Sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sculptural processes originally used carving (the removal of material) and modelling (the addition of material, as clay), in stone, metal, ceramics, wood and other materials but, since Modernism, there has been an almost complete freedom of materials and process. A wide variety of materials may be worked by removal such as carving, assembled by welding or modelling, or moulded or cast.

Sculpture in stone survives far better than works of art in perishable materials, and often represents the majority of the surviving works (other than pottery) from ancient cultures, though conversely traditions of sculpture in wood may have vanished almost entirely. However, most ancient sculpture was brightly painted, and this has been lost.[2]

Sculpture has been central in religious devotion in many cultures, and until recent centuries large sculptures, too expensive for private individuals to create, were usually an expression of religion or politics. Those cultures whose sculptures have survived in quantities include the cultures of the ancient Mediterranean, India and China, as well as many in Central and South America and Africa.

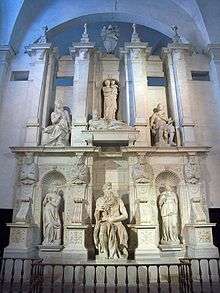

The Western tradition of sculpture began in ancient Greece, and Greece is widely seen as producing great masterpieces in the classical period. During the Middle Ages, Gothic sculpture represented the agonies and passions of the Christian faith. The revival of classical models in the Renaissance produced famous sculptures such as Michelangelo's David. Modernist sculpture moved away from traditional processes and the emphasis on the depiction of the human body, with the making of constructed sculpture, and the presentation of found objects as finished art works.

Types

A basic distinction is between sculpture in the round, free-standing sculpture, such as statues, not attached (except possibly at the base) to any other surface, and the various types of relief, which are at least partly attached to a background surface. Relief is often classified by the degree of projection from the wall into low or bas-relief, high relief, and sometimes an intermediate mid-relief. Sunk-relief is a technique restricted to ancient Egypt. Relief is the usual sculptural medium for large figure groups and narrative subjects, which are difficult to accomplish in the round, and is the typical technique used both for architectural sculpture, which is attached to buildings, and for small-scale sculpture decorating other objects, as in much pottery, metalwork and jewellery. Relief sculpture may also decorate steles, upright slabs, usually of stone, often also containing inscriptions.

Another basic distinction is between subtractive carving techniques, which remove material from an existing block or lump, for example of stone or wood, and modelling techniques which shape or build up the work from the material. Techniques such as casting, stamping and moulding use an intermediate matrix containing the design to produce the work; many of these allow the production of several copies.

The term "sculpture" is often used mainly to describe large works, which are sometimes called monumental sculpture, meaning either or both of sculpture that is large, or that is attached to a building. But the term properly covers many types of small works in three dimensions using the same techniques, including coins and medals, hardstone carvings, a term for small carvings in stone that can take detailed work.

The very large or "colossal" statue has had an enduring appeal since antiquity; the largest on record at 182 m (597 ft) is the 2018 Indian Statue of Unity. Another grand form of portrait sculpture is the equestrian statue of a rider on horse, which has become rare in recent decades. The smallest forms of life-size portrait sculpture are the "head", showing just that, or the bust, a representation of a person from the chest up. Small forms of sculpture include the figurine, normally a statue that is no more than 18 inches (46 cm) tall, and for reliefs the plaquette, medal or coin.

Modern and contemporary art have added a number of non-traditional forms of sculpture, including sound sculpture, light sculpture, environmental art, environmental sculpture, street art sculpture, kinetic sculpture (involving aspects of physical motion), land art, and site-specific art. Sculpture is an important form of public art. A collection of sculpture in a garden setting can be called a sculpture garden.

Purposes and subjects

One of the most common purposes of sculpture is in some form of association with religion. Cult images are common in many cultures, though they are often not the colossal statues of deities which characterized ancient Greek art, like the Statue of Zeus at Olympia. The actual cult images in the innermost sanctuaries of Egyptian temples, of which none have survived, were evidently rather small, even in the largest temples. The same is often true in Hinduism, where the very simple and ancient form of the lingam is the most common. Buddhism brought the sculpture of religious figures to East Asia, where there seems to have been no earlier equivalent tradition, though again simple shapes like the bi and cong probably had religious significance.

Small sculptures as personal possessions go back to the earliest prehistoric art, and the use of very large sculpture as public art, especially to impress the viewer with the power of a ruler, goes back at least to the Great Sphinx of some 4,500 years ago. In archaeology and art history the appearance, and sometimes disappearance, of large or monumental sculpture in a culture is regarded as of great significance, though tracing the emergence is often complicated by the presumed existence of sculpture in wood and other perishable materials of which no record remains;[3]

The totem pole is an example of a tradition of monumental sculpture in wood that would leave no traces for archaeology. The ability to summon the resources to create monumental sculpture, by transporting usually very heavy materials and arranging for the payment of what are usually regarded as full-time sculptors, is considered a mark of a relatively advanced culture in terms of social organization. Recent unexpected discoveries of ancient Chinese Bronze Age figures at Sanxingdui, some more than twice human size, have disturbed many ideas held about early Chinese civilization, since only much smaller bronzes were previously known.[4]

Some undoubtedly advanced cultures, such as the Indus Valley civilization, appear to have had no monumental sculpture at all, though producing very sophisticated figurines and seals. The Mississippian culture seems to have been progressing towards its use, with small stone figures, when it collapsed. Other cultures, such as ancient Egypt and the Easter Island culture, seem to have devoted enormous resources to very large-scale monumental sculpture from a very early stage.

The collecting of sculpture, including that of earlier periods, goes back some 2,000 years in Greece, China and Mesoamerica, and many collections were available on semi-public display long before the modern museum was invented. From the 20th century the relatively restricted range of subjects found in large sculpture expanded greatly, with abstract subjects and the use or representation of any type of subject now common. Today much sculpture is made for intermittent display in galleries and museums, and the ability to transport and store the increasingly large works is a factor in their construction. Small decorative figurines, most often in ceramics, are as popular today (though strangely neglected by modern and Contemporary art) as they were in the Rococo, or in ancient Greece when Tanagra figurines were a major industry, or in East Asian and Pre-Columbian art. Small sculpted fittings for furniture and other objects go well back into antiquity, as in the Nimrud ivories, Begram ivories and finds from the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Portrait sculpture began in Egypt, where the Narmer Palette shows a ruler of the 32nd century BCE, and Mesopotamia, where we have 27 surviving statues of Gudea, who ruled Lagash c. 2144–2124 BCE. In ancient Greece and Rome, the erection of a portrait statue in a public place was almost the highest mark of honour, and the ambition of the elite, who might also be depicted on a coin.[5] In other cultures such as Egypt and the Near East public statues were almost exclusively the preserve of the ruler, with other wealthy people only being portrayed in their tombs. Rulers are typically the only people given portraits in Pre-Columbian cultures, beginning with the Olmec colossal heads of about 3,000 years ago. East Asian portrait sculpture was entirely religious, with leading clergy being commemorated with statues, especially the founders of monasteries, but not rulers, or ancestors. The Mediterranean tradition revived, initially only for tomb effigies and coins, in the Middle Ages, but expanded greatly in the Renaissance, which invented new forms such as the personal portrait medal.

Animals are, with the human figure, the earliest subject for sculpture, and have always been popular, sometimes realistic, but often imaginary monsters; in China animals and monsters are almost the only traditional subjects for stone sculpture outside tombs and temples. The kingdom of plants is important only in jewellery and decorative reliefs, but these form almost all the large sculpture of Byzantine art and Islamic art, and are very important in most Eurasian traditions, where motifs such as the palmette and vine scroll have passed east and west for over two millennia.

One form of sculpture found in many prehistoric cultures around the world is specially enlarged versions of ordinary tools, weapons or vessels created in impractical precious materials, for either some form of ceremonial use or display or as offerings. Jade or other types of greenstone were used in China, Olmec Mexico, and Neolithic Europe, and in early Mesopotamia large pottery shapes were produced in stone. Bronze was used in Europe and China for large axes and blades, like the Oxborough Dirk.

Materials and techniques

The materials used in sculpture are diverse, changing throughout history. The classic materials, with outstanding durability, are metal, especially bronze, stone and pottery, with wood, bone and antler less durable but cheaper options. Precious materials such as gold, silver, jade, and ivory are often used for small luxury works, and sometimes in larger ones, as in chryselephantine statues. More common and less expensive materials were used for sculpture for wider consumption, including hardwoods (such as oak, box/boxwood, and lime/linden); terracotta and other ceramics, wax (a very common material for models for casting, and receiving the impressions of cylinder seals and engraved gems), and cast metals such as pewter and zinc (spelter). But a vast number of other materials have been used as part of sculptures, in ethnographic and ancient works as much as modern ones.

Sculptures are often painted, but commonly lose their paint to time, or restorers. Many different painting techniques have been used in making sculpture, including tempera, oil painting, gilding, house paint, aerosol, enamel and sandblasting.[2][6]

Many sculptors seek new ways and materials to make art. One of Pablo Picasso's most famous sculptures included bicycle parts. Alexander Calder and other modernists made spectacular use of painted steel. Since the 1960s, acrylics and other plastics have been used as well. Andy Goldsworthy makes his unusually ephemeral sculptures from almost entirely natural materials in natural settings. Some sculpture, such as ice sculpture, sand sculpture, and gas sculpture, is deliberately short-lived. Recent sculptors have used stained glass, tools, machine parts, hardware and consumer packaging to fashion their works. Sculptors sometimes use found objects, and Chinese scholar's rocks have been appreciated for many centuries.

Stone

Stone sculpture is an ancient activity where pieces of rough natural stone are shaped by the controlled removal of stone. Owing to the permanence of the material, evidence can be found that even the earliest societies indulged in some form of stone work, though not all areas of the world have such abundance of good stone for carving as Egypt, Greece, India and most of Europe. Petroglyphs (also called rock engravings) are perhaps the earliest form: images created by removing part of a rock surface which remains in situ, by incising, pecking, carving, and abrading. Monumental sculpture covers large works, and architectural sculpture, which is attached to buildings. Hardstone carving is the carving for artistic purposes of semi-precious stones such as jade, agate, onyx, rock crystal, sard or carnelian, and a general term for an object made in this way. Alabaster or mineral gypsum is a soft mineral that is easy to carve for smaller works and still relatively durable. Engraved gems are small carved gems, including cameos, originally used as seal rings.

The copying of an original statue in stone, which was very important for ancient Greek statues, which are nearly all known from copies, was traditionally achieved by "pointing", along with more freehand methods. Pointing involved setting up a grid of string squares on a wooden frame surrounding the original, and then measuring the position on the grid and the distance between grid and statue of a series of individual points, and then using this information to carve into the block from which the copy is made.[8]

Metal

Bronze and related copper alloys are the oldest and still the most popular metals for cast metal sculptures; a cast bronze sculpture is often called simply a "bronze". Common bronze alloys have the unusual and desirable property of expanding slightly just before they set, thus filling the finest details of a mould. Their strength and lack of brittleness (ductility) is an advantage when figures in action are to be created, especially when compared to various ceramic or stone materials (see marble sculpture for several examples). Gold is the softest and most precious metal, and very important in jewellery; with silver it is soft enough to be worked with hammers and other tools as well as cast; repoussé and chasing are among the techniques used in gold and silversmithing.

Casting is a group of manufacturing processes by which a liquid material (bronze, copper, glass, aluminum, iron) is (usually) poured into a mould, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solid casting is then ejected or broken out to complete the process,[9] although a final stage of "cold work" may follow on the finished cast. Casting may be used to form hot liquid metals or various materials that cold set after mixing of components (such as epoxies, concrete, plaster and clay). Casting is most often used for making complex shapes that would be otherwise difficult or uneconomical to make by other methods. The oldest surviving casting is a copper Mesopotamian frog from 3200 BCE.[10] Specific techniques include lost-wax casting, plaster mould casting and sand casting.

Welding is a process where different pieces of metal are fused together to create different shapes and designs. There are many different forms of welding, such as Oxy-fuel welding, Stick welding, MIG welding, and TIG welding. Oxy-fuel is probably the most common method of welding when it comes to creating steel sculptures because it is the easiest to use for shaping the steel as well as making clean and less noticeable joins of the steel. The key to Oxy-fuel welding is heating each piece of metal to be joined evenly until all are red and have a shine to them. Once that shine is on each piece, that shine will soon become a 'pool' where the metal is liquified and the welder must get the pools to join together, fusing the metal. Once cooled off, the location where the pools joined are now one continuous piece of metal. Also used heavily in Oxy-fuel sculpture creation is forging. Forging is the process of heating metal to a certain point to soften it enough to be shaped into different forms. One very common example is heating the end of a steel rod and hitting the red heated tip with a hammer while on an anvil to form a point. In between hammer swings, the forger rotates the rod and gradually forms a sharpened point from the blunt end of a steel rod.

Glass

Glass may be used for sculpture through a wide range of working techniques, though the use of it for large works is a recent development. It can be carved, with considerable difficulty; the Roman Lycurgus Cup is all but unique.[11] Hot casting can be done by ladling molten glass into moulds that have been created by pressing shapes into sand, carved graphite or detailed plaster/silica moulds. Kiln casting glass involves heating chunks of glass in a kiln until they are liquid and flow into a waiting mould below it in the kiln. Glass can also be blown and/or hot sculpted with hand tools either as a solid mass or as part of a blown object. More recent techniques involve chiseling and bonding plate glass with polymer silicates and UV light.[12]

Pottery

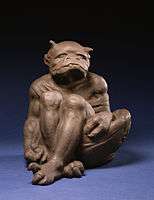

Pottery is one of the oldest materials for sculpture, as well as clay being the medium in which many sculptures cast in metal are originally modelled for casting. Sculptors often build small preliminary works called maquettes of ephemeral materials such as plaster of Paris, wax, unfired clay, or plasticine.[13] Many cultures have produced pottery which combines a function as a vessel with a sculptural form, and small figurines have often been as popular as they are in modern Western culture. Stamps and moulds were used by most ancient civilizations, from ancient Rome and Mesopotamia to China.[14]

Wood carving

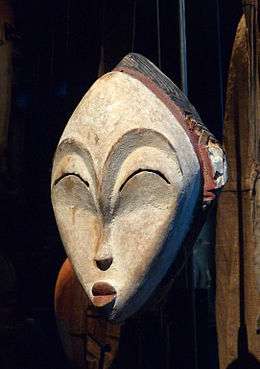

Wood carving has been extremely widely practiced, but survives much less well than the other main materials, being vulnerable to decay, insect damage, and fire. It therefore forms an important hidden element in the art history of many cultures.[3] Outdoor wood sculpture does not last long in most parts of the world, so that we have little idea how the totem pole tradition developed. Many of the most important sculptures of China and Japan in particular are in wood, and the great majority of African sculpture and that of Oceania and other regions.

Wood is light, so suitable for masks and other sculpture intended to be carried, and can take very fine detail. It is also much easier to work than stone. It has been very often painted after carving, but the paint wears less well than the wood, and is often missing in surviving pieces. Painted wood is often technically described as "wood and polychrome". Typically a layer of gesso or plaster is applied to the wood, and then the paint is applied to that.

Social status of sculptors

Worldwide, sculptors have usually been tradesmen whose work is unsigned; in some traditions, for example China, where sculpture did not share the prestige of literati painting, this has affected the status of sculpture itself.[15] Even in ancient Greece, where sculptors such as Phidias became famous, they appear to have retained much the same social status as other artisans, and perhaps not much greater financial rewards, although some signed their works.[16] In the Middle Ages artists such as the 12th-century Gislebertus sometimes signed their work, and were sought after by different cities, especially from the Trecento onwards in Italy, with figures such as Arnolfo di Cambio, and Nicola Pisano and his son Giovanni. Goldsmiths and jewellers, dealing with precious materials and often doubling as bankers, belonged to powerful guilds and had considerable status, often holding civic office. Many sculptors also practised in other arts; Andrea del Verrocchio also painted, and Giovanni Pisano, Michelangelo, and Jacopo Sansovino were architects. Some sculptors maintained large workshops. Even in the Renaissance the physical nature of the work was perceived by Leonardo da Vinci and others as pulling down the status of sculpture in the arts, though the reputation of Michelangelo perhaps put this long-held idea to rest.

From the High Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo, Leone Leoni and Giambologna could become wealthy, and ennobled, and enter the circle of princes, after a period of sharp argument over the relative status of sculpture and painting.[17] Much decorative sculpture on buildings remained a trade, but sculptors producing individual pieces were recognised on a level with painters. From the 18th century or earlier sculpture also attracted middle-class students, although it was slower to do so than painting. Women sculptors took longer to appear than women painters, and were less prominent until the 20th century.

Anti-sculpture movements

Aniconism remained restricted to Judaism, which did not accept figurative sculpture until the 19th century,[18] before expanding to Early Christianity, which initially accepted large sculptures. In Christianity and Buddhism, sculpture became very significant. Christian Eastern Orthodoxy has never accepted monumental sculpture, and Islam has consistently rejected nearly all figurative sculpture, except for very small figures in reliefs and some animal figures that fulfill a useful function, like the famous lions supporting a fountain in the Alhambra. Many forms of Protestantism also do not approve of religious sculpture. There has been much iconoclasm of sculpture from religious motives, from the Early Christians, the Beeldenstorm of the Protestant Reformation to the 2001 destruction of the Buddhas of Bamyan by the Taliban.

History

Prehistoric periods

Europe

The earliest undisputed examples of sculpture belong to the Aurignacian culture, which was located in Europe and southwest Asia and active at the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic. As well as producing some of the earliest known cave art, the people of this culture developed finely-crafted stone tools, manufacturing pendants, bracelets, ivory beads, and bone-flutes, as well as three-dimensional figurines.[19][20]

The 30 cm tall Löwenmensch found in the Hohlenstein Stadel area of Germany is an anthropomorphic lion-man figure carved from woolly mammoth ivory. It has been dated to about 35–40,000 BP, making it, along with the Venus of Hohle Fels, the oldest known uncontested example of figurative art.[21]

Much surviving prehistoric art is small portable sculptures, with a small group of female Venus figurines such as the Venus of Willendorf (24–26,000 BP) found across central Europe.[22] The Swimming Reindeer of about 13,000 years ago is one of the finest of a number of Magdalenian carvings in bone or antler of animals in the art of the Upper Paleolithic, although they are outnumbered by engraved pieces, which are sometimes classified as sculpture.[23] Two of the largest prehistoric sculptures can be found at the Tuc d'Audobert caves in France, where around 12–17,000 years ago a masterful sculptor used a spatula-like stone tool and fingers to model a pair of large bison in clay against a limestone rock.[24]

With the beginning of the Mesolithic in Europe figurative sculpture greatly reduced,[25] and remained a less common element in art than relief decoration of practical objects until the Roman period, despite some works such as the Gundestrup cauldron from the European Iron Age and the Bronze Age Trundholm sun chariot.[26]

Ancient Near East

From the ancient Near East, the over-life sized stone Urfa Man from modern Turkey comes from about 9,000 BCE, and the 'Ain Ghazal Statues from around 7200 and 6500 BCE. These are from modern Jordan, made of lime plaster and reeds, and about half life-size; there are 15 statues, some with two heads side by side, and 15 busts. Small clay figures of people and animals are found at many sites across the Near East from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, and represent the start of a more-or-less continuous tradition in the region.

Löwenmensch, from Hohlenstein-Stadel, now in Ulmer Museum, Ulm, Germany, the oldest known anthropomorphic animal-human statuette, Aurignacian era, c. 35–40,000 BP

Löwenmensch, from Hohlenstein-Stadel, now in Ulmer Museum, Ulm, Germany, the oldest known anthropomorphic animal-human statuette, Aurignacian era, c. 35–40,000 BP

Swimming Reindeer c. 13,000 BP, female and male swimming reindeer – late Magdalenian period, found at Montastruc, Tarn et Garonne, France

Swimming Reindeer c. 13,000 BP, female and male swimming reindeer – late Magdalenian period, found at Montastruc, Tarn et Garonne, France Urfa Man, in the Şanlıurfa Museum; sandstone, 1.80 meters, c. 9,000 BCE

Urfa Man, in the Şanlıurfa Museum; sandstone, 1.80 meters, c. 9,000 BCE- A Jōmon dogū figure, 1st millennium BCE, Japan

The Trundholm sun chariot, perhaps 1800–1500 BCE; this side is gilded, the other is "dark".

The Trundholm sun chariot, perhaps 1800–1500 BCE; this side is gilded, the other is "dark".

Ancient Near East

The Protoliterate period in Mesopotamia, dominated by Uruk, saw the production of sophisticated works like the Warka Vase and cylinder seals. The Guennol Lioness is an outstanding small limestone figure from Elam of about 3000–2800 BCE, part human and part lioness.[27] A little later there are a number of figures of large-eyed priests and worshippers, mostly in alabaster and up to a foot high, who attended temple cult images of the deity, but very few of these have survived.[28] Sculptures from the Sumerian and Akkadian period generally had large, staring eyes, and long beards on the men. Many masterpieces have also been found at the Royal Cemetery at Ur (c. 2650 BCE), including the two figures of a Ram in a Thicket, the Copper Bull and a bull's head on one of the Lyres of Ur.[29]

From the many subsequent periods before the ascendency of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 10th century BCE Mesopotamian art survives in a number of forms: cylinder seals, relatively small figures in the round, and reliefs of various sizes, including cheap plaques of moulded pottery for the home, some religious and some apparently not.[30] The Burney Relief is an unusually elaborate and relatively large (20 x 15 inches, 50 x 37 cm) terracotta plaque of a naked winged goddess with the feet of a bird of prey, and attendant owls and lions. It comes from the 18th or 19th centuries BCE, and may also be moulded.[31] Stone stelae, votive offerings, or ones probably commemorating victories and showing feasts, are also found from temples, which unlike more official ones lack inscriptions that would explain them;[32] the fragmentary Stele of the Vultures is an early example of the inscribed type,[33] and the Assyrian Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III a large and solid late one.[34]

The conquest of the whole of Mesopotamia and much surrounding territory by the Assyrians created a larger and wealthier state than the region had known before, and very grandiose art in palaces and public places, no doubt partly intended to match the splendour of the art of the neighbouring Egyptian empire. Unlike earlier states, the Assyrians could use easily carved stone from northern Iraq, and did so in great quantity. The Assyrians developed a style of extremely large schemes of very finely detailed narrative low reliefs in stone for palaces, with scenes of war or hunting; the British Museum has an outstanding collection, including the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal and the Lachish reliefs showing a campaign. They produced very little sculpture in the round, except for colossal guardian figures of the human-headed lamassu, which are sculpted in high relief on two sides of a rectangular block, with the heads effectively in the round (and also five legs, so that both views seem complete). Even before dominating the region they had continued the cylinder seal tradition with designs which are often exceptionally energetic and refined.[35]

One of 18 Statues of Gudea, a ruler around 2090 BCE

One of 18 Statues of Gudea, a ruler around 2090 BCE- The Burney Relief, Old Babylonian, around 1800 BCE

%2C_c._645-635_BC%2C_British_Museum_(16722368932).jpg) Part of the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal, c. 640 BCE, Nineveh

Part of the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal, c. 640 BCE, Nineveh

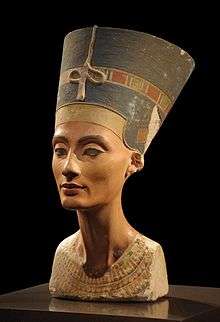

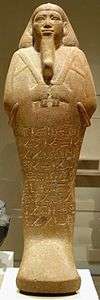

Ancient Egypt

The monumental sculpture of ancient Egypt is world-famous, but refined and delicate small works exist in much greater numbers. The Egyptians used the distinctive technique of sunk relief, which is well suited to very bright sunlight. The main figures in reliefs adhere to the same figure convention as in painting, with parted legs (where not seated) and head shown from the side, but the torso from the front, and a standard set of proportions making up the figure, using 18 "fists" to go from the ground to the hair-line on the forehead.[36] This appears as early as the Narmer Palette from Dynasty I. However, there as elsewhere the convention is not used for minor figures shown engaged in some activity, such as the captives and corpses.[37] Other conventions make statues of males darker than females ones. Very conventionalized portrait statues appear from as early as Dynasty II, before 2,780 BCE,[38] and with the exception of the art of the Amarna period of Ahkenaten,[39] and some other periods such as Dynasty XII, the idealized features of rulers, like other Egyptian artistic conventions, changed little until after the Greek conquest.[40]

Egyptian pharaohs were always regarded as deities, but other deities are much less common in large statues, except when they represent the pharaoh as another deity; however the other deities are frequently shown in paintings and reliefs. The famous row of four colossal statues outside the main temple at Abu Simbel each show Rameses II, a typical scheme, though here exceptionally large.[41] Small figures of deities, or their animal personifications, are very common, and found in popular materials such as pottery. Most larger sculpture survives from Egyptian temples or tombs; by Dynasty IV (2680–2565 BCE) at the latest the idea of the Ka statue was firmly established. These were put in tombs as a resting place for the ka portion of the soul, and so we have a good number of less conventionalized statues of well-off administrators and their wives, many in wood as Egypt is one of the few places in the world where the climate allows wood to survive over millennia. The so-called reserve heads, plain hairless heads, are especially naturalistic. Early tombs also contained small models of the slaves, animals, buildings and objects such as boats necessary for the deceased to continue his lifestyle in the afterworld, and later Ushabti figures.[42]

- Facsimile of the Narmer Palette, c. 3100 BCE, which already shows the canonical Egyptian profile view and proportions of the figure

_and_queen.jpg) Menkaura (Mycerinus) and queen, Old Kingdom, Dynasty 4, 2490–2472 BCE. The formality of the pose is reduced by the queen's arm round her husband

Menkaura (Mycerinus) and queen, Old Kingdom, Dynasty 4, 2490–2472 BCE. The formality of the pose is reduced by the queen's arm round her husband- Wooden tomb models, Dynasty XI; a high administrator counts his cattle

Tutankhamun's mask, c. late Eighteenth dynasty, Egyptian Museum

Tutankhamun's mask, c. late Eighteenth dynasty, Egyptian Museum_(Room_4).jpg) The Younger Memnon c. 1250 BCE, British Museum

The Younger Memnon c. 1250 BCE, British Museum Osiris on a lapis lazuli pillar in the middle, flanked by Horus on the left, and Isis on the right, 22nd dynasty, Louvre

Osiris on a lapis lazuli pillar in the middle, flanked by Horus on the left, and Isis on the right, 22nd dynasty, Louvre The ka statue provided a physical place for the ka to manifest. Egyptian Museum, Cairo

The ka statue provided a physical place for the ka to manifest. Egyptian Museum, Cairo Block statue of Pa-Ankh-Ra, ship master, bearing a statue of Ptah. Late Period, c. 650–633 BCE, Cabinet des Médailles

Block statue of Pa-Ankh-Ra, ship master, bearing a statue of Ptah. Late Period, c. 650–633 BCE, Cabinet des Médailles

Europe

Ancient Greece

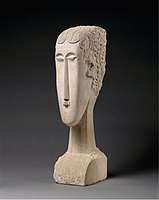

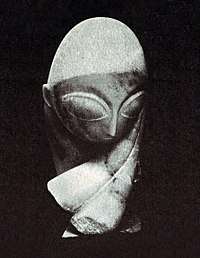

The first distinctive style of ancient Greek sculpture developed in the Early Bronze Age Cycladic period (3rd millennium BCE), where marble figures, usually female and small, are represented in an elegantly simplified geometrical style. Most typical is a standing pose with arms crossed in front, but other figures are shown in different poses, including a complicated figure of a harpist seated on a chair.[43]

The subsequent Minoan and Mycenaean cultures developed sculpture further, under influence from Syria and elsewhere, but it is in the later Archaic period from around 650 BCE that the kouros developed. These are large standing statues of naked youths, found in temples and tombs, with the kore as the clothed female equivalent, with elaborately dressed hair; both have the "archaic smile". They seem to have served a number of functions, perhaps sometimes representing deities and sometimes the person buried in a grave, as with the Kroisos Kouros. They are clearly influenced by Egyptian and Syrian styles, but the Greek artists were much more ready to experiment within the style.

During the 6th century Greek sculpture developed rapidly, becoming more naturalistic, and with much more active and varied figure poses in narrative scenes, though still within idealized conventions. Sculptured pediments were added to temples, including the Parthenon in Athens, where the remains of the pediment of around 520 using figures in the round were fortunately used as infill for new buildings after the Persian sack in 480 BCE, and recovered from the 1880s on in fresh unweathered condition. Other significant remains of architectural sculpture come from Paestum in Italy, Corfu, Delphi and the Temple of Aphaea in Aegina (much now in Munich).[44] Most Greek sculpture originally included at least some colour; the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek Museum in Copenhagen, Denmark, has done extensive research and recreation of the original colours.[45][46]

Cycladic statue 2700–2300 BCE. Head from the figure of a woman, H. 27 centimetres (11 in)

Cycladic statue 2700–2300 BCE. Head from the figure of a woman, H. 27 centimetres (11 in) Cycladic Female Figurine, c. 2500–2400 BCE, 41.5 cm (16.3 in) high

Cycladic Female Figurine, c. 2500–2400 BCE, 41.5 cm (16.3 in) high- Mycenae, 1600−1500 BCE. Silver rhyton with gold horns and rosette on the forehead

_MET_DT263.jpg) Lifesize New York Kouros, c. 590–580 BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lifesize New York Kouros, c. 590–580 BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Late Archaic warrior from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaea, c. 500

Late Archaic warrior from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaea, c. 500 The Amathus sarcophagus, from Amathus, Cyprus, 2nd quarter of the 5th century BCE Archaic period, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Amathus sarcophagus, from Amathus, Cyprus, 2nd quarter of the 5th century BCE Archaic period, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Classical

There are fewer original remains from the first phase of the Classical period, often called the Severe style; free-standing statues were now mostly made in bronze, which always had value as scrap. The Severe style lasted from around 500 in reliefs, and soon after 480 in statues, to about 450. The relatively rigid poses of figures relaxed, and asymmetrical turning positions and oblique views became common, and deliberately sought. This was combined with a better understanding of anatomy and the harmonious structure of sculpted figures, and the pursuit of naturalistic representation as an aim, which had not been present before. Excavations at the Temple of Zeus, Olympia since 1829 have revealed the largest group of remains, from about 460, of which many are in the Louvre.[47]

The "High Classical" period lasted only a few decades from about 450 to 400, but has had a momentous influence on art, and retains a special prestige, despite a very restricted number of original survivals. The best known works are the Parthenon Marbles, traditionally (since Plutarch) executed by a team led by the most famous ancient Greek sculptor Phidias, active from about 465–425, who was in his own day more famous for his colossal chryselephantine Statue of Zeus at Olympia (c. 432), one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, his Athena Parthenos (438), the cult image of the Parthenon, and Athena Promachos, a colossal bronze figure that stood next to the Parthenon; all of these are lost but are known from many representations. He is also credited as the creator of some life-size bronze statues known only from later copies whose identification is controversial, including the Ludovisi Hermes.[48]

The High Classical style continued to develop realism and sophistication in the human figure, and improved the depiction of drapery (clothes), using it to add to the impact of active poses. Facial expressions were usually very restrained, even in combat scenes. The composition of groups of figures in reliefs and on pediments combined complexity and harmony in a way that had a permanent influence on Western art. Relief could be very high indeed, as in the Parthenon illustration below, where most of the leg of the warrior is completely detached from the background, as were the missing parts; relief this high made sculptures more subject to damage.[49] The Late Classical style developed the free-standing female nude statue, supposedly an innovation of Praxiteles, and developed increasingly complex and subtle poses that were interesting when viewed from a number of angles, as well as more expressive faces; both trends were to be taken much further in the Hellenistic period.[50]

Hellenistic

The Hellenistic period is conventionally dated from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, and ending either with the final conquest of the Greek heartlands by Rome in 146 BCE or with the final defeat of the last remaining successor-state to Alexander's empire after the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, which also marks the end of Republican Rome.[51] It is thus much longer than the previous periods, and includes at least two major phases: a "Pergamene" style of experimentation, exuberance and some sentimentality and vulgarity, and in the 2nd century BCE a classicising return to a more austere simplicity and elegance; beyond such generalizations dating is typically very uncertain, especially when only later copies are known, as is usually the case. The initial Pergamene style was not especially associated with Pergamon, from which it takes its name, but the very wealthy kings of that state were among the first to collect and also copy Classical sculpture, and also commissioned much new work, including the famous Pergamon Altar whose sculpture is now mostly in Berlin and which exemplifies the new style, as do the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (another of the Seven Wonders), the famous Laocoön and his Sons in the Vatican Museums, a late example, and the bronze original of The Dying Gaul (illustrated at top), which we know was part of a group actually commissioned for Pergamon in about 228 BCE, from which the Ludovisi Gaul was also a copy. The group called the Farnese Bull, possibly a 2nd-century marble original, is still larger and more complex,[52]

Hellenistic sculpture greatly expanded the range of subjects represented, partly as a result of greater general prosperity, and the emergence of a very wealthy class who had large houses decorated with sculpture, although we know that some examples of subjects that seem best suited to the home, such as children with animals, were in fact placed in temples or other public places. For a much more popular home decoration market there were Tanagra figurines, and those from other centres where small pottery figures were produced on an industrial scale, some religious but others showing animals and elegantly dressed ladies. Sculptors became more technically skilled in representing facial expressions conveying a wide variety of emotions and the portraiture of individuals, as well representing different ages and races. The reliefs from the Mausoleum are rather atypical in that respect; most work was free-standing, and group compositions with several figures to be seen in the round, like the Laocoon and the Pergamon group celebrating victory over the Gauls became popular, having been rare before. The Barberini Faun, showing a satyr sprawled asleep, presumably after drink, is an example of the moral relaxation of the period, and the readiness to create large and expensive sculptures of subjects that fall short of the heroic.[53]

After the conquests of Alexander Hellenistic culture was dominant in the courts of most of the Near East, and some of Central Asia, and increasingly being adopted by European elites, especially in Italy, where Greek colonies initially controlled most of the South. Hellenistic art, and artists, spread very widely, and was especially influential in the expanding Roman Republic and when it encountered Buddhism in the easternmost extensions of the Hellenistic area. The massive so-called Alexander Sarcophagus found in Sidon in modern Lebanon, was probably made there at the start of the period by expatriate Greek artists for a Hellenized Persian governor.[54] The wealth of the period led to a greatly increased production of luxury forms of small sculpture, including engraved gems and cameos, jewellery, and gold and silverware.

The Riace Bronzes, very rare bronze figures recovered from the sea, c. 460–430

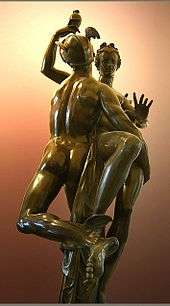

The Riace Bronzes, very rare bronze figures recovered from the sea, c. 460–430 Hermes and the Infant Dionysos, possibly an original by Praxiteles, 4th century

Hermes and the Infant Dionysos, possibly an original by Praxiteles, 4th century- Two elegant ladies, pottery figurines, 350–300

Bronze Statuette of a Horse, late 2nd – 1st century BCE Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bronze Statuette of a Horse, late 2nd – 1st century BCE Metropolitan Museum of Art The Winged Victory of Samothrace, c. 190 BCE, Louvre

The Winged Victory of Samothrace, c. 190 BCE, Louvre

Laocoön and his Sons, Greek, (Late Hellenistic), perhaps a copy, between 200 BCE and 20 CE, white marble, Vatican Museum

Laocoön and his Sons, Greek, (Late Hellenistic), perhaps a copy, between 200 BCE and 20 CE, white marble, Vatican Museum- Leochares, Apollo Belvedere, c. 130–140 CE. Roman copy after a Greek bronze original of 330–320 BCE. Vatican Museums

Europe after the Greeks

Roman sculpture

Early Roman art was influenced by the art of Greece and that of the neighbouring Etruscans, themselves greatly influenced by their Greek trading partners. An Etruscan speciality was near life size tomb effigies in terracotta, usually lying on top of a sarcophagus lid propped up on one elbow in the pose of a diner in that period. As the expanding Roman Republic began to conquer Greek territory, at first in Southern Italy and then the entire Hellenistic world except for the Parthian far east, official and patrician sculpture became largely an extension of the Hellenistic style, from which specifically Roman elements are hard to disentangle, especially as so much Greek sculpture survives only in copies of the Roman period.[55] By the 2nd century BCE, "most of the sculptors working at Rome" were Greek,[56] often enslaved in conquests such as that of Corinth (146 BCE), and sculptors continued to be mostly Greeks, often slaves, whose names are very rarely recorded. Vast numbers of Greek statues were imported to Rome, whether as booty or the result of extortion or commerce, and temples were often decorated with re-used Greek works.[57]

A native Italian style can be seen in the tomb monuments, which very often featured portrait busts, of prosperous middle-class Romans, and portraiture is arguably the main strength of Roman sculpture. There are no survivals from the tradition of masks of ancestors that were worn in processions at the funerals of the great families and otherwise displayed in the home, but many of the busts that survive must represent ancestral figures, perhaps from the large family tombs like the Tomb of the Scipios or the later mausolea outside the city. The famous bronze head supposedly of Lucius Junius Brutus is very variously dated, but taken as a very rare survival of Italic style under the Republic, in the preferred medium of bronze.[58] Similarly stern and forceful heads are seen on coins of the Late Republic, and in the Imperial period coins as well as busts sent around the Empire to be placed in the basilicas of provincial cities were the main visual form of imperial propaganda; even Londinium had a near-colossal statue of Nero, though far smaller than the 30-metre-high Colossus of Nero in Rome, now lost.[59]

The Romans did not generally attempt to compete with free-standing Greek works of heroic exploits from history or mythology, but from early on produced historical works in relief, culminating in the great Roman triumphal columns with continuous narrative reliefs winding around them, of which those commemorating Trajan (CE 113) and Marcus Aurelius (by 193) survive in Rome, where the Ara Pacis ("Altar of Peace", 13 BCE) represents the official Greco-Roman style at its most classical and refined. Among other major examples are the earlier re-used reliefs on the Arch of Constantine and the base of the Column of Antoninus Pius (161),[60] Campana reliefs were cheaper pottery versions of marble reliefs and the taste for relief was from the imperial period expanded to the sarcophagus. All forms of luxury small sculpture continued to be patronized, and quality could be extremely high, as in the silver Warren Cup, glass Lycurgus Cup, and large cameos like the Gemma Augustea, Gonzaga Cameo and the "Great Cameo of France".[61] For a much wider section of the population, moulded relief decoration of pottery vessels and small figurines were produced in great quantity and often considerable quality.[62]

After moving through a late 2nd-century "baroque" phase,[63] in the 3rd century, Roman art largely abandoned, or simply became unable to produce, sculpture in the classical tradition, a change whose causes remain much discussed. Even the most important imperial monuments now showed stumpy, large-eyed figures in a harsh frontal style, in simple compositions emphasizing power at the expense of grace. The contrast is famously illustrated in the Arch of Constantine of 315 in Rome, which combines sections in the new style with roundels in the earlier full Greco-Roman style taken from elsewhere, and the Four Tetrarchs (c. 305) from the new capital of Constantinople, now in Venice. Ernst Kitzinger found in both monuments the same "stubby proportions, angular movements, an ordering of parts through symmetry and repetition and a rendering of features and drapery folds through incisions rather than modelling... The hallmark of the style wherever it appears consists of an emphatic hardness, heaviness and angularity—in short, an almost complete rejection of the classical tradition".[64]

This revolution in style shortly preceded the period in which Christianity was adopted by the Roman state and the great majority of the people, leading to the end of large religious sculpture, with large statues now only used for emperors. However, rich Christians continued to commission reliefs for sarcophagi, as in the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, and very small sculpture, especially in ivory, was continued by Christians, building on the style of the consular diptych.[65]

- Etruscan sarcophagus, 3rd century BCE

The "Capitoline Brutus", dated to the 3rd or 1st century BCE

The "Capitoline Brutus", dated to the 3rd or 1st century BCE

- Tomb relief of the Decii, 98–117 CE

Bust of Emperor Claudius, c. 50 CE, (reworked from a bust of emperor Caligula), It was found in the so-called Otricoli basilica in Lanuvium, Italy, Vatican Museums

Bust of Emperor Claudius, c. 50 CE, (reworked from a bust of emperor Caligula), It was found in the so-called Otricoli basilica in Lanuvium, Italy, Vatican Museums

The Four Tetrarchs, c. 305, showing the new anti-classical style, in porphyry, now San Marco, Venice

The Four Tetrarchs, c. 305, showing the new anti-classical style, in porphyry, now San Marco, Venice The cameo gem known as the "Great Cameo of France", c. 23 CE, with an allegory of Augustus and his family

The cameo gem known as the "Great Cameo of France", c. 23 CE, with an allegory of Augustus and his family

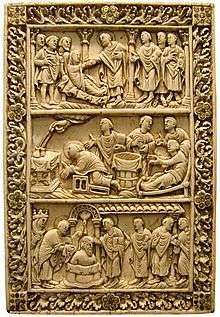

Early Medieval and Byzantine

The Early Christians were opposed to monumental religious sculpture, though continuing Roman traditions in portrait busts and sarcophagus reliefs, as well as smaller objects such as the consular diptych. Such objects, often in valuable materials, were also the main sculptural traditions (as far as is known) of the barbaric civilizations of the Migration period, as seen in the objects found in the 6th-century burial treasure at Sutton Hoo, and the jewellery of Scythian art and the hybrid Christian and animal style productions of Insular art. Following the continuing Byzantine tradition, Carolingian art revived ivory carving, often in panels for the treasure bindings of grand illuminated manuscripts, as well as crozier heads and other small fittings.

Byzantine art, though producing superb ivory reliefs and architectural decorative carving, never returned to monumental sculpture, or even much small sculpture in the round.[66] However, in the West during the Carolingian and Ottonian periods there was the beginnings of a production of monumental statues, in courts and major churches. This gradually spread; by the late 10th and 11th century there are records of several apparently life-size sculptures in Anglo-Saxon churches, probably of precious metal around a wooden frame, like the Golden Madonna of Essen. No Anglo-Saxon example has survived,[67] and survivals of large non-architectural sculpture from before 1,000 are exceptionally rare. Much the finest is the Gero Cross, of 965–970, which is a crucifix, which was evidently the commonest type of sculpture; Charlemagne had set one up in the Palatine Chapel in Aachen around 800. These continued to grow in popularity, especially in Germany and Italy. The rune stones of the Nordic world, the Pictish stones of Scotland and possibly the high cross reliefs of Christian Great Britain, were northern sculptural traditions that bridged the period of Christianization.

Archangel Ivory, 525–550, Constantinople

Archangel Ivory, 525–550, Constantinople Late Carolingian ivory panel, probably meant for a book-cover

Late Carolingian ivory panel, probably meant for a book-cover

Romanesque

From about 1000 there was a general rebirth of artistic production in all Europe, led by general economic growth in production and commerce, and the new style of Romanesque art was the first medieval style to be used in the whole of Western Europe. The new cathedrals and pilgrim's churches were increasingly decorated with architectural stone reliefs, and new focuses for sculpture developed, such as the tympanum over church doors in the 12th century, and the inhabited capital with figures and often narrative scenes. Outstanding abbey churches with sculpture include in France Vézelay and Moissac and in Spain Silos.[68]

Romanesque art was characterised by a very vigorous style in both sculpture and painting. The capitals of columns were never more exciting than in this period, when they were often carved with complete scenes with several figures.[69] The large wooden crucifix was a German innovation right at the start of the period, as were free-standing statues of the enthroned Madonna, but the high relief was above all the sculptural mode of the period. Compositions usually had little depth, and needed to be flexible to squeeze themselves into the shapes of capitals, and church typanums; the tension between a tightly enclosing frame, from which the composition sometimes escapes, is a recurrent theme in Romanesque art. Figures still often varied in size in relation to their importance portraiture hardly existed.

Objects in precious materials such as ivory and metal had a very high status in the period, much more so than monumental sculpture — we know the names of more makers of these than painters, illuminators or architect-masons. Metalwork, including decoration in enamel, became very sophisticated, and many spectacular shrines made to hold relics have survived, of which the best known is the Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne Cathedral by Nicholas of Verdun. The bronze Gloucester candlestick and the brass font of 1108–17 now in Liège are superb examples, very different in style, of metal casting, the former highly intricate and energetic, drawing on manuscript painting, while the font shows the Mosan style at its most classical and majestic. The bronze doors, a triumphal column and other fittings at Hildesheim Cathedral, the Gniezno Doors, and the doors of the Basilica di San Zeno in Verona are other substantial survivals. The aquamanile, a container for water to wash with, appears to have been introduced to Europe in the 11th century, and often took fantastic zoomorphic forms; surviving examples are mostly in brass. Many wax impressions from impressive seals survive on charters and documents, although Romanesque coins are generally not of great aesthetic interest.[70]

The Cloisters Cross is an unusually large ivory crucifix, with complex carving including many figures of prophets and others, which has been attributed to one of the relatively few artists whose name is known, Master Hugo, who also illuminated manuscripts. Like many pieces it was originally partly coloured. The Lewis chessmen are well-preserved examples of small ivories, of which many pieces or fragments remain from croziers, plaques, pectoral crosses and similar objects.

The tympanum of Vézelay Abbey, Burgundy, France, 1130s

The tympanum of Vézelay Abbey, Burgundy, France, 1130s.jpg) Facade, Cathedral of Ourense 1160, Spain

Facade, Cathedral of Ourense 1160, Spain Pórtico da Gloria, Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain, c. 12th–13th centuries

Pórtico da Gloria, Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain, c. 12th–13th centuries

Gothic

The Gothic period is essentially defined by Gothic architecture, and does not entirely fit with the development of style in sculpture in either its start or finish. The facades of large churches, especially around doors, continued to have large typanums, but also rows of sculpted figures spreading around them. The statues on the Western (Royal) Portal at Chartres Cathedral (c. 1145) show an elegant but exaggerated columnar elongation, but those on the south transept portal, from 1215 to 1220, show a more naturalistic style and increasing detachment from the wall behind, and some awareness of the classical tradition. These trends were continued in the west portal at Reims Cathedral of a few years later, where the figures are almost in the round, as became usual as Gothic spread across Europe.[71]

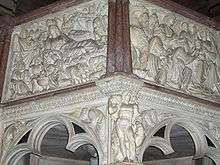

In Italy Nicola Pisano (1258–1278) and his son Giovanni developed a style that is often called Proto-Renaissance, with unmistakable influence from Roman sarcophagi and sophisticated and crowded compositions, including a sympathetic handling of nudity, in relief panels on their pulpit of Siena Cathedral (1265–68), the Fontana Maggiore in Perugia, and Giovanni's pulpit in Pistoia of 1301.[72] Another revival of classical style is seen in the International Gothic work of Claus Sluter and his followers in Burgundy and Flanders around 1400.[73] Late Gothic sculpture continued in the North, with a fashion for very large wooden sculpted altarpieces with increasingly virtuoso carving and large numbers agitated expressive figures; most surviving examples are in Germany, after much iconoclasm elsewhere. Tilman Riemenschneider, Veit Stoss and others continued the style well into the 16th century, gradually absorbing Italian Renaissance influences.[74]

Life-size tomb effigies in stone or alabaster became popular for the wealthy, and grand multi-level tombs evolved, with the Scaliger Tombs of Verona so large they had to be moved outside the church. By the 15th century there was an industry exporting Nottingham alabaster altar reliefs in groups of panels over much of Europe for economical parishes who could not afford stone retables.[75] Small carvings, for a mainly lay and often female market, became a considerable industry in Paris and some other centres. Types of ivories included small devotional polyptychs, single figures, especially of the Virgin, mirror-cases, combs, and elaborate caskets with scenes from Romances, used as engagement presents.[76] The very wealthy collected extravagantly elaborate jewelled and enamelled metalwork, both secular and religious, like the Duc de Berry's Holy Thorn Reliquary, until they ran short of money, when they were melted down again for cash.[77]

West portal of Chartres Cathedral (c. 1145)

West portal of Chartres Cathedral (c. 1145)- South portal of Chartres Cathedral (c. 1215–1220)

West portal at Reims Cathedral, Annunciation group

West portal at Reims Cathedral, Annunciation group

- The Bamberg Horseman 1237, near life-size stone equestrian statue, the first of this kind since antiquity.

Lid of the Walters Casket, with the Siege of the Castle of Love at left, and jousting. Paris, 1330–1350

Lid of the Walters Casket, with the Siege of the Castle of Love at left, and jousting. Paris, 1330–1350 Siege of the Castle of Love on a mirror-case in the Louvre, 1350–1370; the ladies are losing.

Siege of the Castle of Love on a mirror-case in the Louvre, 1350–1370; the ladies are losing. Central German Pietà, 1330–1340

Central German Pietà, 1330–1340 Claus Sluter, David and a prophet from the Well of Moses

Claus Sluter, David and a prophet from the Well of Moses Base of the Holy Thorn Reliquary, a Resurrection of the Dead in gold, enamel and gems

Base of the Holy Thorn Reliquary, a Resurrection of the Dead in gold, enamel and gems Section of a panelled altarpiece with Resurrection of Christ, English, 1450–1490, Nottingham alabaster with remains of colour

Section of a panelled altarpiece with Resurrection of Christ, English, 1450–1490, Nottingham alabaster with remains of colour- Detail of the Last Supper from Tilman Riemenschneider's Altar of the Holy Blood, 1501–1505, Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Bavaria

Renaissance

Renaissance sculpture proper is often taken to begin with the famous competition for the doors of the Florence Baptistry in 1403, from which the trial models submitted by the winner, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Filippo Brunelleschi survive. Ghiberti's doors are still in place, but were undoubtedly eclipsed by his second pair for the other entrance, the so-called Gates of Paradise, which took him from 1425 to 1452, and are dazzlingly confident classicizing compositions with varied depths of relief allowing extensive backgrounds.[78] The intervening years had seen Ghiberti's early assistant Donatello develop with seminal statues including his Davids in marble (1408–09) and bronze (1440s), and his Equestrian statue of Gattamelata, as well as reliefs.[79] A leading figure in the later period was Andrea del Verrocchio, best known for his equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni in Venice;[80] his pupil Leonardo da Vinci designed an equine sculpture in 1482 The Horse for Milan-but only succeeded in making a 24-foot (7.3 m) clay model which was destroyed by French archers in 1499, and his other ambitious sculptural plans were never completed.[81]

The period was marked by a great increase in patronage of sculpture by the state for public art and by the wealthy for their homes; especially in Italy, public sculpture remains a crucial element in the appearance of historic city centres. Church sculpture mostly moved inside just as outside public monuments became common. Portrait sculpture, usually in busts, became popular in Italy around 1450, with the Neapolitan Francesco Laurana specializing in young women in meditative poses, while Antonio Rossellino and others more often depicted knobbly-faced men of affairs, but also young children.[82] The portrait medal invented by Pisanello also often depicted women; relief plaquettes were another new small form of sculpture in cast metal.

Michelangelo was an active sculptor from about 1500 to 1520, and his great masterpieces including his David, Pietà, Moses, and pieces for the Tomb of Pope Julius II and Medici Chapel could not be ignored by subsequent sculptors. His iconic David (1504) has a contrapposto pose, borrowed from classical sculpture. It differs from previous representations of the subject in that David is depicted before his battle with Goliath and not after the giant's defeat. Instead of being shown victorious, as Donatello and Verocchio had done, David looks tense and battle ready.[83]

Lorenzo Ghiberti, panel of the Sacrifice of Isaac from the Florence Baptistry doors; oblique view here

Lorenzo Ghiberti, panel of the Sacrifice of Isaac from the Florence Baptistry doors; oblique view here Luca della Robbia, detail of Cantoria, c. 1438, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence

Luca della Robbia, detail of Cantoria, c. 1438, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence

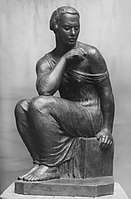

Francesco Laurana, female bust (cast)

Francesco Laurana, female bust (cast)

Michelangelo, Dying Slave, c. 1513–1516

Michelangelo, Dying Slave, c. 1513–1516

Mannerist

As in painting, early Italian Mannerist sculpture was very largely an attempt to find an original style that would top the achievement of the High Renaissance, which in sculpture essentially meant Michelangelo, and much of the struggle to achieve this was played out in commissions to fill other places in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, next to Michelangelo's David. Baccio Bandinelli took over the project of Hercules and Cacus from the master himself, but it was little more popular than it is now, and maliciously compared by Benvenuto Cellini to "a sack of melons", though it had a long-lasting effect in apparently introducing relief panels on the pedestal of statues. Like other works of his and other Mannerists it removes far more of the original block than Michelangelo would have done.[84] Cellini's bronze Perseus with the head of Medusa is certainly a masterpiece, designed with eight angles of view, another Mannerist characteristic, but is indeed mannered compared to the Davids of Michelangelo and Donatello.[85] Originally a goldsmith, his famous gold and enamel Salt Cellar (1543) was his first sculpture, and shows his talent at its best.[86] As these examples show, the period extended the range of secular subjects for large works beyond portraits, with mythological figures especially favoured; previously these had mostly been found in small works.

Small bronze figures for collector's cabinets, often mythological subjects with nudes, were a popular Renaissance form at which Giambologna, originally Flemish but based in Florence, excelled in the later part of the century, also creating life-size sculptures, of which two joined the collection in the Piazza della Signoria. He and his followers devised elegant elongated examples of the figura serpentinata, often of two intertwined figures, that were interesting from all angles.[87]

Stucco overdoor at Fontainebleau, probably designed by Primaticcio, who painted the oval inset, 1530s or 1540s

Stucco overdoor at Fontainebleau, probably designed by Primaticcio, who painted the oval inset, 1530s or 1540s Benvenuto Cellini, Perseus with the head of Medusa, 1545–1554

Benvenuto Cellini, Perseus with the head of Medusa, 1545–1554 Giambologna, Samson Slaying a Philistine, about 1562

Giambologna, Samson Slaying a Philistine, about 1562

Baroque and Rococo

.jpg)

In Baroque sculpture, groups of figures assumed new importance, and there was a dynamic movement and energy of human forms— they spiralled around an empty central vortex, or reached outwards into the surrounding space. Baroque sculpture often had multiple ideal viewing angles, and reflected a general continuation of the Renaissance move away from the relief to sculpture created in the round, and designed to be placed in the middle of a large space—elaborate fountains such as Bernini's Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi (Rome, 1651), or those in the Gardens of Versailles were a Baroque speciality. The Baroque style was perfectly suited to sculpture, with Gian Lorenzo Bernini the dominating figure of the age in works such as The Ecstasy of St Theresa (1647–1652).[88] Much Baroque sculpture added extra-sculptural elements, for example, concealed lighting, or water fountains, or fused sculpture and architecture to create a transformative experience for the viewer. Artists saw themselves as in the classical tradition, but admired Hellenistic and later Roman sculpture, rather than that of the more "Classical" periods as they are seen today.[89]

The Protestant Reformation brought an almost total stop to religious sculpture in much of Northern Europe, and though secular sculpture, especially for portrait busts and tomb monuments, continued, the Dutch Golden Age has no significant sculptural component outside goldsmithing.[90] Partly in direct reaction, sculpture was as prominent in Roman Catholicism as in the late Middle Ages. Statues of rulers and the nobility became increasingly popular. In the 18th century much sculpture continued on Baroque lines—the Trevi Fountain was only completed in 1762. Rococo style was better suited to smaller works, and arguably found its ideal sculptural form in early European porcelain, and interior decorative schemes in wood or plaster such as those in French domestic interiors and Austrian and Bavarian pilgrimage churches.[91]

Bust of Louis XIV, 1686, by Antoine Coysevox

Bust of Louis XIV, 1686, by Antoine Coysevox Saint Veronica by Francesco Mochi (1640), Saint Peter's Basilica

Saint Veronica by Francesco Mochi (1640), Saint Peter's Basilica Pierre Paul Puget, Perseus and Andromeda, 1715, Musée du Louvre

Pierre Paul Puget, Perseus and Andromeda, 1715, Musée du Louvre Franz Anton Bustelli, Rococo Nymphenburg Porcelain group

Franz Anton Bustelli, Rococo Nymphenburg Porcelain group

Neo-Classical

The Neoclassical style that arrived in the late 18th century gave great emphasis to sculpture. Jean-Antoine Houdon exemplifies the penetrating portrait sculpture the style could produce, and Antonio Canova's nudes the idealist aspect of the movement. The Neoclassical period was one of the great ages of public sculpture, though its "classical" prototypes were more likely to be Roman copies of Hellenistic sculptures. In sculpture, the most familiar representatives are the Italian Antonio Canova, the Englishman John Flaxman and the Dane Bertel Thorvaldsen. The European neoclassical manner also took hold in the United States, where its pinnacle occurred somewhat later and is exemplified in the sculptures of Hiram Powers.

_MET_DT2883.jpg)

John Flaxman, Memorial in the church at Badger, Shropshire, c. 1780s

John Flaxman, Memorial in the church at Badger, Shropshire, c. 1780s

Asia

Greco-Buddhist sculpture and Asia

Greco-Buddhist art is the artistic manifestation of Greco-Buddhism, a cultural syncretism between the Classical Greek culture and Buddhism, which developed over a period of close to 1000 years in Central Asia, between the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE, and the Islamic conquests of the 7th century CE. Greco-Buddhist art is characterized by the strong idealistic realism of Hellenistic art and the first representations of the Buddha in human form, which have helped define the artistic (and particularly, sculptural) canon for Buddhist art throughout the Asian continent up to the present. Though dating is uncertain, it appears that strongly Hellenistic styles lingered in the East for several centuries after they had declined around the Mediterranean, as late as the 5th century CE. Some aspects of Greek art were adopted while others did not spread beyond the Greco-Buddhist area; in particular the standing figure, often with a relaxed pose and one leg flexed, and the flying cupids or victories, who became popular across Asia as apsaras. Greek foliage decoration was also influential, with Indian versions of the Corinthian capital appearing.[92]

The origins of Greco-Buddhist art are to be found in the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian kingdom (250–130 BCE), located in today's Afghanistan, from which Hellenistic culture radiated into the Indian subcontinent with the establishment of the small Indo-Greek kingdom (180–10 BCE). Under the Indo-Greeks and then the Kushans, the interaction of Greek and Buddhist culture flourished in the area of Gandhara, in today's northern Pakistan, before spreading further into India, influencing the art of Mathura, and then the Hindu art of the Gupta empire, which was to extend to the rest of South-East Asia. The influence of Greco-Buddhist art also spread northward towards Central Asia, strongly affecting the art of the Tarim Basin and the Dunhuang Caves, and ultimately the sculpted figure in China, Korea, and Japan.[93]

- Gandhara frieze with devotees, holding plantain leaves, in purely Hellenistic style, inside Corinthian columns, 1st–2nd century CE. Buner, Swat, Pakistan. Victoria and Albert Museum

Coin of Demetrius I of Bactria, who reigned circa 200–180 BCE and invaded Northern India

Coin of Demetrius I of Bactria, who reigned circa 200–180 BCE and invaded Northern India Stucco Buddha head, once painted, from Hadda, Afghanistan, 3rd–4th centuries

Stucco Buddha head, once painted, from Hadda, Afghanistan, 3rd–4th centuries- Gandhara Poseidon (Ancient Orient Museum)

Taller Buddha of Bamiyan, c. 547 CE, in 1963 and in 2008 after they were dynamited and destroyed in March 2001 by the Taliban

Taller Buddha of Bamiyan, c. 547 CE, in 1963 and in 2008 after they were dynamited and destroyed in March 2001 by the Taliban

China

Chinese ritual bronzes from the Shang and Western Zhou Dynasties come from a period of over a thousand years from c. 1500 BCE, and have exerted a continuing influence over Chinese art. They are cast with complex patterned and zoomorphic decoration, but avoid the human figure, unlike the huge figures only recently discovered at Sanxingdui.[94] The spectacular Terracotta Army was assembled for the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China from 221–210 BCE, as a grand imperial version of the figures long placed in tombs to enable the deceased to enjoy the same lifestyle in the afterlife as when alive, replacing actual sacrifices of very early periods. Smaller figures in pottery or wood were placed in tombs for many centuries afterwards, reaching a peak of quality in Tang dynasty tomb figures.[95] The tradition of unusually large pottery figures persisted in China, through Tang sancai tomb figures to later Buddhist statues such as the near life-size set of Yixian glazed pottery luohans and later figures for temples and tombs. These came to replace earlier equivalents in wood.

Native Chinese religions do not usually use cult images of deities, or even represent them, and large religious sculpture is nearly all Buddhist, dating mostly from the 4th to the 14th century, and initially using Greco-Buddhist models arriving via the Silk Road. Buddhism is also the context of all large portrait sculpture; in total contrast to some other areas, in medieval China even painted images of the emperor were regarded as private. Imperial tombs have spectacular avenues of approach lined with real and mythological animals on a scale matching Egypt, and smaller versions decorate temples and palaces.[96]

Small Buddhist figures and groups were produced to a very high quality in a range of media,[97] as was relief decoration of all sorts of objects, especially in metalwork and jade.[98] In the earlier periods, large quantities of sculpture were cut from the living rock in pilgrimage cave-complexes, and as outside rock reliefs. These were mostly originally painted. In notable contrast to literati painters, sculptors of all sorts were regarded as artisans and very few names are recorded.[99] From the Ming dynasty onwards, statuettes of religious and secular figures were produced in Chinese porcelain and other media, which became an important export.

A bronze ding from late Shang dynasty (13th century–10th century BCE)

A bronze ding from late Shang dynasty (13th century–10th century BCE) A tomb guardian usually placed inside the doors of the tomb to protect or guide the soul, Warring States period, c. 3rd century BCE

A tomb guardian usually placed inside the doors of the tomb to protect or guide the soul, Warring States period, c. 3rd century BCE- Lifesize calvalryman from the Terracotta Army, Qin dynasty, c. 3rd century BCE

Tomb figure of dancing girl, Han Dynasty (202 BCE—220 CE)

Tomb figure of dancing girl, Han Dynasty (202 BCE—220 CE) Bronze cowrie container with yaks, from the Dian Kingdom (4th century BCE – 109 BCE) tradition of the Western Han

Bronze cowrie container with yaks, from the Dian Kingdom (4th century BCE – 109 BCE) tradition of the Western Han Northern Wei dynasty Maitreya (386–534)

Northern Wei dynasty Maitreya (386–534) Tang dynasty tomb figure in sancai glaze pottery, horse and groom (618–907)

Tang dynasty tomb figure in sancai glaze pottery, horse and groom (618–907) Seated Buddha, Tang dynasty c. 650.

Seated Buddha, Tang dynasty c. 650. The Leshan Giant Buddha, Tang dynasty, completed in 803.

The Leshan Giant Buddha, Tang dynasty, completed in 803. A wooden Bodhisattva from the Song dynasty (960–1279)

A wooden Bodhisattva from the Song dynasty (960–1279) Chinese jade Cup with Dragon Handles, Song dynasty, 12th century

Chinese jade Cup with Dragon Handles, Song dynasty, 12th century Guanyin Bodhisattva in Blanc de Chine (Dehua porcelain), by He Chaozong, Ming dynasty, early 17th century

Guanyin Bodhisattva in Blanc de Chine (Dehua porcelain), by He Chaozong, Ming dynasty, early 17th century- Blue underglaze statue of a man with his pipe, Jingdezhen porcelain, Ming Wanli period (1573–1620)

.jpg) A Chinese guardian lion outside Yonghe Temple, Beijing, Qing dynasty, c. 1694

A Chinese guardian lion outside Yonghe Temple, Beijing, Qing dynasty, c. 1694

Japan

Towards the end of the long Neolithic Jōmon period, some pottery vessels were "flame-rimmed" with extravagant extensions to the rim that can only be called sculptural,[100] and very stylized pottery dogū figures were produced, many with the characteristic "snow-goggle" eyes. During the Kofun period of the 3rd to 6th century CE, haniwa terracotta figures of humans and animals in a simplistic style were erected outside important tombs. The arrival of Buddhism in the 6th century brought with it sophisticated traditions in sculpture, Chinese styles mediated via Korea. The 7th-century Hōryū-ji and its contents have survived more intact than any East Asian Buddhist temple of its date, with works including a Shaka Trinity of 623 in bronze, showing the historical Buddha flanked by two bodhisattvas and also the Guardian Kings of the Four Directions.[101]

The wooden image (9th century) of Shakyamuni, the "historic" Buddha, enshrined in a secondary building at the Murō-ji, is typical of the early Heian sculpture, with its ponderous body, covered by thick drapery folds carved in the hompa-shiki (rolling-wave) style, and its austere, withdrawn facial expression. The Kei school of sculptors, particularly Unkei, created a new, more realistic style of sculpture.

Almost all subsequent significant large sculpture in Japan was Buddhist, with some Shinto equivalents, and after Buddhism declined in Japan in the 15th century, monumental sculpture became largely architectural decoration and less significant.[102] However sculptural work in the decorative arts was developed to a remarkable level of technical achievement and refinement in small objects such as inro and netsuke in many materials, and metal tosogu or Japanese sword mountings. In the 19th century there were export industries of small bronze sculptures of extreme virtuosity, ivory and porcelain figurines, and other types of small sculpture, increasingly emphasizing technical accomplishment.

Dogū with "snow-goggle" eyes, 1000–400 BCE

Dogū with "snow-goggle" eyes, 1000–400 BCE- 6th-century haniwa figure

Kongo Rishiki (Guardian Deity) at the Central Gate of Hōryū-ji

Kongo Rishiki (Guardian Deity) at the Central Gate of Hōryū-ji.jpg) Priest Ganjin (Jianzhen), Nara period, 8th century

Priest Ganjin (Jianzhen), Nara period, 8th century

Tsuba sword fitting with a "Rabbit Viewing the Autumn Moon", bronze, gold and silver, between 1670 and 1744

Tsuba sword fitting with a "Rabbit Viewing the Autumn Moon", bronze, gold and silver, between 1670 and 1744 Izumiya Tomotada, netsuke in the form of a dog, late 18th century

Izumiya Tomotada, netsuke in the form of a dog, late 18th century Eagle by Suzuki Chokichi, 1892, Tokyo National Museum

Eagle by Suzuki Chokichi, 1892, Tokyo National Museum Yamada Chōzaburō, Wind God in repoussé iron, c. 1915

Yamada Chōzaburō, Wind God in repoussé iron, c. 1915

India

The first known sculpture in the Indian subcontinent is from the Indus Valley civilization (3300–1700 BCE), found in sites at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa in modern-day Pakistan. These include the famous small bronze female dancer. However, such figures in bronze and stone are rare and greatly outnumbered by pottery figurines and stone seals, often of animals or deities very finely depicted. After the collapse of the Indus Valley civilization there is little record of sculpture until the Buddhist era, apart from a hoard of copper figures of (somewhat controversially) c. 1500 BCE from Daimabad.[103] Thus the great tradition of Indian monumental sculpture in stone appears to begin, relative to other cultures, and the development of Indian civilization, relatively late, with the reign of Asoka from 270 to 232 BCE, and the Pillars of Ashoka he erected around India, carrying his edicts and topped by famous sculptures of animals, mostly lions, of which six survive.[104] Large amounts of figurative sculpture, mostly in relief, survive from Early Buddhist pilgrimage stupas, above all Sanchi; these probably developed out of a tradition using wood that also embraced Hinduism.[105]