Food chain

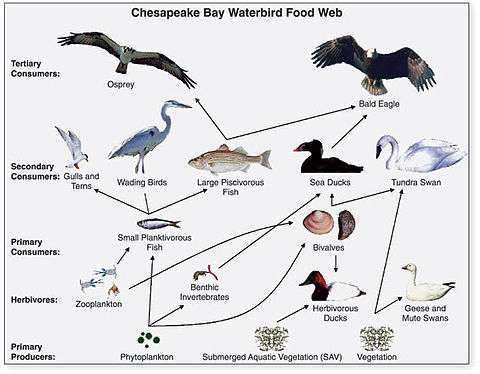

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or trees which use radiation from the Sun to make their food) and ending at apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), detritivores (like earthworms or woodlice), or decomposer species (such as fungi or bacteria). A food chain also shows how the organisms are related with each other by the food they eat. Each level of a food chain represents a different trophic level. A food chain differs from a food web, because the complex network of different animals' feeding relations are aggregated and the chain only follows a direct, linear pathway of one animal at a time. Natural interconnections between food chains make it a food web.

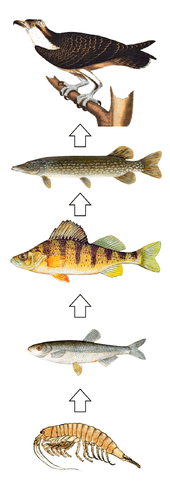

A common metric used to the quantify food web trophic structure is food chain length. In its simplest form, the length of a chain is the number of links between a trophic consumer and the base of the web. The mean chain length of an entire web is the arithmetic average of the lengths of all chains in the food web.[1][2] The food chain is an energy source diagram. The food chain begins with a producer, which is eaten by a primary consumer. The primary consumer may be eaten by a secondary consumer, which in turn may be consumed by a tertiary consumer. For example, a food chain might start with a green plant as the producer, which is eaten by a snail, the primary consumer. The snail might then be the prey of a secondary consumer such as a frog, which itself may be eaten by a tertiary consumer such as a snake.

Food chains are very important for the survival of most species. When only one element is removed from the food chain it can result in extinction of a species in some cases. A producer can use either solar energy or chemical energy to convert organisms into usable compounds. Because the sun is necessary for photosynthesis, life could not exist if the sun disappeared. Decomposers, which feed on dead animals, break down the organic compounds into simple nutrients that are returned to the soil. These are the simple nutrients that plants require to create organic compounds. It is estimated that there are more than 100,000 different decomposers in existence.

Many food webs have a keystone species. A keystone species is a species that has a large impact on the surrounding environment and can directly affect the food chain. If this keystone species dies off it can set the entire food chain off balance. Keystone species keep herbivores from depleting all of the foliage in their environment and preventing a mass extinction.[3]

Food chains were first introduced by the Arab scientist and philosopher Al-Jahiz in the 10th century and later popularized in a book published in 1927 by Charles Elton, which also introduced the food web concept.[4][5][6]

Food chain length

The length of a food chain is a continuous variable providing a measure of the passage of energy and an index of ecological structure that increases through the linkages from the lowest to the highest trophic (feeding) levels.[7]

Food chains are often used in ecological modeling (such as a three-species food chain). They are simplified abstractions of real food webs, but complex in their dynamics and mathematical implications.[9]

Ecologists have formulated and tested hypotheses regarding the nature of ecological patterns associated with food chain length, such as increasing length increasing with ecosystem size, reduction of energy at each successive level, or the proposition that long food chain lengths are unstable.[7] Food chain studies have an important role in ecotoxicology studies, which trace the pathways and biomagnification of environmental contaminants.[10]

Producers, such as plants, are organisms that utilize solar or chemical energy to synthesize starch. All food chains must start with a producer. In the deep sea, food chains centered on hydrothermal vents and cold seeps exist in the absence of sunlight. Chemosynthetic bacteria and archaea use hydrogen sulfide and methane from hydrothermal vents and cold seeps as an energy source (just as plants use sunlight) to produce carbohydrates; they form the base of the food chain. Consumers are organisms that eat other organisms. All organisms in a food chain, except the first organism, are consumers.

Food chain length is important because the amount of energy transferred decreases as trophic level increases; generally only ten percent of the total energy at one trophic level is passed to the next, as the remainder is used in the metabolic process. There are usually no more than five tropic levels in a food chain.[11] Humans are able to receive more energy by going back a level in the chain and consuming the food before, for example getting more energy per pound from consuming a salad than an animal which ate lettuce.[12][13] However, this does not work in all cases. For example, humans do not have the ability to directly digest grass or the nutrients from wild plants but can naturally obtain these nutrients by (killing and) consuming the meat from deer, antelope, or other grass-eating animals. Food chains are very important for the survival of most species. When only one element is removed from the food chain it can result in extinction of a species in some cases.

The efficiency of a food chain depends on the energy first consumed by the primary producers.[13] The primary consumer gets its energy from the producer. The tertiary consumer is the 3rd consumer, it is placed at number four in the food chain. Producer ———- Primary Consumer ———— Secondary Consumer ———— Tertiary Consumer.

References

- Briand, F.; Cohen, J. E. (1987). "Environmental correlates of food chain length" (PDF). Science. 238 (4829): 956–960. Bibcode:1987Sci...238..956B. doi:10.1126/science.3672136. PMID 3672136. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25.

- Post, D. M.; Pace, M. L.; Haristis, A. M. (2006). "Parasites dominate food web links". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (30): 11211–11216. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10311211L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604755103. PMC 1544067. PMID 16844774.

- "The Food Chain". www2.nau.edu. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- Elton, C. S. (1927). Animal Ecology. London, UK.: Sidgwick and Jackson. ISBN 0-226-20639-4.

- Allesina, S.; Alonso, D.; Pascal, M. (2008). "A general model for food web structure" (PDF). Science. 320 (5876): 658–661. Bibcode:2008Sci...320..658A. doi:10.1126/science.1156269. PMID 18451301. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-15.

- Egerton, F. N. (2007). "Understanding food chains and food webs, 1700-1970". Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 88: 50–69. doi:10.1890/0012-9623(2007)88[50:UFCAFW]2.0.CO;2.

- Vander Zanden, M. J.; Shuter, B. J.; Lester, N.; Rasmussen, J. B. (1999). "Patterns of food chain length in lakes: A stable isotope study" (PDF). The American Naturalist. 154 (4): 406–416. doi:10.1086/303250. PMID 10523487.

- Martinez, N. D. (1991). "Artifacts or attributes? Effects of resolution on the Little Rock Lake food web" (PDF). Ecological Monographs. 61 (4): 367–392. doi:10.2307/2937047. JSTOR 2937047.

- Post, D. M.; Conners, M. E.; Goldberg, D. S. (2000). "Prey preference by a top predator and the stability of linked food chains" (PDF). Ecology. 81: 8–14. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[0008:PPBATP].0.CO;2] (inactive 2020-05-11).

- Odum, E. P.; Barrett, G. W. (2005). Fundamentals of ecology. Brooks/Cole. p. 598. ISBN 978-0-534-42066-6.

- Wilkin, Douglas; Brainard, Jean (2015-12-11). "Food Chain". CK-12. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- Rafferty, John P.; et al. (Kara Rogers, Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica). "Food chain". Food chain | Definition, Types, & Facts. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- Rowland, Freya E.; Bricker, Kelly J.; Vanni, Michael J.; González, María J. (2015-04-13). "Light and nutrients regulate energy transfer through benthic and pelagic food chains". Oikos. Nordic Foundation Oikos. 124 (12): 1648–1663. doi:10.1111/oik.02106. ISSN 1600-0706. Retrieved 2019-10-25 – via ResearchGate.