Welsh cuisine

Welsh cuisine encompasses the cooking traditions and practices associated with the country of Wales and the Welsh people. While there are many dishes that can be considered Welsh due to their ingredients and/or history, dishes such as cawl, Welsh rarebit, laverbread, Welsh cakes, bara brith and the Glamorgan sausage have all been regarded as symbols of Welsh food. Some variation in dishes exists across the country, with notable differences existing in the Gower Peninsula, an historically isolated rural area which developed self-sufficiency in food production. See Cuisine of Gower.

| British cuisine |

|---|

| National cuisines |

| Overseas/Fusion cuisine |

|

|

While some culinary practices and dishes have been imported from its British neighbors, uniquely Welsh cuisine grew principally from the lives of Welsh working people, largely as a result of their isolation from outside culinary influences and the need to produce food based on the limited ingredients they could produce or afford. Welsh Celts and their more recent Welsh descendants originally practiced transhumance, moving their cattle to higher elevations in the summer and back to their home base in the winter. Once they settled to homesteads, a family would have generally eaten meat from a pig primarily, keeping a cow for dairy products.

Sheep farming is practiced extensively in Wales, with lamb and mutton being the meats most traditionally associated with the country. Beef and dairy cattle are also raised widely, and there is a strong fishing culture. Fisheries and commercial fishing are common and seafood features widely in Welsh cuisine.

Vegetables, beyond cabbages and leeks, were historically rare and the leek became a significant component of many dishes. It has been a national symbol of Wales for at least 400 years and Shakespeare refers to the Welsh custom of wearing a leek in Henry V.

Since the 1970s, the number of restaurants and gastropubs in Wales has increased significantly[1] and there are currently five Michelin starred restaurants located in the country.[2]

History

Bobby Freeman in First Catch Your Peacock: The Classic Guide to Welsh Food[3]

There are few written records of traditional Welsh foods; recipes were instead held within families and passed down orally between the women of the family.[3] The lack of records was highlighted by Mati Thomas in 1928, who made a unique collection of 18th century "Welsh Culinary Recipes" as an award-winning Eisteddfod entry.[3]

Those with the skills and inclination to write Welsh recipes, the upper classes, conformed to English styles and therefore would not have run their houses with traditional Welsh cuisine.[4] Upper-class households would take on any English fashions, even adopting English names.[5] The traditional cookery of Wales originates from the daily meals of peasant folk, unlike other cultures where meals often started in the kitchens of the gentry and would be adapted.[4]

_Kissing_couple.jpg)

Historically the King of the Welsh people would travel, with his court, in a circuit, demanding tribute in the form of food from communities they visited as they went. The tribute was codified in the Laws of Hywel Dda, showing that people lived on beer, bread, meat and dairy products, with few vegetables beyond cabbages and leeks. The laws show how much value was put on different parts of Welsh life at the time, for example that wealth was measured in cattle;[5] they also show that the court included hunters, who would be restricted to seasonal hunting sessions.[6]

Towards the start of the 11th century, Welsh society started to build settlements.[7] Food would be cooked in a single cauldron over an open fire on the floor; it would likely be reheated and topped up with fresh ingredients over a number of days. Some dishes could be cooked on a bakestone, a flat stone which could be placed above a fire to heat it evenly.[5]

Gerald of Wales, chaplain to Henry II, wrote after an 1188 tour of Wales, "The whole population lives almost entirely on oats and the produce of their herds, milk, cheese and butter. You must not expect a variety of dishes from a Welsh kitchen, and there are no highly-seasoned titbits to whet your appetite."[5] The medieval Welsh used thyme, savory, and mint in the kitchen, but in general herbs were much more likely to be used for medicinal purposes than culinary ones.[8]

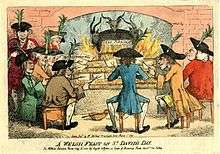

Towards the end of the 18th century, Welsh land owners divided up the land to allow for tenant-based farming. Each small holding would include vegetable crops, as well as a cow, pigs and a few chickens.[6] The 18th and 19th centuries were a time of unrest for the Welsh people. The Welsh food riots began in 1740, when colliers blamed the lack of food on problems in the supply, and continued throughout Wales as a whole.[9] The worst riots happened in the 1790s after a grain shortage, which coincided with political upheaval in the form of forced military service and high taxes on the roads, leaving farmers unable to make a profit.[10] As a result of riots by colliers in the mid 1790s,[11] magistrates in Glamorgan sold the rioters corn at a reduced price. At the same time they also requested military assistance from the government to stop further rioting.[12] Due to the close-knit nature of the poor communities, and the slightly higher status of the farmers above the labourers,[13] the rioters generally blamed the farmers and corn merchants, rather than the gentry.[14]

The majority of food riots had ended by 1801, and there were certain political undertones to the actions, though lack of leadership meant that little came of it.[15][16] By the 1870s, 60% of Wales was owned by 570 families, most of whom did no farming. Instead, they employed workers, who were forced to vote Tory or lose their jobs.[17]

Around the end of the 19th century, the increase in coal mining and steel works around Wales led to the immigration of Italian workers.[18] The workers brought families who integrated their culture into Welsh society, bringing with them Italian ice cream and Italian cafes, now a staple of Welsh society.[19]

In the 1960s, isolated communities were unable to access produce that the majority of Britain would such as peppers or aubergines.[20] Artisan Welsh produce was limited or non-existent, farms rarely made their own cheese, and Welsh wine was of poor quality. By the 1990s, historical Welsh foods were going through a revival. Farmers' markets became more popular, Welsh organic vegetables and farm-made cheese started to appear in supermarkets.[20] Other modern Welsh characteristics are more subtle, such as supermarkets offering salty butters and laverbread or butchers labelling beef skirt as 'cawl meat'.[21]

Restaurants are promoting the quality of Welsh ingredients, encouraging people to purchase Welsh produce and creating new dishes using them. This has meant that Welsh products can find their way into the higher-priced delicatessens of London or North America. However, the regular diet of Welsh people has been more influenced by India, China and America. The most popular dish is chicken tikka masala, followed by burgers or chow mein. As a result of the popularity of these sorts of foods, Wales has the highest fat consumption in Britain, and the highest levels of obesity.[22]

Regional variations

There are some variations in the foods that are eaten around the different areas of Wales. These variations trace their roots back to medieval cooking. Ingredients were historically limited by what could be grown; the wetter climate in highland areas meant that crops were restricted to oats, whilst the more fertile lowland areas allowed the growth of barley or wheat.[6] Coastal inhabitants were more likely to include seafood or seaweed in their meals, whilst those living inland would supplement their farmed cereals with the seeds of land weeds to ensure there was enough to eat.[23]

The invasions of the Romans and Normans also had an effect on the fertile areas which were conquered. The people there learned more "sophisticated eating habits". Conversely those who remained in wilder areas kept the traditional approaches to cooking; tools such as the pot crane continued to be used as late as the 20th century.[24]

The only region that has a significant difference from the rest of Wales is the Gower peninsula, whose lack of land transport links left it isolated. Instead it was strongly influenced by Somerset and Devon on the other side of the Bristol Channel. Dishes such as whitepot and ingredients such as pumpkin, rare elsewhere in Wales, became commonplace in Gower.[25]

Produce

Welsh food can be better traced through the history of its foodstuffs than through the dishes.[26]

Meat and fish

There a number of local Welsh breeds of cow, including the Welsh Black, a breed which dates back to at least 1874. Cattle farming accounts for the majority of agricultural output in Wales—in 1998 the production of beef contributed 23% of Welsh agricultural output, whilst in 2002 25% of agricultural output was in the production of dairy products. Welsh beef has a European Union Protected Geographical Indicator, so it must be wholly reared and slaughtered in Wales.[27]

Pigs were the primary meat eaten by early Welsh folk, which could be preserved easily by salting.[28] By 1700, there were a number of different Welsh breeds of pig, with long snouts and thin backs, generally light coloured, but some were dark or spotted. Today, pigs in Wales are either farmed intensively, using the white Welsh pig or Landrace pig, or extensively, where Saddleback pig, Welsh pig or crossbreeds are farmed.[29]

The Welsh uplands were most suited to grazing animals such as sheep and goats, and the animals became associated with Wales. Sheep-farming on a large scale was introduced by Cistercian monks, largely for wool, but also for meat.[30] By the start of the 16th century Welsh mutton was popular in the rest of the UK.[31] Once modern synthetic fibres became more popular than wool, Welsh sheep were raised almost exclusively for meat. Towards the end of the 20th century, there were more than 11 million sheep in Wales.[30] The most popular breed of sheep is the Welsh Mountain sheep which is notably smaller than other breeds but better-suited to the Welsh landscape and only rears one lamb, rather than the lowland breeds which rear two or more; the mountain sheep are regarded as having more flavoursome meat.[31][30] Welsh farmers have started using scientific methods, such as artificial insemination or using ultrasound to scan a sheep's depth of fat, to improve the quality of their meat.[30]

Coastal areas of Wales, and those near rivers, produce many different forms of fish and shellfish. Traditional fishing methods, such as wade netting for salmon, remained in place for 2,000 years. Welsh coracles, simple boats made of a willow frame and covered in animal hides, were noted by Romans and were still in use in the 20th century. Once landed, fish would generally be wind-dried and smoked, or cured with salt.[32]

Herring, a fish which takes well to salting, became a well established catch; the busiest harbour was Aberystwyth, which reportedly took up to 1,000 barrels of herring in a single night in 1724. Many other villages also fished for herring, generally between late August and December.[33] Herring, along with mackerel, trout, salmon and sea trout, were the main fishes found in Welsh cuisine.[34] Salmon was abundant and therefore a staple for the poor.[35] Trout, which would dry out quickly when cooked, would be wrapped in leek leaves for cooking, or covered in bacon or oatmeal.[36] Many fish would be served with fennel, which grew wild in abundance in Wales.[37]

Lobster fishing was done on a small scale especially in Cardigan Bay, but was reserved almost exclusively for export. Welsh fisherman would be more likely to eat the less profitable crabs.[34] Cockles have been harvested since Roman times and are still harvested in a traditional manner with a hand rake and scraper.[38] Cockle picking still happens in the Gower peninsula, but due to the difficulty in getting licences and reduced yield, villages near the Carmarthen Bay no longer gather them.[33]

Dairy products

As cattle were the basis of Celtic wealth, butter and cheese were generally made from cows' milk. The Celts were amongst the earliest producers of butter in Britain, and for hundreds of years after the Romans left the country, butter was the primary cooking medium and basis for sauces. Salt was an important ingredient in Welsh butter, but also in early Welsh cheeses, which would sit in brine during the cheesemaking process. [39]

The Welsh were also early adopters of roasting cheese. An early incarnation of Welsh rarebit was being made in medieval times, and by the middle of the 15th century rarebit was considered a national dish. The acid soil of Wales meant that the milk produced by their cattle created a soft cheese, which was not as good for roasting, so Welsh people would trade for harder cheeses such as Cheddar.[40]

The best-known Welsh cheese is Caerphilly, named in 1831 but made long before that. Originally a method for storing excess milk until it could be brought to market, it was a moist cheese that would not last very long. Production of the cheese was halted due to milk rationing after World War II, although it was still made in England. There, the cheese was produced very quickly and sold early in its maturation process, creating a dryer cheese. In the 1970s, production of Caerphilly returned to Wales and over the following few decades a variety of new cheeses have also been produced in Wales.[41][42]

Cereals

As far back as the Iron Age, Welsh folk were using wild cereals to create a coarse bread. By the time the Romans invaded, Celtic skills with bread had progressed to the point that white or brown breads could be produced. The Roman invasion led to many Welsh people moving to the less hospitable uplands, where the only cereal crops which could be grown were oats, barley and rye. Oat and barley breads were the main breads eaten in Wales up until the 19th century, with rye bread created for medicinal purposes. Oats were used to bulk out meat or meat and vegetable stews, also known as pottage.[43]

The Welsh also created a dish called llymru, finely ground oatmeal soaked in water for a long time before boiling until it solidified. This blancmange-styled dish became so popular outside Wales that it got a new name, flummery, as the English could not pronounce the original. A similar dish, sucan, was made with less finely ground oatmeal, making a coarser product.[44]

Vegetables

Celtic law made specific provision with regard to cabbages and leeks, stating that they should be enclosed by fences for protection against wandering cattle. The two green vegetables were the only ones mentioned specifically in the laws, though uncultivated plants were still likely to be used in their cooking.[45] The leek went on to be so important to Welsh cuisine—found in many symbolic dishes including cawl and Glamorgan sausage—that it became the country's national vegetable.[46]

Potatoes were slow to be adopted amongst Welsh folk, despite being introduced to the UK in the 16th century; only in the early 18th century did they become a Welsh staple, due to grain failures.[47] Once the potato did become a staple, it was quickly found in Welsh dishes such as cawl, and traditions grew around their use. One tradition, which was still in place at the start of World War II, was that villagers could plant an 80-yard (73-metre) row of potatoes in a neighbouring farmer's field for each labourer the household could provide at the time of harvest.[48]

Welsh dishes

Whilst there are many dishes that can be considered Welsh due to their ingredients, there are some which are quintessentially Welsh. Dishes such as cawl, Welsh rarebit, laverbread, Welsh cakes, bara brith (literally "fruit bread") or the Glamorgan sausage have all been regarded as symbols of Welsh food.[46]

Cawl, pronounced in a similar way to the English word "cowl",[49] can be regarded as Wales' national dish.[50] Dating back to the 11th century,[50] originally it was a simple broth of meat (most likely bacon) and vegetables, it could be cooked slowly over the course of the day whilst the family was out working the fields.[51] It could be made in stages, over a number of days, first by making a meat stock, then by adding the vegetables on the following day.[50] Once cooked, the fat could be skimmed from the top of the pot, then it would be served as two separate dishes, first as a soup, then as a stew.[52] Leftovers could be topped up with fresh vegetables, sometimes over the course of weeks.[53] During the 18th and 19th centuries, the amount of meat used in the broth was minimal; instead it was bulked out with potatoes.[23] Today, cawl would be much more likely to include beef or lamb for the meat,[54] and may be served with plain oatmeal dumplings or currant dumplings known as trollies.[54] Traditionally cawl would be eaten with a "specially-carved wooden spoon" and eaten from a wooden bowl.[51]

The predilection of the Welsh for roasted cheese led to the dish of Welsh rarebit, or Welsh rabbit, seasoned melted cheese poured over toasted bread.[55] The cheese would need to be a harder one, such as cheddar or similar. Referred to as Welsh rabbit as early as 1725, the name is not similar to the Welsh term caws pobi. Welsh folk rarely ate rabbit due to the cost and as land owners would not allow rabbit hunting, so the term is more likely a slur on the Welsh.[53][56][57] The name evolved from rabbit to rarebit, possibly to remove the slur from Welsh cuisine or due to simple reinterpretation of the word to make menus more pleasant.[58]

Laverbread, or Bara Lawr, is a Welsh speciality. It is made by cooking porphyra seaweed slowly for up to ten hours[59] until it becomes a puree known as laver. The seaweed can also be cooked with oatmeal to make laverbread. It can be served with bacon and cockles as a breakfast dish,[60] or fried in to small patties.[61] Today, laverbread is commercially produced by washing in water, cooking for about 5 hours before chopping, salting and packaging.[62]

The Glamorgan sausage is a Welsh vegetarian sausage. It contains no meat or skin, instead it is made with cheese, generally Caerphilly, but sometimes cheddar, along with leek or spring onion.[63] This mixture is then coated in breadcrumbs and rolled into a sausage shape before cooking.[46][64] Glamorgan sausages date back to at least the early 19th century, at which point the sausages would have contained pork fat.[65][66]

Welsh cakes, or pice ar y maen meaning "cakes on the stone", are small round spiced cakes, traditionally cooked on a bakestone, but more recently on a griddle. Once cooked, they can be eaten hot or cold, on their own or topped either with sugar or butter.[67] The dough which is mixed with raisins, sultanas and sometimes currants,[68] is similar to shortbread, meaning they can have the consistency of biscuits when cooked on the griddle, and slightly more like a cake when cooked in the oven.[69]

Bara brith is a fruit loaf originating from rural Wales, where they used a mortar and pestle to grind the fresh sweet spices.[70] Historically it was made with yeast and butter, though recently it is likely to be made with bicarbonate of soda and margarine.[71] The fruit included would be dried raisins, currants and candied peel,[72] which would be soaked in cold tea before cooking.[71] Generally served sliced with butter during afternoon tea,[73] it is often known as Welsh tea bread.[72] Bara Brith translates to "speckled bread",[71] but it is also known as teisen dorth in South Wales, where sultanas are included in the recipe,[74] or as torta negra when Welsh settlers brought it to Argentina.[72]

Cawl

Cawl- Welsh rarebit

- Laverbread

Glamorgan sausage

Glamorgan sausage Welsh cakes

Welsh cakes.jpg) Bara Brith

Bara Brith Tatws Popty

Tatws Popty- Tatws Pum Munud

Beverages

Wine and beer, especially of the home-made varieties, were central to socialising in Wales, as they were in England. This remained the case even when tea gained popularity in England, supplanting the home-made alcohol.[75] Beer is now the national drink of Wales, although Welsh beers never gained the status of other British beers, such as stout or English ales. This was in part due to the breweries keeping promotion of their products to a minimum so as not to upset the temperance movement in Wales.[76]

The temperance movement remained a strong influence though, and when new breweries were set up, the outcry led to the Welsh Sunday Closing Act in 1881, an act that forced the closure of public houses in Wales on a Sunday.[76] Wales' passion for beer remained; the Wrexham Lager Beer Company opened in 1881, as the first lager producer in Britain. The Felinfoel Brewery made a deal with the local tin works and became the first brewery in Europe to put beer in cans.[76]

The Welsh also have a history of producing whisky, in a similar manner to other Celtic people such as the Irish or Scottish but on a smaller scale. Distillation began for commercial purposes before 1750, by families who went on to emigrate to America and help found the Kentucky Whiskey industry. Always a niche industry, by the late 19th century, the main whisky production in Wales was at Frongoch near Bala, Gwynedd. The distillery was bought by Scottish whisky companies and closed in 1910 when they were attempting to establish brands in England.[77][78] In 1998 the Welsh Whisky Company, now known as Penderyn, was formed and whisky production began at Penderyn, Rhondda Cynon Taf in 2000. Penderyn single malt whisky was the first whisky commercially produced in Wales for a century and went on sale in 2004. The company also produces Merlyn Cream Liqueur, Five Vodka and Brecon Gin.[79]

Welsh vineyards were first planted by Romans, but in the 1970s, modern vineyards were planted in South Wales with the intention of creating Welsh wine. Despite a slow start, by 2005 Wales had 20 vineyards, producing 100,000 bottles a year, primarily white wines, but also a few reds.[80][81] According to the Wine Standards Board, by September 2015, there were 22 operational vineyards in Wales.[82] and there were almost 40 hectares (99 acres) of vines planted in Wales.[83]

By 2005 the Welsh bottled water industry was worth as much as £100m. Popular brands include Brecon Carreg, Tŷ Nant, Princes Gate and Pant Du.[84][85][86][87][88]

Eating out

The number of restaurants in Wales has significantly increased since the 1960s, when the country had very few notable places to eat out.[20] Today, Wales is no longer considered a "gastronomic desert";[89] as of 2016, it has five Michelin starred restaurants and[90] other award systems such as TripAdvisor and the AA have included Welsh restaurants in their lists. The most significant increase in restaurants has been at the high end, but there has been growth and improvement in quality across the whole range of Welsh eateries.[89]

Many Welsh restaurants showcase their Welsh ingredients, creating new dishes from them.[89] There has also been a rise in Asian cuisine in Wales, especially that of Indian, Chinese, Thai, Indonesian and Japanese, with a preference for spicier foods.[89] Finally there has been a significant rise in "gastropubs", as there has around the United Kingdom.

See also

References

- Freeman, Bobby (1996). First catch your peacock: her classic guide to Welsh food (Rev. paperback ed.). Talybont, Ceredigion: Y Lolfa. pp. 8, 52–53. ISBN 0862433150.

- "2016 Michelin Award summary" (PDF). Michelin. 2016. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- Freeman 1996, p. 14.

- Freeman 1996, p. 15.

- Davidson 2014, p. 858.

- Freeman 1996, p. 18.

- Freeman 1996, p. 35.

- Freeman 1996, p. 48.

- Ireland, Richard (2015). "The eighteenth century". Land of White Gloves?: A History of Crime and Punishment in Wales Volume 4 of History of Crime in the UK and Ireland. Routledge. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-135-08941-2. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Gower, Jon (2012). "Chapter 19: Revolt and unrest". The Story of Wales. Random House. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-4464-1710-2. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Bohstedt 2016, p. 174.

- Bohstedt 2016, p. 181.

- Howell, D. W.; Baber, C. (1993). "Wales". In Thompson, F. M. L (ed.). The Cambridge Social History of Britain, 1750–1950, Volume 1 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 283–296. ISBN 978-0-521-43816-2. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Kearney, Hugh (1995). "The Britannic melting pot". The British Isles: A History of Four Nations (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-521-48488-6. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Thomas, J. E. (2011). "An intellectual basis of protest?". Social Disorder in Britain 1750–1850: The Power of the Gentry, Radicalism and Religion in Wales. I. B. Tauris. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-1-84885-503-8. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Jenkins, Philip (2014). "Welsh politics in the Eighteenth Century". A History of Modern Wales 1536–1990 (Revised ed.). Routledge. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-317-87269-6. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Heyck 2002, p. 44.

- Richards, Greg (2003). Hjalager, Anne-Mette (ed.). Tourism and Gastronomy. Routledge. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-134-48059-3.

- Loury, Glenn C.; Modood, Tariq; Teles, Steven M. Ethnicity, Social Mobility, and Public Policy: Comparing the USA and UK. Cambridge University Press. p. 415. ISBN 978-1-139-44365-4.

- Freeman 1996, p. 8.

- Freeman 1996, p. 51.

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Baines, M. Food and drink (Online ed.). The Welsh Academy Encyclopedia of Wales.

- Freeman 1996, p. 20.

- Freeman 1996, pp. 20–21.

- Freeman 1996, p. 22.

- Freeman 1996, p. 26.

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Baines, M. Cattle (Online ed.). The Welsh Academy encyclopedia of Wales.

- Freeman 1996, pp. 35–36.

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Baines, M. Pigs (Online ed.). The Welsh Academy encyclopedia of Wales.

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Baines, M. Sheep (Online ed.). The Welsh Academy encyclopedia of Wales.

- Freeman 1996, pp. 37–38.

- Freeman 1996, p. 40.

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Baines, M. Fish and Fishing (Online ed.). The Welsh Academy encyclopedia of Wales.

- Freeman 1996, pp. 41–42.

- Freeman 1996, p. 61.

- Freeman 1996, p. 55.

- Freeman 1996, p. 67.

- Freeman 1996, p. 43.

- Freeman 1996, pp. 30–31.

- Freeman 1996, p. 31.

- Wilson, Bee (9 October 2011). "Caerphilly: the old version is the best". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- Davies & Jenkins 2008, p. 137.

- Freeman 1996, pp. 27–28.

- Freeman 1996, p. 29.

- Freeman 1996, p. 44.

- Minahan, James (2009). The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems [2 Volumes] (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 572. ISBN 978-0-313-34497-8.

- Freeman 1996, p. 45.

- Freeman 1996, pp. 46–47.

- Freeman 1996, p. 106.

- Webb 2012, p. 68.

- Davidson 2014, p. 224.

- Cotter, Charis (2008). "Meats". One Thousand and One Foods (illustrated ed.). Anova Books. p. 545. ISBN 978-1-86205-785-2.

- Breverton, Terry (2012). "Food". Wales: A Historical Companion. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-0990-4.

- Davidson 2014, p. 154.

- National Trust (2007). Gentleman's Relish: A Compendium of English Culinary Oddities (illustrated ed.). Anova Books. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-905400-55-3.

- Grumley-Grennan, Tony (2009). The Fat Man's Food & Drink Compendium. ISBN 978-0-9538922-3-5.

- Imholtz, August; Tannenbaum, Alison; Carr, A. E. K (2009). Alice Eats Wonderland (Illustrated, annotated ed.). Applewood Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4290-9106-0.

- Reich, Herb (2013). Don't You Believe It!: Exposing the Myths Behind Commonly Believed Fallacies. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-62873-324-2.

- Hadoke, Mike; Kerndter, Fritz (2004). Langenscheidt Praxiswörterbuch Gastronomie: Englisch-Deutsch, Deutsch-Englisch. Langenscheidt Fachverlag. p. 90. ISBN 978-3-86117-199-7.

- O'Connor, Kaori (December 2009). "THE SECRET HISTORY OF 'THE WEED OF HIRAETH': LAVERBREAD, IDENTITY, AND MUSEUMS IN WALES". Journal of Museum Ethnography. Museum Ethnographers Group (22): 83. JSTOR 41417139.

- Lewis-Stempel, John (2012). Foraging The Essential Guide to Free Wild Food. London: Hachette UK. ISBN 978-0-7160-2321-0.

- Johansen, Mariela; Mouritsen, Jonas Drotner; Mouritsen, Ole G (2013). Seaweeds : edible, available & sustainable (illustrated ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-226-04436-1. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- Ayto, John (2012). The Diner's Dictionary: Word Origins of Food and Drink (illustrated ed.). OUP Oxford. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-19-964024-9.

- Allen, Gary (2015). Sausage: A Global History. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-555-4.

- "What? Pork in a Glamorgan sausage!". South Wales Echo. 29 October 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2016 – via News Bank.

- "Putting pork in 'veggie' sausage". South Wales Echo. 31 October 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2016 – via News Bank.

- Davidson 2014, p. 365.

- Roufs, Timothy G.; Roufs, Kathleen Smyth (2014). Sweet Treats around the World: An Encyclopedia of Food and Culture: An Encyclopedia of Food and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 375. ISBN 978-1-61069-221-2.

- Ayto, John (2012). The Diner's Dictionary: Word Origins of Food and Drink (illustrated ed.). OUP Oxford. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-19-964024-9.

- Hensperger, Beth; Williams, Chuck (2002). "Welsh Bara Brith". In Williams, Chuck (ed.). Williams-Sonoma Collection: Bread (Illustrated ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-7432-2837-4. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Freeman 1996, p. 102.

- Bain, Andrew (2009). Lonely Planet's 1000 Ultimate Experiences (Illustrated ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-74179-945-3. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Davidson 2014, p. 62.

- Webb 2012, p. 74.

- Freeman 1996, p. 47.

- Davies & Jenkins 2008, p. 57.

- Freeman 1996, pp. 263–264.

- Davies & Jenkins 2008, pp. 947–948.

- "Rebirth of Welsh whisky spirit". BBC News Online. 8 May 2008.

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Baines, M. Vineyards (Online ed.). The Welsh Academy encyclopedia of Wales.

- Freeman 1996, p. 19.

- "UK Vineyard Register: Full list of commercial vineyards, Updated September 2015" (PDF). www.food.gov.uk/. 19 April 2015.

- "UK Vineyard Register, Food Standards Agency". Food.gov.uk. 19 April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- "Wales makes a splash in bottled water market". Wales Online. 31 March 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- "The History Of Tŷ Nant – Tŷ Nant". Tynant.com. 24 January 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- "Our Awards - Brecon Carreg". Breconwater.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- "Princes Gate Spring Water - Bottled Water and Water Coolers in Wales". Princesgate.com. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- "Gogledd Cymru". Pant Du. 13 January 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- Freeman 1996, pp. 52–53.

- "2016 Michelin Award summary" (PDF). Michelin. 2016. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

Bibliography

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Colquhoun, Kate (2008) [2007]. Taste: The Story of Britain through its Cooking. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-7475-9306-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Freeman, Bobby (1996). First catch your peacock : the classic guide to Welsh food (Rev. paperback ed.). Talybont, Ceredigion: Y Lolfa. ISBN 0-86243-315-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davidson, Alan (2014). Jaine, Tom (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heyck, Thomas William (2002). A History of the Peoples of the British Isles, Volume 3 (Illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-30233-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bohstedt, John (2016). The Politics of Provisions: Food Riots, Moral Economy, and Market Transition in England, C. 1550–1850. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-02020-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Webb, Andrew (2012). Food Britannia. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4090-2222-0. Retrieved 5 April 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Welsh Agricultural Statistics from the Welsh Assembly.

- Culture UK Welsh Food

- Welsh Food on Wales.com