Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic

Armenia (/ɑːrˈmiːniə/ (![]()

Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1920–1922 1936–1991 | |||||||||||||

Motto: Պրոլետարներ բոլոր երկրների, միացե՜ք (Armenian) Proletarner bolor erkrneri, miac’ek’ (transliteration) "Proletarians of all countries, unite!" | |||||||||||||

Anthem: Հայկական Սովետական Սոցիալիստական Հանրապետություն օրհներգ Haykakan Sovetakan Soc’ialistakan Hanrapetut’yun òrhnerg "Anthem of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic" (1944–1991) | |||||||||||||

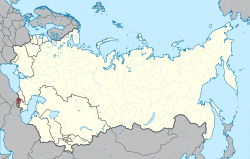

Location of Armenia (red) within the Soviet Union | |||||||||||||

| Status | Semi-independent state (1920–1922) Part of the Transcaucasian SFSR (1922–1936) Union republic (1936–1991) De facto sovereign entity (1990–1991) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Yerevan | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Official languages: Armenian · Russian Minority languages: Azerbaijani · Kurdish | ||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Armenian Soviet | ||||||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||||||

| Leader | |||||||||||||

• 1920–1921 | Gevork Alikhanyan (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1991 | Aram Gaspar Sargsyan (last) | ||||||||||||

| Head of state | |||||||||||||

• 1990–1991 | Levon Ter-Petrosyan (last) | ||||||||||||

| Premier | |||||||||||||

• 1921–1922 | Alexander Miasnikian (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1990–1991 | Vazgen Manukyan (last) | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Supreme Soviet | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Republic proclaimed | 2 December 1920 | ||||||||||||

• Becomes part of the Transcaucasian SFSR | 30 December 1922 | ||||||||||||

• Re-established | 5 December 1936 | ||||||||||||

| 20 February 1988 | |||||||||||||

• Sovereignty declared, Renamed Republic of Armenia | 23 August 1990 | ||||||||||||

• Independence declared | 21 September 1991 | ||||||||||||

• Independence completed | 26 December 1991 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1989 | 29,800 km2 (11,500 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1989 | 3,287,700 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Soviet ruble (руб) (SUR) | ||||||||||||

| Calling code | 7 885 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

As part of the Soviet Union, the Armenian SSR transformed from a largely agricultural hinterland to an important industrial production center, while its population almost quadrupled from around 880,000 in 1926 to 3.3 million in 1989 due to natural growth and large-scale influx of Armenian Genocide survivors and their descendants. On 23 August 1990, it was renamed the Republic of Armenia after its sovereignty was declared, but remained in the Soviet Union until its official proclamation of independence on 21 September 1991. Its independence was recognized on 26 December 1991 when the Soviet Union ceased to exist. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the state of the post-Soviet Republic of Armenia existed until the adoption of the new constitution in 1995.

History

Sovietization

Prior to Soviet rule, the Dashnaksutiun had governed the First Republic of Armenia. The Socialist Soviet Republic of Armenia was founded in 1920. Diaspora Armenians were divided about this: supporters of the nationalist Dashnaksutiun did not support the Soviet state, while supporters of the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) were more positive about the newly founded Soviet state.[2]

From 1828 with the Treaty of Turkmenchay to the October Revolution in 1917, Eastern Armenia had been part of the Russian Empire and partly confined to the borders of the Erivan Governorate. After the October Revolution, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin's government announced that minorities in the empire could pursue a course of self-determination. Following the collapse of the empire, in May 1918 Armenia, and its neighbors Azerbaijan and Georgia, declared their independence from Russian rule and each established their respective republics.[3] After the near-annihilation of the Armenians during the Armenian Genocide and the subsequent Turkish-Armenian War, the historic Armenian area in the Ottoman Empire was overrun with despair and devastation.

A number of Armenians joined the advancing 11th Soviet Red Army. Afterward, Turkey and the newly proclaimed Soviet republics in the Caucasus negotiated the Treaty of Kars, in which Turkey resigned from its claims to Batumi to Georgia in exchange for the Kars territory, corresponding to the modern-day Turkish provinces of Kars, Iğdır, and Ardahan. The medieval Armenian capital of Ani, as well as the cultural icon of the Armenian people Mount Ararat, were located in the ceded area. Additionally, Joseph Stalin, then acting Commissar for Nationalities, granted the areas of Nakhchivan and Nagorno-Karabakh (both of which were promised to Armenia by the Bolsheviks in 1920) to Azerbaijan.[4]

From 12 March 1922 to 5 December 1936, Armenia was a part of the Transcaucasian SFSR (TSFSR) together with the Georgian SSR and the Azerbaijan SSR. The policies of the first Soviet Armenian government, the Revolutionary Committee (Revkom), headed by young, inexperienced, and militant communists such as Sarkis Kasyan and Avis Nurijanyan, were implemented in a highhanded manner and did not take into consideration the poor conditions of the republic and the general weariness of the people after years of conflict and civil strife.[5] As the Soviet Armenian historian Bagrat Borian, who was to later perish during Stalin's purges, wrote in 1929:

The Revolutionary Committee started a series of indiscriminate seizures and confiscations, without regard to class, and without taking into account the general economic and psychological state of the peasantry. Devoid of revolutionary planning, and executed with needless brutality, these confiscations were unorganized and promiscuous. Unattended by disciplinary machinery, without preliminary propaganda or enlightenment, and with utter disregard of the country's unusually distressing condition, the Revolutionary Committee issued its orders nationalizing food supply of the cities and peasantry. With amazing recklessness and unconcern, they seized and nationalized everything – military uniforms, artisan tools, rice mills, water mills, barbers' implements, beehives, linen, household furniture, and livestock.[6]

Such was the degree and scale of the requisitioning and terror imposed by the local Cheka that in February 1921 the Armenians, led by former leaders of the republic, rose up in revolt and briefly unseated the communists in Yerevan. The Red Army, which was campaigning in Georgia at the time, returned to suppress the revolt and drove its leaders out of Armenia.[7]

Convinced that these heavy-handed tactics were the source of the alienation of the native population to Soviet rule, in 1921 Moscow appointed an experienced administrator, Alexander Miasnikian, to carry out a more moderate policy and one better attuned to Armenian sensibilities. With the introduction of the New Economic Policy (NEP), Armenians began to enjoy a period of relative stability. Life under the Soviet rule proved to be a soothing balm in contrast to the turbulent final years of the Ottoman Empire.[8] The Armenians received medicine, food, as well as other provisions from the central government and extensive literacy reforms were carried out.[9]

Stalin's Secretaryship

Stalin took several measures in persecuting the Armenian Church, already weakened by the Armenian Genocide and the Russification policies of the Russian Empire.[10] In the 1920s, the private property of the church was confiscated and priests were harassed. Soviet assaults against the Armenian Church accelerated under Stalin, beginning in 1929, but momentarily eased in the following years to improve the country's relations with the Armenian diaspora.[11] In 1932, Khoren Muradpekyan became known as Khoren I and assumed the title of His Holiness the Catholicos. However, in the late 1930s, the Soviets renewed their attacks against the Church.[12] This culminated in the murder of Khoren in 1938 as part of the Great Purge, and the closing of the Catholicosate of Echmiatsin on 4 August 1938. The Church, however, managed to survive underground and in the diaspora.[13]

The Great Purge was a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated against members of the Communist Party, writers and intellectuals, peasants and ordinary citizens. In September 1937 Stalin dispatched Anastas Mikoyan, along with Georgy Malenkov and Lavrentiy Beria, with a list of 300 names to Yerevan to oversee the liquidation of the Communist Party of Armenia (CPA), which was largely made up of Old Bolsheviks. Armenian communist leaders such as Vagharshak Ter-Vahanyan and Aghasi Khanjian fell victim to the purge, the former being a defendant at the first of the Moscow Show Trials. Mikoyan tried, but failed, to save one from being executed during his trip to Armenia. That person was arrested during one of his speeches to the CPA by Beria. Over a thousand people were arrested and seven of nine members of the Armenian Politburo were sacked from office.[14] According to one study, 4,530 people were executed by firing squad in the years 1937-38 alone, the majority of them having been accused of anti-Soviet or "counter-revolutionary" activities, for belonging to the nationalist Dashnak party, or Trotskyism.[15][16]

As with various other ethnic minorities who lived in the Soviet Union under Stalin, tens of thousands of Armenians were executed or deported. In 1936, Beria and Stalin worked to deport Armenians to Siberia in an attempt to bring Armenia's population under 700,000 in order to justify an annexation into Georgia.[13] Under Beria's command, police terror was used to strengthen the party's political hold on the population and suppress all expressions of nationalism. Many writers, artists, scientists and political leaders, including the writer Axel Bakunts and the celebrated poet Yeghishe Charents, were executed or forced into exile. Additionally, in 1944, roughly 200,000 Hamshenis (Armenians who live near the Black Sea coastal regions of Russia, Georgia and Turkey) were deported from Georgia to areas of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Further deportations of Armenians from the coastal region occurred in 1948, when 58,000 alleged supporters of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation and Greeks were forced to move to Kazakhstan.[17]

World War II

Armenia was spared the devastation and destruction that wrought most of the western Soviet Union during the Great Patriotic War of World War II. The Wehrmacht never reached the South Caucasus, which they intended to do in order to capture the oil fields in Azerbaijan. Still, Armenia played a valuable role in the war in providing food, manpower and war matériel. An estimated 300–500,000 Armenians served in the war, almost half of whom did not return.[18][19] Many attained the highest honor of Hero of the Soviet Union.[20] Over sixty Armenians were promoted to the rank of general, and with an additional four eventually achieving the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union: Ivan Bagramyan (the first non-Slavic commander to hold the position of front commander when he was assigned to be the commander of the First Baltic Front in 1943), Admiral Ivan Isakov, Hamazasp Babadzhanian, and Sergei Khudyakov.[20] The Soviet government, in an effort to shore up popular support for the war, also allowed for token expressions of nationalism with the re-publication of Armenian novels, the production of films such as David Bek (1944), and the easing of restrictions placed against the Church.[21] Stalin temporarily relented his attacks on religion during the war. This led to the election of bishop Gevork in 1945 as new Catholicos Gevork VI. He was subsequently allowed to reside in Echmiatsin.[22][23]

At the end of the war, after Germany's capitulation, many Armenians in both the Republic, including Armenian Communist Party First Secretary Grigor Harutyunyan (Arutyunov), and the diaspora lobbied Stalin to reconsider the issue of taking back the provinces of Kars, Iğdır, and Ardahan, which Armenia had lost to Turkey in the Treaty of Kars.[24] In September, 1945, the Soviet Union announced that it would annul the Soviet-Turkish treaty of friendship that was signed in 1925. Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov presented the claims put forth by the Armenians to the other Allied heads.

Turkey itself was in no condition to fight against the Soviet Union, which had emerged as a superpower after the war. By the autumn of 1945, Soviet troops in the Caucasus and Soviet-occupied Iran were already assembling for an invasion of Turkey. However, as the hostility between the East and West developed into the Cold War, especially after the issuing of the Truman Doctrine in 1947, Turkey strengthened its ties with the West. The Soviet Union relinquished its claims over the lost territories, understanding that the newly formed NATO would intervene on Turkey's side in the event of a conflict.[25]

Armenian immigration

.jpg)

With the republic suffering heavy losses after the war, Stalin allowed an open immigration policy in Armenia; the diaspora were invited to repatriate to Armenia (nergaght) and revitalize the country's population and bolster its workforce. Armenians living in countries such as Cyprus, France, Greece, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria were primarily the survivors or the descendants of the genocide. They were offered the option of having their expenses paid by the Soviet government for their trip back to their homeland. An estimated 150,000 Armenians immigrated to Soviet Armenia between 1946 and 1948 and settled in Yerevan, Leninakan, Kirovakan and other towns.[26][27]

Lured by numerous incentives such as food coupons, better housing and other benefits, they were received coldly by the Armenians living in the Republic upon their arrival. The repatriates spoke the Western Armenian dialect, instead of the Eastern Armenian spoken in Soviet Armenia. They were often addressed as aghbars ("brothers") by Armenians living in the republic, due to their different pronunciation of the word. Although initially used in humor, the word went on to carry on a more pejorative connotation.[28] Their treatment by the Soviet government was not much better. A number of Armenian immigrants in 1946 had their belongings confiscated upon arrival at Odessa's port, as they had taken with them everything they had, including clothes and jewelry. This was the first disappointment experienced by Armenians; however, as there was no possibility of return the Armenians were forced to continue their journey to Armenia. Many of the immigrants were targeted by Soviet intelligence agencies and the Ministry of Interior for real or perceived ties to Armenian nationalist organizations, and were later sent to labor camps in Siberia and elsewhere, where they would not be released until after Stalin's death. Some who were suspected of being dashnaks (Armenian nationalists) were targeted for deportation to Central Asia in 1949.[2]

Revival under Khrushchev

Following the power struggle after Stalin's death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev emerged as the country's new leader.[29] In a secret speech he gave in 1956, Khrushchev denounced Stalin and his domestic policies largely loosened the government's grip over the country. Khrushchev put more resources into the production of consumer goods and housing. Almost immediately, Armenia underwent a cultural and economic rebirth. Religious freedom, to a limited degree, was granted to Armenia when Catholicos Vazgen I assumed the duties of his office in 1955. One of Khrushchev's advisers and close friends, Armenian Politburo member Anastas Mikoyan, urged Armenians to reaffirm their national identity. In 1954, he gave a speech in Yerevan where he encouraged them to republish the works of writers such as Raffi and Charents.[30] The massive statue of Stalin that towered over Yerevan was pulled down from its pedestal by troops literally overnight and replaced in 1962 with that of Mother Armenia.[31] Contacts between Armenia and the Diaspora were revived, and Armenians from abroad began to visit the republic more frequently.

Many Armenians rose to prominence during this era, including one of Khrushchev's friends, Mikoyan, who was the older brother of the designer and co-founder of the Soviet MiG fighter jet company, Artem Mikoyan. Other famed Soviet Armenians included composer Aram Khachaturyan, who wrote the ballets Spartacus and Gayane that featured the well known "Sabre Dance," the noted astrophysicist and astronomer Viktor Hambardzumyan, and popular literary figures Paruyr Sevak, Sero Khanzadyan, Hovhannes Shiraz, and Silva Kaputikyan.

Brezhnev

_and_Ararat_Mountains).jpg)

After Leonid Brezhnev assumed power in 1964, much of Khrushchev's reforms were reversed. The Brezhnev era began a new state of stagnation, and saw a decline in both the quality and quantity of products in the Soviet Union. Armenia was severely affected by these policies, as was to be demonstrated several years later in the catastrophic earthquake that hit Spitak. Material allocated to the building of new homes, such as cement and concrete, was diverted for other uses. Bribery and a lack of oversight saw the construction of shoddily built and weakly supported apartment buildings. When the earthquake hit on the morning of 7 December 1988, the houses and apartments least able to resist collapse were those built during the Brezhnev years. Ironically, the older the dwellings, the better they withstood the quake.[32]

Though the Soviet state remained ever wary of the resurgence of Armenian nationalism, it did not impose the sort of restrictions as were seen during Stalin's time. On 24 April 1965, thousands of Armenians demonstrated in the streets of Yerevan during the fiftieth anniversary of the Armenian Genocide.[33]

The Gorbachev era

.jpg)

Mikhail Gorbachev's introduction of the policies of glasnost and perestroika in the 1980s also fueled Armenian visions of a better life under Soviet rule. The Hamshenis who were deported by Stalin to Kazakhstan began petitioning for the government to move them to the Armenian SSR. This move was denied by the Soviet government because of fears that the Muslim Hamshenis might spark ethnic conflicts with their Christian Armenian cousins.[17] However, another event that occurred during this time made an ethnic clash between Christian Armenians and Muslims inevitable.

Armenians in the region of Nagorno-Karabakh, which was promised to Armenia by the Bolsheviks but transferred to the Azerbaijan SSR by Stalin, began a movement to unite the area with Armenia. The majority Armenian population expressed concern about the forced "Azerification" of the region.[34] On February 20, 1988, the Supreme Soviet of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast voted to unify with Armenia.[35] Demonstrations took place in Yerevan showing support for the Karabakh Armenians. Azerbaijani authories encouraged counter demonstrations. However, these soon broke down into violence against Armenians in the city of Sumgait. Soon, ethnic rioting broke out between Armenians and Azeris, preventing a solid unification from taking place. A formal petition written to Gorbachev and senior leaders in Moscow asked for the unification of the enclave with Armenia, but the claim was rejected in the spring of 1988. Until then, the Soviet leader had been viewed favorably by Armenians, but following his refusal to alter his stance on the issue, Gorbachev's standing among Armenians deteriorated sharply.[36]

Independence

Tension between central and local government heightened in the final years of the Soviet Union's existence. On May 5, 1990, the New Armenian Army (NAA), a defense force envisioned to serve as a separate entity from the Soviet Union's military, was created. A celebration was planned for May 28, the anniversary of the creation of the first Armenian republic. However, on May 27 hostilities broke out between the NAA and the MVD troops based in Yerevan, resulting in the deaths of five Armenians in a shootout at the railway station. Witnesses claimed that the MVD had used an excessive amount of force in the firefight and insisted that it had instigated the fighting.[37] Further firefights between Armenian militiamen and the MVD in nearby Sovetashen (now Nubarashen) resulted in the deaths of twenty-seven people and an indefinite cancellation of the May 28 celebration.[38] Armenia declared its sovereignty over Soviet laws on August 23, 1990. The reason Armenia's decision to break away from the Soviet Union largely stemmed from Moscow's intransigence on Karabakh, mishandling of the earthquake relief effort, and the shortcomings of the Soviet economy.

On 17 March 1991, Armenia, along with the Baltics, Georgia and Moldova, boycotted a union-wide referendum in which 78% of all voters voted for the retention of the Soviet Union in a reformed form.[39]

Armenia declared its independence on 21 September 1991 after the unsuccessful coup attempt in Moscow by the CPSU hardliners. Greece became the first country to recognize the newly minted Armenian nation a few days later. Tensions between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh on the one hand and Azerbaijan on the other continued to escalate, ultimately leading to the outbreak of the Nagorno-Karabakh War. Despite a cease-fire in place since 1994, the parties have yet to resolve the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The Soviet Union itself ceased to exist on December 26, 1991 and Armenia became an sovereign independent state in the international stage. The United States recognized Armenia's independence a day before.

The country has seen substantial development since independence, moving away from a planned economy to a privatized one and adopting a representative democratic system of government. Armenia remains blockaded by both Turkey and Azerbaijan over the Karabakh dispute. It maintains friendly relations with its neighboring states of Georgia and Iran and is a strategic ally of Russia.

On 5 July 1995, the new constitution of Armenia was adopted.

Politics

Government

The structure of government in the Armenian SSR was identical to that of the other Soviet republics. The highest political body of the republic was the Armenian Supreme Soviet, which included the highest judicial branch of the republic, the supreme court. Members of the Supreme Soviet served for a term of five years, whereas regional deputies served for two and a half years. All officials holding office were mandated to be members of the Communist Party and sessions were convened in the Supreme Soviet building in Yerevan.

After independence and before the adoption of the 1995 Constitution, the Armenian Republic took place in a framework of a semi-presidential representative democratic republic with the President is the head of state and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and parliament. The unicameral parliament was the Supreme Council of Armenia.

With the establishment of the Republic, Soviet authorities worked tenaciously to eliminate certain elements in society, in whole or in part, such as nationalism and religion, to strengthen the cohesiveness of the Union. In the eyes of early Soviet policymakers, Armenians, along with Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Georgians, Germans, and Jews were deemed "advanced" (as opposed to "backward") peoples, and were grouped together with Western nationalities.[40] The Caucasus and particularly Armenia were recognized by academic scholars and in Soviet textbooks as the "oldest civilisation on the territory" of the Soviet Union.[41]

At first, Armenia was not affected significantly by the policies set forth by Lenin's government. Prior to his debilitating illness, Lenin encouraged the policy of Korenizatsiya or "nativization" in the republics which essentially called for the different nationalities of the Soviet Union to "administer their republics", establishing native-language schools, newspapers, and theaters.[42] In Armenia, the Soviet government ruled that all illiterate citizens up to the age of fifty to attend school and learn to read Armenian, which became the official language of the republic. The number of Armenian-language newspapers (Sovetakan Hayastan), magazines (Garun), and journals (Sovetakan Grakanutyun, Patma-Banasirakan Handes) grew. An institute for culture and history was created in 1921 in Echmiatsin, the Yerevan Opera Theater and a dramatic theater in Yerevan were built and established in the 1920s and 1930s, the Matenadaran, a facility to house ancient and medieval manuscripts was erected in 1959, important historical studies were prepared by a new cadre of Soviet-trained scholars, and popular works in the fields of art and literature were produced by such luminaries as Martiros Saryan, Avetik Isahakian and Yeghishe Charents, who all adhered to the socialist dictum of creating works "national in form, socialist in content." The first Armenian film studio, Armenkino, released the first fiction film, Namus (Honor) in 1925 and the first sound film Pepo, both directed by Hamo Bek-Nazarov.[43]

Like all the other republics of the Soviet Union, Armenia had its own flag and coat of arms. According to Nikita Khrushchev, the latter became a source of dispute between the Soviet Union and the Republic of Turkey in the 1950s, when Turkey objected to the inclusion of Mount Ararat, which holds a deep symbolic importance for Armenians but is located on Turkish territory, in the coat of arms. Turkey felt that the presence of such an image implied Soviet designs on Turkish territory. Khrushchev retorted by asking, "Why do you have a moon depicted on your flag? After all, the moon doesn't belong to Turkey, not even half the moon ... Do you want to take over the whole universe?"[44] Turkey dropped the issue after this.[45]

Participation in international organizations

Armenian SSR, as a Soviet republic, was internationally recognized by the United Nations as part of the Soviet Union but it had Norair Sisakian as President of the 21st session of the UNESCO General Conference in 1964. The Soviet Union was also a member of Comecon, Warsaw Pact and the International Olympic Committee.

Military forces

The military forces of the Armenian SSR were provided by the Soviet Army's 7th Guards Combined Arms Army of the Transcaucasian Military District. It was organized into the following:

- HQ of the 7th Guards Combined Arms Army - Yerevan[46]

- 15th Motor Rifle Division, Kirovakan[47]

- 127th Motor Rifle Division, Leninakan (today the Russian 102nd Military Base)

- 164th Motor Rifle Division, Yerevan

- 7th Fortified Area, Leninakan

- 9th Fortified Area, Echmiadzin

Economy

Under the Soviet system, the centralized economy of the republic banned private ownership of income producing property. Beginning in the late 1920s, privately owned farms in Armenia were collectivized and placed under the directive of the state, although this was often met with active resistance by the peasantry. During the same time (1929–1936), the government also began the process of industrialization in Armenia. By 1935, the gross product of agriculture was 132% of that of 1928 and the gross product of industry was 650% to that of 1928. The economic revolution of the 1930s, however, came at a great cost: it broke up the traditional peasant family and village institution and forced many living in the rural countryside to settle in urban areas. Private enterprise came to a virtual end as it was effectively brought under government control.[48]

Culture

Literature

Lazare Indjeyan's Les Années volées and Armand Maloumian's Les Fils du Goulag are two repatriate narratives about being incarcerated and eventual escape from gulags. Many other repatriate narratives explore family memories of the genocide and the decision to resettle in the Soviet Union. Some writers compare the 1949 Soviet deportations to Central Asia and Siberia with earlier Ottoman deportations.[2]

See also

Notes

- Standard pronunciation is in Eastern Armenian ([hɑjɑsˈtɑn]). Western Armenian: [hɑjɑsˈdɑn].

References

- "Armenia." Dictionary.com Unabridged. 2015.

- Jo Laycock (2016). "Survivor or Soviet Stories? Repatriate Narratives in Armenian Histories, Memories and Identities" (PDF). History and Memory. 28 (2): 123–151. doi:10.2979/histmemo.28.2.0123. ISSN 0935-560X. JSTOR 10.2979/histmemo.28.2.0123.

- The full history of the Armenian republic is covered by Richard G. Hovannisian, Republic of Armenia. 4 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971-1996.

- Matossian, Mary Kilbourne (1962). The Impact of Soviet Policies in Armenia. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8305-0081-9.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor. Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993, p. 139.

- Quoted in Ronald Grigor Suny. "Soviet Armenia," in The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, ed. Richard G. Hovannisian, New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997, p. 350.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. Republic of Armenia, Vol. IV: Between Crescent and Sickle, Partition and Sovietization. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996, pp. 405-07.

- Suny, "Soviet Armenia," pp. 355-57.

- Matossian. Impact of Soviet Policies, p. 80.

- Matossian. Impact of Soviet Policies, pp. 90-95, 147-151.

- Matossian. Impact of Soviet Policies, p. 150.

- Matossian. Impact of Soviet Policies, p. 194.

- Bauer-Manndorff, Elisabeth (1981). Armenia: Past and Present. New York: Armenian Prelacy, p. 178.

- Tucker, Robert (1992). Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1928-1941. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 488–489. ISBN 978-0-393-30869-3.

- Manoukian, A.S. "Հայաստանի հասարակական-քաղաքական գործիչները ստալինյան բռնությունների տարիներին [Armenian public-political figures in the years of Stalin's repression]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian) (1): 30.

- Kharatyan, Hranush (12 October 2014). Ռուսաստան-Մուստաֆա Քեմալ ծրագիրը. lragir.am (in Armenian).

- "Hamshenis denied return to Armenian SSR". Archived from the original on 2011-08-25. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- Walker, Christopher J. (1980). Armenia The Survival of a Nation, 2nd ed. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 355–356. ISBN 978-0-7099-0210-2.

- (in Armenian) Harutyunyan, Kliment. Հայ ժողովրդի մասնակցությունը Երկրորդ համաշխարհային պատերազմին (1939-1945 թթ.) [The Participation of the Armenian People in the Second World War, (1939-1945)] Yerevan: Hrazdan, 2001.

- (in Armenian) Khudaverdyan, Konstantine. «Սովետական Միության Հայրենական Մեծ Պատերազմ, 1941-1945» ("The Soviet Union's Great Patriotic War, 1941-1945"). Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1984, vol. 10, pp. 542-547.

- Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings And Priests to Merchants And Commissars. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 351. ISBN 978-0-231-13926-7.

- Matossian. Impact of Soviet Policies, pp. 194-195.

- Corley, Felix. "The Armenian Church under the Soviet Regime, Part 1: The Leadership of Kevork," Religion, State and Society 24 (1996): pp. 9-53.

- Dekmejian, R. Hrair, "The Armenian Diaspora," in The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, pp. 416-417.

- Krikorian, Robert O. "Kars-Ardahan and Soviet Armenian Irredentism, 1945-1946," in Armenian Kars and Ani, ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2011, pp. 393-410.

- Dekmejian. "The Armenian Diaspora", p. 416.

- Yousefian, Sevan, "The Postwar Repatriation Movement of Armenians to Soviet Armenia, 1945-1948," Unpublished Ph.D Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 2011.

- Bournoutian, George A. (2006). A Concise History of the Armenian People. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishing, p. 324. ISBN 1-56859-141-1.

- On the transition from Stalin to Khrushchev as it affected Armenia, consult (in Armenian) Amatuni Virabyan, Հայաստանը Ստալինից մինչև Խրուշչով: Հասարակական-քաղաքական կյանքը 1945-1957 թթ. [Armenia from Stalin to Khrushchev: Social-political life, 1945-57] Yerevan: Gitutyun Publishing, 2001.

- Matossian. Impact of Soviet Policies, p. 201.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1983). Armenia in the Twentieth Century. Chico, CA: Scholars Press, pp. 72-73.

- Verluise, Pierre and Levon Chorbajian (1995). Armenia in Crisis: the 1988 Earthquake. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Bobelian, Michael (2009). Children of Armenia: A Forgotten Genocide and the Century-long Struggle for Justice. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 121ff. ISBN 978-1-4165-5725-8.

- On Karabakh, see Cheterian, Vicken (2009). War and Peace in the Caucasus: Russia's Troubled Frontier. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 87–154. ISBN 978-0-231-70064-1.

- Kaufman, Stuart (2001). Modern Hatreds: The Symbolic Politics of Ethnic War. New York: Cornell Studies in Security Affairs. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8014-8736-1.

- See Thomas de Waal, Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through War and Peace. New York: New York University Press, 2013.

- Krikorian, Robert O and Joseph R. Masih. Armenia: At the Crossroads. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1999, pp. 19-20.

- (in Armenian) "1990 թվականի այս օրը խորհրդային բանակը մտավ Երևան" [The Soviet Army entered Yerevan on this day in May 1990]. Ilur.am. May 27, 2013.

- "Baltic states, Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova boycott USSR referendum". Archived from the original on November 16, 2005. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- Martin, Terry (2001). The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. New York: Cornell University, p. 23. ISBN 0-8014-8677-7.

- Panossian. The Armenians, pp. 288-89.

- Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire, pp. 10-13.

- Suny, "Soviet Armenia," pp. 356-57.

- Khrushchev, Nikita, Sergei Khrushchev (ed.) Memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev: Statesman, 1953-1964. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp. 467-68. ISBN 0-271-02935-8.

- Khrushchev. Memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev, p. 468.

- Holm, Michael. "7th Guards Combined Arms Army". www.ww2.dk. Retrieved 2016-02-14.

- Holm, Michael. "91st Motorised Rifle Division". www.ww2.dk. Retrieved 2016-02-14.

- Matossian. Impact of Soviet Policies, pp. 99-116.

Further reading

- (in Armenian) Aghayan, Tsatur., et al. (eds.), Հայ Ժողովրդի Պատմություն [History of the Armenian People], vols. 7 and 8. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1967, 1970.

- (in Armenian) Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1974–1987, 12 volumes.

- Aslanyan, A. A. et al. Soviet Armenia. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1971.

- (in Armenian) Geghamyan, Gurgen M. Սոցիալ-տնտեսական փոփոխությունները Հայաստանում ՆԵՊ-ի տարիներին (1921-1936) [Socio-Economic Changes in the Armenia during the NEP Years, (1921-1936)]. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1978.

- Matossian, Mary Kilbourne. The Impact of Soviet Policies in Armenia. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1962.

- Miller, Donald E. and Lorna Touryan Miller, Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

- Shaginian [Shahinyan], Marietta S. Journey through Soviet Armenia. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1954.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor. "Soviet Armenia," in The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, ed. Richard G. Hovannisian, New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997.

- (in Armenian) Virabyan, Amatuni. Հայաստանը Ստալինից մինչև Խրուշչով: Հասարակական-քաղաքական կյանքը 1945-1957 թթ. [Armenia from Stalin to Khrushchev: Social-political life, 1945-1957] Yerevan: Gitutyun Publishing, 2001.

- Walker, Christopher J. Armenia: The Survival of a Nation. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1990.

- Yeghenian, Aghavnie Y. The Red Flag at Ararat. New York: The Womans Press, 1932. Republished by the Gomidas Institute in London, 2013.

External links

| Look up armenian soviet socialist republic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Armenia: big strides in an ancient land by Anton Kochinyan

- Melkonian, Eduard: "Repressions in 1930s Soviet Armenia" in the Caucasus Analytical digest No. 22

.svg.png)