambient food) is food of a type that can be safely stored at room temperature in a sealed container. This includes foods that would normally be stored refrigerated but which have been processed so that they can be safely stored at room or ambient temperature for a usefully long shelf life.

Various food preservation and packaging techniques are used to extend a food's shelf life. Decreasing the amount of available water in a product, increasing its acidity, or irradiating[56] or otherwise sterilizing the food and then sealing it in an air-tight container are all ways of depriving bacteria of suitable conditions in which to thrive. All of these approaches can all extend a food's shelf life without unacceptably changing its taste or texture.

For some foods, alternative ingredients can be used. Common oils and fats become rancid relatively quickly if not refrigerated; replacing them with hydrogenated oils delays the onset of rancidity, increasing shelf life. This is a common approach in industrial food production, but recent concerns about health hazards associated with trans fats have led to their strict control in several jurisdictions.[57] Even where trans fats are not prohibited, in many places there are new labeling laws (or rules), which require information to be printed on packages, or to be published elsewhere, about the amount of trans fat contained in certain products.

Space food

Space food is a type of food product created and processed for consumption by astronauts in outer space. The food has specific requirements of providing balanced nutrition for individuals working in space while being easy and safe to store, prepare and consume in the machinery-filled weightless environments of crewed spacecraft.

In recent years, space food has been used by various nations engaging in space programs as a way to share and show off their cultural identity and facilitate intercultural communication. Although astronauts consume a wide variety of foods and beverages in space, the initial idea from The Man in Space Committee of the Space Science Board in 1963 was to supply astronauts with a formula diet that would supply all the needed vitamins and nutrients.[58]

Traditional food

Traditional foods are foods and dishes that are passed through generations[59] or which have been consumed many generations.[60] Traditional foods and dishes are traditional in nature, and may have a historic precedent in a national dish, regional cuisine[59] or local cuisine. Traditional foods and beverages may be produced as homemade, by restaurants and small manufacturers, and by large food processing plant facilities.[61]

Some traditional foods have geographical indications and traditional specialities in the European Union designations per European Union schemes of geographical indications and traditional specialties: Protected designation of origin (PDO), Protected geographical indication (PGI) and Traditional specialities guaranteed (TSG). These standards serve to promote and protect names of quality agricultural products and foodstuffs.[62]

This article also includes information about traditional beverages.

Whole food

Whole foods are plant foods that are unprocessed and unrefined, or processed and refined as little as possible, before being consumed.[63] Examples of whole foods include whole grains, tubers, legumes, fruits, vegetables.[64]

There is some confusion over the usage of the term surrounding the inclusion of certain foods, in particular animal foods. The modern usage of the term whole foods diet is now widely synonymous with "whole foods plant-based diet" with animal products, oil and salt no longer constituting whole foods.[65]

The earliest use of the term in the post-industrial age appears to be in 1946 in The Farmer, a quarterly magazine published and edited from his farm by F. Newman Turner, a writer and pioneering organic farmer. The magazine sponsored the establishment of the Producer-Consumer Whole Food Society Ltd, with Newman Turner as president and Derek Randal as vice-president.[66] Whole food was defined as "mature produce of field, orchard, or garden without subtraction, addition, or alteration grown from seed without chemical dressing, in fertile soil manured solely with animal and vegetable wastes, and composts therefrom, and ground, raw rock and without chemical manures, sprays, or insecticides," having intent to connect suppliers and the growing public demand for such food.[66] Such diets are rich in whole and unrefined foods, like whole grains, dark green and yellow/orange-fleshed vegetables and fruits, legumes, nuts and seeds.[63]

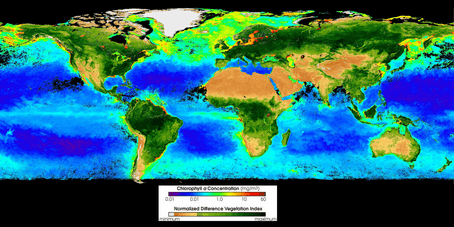

Production

.jpg)

Most food has always been obtained through agriculture. With increasing concern over both the methods and products of modern industrial agriculture, there has been a growing trend toward sustainable agricultural practices. This approach, partly fueled by consumer demand, encourages biodiversity, local self-reliance and organic farming methods.[67] Major influences on food production include international organizations (e.g. the World Trade Organization and Common Agricultural Policy), national government policy (or law), and war.[68]

Several organisations have begun calling for a new kind of agriculture in which agroecosystems provide food but also support vital ecosystem services so that soil fertility and biodiversity are maintained rather than compromised. According to the International Water Management Institute and UNEP, well-managed agroecosystems not only provide food, fiber and animal products, they also provide services such as flood mitigation, groundwater recharge, erosion control and habitats for plants, birds, fish and other animals.[69]

Taste perception

Animals, specifically humans, have five different types of tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. As animals have evolved, the tastes that provide the most energy (sugar and fats) are the most pleasant to eat while others, such as bitter, are not enjoyable.[70] Water, while important for survival, has no taste.[71] Fats, on the other hand, especially saturated fats, are thicker and rich and are thus considered more enjoyable to eat.

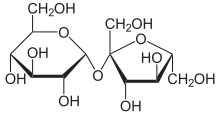

Sweet

Generally regarded as the most pleasant taste, sweetness is almost always caused by a type of simple sugar such as glucose or fructose, or disaccharides such as sucrose, a molecule combining glucose and fructose.[72] Complex carbohydrates are long chains and thus do not have the sweet taste. Artificial sweeteners such as sucralose are used to mimic the sugar molecule, creating the sensation of sweet, without the calories. Other types of sugar include raw sugar, which is known for its amber color, as it is unprocessed. As sugar is vital for energy and survival, the taste of sugar is pleasant.

The stevia plant contains a compound known as steviol which, when extracted, has 300 times the sweetness of sugar while having minimal impact on blood sugar.[73]

Sour

Sourness is caused by the taste of acids, such as vinegar in alcoholic beverages. Sour foods include citrus, specifically lemons, limes, and to a lesser degree oranges. Sour is evolutionarily significant as it is a sign for a food that may have gone rancid due to bacteria.[74] Many foods, however, are slightly acidic, and help stimulate the taste buds and enhance flavor.

Salty

Saltiness is the taste of alkali metal ions such as sodium and potassium. It is found in almost every food in low to moderate proportions to enhance flavor, although to eat pure salt is regarded as highly unpleasant. There are many different types of salt, with each having a different degree of saltiness, including sea salt, fleur de sel, kosher salt, mined salt, and grey salt. Other than enhancing flavor, its significance is that the body needs and maintains a delicate electrolyte balance, which is the kidney's function. Salt may be iodized, meaning iodine has been added to it, a necessary nutrient that promotes thyroid function. Some canned foods, notably soups or packaged broths, tend to be high in salt as a means of preserving the food longer. Historically salt has long been used as a meat preservative as salt promotes water excretion. Similarly, dried foods also promote food safety.[75]

Bitter

Bitterness is a sensation often considered unpleasant characterized by having a sharp, pungent taste. Unsweetened dark chocolate, caffeine, lemon rind, and some types of fruit are known to be bitter.

Umami

Umami, the Japanese word for delicious, is the least known in Western popular culture but has a long tradition in Asian cuisine. Umami is the taste of glutamates, especially monosodium glutamate (MSG).[72] It is characterized as savory, meaty, and rich in flavor.[76] Salmon and mushrooms are foods high in umami.[77]

Cuisine

Many scholars claim that the rhetorical function of food is to represent the culture of a country, and that it can be used as a form of communication. According to Goode, Curtis and Theophano, food "is the last aspect of an ethnic culture to be lost".[78]

Many cultures have a recognizable cuisine, a specific set of cooking traditions using various spices or a combination of flavors unique to that culture, which evolves over time. Other differences include preferences (hot or cold, spicy, etc.) and practices, the study of which is known as gastronomy. Many cultures have diversified their foods by means of preparation, cooking methods, and manufacturing. This also includes a complex food trade which helps the cultures to economically survive by way of food, not just by consumption.

Some popular types of ethnic foods include Italian, French, Japanese, Chinese, American, Cajun, Thai, African, Indian and Nepalese. Various cultures throughout the world study the dietary analysis of food habits. While evolutionarily speaking, as opposed to culturally, humans are omnivores, religion and social constructs such as morality, activism, or environmentalism will often affect which foods they will consume. Food is eaten and typically enjoyed through the sense of taste, the perception of flavor from eating and drinking. Certain tastes are more enjoyable than others, for evolutionary purposes.

Presentation

Aesthetically pleasing and eye-appealing food presentations can encourage people to consume foods. A common saying is that people "eat with their eyes". Food presented in a clean and appetizing way will encourage a good flavor, even if unsatisfactory.[79][80]

Contrast in texture

Texture plays a crucial role in the enjoyment of eating foods. Contrasts in textures, such as something crunchy in an otherwise smooth dish, may increase the appeal of eating it. Common examples include adding granola to yogurt, adding croutons to a salad or soup, and toasting bread to enhance its crunchiness for a smooth topping, such as jam or butter.[81]

Contrast in taste

Another universal phenomenon regarding food is the appeal of contrast in taste and presentation. For example, such opposite flavors as sweetness and saltiness tend to go well together, as in kettle corn and nuts.

Food preparation

While many foods can be eaten raw, many also undergo some form of preparation for reasons of safety, palatability, texture, or flavor. At the simplest level this may involve washing, cutting, trimming, or adding other foods or ingredients, such as spices. It may also involve mixing, heating or cooling, pressure cooking, fermentation, or combination with other food. In a home, most food preparation takes place in a kitchen. Some preparation is done to enhance the taste or aesthetic appeal; other preparation may help to preserve the food; others may be involved in cultural identity. A meal is made up of food which is prepared to be eaten at a specific time and place.[82]

Animal preparation

The preparation of animal-based food usually involves slaughter, evisceration, hanging, portioning, and rendering. In developed countries, this is usually done outside the home in slaughterhouses, which are used to process animals en masse for meat production. Many countries regulate their slaughterhouses by law. For example, the United States has established the Humane Slaughter Act of 1958, which requires that an animal be stunned before killing. This act, like those in many countries, exempts slaughter in accordance with religious law, such as kosher, shechita, and dhabīḥah halal. Strict interpretations of kashrut require the animal to be fully aware when its carotid artery is cut.[83]

On the local level, a butcher may commonly break down larger animal meat into smaller manageable cuts, and pre-wrap them for commercial sale or wrap them to order in butcher paper. In addition, fish and seafood may be fabricated into smaller cuts by a fishmonger. However, fish butchery may be done onboard a fishing vessel and quick-frozen for the preservation of quality.[84]

Cooking

The term "cooking" encompasses a vast range of methods, tools, and combinations of ingredients to improve the flavor or digestibility of food. Cooking technique, known as culinary art, generally requires the selection, measurement, and combining of ingredients in an ordered procedure in an effort to achieve the desired result. Constraints on success include the variability of ingredients, ambient conditions, tools, and the skill of the individual cook.[85] The diversity of cooking worldwide is a reflection of the myriad nutritional, aesthetic, agricultural, economic, cultural, and religious considerations that affect it.[86]

Cooking requires applying heat to a food which usually, though not always, chemically changes the molecules, thus changing its flavor, texture, appearance, and nutritional properties.[87] Cooking certain proteins, such as egg whites, meats, and fish, denatures the protein, causing it to firm. There is archaeological evidence of roasted foodstuffs at Homo erectus campsites dating from 420,000 years ago.[88] Boiling as a means of cooking requires a container, and has been practiced at least since the 10th millennium BC with the introduction of pottery.[89]

Cooking equipment

There are many different types of equipment used for cooking.

Ovens are mostly hollow devices that get very hot (up to 500 °F (260 °C)) and are used for baking or roasting and offer a dry-heat cooking method. Different cuisines will use different types of ovens. For example, Indian culture uses a tandoor oven, which is a cylindrical clay oven which operates at a single high temperature.[90] Western kitchens use variable temperature convection ovens, conventional ovens, toaster ovens, or non-radiant heat ovens like the microwave oven. Classic Italian cuisine includes the use of a brick oven containing burning wood. Ovens may be wood-fired, coal-fired, gas, electric, or oil-fired.[91]

Various types of cook-tops are used as well. They carry the same variations of fuel types as the ovens mentioned above. Cook-tops are used to heat vessels placed on top of the heat source, such as a sauté pan, sauce pot, frying pan, or pressure cooker. These pieces of equipment can use either a moist or dry cooking method and include methods such as steaming, simmering, boiling, and poaching for moist methods, while the dry methods include sautéing, pan frying, and deep-frying.[92]

In addition, many cultures use grills for cooking. A grill operates with a radiant heat source from below, usually covered with a metal grid and sometimes a cover. An open-pit barbecue in the American south is one example along with the American style outdoor grill fueled by wood, liquid propane, or charcoal along with soaked wood chips for smoking.[93] A Mexican style of barbecue is called barbacoa, which involves the cooking of meats such as whole sheep over an open fire. In Argentina, an asado (Spanish for "grilled") is prepared on a grill held over an open pit or fire made upon the ground, on which a whole animal or smaller cuts are grilled.[94]

Raw food preparation

Certain cultures highlight animal and vegetable foods in a raw state. Salads consisting of raw vegetables or fruits are common in many cuisines. Sashimi in Japanese cuisine consists of raw sliced fish or other meat, and sushi often incorporates raw fish or seafood. Steak tartare and salmon tartare are dishes made from diced or ground raw beef or salmon, mixed with various ingredients and served with baguettes, brioche, or frites.[95] In Italy, carpaccio is a dish of very thinly sliced raw beef, drizzled with a vinaigrette made with olive oil.[96] The health food movement known as raw foodism promotes a mostly vegan diet of raw fruits, vegetables, and grains prepared in various ways, including juicing, food dehydration, sprouting, and other methods of preparation that do not heat the food above 118 °F (47.8 °C).[97] An example of a raw meat dish is ceviche, a Latin American dish made with raw meat that is "cooked" from the highly acidic citric juice from lemons and limes along with other aromatics such as garlic.

Restaurants

.jpg)

Restaurants employ chefs to prepare the food, and waiters to serve customers at the table.[98] The term restaurant comes from an old term for a restorative meat broth; this broth (or bouillon) was served in elegant outlets in Paris from the mid 18th century.[99][100] These refined "restaurants" were a marked change from the usual basic eateries such as inns and taverns,[100] and some had developed from early Parisian cafés, such as Café Procope, by first serving bouillon, then adding other cooked food to their menus.[101]

Commercial eateries existed during the Roman period, with evidence of 150 "thermopolia", a form of fast food restaurant, found in Pompeii,[102] and urban sales of prepared foods may have existed in China during the Song dynasty.[103]

In 2005, the population of the United States spent $496 billion on out-of-home dining. Expenditures by type of out-of-home dining were as follows: 40% in full-service restaurants, 37.2% in limited service restaurants (fast food), 6.6% in schools or colleges, 5.4% in bars and vending machines, 4.7% in hotels and motels, 4.0% in recreational places, and 2.2% in others, which includes military bases.[104]

Food manufacturing

.jpg)

Packaged foods are manufactured outside the home for purchase. This can be as simple as a butcher preparing meat, or as complex as a modern international food industry. Early food processing techniques were limited by available food preservation, packaging, and transportation. This mainly involved salting, curing, curdling, drying, pickling, fermenting, and smoking.[105] Food manufacturing arose during the industrial revolution in the 19th century.[106] This development took advantage of new mass markets and emerging technology, such as milling, preservation, packaging and labeling, and transportation. It brought the advantages of pre-prepared time-saving food to the bulk of ordinary people who did not employ domestic servants.[107]

At the start of the 21st century, a two-tier structure has arisen, with a few international food processing giants controlling a wide range of well-known food brands. There also exists a wide array of small local or national food processing companies.[108] Advanced technologies have also come to change food manufacture. Computer-based control systems, sophisticated processing and packaging methods, and logistics and distribution advances can enhance product quality, improve food safety, and reduce costs.[107]

Commercial trade

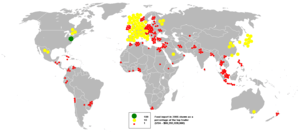

International food imports and exports

The World Bank reported that the European Union was the top food importer in 2005, followed at a distance by the US and Japan. Britain's need for food was especially well-illustrated in World War II. Despite the implementation of food rationing, Britain remained dependent on food imports and the result was a long term engagement in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Food is traded and marketed on a global basis. The variety and availability of food is no longer restricted by the diversity of locally grown food or the limitations of the local growing season.[109] Between 1961 and 1999, there was a 400% increase in worldwide food exports.[110] Some countries are now economically dependent on food exports, which in some cases account for over 80% of all exports.[111]

In 1994, over 100 countries became signatories to the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in a dramatic increase in trade liberalization. This included an agreement to reduce subsidies paid to farmers, underpinned by the WTO enforcement of agricultural subsidy, tariffs, import quotas, and settlement of trade disputes that cannot be bilaterally resolved.[112] Where trade barriers are raised on the disputed grounds of public health and safety, the WTO refer the dispute to the Codex Alimentarius Commission, which was founded in 1962 by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization. Trade liberalization has greatly affected world food trade.[113]

Marketing and retailing

Food marketing brings together the producer and the consumer. The marketing of even a single food product can be a complicated process involving many producers and companies. For example, fifty-six companies are involved in making one can of chicken noodle soup. These businesses include not only chicken and vegetable processors but also the companies that transport the ingredients and those who print labels and manufacture cans.[114] The food marketing system is the largest direct and indirect non-government employer in the United States.

In the pre-modern era, the sale of surplus food took place once a week when farmers took their wares on market day into the local village marketplace. Here food was sold to grocers for sale in their local shops for purchase by local consumers.[86][107] With the onset of industrialization and the development of the food processing industry, a wider range of food could be sold and distributed in distant locations. Typically early grocery shops would be counter-based shops, in which purchasers told the shop-keeper what they wanted, so that the shop-keeper could get it for them.[86][115]

In the 20th century, supermarkets were born. Supermarkets brought with them a self service approach to shopping using shopping carts, and were able to offer quality food at lower cost through economies of scale and reduced staffing costs. In the latter part of the 20th century, this has been further revolutionized by the development of vast warehouse-sized, out-of-town supermarkets, selling a wide range of food from around the world.[116]

Unlike food processors, food retailing is a two-tier market in which a small number of very large companies control a large proportion of supermarkets. The supermarket giants wield great purchasing power over farmers and processors, and strong influence over consumers. Nevertheless, less than 10% of consumer spending on food goes to farmers, with larger percentages going to advertising, transportation, and intermediate corporations.[117]

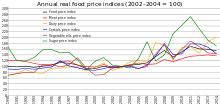

Prices

It is rare for price spikes to hit all major foods in most countries at once, but food prices suffered all-time peaks in 2008 and 2011, posting a 15% and 12% deflated increase year-over-year, representing prices higher than any data collected.[119] One reason for the increase in food prices may be the increase in oil prices at the same time.[120][121]

In December 2007, 37 countries faced food crises, and 20 had imposed some sort of food-price controls. In China, the price of pork jumped 58% in 2007. In the 1980s and 1990s, farm subsidies and support programs allowed major grain exporting countries to hold large surpluses, which could be tapped during food shortages to keep prices down. However, new trade policies had made agricultural production much more responsive to market demands, putting global food reserves at their lowest since 1983.[122]

Rising food prices in those years have been linked with social unrest around the world, including rioting in Bangladesh and Mexico,[123] and the Arab Spring.[124] Food prices worldwide increased in 2008.[125][126] One cause of rising food prices is wealthier Asian consumers are westernizing their diets, and farmers and nations of the third world are struggling to keep up the pace. The past five years have seen rapid growth in the contribution of Asian nations to the global fluid and powdered milk manufacturing industry, which in 2008 accounted for more than 30% of production, while China alone accounts for more than 10% of both production and consumption in the global fruit and vegetable processing and preserving industry.[127]

In 2013 Overseas Development Institute researchers showed that rice has more than doubled in price since 2000, rising by 120% in real terms. This was as a result of shifts in trade policy and restocking by major producers. More fundamental drivers of increased prices are the higher costs of fertilizer, diesel, and labor. Parts of Asia see rural wages rise with potential large benefits for the 1.3 billion (2008 estimate) of Asia's poor in reducing the poverty they face. However, this negatively impacts more vulnerable groups who don't share in the economic boom, especially in Asian and African coastal cities. The researchers said the threat means social-protection policies are needed to guard against price shocks. The research proposed that in the longer run, the rises present opportunities to export for Western African farmers with high potential for rice production to replace imports with domestic production.[128]

Most recently, global food prices have been more stable and relatively low, after a sizable increase in late 2017, they are back under 75% of the nominal value seen during the all-time high in the 2011 food crisis.

As investment

Institutions such as hedge funds, pension funds and investment banks like Barclays Capital, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley[123] have been instrumental in pushing up prices in the last five years, with investment in food commodities rising from $65bn to $126bn (£41bn to £79bn) between 2007 and 2012, contributing to 30-year highs. This has caused price fluctuations which are not strongly related to the actual supply of food, according to the United Nations.[123] Financial institutions now make up 61% of all investment in wheat futures. According to Olivier De Schutter, the UN special rapporteur on food, there was a rush by institutions to enter the food market following George W. Bush's Commodities Futures Modernization Act of 2000.[123] De Schutter told the Independent in March 2012: "What we are seeing now is that these financial markets have developed massively with the arrival of these new financial investors, who are purely interested in the short-term monetary gain and are not really interested in the physical thing – they never actually buy the ton of wheat or maize; they only buy a promise to buy or to sell. The result of this financialization of the commodities market is that the prices of the products respond increasingly to a purely speculative logic. This explains why in very short periods of time we see prices spiking or bubbles exploding because prices are less and less determined by the real match between supply and demand."[123] In 2011, 450 economists from around the world called on the G20 to regulate the commodities market more.[123]

Some experts have said that speculation has merely aggravated other factors, such as climate change, competition with bio-fuels and overall rising demand.[123] However, some such as Jayati Ghosh, professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, have pointed out that prices have increased irrespective of supply and demand issues: Ghosh points to world wheat prices, which doubled in the period from June to December 2010, despite there being no fall in global supply.[123]

Famine and hunger

Food deprivation leads to malnutrition and ultimately starvation. This is often connected with famine, which involves the absence of food in entire communities. This can have a devastating and widespread effect on human health and mortality. Rationing is sometimes used to distribute food in times of shortage, most notably during times of war.[68]

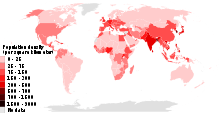

Starvation is a significant international problem. Approximately 815 million people are undernourished, and over 16,000 children die per day from hunger-related causes.[129] Food deprivation is regarded as a deficit need in Maslow's hierarchy of needs and is measured using famine scales.[130]

Food aid

Food aid can benefit people suffering from a shortage of food. It can be used to improve peoples' lives in the short term, so that a society can increase its standard of living to the point that food aid is no longer required.[131] Conversely, badly managed food aid can create problems by disrupting local markets, depressing crop prices, and discouraging food production. Sometimes a cycle of food aid dependence can develop.[132] Its provision, or threatened withdrawal, is sometimes used as a political tool to influence the policies of the destination country, a strategy known as food politics. Sometimes, food aid provisions will require certain types of food be purchased from certain sellers, and food aid can be misused to enhance the markets of donor countries.[133] International efforts to distribute food to the neediest countries are often coordinated by the World Food Programme.[134]

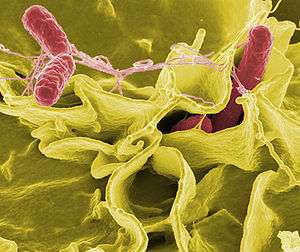

Safety

Foodborne illness, commonly called "food poisoning", is caused by bacteria, toxins, viruses, parasites, and prions. Roughly 7 million people die of food poisoning each year, with about 10 times as many suffering from a non-fatal version.[135] The two most common factors leading to cases of bacterial foodborne illness are cross-contamination of ready-to-eat food from other uncooked foods and improper temperature control. Less commonly, acute adverse reactions can also occur if chemical contamination of food occurs, for example from improper storage, or use of non-food grade soaps and disinfectants. Food can also be adulterated by a very wide range of articles (known as "foreign bodies") during farming, manufacture, cooking, packaging, distribution, or sale. These foreign bodies can include pests or their droppings, hairs, cigarette butts, wood chips, and all manner of other contaminants. It is possible for certain types of food to become contaminated if stored or presented in an unsafe container, such as a ceramic pot with lead-based glaze.[135]

Food poisoning has been recognized as a disease since as early as Hippocrates.[136] The sale of rancid, contaminated, or adulterated food was commonplace until the introduction of hygiene, refrigeration, and vermin controls in the 19th century. Discovery of techniques for killing bacteria using heat, and other microbiological studies by scientists such as Louis Pasteur, contributed to the modern sanitation standards that are ubiquitous in developed nations today. This was further underpinned by the work of Justus von Liebig, which led to the development of modern food storage and food preservation methods.[137] In more recent years, a greater understanding of the causes of food-borne illnesses has led to the development of more systematic approaches such as the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP), which can identify and eliminate many risks.[138]

Recommended measures for ensuring food safety include maintaining a clean preparation area with foods of different types kept separate, ensuring an adequate cooking temperature, and refrigerating foods promptly after cooking.[139]

Foods that spoil easily, such as meats, dairy, and seafood, must be prepared a certain way to avoid contaminating the people for whom they are prepared. As such, the rule of thumb is that cold foods (such as dairy products) should be kept cold and hot foods (such as soup) should be kept hot until storage. Cold meats, such as chicken, that are to be cooked should not be placed at room temperature for thawing, at the risk of dangerous bacterial growth, such as Salmonella or E. coli.[140]

Allergies

Some people have allergies or sensitivities to foods that are not problematic to most people. This occurs when a person's immune system mistakes a certain food protein for a harmful foreign agent and attacks it. About 2% of adults and 8% of children have a food allergy.[141] The amount of the food substance required to provoke a reaction in a particularly susceptible individual can be quite small. In some instances, traces of food in the air, too minute to be perceived through smell, have been known to provoke lethal reactions in extremely sensitive individuals. Common food allergens are gluten, corn, shellfish (mollusks), peanuts, and soy.[141] Allergens frequently produce symptoms such as diarrhea, rashes, bloating, vomiting, and regurgitation. The digestive complaints usually develop within half an hour of ingesting the allergen.[141]

Rarely, food allergies can lead to a medical emergency, such as anaphylactic shock, hypotension (low blood pressure), and loss of consciousness. An allergen associated with this type of reaction is peanut, although latex products can induce similar reactions.[141] Initial treatment is with epinephrine (adrenaline), often carried by known patients in the form of an Epi-pen or Twinject.[142][143]

Other health issues

Human diet was estimated to cause perhaps around 35% of cancers in a human epidemiological analysis by Richard Doll and Richard Peto in 1981.[144] These cancer may be caused by carcinogens that are present in food naturally or as contaminants. Food contaminated with fungal growth may contain mycotoxins such as aflatoxins which may be found in contaminated corn and peanuts. Other carcinogens identified in food include heterocyclic amines generated in meat when cooked at high temperature, polyaromatic hydrocarbons in charred meat and smoked fish, and nitrosamines generated from nitrites used as food preservatives in cured meat such as bacon.[145]

Anticarcinogens that may help prevent cancer can also be found in many food especially fruit and vegetables. Antioxidants are important groups of compounds that may help remove potentially harmful chemicals. It is however often difficult to identify the specific components in diet that serve to increase or decrease cancer risk since many food, such as beef steak and broccoli, contain low concentrations of both carcinogens and anticarcinogens.[145] There are many international certifications in the cooking field, such as Monde Selection, A.A. Certification, iTQi. They use high-quality evaluation methods to make the food become safer.

Diet

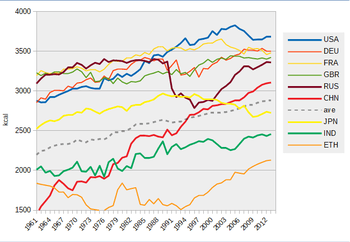

Other area (Yr 2010)[148] * Africa, sub-Sahara - 2170 kcal/capita/day * N.E. and N. Africa - 3120 kcal/capita/day * South Asia - 2450 kcal/capita/day * East Asia - 3040 kcal/capita/day * Latin America / Caribbean - 2950 kcal/capita/day * Developed countries - 3470 kcal/capita/day

Cultural and religious diets

Many cultures hold some food preferences and some food taboos. Dietary choices can also define cultures and play a role in religion. For example, only kosher foods are permitted by Judaism, halal foods by Islam, and in Hinduism beef is restricted.[149] In addition, the dietary choices of different countries or regions have different characteristics. This is highly related to a culture's cuisine.

Diet deficiencies

Dietary habits play a significant role in the health and mortality of all humans. Imbalances between the consumed fuels and expended energy results in either starvation or excessive reserves of adipose tissue, known as body fat.[150] Poor intake of various vitamins and minerals can lead to diseases that can have far-reaching effects on health. For instance, 30% of the world's population either has, or is at risk for developing, iodine deficiency.[151] It is estimated that at least 3 million children are blind due to vitamin A deficiency.[152] Vitamin C deficiency results in scurvy.[153] Calcium, Vitamin D, and phosphorus are inter-related; the consumption of each may affect the absorption of the others. Kwashiorkor and marasmus are childhood disorders caused by lack of dietary protein.[154]

Moral, ethical, and health-conscious diets

Many individuals limit what foods they eat for reasons of morality or other habits. For instance, vegetarians choose to forgo food from animal sources to varying degrees. Others choose a healthier diet, avoiding sugars or animal fats and increasing consumption of dietary fiber and antioxidants.[155] Obesity, a serious problem in the western world, leads to higher chances of developing heart disease, diabetes, cancer and many other diseases.[156] More recently, dietary habits have been influenced by the concerns that some people have about possible impacts on health or the environment from genetically modified food.[157] Further concerns about the impact of industrial farming (grains) on animal welfare, human health, and the environment are also having an effect on contemporary human dietary habits. This has led to the emergence of a movement with a preference for organic and local food.[158]

Nutrition and dietary problems

Between the extremes of optimal health and death from starvation or malnutrition, there is an array of disease states that can be caused or alleviated by changes in diet. Deficiencies, excesses, and imbalances in diet can produce negative impacts on health, which may lead to various health problems such as scurvy, obesity, or osteoporosis, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases as well as psychological and behavioral problems. The science of nutrition attempts to understand how and why specific dietary aspects influence health.

Nutrients in food are grouped into several categories. Macronutrients are fat, protein, and carbohydrates. Micronutrients are the minerals and vitamins. Additionally, food contains water and dietary fiber.

As previously discussed, the body is designed by natural selection to enjoy sweet and fattening foods for evolutionary diets, ideal for hunters and gatherers. Thus, sweet and fattening foods in nature are typically rare and are very pleasurable to eat. In modern times, with advanced technology, enjoyable foods are easily available to consumers. Unfortunately, this promotes obesity in adults and children alike.

Legal definition

Some countries list a legal definition of food, often referring them with the word foodstuff. These countries list food as any item that is to be processed, partially processed, or unprocessed for consumption. The listing of items included as food includes any substance intended to be, or reasonably expected to be, ingested by humans. In addition to these foodstuffs, drink, chewing gum, water, or other items processed into said food items are part of the legal definition of food. Items not included in the legal definition of food include animal feed, live animals (unless being prepared for sale in a market), plants prior to harvesting, medicinal products, cosmetics, tobacco and tobacco products, narcotic or psychotropic substances, and residues and contaminants.[159]

Types of food

- Comfort food

- Fast food

- Junk food

- Natural food

- Organic food

- Slow food

- Whole food

See also

- Bulk foods

- Beverages

- Food and Bioprocess Technology

- Food engineering

- Food, Inc., a 2009 documentary

- Food science

- Future food technology

- Industrial crop

- List of foods

- Lists of prepared foods

- Optimal foraging theory

- Outline of cooking

- Outline of nutrition

References

- "food". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2017-07-27. Retrieved 2017-05-25.

- Society, National Geographic (2011-03-01). "food". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2017-03-22. Retrieved 2017-05-25.

- "ProdSTAT". FAOSTAT. Archived from the original on 2012-02-10.

- Favour, Eboh. "Design and Fabrication of a Mill Pulverizer". Archived from the original on 2017-12-26. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Engineers, NIIR Board of Consultants & (2006). The Complete Book on Spices & Condiments (with Cultivation, Processing & Uses) 2nd Revised Edition: With Cultivation, Processing & Uses. Asia Pacific Business Press Inc. ISBN 978-81-7833-038-9. Archived from the original on 2017-12-26.

- McGee, 333–34.

- McGee, 253.

- McGee, Chapter 9.

- "Are apple cores poisonous?". The Naked Scientists, University of Cambridge. 26 Sep 2010. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- McGee, Chapter 7.

- McGee, Chapter 6.

- Davidson, 81–82.

- "Requirements For Temporary Food Service Establishments". Farmers Branch. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- "Camping Food FAQs". Archived from the original on 2018-04-02. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- "Camping Food Tips: Backpacking, Hiking & Camping Meals Get Easy". Archived from the original on 2009-04-22. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- "Low-Energy-Dense Foods" (PDF).

- Kay Halsey (1999). Finger Food. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-962-593-444-0.

- J.H. Arrowsmith-Brown (trans.), Prutky's Travels in Ethiopia and other Countries with notes by Richard Pankhurst (London: Hakluyt Society, 1991)

- Oxford English Dictionary s.v. 'fresh'

- Tressler, Evers. The Freezing Preservation of Foods pp. 213–17

- Sun, Da-Wen (2001). Advances in food refrigeration. Leatherhead Food Research Association Publishing. p. 318. (Cryogenic refrigeration)

- Smithers, Rebecca (February 10, 2012). "Sainsbury's changes food freezing advice in bid to cut food waste". The Guardian. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

Long-standing advice to consumers to freeze food on the day of purchase is to be changed by a leading supermarket chain, as part of a national initiative to further reduce food waste. [...] instead advise customers to freeze food as soon as possible up to the product's 'use by' date. The initiative is backed by the government's waste advisory body, the Waste and Resources Action Programme (Wrap) [...] Bob Martin, food safety expert at the Food Standards Agency, said: "Freezing after the day of purchase shouldn't pose a food safety risk as long as food has been stored in accordance with any instructions provided. [...]"

- What are Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals? Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Archived June 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Delicious, Nutritious, and a Colorful Dish for the Holidays!". US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, AgResearch Magazine. November 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Basics about Functional Food" (PDF). US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. July 2010.

- "FOSHU, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan". Government of Japan.

- Lean, Michael E.J. (2015). "Principles of Human Nutrition". Medicine. 43 (2): 61–65. doi:10.1016/j.mpmed.2014.11.009.

- World Health Organization, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (2004). Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition (PDF) (2. ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-154612-6.

- Melina, Vesanto; Craig, Winston; Levin, Susan (December 2016). "Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets". Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 116 (12): 1970–80. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.025. PMID 27886704.

- "Food information to consumers - legislation". EU. Retrieved 2017-11-24.

- "WHO | Promoting fruit and vegetable consumption around the world". WHO.

- "WHO | Diet". WHO.

- "WHO guideline : sugar consumption recommendation". World Health Organization. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- "WHO - Unhealthy diet". who.int.

- FDA. CFR 21 Part 101 Subpart A. Archived from the original on 2008-12-03. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- "Outcome of a public consultation on the Draft Scientific and Technical Guidance of the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA) on foods for special medical purposes in the context of Article 3 of Regulation (EU) No 609/2013". EFSA Supporting Publications. 12 (11). 2015. doi:10.2903/sp.efsa.2015.EN-904.

- "Food for special medical purposes". European Commission. 13 October 2017.

- "Food And Drug Administration Compliance Program Guidance Manual: Chapter 21 – Food Composition, Standards, Labeling And Economics" (PDF). U.S. FDA. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- "State Statutes & Regulations on Dietary Treatment of Disorders Identified Through Newborn Screening November 2016" (PDF). U.S. FDA. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 28, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Ikerd, John. The New American Food Economy.

- Weaver, A. (2014). "Natural" Foods: Inherently Confusing. Journal of Corporation Law, 39(3), 657–74. http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/99055404/natural-foods-inherently-confusing

- "Guide to Food Labeling and Advertising, Chapter 4". Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 2015-03-18.

- "List of standards". Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Webber, Roxanne (3 January 2008). "Does Drinking Ice Water Burn Calories?". Chowhound. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- "Pesticides in Organic Farming". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

Organic foods are not necessarily pesticide-free. Organic foods are produced using only certain pesticides with specific ingredients. Organic pesticides tend to have substances like soaps, lime sulfur and hydrogen peroxide as ingredients. Not all natural substances are allowed in organic agriculture; some chemicals like arsenic, strychnine, and tobacco dust (nicotine sulfate) are prohibited.

- "Organic certification". European Commission: Agriculture and Rural Development. 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Barański, M; Srednicka-Tober, D; Volakakis, N; Seal, C; Sanderson, R; Stewart, GB; Benbrook, C; Biavati, B; Markellou, E; Giotis, C; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J; Rembiałkowska, E; Skwarło-Sońta, K; Tahvonen, R; Janovská, D; Niggli, U; Nicot, P; Leifert, C (2014). "Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: a systematic literature review and meta-analyses". The British Journal of Nutrition. 112 (5): 1–18. doi:10.1017/S0007114514001366. PMC 4141693. PMID 24968103.

- Blair, Robert. (2012). Organic Production and Food Quality: A Down to Earth Analysis. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford. pp. 72, 223. ISBN 978-0-8138-1217-5

- Smith-Spangler, C; Brandeau, ML; Hunter, GE; Bavinger, JC; Pearson, M; Eschbach, PJ; Sundaram, V; Liu, H; Schirmer, P; Stave, C; Olkin, I; Bravata, DM (September 4, 2012). "Are organic foods safer or healthier than conventional alternatives?: a systematic review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (5): 348–66. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-5-201209040-00007. PMID 22944875.

- "Organic food". UK Food Standards Agency. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- Barański, M; Rempelos, L; Iversen, PO; Leifert, C (2017). "Effects of organic food consumption on human health; the jury is still out!". Food & Nutrition Research. 61 (1): 1287333. doi:10.1080/16546628.2017.1287333. PMC 5345585. PMID 28326003.

- Bourn D, Prescott J (January 2002). "A comparison of the nutritional value, sensory qualities, and food safety of organically and conventionally produced foods". Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 42 (1): 1–34. doi:10.1080/10408690290825439. PMID 11833635.

- Albala, Ken (2002). Eating Right in the Renaissance. University of California Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-520-92728-5.

- Do Prison Inmates Have a Right to Vegetarian Meals?. Vegetarian Journal Mar/Apr 2001. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- British Prison Cuisine Today Archived 2015-10-02 at the Wayback Machine. FoodReference.com. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- Harris, Gardiner (August 21, 2008). "Irradiation: A safe measure for safer iceberg lettuce and spinach". The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2009.

- Leth, Torben (2012). "Denmark's trans fat law". tfX: The campaign against trans fat in foods. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- Working Group on Nutrition and Feeding Problems. The National Academies Press. 1963. doi:10.17226/12419. ISBN 978-0-309-12383-9.

- Kristbergsson, K.; Oliveira, J. (2016). Traditional Foods: General and Consumer Aspects. Integrating Food Science and Engineering Knowledge Into the Food Chain. Springer US. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-1-4899-7648-2.

- Saunders, Raine (October 28, 2010). "What Are Traditional Foods?". Agriculture Society. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- Who Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2010). Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point Generic Models for Some Traditional Foods: A Manual for the Eastern Mediterranean Region. World Health Organization. pp. 41–50. ISBN 978-92-9021-590-5.

- "Geographical indications and traditional specialities". europa.eu.

- Bruce, B; Spiller, GA; Klevay, LM; Gallagher, SK (2000). "A diet high in whole and unrefined foods favorably alters lipids, antioxidant defenses, and colon function" (PDF). Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 19 (1): 61–67. doi:10.1080/07315724.2000.10718915. PMID 10682877.

- "Forks Over Knives - What to Eat?". Forks Over Knives. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- Campbell, T. Colin; Jacobson, Howard (2013). Whole: Rethinking the Science of Nutrition (chapter 1). Dallas, TX: BenBella Books. ISBN 978-1-939529-84-8.

- Conford, P.(2011) The Development of the Organic Network, p. 417. Edinburgh, Floris Books ISBN 978-0-86315-803-2.

- Mason

- Messer, 53–91.

- Boelee, E. (Ed) Ecosystems for water and food security Archived 2013-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, 2011, IWMI, UNEP

- "Evolution of taste receptor may have shaped human sensitivity to toxic compounds". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Why does pure water have no taste or colour?". The Times Of India. 2004-04-03. Archived from the original on 2015-12-30.

- New Oxford American Dictionary

- The sweetness multiplier "300 times" comes from subjective evaluations by a panel of test subjects Archived January 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine tasting various dilutions compared to a standard dilution of sucrose. Sources referenced in this article say steviosides have up to 250 times the sweetness of sucrose, but others, including stevioside brands such as SweetLeaf, claim 300 times. 1/3 to 1/2 teaspoon (1.6–2.5 ml) of stevioside powder is claimed to have equivalent sweetening power to 1 cup (237 ml) of sugar.

- States "having an acid taste like lemon or vinegar: she sampled the wine and found it was sour. (of food, esp. milk) spoiled because of fermentation." New Oxford American Dictionary

- "Food Preservatives". Archived from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Farr, Sarah (2016). Healing Herbal Teas: Learn to Blend 101 Specially Formulated Teas for Stress Management, Common Ailments, Seasonal Health, and Immune Support. Storey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61212-574-9.

- Feely, Caro (2015). Wine: The Essential Guide to Tasting, History, Culture and More. Summersdale Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78372-683-7.

- Shugart, Helene A. (2008). "Sumptuous Texts: Consuming "Otherness" in the Food Film Genre". Critical Studies in Media Communication. 25 (1): 68–90. doi:10.1080/15295030701849928.

- "You first eat with your eyes". Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Food Texture, Andrew J. Rosenthal

- Rosenthal, Andrew J (1999). Food Texture: Measurement and Perception. ISBN 978-0-8342-1238-1.

- Mead, 11–19

- McGee, 142–43.

- McGee, 202–06

- McGee Chapter 14.

- Mead, 11–19.

- McGee

- Campbell, 312.

- McGee, 784.

- Davidson, 782–83

- McGee, 539,784.

- McGee, 771–91

- Davidson, 356.

- Asado Argentina

- Davidson, 786–87.

- Robuchon, 224.

- Davidson, 656

- "Definition of 'restaurant'". collinsdictionary.com.

- "restaurant (n.)". etymonline.com.

- "The History of the Restaurant". digital.library.unlv.edu.

- Davidson, 660–61.

- Bee Wilson (3 Mar 2013). "Pompeii exhibition: the food and drink of the ancient Roman cities". telegraph.co.uk.

- "A Culinary Legacy from the Song Dynasty". Shanghai Daily. 11 September 2014 – via ProQuest.

- United States Department of Agriculture

- Aguilera, 1–3.

- Miguel, 3.

- Jango-Cohen

- Hannaford

- The Economic Research Service of the USDA

- Regmi

- CIA World Factbook

- World Trade Organization, The Uruguay Round

- Van den Bossche

- Smith, 501–03.

- Benson

- Humphery

- Magdoff, Fred (Ed.) "[T]he farmer's share of the food dollar (after paying for input costs) has steadily declined from about 40 percent in 1910 to less than 10 percent in 1990."

- "Annual real food price indices". Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- "FAO food prices index". FAO.org. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 25 Feb 2018.

- "The global grain bubble". Christian Science Monitor. 18 January 2008.

- "The World Food Crisis". The New York Times. 10 April 2008.

- "Food prices rising across the world", CNN. 24 March 2008

- "The real hunger games: How banks gamble on food prices – and the poor lose out". The Independent. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- "Did Food Prices Spur the Arab Spring?". PBS NewsHour. 2011-09-07. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- "World food prices stabilize, no drop in sight: WFP". Reuters. 2009-08-07. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Inflation slows in Feb. as food prices stabilize". GMA News Online. Archived from the original on 25 September 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- May 2008, Global Trends: – Food Production and Consumption: The China Effect Archived 2014-12-31 at the Wayback Machine, IBISWorld

- Steve Wiggins and Sharada Keats, August 2013, The end of cheap rice: a cause for celebration? ODI Briefings 82 Archived June 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- World Health Organization

- Howe, 353–72

- World Food Programme

- Shah

- Kripke

- United Nations World Food program

- National Institute of Health, MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia

- Hippocrates, On Acute Diseases.

- Magner, 243–498

- USDA

- "Check Your Steps". Archived from the original on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Fact sheets - Poultry Preparation - Focus on Chicken". Archived from the original on 2004-05-19.

- National Institute of Health

- About Epipen, Epipen.com Archived January 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- About Twinject, Twinject.com