Indian Ocean trade

Indian Ocean Trade (whose trade routes are sometimes collectively called the Monsoon Marketplace)[1][2][3] has been a key factor in East–West exchanges throughout history. Long distance trade in dhows and proas made it a dynamic zone of interaction between peoples, cultures, and civilizations stretching from Java in the East to Zanzibar and Mombasa in the West. Cities and states on the Indian Ocean rim focused on both the sea and the land.

Early period

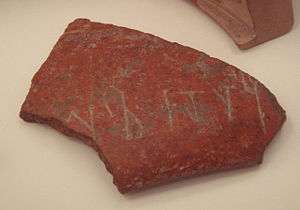

There was an extensive maritime trade network operating between the Harappan and Mesopotamian civilizations as early as the middle Harappan Phase (2600-1900 BCE), with much commerce being handled by "middlemen merchants from Dilmun" (modern Bahrain and Failaka located in the Persian Gulf).[4] Such long-distance sea trade became feasible with the development of plank-built watercraft, equipped with a single central mast supporting a sail of woven rushes or cloth.

Several coastal settlements like Sotkagen-dor (astride Dasht River, north of Jiwani), Sokhta Koh (astride Shadi River, north of Pasni), and Balakot (near Sonmiani) in Pakistan along with Lothal in western India, testify to their role as Harappan trading outposts. Shallow harbours located at the estuaries of rivers opening into the sea allowed brisk maritime trade with Mesopotamian cities.

Austronesian maritime trade network

The first true maritime trade network in the Indian Ocean was by the Austronesian peoples of Island Southeast Asia,[5] who built the first ocean-going ships.[6] They established trade routes with Southern India and Sri Lanka as early as 1500 BC, ushering an exchange of material culture (like catamarans, outrigger boats, lashed-lug and sewn-plank boats, and paan) and cultigens (like coconuts, sandalwood, bananas, and sugarcane); as well as connecting the material cultures of India and China. Indonesians, in particular were trading in spices (mainly cinnamon and cassia) with East Africa using catamaran and outrigger boats and sailing with the help of the Westerlies in the Indian Ocean. This trade network expanded to reach as far as Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, resulting in the Austronesian colonization of Madagascar by the first half of the first millennium AD. It continued up to historic times, later becoming the Maritime Silk Road.[5][7][8][9][10]

Hellenic period

Prior to Roman expansion, the various peoples of the subcontinent had established strong maritime trade with other countries. The dramatic increase in South Asian ports, however, did not occur until the opening of the Red Sea by the Greeks and the Romans and the attainment of geographical knowledge concerning the region's seasonal monsoons. In fact, the first two centuries of the Common Era indicate this increase in trade between present-day western India and Rome. This expansion of trade was due to the comparative peace established by the Roman Empire during the time of Augustus (9 September 61 BC – 19 August AD 14), which allowed for new explorations.

Roman period

The replacement of Greece by the Roman empire as the administrator of the Mediterranean basin led to the strengthening of direct maritime trade with the east and the elimination of the taxes extracted previously by the middlemen of various land-based trading routes.[11] Strabo's mention of the vast increase in trade following the Roman annexation of Egypt indicates that monsoon was known and manipulated for trade in his time.[12]

The trade started by Eudoxus of Cyzicus in 130 BCE kept increasing, and according to Strabo (II.5.12.), writing some 150 years later:[13]

At any rate, when Gallus was prefect of Egypt, I accompanied him and ascended the Nile as far as Syene and the frontiers of Kingdom of Aksum (Ethiopia), and I learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing from Myos Hormos to the subcontinent, whereas formerly, under the Ptolemies, only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise.

— Strabo

By the time of Augustus up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos to India.[13] So much gold was used for this trade, and apparently recycled by the Kushan Empire (Kushans) for their own coinage, that Pliny the Elder (NH VI.101) complained about the drain of specie to India:[14]

Roman ports

The three main Roman ports involved with eastern trade were Arsinoe, Berenice and Myos Hormos. Arsinoe was one of the early trading centers but was soon overshadowed by the more easily accessible Myos Hormos and Berenice.

Arsinoe

The Ptolemaic dynasty exploited the strategic position of Alexandria to secure trade with the subcontinent.[15] The course of trade with the east then seems to have been first through the harbor of Arsinoe, the present day Suez.[15] The goods from the East African trade were landed at one of the three main Roman ports, Arsinoe, Berenice or Myos Hormos.[16] The Romans repaired and cleared out the silted up canal from the Nile to harbor center of Arsinoe on the Red Sea.[17] This was one of the many efforts the Roman administration had to undertake to divert as much of the trade to the maritime routes as possible.[17]

Arsinoe was eventually overshadowed by the rising prominence of Myos Hormos.[17] The navigation to the northern ports, such as Arsinoe-Clysma, became difficult in comparison to Myos Hormos due to the northern winds in the Gulf of Suez.[18] Venturing to these northern ports presented additional difficulties such as shoals, reefs and treacherous currents.[18]

Myos Hormos and Berenice

Myos Hormos and Berenice appear to have been important ancient trading ports, possibly used by the Pharaonic traders of ancient Egypt and the Ptolemaic dynasty before falling into Roman control.[19]

The site of Berenice, since its discovery by Belzoni (1818), has been equated with the ruins near Ras Banas in Southern Egypt.[19] However, the precise location of Myos Hormos is disputed with the latig Abu Sha'ar and the accounts given in classical literature and satellite images indicating a probable identification with Quseir el-Quadim at the end of a fortified road from Koptos on the Nile.[19] The Quseir el-Quadim site has further been associated with Myos Hormos following the excavations at el-Zerqa, halfway along the route, which have revealed ostraca leading to the conclusion that the port at the end of this road may have been Myos Hormos.[19]

Major regional ports

The regional ports of Barbaricum (modern Karachi), Sounagoura (central Bangladesh) Barygaza, Muziris in Kerala, Korkai, Kaveripattinam and Arikamedu on the southern tip of present-day India were the main centers of this trade, along with Kodumanal, an inland city. The Periplus Maris Erythraei describes Greco-Roman merchants selling in Barbaricum "thin clothing, figured linens, topaz, coral, storax, frankincense, vessels of glass, silver and gold plate, and a little wine" in exchange for "costus, bdellium, lycium, nard, turquoise, lapis lazuli, Seric skins, cotton cloth, silk yarn, and indigo".[20] In Barygaza, they would buy wheat, rice, sesame oil, cotton and cloth.[20]

Barigaza

Trade with Barigaza, under the control of the Indo-Scythian Western Satrap Nahapana ("Nambanus"), was especially flourishing:[20]

There are imported into this market-town (Barigaza), wine, Italian preferred, also Laodicean and Arabian; copper, tin, and lead; coral and topaz; thin clothing and inferior sorts of all kinds; bright-colored girdles a cubit wide; storax, sweet clover, flint glass, realgar, antimony, gold and silver coin, on which there is a profit when exchanged for the money of the country; and ointment, but not very costly and not much. And for the King there are brought into those places very costly vessels of silver, singing boys, beautiful maidens for the harem, fine wines, thin clothing of the finest weaves, and the choicest ointments. There are exported from these places spikenard, costus, bdellium, ivory, agate and carnelian, lycium, cotton cloth of all kinds, silk cloth, mallow cloth, yarn, long pepper and such other things as are brought here from the various market-towns. Those bound for this market-town from Egypt make the voyage favorably about the month of July, that is Epiphi.

— Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (paragraph 49).

Muziris

Muziris is a lost port city on the south-western coast of India which was a major center of trade in the ancient Tamil land between the Chera kingdom and the Roman Empire.[21] Its location is generally identified with modern-day Cranganore (central Kerala).[22][23] Large hoards of coins and innumerable shards of amphorae found at the town of Pattanam (near Cranganore) have elicited recent archeological interest in finding a probable location of this port city.[21]

According to the Periplus, numerous Greek seamen managed an intense trade with Muziris:[20]

Then come Naura and Tyndis, the first markets of Damirica (Limyrike), and then Muziris and Nelcynda, which are now of leading importance. Tyndis is of the Kingdom of Cerobothra; it is a village in plain sight by the sea. Muziris, of the same Kingdom, abounds in ships sent there with cargoes from Arabia, and by the Greeks; it is located on a river, distant from Tyndis by river and sea five hundred stadia, and up the river from the shore twenty stadia"

— The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (53–54)

Arikamedu

The Periplus Maris Erythraei mentions a marketplace named Poduke (ch. 60), which G.W.B. Huntingford identified as possibly being Arikamedu in Tamil Nadu, a centre of early Chola trade (now part of Ariyankuppam), about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from the modern Pondicherry.[24] Huntingford further notes that Roman pottery was found at Arikamedu in 1937, and archeological excavations between 1944 and 1949 showed that it was "a trading station to which goods of Roman manufacture were imported during the first half of the 1st century AD".[24]

Decline and legacy

Following the Roman-Persian Wars, the areas under the Roman Byzantine Empire were captured by Khosrow II of the Persian Sassanian Dynasty,[25] but the Byzantine emperor Heraclius reconquered them (628). The Arabs, led by 'Amr ibn al-'As, crossed into Egypt in late 639 or early 640 CE.[26] This advance marked the beginning of the Islamic conquest of Egypt[26] and the fall of ports such as Alexandria,[27] used to secure trade with the subcontinent by the Roman world since the Ptolemaic dynasty.[15]

The decline in trade saw the ancient Tamil country turn to Southeast Asia for international trade, where it influenced the native culture to a greater degree than the impressions made on Rome.[28]

Greater India Hindu-Buddhist period

The Satavahanas developed shipping ventures in Southeast Asia.

The 8th century depiction of a wooden double outrigger and sailed Borobudur ship in ancient Java suggests that there were ancient trading links across the Indian Ocean between Indonesia and Madagascar and East Africa sometimes referred to as the 'Cinnamon Route.' The single or double outrigger is a typical feature of vessels of the seafaring Austronesians and the most likely vessel used for their voyages and exploration across Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Indian Ocean.[29] During this period, between 7th to 13th century in Indonesian archipelago flourished the Srivijaya thalassocracy empire that rule the maritime trade network in maritime Southeast Asia and connecting India and China.

Chinese travels

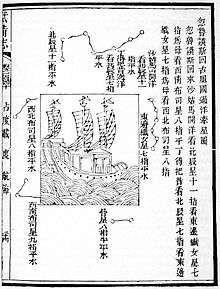

Chinese fleets under Zheng He crisscrossed the Indian Ocean during the early part of the 15th century. The missions were diplomatic rather than commercial, but many exchanges of gift and produces were made.

Japanese trade

During the 16th and 17th century, Japanese ships also made forays into Indian Ocean trade through the Red Seal ship system.

Muslim period

During the Muslim period, in which the Muslims had dominated the trade across the Indian Ocean, the Gujaratis were bringing spices from the Moluccas as well as silk from China, in exchange for manufactured items such as textiles, and then selling them to the Egyptians and Arabs.[30] Calicut was the center of Indian pepper exports to the Red Sea and Europe at this time[30] with Egyptian and Arab traders being particularly active.[30]

In Madagascar, merchants and slave traders from the Middle East (Shirazi Persians, Omani Arabs, Arabized Jews, accompanied by Bantus from southeast Africa) and from Asia (Gujaratis, Malays, Javanese, Bugis) were sometimes integrated within the indigenous Malagasy clans [31][32] New waves of Austronesian migrants arrived in Madagascar at this time leaving behind a lasting cultural and genetic legacy.[33]

European colonial exploration period

Portuguese period

The Portuguese under Vasco da Gama discovered a naval route to the Indian Ocean through the southern tip of Africa in 1497–98. Initially, the Portuguese were mainly active in Calicut, but the northern region of Gujarat was even more important for trade, and an essential intermediary in east–west trade.[30]

Venetian interests were directly threatened as the traditional trade patterns were eliminated and the Portuguese became able to undersell the Venetians in the spice trade in Europe. Venice broke diplomatic relations with Portugal and started to look at ways to counter its intervention in the Indian Ocean, sending an ambassador to the Egyptian court.[34] Venice negotiated for Egyptian tariffs to be lowered to facilitate competition with the Portuguese, and suggested that "rapid and secret remedies" be taken against the Portuguese.[34] The Mamluks sent a fleet in 1507 under Amir Husain Al-Kurdi, which would fight in the Battle of Chaul.[34]

The Ottomans tried to challenge Portugal's hegemony in the Persian Gulf region by sending an armada against the Portuguese under Ali Bey in 1581. They were supported in this endeavor by the chiefs of several local principalities and port towns such as Muscat, Gwadar, and Pasni. However, the Portuguese successfully intercepted and destroyed the Ottoman Armada. Subsequently, the Portuguese attacked Gwadar and Pasni on the Mekran Coast and sacked them in retaliation for providing aid and comfort to the enemy.

Dutch and English period

During the 16th century the Portuguese had established bases in the Persian Gulf. In 1602, the Iranian army under the command of Imam-Quli Khan Undiladze managed to expel the Portuguese from Bahrain. In 1622, with the help of four English ships, Abbas retook Hormuz from the Portuguese in the capture of Ormuz. He replaced it as a trading centre with a new port, Bandar Abbas, nearby on the mainland, but it never became as successful.

See also

- Indian Maritime History

- Winds in the Age of Sail

- Indianization of Southeast Asia

- Indianised kingdom

- Greater India

- Indosphere

- Indian diaspora

- History of Indian influence on Southeast Asia

- Ancient maritime history

References

- CrashCourse (24 May 2012), Int'l Commerce, Snorkeling Camels, and The Indian Ocean Trade: Crash Course World History #18, retrieved 10 July 2019

- "The Monsoon Marketplace. Influences on Southeast Asia, Monsoons, Sea Trade important, Control of Malacca Strait, and Sunda Strait; Money and Power". slideplayer.com. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Gonzaga, Fernando (2014). Monsoon Marketplace: Inscriptions and Trajectories of Consumer Capitalism and Urban Modernity in Singapore and Manila (Thesis). UC Berkeley.

- Neyland, R. S. (1992). "The seagoing vessels on Dilmun seals". In Keith, D.H.; Carrell T.L. (eds.). Underwater archaeology proceedings of the Society for Historical Archaeology Conference at Kingston, Jamaica 1992. Tucson, AZ: Society for Historical Archaeology. pp. 68–74.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN 9783319338224.

- Meacham, Steve (11 December 2008). "Austronesians were first to sail the seas". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- Doran, Edwin, Jr. (1974). "Outrigger Ages". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 83 (2): 130–140.

- Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts (PDF). One World Archaeology. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 0415100542.

- Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961070.

- Blench, Roger (2004). "Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 24 (The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50.

- Lach 1994: 13

- Young 2001: 20

- "The Geography of Strabo published in Vol. I of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1917".

- "minimaque computatione miliens centena milia sestertium annis omnibus India et Seres et paeninsula illa imperio nostro adimunt: tanti nobis deliciae et feminae constant. quota enim portio ex illis ad deos, quaeso, iam vel ad inferos pertinet?" Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.

- Lindsay 2006: 101

- O'Leary 2001: 72

- Fayle 2006: 52

- Freeman 2003: 72

- Shaw 2003: 426

- Halsall, Paul. "Ancient History Sourcebook: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century". Fordham University.

- "Search for India's ancient city". BBC. 11 June 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- George Menachery, Kodungallur City of St. Thomas,Azhikode,1987alias Kodungallur Cradle of Christianity in India, 2000

- http://www.telegraphindia.com/1090803/jsp/frontpage/story_11313800.jsp

- Huntingford 1980: 119.

- Farrokh 2007: 252

- Meri 2006: 224

- Holl 2003: 9

- Kulke 2004: 106

- Borobudur Ship Expedition

- Foundations of the Portuguese empire, hi lo millo1415–1580 Bailey Wallys Diffie p.234ff

- Larson, 2000

- Larson, Pier M. (2000). History and Memory in the Age of Enslavement. Becoming Merina in Highland Madagascar, 1770–1822. Social History of Africa Series. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Heinemann, 414 p. ISBN 0-325-00217-7.

- Lawler. "Ancient crop remains record epic migration to Madagascar". Science: 30 May 2016

- Foundations of the Portuguese empire, 1415–1580 Bailey Wallys Diffie p.230ff