Enclosure

Enclosure (sometimes inclosure) was the legal process in England of consolidating (enclosing) small landholdings into larger farms[1] since the 13th century. Once enclosed, use of the land became restricted and available only to the owner, and it ceased to be common land for communal use. In England and Wales the term is also used for the process that ended the ancient system of arable farming in open fields. Under enclosure, such land is fenced (enclosed) and deeded or entitled to one or more owners. The process of enclosure began to be a widespread feature of the English agricultural landscape during the 16th century. By the 19th century, unenclosed commons had become largely restricted to rough pasture in mountainous areas and to relatively small parts of the lowlands.

Enclosure could be accomplished by buying the ground rights and all common rights to accomplish exclusive rights of use, which increased the value of the land. The other method was by passing laws causing or forcing enclosure, such as Parliamentary enclosure involving an Inclosure Act. The latter process of enclosure was sometimes accompanied by force, resistance, and bloodshed, and remains among the most controversial areas of agricultural and economic history in England. Marxist historians argue that rich landowners used their control of state processes to appropriate public land for their private benefit.[2] During the Georgian era, the process of enclosure created a landless working class that provided the labour required in the new industries developing in the north of England. For example: "In agriculture the years between 1760 and 1820 are the years of wholesale enclosure in which, in village after village, common rights are lost."[3] E. P. Thompson argues that "Enclosure (when all the sophistications are allowed for) was a plain enough case of class robbery."[4][5]

W. A. Armstrong, among others, argued that this is perhaps an oversimplification, that the better-off members of the European peasantry encouraged and participated actively in enclosure, seeking to end the perpetual poverty of subsistence farming. "We should be careful not to ascribe to [enclosure] developments that were the consequence of a much broader and more complex process of historical change."[6] Armstrong notes that enclosure had varying impacts on levels of poor relief in western and eastern counties, and suggests the decrease in agricultural wages in this period (and subsequent emigration to urban areas) was more related to overall rural population growth instead.[7][8]

Enclosure is considered one of the causes of the British Agricultural Revolution. Enclosed land was under control of the farmer who was free to adopt better farming practices. There was widespread agreement in contemporary accounts that profit making opportunities were better with enclosed land.[9] Following enclosure, crop yields increased while at the same time labour productivity increased enough to create a surplus of labour. The increased labour supply is considered one of the causes of the Industrial Revolution.[10] Karl Marx argued in Capital that enclosure played a constitutive role in the revolutionary transformation of feudalism into capitalism, both by transforming land from a means of subsistence into a means to realize profit on commodity markets (primarily wool in the English case), and by creating the conditions for the modern labour market by unifying smallholders and pastoralists into the mass of agricultural wage-labourers, i.e. those whose opportunities to exit the market declined as the common lands were enclosed.[11]

Early history

Enclosure of manorial common land was authorised by the Statute of Merton (1235) and the Statute of Westminster (1285).

Throughout the medieval and modern periods, piecemeal enclosure took place in which adjacent strips were fenced off from the common field. This was sometimes undertaken by small landowners, but more often by large landowners and lords of the manor. Significant enclosures (or emparkments) took place to establish deer parks. Some (but not all) of these enclosures took place with local agreement.[12] Most if not all emparkments were of already fenced land. Often large land was owned by the major landowners and lords.

Tudor enclosures

From as early as the 12th century, some open fields in Britain were being enclosed into individually owned fields. However there was a significant rise in enclosure during the Tudor period. These enclosures largely resulted in conversion of land use from arable to pasture – usually sheep farming. These enclosures were often undertaken unilaterally by the landowner. Enclosures during the Tudor period were often accompanied by a loss of common rights and could result in the destruction of whole villages.[13]

English champaign (extensive, open land) had been commonly enclosed as pastureland for sheep from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century as populations declined. Foreign demand for English wool also helped encourage increased production, and the wool industry was often thought to be more profitable for landowners who had large decaying farmlands. Some manorial lands lay in disrepair from a lack of tenants, which made them undesirable to both prospective tenants and landowners who could be fined and ordered to make repairs. Enclosure and sheep herding (which required very few labourers) were a solution to the problem, but resulted in unemployment, the displacement of impoverished rural labourers, and decreased domestic grain production which made England more susceptible to famine and higher prices for domestic and foreign grain. In Great Britain, the process sped up during the 15th and 16th centuries as sheep farming grew more profitable. In the 16th and early 17th centuries, the practice of enclosure, particularly of depopulating enclosure, was denounced by the Church and the government and legislation was drawn up against it. But elite opinion began to turn towards support for enclosure, and rate of enclosure increased in the seventeenth century. This led to a series of government acts addressing individual regions, which were given a common framework in the Inclosure Consolidation Act of 1801.

Sir Thomas More, in his 1516 work Utopia suggests that the practice of enclosure was responsible for some of the social problems affecting England at the time, specifically theft:

"But I do not think that this necessity of stealing arises only from hence; there is another cause of it, more peculiar to England." "What is that?" said the Cardinal. "The increase of pasture," said I, "by which your sheep, which are naturally mild, and easily kept in order, may be said now to devour men and unpeople, not only villages, but towns; for wherever it is found that the sheep of any soil yield a softer and richer wool than ordinary, there the nobility and gentry, and even those holy men, the abbots not contented with the old rents which their farms yielded, nor thinking it enough that they, living at their ease, do no good to the public, resolve to do it hurt instead of good. They stop the course of agriculture, destroying houses and towns – reserving only the churches – and enclose grounds that they may lodge their sheep in them."[14]

The loss of agricultural labour also hurt others like millers whose livelihood relied on agricultural produce. Fynes Moryson reported on these problems in his 1617 work An Itinerary:[15]

England abounds with corn [wheat and other grains], which they may transport, when a quarter (in some places containing six, in others eight bushels) is sold for twenty shillings, or under; and this corn not only serves England, but also served the English army in the civil wars of Ireland, at which time they also exported great quantity thereof into foreign parts, and by God's mercy England scarce once in ten years needs a supply of foreign corn, which want commonly proceeds of the covetousness of private men, exporting or hiding it. Yet I must confess, that daily this plenty of corn decreaseth, by reason that private men, finding greater commodity in feeding of sheep and cattle than in the plow, requiring the hands of many servants, can by no law be restrained from turning cornfields into enclosed pastures, especially since great men are the first to break these laws.

Anti-enclosure legislation

Manorial lords' enclosure of common land (particularly to monopolise local sheep farming) and the consequent eviction of commoners or villagers from their homes and their livelihoods became an important political issue for the Tudors. Enclosure led to homeless, displaced inhabitants, potential underclass rebels. The King's advisers were extremely nervous about such impoverishment or "beggaring". Commoners kept informal homes and farms, a broad stream of non-collectivised tax revenues. Workers were strong-limbed, frequent military conscripts for the crown. In the sixteenth century, lack of income made one a pauper. If one lost one's home as well, one became a vagrant; and vagrants were regarded (and treated) as criminals. The authorities saw many people becoming what they regarded as vagabonds and thieves as a result of enclosure and depopulation of villages.

Reflecting these factors, the anti-enclosure acts of 1489 began those aimed to stem enclosure. From the time of Henry VII, Parliament began passing Acts to stop enclosure, to limit its effects, or at least to fine those responsible. Over the next 150 years, there were 11 more Acts of Parliament and eight commissions of enquiry on the subject.[16]

Initially, enclosure was not itself an offence, but where it was accompanied by the destruction of houses, half the (land's annual) profits would go to the Crown until the lost houses were rebuilt (the 1489 Act gave half these net revenues to the superior landlord, who might not be the Crown, but an Act of 1536 allowed the Crown to receive this half share if the superior landlord had not taken action to claim it). In 1515, conversion from arable to pasture became an offence. Once again, half the profits from conversion would go to the Crown until the arable land was restored. Neither the 1515 Act nor the previous laws were watertight in stopping enclosure, so in 1517 Cardinal Wolsey established a commission of enquiry to determine where offences had taken place – and to ensure the Crown received its punitive half-share of annual agricultural profits.

Inflation and enclosure

Alongside population growth,[17] inflation was a major reason for enclosure.[18] When Henry VIII became King in 1509, he found the royal finances in good shape thanks to the prudence of his father Henry VII (reigned 1485–1509). But this soon changed as Henry VIII doubled household expenditure and started costly wars against both France and Scotland. With his wealth rapidly decreasing, Henry VIII imposed a series of taxes devised by his Chancellor, Thomas Wolsey (in office 1515–1529). Soon the people began to resent Wolsey's taxes and the administration had to find a new source of finance: in 1544, Henry reduced the silver content of new coins by about 50%; he repeated the process to a lesser extent the following year. This, combined with injection of bullion from the New World, increased the money supply in England, which led to continuing price inflation.

The debasement of the coinage was not seen as a cause of inflation (and therefore of enclosures) until the Duke of Somerset became Lord Protector (1547–1549) during the reign of Edward VI (1547–1553). Until then enclosures were seen as the cause of inflation, not the outcome. When Thomas Smith advised Somerset that enclosure resulted from inflation, Somerset ignored him. It was not until John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland became de facto ruler that his Secretary of State William Cecil (in office 1550–1553) took action on debasement to try to stop enclosure.

Enclosure riots

After 1529 or so, the problem of untended farmland disappeared with the rising population. There was a desire for more arable land along with much antagonism toward the tenant-graziers with their flocks and herds. Increased demand along with a scarcity of tillable land caused rents to rise dramatically in the 1520s to mid-century. The 1520s appear to have been the point at which the rent increases became extreme, with complaints of rack-rent appearing in popular literature, such as the works of Robert Crowley. There were popular efforts to remove old enclosures, and much legislation of the 1530s and 1540s concerns this shift. Angry tenants impatient to reclaim pastures for tillage were illegally destroying enclosures. Beginning with Kett's Rebellion in 1549, agrarian revolts swept all over the nation, and other revolts occurred periodically throughout the century. The popular rural mentality was to restore the security, stability, and functionality of the old commons system. Historians would write that they were asserting ancient traditional and constitutional rights granted to the free and sturdy English yeoman as opposed to the enslaved and effeminate French. This emphasis on rights was to have a pivotal role in the modern era unfolding from the Enlightenment. D. C. Coleman writes that the English commons were disturbed by the loss of common rights under enclosure which might involve the right "to cut underwood, to run pigs".

Midland Revolt

In 1607, beginning on May Eve in Haselbech, Northamptonshire and spreading to Warwickshire and Leicestershire throughout May, riots took place as a protest against the enclosure of common land. Now known as the Midland Revolt, it drew considerable support and was led by John Reynolds, otherwise known as 'Captain Pouch', a tinker said to be from Desborough, Northamptonshire. He told the protesters he had authority from the King and the Lord of Heaven to destroy enclosures and promised to protect protesters by the contents of his pouch, carried by his side, which he said would keep them from all harm (after he was captured, his pouch was opened; all that was in it was a piece of green cheese). Thousands of people were recorded at Hillmorton, Warwickshire and at Cotesbach, Leicestershire. A curfew was imposed in the city of Leicester, as it was feared citizens would stream out of the city to join the riots. A gibbet was erected in Leicester as a warning, and was pulled down by the citizens.

Newton Rebellion: 8 June 1607

The Newton Rebellion was one of the last times that the non-mining commoners of England and the gentry were in open, armed conflict.[19] Things had come to a head in early June. James I issued a Proclamation and ordered his Deputy Lieutenants in Northamptonshire to put down the riots. It is recorded that women and children were part of the protest. Over a thousand had gathered at Newton, near Kettering, pulling down hedges and filling ditches, to protest against the enclosures of Thomas Tresham.[19]

The Treshams were unpopular for their voracious enclosing of land – the family at Newton and their better-known Roman Catholic cousins at nearby Rushton, the family of Francis Tresham, who had been involved two years earlier in the Gunpowder Plot and had by announcement died in London's Tower. Sir Thomas Tresham of Rushton was vilified as 'the most odious man' in Northamptonshire. The old Roman Catholic gentry family of the Treshams had long argued with the emerging Puritan gentry family, the Montagus of Boughton, about territory. Now Tresham of Newton was enclosing common land – The Brand – that had been part of Rockingham Forest.[19]

Edward Montagu, one of the Deputy Lieutenants, had stood up against enclosure in Parliament some years earlier, but was now placed by the King in the position effectively of defending the Treshams. The local armed bands and militia refused the call-up, so the landowners were forced to use their own servants to suppress the rioters on 8 June 1607. The Royal Proclamation of King James was read twice. The rioters continued in their actions, although at the second reading some ran away. The gentry and their forces charged. A pitched battle ensued in which 40–50 people were killed; the ringleaders were hanged and quartered. A much-later memorial stone to those killed stands at the former church of St Faith, Newton.[19]

The Tresham family declined soon after 1607. The Montagu family went on through marriage to become the Dukes of Buccleuch, enlarging the wealth of the senior branch substantially.[19]

Western Rising 1630–32 and forest enclosure

Although Royal forests were not technically commons, they were used as such from at least the 1500s onwards. By the 1600s, when Stuart Kings examined their estates to find new revenues, it had become necessary to offer compensation to at least some of those using the lands as commons when the forests were divided and enclosed. The majority of the disafforestation took place between 1629–40, during Charles I of England's Personal Rule. Most of the beneficiaries were Royal courtiers, who paid large sums to enclose and sublet the forests. Those dispossessed of the commons, especially recent cottagers and those who were outside of tenanted lands belonging to manors, were granted little or no compensation, and rioted in response.[20]

Parliamentary enclosure and open fields

During the 18th and 19th centuries, enclosures were by means of local acts of Parliament, called the Inclosure Acts. These parliamentary enclosures consolidated strips in the open fields into more cohesive units, and enclosed much of the remaining pasture commons or wastes. Parliamentary enclosures usually provided commoners with some other land in compensation for the loss of common rights, although often of poor quality and much smaller. Enclosure consisted of exchange in land, and an extinguishing of common rights. This allowed farmers consolidated and fenced off plots of land, in contrast to multiple small strips spread out and separated.

Parliamentary enclosure was also used for the division and privatisation of common "wastes" (in the original sense of uninhabited places), such as fens, marshes, heathland, downland, moors. Voluntary enclosure was also frequent at that time.[21]

At the time of the parliamentary enclosures, each manor had seen de facto consolidation of farms into multiple large landholdings. Multiple larger landholders already held the bulk of the land.[22] They 'held' but did not legally own in today's sense. They also had to respect the open field system rights, when demanded, even when in practice the rights were not widely in use. Similarly each large landholding would consist of scattered patches, not consolidated farms. In many cases enclosures were largely an exchange and consolidation of land, and exchange not otherwise possible under the legal system. It did also involve the extinguishing of common rights. Without extinguishment, one man in an entire village could unilaterally impose the common field system, even if everyone else did not desire to continue the practice. De jure rights were not in accord with de facto practice. With land one held, one could not formally exchange the land, consolidate fields, or entirely exclude others. Parliamentary enclosure was seen as the most cost-effective method of creating a legally binding settlement. This is because of the costs (time, money, complexity) of the barriers in the common law and in equity to extinguishing customary and long-use rights. Parliament required consent of the owners of 4⁄5 of affected (the copyholders and freeholders).

The primary benefits to large land holders came from increased value of their own land, not from expropriation.[23] Smaller holders could sell their land to larger ones for a higher price post enclosure.[24] There was not much evidence that the common rights were particularly valuable.[25] Protests against Parliamentary Enclosure continued, sometimes in Parliament itself, frequently in the villages affected, and sometimes as organised mass revolts.[26] Voluntary enclosure was frequent at that time.[21] Enclosed land was twice as valuable, a price which could be sustained only by its higher productivity.[27]

Marxist historians have focused on enclosure as a part of the class conflict that eventually eliminated the English peasantry and saw the emergence of the bourgeoisie. From this viewpoint, the English Civil War provided the basis for a major acceleration of enclosures. The parliamentary leaders supported the rights of landlords vis-a-vis the King, whose Star Chamber court, abolished in 1641, had provided the primary legal brake on the enclosure process. By dealing an ultimately crippling blow to the monarchy (which, even after the Restoration, no longer posed a significant challenge to enclosures) the Civil War paved the way for the eventual rise to power in the 18th century of what has been called a "committee of Landlords",[28] a prelude to the UK's parliamentary system. The economics of enclosures also changed. Whereas earlier land had been enclosed to make it available for sheep farming, by 1650 the steep rise in wool prices had ended.[29] Thereafter, the focus shifted to implementation of new agricultural techniques, including fertilizer, new crops, and crop rotation, all of which greatly increased the profitability of large-scale farms.[30] The enclosure movement probably peaked from 1760 to 1832; by the latter date it had essentially completed the destruction of the medieval peasant community.[31]

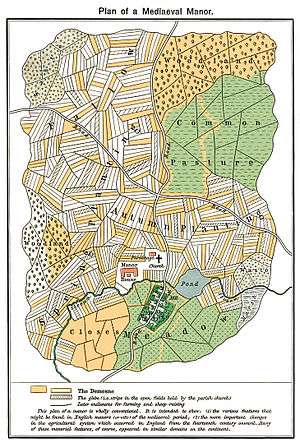

Before enclosure, much of the arable land in the central region of England was organised into an open field system. Enclosure was not simply the fencing of existing holdings, but led to fundamental changes in agricultural practice. Scattered holdings of strips in the common field were consolidated to create individual farms that could be managed independently of other holdings. Prior to enclosure, rights to use the land were shared between land owners and villagers (commoners). For example, commoners would have the right (common right) to graze their animals when crops or hay were not being grown, and on common pasture land. The land in a manor under this system would consist of:

- Two or three very large common arable fields

- Several very large common hay meadows

- Closes – small areas of enclosed private land such as paddocks, orchards or gardens, mostly near houses

- In some cases, a park around the principal house, the manor house

- Common waste – rough pasture land (effectively everything not in the previous categories)

Note that at this time field meant only the unenclosed and open arable land; most of what would now be called 'fields' would then have been called closes. The only boundaries would be those separating the various types of land, and around the closes.

In each of the two waves of enclosure, two different processes were used. One was the division of the large open fields and meadows into privately controlled plots of land, usually hedged and known at the time as severals. In the course of enclosure, the large fields and meadows were divided and common access restricted. Most open-field manors in England were enclosed in this manner, with the notable exception of Laxton, Nottinghamshire and parts of the Isle of Axholme in North Lincolnshire.

The history of enclosure in England is different from region to region.[32] Not all areas of England had open-field farming in the medieval period. Parts of south-east England (notably parts of Essex and Kent) retained a pre-Roman system of farming in small enclosed fields. Similarly in much of west and north-west England, fields were either never open, or were enclosed early. The primary area of open field management was in the lowland areas of England in a broad band from Yorkshire and Lincolnshire diagonally across England to the south, taking in parts of Norfolk and Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, large areas of the Midlands, and most of south central England. These areas were most affected by the first type of enclosure, particularly in the more densely settled areas where grazing was scarce and farmers relied on open field grazing after the harvest and on the fallow to support their animals.

The second form of enclosure affected those areas, such as the north, the far south-west, and some other regions such as the East Anglian Fens, and the Weald, where grazing had been plentiful on otherwise marginal lands, such as marshes and moors. Access to these common resources had been an essential part of the economic life in these strongly pastoral regions, and in the Fens, large riots broke out in the seventeenth century, when attempts to drain the peat and silt marshes were combined with proposals to partially enclose them.

Both economic and social factors drove the enclosure movement. In particular, the demand for land in the seventeenth century, increasing regional specialisation, engrossment in landholding and a shift in beliefs regarding the importance of "common wealth" (usually implying common livelihoods) as opposed to the "public good" (the wealth of the nation or the GDP) all laid the groundwork for a shift of support among elites to favour enclosure. Enclosures were conducted by agreement among the landholders (not necessarily the tenants) throughout the seventeenth century; enclosure by Parliamentary Act began in the eighteenth century. Enclosed lands normally could demand higher rents than unenclosed, and thus landlords had an economic stake in enclosure, even if they did not intend to farm the land directly.

While many villagers received plots in the newly enclosed manor, for small landholders this compensation was not always enough to offset the costs of enclosure and fencing. Many historians believe that enclosure was an important factor in the reduction of small landholders in England, as compared to the Continent, though others believe that this process had already begun from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Enclosure faced a great deal of popular resistance because of its effects on the household economies of smallholders and landless labourers. Common rights had included not just the right of cattle or sheep grazing, but also the grazing of geese, foraging for pigs, gleaning, berrying, and fuel gathering. During the period of parliamentary enclosure, employment in agriculture did not fall, but failed to keep pace with the growing population.[33] Consequently, large numbers of people left rural areas to move into the cities where they became labourers in the Industrial Revolution. Thus in a real way the English Parliament, seeking to increase profits on farm land also created the workers needed to increase the rapid expansion of the factory work force, by forcing people out of the surround county into cities.[34]

By the end of the 19th century enclosure had been carried out in most parishes, leaving a village green, any foreshore below the high-tide mark and occasionally a lower number of small common pastures.

Many landowners became rich through the enclosure of the commons, while many ordinary folk had a centuries-old right taken away. Land enclosure has been condemned as a gigantic swindle on the part of large landowners. In 1770 Oliver Goldsmith wrote The Deserted Village, deploring rural depopulation. An anonymous protest poem from the 17th century summed up the anti-enclosure feeling, and has been repeated in many variants since, even being applied to the contemporary privatization of the Internet:[35]

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common,

But lets the greater felon loose

Who steals the common from the goose.[36]

George Orwell wrote in 1944:

Stop to consider how the so-called owners of the land got hold of it. They simply seized it by force, afterwards hiring lawyers to provide them with title-deeds. In the case of the enclosure of the common lands, which was going on from about 1600 to 1850, the land-grabbers did not even have the excuse of being foreign conquerors; they were quite frankly taking the heritage of their own countrymen, upon no sort of pretext except that they had the power to do so.[37]

In April 1772, a paper signed "near Dorchester", was addressed to the King (the newspapers taking notice of His Majesty's desire to see the price of provisions lowered), to lay before him the evils of forestalling and engrossing. As examples of engrossing in the neighbourhood of Dorchester, the writer instances the manors of Came, Whitcomb, Muncton, and Bockhampton. The first, he says, about thirty years before, had many inhabitants, many holding leasehold estates under the lord of the manor for three lives. Some of these had estates of 15l.,[lower-alpha 1] 20l.,[lower-alpha 2] and 30l a year, being for the most part careful, industrious people, obliged to be careful to keep a little cash to keep the estate in the family if a life should drop. Their corn was brought to market, and they were content with the market price. Their cattle were sold in the same manner.

Their children when of proper age were married, and children begotten, without fear of poverty. But the lord had since turned out all the people, and the whole place was in his own hands, while not half the quantity of corn was sown that formerly had been. The writer also gives an account how one Wm. Taunton, though only a tenant of the Dean and Chapter of Exon, was gradually getting the whole parish into his own hands. He says, comparing his own with past times, that formerly a farmer that occupied 100l. a year was thought a tolerable one, and he that occupied four or five hundred pounds a very great one indeed; but now they had farmers that occupied from one thousand to two thousand per annum, who did not want money to pay their rent, as did the little farmers, who were obliged to sell their corn, etc. The writer gives it as the general opinion that the kingdom had become greatly depopulated, some averring the population to have decreased by a fourth within the preceding hundred years. He further says:

Your Majesty must put a stop to inclosures, or oblige ye lord of ye manor to keep up ye antient custom of it, and not suffer him to buy his tenant's interest; to have all the houses pulled down, and ye whole parish turn'd into a farm: this is a fashionable practice, and by none more yn Jn° Damer, Esq., ye owner of Came, and his brother Lord Milton.[38]

Enclosure roads

Public roads through enclosed common land were made to an accepted width between boundaries. In the late eighteenth century this was at least 60 feet (18 m), but from the 1790s this was decreased to 40 feet (12 m), and later 30 feet as the normal maximum width. The reason for these wide roads to was to prevent excessive churning of the road bed, and allow easy movement of flocks and herds of animals.[39]

Contemporary worldwide movements against enclosure

- Abahlali baseMjondolo in South Africa

- The Bhumi Uchhed Pratirodh Committee in India

- The Zapatista Army of National Liberation in Mexico

- Fanmi Lavalas in Haiti

- The Free Software Foundation

- The Homeless Workers' Movement in Brazil

- The Landless Peoples Movement in South Africa

- The Landless Workers' Movement in Brazil

- Narmada Bachao Andolan in India

- The Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign in South Africa

See also

Notes

- equivalent to £1,932 in 2019.

- equivalent to £2,575 in 2019.

- The Cultural Landscape: An Introduction to Human Geography, James M. Rubenstein, Pearson Publishing (2011)

- Karl Marx. "Chapter 27 Das Kapital". Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- Thompson, E.P. (1964). The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 198. LCCN 64-10769. OCLC 178185.

- Thompson 1991, p. 237.

- A comparison of the English historical enclosures with the (much later) German 19th century Landflucht. Engels, Friedrich (1882). Die Mark (in German). Die Entwicklung des Sozialismus von der Utopie zur Wissenschaft. Hottingen (Zurich). Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich. Werke (in German) (1973 reprint of 196t 1st ed.). Berlin: Karl Dietz.

- Chambers & Mingay 1982, p. 104.

- Armstrong 1981, p. 80.

- Hey 2008, pp. 177–240.

- Overton 1996, pp. 165

- Overton, Mark (1996). Agricultural Revolution in England: The transformation if the agrarian economy 1500–1850. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56859-3.

- Marx, Karl. "Capital Volume I, Ch. 27 The Expropriation of the Agricultural Population". Penguin Classics, 1990 [1867]. Trans. Ben Fowkes.

- Hammond & Hammond 1912, pp. 4–5.

- Beresford 1998, p. 28.

- More, Thomas - Utopia (1901 translation),

- Holeton, David R. "Fynes Moryson's Itinerary: A Sixteenth Century English Traveller's Observations on Bohemia, its Reformation, and its Liturgy" (PDF). The Bohemian Reformation and Religious Practice. Prague. pp. 379–410. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Beresford 1998, pp. 102 et seq.

- Thirsk, Joan (1984). The Rural Economy of England. History series. 25. A&C Black. p. 71. ISBN 9780826444424. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

[O]nly the overwhelming compulsion of population increase, together with accompanying price rises, can explain why enclosure made such swift progress and was such a burning issue in two separate periods […], the sixteenth and late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

- Thirsk 1958, p. 9.

- Monbiot, George (22 February 1995). "A Land Reform Manifesto". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Buchanan Sharp (1980), In contempt of all authority, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-03681-6, OL 4742314M, 0520036816

- McCloskey 1975, pp. 146.

- McCloskey 1975, pp. 149–50.

- McCloskey 1975, pp. 128–133.

- McCloskey 1975, pp. 147.

- McCloskey 1975, pp. 142–144.

- Hammond J.L. and Barbara, The Village Labourer 1760–1832

- McCloskey 1975, pp. 156.

- Moore 1966, pp. 17, 19–29.

- Moore 1966, p. 7.

- Moore 1966, p. 23.

- Moore 1966, pp. 25–29.

- Thirsk 1958, p. 4.

- Chambers & Mingay 1982, p. 99.

- "Industrial Revolution". www.let.leidenuniv.nl. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Bastick, Zach (2012). "Our Internet and Freedom of Speech 'Hobbled by History': Introducing Plural Control Structures Needed to Redress a Decade of Linear Policy" (PDF). European Commission: European Journal of EPractice. Policy lessons from a decade of eGovernment, eHealth & eInclusion (15): 97–111.

- "The Goose and the Commons". wealthandwant.com. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Orwell, George (18 August 1944). "On the Origins of Property in Land". cooperativindividualism.org. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Watt, Robert, ed. (1772). "A letter to a Member of Parliament on the present High Price of P.s". Bibliotheca Britannica. Calendar of Home Office Papers, 1770–1772. p. 479. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Transforming Fell and Valley, Ian Whyte. Published by Centre for North West regional Studies, University of Lancaster 2003

References

- Armstrong, W A (1981). The Influence of Demographic Factors on the Position of the Agricultural Labourer in England and Wales, c.1750–1914". in "Agricultural History Review.". The Agricultural History Review. 29. British Agricultural History Society. pp. 71–82.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beresford, Maurice (1998). The Lost Villages of England (Revised ed.). Sutton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chambers, J. D.; Mingay, G. E. (1982). The Agricultural Revolution 1750–1850 (Reprinted ed.). Batsford.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Court, W. H. B. (1954). A Concise Economic History of Britain. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hammond, J. L.; Hammond, Barbara (1912). The Village Labourer 1760–1832. London: Longman.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hey, David; Halstead, John L.; Hoyle, R. W.; Short, Brian M. (2008). David Hey (ed.). Themes in The Oxford Companion to Family and Local History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-53298-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnson, Arthur H. (1909). The Disappearance of the Small Landowner. Oxford: Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kropotkin, Peter (1902). "7. Mutual aid amongst ourselves". Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. Retrieved 4 March 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lindley, Keith (1982). Fenland Riots and the English Revolution.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCloskey, Donald. (1975) "Economics of enclosure: a market analysis." pp 123-160 in European Peasants and their Markets: essays in Agrarian Economic History edited by W. N. Parker & E.L. Jones. eds (1975). online

- Moore, Barrington (1966). Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neeson, J. M. (1993). Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700–1820. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56774-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Polanyi, Karl (1944). The Great Transformation.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaw-Taylor, Leigh (2001). "Parliamentary Enclosure and the Emergence of an English Agricultural Proletariat". Journal of Economic History. 61 (3): 640–662. JSTOR 2698131.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thirsk, Joan (1958). Tudor Enclosures (oft reprinted ed.). The Historical Association.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, E. P. (1991). The Making of the English Working Class. Penguin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Beckett, J. V. (1991). "The Disappearance of the Cottager and the Squatter from the English Countryside: The Hammonds Revisited.". In Holderness, B. A.; Turner, Michael (eds.). Land, Labour and Agriculture, 1700 1920. London: Hambledon Press.

- Chambers, Jonathan D. "Enclosure and labour supply in the industrial revolution." Economic History Review 5.3 (1953): 319-343. in JSTOR

- Dahlman, Carl J (1980). The Open Field System and Beyond: A Property Rights Analysis of an Economic Institution. Cambridge University Press.

- Everitt, Alan (2000). "Common Land". In Thirsk, Joan (ed.). The English Rural Landscape. Oxford University Press.

- Gonner, E. C. K (1912). Common Land and Inclosure. London: Macmillan & Co.

- Humphries, J. (1990). "Enclosures, commons rights, and women". Journal of Economic History. 50 (1): 17–42. doi:10.1017/s0022050700035701.

- McCloskey, Donald N. "The enclosure of open fields: Preface to a study of its impact on the efficiency of English agriculture in the eighteenth century." Journal of Economic History 32.1 (1972): 15-35 online.

- Thirsk, Joan (29 December 1964). "The Common Fields". Past and Present. pp. 3 25.

- Literary references

- Judt, Tony (25 March 2010). Ill Fares the Land. Allen Lane/Penguin. ISBN 978-1-84614-359-5. (Title taken from Goldsmith's work The Deserted Village)

- Marx, Karl. "27. Expropriation of the Agricultural Population from the Land". Das Kapital [Capital]. Marxists.org (in German). 1. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- The Yellow Admiral by Patrick O'Brian

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Enclosure |

| Look up enclosure in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up champaign in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |