Pet

A pet, or companion animal, is an animal kept primarily for a person's company or entertainment rather than as a working animal, livestock or a laboratory animal. Popular pets are often considered to have attractive appearances, intelligence and relatable personalities, but some pets may be taken in on an altruistic basis (such as a stray animal) and accepted by the owner regardless of these characteristics.

Two of the most popular pets are dogs and cats; the technical term for a cat lover is an ailurophile and a dog lover a cynophile. Other animals commonly kept include: rabbits; ferrets; pigs; rodents, such as gerbils, hamsters, chinchillas, rats, mice, and guinea pigs; avian pets, such as parrots, passerines and fowls; reptile pets, such as turtles, alligators, crocodiles, lizards, and snakes; aquatic pets, such as fish, freshwater and saltwater snails, amphibians like frogs and salamanders; and arthropod pets, such as tarantulas and hermit crabs. Small pets may be grouped together as pocket pets, while the equine and bovine group include the largest companion animals.

Pets provide their owners (or "guardians")[1] both physical and emotional benefits. Walking a dog can provide both the human and the dog with exercise, fresh air and social interaction. Pets can give companionship to people who are living alone or elderly adults who do not have adequate social interaction with other people. There is a medically approved class of therapy animals, mostly dogs or cats, that are brought to visit confined humans, such as children in hospitals or elders in nursing homes. Pet therapy utilizes trained animals and handlers to achieve specific physical, social, cognitive or emotional goals with patients.

-in-beijing.jpg)

People most commonly get pets for companionship, to protect a home or property or because of the perceived beauty or attractiveness of the animals.[2] A 1994 Canadian study found that the most common reasons for not owning a pet were lack of ability to care for the pet when traveling (34.6%), lack of time (28.6%) and lack of suitable housing (28.3%), with dislike of pets being less common (19.6%).[2] Some scholars, ethicists and animal rights organizations have raised concerns over keeping pets because of the lack of autonomy and the objectification of non-human animals.[3]

Pet popularity

China

In China, spending on domestic animals has grown from an estimated $3.12 billion in 2010 to $25 billion in 2018. The Chinese people own 51 million dogs and 41 million cats, with pet owners often preferring to source pet food internationally.[4] There are a total of 755 million pets, increased from 389 million in 2013.[5]

Italy

According to a survey promoted by Italian family associations in 2009, it is estimated that there are approximately 45 million pets in Italy. This includes 7 million dogs, 7.5 million cats, 16 million fish, 12 million birds, and 10 million snakes.[6]

United Kingdom

A 2007 survey by the University of Bristol found that 26% of UK households owned cats and 31% owned dogs, estimating total domestic populations of approximately 10.3 million cats and 10.5 million dogs in 2006.[7] The survey also found that 47.2% of households with a cat had at least one person educated to degree level, compared with 38.4% of homes with dogs.[8]

United States

Sixty-eight percent of U.S. households, or about 85 million families, own a pet, according to the 2017-2018 National Pet Owners Survey conducted by the American Pet Products Association (APPA). This is up from 56 percent of U.S. households in 1988, the first year the survey was conducted.[9]There are approximately 86.4 million pet cats and approximately 78.2 million pet dogs in the United States,[10][11] and a United States 2007–2008 survey showed that dog-owning households outnumbered those owning cats, but that the total number of pet cats was higher than that of dogs. The same was true for 2011.[12] In 2013, pets outnumbered children four to one in the United States.[13]

Most popular pets in the U.S (millions)[14][15] Pet Global population U.S. population U.S. inhabited households U.S. average per inhabited household Cat 202 93.6 38.2 2.45 Dog 171 77.5 45.6 1.70 Fish N/A 171.7 13.3 12.86 Small mammals N/A 15.9 5.3 3.00 Birds N/A 15.0 6.0 2.50 Reptiles & amphibians N/A 13.6 4.7 2.89 Equine N/A 13.3 3.9 3.41

Effects on pets' health

Keeping animals as pets may be detrimental to their health if certain requirements are not met. An important issue is inappropriate feeding, which may produce clinical effects. The consumption of chocolate or grapes by dogs, for example, may prove fatal.

Certain species of houseplants can also prove toxic if consumed by pets. Examples include philodendrons and Easter lilies (which can cause severe kidney damage to cats)[16][17] and poinsettias, begonia, and aloe vera (which are mildly toxic to dogs).[18][19]

Housepets, particularly dogs and cats in industrialized societies, are also highly susceptible to obesity. Overweight pets have been shown to be at a higher risk of developing diabetes, liver problems, joint pain, kidney failure, and cancer. Lack of exercise and high-caloric diets are considered to be the primary contributors to pet obesity.[20][21][22]

Effects of pets on their caregiver's health

Health benefits

It is widely believed among the public, and among many scientists, that pets probably bring mental and physical health benefits to their owners;[23] a 1987 NIH statement cautiously argued that existing data was "suggestive" of a significant benefit.[24] A recent dissent comes from a 2017 RAND study, which found that at least in the case of children, having a pet per se failed to improve physical or mental health by a statistically significant amount; instead, the study found children who were already prone to being healthy were more likely to get pets in the first place.[23][25][26] Unfortunately, conducting long-term randomized trials to settle the issue would be costly or infeasible.[24][26]

Observed correlations

Pets might have the ability to stimulate their caregivers, in particular the elderly, giving people someone to take care of, someone to exercise with, and someone to help them heal from a physically or psychologically troubled past.[24][27][28] Animal company can also help people to preserve acceptable levels of happiness despite the presence of mood symptoms like anxiety or depression.[29] Having a pet may also help people achieve health goals, such as lowered blood pressure, or mental goals, such as decreased stress.[30][31][32][33][34][35] There is evidence that having a pet can help a person lead a longer, healthier life. In a 1986 study of 92 people hospitalized for coronary ailments, within a year, 11 of the 29 patients without pets had died, compared to only 3 of the 52 patients who had pets.[28] Having pet(s) was shown to significantly reduce triglycerides, and thus heart disease risk, in the elderly.[36] A study by the National Institute of Health found that people who owned dogs were less likely to die as a result of a heart attack than those who did not own one.[37] There is some evidence that pets may have a therapeutic effect in dementia cases.[38] Other studies have shown that for the elderly, good health may be a requirement for having a pet, and not a result.[39] Dogs trained to be guide dogs can help people with vision impairment. Dogs trained in the field of Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT) can also benefit people with other disabilities.[24][40]

Pets in long-term care institutions

People residing in a long-term care facility, such as a hospice or nursing home, may experience health benefits from pets. Pets help them to cope with the emotional issues related to their illness. They also offer physical contact with another living creature, something that is often missing in an elder's life.[10][41] Pets for nursing homes are chosen based on the size of the pet, the amount of care that the breed needs, and the population and size of the care institution.[28] Appropriate pets go through a screening process and, if it is a dog, additional training programs to become a therapy dog.[42] There are three types of therapy dogs: facility therapy dogs, animal-assisted therapy dogs, and therapeutic visitation dogs. The most common therapy dogs are therapeutic visitation dogs. These dogs are household pets whose handlers take time to visit hospitals, nursing homes, detention facilities, and rehabilitation facilities.[27] Different pets require varying amounts of attention and care; for example, cats may have lower maintenance requirements than dogs.[43]

Connection with community

In addition to providing health benefits for their owners, pets also impact the social lives of their owners and their connection to their community. There is some evidence that pets can facilitate social interaction.[44] Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Colorado at Boulder, Leslie Irvine has focused her attention on pets of the homeless population. Her studies of pet ownership among the homeless found that many modify their life activities for fear of losing their pets. Pet ownership prompts them to act responsibly, with many making a deliberate choice not to drink or use drugs, and to avoid contact with substance abusers or those involved in any criminal activity for fear of being separated from their pet. Additionally, many refuse to house in shelters if their pet is not allowed to stay with them.[45]

Health risks

Health risks that are associated with pets include:

- Aggravation of allergies and asthma caused by dander and fur or feathers

- Falling injuries. Tripping over pets, especially dogs causes more than 86,000 falls serious enough to prompt a trip to the emergency room each year in the United States.[46] Among elderly and disabled people, these falls have resulted in life-threatening injuries and broken bones.

- Injury, mauling, and sometimes death caused by pet bites and attacks

- Disease or parasites due to animal hygiene problems, lack of appropriate treatment, and undisciplined behavior (feces and urine)

- Stress caused by the behavior of animals

- Anxiety over who will care for the animal should the owner no longer be able to do so

Legislation

Treaties

The European Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals is a 1987 treaty of the Council of Europe – but accession to the treaty is open to all states in the world – to promote the welfare of pet animals and ensure minimum standards for their treatment and protection. It went into effect on 1 May 1992, and as of June 2020, it has been ratified by 24 states.[47]

National and local laws

States, cities, and towns in Western nations commonly enact local ordinances to limit the number or kind of pets a person may keep personally or for business purposes. Prohibited pets may be specific to certain breeds (such as pit bulls or Rottweilers), they may apply to general categories of animals (such as livestock, exotic animals, wild animals, and canid or felid hybrids), or they may simply be based on the animal's size. Additional or different maintenance rules and regulations may also apply. Condominium associations and owners of rental properties also commonly limit or forbid tenants' keeping of pets.

The keeping of animals as pets can cause concerns with regard to animal rights and welfare.[48][49][50] Pets have commonly been considered private property, owned by individual persons. However, many legal protections have existed (historically and today) with the intention of safeguarding pets' (and other animals') well-being.[51][52][53][54] Since the year 2000, a small but increasing number of jurisdictions in North America have enacted laws redefining pet's owners as guardians. Intentions have been characterized as simply changing attitudes and perceptions (but not legal consequences) to working toward legal personhood for pets themselves. Some veterinarians and breeders have opposed these moves. The question of pets' legal status can arise with concern to purchase or adoption, custody, divorce, estate and inheritance, injury, damage, and veterinary malpractice.[55][56][57][58]

In Belgium and the Netherlands, the government publishes white lists and black lists (called 'positive' and 'negative lists') with animal species that are designated to be appropriate to be kept as pets (positive) or not (negative). The Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy originally established its first positive list (positieflijst) per 1 February 2015 for a set of 100 mammals (including cats, dogs and production animals) deemed appropriate as pets on the recommendations of Wageningen University.[59] Parliamentary debates about such a pet list date back to the 1980s, with continuous disagreements about which species should be included and how the law should be enforced.[60] In January 2017, the white list was expanded to 123 species, while the black list that had been set up was expanded (with animals like the brown bear and two great kangaroo species) to contain 153 species unfit for petting, such as the armadillo, the sloth, the European hare and the wild boar.[61]

Environmental impact

Pets have a considerable environmental impact, especially in countries where they are common or held in high densities. For instance, the 163 million dogs and cats kept in the United States consume about 20% of the amount of dietary energy that humans do and an estimated 33% of the animal-derived energy.[62] They produce about 30% ± 13%, by mass, as much feces as Americans, and through their diet, constitute about 25–30% of the environmental impacts from animal production in terms of the use of land, water, fossil fuel, phosphate, and biocides. Dog and cat animal product consumption is responsible for the release of up to 64 ± 16 million tons CO2-equivalent methane and nitrous oxide, two powerful greenhouse gasses. Americans are the largest pet owners in the world, but pet ownership in the US has considerable environmental costs.[62]

Types

While many people have kept many different species of animals in captivity over the course of human history, only a relative few have been kept long enough to be considered domesticated. Other types of animals, notably monkeys, have never been domesticated but are still sold and kept as pets. There are also inanimate objects that have been kept as "pets", either as a form of a game or humorously (e.g. the Pet Rock or Chia Pet). Some wild animals are kept as pets, such as tigers, even though this is illegal. There is a market for illegal pets.

Domesticated

Domesticated pets are most common. A domesticated animal is a species that has been made fit for a human environment[63] by being consistently kept in captivity and selectively bred over a long enough period of time that it exhibits marked differences in behavior and appearance from its wild relatives. Domestication contrasts with taming, which is simply when an un-domesticated, wild animal has become tolerant of human presence, and perhaps, even enjoys it.

Mammals

Birds

- Companion parrots, like the budgie and cockatiel.

- Fowl, such as chickens, turkeys, ducks, geese and quails

- Columbines

- Passerines, namely finches and canaries

Arthropods

- Bees, such as Honey bees and Stingless bees

- Silk moth

Wild animals

Wild animals are kept as pets. The term “wild” in this context specifically applies to any species of animal which has not undergone a fundamental change in behavior to facilitate a close co-existence with humans. Some species may have been bred in captivity for a considerable length of time, but are still not recognized as domesticated.

Generally, wild animals are recognized as not suitable to keep as pets, and this practice is completely banned in many places. In other areas, certain species are allowed to be kept, and it is usually required for the owner to obtain a permit. It is considered animal cruelty by some, as most often, wild animals require precise and constant care that is very difficult to meet in captive conditions. Many large and instinctively aggressive animals are extremely dangerous, and numerous times have they killed their handlers.

History

Prehistory

Archaeology suggests that human ownership of dogs as pets may date back to at least 12,000 years ago.[64]

Ancient history

Ancient Greeks and Romans would openly grieve for the loss of a dog, evidenced by inscriptions left on tombstones commemorating their loss.[65] The surviving epitaphs dedicated to horses are more likely to reference a gratitude for the companionship that had come from war horses rather than race horses. The latter may have chiefly been commemorated as a way to further the owner's fame and glory.[66] In Ancient Egypt, dogs and baboons were kept as pets and buried with their owners. Dogs were given names, which is significant as Egyptians considered names to have magical properties.[67]

Victorian era: the rise of modern pet keeping

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth-century pet keeping in the modern sense gradually became accepted throughout Britain. Initially, aristocrats kept dogs for both companionship and hunting. Thus, pet keeping was a sign of elitism within society. By the nineteenth century, the rise of the middle class stimulated the development of pet keeping and it became inscribed within the bourgeois culture.[68]

Economy

As the popularity of pet-keeping in the modern sense rose during the Victorian era, animals became a fixture within urban culture as commodities and decorative objects.[69] Pet keeping generated a commercial opportunity for entrepreneurs. By the mid-nineteenth century, nearly twenty thousand street vendors in London dealt with live animals.[70] Also, the popularity of animals developed a demand for animal goods such as accessories and guides for pet keeping. Pet care developed into a big business by the end of the nineteenth century.[71]

Profiteers also sought out pet stealing as a means for economic gain. Utilizing the affection that owners had for their pets, professional dog stealers would capture animals and hold them for ransom.[72] The development of dog stealing reflects the increased value of pets. Pets gradually became defined as the property of their owners. Laws were created that punished offenders for their burglary.[73]

Social

Pets and animals also had social and cultural implications throughout the nineteenth century. The categorization of dogs by their breeds reflected the hierarchical, social order of the Victorian era. The pedigree of a dog represented the high status and lineage of their owners and reinforced social stratification.[74] Middle-class owners, however, valued the ability to associate with the upper-class through ownership of their pets. The ability to care for a pet signified respectability and the capability to be self-sufficient.[75] According to Harriet Ritvo, the identification of “elite animal and elite owner was not a confirmation of the owner’s status but a way of redefining it.”[76]

Entertainment

The popularity of dog and pet keeping generated animal fancy. Dog fanciers showed enthusiasm for owning pets, breeding dogs, and showing dogs in various shows. The first dog show took place on 28 June 1859 in Newcastle and focused mostly on sporting and hunting dogs.[77] However, pet owners produced an eagerness to demonstrate their pets as well as have an outlet to compete.[78] Thus, pet animals gradually were included within dog shows. The first large show, which would host one thousand entries, took place in Chelsea in 1863.[79] The Kennel Club was created in 1873 to ensure fairness and organization within dog shows. The development of the Stud Book by the Kennel Club defined policies, presented a national registry system of purebred dogs, and essentially institutionalized dog shows.[80]

Pet ownership by non-humans

Pet ownership by animals in the wild, as an analogue to the human phenomenon, has not been observed and is likely non-existent in nature.[81][82] One group of capuchin monkeys was observed appearing to care for a marmoset, a fellow New World monkey species, however observations of chimpanzees apparently "playing" with small animals like hyraxes have ended with the chimpanzees killing the animals and tossing the corpses around.[83]

A 2010 study states that human relationships with animals have an exclusive human cognitive component and that pet-keeping is a fundamental and ancient attribute of the human species. Anthropomorphism, or the projection of human feelings, thoughts and attributes on to animals, is a defining feature of human pet-keeping. The study identifies it as the same trait in evolution responsible for domestication and concern for animal welfare. It is estimated to have arisen at least 100,000 years before present (ybp) in Homo sapiens sapiens.[82]

It is debated whether this redirection of human nurturing behaviour towards non-human animals, in the form of pet-keeping, was maladaptive, due to being biologically costly, or whether it was positively selected for.[84][85][82] Two studies suggest that the human ability to domesticate and keep pets came from the same fundamental evolutionary trait and that this trait provided a material benefit in the form of domestication that was sufficiently adaptive to be positively selected for.[82][85]:300 A 2011 study suggests that the practical functions that some pets provide, such as assisting hunting or removing pests, could've resulted in enough evolutionary advantage to allow for the persistence of this behaviour in humans and outweigh the economic burden held by pets kept as playthings for immediate emotional rewards.[86] Two other studies suggest that the behaviour constitutes an error, side effect or misapplication of the evolved mechanisms responsible for human empathy and theory of mind to cover non-human animals which has not sufficiently impacted its evolutionary advantage in the long run.[85]:300

Animals in captivity, with the help of caretakers, have been considered to have owned "pets". Examples of this include Koko the gorilla and several pet cats, Tonda the orangutan and a pet cat and Tarra the elephant and a dog named Bella.[83]

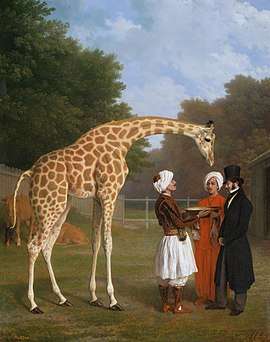

Pets in art

Katharine of Aragon with a monkey

Katharine of Aragon with a monkey The Girl with the Marmot by Jean-Honoré Fragonard

The Girl with the Marmot by Jean-Honoré Fragonard

- Young Lady with parrot by Édouard Manet 1866

- Young Lady with parrot by Édouard Manet 1866._Oudste_zuster_van_Louis_Metayer_Rijksmuseum_SK-A-2140.jpeg) Antoinette Metayer (1732–88) and her pet dog

Antoinette Metayer (1732–88) and her pet dog The Lady with an Ermine

The Lady with an Ermine Sir Henry Raeburn - Boy and Rabbit

Sir Henry Raeburn - Boy and Rabbit Eos, A Favorite Greyhound of Prince Albert

Eos, A Favorite Greyhound of Prince Albert A Neapolitan Woman

A Neapolitan Woman Signal, a Grey Arab, with a Groom in the Desert

Signal, a Grey Arab, with a Groom in the Desert Eduardo Leon Garrido. An Elegant Lady with her Dog

Eduardo Leon Garrido. An Elegant Lady with her Dog The Fireplace depicting a Pug, James Tissot

The Fireplace depicting a Pug, James Tissot

Rosa Bonheur - Portrait of William F. Cody

Rosa Bonheur - Portrait of William F. Cody

- Hunt

See also

|

|

|

References

- "Guardianship Movement". Pet Planet Health. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- Leslie, Be; Meek, Ah; Kawash, Gf; Mckeown, Db (April 1994). "An epidemiological investigation of pet ownership in Ontario" (Free full text). The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 35 (4): 218–22. ISSN 0008-5286. PMC 1686751. PMID 8076276.

- McRobbie, Linda Rodriguez (1 August 2017). "Should we stop keeping pets? Why more and more ethicists say yes". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- Tang, Ailin; Bradsher, Keith (22 October 2018). "The Trade War's Latest Casualties: China's Coddled Cats and Dogs". New York Times. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "China Pet population and ownership 2019 update". China Pet Market. 25 December 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Main_Page45 milioni gli animali domestici in Italia: 150.000 ogni anno vengono abbandonati". Il Messaggero. 22 September 2009. Archived from the original on 11 July 2013.

- "UK domestic cat and dog population larger than thought". University of Bristol. 6 February 2010.

- "More cat owners 'have degrees' than dog-lovers". BBC News Online. 6 February 2010.

- "Facts + Statistics: Pet statistics | III". www.iii.org. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- http://www.shea-online.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Animals%20in%20Healthcare%20Facilities.pdf Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- The Humane Society of the United States. "U.S. Pet Ownership Statistics". Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "U.S. Pet Ownership & Demographics Sourcebook (2012)". Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Daniel Halper (1 February 2013). "Animal Planet: Pets Outnumber Children 4 to 1 in America". The Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Susan Hayes. "What are the most popular pets around the world?". PetQuestions.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "Industry Statistics & Trends". American Pet Product Association. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "Plants and Your Cat". Cat Fanciers' Association. Archived from the original on 27 December 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- Langston, Cathy E. (1 January 2002). "Acute Renal Failure Caused by Lily Ingestion in Six Cats". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 220 (1): 49–52, 36. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.220.49. PMID 12680447.

- "These plants can be poisonous to dogs". Sunset Magazine. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- Klein, Dr Jerry; Dec 10, C. V. O.; Dec 10, 2018 | 2 Minutes; Minutes, 2018 | 2. "Are Poinsettias Poisonous to Dogs?". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 26 August 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Overweight Dogs". Pet Care. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA). Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Overweight Cats". Pet Care. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA). Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- Zelman, Joanna (23 February 2011). "Pet Obesity: Over Half Of U.S. Dogs And Cats Are Overweight, Study Says". Huffington Post. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Pets are a kid's best friend, right? Maybe not, study says". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- "The Health Benefits of Pets". US Government National Institute of Health. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- "Pets Are Good For Us—But Not In The Ways We Think They Are". National Geographic. 25 November 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- "Largest-Ever Study of Pets and Kids' Health Finds No Link; Findings Dispute Widely Held Beliefs About Positive Effects of Pet Ownership". RAND. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Reiman, Steve. "Therapy Dogs in the Long-Term Health Care Environment" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Whiteley, Ellen H. (1986). "The Healing Power of Pets". 258 (7). Saturday Evening Post. pp. 2–102. Retrieved 5 November 2006. Academic Search Elite. EBSCOhost. Polk Library, UW Oshkosh

- Bos, E.H.; Snippe, E.; de Jonge, P.; Jeronimus, B.F. (2016). "Preserving Subjective Wellbeing in the Face of Psychopathology: Buffering Effects of Personal Strengths and Resources". PLOS ONE. 11 (3): e0150867. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1150867B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150867. PMC 4786317. PMID 26963923.

- Asp, Karen (2005). "Volunteer Pets". Prevention. 57 (4): 176–78. Retrieved 5 November 2006. Academic Search Elite. EBSCOhost. Polk Library, UW Oshkosh

- Allen, K; Shykoff, Be; Izzo, Jl, Jr (1 October 2001). "Pet ownership, but not ace inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress". Hypertension. 38 (4): 815–20. doi:10.1161/hyp.38.4.815. ISSN 0194-911X. PMID 11641292. Archived from the original (Free full text) on 16 July 2012.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kingwell, Ba; Lomdahl, A; Anderson, Wp (October 2001). "Presence of a pet dog and human cardiovascular responses to mild mental stress". Clinical Autonomic Research. 11 (5): 313–7. doi:10.1007/BF02332977. ISSN 0959-9851. PMID 11758798.

- Wilson, Cc (October 1987). "Physiological responses of college students to a pet". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 175 (10): 606–12. doi:10.1097/00005053-198710000-00005. ISSN 0022-3018. PMID 3655768.

- Koivusilta, Leena K.; Ojanlatva, A; Baune, Bernhard (2006). Baune, Bernhard (ed.). "To Have or Not To Have a Pet for Better Health?". PLOS ONE. 1 (1): e109. Bibcode:2006PLoSO...1..109K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000109. PMC 1762431. PMID 17205113.

- Vormbrock, Jk; Grossberg, Jm (October 1988). "Cardiovascular effects of human–pet dog interactions". Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 11 (5): 509–17. doi:10.1007/BF00844843. ISSN 0160-7715. PMID 3236382.

- Dembicki, D and Anderson, J. 1996. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics. Volume 15 Issue 3, pages 15-31.

- Jodee (8 July 2010). "Want to Reduce Risk of Heart Disease? Get a Pet". Archived from the original on 27 March 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Friedmann E, Galik E, Thomas SA, Hall PS, Chung SY, McCune S. Evaluation of a Pet-Assisted Living Intervention for improving functional status in assisted living residents with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias.2015:30(3):276-289

- Parslow, Ruth; Jorm, Anthony; Christensen, Helen; Rodgers, Bryan; Jacomb, Patricia (January–February 2005). "Pet Ownership and Health in Older Adults". Gerontology. 40. 51 (1): 40–47. doi:10.1159/000081433. PMID 15591755.

- Farlex. "The Free Dictionary By Farlex". Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Reinman, Steve. "Therapy Dogs in the Long-Term Health Care Environment" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Huculak, Chad (4 October 2006). "Super Furry Animals". Edmonton: W7.. LexisNexis. Polk Library, UW Oshkosh. 5 November 2006.

- Bruck, Laura (1996). "Today's Ancillaries, Part 2: Art, music and pet therapy". Nursing Homes: Long-Term Care Management. 45 (7): 36. Retrieved 5 November 2006. Academic Search Elite. EBSCOhost. Polk Library, UW Oshkosh.

- Wood L, Martin K, Christian H, Nathan A, Lauritsen C, Houghton S, Kawachi I, McCune S. The pet factor - Companion animals as a conduit for getting to know people, friendship formation, and social support. PLoS One. 2015:10(4):e0122085

- Irvine, Leslie (2013). My Dog Always Eats First: Homeless People and Their Animals. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc.

- "In the Home, a Four-Legged Tripwire". The New York Times. 27 March 2009.

- "Chart of signatures and ratifications of Treaty 125. European Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals". Council of Europe. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "About Us". NhRP Website. Nonhuman Rights Project. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- "About IDA". IDA Website. In Defense of Animals. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- "Animal Rights Uncompromised: 'Pets'". PETA Website. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. 24 June 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Garner, Robert. "A Defense of a Broad Animal Protectionism," in Francione and Garner 2010, pp. 120–121.

- Francione, Gary Lawrence (1996). Rain without thunder: the ideology of the animal rights movement. ISBN 978-1-56639-461-1.

- Francione, Gary. Animals, Property, and the Law. Temple University Press, 1995.

- Garner 2005, p. 15; also see Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation, Random House, 1975; Regan, Tom. The Case for Animal Rights, University of California Press, 1983; Francione, Gary. Animals, Property, and the Law. Temple University Press, 1995; this paperback edition 2007.

- "Do You Live in a Guardian Community?". The Guardian Campaign. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Nolen, R. Scott (1 March 2005). "Now, it's the lawyers' turn". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- Chapman, Tamara (March–April 2005). "Owner or Guardian?" (PDF). Trends Magazine. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- Katz, Jon (5 March 2004). "Guarding the Guard Dogs?". Home / Heavy Petting: Pets & People. Slate. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- Sharon Dijksma (28 January 2015). "Kamerbrief invoering huisdierenlijst zoogdiersoorten". Rijksoverheid.nl (in Dutch). Dutch Government. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Een rendier mag dan weer wel". Trouw (in Dutch). 3 December 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Rijksoverheid / ANP (31 January 2017). "Lijst 2017 bekend: welke dieren mag jij als huisdier houden?" (in Dutch). BNNVARA. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Okin, Gregory S. (2 August 2017). "Environmental impacts of food consumption by dogs and cats". PLOS ONE. 12 (8): e0181301. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1281301O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181301. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5540283. PMID 28767700.

- Farlex. "The Free Dictionary by Farlex". Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1995). "Origins of the dog: domestication and early history". In Serpell, James (ed.). The domestic dog: its evolution, behaviour and interactions with people. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9780521425377.

- Messenger, Stephen (13 June 2014). "9 Touching Epitaphs Ancient Greeks And Romans Wrote For Their Deceased Dogs". The Dodo. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Anthony L. Podberscek; Elizabeth S. Paul; James A. Serpell (21 July 2005). Companion Animals and Us: Exploring the Relationships Between People and Pets. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-01771-8.

- Mertz, Barbara (1978). Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt. Dodd Mead.

- Amato, Sarah (2015). Beastly Possession: Animals in the Victorian Consumer Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 25.

- Amato, Sarah (2015). Beastly Possessions: Animals in Victorian Consumer Culture. University of Toronto Press. p. 6.

- Ritvo, Harriet (1987). The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 86.

- Amato, Sarah (2015). Beastly Possession: Animals in Victorian Consumer Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 48.

- Philo, Chris (1989). Animal Space, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Animal Relations. Routledge. pp. 38–389.

- Philo, Chris (1989). Animal Space, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Animal Relations. Routledge. p. 41.

- Amato, Sarah (2015). Beastly Possession: Animals in Victorian Consumer Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 55.

- Amato, Sarah (2015). Beastly Possession: Animals in Victorian Consumer Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 10.

- Ritvo, Harriet (1987). The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Era. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 104.

- Ritvo, Harriet (1987). The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in Victorian Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 7–8.

- Ritvo, Harriet (1987). The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 98.

- Ritvo, Harriet (1987). The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 66.

- Ritvo, Harriet (1987). The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 104.

- Herzog, Harold A. (2014). "Biology, Culture, and the Origins of Pet-Keeping". Animal Behavior and Cognition. 1 (3): 296. doi:10.12966/abc.08.06.2014. ISSN 2372-4323.

- Bradshaw, J. W. S.; Paul, E. S. (2010). "Could empathy for animals have been an adaptation in the evolution of Homo sapiens?" (PDF). Animal Welfare. 19 (S): 107–112. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- "Are Humans the Only Animals That Keep Pets?".

- Clutton-Brock, Juliet (30 October 2014). The Walking Larder: Patterns of Domestication, Pastoralism, and Predation. Routledge. pp. 16, 19. ISBN 9781317598381.

- Salmon, Catherine; Shackelford, Todd K. (27 May 2011). The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Family Psychology. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 299. ISBN 9780195396690.

- Gray, Peter B.; Young, Sharon M. (1 March 2011). "Human–Pet Dynamics in Cross-Cultural Perspective". Anthrozoös. 24 (1): 18, 27. doi:10.2752/175303711X12923300467285. ISSN 0892-7936.

Further reading

- David Grimm (2015). Citizen Canine: Our Evolving Relationship with Cats and Dogs. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1610395502.

External links

- Companion Animal Demographics in the United States: A Historical Perspective from The State of the Animals II: 2003

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: How to choose your pet and take care of it |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pets. |

| Look up pet in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |