Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic

The Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic (TDFR;[lower-alpha 1] April 22 – May 28, 1918), also known as the Transcaucasian Federation, was a short-lived South Caucasian state extending across what are now the modern-day countries of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, plus parts of Eastern Turkey as well as Russian border areas. The state only lasted for a month before Georgia declared independence, followed shortly by Azerbaijan and Armenia.

Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic Закавказская демократическая федеративная республика | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918 | |||||||||||||

Flag | |||||||||||||

Transcaucasia immediately prior to the formation of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Tiflis | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Official: Armenian Azerbaijani Georgian Russian | ||||||||||||

| Government | Federative republic | ||||||||||||

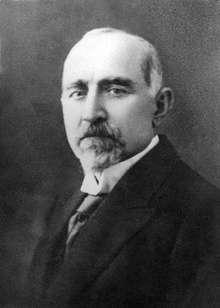

• President | Nikolay Chkheidze | ||||||||||||

• Prime Minister | Akaki Chkhenkeli | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | World War I | ||||||||||||

• Federation proclaimed | April 22, 1918 | ||||||||||||

• Georgia declares independence | May 26, 1918 | ||||||||||||

• Independence of Armenia and Azerbaijan | May 28, 1918 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Transcaucasian ruble (ru) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

History

Background

The South Caucasus had been conquered by the Russian Empire early in the nineteenth century, with the last annexations taking place in 1828.[1] Over the next several decades the administration of the region was variously modified in order to consolidate Russian control over the region, and a Caucasian Viceroyalty was permanently establish in 1845 (similar roles had existed since 1801).[2] Tiflis (now Tbilisi) was the seat of the viceroy and the de facto capital of the region.[3] The South Caucasus was overwhelmingly rural: aside from Tiflis the only other city of significance was Baku.[4] Baku grew in the later part of the nineteenth century as oil began to be exported from the region, and became a major economic hub.[5]

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the Caucasus became a major theatre, with the Russian and Ottoman Empires fighting in the region.[6] While the Russians managed to win some early battles, the authorities were concerned that the local population, which had a large portion of Muslims, would turn and join the Ottoman forces, as the Ottoman Sultan was also the caliph, the spiritual leader of Islam.[7] In a similar vein, both sides wanted to use the Armenian population to their advantage.[8] However military defeats led the Ottoman to turn against the Armenians, and by 1915 launched the Armenian Genocide, in which an estimate 1.5 million Armenians were killed.[9][10]

The 1917 February Revolution saw the demise of the Russian Empire and the establishment of a provisional government in Russia. Grand Duke Nicholas, the Viceroy of the Caucasus, initially expressed his support for the new government, but was forced to resign his post.[11] A new authority, the Special Transcaucasian Committee (known as Ozakom, from the Russian Особый Закавказский Комитет; Osobyy Zakavkazskiy Komitet), was established on March 22, 1917. This was meant to function as a "collective viceroyalty," with members from the various ethnic groups of the region represented.[12] Much like in Petrograd, a dual power system was established, with the Ozakom competing with soviets (councils).[13] With little support from the government in Petrograd, the Ozakom had trouble establishing its authority over the soviets, most prominently the Tiflis Soviet.[14]

Sejm

In November 1917, following the October Revolution, the first government of an independent Transcaucasia was created in Tbilisi. A Transcaucasian Committee and a Transcaucasian Commissariat (Sejm, headed by the Georgian pro-Menshevik Social Democrat Nikolay Chkheidze) existed for a couple of months. On December 5, 1917, the Committee endorsed the Armistice of Erzincan signed by the Ottoman command of the Third Army.

Formation

On March 3, 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk marked the end of Russia's involvement in World War I. The Ottoman Empire regained Batum, Kars and Ardahan. Starting on March 14, the Trabzon peace conference was held between the Ottoman Empire and a delegation from the Sejm. By April 5, the head of the Transcaucasian delegation, Akaki Chkhenkeli, accepted the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk as a basis for more negotiations and urged the Transcaucasian governments to accept this position.[15] The mood in Tbilisi, however, was very different. Instead of being bound by the terms of Brest-Litovsk, the Sejm gathered and made the decision to establish independence. On April 22, 1918, it proclaimed the establishment of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. A state of war between the Republic and the Ottoman Empire was confirmed and, shortly afterwards, the Ottoman Third Army took Erzerum and Kars.[15]

A new peace conference was convened at Batum on May 11.[16] The Ottoman Empire extended its demands to include Tiflis as well as Alexandropol and Echmiadzin, where their leaders wanted to build a railroad to connect Kars and Julfa with Baku. No agreement was reached and, on May 21, the Ottoman forces resumed their advance. The battles of Bash Abarn (May 21–24), Sardarapat (May 21–29) and Kara Killisse (May 24–28) followed.

Dissolution

The republic never had a strong foundation. With the ongoing Ottoman invasion, despite recognising the republic's invasion, as well as disunity between the Armenians, Azerbaijanis, and Georgians, it was impossible to keep it together. A speech by Irakli Tsereteli to the Sejm on May 26 confirmed the latter, in which he told the body that the republic from the start had been unable to operate due the people not being unified.[17] In response to this the Georgian leadership declared an independent state, the Democratic Republic of Georgia, on May 26, 1918.[18] This was followed two days later by both the Democratic Republic of Armenia and the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.[19]

Military

Following the Russian Revolution, the breakup of the Russian Caucasus Army left the Caucasus virtually undefended against the advancing Ottoman Third Army. In response, the Armenians, Georgians and Azerbaijanis attempted to establish a unified military, placing their forces under the command of a "Military Council of Nationalities". These forces consisted of Armenian volunteer units formed during the course of World War I; Georgian forces raised by their Provisional Government; and Azerbaijani troops raised independently.

The Military Council of Nationalities was short-lived. On May 28, 1918, Georgia signed the Treaty of Poti with Germany and welcomed the German Caucasus Expedition as protection against post-Revolution instability and the Ottoman military advance.[20] Azerbaijan, on the other hand, chose to ally itself with the Ottoman Empire.[21]

Government

Cabinet

| Portfolio | Minister |

|---|---|

| Prime Minister | Akaki Chkhenkeli |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Akaki Chkhenkeli |

| Minister of the Interior | Noe Ramishvili |

| Minister of Finance | Alexander Khatisian |

| Minister of Transportation | Khudadat bey Malik-Aslanov |

| Minister of Justice | Fatali Khan Khoyski |

| Minister of War | Grigol Giorgadze |

| Minister of Agriculture | Noe Khomeriki |

| Minister of Education | Nasib Yusifbeyli |

| Minister of Commerce and Industry | Mammad Hasan Hajinski |

| Minister of Supplies | Avetik Saakian |

| Minister of Social Welfare | Hovhannes Kajaznuni |

| Minister of Labour | Aramayis Erzinkian |

| Minister State Control | Ibrahim Haidarov |

Source:[22]

Legislature

- 32 Menshevik Social Democratic Labour Party members;

- 30 Musavat Party members;

- 17 Armenian Revolutionary Federation members, including Stepan Zorian ("Rosdom"), Hamo Ohanjanyan, H. Zavrian, Hovhannes Katchaznouni, S. Tigranian, Alexander Khatisian, K. Karchikian and M. Haroutiunian.

See also

- Transcaucasian SFSR

- Armenian–Azerbaijani War

- Georgian–Armenian War 1918

References

Notes

- Russian: Закавказская демократическая Федеративная Республика (ЗДФР), Zakavkazskaya Demokraticheskaya Federativnaya Respublika (ZDFR)

Citations

- Saparov 2015, p. 20

- Saparov 2015, pp. 21–23

- Marshall 2010, p. 38

- King 2008, p. 146

- King 2008, p. 150

- King 2008, p. 154

- Marshall 2010, pp. 48–49

- Suny 2015, p. 228

- de Waal 2015, p. 31

- King 2008, pp. 157–158

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 32–33

- Swietochowski 1985, pp. 84–85

- Suny 1994, p. 186

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 35

- Hovhannisian 1997, pp. 292–293

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 109

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 120

- Suny 1994, pp. 191–192

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 123–124

- Lang 1962, pp. 207–208

- Swietochowski 1985, p. 130

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 107

Bibliography

- de Waal, Thomas (2015), Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-935069-8

- Hovhannisian, Richard G. (2012), "Armenia's Road to Independence", in Hovhannisian, Richard G. (ed.), The Armenian People From Ancient Times to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: MacMillan, pp. 275–302, ISBN 0-333-61974-9

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1951), The Struggle for Transcaucasia (1917–1921), New York City: Philosophical Library, ISBN 978-0-95-600040-8

- King, Charles (2008), The Ghost of Freedom:A History of the Caucasus, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-539239-5

- Lang, David Marshall (1962), A Modern History of Soviet Georgia, New York City: Grove Press

- Marshall, Alex (2010), The Caucasus Under Soviet Rule, New York City: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-41-541012-0

- Saparov, Arsène (2015), From Conflict to Autonomy in the Caucasus: The Soviet Union and the making of Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno Karabakh, New York City: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-138-47615-8

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994), The Making of the Georgian Nation (Second ed.), Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-25-320915-3

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (2015), "They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else": A History of the Armenian Genocide, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-14730-7

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1985), Russian Azerbaijan, 1905–1920: The Shaping of National Identity in a Muslim Community, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521522-45-5

- Zürcher, Christoph (2007), The Post-Soviet Wars: Rebellion, Ethnic Conflict, and Nationhood in the Caucasus, New York City: New York University Press, ISBN 978-0-81-479709-9