Drink

A drink (or beverage) is a liquid intended for human consumption. In addition to their basic function of satisfying thirst, drinks play important roles in human culture. Common types of drinks include plain drinking water, milk, coffee, tea, hot chocolate, juice and soft drinks. In addition, alcoholic drinks such as wine, beer, and liquor, which contain the drug ethanol, have been part of human culture for more than 8,000 years.

Non-alcoholic drinks often signify drinks that would normally contain alcohol, such as beer and wine, but are made with a sufficiently low concentration of alcohol by volume. The category includes drinks that have undergone an alcohol removal process such as non-alcoholic beers and de-alcoholized wines.

Biology

When the human body becomes dehydrated, it experiences thirst. This craving of fluids results in an instinctive need to drink. Thirst is regulated by the hypothalamus in response to subtle changes in the body's electrolyte levels, and also as a result of changes in the volume of blood circulating. The complete elimination of drinks, that is, water, from the body will result in death faster than the removal of any other substance.[1] Water and milk have been basic drinks throughout history.[1] As water is essential for life, it has also been the carrier of many diseases.[2]

As society developed, techniques were discovered to create alcoholic drinks from the plants that were available in different areas. The earliest archaeological evidence of wine production yet found has been at sites in Georgia (c. 6000 BCE)[3][4][5] and Iran (c. 5000 BCE).[6] Beer may have been known in Neolithic Europe as far back as 3000 BCE,[7] and was mainly brewed on a domestic scale.[8] The invention of beer (and bread) has been argued to be responsible for humanity's ability to develop technology and build civilization.[9][10][11] Tea likely originated in Yunnan, China during the Shang Dynasty (1500 BCE–1046 BCE) as a medicinal drink.[12]

History

Drinking has been a large part of socialising throughout the centuries. In Ancient Greece, a social gathering for the purpose of drinking was known as a symposium, where watered down wine would be drunk. The purpose of these gatherings could be anything from serious discussions to direct indulgence. In Ancient Rome, a similar concept of a convivium took place regularly.

Many early societies considered alcohol a gift from the gods,[13] leading to the creation of gods such as Dionysus. Other religions forbid, discourage, or restrict the drinking of alcoholic drinks for various reasons. In some regions with a dominant religion the production, sale, and consumption of alcoholic drinks is forbidden to everybody, regardless of religion.

Toasting is a method of honouring a person or wishing good will by taking a drink.[13] Another tradition is that of the loving cup, at weddings or other celebrations such as sports victories a group will share a drink in a large receptacle, shared by everyone until empty.[13]

In East Africa and Yemen, coffee was used in native religious ceremonies. As these ceremonies conflicted with the beliefs of the Christian church, the Ethiopian Church banned the secular consumption of coffee until the reign of Emperor Menelik II.[14] The drink was also banned in Ottoman Turkey during the 17th century for political reasons[15] and was associated with rebellious political activities in Europe.

Production

A drink is a form of liquid which has been prepared for human consumption. The preparation can include a number of different steps, some prior to transport, others immediately prior to consumption.

Purification of water

Water is the chief constituent in all drinks, and the primary ingredient in most. Water is purified prior to drinking. Methods for purification include filtration and the addition of chemicals, such as chlorination. The importance of purified water is highlighted by the World Health Organization, who point out 94% of deaths from diarrhea – the third biggest cause of infectious death worldwide at 1.8 million annually – could be prevented by improving the quality of the victim's environment, particularly safe water.[16]

Pasteurisation

Pasteurisation is the process of heating a liquid for a period of time at a specified temperature, then immediately cooling. The process reduces the growth of microorganisms within the liquid, thereby increasing the time before spoilage. It is primarily used on milk, which prior to pasteurisation is commonly infected with pathogenic bacteria and therefore is more likely than any other part of the common diet in the developed world to cause illness.[17]

Juicing

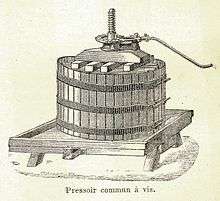

The process of extracting juice from fruits and vegetables can take a number of forms. Simple crushing of most fruits will provide a significant amount of liquid, though a more intense pressure can be applied to get the maximum amount of juice from the fruit. Both crushing and pressing are processes used in the production of wine.

Infusion

Infusion is the process of extracting flavours from plant material by allowing the material to remain suspended within water. This process is used in the production of teas, herbal teas and can be used to prepare coffee (when using a coffee press).

Percolation

The name is derived from the word "percolate" which means to cause (a solvent) to pass through a permeable substance especially for extracting a soluble constituent.[18] In the case of coffee-brewing the solvent is water, the permeable substance is the coffee grounds, and the soluble constituents are the chemical compounds that give coffee its color, taste, aroma, and stimulating properties.

Carbonation

Carbonation is the process of dissolving carbon dioxide into a liquid, such as water.

Fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that converts sugar to ethanol. Fermentation has been used by humans for the production of drinks since the Neolithic age. In winemaking, grape juice is combined with yeast in an anaerobic environment to allow the fermentation.[19] The amount of sugar in the wine and the length of time given for fermentation determine the alcohol level and the sweetness of the wine.[20]

When brewing beer, there are four primary ingredients – water, grain, yeast and hops. The grain is encouraged to germinate by soaking and drying in heat, a process known as malting. It is then milled before soaking again to create the sugars needed for fermentation. This process is known as mashing. Hops are added for flavouring, then the yeast is added to the mixture (now called wort) to start the fermentation process.[21]

Distillation

Distillation is a method of separating mixtures based on differences in volatility of components in a boiling liquid mixture. It is one of the methods used in the purification of water. It is also a method of producing spirits from milder alcoholic drinks.

Mixing

An alcoholic mixed drink that contains two or more ingredients is referred to as a cocktail. Cocktails were originally a mixture of spirits, sugar, water, and bitters.[22] The term is now often used for almost any mixed drink that contains alcohol, including mixers, mixed shots, etc.[23] A cocktail today usually contains one or more kinds of spirit and one or more mixers, such as soda or fruit juice. Additional ingredients may be sugar, honey, milk, cream, and various herbs.[24]

Type

Non-alcoholic drinks

A non-alcoholic drink is one that contains little or no alcohol. This category includes low-alcohol beer, non-alcoholic wine, and apple cider if they contain a sufficiently low concentration of alcohol by volume (ABV). The exact definition of what is "non-alcoholic" and what is not depends on local laws: in the United Kingdom, "alcohol-free beer" is under 0.05% ABV, "de-alcoholised beer" is under 0.5%, while "low-alcohol beer" can contain no more than 1.2% ABV.[25] The term "soft drink" specifies the absence of alcohol in contrast to "hard drink" and "drink". The term "drink" is theoretically neutral, but often is used in a way that suggests alcoholic content. Drinks such as soda pop, sparkling water, iced tea, lemonade, root beer, fruit punch, milk, hot chocolate, tea, coffee, milkshakes, and tap water and energy drinks are all soft drinks.

Water

Water is the world's most consumed drink,[26] however, 97% of water on Earth is non-drinkable salt water.[27] Fresh water is found in rivers, lakes, wetlands, groundwater, and frozen glaciers.[28] Less than 1% of the Earth's fresh water supplies are accessible through surface water and underground sources which are cost effective to retrieve.[29]

In western cultures, water is often drunk cold. In the Chinese culture, it is typically drunk hot.[30]

Milk

Regarded as one of the "original" drinks,[31] milk is the primary source of nutrition for babies. In many cultures of the world, especially the Western world, humans continue to consume dairy milk beyond infancy, using the milk of other animals (especially cattle, goats and sheep) as a drink. Plant milk, a general term for any milk-like product that is derived from a plant source, also has a long history of consumption in various countries and cultures. The most popular varieties internationally are soy milk, almond milk, rice milk and coconut milk.

Soft drinks

Carbonated drinks refer to drinks which have carbon dioxide dissolved into them. This can happen naturally through fermenting and in natural water spas or artificially by the dissolution of carbon dioxide under pressure. The first commercially available artificially carbonated drink is believed to have been produced by Thomas Henry in the late 1770s.[32] Cola, orange, various roots, ginger, and lemon/lime are commonly used to create non-alcoholic carbonated drinks; sugars and preservatives may be added later.[33]

The most consumed carbonated soft drinks are produced by three major global brands: Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and the Dr Pepper Snapple Group.[34]

Juice and juice drinks

Fruit juice is a natural product that contains few or no additives. Citrus products such as orange juice and tangerine juice are familiar breakfast drinks, while grapefruit juice, pineapple, apple, grape, lime, and lemon juice are also common. Coconut water is a highly nutritious and refreshing juice. Many kinds of berries are crushed; their juices are mixed with water and sometimes sweetened. Raspberry, blackberry and currants are popular juices drinks but the percentage of water also determines their nutritive value. Grape juice allowed to ferment produces wine.

Fruits are highly perishable so the ability to extract juices and store them was of significant value. Some fruits are highly acidic and mixing them with water and sugars or honey was often necessary to make them palatable. Early storage of fruit juices was labor-intensive, requiring the crushing of the fruits and the mixing of the resulting pure juices with sugars before bottling.

Vegetable juices are usually served warm or cold. Different types of vegetables can be used to make vegetable juice such as carrots, tomatoes, cucumbers, celery and many more. Some vegetable juices are mixed with some fruit juice to make the vegetable juice taste better. Many popular vegetable juices, particularly ones with high tomato content, are high in sodium, and therefore consumption of them for health must be carefully considered. Some vegetable juices provide the same health benefits as whole vegetables in terms of reducing risks of cardiovascular disease and cancer.

| Type of fruit drink | Percentage of fruit needed in drink | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Fruit juice[35] | 100%[36] | Largely regulated throughout the world; 'juice' is often protected to be used for only 100% fruit.[36] |

| Fruit drink[35] | 10%[33][35] | Fruit is liquefied and water added.[35] |

| Fruit squash[35] | 25%[35] | Produced using strained fruit juice, 45% sugar and preservatives.[35] |

| Fruit cordial[35] | 0%[37] | All 'suspended matter' is eliminated by filtration or clarification.[35] and therefore appears clear[33] This type of drink, if described as 'flavoured,' may not have any amount of fruit.[37] |

| Fruit punch[35] | 25%[35] | A mixture of fruit juices. Contains around 65% sugar.[35] |

| Fruit syrups[35] | - | 1 fruit crushed into puree and left to ferment. Is then heated with sugar to create syrup.[33][35] |

| Fruit juice concentrates[35] | 100%[35] | Water removed from fruit juice by heating or freezing.[33] |

| Carbonated fruit drinks[35] | - | Carbon dioxide added to fruit drink.[35] |

| Fruit nectars[38] | 30%[38] | Mixture of fruit pulp, sugar and water which is consumed as 'one shot'.[38] |

| Fruit Sherbets[39] | - | Cooled drink of sweetened diluted fruit juice.[39] |

Sleep drinks

A nightcap is a drink taken shortly before bedtime to induce sleep. For example, a small alcoholic drink or a cup of warm milk can supposedly promote a good night's sleep. Today, most nightcaps and relaxation drinks are generally non-alcoholic beverages containing calming ingredients. They are considered beverages which serve to relax a person. Unlike other calming beverages, such as tea, warm milk or milk with honey; relaxation drinks almost universally contain more than one active ingredient. Relaxation drinks have been known to contain other natural ingredients and are usually free of caffeine and alcohol but some have claimed to contain marijuana.

Alcoholic drinks

A drink is considered "alcoholic" if it contains ethanol, commonly known as alcohol (although in chemistry the definition of "alcohol" includes many other compounds). Beer has been a part of human culture for 8,000 years.[40]

In many countries, imbibing alcoholic drinks in a local bar or pub is a cultural tradition.[41]

Beer

Beer is an alcoholic drink produced by the saccharification of starch and fermentation of the resulting sugar. The starch and saccharification enzymes are often derived from malted cereal grains, most commonly malted barley and malted wheat.[42] Most beer is also flavoured with hops, which add bitterness and act as a natural preservative, though other flavourings such as herbs or fruit may occasionally be included. The preparation of beer is called brewing. Beer is the world's most widely consumed alcoholic drink,[43] and is the third-most popular drink overall, after water and tea. It is said to have been discovered by goddess Ninkasi around 5300 BCE, when she accidentally discovered yeast after leaving grain in jars that were later rained upon and left for several days. Women have been the chief creators of beer throughout history due to its association with domesticity and it, throughout much of history, being brewed in the home for family consumption. Only in recent history have men began to dabble in the field.[44][45] It is thought by some to be the oldest fermented drink.[46][47][48][49]

Some of humanity's earliest known writings refer to the production and distribution of beer: the Code of Hammurabi included laws regulating beer and beer parlours,[50] and "The Hymn to Ninkasi", a prayer to the Mesopotamian goddess of beer, served as both a prayer and as a method of remembering the recipe for beer in a culture with few literate people.[51][52] Today, the brewing industry is a global business, consisting of several dominant multinational companies and many thousands of smaller producers ranging from brewpubs to regional breweries.

Cider

Cider is a fermented alcoholic drink made from fruit juice, most commonly and traditionally apple juice, but also the juice of peaches, pears ("Perry" cider) or other fruit. Cider may be made from any variety of apple, but certain cultivars grown solely for use in cider are known as cider apples.[53] The United Kingdom has the highest per capita consumption of cider, as well as the largest cider-producing companies in the world,[54] As of 2006, the U.K. produces 600 million litres of cider each year (130 million imperial gallons).[55]

Wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink made from fermented grapes or other fruits. The natural chemical balance of grapes lets them ferment without the addition of sugars, acids, enzymes, water, or other nutrients.[56] Yeast consumes the sugars in the grapes and converts them into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts produce different styles of wine. The well-known variations result from the very complex interactions between the biochemical development of the fruit, reactions involved in fermentation, terroir and subsequent appellation, along with human intervention in the overall process. The final product may contain tens of thousands of chemical compounds in amounts varying from a few percent to a few parts per billion.

Wines made from produce besides grapes are usually named after the product from which they are produced (for example, rice wine, pomegranate wine, apple wine and elderberry wine) and are generically called fruit wine. The term "wine" can also refer to starch-fermented or fortified drinks having higher alcohol content, such as barley wine, huangjiu, or sake.

Wine has a rich history dating back thousands of years, with the earliest production so far discovered having occurred c. 6000 BC in Georgia.[4][57][5] It had reached the Balkans by c. 4500 BC and was consumed and celebrated in ancient Greece and Rome.

From its earliest appearance in written records, wine has also played an important role in religion. Red wine was closely associated with blood by the ancient Egyptians, who, according to Plutarch, avoided its free consumption as late as the 7th-century BC Saite dynasty, "thinking it to be the blood of those who had once battled against the gods".[58] The Greek cult and mysteries of Dionysus, carried on by the Romans in their Bacchanalia, were the origins of western theater. Judaism incorporates it in the Kiddush and Christianity in its Eucharist, while alcohol consumption was forbidden in Islam.

Spirits

Spirits are distilled beverages that contain no added sugar and have at least 20% alcohol by volume (ABV). Popular spirits include borovička, brandy, gin, rum, slivovitz, tequila, vodka, and whisky. Brandy is a spirit created by distilling wine, whilst vodka may be distilled from any starch- or sugar-rich plant matter; most vodka today is produced from grains such as sorghum, corn, rye or wheat.

Hot drinks

Coffee

Coffee is a brewed drink prepared from the roasted seeds of several species of an evergreen shrub of the genus Coffea. The two most common sources of coffee beans are the highly regarded Coffea arabica, and the "robusta" form of the hardier Coffea canephora. Coffee plants are cultivated in more than 70 countries. Once ripe, coffee "berries" are picked, processed, and dried to yield the seeds inside. The seeds are then roasted to varying degrees, depending on the desired flavor, before being ground and brewed to create coffee.

Coffee is slightly acidic (pH 5.0–5.1[59]) and can have a stimulating effect on humans because of its caffeine content. It is one of the most popular drinks in the world.[60] It can be prepared and presented in a variety of ways. The effect of coffee on human health has been a subject of many studies; however, results have varied in terms of coffee's relative benefit.[61]

Coffee cultivation first took place in southern Arabia;[62] the earliest credible evidence of coffee-drinking appears in the middle of the 15th century in the Sufi shrines of Yemen.[62]

Hot chocolate

Hot chocolate, also known as drinking chocolate or cocoa, is a heated drink consisting of shaved chocolate, melted chocolate or cocoa powder, heated milk or water, and usually a sweetener. Hot chocolate may be topped with whipped cream. Hot chocolate made with melted chocolate is sometimes called drinking chocolate, characterized by less sweetness and a thicker consistency.[63]

The first chocolate drink is believed to have been created by the Mayans around 2,500-3,000 years ago, and a cocoa drink was an essential part of Aztec culture by 1400 AD, by which they referred to as xocōlātl.[64][65] The drink became popular in Europe after being introduced from Mexico in the New World and has undergone multiple changes since then. Until the 19th century, hot chocolate was even used medicinally to treat ailments such as liver and stomach diseases.

Hot chocolate is consumed throughout the world and comes in multiple variations, including the spiced chocolate para mesa of Latin America, the very thick cioccolata calda served in Italy and chocolate a la taza served in Spain, and the thinner hot cocoa consumed in the United States. Prepared hot chocolate can be purchased from a range of establishments, including cafeterias, fast food restaurants, coffeehouses and teahouses. Powdered hot chocolate mixes, which can be added to boiling water or hot milk to make the drink at home, are sold at grocery stores and online.

Tea

Tea, the second most consumed drink in the world, is produced from infusing dried leaves of the camellia sinensis shrub, in boiling water.[66] There are many ways in which tea is prepared for consumption: lemon or milk and sugar are among the most common additives worldwide. Other additions include butter and salt in Bhutan, Nepal, and Tibet; bubble tea in Taiwan; fresh ginger in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore; mint in North Africa and Senegal; cardamom in Central Asia; rum to make Jagertee in Central Europe; and coffee to make yuanyang in Hong Kong. Tea is also served differently from country to country: in China and Japan tiny cups are used to serve tea; in Thailand and the United States tea is often served cold (as "iced tea") or with a lot of sweetener; Indians boil tea with milk and a blend of spices as masala chai; tea is brewed with a samovar in Iran, Kashmir, Russia and Turkey; and in the Australian Outback it is traditionally brewed in a billycan.[67] Tea leaves can be processed in different ways resulting in a drink which appears and tastes different. Chinese yellow and green tea are steamed, roasted and dried; Oolong tea is semi-oxidised and appears green-black and black teas are fully oxidised.[68]

Around the world, people refer to other herbal infusions as "teas"; it is also argued that these were popular long before the Camellia sinensis shrub was used for tea making.[69] Leaves, flowers, roots or bark can be used to make a herbal infusion and can be bought fresh, dried or powdered.[70]

In culture

Places to drink

.jpg)

Throughout history, people have come together in establishments to socialise whilst drinking. This includes cafés and coffeehouses, focus on providing hot drinks as well as light snacks. Many coffee houses in the Middle East, and in West Asian immigrant districts in the Western world, offer shisha (nargile in Turkish and Greek), flavored tobacco smoked through a hookah. Espresso bars are a type of coffeehouse that specialize in serving espresso and espresso-based drinks.

In China and Japan, the establishment would be a tea house, were people would socialise whilst drinking tea. Chinese scholars have used the teahouse for places of sharing ideas.

Alcoholic drinks are served in drinking establishments, which have different cultural connotations. For example, pubs are fundamental to the culture of Britain,[71][72] Ireland,[73] Australia,[74] Canada, New England, Metro Detroit, South Africa and New Zealand. In many places, especially in villages, a pub can be the focal point of the community. The writings of Samuel Pepys describe the pub as the heart of England. Many pubs are controlled by breweries, so cask ale or keg beer may be a better value than wines and spirits.

In contrast, types of bars range from seedy bars or nightclubs, sometimes termed "dive bars",[75] to elegant places of entertainment for the elite. Bars provide stools or chairs that are placed at tables or counters for their patrons. The term "bar" is derived from the specialized counter on which drinks are served. Some bars have entertainment on a stage, such as a live band, comedians, go-go dancers, or strippers. Patrons may sit or stand at the bar and be served by the bartender, or they may sit at tables and be served by cocktail servers.

Matching with food

Food and drink are often paired together to enhance the taste experience. This primarily happens with wine and a culture has grown up around the process. Weight, flavors and textures can either be contrasted or complemented.[76] In recent years, food magazines began to suggest particular wines with recipes and restaurants would offer multi-course dinners matched with a specific wine for each course.[77]

Presentation

Different drinks have unique receptacles for their consumption. This is sometimes purely for presentations purposes, such as for cocktails. In other situations, the drinkware has practical application, such as coffee cups which are designed for insulation or brandy snifters which are designed to encourage evaporation but trap the aroma within the glass.

Many glasses include a stem, which allows the drinker to hold the glass without affecting the temperature of the drink. In champagne glasses, the bowl is designed to retain champagne's signature carbonation, by reducing the surface area at the opening of the bowl. Historically, champagne has been served in a champagne coupe, the shape of which allowed carbonation to dissipate even more rapidly than from a standard wine glass.

Commercial trade

International exports and imports

An important export commodity, coffee was the top agricultural export for twelve countries in 2004,[78] and it was the world's seventh-largest legal agricultural export by value in 2005.[79] Green (unroasted) coffee is one of the most traded agricultural commodities in the world.[80]

Investment

Some drinks, such as wine, can be used as an alternative investment.[81] This can be achieved by either purchasing and reselling individual bottles or cases of particular wines, or purchasing shares in an investment wine fund that pools investors' capital.[82]

See also

- List of beverages

- List of hot drinks

- List of national drinks

References

- Cheney, Ralph (July 1947). "The Biology and Economics of the Beverage Industry". Economic Botany. 1 (3): 243–275. doi:10.1007/bf02858570. JSTOR 4251857.

- Burnett, John (2012). Liquid Pleasures: A Social History of Drinks in Modern Britain. Routledge. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-1-134-78879-8.

- Keys, David (2003-12-28). "Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine". The Independent. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- Berkowitz, Mark (1996). "World's Earliest Wine". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 49 (5). Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- Spilling, Michael; Wong, Winnie (2008). Cultures of The World Georgia. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7614-3033-9.

- Ellsworth, Amy (18 July 2012). "7,000 Year-old Wine Jar".

- Prehistoric brewing: the true story, 22 October 2001, Archaeo News. Retrieved 13 September 2008

- "Dreher Breweries, Beer-history". Archived from the original on 2009-07-09. Retrieved 2010-09-21.

- Mirsky, Steve (May 2007). "Ale's Well with the World". Scientific American. 296 (5): 102. Bibcode:2007SciAm.296e.102M. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0507-102. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- Dornbusch, Horst (27 August 2006). "Beer: The Midwife of Civilization". Assyrian International News Agency. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- Protz, Roger (2004). "The Complete Guide to World Beer".

When people of the ancient world realised they could make bread and beer from grain, they stopped roaming and settled down to cultivate cereals in recognisable communities.

- Mary Lou Heiss; Robert J. Heiss. The Story of Tea: A Cultural History and Drinking Guide.

- Katsigris, Costas; Thomas, Chris (2006). The Bar and Beverage Book. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 5–10. ISBN 978-0-470-07344-5.

- Pankhurst, Richard (1968). Economic History of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Haile Selassie I University. p. 198.

- Hopkins, Kate (March 24, 2006). "Food Stories: The Sultan's Coffee Prohibition". Accidental Hedonist. Archived from the original on November 20, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- Combating Waterborne Diseases at the Household Level (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. p. 11. ISBN 978-92-4-159522-3.

- Wilson, G. S. (1943), "The Pasteurization of Milk", British Medical Journal, 1 (4286): 261–262, doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4286.261, PMC 2282302, PMID 20784713

- "percolate". Merriam Webster. 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- Jeff Cox "From Vines to Wines: The Complete Guide to Growing Grapes and Making Your Own Wine" pgs 133–136 Storey Publishing 1999 ISBN 1-58017-105-2

- D. Bird "Understanding Wine Technology" pg 67–73 DBQA Publishing 2005 ISBN 1-891267-91-4

- Matthew Schaefer (15 Feb 2012). The Illustrated Guide to Brewing Beer. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-61608-463-9. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Thomas, Jerry (1862). How To Mix Drinks.

- Regan, Gary (2003). The Joy of Mixology. Potter.

- DeGroff, Dale (2002). The Craft of the Cocktail. Potter.

- "Differences between alcoholic and non-alcoholic beers". www.drinkaware.co.uk. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Griffiths, John (2007). Tea: The Drink That Changed the World. Andre Deutsch. ISBN 978-0-233-00212-5.

- "Earth's water distribution". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- Where is Earth's water? Archived 2013-12-14 at the Wayback Machine, United States Geological Survey.

- Van Ginkel, J. A. (2002). Human Development and the Environment: Challenges for the United Nations in the New Millennium. United Nations University Press. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-9280810691.

- Liu, Nicole (12 March 2016). "China's go-to beverage? Hot water. Really". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- Richards, Edgar (5 September 1890). "Beverages". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 16 (396): 127–131. Bibcode:1890Sci....16..127R. doi:10.1126/science.ns-16.396.127. JSTOR 1766104. PMID 17782638.

- Steen, Dr. David; Ashhurst, Philip. (2008). Carbonated Soft Drinks: Formulation and Manufacture. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-4051-7170-0.

- Sivasankar, B. (2002). "24". FOOD PROCESSING AND PRESERVATION. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 314. ISBN 978-8120320864.

- "Soft Drink Industry: Market Research Reports, Statistics and Analysis". Report Linker. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- Srilakshmi, B. (2003). Food Science (3rd ed.). New Age International. p. 269. ISBN 978-8122414813.

- Ashurst, Philip R. (1994). Production and Packaging of Non-Carbonated Fruit Juices and Fruit Beverages (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 360–362. ISBN 978-0-8342-1289-3.

- Cooper, Derek (1970). The Beverage Report. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. p. 55.

- Chandrasekaran, M. (2012). Valorization of Food Processing By-Products. Fermented foods and drinks series. CRC Press. p. 595. ISBN 978-1-4398-4885-2.

- Desai (2000). Handbook of Nutrition and Diet. Food Science and Technology. CRC Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-4200-0161-7.

- Arnold, John P (2005). Origin and History of Beer and Brewing: From Prehistoric Times to the Beginning of Brewing Science and Technology (Reprint ed.). BeerBooks.com.

- Hamill, Pete (1994). A Drinking Life: A Memoir. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-34102-8.

- Barth, Roger. The Chemistry of Beer: The Science in the Suds, Wiley 2013: ISBN 978-1-118-67497-0.

- "Volume of World Beer Production". European Beer Guide. Archived from the original on 28 October 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- Shoemaker, Camille (May 2017), Women & the Beverage that Changed the World., National Women's History Museum

- Nelson, Max (2005). The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-415-31121-2. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- Rudgley, Richard (1993). The Alchemy of Culture: Intoxicants in Society. London: British Museum Press. p. 411. ISBN 978-0-7141-1736-2. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- Arnold, John P (2005). Origin and History of Beer and Brewing: From Prehistoric Times to the Beginning of Brewing Science and Technology. Cleveland, Ohio: Reprint Edition by BeerBooks. p. 411. ISBN 978-0-9662084-1-2. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- Joshua J. Mark (2011). Beer. Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- World's Best Beers: One ThousandCraft Brews from Cask to Glass. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. 6 October 2009. ISBN 978-1-4027-6694-7. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- "Beer Before Bread". Alaska Science Forum #1039, Carla Helfferich. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- "Nin-kasi: Mesopotamian Goddess of Beer". Matrifocus 2006, Johanna Stuckey. Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- Black, Jeremy A.; Cunningham, Graham; Robson, Eleanor (2004). The literature of ancient Sumer. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926311-0.

- Lea, Andrew. "The Science of Cidermaking Part 1 – Introduction". Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- "National Association of Cider Makers". Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- "Interesting Facts". National Association of Cider Makers. Archived from the original on 14 February 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- Johnson, H. (1989). Vintage: The Story of Wine. Simon & Schuster. pp. 11–6. ISBN 978-0-671-79182-7.

- Keys, David (28 December 2003). "Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine". The Independent. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "Isis & Osiris". Nature. University of Chicago. 146 (3695): 262–263. 1940. Bibcode:1940Natur.146U.262.. doi:10.1038/146262e0.

- Coffee and Health. Thecoffeefaq.com (2005-02-16). Retrieved on 2013-01-22.

- Villanueva, Cristina M.; Cantor, Kenneth P.; King, Will D.; Jaakkola, Jouni J.K.; Cordier, Sylvaine; Lynch, Charles F.; Porru, Stefano; Kogevinas, Manolis (2006). "Total and specific fluid consumption as determinants of bladder cancer risk". International Journal of Cancer. 118 (8): 2040–7. doi:10.1002/ijc.21587. PMID 16284957.

- Kummer 2003, pp. 160–5

- Weinberg, Bennett Alan; Bealer, Bonnie K. (2001). The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug. New York: Routledge. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-415-92722-2. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- Grivetti, Louis E.; Shapiro, Howard-Yana (2009). Chocolate: history, culture, and heritage. John Wiley and Sons. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-470-12165-8.

- Bee Wilson (15 Sep 2009). "Aztecs and cacao: the bittersweet past of chocolate". Telegraph.

- Trivedi, Bijal (July 17, 2012). "Ancient Chocolate Found in Maya "Teapot"". National Geographic. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- Martin, Laura C. (2007). Tea: The Drink that Changed the World. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-8048-3724-8.

- Saberi, Helen (2010). Tea: A Global History. Reaktion Books. pp. 7. ISBN 978-1-86189-892-0.

- Gibson, E.L.; Rycroft, J.A. (2011). "41". In Victor R. Preedy (ed.). Psychological and Physiological Consequences of Drinking Tea in Handbook of Behavior, Food and Nutrition. Watson, R.; Martin, C. Springer. pp. 621–623. ISBN 978-0-387-92271-3.

- Mars, Brigitte (2009). Healing Herbal Teas: A Complete Guide to Making Delicious, Healthful Beverages. ReadHowYouWant.com. pp. vi. ISBN 978-1-4429-6955-1.

- Safi, Tammy (2001). Healthy Teas: Green, Black, Herbal, Fruit (Illustrated ed.). Tuttle Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7946-5004-9.

- Public House Britannica.com; Subscription Required. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- "Scottish pubs". Insiders-scotland-guide.com. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- Cronin, Michael; O'Connor, Barbara (2003). Barbara O'Connor (ed.). Irish Tourism: image, culture, and identity. Tourism and Cultural Change. 1. Channel View Publications. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-873150-53-5. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- Australian Drinking Culture Convict Creations. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- Todd Dayton, San Francisco's Best Dive Bars, page 4. Ig Publishing. 2009. ISBN 978-0-9703125-8-7. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- M. Oldman "Oldman's Guide to Outsmarting Wine" pg 219-235 Penguin Books 2004 ISBN 0-14-200492-8

- K. MacNeil The Wine Bible pg 83-88 Workman Publishing 2001 ISBN 1-56305-434-5

- "FAO Statistical Yearbook 2004 Vol. 1/1 Table C.10: Most important imports and exports of agricultural products (in value terms) (2004)" (PDF). FAO Statistics Division. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-25. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- "FAOSTAT Core Trade Data (commodities/years)". FAO Statistics Division. 2007. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved October 24, 2007. To retrieve export values: Select the "commodities/years" tab. Under "subject", select "Export value of primary commodity." Under "country," select "World." Under "commodity," hold down the shift key while selecting all commodities under the "single commodity" category. Select the desired year and click "show data." A list of all commodities and their export values will be displayed.

- Mussatto, Solange I.; Machado, Ercília M. S.; Martins, Silvia; Teixeira, José A. (2011). "Production, Composition, and Application of Coffee and Its Industrial Residues" (PDF). Food and Bioprocess Technology. 4 (5): 661–72. doi:10.1007/s11947-011-0565-z. hdl:1822/22361.

- Greenwood, By John (2008-10-06). "First class returns for alternative investments".

- "Buying wine for investment". IFWIC.org. Archived from the original on 16 January 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

Bibliography

- Kummer, Corby (August 19, 2003). The Joy of Coffee: The Essential guide to Buying, Brewing, and Enjoying. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-30240-6.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Drink |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Drink. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Beverages. |

- Hana LaRock (30 Aug 2019). "8 of the world's most unusual drinks". CNN.

- Health-EU Portal – Alcohol

- Wikibooks Cookbook

- Women and Beer: A Forgotten Pairing (National Women's History Museum)