Lithuanian folk music

Lithuanian folk music belongs to Baltic music branch which is connected with neolithic corded ware culture. In Lithuanian territory meets two musical cultures: stringed (kanklių) and wind instrument cultures. These instrumental cultures probably formed vocal traditions. Lithuanian folk music is archaic, mostly used for ritual purposes, containing elements of paganism faith.

Vocal music

There are three ancient styles of singing in Lithuania connected with ethnographical regions: monophony, multi-voiced homophony, heterophony and polyphony. Monophony mostly occurs in southern (Dzūkija), southwest (Suvalkija) and eastern (Aukštaitija) parts of Lithuania. Multi-voiced homophony, widespread in entire Lithuania, is the most archaic in Samogitia. Traditional vocal music is held in high esteem on a world scale: Lithuanian song fests and sutartinės multipart songs are on the UNESCO's representative list of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Sutartinės (multipart songs)

Sutartinės (from the word sutarti—to be in concordance, in agreement, singular sutartinė) are highly unique examples of folk music. They are an ancient form of two and three voiced polyphony, based on the oldest principles of multivoiced vocal music: heterophony, parallelism, canon, hocket, and free imitation. Most of the sutartinės' repertoire was recorded in the 19th and 20th centuries, but sources from the 16th century on show that they were significant along with monophonic songs. At present the sutartinės have almost become extinct as a genre among the population, but they are fostered by many Lithuanian folklore ensembles.

The topics and functions of sutartinės encompass all major Lithuanian folk song genres. Melodies of sutartinės are not complex, containing two to five pitches. The melodies are symmetrical, consisting of two equal-length parts; rhythms are typically syncopated, and the distinctly articulated refrains give them a driving quality.

Sutartinės can be classed into three groups according to performance practices and function:

- Dvejinės (“twosomes”) are sung by two singers or two groups of singers.

- Trejinės (“threesomes”) are performed by three singers in strict canon.

- Keturinės (“foursomes") are sung by two pairs of singers.

Sutartinės are a localized phenomenon, found in the northwestern part of Lithuania. They were sung by women, but men performed instrumental versions on the kanklės (psaltery), on horns, and on the skudučiai (pan-pipes). The rich and thematically varied poetry of the sutartinės attests to their importance in the social fabric. Sutartinės were sung at festivals, gatherings, weddings, and while performing various chores. The poetic language while not being complex is very visual, expressive and sonorous. The rhythms are clear and accented. Dance sutartinės are humorous and spirited, despite the fact that the movements of the dance are quite reserved and slow. One of the most important characteristics of the sutartinės is the wide variety of vocables used in the refrains (sodauto, lylio, ratilio, tonarilio, dauno, kadujo, čiūto, etc.).

Wedding songs

Different vocal and instrumental forms developed, such as lyrical, satirical, drinking and banqueting songs, musical dialogues, wedding laments, games, dances and marches. From an artistic standpoint the lyric songs are the most interesting. They reflect the entirety of the bride's life: her touching farewells to loved ones as she departs for the wedding ceremony or her husband's home, premonitions about the future, age-old questions about relationships between the mother-in-law and daughter-in-law, and the innermost thoughts and emotions of the would-be bride.

War-historical time songs

Chronicles and historical documents of the 13th through 16th centuries contain the first sources about songs relating the heroics of those fallen in battle against the Teutonic Knights. Later songs mention the Swedes, there are frequent references to Riga and Battle of Kircholm; songs collected in the early 19th century mention battles with the Tatars. Songs from uprisings and revolutions, as well as anti-Soviet guerrilla resistance in 1945-1952 and deportation songs are also classified as wartime historical songs.

Calendar cycle and ritual songs

They were sung at prescribed times of the year while performing the appropriate rituals. There are songs of Shrovetide and Lent, Easter swinging songs, and Easter songs called lalavimai. The Advent songs reflect the mood of staidness and reflection. Christmas songs contain vocables such as kalėda, lėliu kalėda; oi kalėda kalėdzieka, while Advent songs contain vocables such as leliumoj, aleliuma, aleliuma rūta, aleliuma loda and others. There are several typical melodic characteristics associated with Christmas ritual songs, such as a narrow range, three-measure phrases, dance rhythms, a controlled slow tempo, and a tonal structure based on phrygian, mixolydian or aeolian tetrachords. Polyphonic St. John's Feast songs are commonly called kupolinės, which include refrains and vocables such as kupolėle kupolio, kupolio kupolėlio, or kupole rože.

Work songs

Work songs vary greatly in function and age. There are some very old examples, which have retained their direct relation with the rhythm and process of the work to be done. Later work songs sing more of a person's feelings, experiences and aspirations. The older work songs more accurately relate the various stages of the work to be done. They are categorized according to their purpose on the farm, in the home, and so on.

- Herding songs. Shepherd songs are sung by children, while nightherding songs are sung by adults. The shepherding songs reflect the actual tending of animals, the social situation of children, as well as references to ancient beliefs. The raliavimai or warbles are also recitative type melodies, distinguished by the vocable ralio, which is meant to calm the animals. The raliavimai have no set poetic or musical form being free recitatives, unified by the refrains. Some warbles end in a prolonged ululation, based on a major or minor third.

- Haymaking songs. Refrains are common in haymaking songs. The most common vocable used is valio, hence — valiavimas, the term for the singing of haymaking songs. The vocable is sung slowly and broadly, evoking the spacious fields and the mood of the haymaking season. The melodies of earlier origin are similar to other early work songs while more modern haymaking songs have a wider modal range and are structurally more complex. Most are in major and are homophonic.

- Rye harvesting songs. The harvesting of rye is the central stage in the agricultural cycle. The mood is doleful and sad, love and marriage are the prevailing topics in them. Family relationships between parents and children are often discussed, with special emphasis on the hard lot of the daughter-in law in a patriarchal family. Rye harvesting songs have rhythmic and tonal structures in common, which attests to their antiquity. Their unique melodic style is determined by close connection to ritual and the function of the work. The modal-tonal structure of some of these songs revolves around a minor third, while others are built on a major tetrachord.

- Oat harvesting, flax and buckwheat pulling and hemp gathering songs. Oat harvesting songs sing of the lad and the maid, of love and marriage as well as the work process: sowing, harrowing, cultivating, reaping, binding, stacking, transporting, threshing, milling, and even eating. In addition to the monophonic oat harvesting songs of Dzūkija, there are quite a few sutartinės from northern Aukštaitija, which are directly related to the job of growing oats.

- Milling songs. The genre can be identified by characteristic refrains and vocables, such as zizui malui, or malu malu. They suggest the hum of the millstones as well as the rhythm of the milling. Milling was done by women, and the lyrics are about women's life and family relationships, as well as the work itself. Milling songs are slow tempo, composed, the melodic rhythm varies little.

- Spinning and weaving songs. In spinning songs the main topic is the spinning itself, the spinner, and the spinning wheel while weaving songs mention the weaving process, the weaver, the loom, the delicate linens. Some spinning songs are cheerful and humorous, while others resemble the milling songs which bemoan the woman's hard lot and longing for their homes and parents. The texts describe the work process, while the refrains mimic the whirring of the spinning wheel. There are also highly unique spinning sutartinės, typified by clear and strict rhythms.

- Laundering songs. Sometimes the refrain imitates the sounds of the beetle and mangle — the laundering tools. The songs often hyperbolyze images of the mother-in-law's outlandish demands, such as using the sea instead of a beetle, and the sky in place of a mangle, and the treetops for drying.

- Fishing and hunting songs. Fishing songs are about the sea, the bay, the fisherman, his boat, the net, and they often mention seaside place names, such as Klaipėda or Rusnė. The emotions of young people in love are often portrayed in ways that are unique only to fishing songs. The monophonic melodies are typical of singing traditions of the seaside regions of Lithuania. Hunting motifs are very clearly expressed in hunting songs.

- Berry picking and mushroom gathering songs. These are singular songs. Berry picking songs describe young girls picking berries, meeting boys and their conversations. Mushroom gathering songs can be humorous, making light of the process of gathering and cooking the mushrooms, describing the "war" of the mushrooms or their "weddings."

Instrumental music

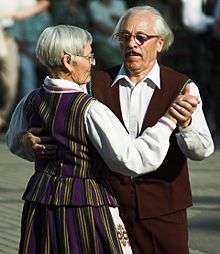

The rateliai round dances have long been a very important part of Lithuanian folk culture, traditionally performed without instrumental accompaniment. Since the 19th century, however, fiddle, basetle, lamzdeliai and kanklės came to accompany the dances, while modern groups also incorporate bandoneon, accordion, concertina, mandolin, clarinet, cornet, guitar and harmonica. During the Soviet era, dance ensembles used box kanklės and a modified clarinet called the birbynės; although the Soviet ensembles were ostensibly folk-based, they were modernized and sanitized and used harmonized and denatured forms of traditional styles.[1]

The most important Lithuanian popular folk music ensembles included Skriaudžių kanklės, formed in 1906, and Lietuva. Such ensembles were based on traditional music, but were modernized to be palatable to the masses; the early 20th century also saw the spread of traditional musical plays like The Kupiškėnai Wedding.[1]

Some of the most prominent modern village ensembles: Marcinkonys (Varėna dst.), Žiūrai (Varėna dst.), Kalviai-Lieponys (Trakai dst.), Luokė (Telšiai dst.), Linkava (Linkuva, Pakruojis dst.), Šeduviai (Šeduva, Radviliškis dst.), Užušiliai (Biržai dst.), Lazdiniai-Adutiškis (Švenčionys dst.). Some of the most prominent town folklore groups: Ratilio, Ūla, Jievaras, Poringė (Vilnius), Kupolė (Kaunas), Verpeta (Kaišiadorys), Mėguva (Palanga), Insula (Telšiai), Gastauta (Rokiškis), Kupkiemis (Kupiškis), Levindra (Utena), Sūduviai (Vilkaviškis). Children folk groups: Čiučiuruks (Telšiai), Kukutis (Molėtai), Čirulis (Rokiškis), Antazavė (Zarasai dst.).

Instruments

Wind instruments :

- birbynė

- daudytės

- jaučio ragas

- kerdžiaus trimitas

- lumzdelis

- medžioklės ragas

- molinukas

- ožragis

- ragai and nagai

Kankles

Kankles - sekminių ragelis

- skudučiai

- švilpas

- švilpukas

- tošelė

- ubikas

- vilioklis

- žievės trimitas

String instruments :

- cimbolai

- kanklės

- pūslinė

- smuikas

Percussion :

- būgnas

- būgnelis or bandurelis

- dzingulis

- kleketas

- šaukštai

- skrabalai

- tabalas

- terkšlė

- tošelė

References

- Cronshaw, pgs. 22 – 23