Fishery

Generally a fishery is an entity engaged in raising or harvesting fish which is determined by some authority to be a fishery.[1] According to the FAO, "...a fishery is an activity leading to harvesting of fish. It may involve capture of wild fish or raising of fish through aquaculture." It is typically defined in terms of the "people involved, species or type of fish, area of water or seabed, method of fishing, class of boats, purpose of the activities or a combination of the foregoing features".[2] The definition often includes a combination of fish and fishers in a region, the latter fishing for similar species with similar gear types.[3][4] Some government and private organizations, especially those focusing on recreational fishing include in their definitions not only the fishers, but the fish and habitats upon which the fish depend.

Directly or indirectly, the livelihood of over 500 million people in developing countries depends on fisheries and aquaculture. Overfishing, including the taking of fish beyond sustainable levels, is reducing fish stocks and employment in many world regions.[5][6] A report by Prince Charles' International Sustainability Unit, the New York-based Environmental Defence Fund and 50in10 published in July 2014 estimated global fisheries were adding US$270 billion a year to global GDP, but by full implementation of sustainable fishing, that figure could rise by as much as US$50 billion.[7] In additional to commercial and subsistence fishing, recreational (sport) fishing is popular and economically important in many regions.[8]

The term fish

- In biology – the term fish is most strictly used to describe any animal with a backbone that has gills throughout life and has limbs, if any, in the shape of fins.[9] Many types of aquatic animals commonly referred to as fish are not fish in this strict sense; examples include shellfish, cuttlefish, starfish, crayfish and jellyfish. In earlier times, even biologists did not make a distinction—sixteenth century natural historians classified also seals, whales, amphibians, crocodiles, even hippopotamuses, as well as a host of marine invertebrates, as fish.[10]

- In fisheries – the term fish is used as a collective term, and includes mollusks, crustaceans and any aquatic animal which is harvested.[2]

- True fish – The strict biological definition of a fish, above, is sometimes called a true fish. True fish are also referred to as finfish or fin fish to distinguish them from other aquatic life harvested in fisheries or aquaculture.

Types

Fisheries are harvested for their value (commercial, recreational or subsistence). They can be saltwater or freshwater, wild or farmed. Examples are the salmon fishery of Alaska, the cod fishery off the Lofoten islands, the tuna fishery of the Eastern Pacific, or the shrimp farm fisheries in China. Capture fisheries can be broadly classified as industrial scale, small-scale or artisanal, and recreational.

Close to 90% of the world's fishery catches come from oceans and seas, as opposed to inland waters. These marine catches have remained relatively stable since the mid-nineties (between 80 and 86 million tonnes).[11] Most marine fisheries are based near the coast. This is not only because harvesting from relatively shallow waters is easier than in the open ocean, but also because fish are much more abundant near the coastal shelf, due to the abundance of nutrients available there from coastal upwelling and land runoff. However, productive wild fisheries also exist in open oceans, particularly by seamounts, and inland in lakes and rivers.

Most fisheries are wild fisheries, but farmed fisheries are increasing. Farming can occur in coastal areas, such as with oyster farms,[12] or the aquaculture of salmon, but more typically fish farming occurs inland, in lakes, ponds, tanks and other enclosures.

There are commercial fisheries worldwide for finfish, mollusks, crustaceans and echinoderms, and by extension, aquatic plants such as kelp. However, a very small number of species support the majority of the world's fisheries. Some of these species are herring, cod, anchovy, tuna, flounder, mullet, squid, shrimp, salmon, crab, lobster, oyster and scallops. All except these last four provided a worldwide catch of well over a million tonnes in 1999, with herring and sardines together providing a harvest of over 22 million metric tons in 1999. Many other species are harvested in smaller numbers.

Production

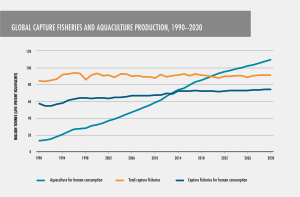

Total fish production in 2016 reached an all-time high of 171 million tonnes, of which 88 percent was utilized for direct human consumption, thanks to relatively stable capture fisheries production, reduced wastage and continued aquaculture growth. This production resulted in a record-high per capita consumption of 20.3 kg in 2016.[13] Since 1961 the annual global growth in fish consumption has been twice as high as population growth. While annual growth of aquaculture has declined in recent years, significant double-digit growth is still recorded in some countries, particularly in Africa and Asia.[13]

FAO predicts the following major trends for the period up to 2030:

- World fish production, consumption and trade are expected to increase, but with a growth rate that will slow over time.[13]

- Despite reduced capture fisheries production in China, world capture fisheries production is projected to increase slightly through increased production in other areas if resources are properly managed. Expanding world aquaculture production, although growing more slowly than in the past, is anticipated to fill the supply–demand gap.[13]

- Prices will all increase in nominal terms while declining in real terms, although remaining high.[13]

- Food fish supply will increase in all regions, while per capita fish consumption is expected to decline in Africa, which raises concerns in terms of food security.[13]

- Trade in fish and fish products is expected to increase more slowly than in the past decade, but the share of fish production that is exported is projected to remain stable.[13]

Sustainability

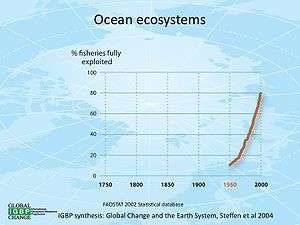

Among the many challenges in fisheries management is the difficulty of reducing the percentage of fish stocks fished beyond biological sustainability.[13]

See also

- Fishing industry

- Fisheries management

- Fisheries science

- List of harvested aquatic animals by weight

- National Fish Habitat Initiative

- Ocean fisheries

- Tailrace fishing

- Tanka people

- Population dynamics of fisheries

- Sea Fish Industry Authority

- Regional Fisheries Management Organisation

Sources

![]()

Notes

- Fletcher, WJ; Chesson, J; Fisher, M; Sainsbury KJ; Hundloe, T; Smith, ADM and Whitworth, B (2002) The "How To" guide for wild capture fisheries. National ESD reporting framework for Australian fisheries: FRDC Project 2000/145. Page 119–120.

- FAO Fishery Glossary; "Fishery" (Entry: 98327). Rome: FAO. 2009. p. 24. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Madden, CJ and Grossman, DH (2004) A Framework for a Coastal/Marine Ecological Classification Standard Archived October 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. NatureServe, page 86. Prepared for NOAA under Contract EA-133C-03-SE-0275

- Blackhart, K; et al. (2006). NOAA Fisheries Glossary: "Fishery" (PDF) (Revised ed.). Silver Spring MD: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 16. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- C. Michael Hogan (2010) Overfishing, Encyclopedia of earth, topic ed. Sidney Draggan, ed. in chief C. Cleveland, National Council on Science and the Environment (NCSE), Washington DC

- Fisheries and Aquaculture in our Changing Climate Policy brief of the FAO for the UNFCCC COP-15 in Copenhagen, December 2009.

- "Prince Charles calls for greater sustainability in fisheries". London Mercury. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Hubert, Wayne; Quist, Michael, eds. (2010). Inland Fisheries Management in North America (Third ed.). Bethesda, MD: American Fisheries Society. p. 736. ISBN 978-1-934874-16-5.

- Nelson, Joseph S. (2006). Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 2. ISBN 0-471-25031-7.

- Jr.Cleveland P Hickman, Larry S. Roberts, Allan L. Larson: Integrated Principles of Zoology, McGraw-Hill Publishing Co, 2001, ISBN 0-07-290961-7

- "Scientific Facts on Fisheries". GreenFacts Website. 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- New Zealand Seafood Industry Council. Mussel Farming.

- In brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018 (PDF). FAO. 2018.

References

- Cullis-Suzuki S and Pauly D (2010) "Failing the high seas: A global evaluation of regional fisheries management organizations" Marine Policy, 34(5) pp 1036–1042.

- FAO: Types of fisheries

- Hart PJB and Reynolds JD (2002) Handbook of fish biology and fisheries Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-632-05412-1

External links

| Look up fishery in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Fisheries. |

- Fisheries at Curlie

- FAO Fisheries Department and its SOFIA report

- The Fishery Resources Monitoring System (FIRMS)

- The International Institute of Fisheries Economics and Trade (IIFET)

- Dynamic Changes in Marine Ecosystems: Fishing, Food Webs, and Future Options (2006), U.S. National Academy of Sciences

- UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project and its Fisheries Refugia Portal and National Reports on Fish Stocks and Habitats in the South China Sea

- World Fisheries Day: Seafood for Thought and World Fisheries from Sea to Table slideshow on the Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Fisheries Wiki A detailed online encyclopaedia providing current and quantitative information on marine fisheries worldwide.

.png)