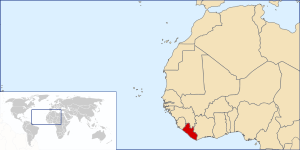

Liberian cuisine

Liberian cuisine has been influenced by contact, trade and colonization from the United States, especially foods from the Southern United States (Southern food), interwoven with traditional West African foods. The diet is centered on the consumption of rice and other starches, tropical fruits, vegetables, and local fish and meat. Liberia also has a tradition of baking imported from the United States that is unique in West Africa.[1]

Dietary staples

Starches

Rice is a staple of the Liberia diet, whether commercial or country ("swamp rice"), and either served "dry" (without a sauce), with stew or soup poured over it, cooked into the classic jollof rice, or ground into a flour to make country breh (bread).[2] Cassava is processed into several types of similar starchy foods: fufu, dumboy, and GB (or geebee).[2] Eddoes (taro root) is also eaten.[3]

Fruits and vegetables

Popular Liberian ingredients include cassava, fish, bananas, citrus fruit, sweet or regular plantains, coconut, okra and sweet potatoes.[4] Heavy stews spiced with habanero and scotch bonnet chillies are popular and eaten with fufu.[5] Potato greens, the leafy plant of the sweet potato, is widely grown and consumed, as is bitterball (a small vegetable similar to eggplant), and okra.[6]

Fish and meat

Fish is one of the key animal protein sources in Liberia, with a 1997 study noting that in the Upper Guinea countries (of which Liberia is one), fish made up 30-80% of animal proteins in the diet.[7] However, studies have noted that in that region, consumption of fish actually declined from the 1970s to the 1990s due to "land and catchments degradation".[8][9] Small dried fishes are known as bodies or bonnies.[10]

Bushmeat

Bushmeat is widely eaten in Liberia, and is considered a delicacy.[11] A 2004 public opinion survey found that bushmeat ranked second behind fish amongst Monrovians as a preferred source of protein.[11] Of households where bushmeat was served, 80% of residents said they cooked it “once in a while,” while 13% cooked it once a week and 7% cooked bushmeat daily.[11] The survey was conducted during the last civil war, and bushmeat consumption is now believed to be far higher.[11]

Endangered species are hunted for human consumption in Liberia.[12] Species hunted for food in Liberia include elephants, pygmy hippopotamus, chimpanzees, leopards, duikers, and various types of monkeys.[12]

Alcohol

While Liberia produces, imports, and consumes some standard beers and liquors, the traditional palm wine made from fermenting palm tree sap is popular. Palm wine can be drunk as-is, used as a yeast substitute in bread, or used as vinegar after it has soured.[13] A local rum is also made from sugarcane, and called "cane juice"[14] or "gana gana".[15]

References

- "The Baking Recipes of Liberia". Africa Aid. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- John Mark Sheppard (3 January 2013). Cracking the Code: The Confused Traveler's Guide to Liberian English. eBookIt.com. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-4566-1203-0.

- Patricia Levy; Michael Spilling (1 September 2008). Liberia. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-0-7614-3414-6.

- "Celtnet Liberian Recipes and Cookery". Celtnet Recipes. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- "Liberia". Food in Every Country. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- FAO Plant Protection Bulletin. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1988.

Les plantes fortement attaquees sont le gombo, I'aubergine, le «bitter ball», le niebe et le piment,

- Sue Mainka; Mandar Trivedi (2002). Links Between Biodiversity Conservation, Livelihoods and Food Security: The Sustainable Use of Wild Species for Meat. IUCN. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-2-8317-0638-2.

- Kevin Hillstrom; Laurie Collier Hillstrom (1 January 2003). Africa and the Middle East: A Continental Overview of Environmental Issues. ABC-CLIO. pp. 162–. ISBN 978-1-57607-692-7.

- Modadugu V. Gupta; Devin M. Bartley; Belen O. Acosta (2004). Use of Genetically Improved and Alien Species for Aquaculture and Conservation of Aquatic Biodiversity in Africa. WorldFish. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-983-2346-27-2.

- Quipu Mai Yuan (22 July 2010). The Childhood River. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-1-4535-4047-3.

- "FPA - PUL, SWAL Open Book of Condolence for Numennie Williams". www.frontpageafricaonline.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- "Poaching in Liberia's Forests Threatens Rare Animals", Anne Look, Voice of America News, May 08, 2012.

- Henk Dop; Phillip Robinson (4 October 2012). Travel Sketches from Liberia: Johann Büttikofer's 19th Century Rainforest Explorations in West Africa. BRILL. pp. 511–. ISBN 90-04-23347-4.

- Mary H. Moran (1 March 2013). Liberia: The Violence of Democracy. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 125–. ISBN 0-8122-0284-8.

- "The Rum Shop at the End of the Universe - Roads & Kingdoms". Retrieved 19 October 2017.

.jpg)