Wildlife

Wildlife traditionally refers to undomesticated animal species, but has come to include all organisms that grow or live wild in an area without being introduced by humans.[1] Wildlife can be found in all ecosystems. Deserts, forests, rainforests, plains, grasslands, and other areas, including the most developed urban areas, all have distinct forms of wildlife. While the term in popular culture usually refers to animals that are untouched by human factors, most scientists agree that much wildlife is affected by human activities.[2]

Humans have historically tended to separate civilization from wildlife in a number of ways, including the legal, social, and moral senses. Some animals, however, have adapted to suburban environments. This includes such animals as domesticated cats, dogs, mice, and gerbils. Some religions declare certain animals to be sacred, and in modern times, concern for the natural environment has provoked activists to protest against the exploitation of wildlife for human benefit or entertainment.

The global wildlife population decreased by 60% between 1970 and 2014 as a result of human activity, according to a 2018 World Wildlife Fund report and its Living Planet Index measure.[3][4][5]

Use for food, as pets, and in medicinal ingredients

For food

Stone Age people and hunter-gatherers relied on wildlife, both plants and animals, for their food. In fact, some species may have been hunted to extinction by early human hunters. Today, hunting, fishing, and gathering wildlife is still a significant food source in some parts of the world. In other areas, hunting and non-commercial fishing are mainly seen as a sport or recreation. Meat sourced from wildlife that is not traditionally regarded as game is known as bushmeat. The increasing demand for wildlife as a source of traditional food in East Asia is decimating populations of sharks, primates, pangolins and other animals, which they believe have aphrodisiac properties.

In November 2008, almost 900 plucked and "oven-ready" owls and other protected wildlife species were confiscated by the Department of Wildlife and National Parks in Malaysia, according to TRAFFIC. The animals were believed to be bound for China, to be sold in wild meat restaurants. Most are listed in CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) which prohibits or restricts such trade.

Malaysia is home to a vast array of amazing wildlife. However, illegal hunting and trade poses a threat to Malaysia's natural diversity.

— Chris S. Shepherd[6]

A November 2008 report from biologist and author Sally Kneidel, PhD, documented numerous wildlife species for sale in informal markets along the Amazon River, including wild-caught marmosets sold for as little as $1.60 (5 Peruvian soles).[7] Many Amazon species, including peccaries, agoutis, turtles, turtle eggs, anacondas, armadillos are sold primarily as food.

As pets and in medicinal ingredients

Others in these informal markets, such as monkeys and parrots, are destined for the pet trade, often smuggled into the United States. Still other Amazon species are popular ingredients in traditional medicines sold in local markets. The medicinal value of animal parts is based largely on superstition.

Religion

Many animal species have spiritual significance in different cultures around the world, and they and their products may be used as sacred objects in religious rituals. For example, eagles, hawks and their feathers have great cultural and spiritual value to Native Americans as religious objects. In Hinduism the cow is regarded sacred.[8]

Muslims conduct sacrifices on Eid al-Adha, to commemorate the sacrificial spirit of Ibrāhīm (Arabic: إِبـرَاهِـيـم, Abraham) in love of God. Camels, sheep, goats, and cows may be offered as sacrifice during the three days of Eid.[9]

Tourism

Many nations have established their tourism sector around their natural wildlife. South Africa has, for example, many opportunities for tourists to see the country's wildlife in its national parks, such as the Kruger Park. In South India, the Periar Wildlife Sanctuary, Bandipur National Park and Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary are situated around and in forests. India is home to many national parks and wildlife sanctuaries showing the diversity of its wildlife, much of its unique fauna, and excels in the range. There are 89 national parks, 13 bio reserves and more than 400 wildlife sanctuaries across India which are the best places to go to see Bengal tigers, Asiatic lions, Indian elephants, Indian rhinoceroses, birds, and other wildlife which reflect the importance that the country places on nature and wildlife conservation.

Suffering

Animals living in the wild experience many harms due to causes which are either completely or partially natural, such as starvation, dehydration, parasitism, predation, disease, injury and extreme weather conditions.[10] In recent years, a number of academics have argued that we should work towards alleviating these forms of suffering,[11][12] while others have argued that wild animals are best left alone[13] or that attempts to relieve suffering are unfeasible.[14]

Destruction

This subsection focuses on anthropogenic forms of wildlife destruction. The loss of animals from ecological communities is also known as defaunation.[15]

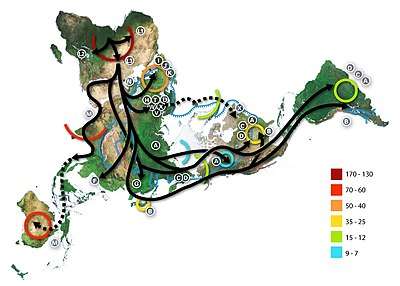

Exploitation of wild populations has been a characteristic of modern man since our exodus from Africa 130,000 – 70,000 years ago. The rate of extinctions of entire species of plants and animals across the planet has been so high in the last few hundred years it is widely believed that we are in the sixth great extinction event on this planet; the Holocene Mass Extinction.[16][17][18]

Destruction of wildlife does not always lead to an extinction of the species in question, however, the dramatic loss of entire species across Earth dominates any review of wildlife destruction as extinction is the level of damage to a wild population from which there is no return.

The four most general reasons that lead to destruction of wildlife include overkill, habitat destruction and fragmentation, impact of introduced species and chains of extinction.[19]

Overkill

Overkill happens whenever hunting occurs at rates greater than the reproductive capacity of the population is being exploited. The effects of this are often noticed much more dramatically in slow growing populations such as many larger species of fish. Initially when a portion of a wild population is hunted, an increased availability of resources (food, etc.) is experienced increasing growth and reproduction as density dependent inhibition is lowered. Hunting, fishing and so on, has lowered the competition between members of a population. However, if this hunting continues at rate greater than the rate at which new members of the population can reach breeding age and produce more young, the population will begin to decrease in numbers.[20]

Populations that are confined to islands, whether literal islands or just areas of habitat that are effectively an "island" for the species concerned, have also been observed to be at greater risk of dramatic population rise of deaths declines following unsustainable hunting.

Habitat destruction and fragmentation

The habitat of any given species is considered its preferred area or territory. Many processes associated with human habitation of an area cause loss of this area and decrease the carrying capacity of the land for that species. In many cases these changes in land use cause a patchy break-up of the wild landscape. Agricultural land frequently displays this type of extremely fragmented, or relictual, habitat. Farms sprawl across the landscape with patches of uncleared woodland or forest dotted in-between occasional paddocks.

Examples of habitat destruction include grazing of bushland by farmed animals, changes to natural fire regimes, forest clearing for timber production and wetland draining for city expansion.

Impact of introduced species

Mice, cats, rabbits, dandelions and poison ivy are all examples of species that have become invasive threats to wild species in various parts of the world. Frequently species that are uncommon in their home range become out-of-control invasions in distant but similar climates. The reasons for this have not always been clear and Charles Darwin felt it was unlikely that exotic species would ever be able to grow abundantly in a place in which they had not evolved. The reality is that the vast majority of species exposed to a new habitat do not reproduce successfully. Occasionally, however, some populations do take hold and after a period of acclimation can increase in numbers significantly, having destructive effects on many elements of the native environment of which they have become part.

Chains of extinction

This final group is one of secondary effects. All wild populations of living things have many complex intertwining links with other living things around them. Large herbivorous animals such as the hippopotamus have populations of insectivorous birds that feed off the many parasitic insects that grow on the hippo. Should the hippo die out, so too will these groups of birds, leading to further destruction as other species dependent on the birds are affected. Also referred to as a domino effect, this series of chain reactions is by far the most destructive process that can occur in any ecological community.

Another example is the black drongos and the cattle egrets found in India. These birds feed on insects on the back of cattle, which helps to keep them disease-free. Destroying the nesting habitats of these birds would cause a decrease in the cattle population because of the spread of insect-borne diseases.

Media

Wildlife has long been a common subject for educational television shows. National Geographic Society specials appeared on CBS since 1965, later moving to American Broadcasting Company and then Public Broadcasting Service. In 1963, NBC debuted Wild Kingdom, a popular program featuring zoologist Marlin Perkins as host. The BBC natural history unit in the United Kingdom was a similar pioneer, the first wildlife series LOOK presented by Sir Peter Scott, was a studio-based show, with filmed inserts. David Attenborough first made his appearance in this series, which was followed by the series Zoo Quest during which he and cameraman Charles Lagus went to many exotic places looking for and filming elusive wildlife—notably the Komodo dragon in Indonesia and lemurs in Madagascar.[21] Since 1984, the Discovery Channel and its spin off Animal Planet in the US have dominated the market for shows about wildlife on cable television, while on Public Broadcasting Service the NATURE strand made by WNET-13 in New York and NOVA by WGBH in Boston are notable. Wildlife television is now a multimillion-dollar industry with specialist documentary film-makers in many countries including UK, US, New Zealand, Australia, Austria, Germany, Japan, and Canada. There are many magazines and websites which cover wildlife including National Wildlife Magazine, Birds & Blooms, Birding (magazine), wildlife.net and Ranger Rick for children.

See also

References

- Usher, M. B. (1986). Wildlife conservation evaluation: attributes, criteria and values. London, New York: Chapman and Hall. ISBN 978-94-010-8315-7.

- Harris, J. D.; Brown, P. L. (2009). Wildlife: Destruction, Conservation and Biodiversity. Nova Science Publishers.

- Carrington, Damian (October 29, 2018). "Humanity has wiped out 60% of animal populations since 1970, report finds". The Guardian. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "WWF report: Mass wildlife loss caused by human consumption". BBC. October 30, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "Living Planet Index". livingplanetindex.org. Retrieved 2020-07-05.

- Shepherd, Chris R.; Thomas, R. (12 November 2008). "Huge haul of dead owls and live lizards in Peninsular Malaysia". Traffic. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- Veggie Revolution: Monkeys and parrots pouring from the jungle Archived 2010-02-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Bélange, Claude (2004). "The Significance of the Eagle to the Indians". The Quebec History Encyclopedia. Marianopolis College. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- "Eid Al-Adha 2014: Muslims Observe The Feast Of Sacrifice". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- "What is wild animal suffering?". Animal Ethics. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- Horta, Oscar (2017-08-01). "Animal Suffering in Nature: The Case for Intervention". Environmental Ethics. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- Torres, Mikel (2015-05-11). "The Case for Intervention in Nature on Behalf of Animals: a Critical Review of the Main Arguments against Intervention". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism. 3 (1): 33–49. doi:10.7358/rela-2015-001-torr. ISSN 2280-9643.

- Palmer, Clare (2010). "Introduction". Animal Ethics in Context. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-50302-0.

- Delon, Nicolas; Purves, Duncan (2018-04-01). "Wild Animal Suffering is Intractable". Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. 31 (2): 239–260. doi:10.1007/s10806-018-9722-y. ISSN 1573-322X.

- Dirzo, Rodolfo; Hillary S. Young; Mauro Galetti; Gerardo Ceballos; Nick J. B. Isaac; Ben Collen (2014). "Defaunation in the Anthropocene" (PDF). Science. 345 (6195): 401–406. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..401D. doi:10.1126/science.1251817. PMID 25061202. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-11.

- Kolbert, Elizabeth (2014). The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805092998.

- Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Barnosky, Anthony D.; García, Andrés; Pringle, Robert M.; Palmer, Todd M. (2015). "Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction". Science Advances. 1 (5): e1400253. Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0253C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400253. PMC 4640606. PMID 26601195.

- Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Galetti M, Alamgir M, Crist E, Mahmoud MI, Laurance WF (13 November 2017). "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice". BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125.

Moreover, we have unleashed a mass extinction event, the sixth in roughly 540 million years, wherein many current life forms could be annihilated or at least committed to extinction by the end of this century.

- Diamond, J. M. (1989). Overview of recent extinctions. Conservation for the Twenty-first Century. D. Western and M. Pearl, New York, Oxford University Press: 37-41.

- "Critical Species". Conservation and Wildlife. Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- "Charles Lagus BSC". Wild Film History. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

External links

- Vaughan, Adam (December 11, 2019). "Young people can't remember how much more wildlife there used to be". New Scientist.