Transcaucasia

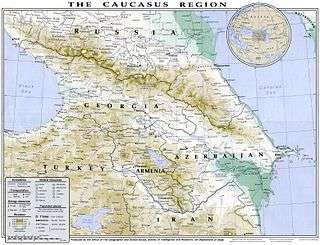

Transcaucasia (Russian: Закавказье, romanized: Zakavkazye; Armenian: Անդրկովկաս, romanized: Andrkovkas), also known as the South Caucasus (Azerbaijani: Cənubi Qafqaz, Ҹәнуби Гафгаз; Georgian: სამხრეთ კავკასია, romanized: Samkhret K’avk’asia; Russian: Южный Кавказ, romanized: Yuzhnyy Kavkaz), is a geographical region in the vicinity of the southern Caucasus Mountains on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia.[1][2] Transcaucasia roughly corresponds to modern Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The total area of these countries measures about 186,100 square kilometres (71,850 square miles).[3] Transcaucasia and Ciscaucasia (North Caucasus) together comprise the larger Caucasus geographical region that divides Eurasia.

Geography

Transcaucasia spans the southern portion of the Caucasus Mountains and their lowlands, straddling the border between the continents of Europe and Asia, and extending southwards from the southern part of the Greater Caucasus mountain range of southwestern Russia to the Turkish and Armenian borders, and from the Black Sea in the west to the Caspian Sea coast of Iran in the east. The area includes the southern part of the Greater Caucasus mountain range, the entire Lesser Caucasus mountain range, the Colchis Lowlands, the Kura-Aras Lowlands, Qaradagh, the Talysh Mountains, the Lankaran Lowland, Javakheti and the eastern portion of the Armenian Highland.

All of present-day Armenia is in Transcaucasia; the majority of present-day Georgia and Azerbaijan, including the exclave of Nakhchivan, also fall within the region. Parts of Iran and Turkey are also included within the region of Transcaucasia.[4] Goods produced in the region include oil, manganese ore, tea, citrus fruits, and wine. It remains one of the most politically tense regions in the post-Soviet area, and contains three heavily disputed areas: Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Nagorno-Karabakh. Between 1878 and 1917 the Russian-controlled province of Kars Oblast was also incorporated into the Transcaucasus.

Etymology

Transcaucasia is a Latin rendering of the Russian-language word Zakavkazye (Закавказье), meaning "the area beyond the Caucasus Mountains".[3] This implies a Russian vantage point, and is analogous to similar terms such as Transnistria and Transleithania. Other, rarer forms of this word include Trans-Caucasus and Transcaucasus (Russian: Транскавказ, romanized: Transkavkaz). The region is also referred to as Southern Caucasia and the South Caucasus.

History

Prehistory

Herodotus, Greek historian who is known as 'the Father of History' and Strabo, Greek geographer, philosopher, and historian spoke about autochthonous peoples of the Caucasus in their books. In the Middle Ages various peoples, including Scythians, Alani, Huns, Khazars, Arabs, Seljuq Turks, and Mongols settled in Caucasia. These invasions influenced on the culture of the peoples of Transcaucasia. In parallel Middle Eastern influence disseminated the Iranian languages and Islamic religion in Caucasus.[3]

Located on the peripheries of Iran, Russia and Turkey, the region has been an arena for political, military, religious, and cultural rivalries and expansionism for centuries. Throughout its history, the region has come under control of various empires, including the Achaemenid, Neo-Assyrian Empire,[5] Parthian, Roman, Sassanian, Byzantine, Mongol, Ottoman, successive Iranian (Safavid, Afsharid, Qajar), and Russian Empires, all of which introduced their faiths and cultures.[6] Throughout history, Transcaucasia was usually under the direct rule of the various in-Iran based empires and part of the Iranian world.[7] In the course of the 19th century, Qajar Iran had to irrevocably cede the region (alongside its territories in Dagestan, North Caucasus) as a result of the two Russo-Persian Wars of that century to Imperial Russia.[8]

Ancient kingdoms of the region included Armenia, Albania and Iberia, among others. These kingdoms were later incorporated into various Iranian empires, including the Achaemenid Empire, the Parthian Empire, and the Sassanid Empire, during which Zoroastrianism became the dominant religion in the region. However, after the rise of Christianity and conversion of Caucasian kingdoms to the new religion, Zoroastrianism lost its prevalence and only survived because of Persian power and influence still lingering in the region. Thus, Transcaucasia became the area of not only military, but also religious convergence, which often led to bitter conflicts with successive Persian empires (and later Muslim-ruled empires) on the one side and the Roman Empire (and later the Byzantine Empire) on the other side.

The Iranian Parthians established and installed several eponymous branches in Transcaucasia, namely the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia, the Arsacid dynasty of Iberia, and the Arsacid Dynasty of Caucasian Albania.

Middle ages and Russian rule

In the middle of the 8th century, with the capture of Derbend by the Umayyad armies during the Arab–Khazar wars, most of Transcaucasia became part of the Caliphate and Islam spread throughout the region.[9] Later, the Orthodox Christian Kingdom of Georgia dominated most of Transcaucasia. The region was then conquered by the Seljuk, Mongol, Turkic, Safavid, Ottoman, Afsharid and Qajar dynasties.

After two wars in the first half of the 19th century, namely the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813) and the Russo-Persian War (1826-1828), the Russian Empire conquered most of Transcaucasia (and Dagestan in the North Caucasus) from the Iranian Qajar dynasty, severing historic regional ties with Iran.[7][10] By the Treaty of Gulistan that followed after the 1804-1813 war, Iran was forced to cede modern-day Dagestan, Eastern Georgia, and most of the Azerbaijan Republic to Russia. By the Treaty of Turkmenchay that followed after the 1826-1828 war, Iran lost all of what is modern-day Armenia and the remainder of the contemporary Azerbaijani Republic that remained in Iranian hands. After the 1828-1829 war, the Ottomans ceded Western Georgia (except Adjaria, which was known as Sanjak of Batum), to the Russians.

In 1844, what comprises present-day Georgia, Armenia and the Azerbaijan Republic were combined into a single czarist government-general, which was termed a vice-royalty in 1844-1881 and 1905–1917. Following the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War, Russia annexed Kars, Ardahan, Agri and Batumi from the Ottomans, joined to this unit, and established the province of Kars Oblast as its most southwesterly territory in the Transcaucasus.

Modern era

After the fall of the Russian Empire in 1918, the Transcaucasia region was unified into a single political entity twice, as Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic from 9 April 1918 to 26 May 1918, and as Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic from 12 March 1922 to 5 December 1936, each time to be dissolved into three Soviet Socialist Republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. All three regained independence in 1991 when the Soviet Union dissolved.

The Russo-Georgian War took place in 2008 across Transcaucasia, contributing to further instability in the region, which is as intricate as the Middle East, due to the complex mix of religions (mainly Muslim and Orthodox Christian) and ethno-linguistic groups.

Since independence, the three countries have had varying degrees of success in their relations with Russia and other countries. In Georgia, after the Rose Revolution in 2004, the country, like the Baltic states, began integrating into Western Europe by opening up relations with NATO and the European Union. Armenia continues to foster relations with Russia while Azerbaijan relies less on Russia, strategically partnering with Turkey and other NATO states.

Wine

Transcaucasia, in particular where modern-day Turkey, Georgia, Armenia and Iran are located, is one of the native areas of the wine-producing vine Vitis vinifera.[11] Some experts speculate that Transcaucasia may be the birthplace of wine production.[12] Archaeological excavations and carbon dating of grape seeds from the area have dated back to 8000–5000 BC.[13] Wine found in Iran has been dated to c. 7400 BC[11] and c. 5000 BC,[14] while wine found in Georgia has been dated to c. 5,980 BC.[15][16][17] The earliest winery, dated to c. 4000 BC, was found in Armenia.[11]

See also

References

- "Caucasus". The World Factbook. Library of Congress. May 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- Mulvey, Stephen (16 June 2000). "The Caucasus: Troubled borderland". News. BBC. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

"The Caucasus Mountains form the boundary between West and East, between Europe and Asia..."

- Solomon Ilich Bruk. "Transcaucasia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Wright, John; Schofield, Richard; Goldenberg, Suzanne (16 December 2003). Transcaucasian Boundaries. Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 9781135368500.

- Albert Kirk Grayson (1972). Assyrian Royal Inscriptions: Volume I. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. p. 108. §716.

- German, Tracey (2012). Regional Cooperation in the South Caucasus: Good Neighbours Or Distant Relatives?. Ashgate Publishing Ltd. p. 44. ISBN 978-1409407218.

- "Caucasus and Iran" in Encyclopaedia Iranica, Multiple Authors

- Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond p 728-730 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- King, Charles (2008). The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0199884322.

- Allen F. Chew. An Atlas of Russian History: Eleven Centuries of Changing Borders. Yale University Press, 1967. pp 74

- But was it plonk?, Boston Globe

- Hugh Johnson Vintage: The Story of Wine pg 15 Simon & Schuster 1989

- Johnson pg 17

- Ellsworth, Amy (18 July 2012). "7,000 Year-old Wine Jar". Penn Museum.

- "'World's oldest wine' found in 8,000-year-old jars in Georgia". BBC. 13 November 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Berkowitz, Mark (1996). "World's Earliest Wine". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 49 (5). Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- Spilling, Michael; Wong, Winnie (2008). Cultures of The World: Georgia. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7614-3033-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South Caucasus. |

- Caucasian Journal — a multilingual online journal on the South Caucasus

- Caucasian Review of International Affairs - an academic journal on the South Caucasus

- Caucasus Analytical Digest - Journal on the South Caucasus

- Transcaucasia (The Columbia Encyclopedia article)