Inhabitants of Saaremaa

Inhabitants of Saaremaa (Latin: Oesel, Osilia, Swedish: Ösel, Danish: Øsel, Finnish: Saarenmaa), refers to people historically living on the island of Saaremaa, an island in Estonia in the Baltic Sea. In modern Estonian, they are called saarlased[1] (Estonian pronunciation: [ˈsɑːrlɑset] "islanders"; singular: saarlane). In Viking-Age literature, the inhabitants were often included under the name "Vikings from Estonia". The name Oeselians was first used by Henry of Livonia in the 13th century. The inhabitants are often mentioned in the historic written sources during the Estonian Viking Age.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Estonia |

|

|

|

Medieval Estonia

|

|

Modern Estonia

|

| Chronology |

|

|

On the eve of Northern Crusades, the inhabitants of Saaremaa were summarized in the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle thus: "The Oeselians, neighbors to the Kurs (Curonians), are surrounded by the sea and never fear strong armies as their strength is in their ships. In summers when they can travel across the sea they oppress the surrounding lands by raiding both Christians and pagans."[2]

Battles and raids

The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia describes a fleet of sixteen ships and five hundred Oeselians ravaging the area that is now southern Sweden, then belonging to Denmark. In the XIVth book of Gesta Danorum, Saxo Grammaticus describes a battle on Öland in 1170 in which the Danish king Valdemar I mobilised his entire fleet to curb the incursions of Couronian and Estonian pirates.

The Livonian Chronicle describes the Oeselians as using two kinds of ships, the piratica and the liburna. The former was a warship, the latter mainly a merchant ship. A piratica could carry approximately 30 men and had a high prow shaped like a dragon or a snakehead as well as a quadrangular sail.

Religion and mythology

The superior god of Oeselians as described by Henry of Livonia was called Tharapita. According to the legend in the chronicle Tharapita was born on a forested mountain in Virumaa (Latin: Vironia), mainland Estonia from where he flew to Oesel, Saaremaa.[3] The name Taarapita has been interpreted as "Taara, help!" (Taara a(v)ita in Estonian) or "Taara keeper" (Taara pidaja). Taara is associated with the Scandinavian god Thor. The story of Tharapita's or Taara's flight from Vironia to Saaremaa has been associated with a major meteor disaster estimated to have happened in 660 ± 85 B.C. that formed Kaali crater in Saaremaa.

Language

Henry of Livonia wrote about an encounter between the Oeselian pagans and a captured Christian missionary, Frederick of Zelle, during the 13th century. The Oeselians are quoted using the words "Laula! Laula! Pappi!" when torturing the missionary.[4] This Finnic[5] expression has been suggested to support the identification of Oeselians as a Finnic language group at that time.[6]

Conquest of Saaremaa

In 1206, the Danish army led by king Valdemar II and Andreas, the Bishop of Lund landed on Saaremaa and attempted to establish a stronghold without success. In 1216 the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the bishop Theodorich joined forces and invaded Saaremaa over the frozen sea. In return the Oeselians raided the territories in Latvia that were under German rule the following spring. In 1220, the Swedish army led by king John I of Sweden and the bishop Karl of Linköping conquered Lihula in Rotalia in Western Estonia. Oeselians attacked the Swedish stronghold the same year, conquered it and killed the entire Swedish garrison including the Bishop of Linköping.

In 1222, the Danish king Valdemar II attempted the second conquest of Saaremaa, this time establishing a stone fortress housing a strong garrison. The Danish stronghold was besieged and surrendered within five days, the Danish garrison returned to Reval, leaving bishop Albert of Riga' brother Theodoric and few others behind hostages as pledges for peace. The castle was leveled to the ground by Oeselians.[7]

In 1227, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, and Bishop Albert of Livonia organized a combined attack against Saaremaa.[8] After the destruction of Muhu Stronghold and surrender of Valjala Stronghold, the Oeselians formally accepted Christianity.[9]

In 1236, after the defeat of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword in the Battle of Saule, military action on Saaremaa broke out again.

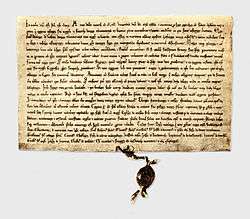

Oeselians accepted Christianity again by signing treaties with the Livonian Order's Master Andreas de Velven and the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek in 1241, setting penalties for pagan rituals.[10] The next treaty was signed in 1255 by the Master of the Order, Anno Sangerhausenn, and, on behalf of the Oeselians, by elders whose "names" (or declaration?) had been phonetically transcribed by Latin scribes as Ylle, Culle, Enu, Muntelene, Tappete, Yalde, Melete, and Cake.[11] The treaty granted several extraordinary rights to the Oeselians. The 1255 treaty included unique clauses concerning the ownership and inheritance of land, the social system, and exemption from certain restrictive religious observances.

In 1261, warfare continued as the Oeselians had again renounced Christianity and killed all the Germans on the island. A peace treaty was signed after the united forces of the Livonian Order, the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek, the forces of Danish Estonia including mainland Estonians and Latvians defeated the Oeselians by conquering the Kaarma stronghold. Soon thereafter, the Livonian Order established a stone fort at Pöide.

On 24 July 1343, during St. George's Night Uprising, the Oeselians killed all the Germans on the island, drowned all the clerics and started to besiege the Livonian Order's castle at Pöide. The Oeselians levelled the castle and killed all the defenders. In February 1344, Burchard von Dreileben led a campaign over the frozen sea to Saaremaa. The Oeselians' stronghold was conquered and their leader Vesse was hanged. In the early spring of 1345, the next campaign of the Livonian Order took place that ended with a treaty mentioned in the Chronicle of Hermann von Wartberge and the Novgorod First Chronicle. Saaremaa remained the vassal of the master of the Livonian Order, and the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek. In 1559, after the fall of the Livonian order in Livonian War, the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek sold Saaremaa to Frederick II of Denmark, who resigned the lands to his brother Duke Magnus of Holstein until the island was taken back to the direct administration of Denmark and in 1645 became a part of Sweden by the Treaty of Brömsebro.

References

- Vesilind, Priit J. (May 2000). "IN SEARCH OF VIKINGS". National Geographic. 197 (5). ISSN 0027-9358.

For centuries Swedish raiders pillaged along the Baltic's eastern shores, but there they faced rivals such as the Kurs and the piratical Saarlased, or Oeselians, from the Estonian island of Saaremaa. Saaremaa's current coat of arms pictures a longboat, and Viking images thrive in Latvian and Estonian legends, jewelry, and folk dress. "Saarlased were the Vikings of the Baltics," said Bruno Pao, a marine historian on Saaremaa. "We have found stone ship settings, burial mounds, silver hoards. The pagan era here lasted until the 13th century."

- The Baltic Crusade By William L. Urban; p. 20 ISBN 0-929700-10-4

- The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia, Page 193 ISBN 0-231-12889-4

- Tamm et. al. (eds.). "Crusading and chronicle writing on the medieval Baltic frontier". Routledge. p. 125. Retrieved 5 October 2018.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Folklore Studies / Dept. of Philosophy, History, Culture and Art Studies, University of Helsinki, Helsinki. "De situ linguarum fennicarum aetatis ferreae, Pars I". Retrieved 5 October 2018.

Henry’s chronicle includes quotations ascribed to the Oeselians, such as Laula! Laula, pappi! [‘Sing! Sing, priest!’] (HCL XVIII.8). The expression is unambiguously Finnic and supports the identification of Oeselians as a Finnic language group. This is further corroborated by the Finnic toponymy that does not seem to include substantial earlier substrate layers (at least in the light of research today; cf. Kallasmaa 1996–2000)

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The Baltic Crusade By William L. Urban; p 113-114 ISBN 0-929700-10-4

- 1227. (2018). In Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson chronology of world history. Abington, UK: Helicon.

- Roston, Anne (15 Aug 1993). "A Newly Opened Estonian Island". New York: The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

In the early 13th century, the residents of Oesel, as Saaremaa was then known, were notorious for pirating Baltic churches. They were, indeed, the very last pagan holdouts in the region; by the year 1227, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, crusaders who originated in Germany, had forced every other tribe and town in what now are Estonia and Latvia to submit to baptism or the sword. On Jan. 6, 1227, a huge army of crusading Germans, Rigans, Letts and Estonians gathered on the mainland parallel to Oesel. They and their horses marched across the frozen Baltic to the tiny island of Mona, attached by causeway to Oesel's northeastern tip. Deprived of a maritime defense, the Oeselians were finally forced to succumb.

- Forey, A.J. 1993, "Military Orders and Secular Warfare in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries", Viator, vol. 24, pp. 79-100. (page 99 cited)

- Liv-, est- und kurländisches Urkundenbuch: Nebst Regesten