Diet in Hinduism

Diet in Hinduism varies with its diverse traditions. The ancient and medieval Hindu texts recommend ahimsa—non-violence against all life forms including animals because they believe that it minimizes animal deaths.[1][2] Many Hindus follow a vegetarian diet (that may or may not include eggs and dairy products), that they believe is in sync with nature, compassionate, respectful of other life forms.[1]

Diet of non-vegetarian Hindus can include fish, poultry and goat meat in addition to eggs and dairy products. For slaughtering animals and birds for food, meat-eating Hindus often favor jhatka (quick death) style preparation of meat since Hindus believe that this method minimizes trauma and suffering to the animal.[3][4] Ancient Hindu texts describe the whole of creation as a vast food chain, and the cosmos as a giant food cycle.[5]

Hindu mendicants (sannyasin) avoid preparing their own food, relying either on alms or harvesting seeds and fruits from forests, as they believe this minimizes the likely harm to other life forms and nature.[5]

Food in the Vedas

The Vedic texts have conflicting verses, which scholars have interpreted to mean support or opposition to meat-based food. [6] The hymn 10.87.16 of the Hindu scripture Rigveda (~1200–1500 BCE), states Nanditha Krishna, condemns all killings of men, cattle and horses, and prays to god Agni to punish those who kill.[7][8] According to Harris, from ancient times, vegetarianism became a well accepted mainstream Hindu tradition.[6][9]

Food in Upanishads, Samhitas and Sutras

The Upanishads and Sutra texts of Hinduism discuss moderate diet and proper nutrition,[10] as well as Aharatattva (dietetics).[11] The Upanishads and Sutra texts invoke the concept of virtuous self-restraint in matters of food, while the Samhitas discuss what and when certain foods are suitable. A few Hindu texts such as Hathayoga Pradipika combine both.[12]

Moderation in diet is called Mitahara, and this is discussed in Shandilya Upanishad,[13] as well as by Svātmārāma as a virtue.[10][14][15] It is one of the yamas (virtuous self restraints) discussed in ancient Indian texts.[note 1]

Some of the earliest ideas behind Mitahara trace to ancient era Taittiriya Upanishad, which in various hymns discusses the importance of food to healthy living, to the cycle of life,[17] as well as to its role in one's body and its effect on Self (Atman, Spirit).[18] The Upanishad, states Stiles,[19] notes “from food life springs forth, by food it is sustained, and in food it merges when life departs”.

Many ancient and medieval Hindu texts debate the rationale for a voluntary stop to cow slaughter and the pursuit of vegetarianism as a part of a general abstention from violence against others and all killing of animals.[20][21] Some significant debates between pro-non-vegetarianism and pro-vegetarianism, with mention of cattle meat as food, is found in several books of the Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, particularly its Book III, XII, XIII and XIV.[20] It is also found in the Ramayana.[21] These two epics are not only literary classics, but they have also been popular religious classics.[22]

The Bhagavad Gita includes verses on diet and moderation in food in Chapter 6. It states in verse 6.16 that a Yogi must neither eat too much nor too little, neither sleep too much nor too little.[23] Understanding and regulating one's established habits about eating, sleeping and recreation is suggested as essential to the practice of yoga in verse 6.17.[23][24]

Another ancient Indian text, Tirukkuṛaḷ, originally written in the South Indian language of Tamil, states moderate diet as a virtuous lifestyle and criticizes "non-vegetarianism" in its Pulaan Maruthal (abstinence from flesh or meat) chapter, through verses 251 through 260.[25] Verse 251, for instance, questions "how can one be possessed of kindness, who, to increase his own flesh, eats the flesh of other creatures." It also says that "the wise, who are devoid of mental delusions, do not eat the severed body of other creatures" (verse 258), suggesting that "flesh is nothing but the despicable wound of a mangled body" (verse 257). It continues to say that not eating meat is a practice more sacred than the most sacred religious practices ever known (verse 259) and that only those who refrain from killing and eating the kill are worthy of veneration (verse 260). This text, written before 400 CE, and sometimes called the Tamil Veda, discusses eating habits and its role in a healthy life (Mitahara), dedicating Chapter 95 of Book 7 to it.[26] Tirukkuṛaḷ states in verses 943 through 945, "eat in moderation, when you feel hungry, foods that are agreeable to your body, refraining from foods that your body finds disagreeable". Tiruvalluvar also emphasizes overeating has ill effects on health, in verse 946, as “the pleasures of health abide in the man who eats moderately. The pains of disease dwell with him who eats excessively.”[26][27]

Verses 1.57 through 1.63 of the Hathayoga Pradipika suggests that taste cravings should not drive one's eating habits, rather the best diet is one that is tasty, nutritious and likable as well as sufficient to meet the needs of one's body and for one's inner self.[28] It recommends that one must "eat only when one feels hungry" and "neither overeat nor eat to completely fill the capacity of one's stomach; rather leave a quarter portion empty and fill three quarters with quality food and fresh water".[28] Verses 1.59 to 1.61 of Hathayoga Pradipika suggest a mitahara regimen of a yogi avoids foods with excessive amounts of sour, salt, bitterness, oil, spice burn, unripe vegetables, fermented foods or alcohol. The practice of Mitahara, in Hathayoga Pradipika, includes avoiding stale, impure and tamasic foods, and consuming moderate amounts of fresh, vital and sattvic foods.[29]

Diet in ancient Hindu texts on health

Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita – two major ancient Hindu texts on health-related subjects, include many chapters on the role of diet and personal needs of an individual. In Chapter 10 of Sushruta Samhita, for example, the diet and nutrition for pregnant women, nursing mothers, and young children are described.[30] It recommends milk, butter, fluid foods, fruits, vegetables and fibrous diets for expecting mothers along with soups made from jangala (wild) meat.[31] In most cases, vegetarian diets are preferred and recommended in the Samhitas; however, for those recovering from injuries, growing children, those who do high levels of physical exercise, and expecting mothers, Sutrasthanam's Chapter 20 and other texts recommend carefully prepared meat. Sushruta Samhita also recommends a rotation and balance in foods consumed, in moderation.[30] For this purposes, it classifies foods by various characteristics, such as taste. In Chapter 42 of Sutrasthanam, for example, it lists six tastes – madhura (sweet), amla (acidic), lavana (salty), katuka (pungent), tikta (bitter) and kashaya (astringent). It then lists various sources of foods that deliver these tastes and recommends that all six tastes (flavors) be consumed in moderation and routinely, as a habit for good health.[32]

Food in the Dharmaśāstras

According to Kane, one who is about to eat food should greet the food when it is served to him, should honour it, never speak ill, and never find fault in it.[5][33]

The Dharmasastra literature, states Patrick Olivelle, admonishes "people not to cook for themselves alone", offer it to the gods, to forefathers, to fellow human beings as hospitality and as alms to the monks and needy.[5] Olivelle claims all living beings are interdependent in matters of food and thus food must be respected, worshipped and taken with care.[5] Olivelle states that the Shastras recommend that when a person sees food, he should fold his hands, bow to it, and say a prayer of thanks.[5] This reverence for food reaches a state of extreme in the renouncer or monk traditions in Hinduism.[5] The Hindu tradition views procurement and preparation of food as necessarily a violent process, where other life forms and nature are disturbed, in part destroyed, changed and reformulated into something edible and palatable. The mendicants (sannyasin, ascetics) avoid being the initiator of this process, and therefore depend entirely on begging for food that is left over of householders.[5] In pursuit of their spiritual beliefs, states Olivelle, the "mendicants eat other people's left overs".[5] If they cannot find left overs, they seek fallen fruit or seeds left in field after harvest.[5]

The forest hermits of Hinduism, on the other hand, do not even beg for left overs.[5] Their food is wild and uncultivated. Their diet would consist mainly of fruits, roots, leaves, and anything that grows naturally in the forest.[5] They avoided stepping on plowed land, lest they hurt a seedling. They attempted to live a life that minimizes, preferably eliminates, the possibility of harm to any life form.[5]

Manusmriti

The Manusmriti discusses diet in chapter 5, where like other Hindu texts, it includes verses that strongly discourage meat eating, as well as verses where meat eating is declared appropriate in times of adversity and various circumstances, recommending that the meat in such circumstances be produced with minimal harm and suffering to the animal.[34] The verses 5.48-5.52 of Manusmriti explain the reason for avoiding meat as follows (abridged),

One can never obtain meat without causing injury to living beings... he should, therefore, abstain from meat. Reflecting on how meat is obtained and on how embodied creatures are tied up and killed, he should quit eating any kind of meat... The man who authorizes, the man who butchers, the man who slaughters, the man who buys or sells, the man who cooks, the man who serves, and the man who eats – these are all killers. There is no greater sinner than a man who, outside of an offering to gods or ancestors, wants to make his own flesh thrive at the expense of someone else's.

In contrast, verse 5.33 of Manusmriti states that a man may eat meat in a time of adversity, verse 5.27 recommends that eating meat is okay if not eating meat may place a person's health and life at risk, while various verses such as 5.31 and 5.39 recommend that the meat be produced as a sacrifice (Jhatka method).[34] In verses 3.267 to 3.272, Manusmriti approves of fish and meats of deer, antelope, poultry, goat, sheep, rabbit and others as part of sacrificial food.[35] In an exegetical analysis of Manusmriti, Patrick Olivelle states that the document shows opposing views on eating meat was common among ancient Hindus, and that underlying emerging thought on appropriate diet was driven by ethic of non-injury and spiritual thoughts about all life forms, the trend being to reduce the consumption of meat and favour a non-injurious vegetarian lifestyle.[36]

Food and ethics

Hinduism does not explicitly prohibit eating meat, but it does strongly recommend ahimsa – the concept of non-violence against all life forms including animals.[1][2] As a consequence, many Hindus prefer a vegetarian or lacto-vegetarian lifestyle, and methods of food production that are in harmony with nature, compassionate, and respectful of other life forms as well as nature.[1]

Vegetarian diet

India is a strange country. People do not kill

any living creatures, do not keep pigs and fowl,

and do not sell live cattle.

—Faxian, 4th/5th century CE

Chinese pilgrim to India[37]

Hinduism does not require a vegetarian diet,[38] but some Hindus avoid eating meat because it minimizes hurting other life forms.[39] Vegetarianism is considered satvic, that is purifying the body and mind lifestyle in some Hindu texts.[40][41]

Lacto-vegetarianism is favored by many Hindus, which includes milk-based foods and all other non-animal derived foods, but it excludes meat and eggs.[42] There are three main reasons for this: the principle of nonviolence (ahimsa) applied to animals,[43] the intention to offer only vegetarian food to their preferred deity and then to receive it back as prasad, and the conviction that non-vegetarian food is detrimental for the mind and for spiritual development.[40][44] Many Hindus point to scriptural bases, such as the Mahabharata's maxim that "Nonviolence is the highest duty and the highest teaching",[45] as advocating a vegetarian diet.

A typical modern urban Hindu lacto-vegetarian meal is based on a combination of grains such as rice and wheat, legumes, green vegetables, and dairy products.[46] Depending on the geographical region the staples may include millet based flatbreads. Fat derived from slaughtered animals is avoided.[47]

A number of Hindus, particularly those following the Vaishnav tradition, refrain from eating onions and garlic during Chaturmas period (roughly July - November of Gregorian calendar).[48] In Maharashtra, a number of Hindu families also do not eat any egg plant (Brinjal / Aubergine) preparations during this period.[49]

The followers of ISKCON (International Society for Krishna Consciousness, Hare Krishna) abstain from meat, fish, and fowl. The related Pushtimargi sect followers also avoid certain vegetables such as onion, mushrooms and garlic, out of the belief that these are tamas (harmful).[47][50] Swaminarayan movement members staunchly adhere to a diet that is devoid of meat, eggs, and seafood.[51]

Diet on fasting days

Hindu people fast on days such as Ekadashi, in honour of Lord Vishnu or his Avatars, Chaturthi in honour of Ganesh, Mondays in honour of Shiva, or Saturdays in honour of Maruti or Saturn.[52] Only certain kinds of foods are allowed to be eaten during the fasting period. These include milk and other dairy products such as dahi, fruit and starchy Western food items such as sago,[53] potatoes,[54] purple-red sweet potatoes, amaranth seeds,[55] nuts and shama millet.[56] Popular fasting dishes include Farari chevdo, Sabudana Khichadi or peanut soup.[57]

Non-vegetarian diet

Although some Hindus are vegetarians, a large proportion consume eggs, fish, chicken and meat. According to a survey, 13% of all non-vegetarians in India are Hindus,[58] although another survey suggests a much larger fraction. According to an estimate, only about 10% of Hindus in Suriname are vegetarians and less than five percent of Hindus in Guyana are vegetarians.[59]

Non-vegetarian Indians mostly prefer poultry, fish, other seafood, goat, and sheep as their sources of meat.[60] In the Bengal and Assam regions, fish is a staple of most communities. Fish is also the staple in coastal south-western India. It should, however, be noted that in other parts of India, even meat-eating Hindus have lacto-vegetarian meals on most days.[61] [62] Overall, India consumes the least amount of meat per capita.[63]

Hindus who do eat meat, often distinguish all other meat from beef. The respect for cow is part of Hindu belief, and most Hindus avoid meat sourced from cow[47] as cows are treated as a motherly giving animal,[47] considered as another member of the family.[64] A small minority of Nepalese Hindu sects sacrificed buffalo at the Gadhimai festival, but consider cows different from buffalo or other red meat sources. However, the sacrifice of buffalo was banned by the Gadhimai Temple Trust in 2015.[65][66]

The Cham Hindus of Vietnam also do not eat beef and pork.[67][68]

Some Hindus who eat non-vegetarian food abstain from eating non-vegetarian food during auspicious days like Dussera, Janmastami, Diwali, etc.[69]

Method of slaughter

The preferred production method for meat is the Jhatka method, a quick and painless death to the animal.[3] Many Indians who eat meat, require the Jhatka processing method, though mostly Hindus avoid meat. Among the Hindus of Nepal, annual festivals mark the sacrifice of goats, pigs, buffalo, chickens and other animals, and ritually produced Jhatka meat is consumed.[70]

See also

- Buddhist vegetarianism

- Christian dietary laws

- Diet in Sikhism

- Etiquette of Indian dining

- Indian vegetarian cuisine

- Islamic dietary laws

- Kashrut (Jewish Dietary Laws)

- List of diets

- Vegetarian cuisine

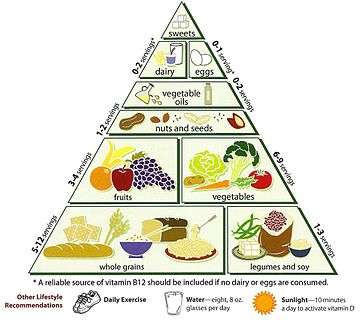

- Vegetarian Diet Pyramid

- Vegetarianism and religion

Note

- The other nine yamas are Ahinsā (अहिंसा): Nonviolence, Satya (सत्य): truthfulness, Asteya (अस्तेय): not stealing, Brahmacharya (ब्रह्मचर्य): celibacy and not cheating on one’s spouse, Kṣhamā (क्षमा): forgiveness,[16] Dhṛti (धृति): fortitude, Dayā (दया): compassion,[16] Ārjava (आर्जव): sincerity, non-hypocrisy, and Śauca (शौच): purity, cleanliness.

References

- Susan Dudek (2013), Nutrition Essentials for Nursing Practice, Wolters Kluwer Health, ISBN 978-1451186123, page 251

- Angela Wood (1998), Movement and Change, Nelson Thornes, ISBN 978-0174370673, page 80

- Das, Veena (13 February 2003). The Oxford India companion to sociology and social anthropology, Volume 1. 1. OUP India. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-19-564582-8.

- Neville Gregory and Temple Grandin (2007), Animal Welfare and Meat Production, CABI, ISBN 978-1845932152, pages 206-208

- Patrick Olivelle (1991), From feast to fast: food and the Indian Ascetic, in Medical Literature from India, Sri Lanka, and Tibet (Editors: Gerrit Jan Meulenbeld, Julia Leslie), BRILL, ISBN 978-9004095229, pages 17-36

- Marvin Harris (1990), India's sacred cow, Anthropology: contemporary perspectives, 6th edition, Editors: Phillip Whitten & David Hunter, Scott Foresman, ISBN 0-673-52074-9, pages 201-204

- Krishna, Nanditha (2014), Sacred Animals of India, Penguin Books Limited, pp. 15, 33, ISBN 978-81-8475-182-6

- ऋग्वेद: सूक्तं १०.८७, Wikisource, Quote: "यः पौरुषेयेण क्रविषा समङ्क्ते यो अश्व्येन पशुना यातुधानः । यो अघ्न्याया भरति क्षीरमग्ने तेषां शीर्षाणि हरसापि वृश्च ॥१६॥"

- Lisa Kemmerer (2011). Animals and World Religions. Oxford University Press. pp. 59–68 (Hinduism), pp. 100–110 (Buddhism). ISBN 978-0-19-979076-0.

- Svātmārāma; Pancham Sinh (1997). The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (5 ed.). Forgotten Books. p. 14. ISBN 9781605066370.

Quote - अथ यम-नियमाः

अहिंसा सत्यमस्तेयं बरह्यछर्यम कश्हमा धृतिः

दयार्जवं मिताहारः शौछम छैव यमा दश - Caraka Samhita Ray and Gupta, National Institute of Sciences, India, pages 18-19

- Hathayoga Pradipika Brahmananda, Adyar Library, The Theosophical Society, Madras India (1972)

- KN Aiyar (1914), Thirty Minor Upanishads, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 978-1164026419, Chapter 22, pages 173-176

- Lorenzen, David (1972). The Kāpālikas and Kālāmukhas. University of California Press. pp. 186–190. ISBN 978-0520018426.

- Subramuniya (2003). Merging with Śiva: Hinduism's contemporary metaphysics. Himalayan Academy Publications. p. 155. ISBN 9780945497998. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- Stuart Sovatsky (1998), Words from the Soul: Time East/West Spirituality and Psychotherapeutic Narrative, State University of New York, ISBN 978-0791439494, page 21

- Annamaya Kosa Taittiriya Upanishad, Anuvaka II, pages 397-406

- Realization of Brahman Taittiriya Upanishad, Anuvaka II & VII, pages 740-789; This is extensively discussed in these chapters; Illustrative quote - "Life, verily, is food; the body the food-eater" (page 776)

- M Stiles (2008), Ayurvedic Yoga Therapy, Lotus Press, ISBN 978-0940985971, pages 56-57

- Ludwig Alsdorf (2010). The History of Vegetarianism and Cow-Veneration in India. Routledge. pp. 32–44 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-135-16641-0.

- John R. McLane (2015). Indian Nationalism and the Early Congress. Princeton University Press. pp. 271–280 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-4008-7023-3.

- John McLaren; Harold Coward (1999). Religious Conscience, the State, and the Law: Historical Contexts and Contemporary Significance. State University of New York Press. pp. 199–204. ISBN 978-0-7914-4002-5.

- Paul Turner (2013), FOOD YOGA - Nourishing Body, Mind & Soul, 2nd Edition, ISBN 978-0985045111, page 164

- Stephen Knapp, The Heart of Hinduism: The Eastern Path to Freedom, Empowerment and Illumination, ISBN 978-0595350759, page 284

- Tirukkural, Translated by GU Pope et al., WH Allen, London, verses 251-260, pages 31-32, and pages 114-115, 159

- Tirukkuṛaḷ see Chapter 95, Book 7

- Tirukkuṛaḷ Translated by V.V.R. Aiyar, Tirupparaithurai: Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam (1998)

- KS Joshi, Speaking of Yoga and Nature-Cure Therapy, Sterling Publishers, ISBN 978-1845570453, page 65-66

- Steven Rosen (2011), Food for the Soul: Vegetarianism and Yoga Traditions, Praeger, ISBN 978-0313397035, pages 25-29

- KKL Bhishagratna, Chapter X, Sushruta Samhita, Vol 2, Calcutta, page 216-238

- Sushruta Samhita KKL Bhishagratna, Vol 2, Calcutta, page 217

- KKL Bhishagratna, Sutrasthanam, Chapter XLII Sushruta Samhita, Vol 1, Calcutta, page 385-393

- Kane, History of the Dharmaśāstras Vol. 2, p. 762

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195171464, pages 139-141

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195171464, page 122

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195171464, pages 279-280

- Anand M. Saxena (2013). The Vegetarian Imperative. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 201–202. ISBN 978-14214-02-420.

- Madhulika Khandelwal (2002), Becoming American, Being Indian, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0801488078, pages 38-39

- Steven Rosen, Essential Hinduism, Praeger, ISBN 978-0275990060, page 187

- N Lepes (2008), The Bhagavad Gita and Inner Transformation, Motilal Banarsidass , ISBN 978-8120831865, pages 352-353

- Michael Keene (2002), Religion in Life and Society, Folens Limited, p. 122, ISBN 978-1-84303-295-3, retrieved May 18, 2009

- Paul Insel (2013), Discovering Nutrition, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, ISBN 978-1284021165, page 231

- Tähtinen, Unto: Ahimsa. Non-Violence in Indian Tradition, London 1976, p. 107-109.

- Mahabharata 12.257 (note that Mahabharata 12.257 is 12.265 according to another count); Bhagavad Gita 9.26; Bhagavata Purana 7.15.7.

- Mahabharata 13.116.37-41

- Sanford, A Whitney."Gandhi's agrarian legacy: practicing food, justice, and sustainability in India". Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 7 no 1 Mr 2013, p 65-87.

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2004), Intercultural Education: Ethnographic and Religious Approaches, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1845190347, pages 25-27

- J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: L-Z. ABC-CLIO. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-1-59884-205-0.

- B. V. Bhanu (2004). People of India: Maharashtra. Popular Prakashan. p. 851. ISBN 978-81-7991-101-3.

- Narayanan, Vasudha. “The Hindu Tradition”. In A Concise Introduction to World Religions, ed. Willard G. Oxtoby and Alan F. Segal. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007

- Williams, Raymond. An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism. 1st. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. 159

- Dalal 2010, p. 6.

- Arnott, editor Margaret L. (1975). Gastronomy : the anthropology of food and food habitys. The Hague: Mouton. p. 319. ISBN 978-9027977397. Retrieved 31 October 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Walker, ed. by Harlan (1997). Food on the move : proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1996, [held in September 1996 at Saint Antony's College, Oxford]. Devon, England: Prospect Books. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-907325-79-6. Retrieved 31 October 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Amaranth: Modern Prospects for an Ancient Crop. National Academies. 1984. p. 6. NAP:14295.

- Dalal 2010, p. 7.

- Dalal 2010, p. 63.

- CHAKRAVARTI, A.K (2007). "Cultural dimensions of diet and disease in india.". City, Society, and Planning: Society. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 151–. ISBN 978-81-8069-460-8.

- "Hindus of South America".

- Ridgwell and Ridgway (1987), Food Around the World, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0198327288, page 67

- Puskar-Pasewicz, Margaret, ed. (2010). Cultural encyclopedia of vegetarianism. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood. p. 40. ISBN 978-0313375569. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Speedy, A.W., 2003. Global production and consumption of animal source foods. The Journal of nutrition, 133(11), pp.4048S-4053S.

- Devi, S.M., Balachandar, V., Lee, S.I. and Kim, I.H., 2014. An outline of meat consumption in the Indian population-A pilot review. Korean journal for food science of animal resources, 34(4), p.507.

- Bhaskarananda, Swami (2002). The Essentials of Hinduism. Seattle: The Vedanta Society of Western Washington. p. 60. ISBN 978-1884852046.

- "Victory! Animal Sacrifice Banned at Nepal's Gadhimai Festival, Half a Million Animals Saved". July 28, 2015.

- "Did Nepal temple ban animal sacrifice festival?". July 31, 2015 – via www.bbc.com.

- Hays, Jeffrey. "CHAM | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com.

- "Selected Groups in the Republic of Vietnam: The Cham". www.ibiblio.org.

- "Why Hindus do not eat Non Vegetarian Food on particular days?". WordZz. September 10, 2016.

- Sarkar, Sudeshna (24 November 2009), "Indians throng Nepal's Gadhimai fair for animal sacrifice", The Times of India

Bibliography

- Olivelle (1999). From Feast to Fast: Food and the Indian Ascetic.

- Dalal, Tarla (2010). Faraal Foods for fasting days. Mumbai: Sanjay and Co. ISBN 9789380392028.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gupte, B. A. (1994). Hindu Holidays and Ceremonials: With Dissertations on Origin, Folklore and Symbols. Asian Educational Services. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-81-206-0953-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)