Baltic states

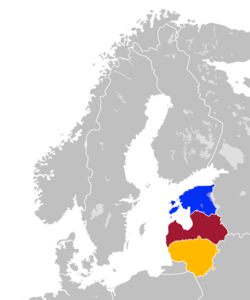

The Baltic states (Estonian: Balti riigid, Baltimaad; Latvian: Baltijas valstis; Lithuanian: Baltijos valstybės), also known as the Baltic countries, Baltic republics, Baltic nations, Baltic kingdom, or simply the Baltics, is a geopolitical term, typically used to group the three sovereign states in Northern Europe on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The term is not used in the context of cultural areas, national identity, or language, because while the majority of people in Latvia and Lithuania are Baltic people, the majority in Estonia are Finnic. The three countries do not form an official union, but engage in intergovernmental and parliamentary cooperation.[1] The most important areas of cooperation between the three countries are foreign and security policy, defence, energy, and transportation.[2]

| Baltic states | |

|---|---|

| |

| Countries | |

| Time zones | UTC+02:00 |

All three countries are members of NATO, the eurozone, the OECD, and the European Union. In 2020 and 2021, Estonia is also a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. All three are classified as high-income economies by the World Bank and maintain a very high Human Development Index.[3]

Etymology

_(14793687963).jpg)

The term Baltic stems from the name of the Baltic Sea – a hydronym dating back to the 3rd century B.C. (Erastothenes mentioned Baltia in Ancient Greek) and earlier.[4] Although there are several theories about its origin, most ultimately trace it to the Indo-European root *bhel[5] meaning 'white, fair'. This meaning is retained in modern Baltic languages, where baltas in Lithuanian and balts in Latvian mean 'white'.[6] However, the modern names of the region and the sea that originate from this root, were not used in either of the two languages prior to the 19th century.[7]

Since the Middle Ages, the Baltic Sea has appeared on maps in Germanic languages as the equivalent of 'East Sea': German: Ostsee, Danish: Østersøen, Dutch: Oostzee, Swedish: Östersjön, etc. Indeed, the Baltic Sea lies mostly to the east of Germany, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. The term was also used historically to refer to Baltic Dominions of the Swedish Empire (Swedish: Östersjöprovinserna) and, subsequently, the Baltic governorates of the Russian Empire (Russian: Остзейские губернии, romanized: Ostzejskie gubernii).[7] Terms related to modern name Baltic appear in ancient texts, but had fallen into disuse until reappearing as the adjective Baltisch in German, from which it was adopted in other languages.[8] During the 19th century, Baltic started to supersede Ostsee as the name for the region. Officially, its Russian equivalent Прибалтийский (Pribaltiyskiy) was first used in 1859.[7] This change was a result of the Baltic German elite adopting terms derived from Baltisch to refer to themselves.[8][9]

The term Baltic states was, until the early 20th century, used in the context of countries neighbouring the Baltic Sea: Sweden and Denmark, sometimes also Germany and the Russian Empire. With the advent of Foreningen Norden (the Nordic Associations), the term was no longer used for Sweden and Denmark.[10][11] After World War I, the new sovereign states that emerged on the east coast of the Baltic Sea – Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and during the Interwar period, Finland – became known as the Baltic states.[8]

History

Summary

Throughout the 18th century to the 20th century, the Baltic states were part of the Russian Empire until the three countries gained independence in 1918 near the end of World War I. They were later occupied and annexed by the Soviet Union and briefly, Nazi Germany during World War II before the Soviets regained control of the Baltic states. Soviet rule ended when the three countries declared the occupation illegal and culminated with the restoration of independence to their pre-war status in 1991 when communism collapsed in Eastern Europe.

Northern Crusades

In the 13th century pagan and Eastern Orthodox Baltic and Finnic peoples in the region became a target of the Northern Crusades.[12][13] In the aftermath of the Livonian crusade, a crusader state officially named Terra Mariana, but also known as Livonia, was established in the territory of modern Latvia and Southern Estonia. It was divided into four autonomous bishoprics and lands of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. After the Brothers of the Sword suffered defeat at the Battle of Saule to Lithuanians, the remaining Brothers were integrated into the Teutonic Order as the autonomous Livonian Order. Northern Estonia initially became a Danish dominion, but it was purchased by the Teutonic Order in the mid-14th century. The majority of the crusaders and clergy were German, and Baltic Germans remained influential in Estonia and most of Latvia until the first half of the 20th century: they formed the backbone of the local gentry, and German served both as a lingua franca and for record-keeping.[8]

The Lithuanians were also targeted by the crusaders; however, they were able to resist and established the Kingdom of Lithuania in 1251 which later became Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It expanded to the east conquering former principalities of Kiev up to the Black sea. After the Union of Krewo in 1385, Grand Duchy of Lithuania created a dynastic union with Kingdom of Poland, they became ever more closely integrated and finally merged into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569. After victory in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, the Polish–Lithuanian union became a major political and military power in the region.

Kingdom and Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Lithuanians were also targeted by the crusaders; however, they were able to defend the country from Livonian and Teutonic Orders and established the Kingdom of Lithuania in 1251 which later, after the death of King Mindaugas became Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Mindaugas was the first Lithuanian ruler who accepted Christianity. During the reign of successors of Mindaugas, Gediminas, and later Kęstutis and Algirdas, followed by Vytautas Grand Duchy of Lithuania expanded to the east conquering former principalities of Kiev up to the Black sea. GDL became one of the most influential powers in Northern and Eastern Europe in 14th–16th century. The intensive wars with Teutonic Order and Muscovy forced Grand Duchy of Lithuania to search for allies. Therefore, at the Union of Krewo in 1385, Grand Duchy of Lithuania created a dynastic union with Kingdom of Poland. In 1387 the Christianization of Lithuania occurred[15] - it signified the official adoption of Christianity by Lithuanians, the last pagan nation in Europe. After the victory of joint Polish - Lithuanian forces in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, the Polish–Lithuanian union became a major political and military power in the region. Growing threat of Muscovy and prolonged Muscovite–Lithuanian Wars forced Lithuania into the union of Lublin 1569 in which Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was created. Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth existed up to 1795 and was partitioned in three stages by the neighboring Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Monarchy.

Baltic Sea dominions of The Swedish Empire

In 1558 Livonia was attacked by the Tsardom of Russia and the Livonian war broke out, lasting until 1583. The rulers of different regions within Livonia sought to ally with foreign powers, which resulted in Polish–Lithuanian, Swedish and Danish involvement. As a result, by 1561 the Livonian confederation had ceased to exist and its lands in modern Latvia and Southern Estonia became the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia and the Duchy of Livonia, which were vassals to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Osel island came under Danish rule and Northern Estonia became the Swedish Duchy of Estonia. In the aftermath of later conflicts of the 17th century, much of the Duchy of Livonia and Osel also came under Swedish control as Swedish Livonia. These newly acquired Swedish territories, as well as Ingria and Kexholm (now the western part of the Leningrad Oblast of Russia), became known as the Baltic Dominions. Parts of the Duchy of Livonia that remained in the Commonwealth became Inflanty Voivodeship, which contributed to the modern Latgale region of Eastern Latvia becoming culturally distinct from the rest of Latvia as the German nobility lost its influence and the region remained Catholic just like Poland-Lithuania, while the rest of Latvia (and also Estonia) became Lutheran.

Baltic governates of Russian Empire

At the beginning of the 18th century the Swedish Empire was attacked by a coalition of several European powers in the Great Northern War. Among these powers was Russia, seeking to restore its access to the Baltic Sea. During the course of the war it conquered all of the Swedish provinces on the Eastern Baltic coast. This acquisition was legalized by the Treaty of Nystad in which the Baltic Dominions were ceded to Russia.[16] The treaty also granted the Baltic-German nobility within Estonia and Livonia the rights to self-government, maintaining their financial system, existing customs border, Lutheran religion, and the German language; this special position in the Russian Empire was reconfirmed by all Russian Tsars from Peter the Great to Alexander II.[17] Initially these were two governorates named after the largest cities: Riga and Reval (now Tallinn). After the Partitions of Poland which took place in the last quarter of the 18th century, the third Ostsee governorate was created, as the Courland Governorate (presently a part of Latvia). This toponym stems from the Curonians, one of the Baltic[18] indigenous tribes. Following the annexation of Courland the two other governates were renamed to the Governorate of Livland and the Governorate of Estland. Russian replaced German as the language of administration e.g. of the cities of Riga and Tallinn in the 1890s.

In the late 19th century, nationalist sentiment grew in Estonia and in Latvia morphing into an aspiration to national statehood after the 1905 Russian Revolution.

Newly independent countries East of the Baltic Sea

After the First World War the term "Baltic states" came to refer to countries by the Baltic Sea that had gained independence from Russia in its aftermath. As such it included not only former Baltic governorates, but also Latgale (Latvia), Lithuania and Finland.[19] As World War I came to a close, Lithuania declared independence and Latvia formed a provisional government. Estonia had already obtained autonomy from tsarist Russia in 1917, but was subsequently occupied by the German Empire; they fought an independence war against Soviet Russia and Baltic nobility before gaining true independence from 1920 to 1939. Latvia and Lithuanians followed a similar process, until the Latvian War of Independence and Lithuanian Wars of Independence were extinguished in 1920.

During the interwar period these countries were sometimes referred to as limitrophe states between the two World Wars, from the French, indicating their collectively forming a rim along Bolshevik Russia's, later the Soviet Union's, western border. They were also part of what Clemenceau considered a strategic cordon sanitaire, the entire territory from Finland in the north to Romania in the south, standing between Western Europe and potential Bolshevik territorial ambitions.[20][21]

Prior to World War II Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania each experienced an authoritarian head of state who had come to power after a bloodless coup: Antanas Smetona in Lithuania (December 1926), Konstantin Päts in Estonia (March 1934), and Kārlis Ulmanis in Latvia (May 1934). Some note that the events in Lithuania differed from its two more northerly neighbors, with Smetona having different motivations as well as securing power 8 years before any such events in Latvia or Estonia took place. Despite considerable political turmoil in Finland no such events took place there. Finland did however get embroiled in a bloody civil war, something that did not happen in the Baltics.[22] Some controversy surrounds the Baltic authoritarian régimes – due to the general stability and rapid economic growth of the period (even if brief), some commenters avoid the label "authoritarian"; others, however, condemn such an "apologetic" attitude, for example in later assessments of Kārlis Ulmanis.

Soviet and German occupations

In accordance with a secret protocol within the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 that divided Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence, the Soviet Army entered eastern Poland in September 1939, and then coerced Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania into mutual assistance treaties which granted them the right to establish military bases in these countries. In June 1940, the Red Army occupied all of the territory of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and installed new, pro-Soviet governments in all three countries. Following elections (in which only pro-communist candidates were allowed to run), the newly elected parliaments of the three countries formally applied to join the Soviet Union in August 1940 and were incorporated into it as the Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republics.

Repressions, executions and mass deportations followed after that in the Baltics.[23][24] The Soviet Union attempted to Sovietize its occupied territories, by means such as deportations and instituting the Russian language as the only working language. Between 1940 and 1953, the Soviet government deported more than 200,000 people from the Baltic to remote locations in the Soviet Union. In addition, at least 75,000 were sent to Gulags. About 10% of the adult Baltic population were deported or sent to labor camps.[25] (See June deportation, Soviet deportations from Estonia, Sovietization of the Baltic states)

The Soviet control of the Baltic states was interrupted by Nazi German invasion of this region in 1941. Initially, many Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians considered the Germans as liberators. The Baltic countries hoped for the restoration of independence, but instead the Germans established a civil administration, known as the Reichskommissariat Ostland. During the occupation the Germans carried out discrimination, mass deportations and mass killings, generating Baltic resistance movements (see German occupation of the Baltic states during World War II).[26] Over 190,000 Lithuanian Jews, nearly 95% of Lithuania's pre-war Jewish community, and 66,000 Latvian Jews were murdered. The German occupation lasted until late 1944 (in Courland, until early 1945), when the countries were reoccupied by the Red Army and Soviet rule was re-established, with the passive agreement of the United States and Britain (see Yalta Conference and Potsdam Agreement).

The forced collectivisation of agriculture began in 1947, and was completed after the mass deportation in March 1949 (see Operation Priboi). Private farms were confiscated, and farmers were made to join the collective farms. In all three countries, Baltic partisans, known colloquially as the Forest Brothers, Latvian national partisans, and Lithuanian partisans, waged unsuccessful guerrilla warfare against the Soviet occupation for the next eight years in a bid to regain their nations' independence. The armed resistance of the anti-Soviet partisans lasted up to 1953. Although the armed resistance was defeated, the population remained anti-Soviet.

Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were considered to be under Soviet occupation by the United States, the United Kingdom,[27] Canada, NATO, and many other countries and international organizations.[28] During the Cold War, Lithuania and Latvia maintained legations in Washington DC, while Estonia had a mission in New York. Each was staffed initially by diplomats from the last governments before USSR occupation.[29]

Restoration of independence

In the late 1980s a massive campaign of civil resistance against Soviet rule, known as the Singing revolution, began. On 23 August 1989, the Baltic Way, a two-million-strong human chain, stretched for 600 km from Tallinn to Vilnius. In the wake of this campaign Gorbachev's government had privately concluded that the departure of the Baltic republics had become "inevitable".[30] This process contributed to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, setting a precedent for the other Soviet republics to secede from the USSR. Soviet Union recognized the independence of three Baltic states on 6 September 1991. Troops were withdrawn from the region (starting from Lithuania) from August 1993. The last Russian troops were withdrawn from there in August 1994.[31] Skrunda-1, the last Russian military radar in the Baltics, officially suspended operations in August 1998.[32]

Current position of the Baltic countries

.jpg)

The Baltic countries are located in Northern Europe, and because each has access to the sea, they are able to interact with many European countries. All three countries are parliamentary democracies, with unicameral parliaments elected by popular vote for four-year terms: Riigikogu in Estonia, Saeima in Latvia and Seimas in Lithuania. In Latvia and Estonia, the president is elected by parliament, while Lithuania has a semi-presidential system whereby the president is elected by popular vote. All are members of the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Each of the three countries has declared itself to be the restoration of the sovereign nation that had existed from 1918 to 1940, emphasizing their contention that Soviet domination over the Baltic nations during the Cold War period had been an illegal occupation and annexation.

The same legal interpretation is shared by the United States, the United Kingdom, and most other Western democracies, who held the forcible incorporation of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania into the Soviet Union to be illegal. At least formally, most Western democracies never considered the three Baltic states to be constituent parts of the Soviet Union. Australia was a brief exception to this support of Baltic independence: in 1974, the Labor government of Australia did recognize Soviet dominion, but this decision was reversed by the next Australian Parliament.[33] Other exceptions included Sweden, which was the first Western country, and one of the very few to ever do so, to recognize the incorporation of the Baltic states into the Soviet Union as lawful.[34]

After the Baltic states had restored their independence, integration with Western Europe became a major strategic goal. In 2002, the Baltic nations applied for membership of NATO and the EU. All three became NATO members on 29 March 2004, and joined the EU on 1 May 2004. The Baltic states are currently the only former Soviet states to have joined either organization.

Regional cooperation

During the Baltic struggle for independence 1989–1992, a personal friendship developed between the (at that time unrecognized) Baltic ministers of foreign affairs and the Nordic ministers of foreign affairs. This friendship led to the creation of the Council of the Baltic Sea States in 1992, and the EuroFaculty in 1993.[35]

Between 1994 and 2004, the BAFTA free trade agreement was established to help prepare the countries for their accession to the EU, rather than out of the Baltic states' desire to trade among themselves. The Baltic countries were more interested in gaining access to the rest of the European market.

Currently, the governments of the Baltic states cooperate in multiple ways, including cooperation among presidents, parliament speakers, heads of government, and foreign ministers. On 8 November 1991, the Baltic Assembly, which includes 15 to 20 MPs from each parliament, was established to facilitate inter-parliamentary cooperation. The Baltic Council of Ministers was established on 13 June 1994 to facilitate intergovernmental cooperation. Since 2003, there is coordination between the two organizations.[36]

Compared with other regional groupings in Europe, such as Nordic council or Visegrad Four, Baltic cooperation is rather limited. Possible explanations include the short history of restored sovereignty and fear of losing it again, along with an orientation toward Nordic countries and Baltic-Nordic cooperation in The Nordic-Baltic Eight. Estonia especially has attempted to construct a Nordic identity for itself and denounced Baltic identity, despite still seeking to preserve close relationship with other countries in the region.[37][38]

All three countries are members of the New Hanseatic League, a group of Northern European countries in the EU formed to advocate a common fiscal position.

Current leaders

Energy security of Baltic states

Usually the concept of energy security is related to the uninterruptible supply, sufficient energy storage, advanced technological development of energy sector and environmental regulations.[39] Other studies add other indicators to this list: diversification of energy suppliers, energy import dependence and vulnerability of political system.[40]

Even now being a part of the European Union, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are still considered as the most vulnerable EU member states in the energy sphere.[41] Due to their Soviet past, Baltic states have several gas pipelines on their territories coming from Russia. Moreover, several routes of oil delivery also have been sustained from Soviet times: These are ports in Ventspils, Butinge and Tallinn.[42] Therefore, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania play a significant role not only in consuming, but also in distribution of Russian energy fuels extracting transaction fees.[42] So, the overall EU dependence on the Russia's energy supplies from the one hand and the need of Baltic states to import energy fuels from their closer hydrocarbon-rich neighbor creates a tension that could jeopardize the energy security of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.[42]

As a part of the EU from 2004, Baltic states must comply with the EU's regulations in energy, environmental and security spheres. One of the most important documents that the EU applied to improve the energy security stance of the Baltic states are European Union climate and energy package, including the Climate and Energy Strategy 2020, that aims to reduce the greenhouse emissions to 20%, increase the energy production from renewables for 20% in overall share and 20% energy efficiency development.[43]

Assessment

The calculations take into account not only economic, but also technological and energy-related factors: Energy and carbon intensity of transport and households, trade balance of total energy, energy import dependency, diversification of energy mix, etc.[39] It was stated that from 2008, Baltic states experiences a positive change in their energy security score. They diversified their oil import suppliers due to shutdown of Druzhba gas pipeline in 2006 and increased the share of renewable sources in total energy production with the help of the EU policies.[39]

Estonia usually was the best performing country in terms of energy security, but new assessment shows that even though Estonia has the highest share of renewables in the energy production, its energy economy has been still characterized by high rates of carbon intensity. Lithuania, in contrast, achieved the best results on carbon intensity of economy but its energy dependence level is still very high. Latvia performed the best according to all indicators. Especially, the high share of renewables were introduced to the energy production of Latvia, that can be explained by the state's geographical location and favorable natural conditions.[39]

Possible threats to energy security

Firstly, there is a major risk of energy supply disruption. Even if there are several electricity interconnectors that connect the area with electricity-rich states (Estonia-Finland interconnector, Lithuania-Poland interconnector, Lithuania-Sweden interconnector), the pipeline supply of natural gas and tanker supply of oil are unreliable without modernization of energy infrastructure.[41]

Secondly, the dependence on single supplier – Russia – is not healthy both for economics and politics.[44] As it was in 2009 during the Russian-Ukrainian gas dispute, when states of Eastern Europe were deprived from access to the natural gas deliveries, the reoccurrence of the situation may again lead to economic, political and social crisis. Therefore, the diversification of suppliers is needed.[41]

Finally, the low technological enhancement results in slow adaptation of new technologies, such as construction and use of renewable sources of energy. This also poses a threat to energy security of the Baltic states, because slows down the renewable energy consumption and lead to low rates of energy efficiency.[41]

Economies

Economically, parallel with the political changes, and the democratic transition, – as a rule of law states – the previous command economies were transformed via the legislation into market economies, and set up or renewed the major macroeconomic factors: budgetary rules, national audit, national currency and central bank. Generally, they shortly encountered the following problems: high inflation, high unemployment, low economic growth and high government debt. The inflation rate, in the examined area, relatively quickly dropped to below 5% by 2000. Meanwhile, these economies were stabilised, and in 2004 all of them joined the European Union. New macroeconomic requirements have arisen for them; the Maastricht criteria became obligatory and later the Stability and Growth Pact set stricter rules through national legislation by implementing the regulations and directives of the Sixpack, because the financial crisis was a shocking milestone.[45]

All three countries are members of the European Union, and the Eurozone. They are classified as high-income economies by the World Bank and maintain high Human Development Index. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are also members of the OECD.[3]

Estonia adopted the euro in January 2011, Latvia in January 2014, and Lithuania in January 2015.

Culture

Ethnic groups

Estonians are Finnic people, together with the neighboring Finns. The Latvians and Lithuanians, linguistically and culturally related to each other, are Baltic and Indo-European people. The peoples in the Baltic states have together inhabited the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea for millennia, although not always peacefully in ancient times, over which period their populations, Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian have remained remarkably stable within the approximate territorial boundaries of the current Baltic states. While separate peoples with their own customs and traditions, historical factors have introduced cultural commonalities across and differences within them.

The population of the Baltic countries belong to different Christian denominations, a reflection of historical circumstances. Both Western and Eastern Christianity had been introduced by the end of the first millennium. The current divide between Lutheranism to the north and Catholicism to the south is the remnant of Swedish and Polish hegemony, respectively, with Orthodox Christianity remaining the dominant faith among Russian and other East Slavic minorities.

The Baltic states have historically been in many different spheres of influence, from Danish over Swedish and Polish–Lithuanian, to German (Hansa and Holy Roman Empire), and before independence in the Russian sphere of influence.

The Baltic states have a considerable Slavic minority: in Latvia: 33.0% (including 25.4% Russian, 3.3% Belarusian, 2.2% Ukrainian, and 2.1% Polish),[46] in Estonia: 27.6%[47] and in Lithuania: 12.2% (including 5.6% Polish and 4.5% Russian).[48]

The Soviet Union conducted a policy of Russification by encouraging Russians and other Russian-speaking ethnic groups of the Soviet Union to settle in the Baltic Republics. Today, ethnic Russian immigrants from the former Soviet Union and their descendants make up a sizable minority in the Baltic states, particularly in Latvia (about one-quarter of the total population and close to one-half in the capital Riga) and Estonia (one-quarter of the population).

Because the three Baltic states had been occupied by Soviet Union later than other territories, there was a strong feeling of national identity (often labeled "bourgeois nationalism" by Soviets) and popular resentment towards the imposed Soviet rule in the three countries, in combination with Soviet cultural policy, which employed superficial multiculturalism (in order for the Soviet Union to appear as a multinational union based on free will of peoples) in limits allowed by the Communist "internationalist" (but in effect pro-Russification) ideology and under tight control of the Communist Party (those of the Baltic nationals who crossed the line were called "bourgeois nationalists" and repressed). This let Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians preserve a high degree of Europe-oriented national identity.[49] In Soviet times this made them appear as the "West" of the Soviet Union in the cultural and political sense, thus as close to emigration a Russian could get without leaving the Soviet Union.

Languages

The languages of Baltic nations belong to two distinct language families. The Latvian and Lithuanian languages belong to the Indo-European language family and are the only extant members of the Baltic language group (or more specifically, Eastern Baltic subgroup of Baltic).

The Estonian language is a Finnic language, together with neighboring Finland's Finnish language.

Apart from the indigenous languages, German was the dominant language in Estonia and Latvia in academics, professional life, and upper society from the 13th century until World War I. Polish served a similar function in Lithuania. Numerous Swedish loanwords have made it into the Estonian language; it was under the Swedish rule that schools were established and education propagated in the 17th century. Swedish remains spoken in Estonia, particularly the Estonian Swedish dialect of the Estonian Swedes of northern Estonia and the islands (though many fled to Sweden as the Soviet Union invaded and re-occupied Estonia in 1944). There is also significant proficiency in Finnish in Estonia owing to its closeness to the native Estonian and also the widespread practice of listening to Finnish broadcasts during the Soviet era. Russian also achieved significant usage particularly in commerce.

Russian was the most commonly studied foreign language at all levels of schooling during the Soviet era. Despite schooling available and administration conducted in local languages, Russian settlers were neither encouraged nor motivated to learn the official local languages, so knowledge of Russian became a practical necessity in daily life. Even to this day, the majority of the population of the Baltic states profess to be proficient in Russian, especially those who lived during Soviet rule. Meanwhile, the minority of Russian origin generally do not speak the national language. The question of their assimilation is a major factor in social and diplomatic affairs.[50]

Sports

Basketball is a notable sport across the Baltic states. Teams from the three countries compete in the respective national championships and the Baltic Basketball League. The Lithuanian teams have been the strongest, with the BC Žalgiris winning the 1999 FIBA Euroleague.

The Lithuania men's national basketball team has won the EuroBasket on three occasions and has claimed third place at the 2010 World Cup and three Olympic tournaments. Meanwhile, the Latvia men's national basketball team won the 1935 Eurobasket and finished second in 1939, but has performed poorly since the 1990s. Lithuania hosted the Eurobasket in 1939 and 2011, whereas Latvia was one of the hosts in 2015. The historic Lithuanian basketball team Kauno Žalgiris won the Euroleague in 1999. However, the Latvia women's national basketball team finished fourth at the 2007 Eurobasket.

Ice hockey is also popular in Latvia. Dinamo Riga is the country's strongest hockey club, playing in the Kontinental Hockey League. The 2006 Men's World Ice Hockey Championships were held in Latvia.

Association football is popular in the Baltic states, but the only appearance of a Baltic team in a major international competition was Latvia's qualification for Euro 2004. The national teams of the three states have played in the Baltic Cup since 1928.

Estonian and Soviet chess grandmaster Paul Keres was among the world's top players from the mid-1930s to the mid-1960s. He narrowly missed a chance at a World Chess Championship match on five occasions.

Estonian Markko Märtin was successful in the World Rally Championship in the early 2000s, where he got five wins and 18 podiums, as well as a third place in the 2004 drivers' championship.

Ott Tänak of Estonia won the 2019 World Rally Championship.[51]

Latvian tennis player Jeļena Ostapenko won the 2017 French Open, another Latvian tennis player Ernests Gulbis was a semi-finalist at the 2010 Rome Masters and 2014 French Open.

Geography

Nature

Forests cover over half the landmass of Estonia

Forests cover over half the landmass of Estonia Devonian sandstone cliffs in Gauja National Park, Latvia's largest and oldest national park

Devonian sandstone cliffs in Gauja National Park, Latvia's largest and oldest national park- View from the Bilioniai forthill in Lithuania

.jpg) Sand dunes of the Curonian Spit near Nida, which are the highest drifting sand dunes in Europe (UNESCO World Heritage Site).[52]

Sand dunes of the Curonian Spit near Nida, which are the highest drifting sand dunes in Europe (UNESCO World Heritage Site).[52]

Statistics

General statistics

All three are Unitary republics, joined the European Union on 1 May 2004, share EET/EEST time zone schedules and euro currency.

| Estonia | Latvia | Lithuania | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coat of arms |  |

.svg.png) |

|

N/A |

| Flag | N/A | |||

| Capital | Tallinn | Riga | Vilnius | N/A |

| Independence |

|

N/A | ||

| Political system | Parliamentary republic | Parliamentary republic | Semi-presidential republic | N/A |

| Parliament | Riigikogu | Saeima | Seimas | N/A |

| Current President | Kersti Kaljulaid | Egils Levits | Gitanas Nausėda | N/A |

| Population (2020) | ||||

| Area | 45,339 km2 = 17,505 sq mi | 64,589 km2 = 24,938 sq mi | 65,300 km2 = 25,212 sq mi | 175,228 km2 = 67,656 sq mi |

| Density | 29/km2 = 75/sq mi | 31/km2 = 79/sq mi | 44/km2 = 115/sq mi | 35/km2 = 92/sq mi |

| Water area % | 4.56% | 1.5% | 1.35% | 2.23% |

| GDP (nominal) total (2019)[56] | €28.037 billion | €30.476 billion | €48.339 billion | €106.852 billion |

| GDP (nominal) per capita (2019)[56] | €21,200 | €15,900 | €17,300 | €17,700 |

| Military budget (2020) | €615 million[57] | €664 million[58] | €1.017 billion[59] | €2.296 billion |

| Gini Index (2015)[60] | 32.7 | 34.2 | 37.4 | N/A |

| HDI (2019)[61] | 0.882 (Very High) | 0.854 (Very High) | 0.869 (Very High) | N/A |

| Internet TLD | .ee | .lv | .lt | N/A |

| Calling code | +372 | +371 | +370 | N/A |

Cities

See also

- Baltia

- Baltic Entente

- Baltic Free Trade Area

- Baltic provinces

- Baltic region

- Baltic Tiger

- Baltic Way

- Baltoscandia

- Balts, Baltic Finns, Baltic Germans and Baltic Russians

- Eastern Europe

- June deportation

- List of cities in the Baltic states by population

- Nordic countries

- Nordic Estonia

- Nordic-Baltic Eight

- Northern Europe

- Occupation of the Baltic states

- Operation Priboi

- Scandinavia

- Soviet deportations from Estonia

- United Baltic Duchy

References

- "Baltic Cooperation | Ministry of Foreign Affairs". vm.ee. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Baltic Cooperation | Ministry of Foreign Affairs".

- "Colombia and Lithuania join the OECD". France 24. 30 May 2018.

- Lukoševičius, Viktoras; Duksa, Tomas. "ERATOSTHENES' MAP OF THE OECUMENE". GEODESY AND CARTOGRAPHY. Taylor & Francis. 38(2): 84. eISSN 2029-7009. ISSN 2029-6991.

- "Indo-European Etymology: Query result". starling.rinet.ru. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Dini, Pierto Umberto (2000) [1997]. Baltu valodas (in Latvian). Translated from Italian by Dace Meiere. Riga: Jānis Roze. ISBN 978-9984-623-96-2.

- Krauklis, Konstantīns (1992). Latviešu etimoloģijas vārdnīca (in Latvian). I. Rīga: Avots. pp. 103–104. OCLC 28891146.

- Bojtar, Endre (1999). Foreword to the Past: A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Central European University Press. ISBN 9789639116429.

- Skutāns, Gints. "Latvija – jēdziena ģenēze". old.historia.lv. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- l.l.b, charles mayo (1804). a compendious view of universal history. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (2006). The Life of Nelson. Bexley Publications. ISBN 978-1-4116-7198-0. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- Tarlow, Sarah (30 September 2015). The Archaeology of Death in Post-medieval Europe. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-043973-1.

- Kasekamp, Andres (30 August 2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-36450-9.

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (1998). A history of Eastern Europe: crisis and change. Routledge. p. 122. ISBN 978-0415161114.

- "The Grand Duchy of Lithuania, 13–18th century". Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "Ништадтский мир" [Treaty of Nystad]. Great Soviet Encyclopedia. 30: Николаев – Олонки (2nd ed.). Moscow: Сов. энциклопедия. 1954.

- Ragsdale, Hugh; V. N. Ponomarev (1993). Imperial Russian foreign policy. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-521-44229-9.

- Matthews, W. K. (May 1947). "Nationality and Language in the East Baltic Area". American Slavic and East European Review. 6 (1/2): 62–78. doi:10.2307/2491934. JSTOR 2491934.

- Maude, George (2010). Aspects of the Governing of the Finns. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0713-9.

- Smele, John (1996). Civil war in Siberia: the anti-Bolshevik government of Admiral Kolchak, 1918–1920. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 305.

- Calvo, Carlos (2009). Dictionnaire Manuel de Diplomatie et de Droit International Public et Privé. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. p. 246. ISBN 9781584779490.

- "Why did Finland remain a democracy between the two World Wars, whereas the Baltic States developed authoritarian regimes?". January 2004.

as [Lithuania] is a distinct case from the other two Baltic countries. Not only was an authoritarian regime set up in 1926, eight years before those of Estonia and Latvia, but it was also formed not to counter a threat from the right, but through a military coup d'etat against a leftist government. (...) The hostility between socialists and non-socialists in Finland had been amplified by a bloody civil war

- "These Names Accuse—Nominal List of Latvians Deported to Soviet Russia". latvians.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Kangilaski, Jaak; Salo, Vello; Komisjon, Okupatsioonide Repressiivpoliitika Uurimise Riiklik (2005). The white book: losses inflicted on the Estonian nation by occupation regimes, 1940–1991. Estonian Encyclopaedia Publishers. ISBN 9789985701959.

- "Communism and Crimes against Humanity in the Baltic states". 13 April 1999. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- "Murder of the Jews of the Baltic States". Yad Vashem.

- "Country Profiles: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania". Foreign & Commonwealth Office – Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 31 July 2003. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "U.S.-Baltic Relations: Celebrating 85 Years of Friendship". U.S. Department of State. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- Norman Kempster, Annexed Baltic States : Envoys Hold On to Lonely U.S. Postings Archived 19 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times, 31 October 1988. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- Beissinger, Mark R. (2009). "The intersection of Ethnic Nationalism and People Power Tactics in the Baltic States". In Adam Roberts; Timothy Garton Ash (eds.). Civil resistance and power politics: the experience of non-violent action from Gandhi to the present. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 231–246. ISBN 978-0-19-955201-6.

- Pike, John. "Baltic Military District". Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "SKRUNDA SHUTS DOWN. – Jamestown". Jamestown. 1 September 1993. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "The Latvians in Sydney". Sydney Journal. 1. March 2008. ISSN 1835-0151. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Mart, Kuldkepp. "Swedish political attitudes towards Baltic independence in the short twentieth century". Ajalooline Ajakiri. The Estonian Historical Journal (3/4). ISSN 2228-3897.

- N., Kristensen, Gustav (2010). Born into a Dream : Eurofaculty and the Council of the Baltic Sea States. Berlin: BWV Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8305-2548-6. OCLC 721194688.

- "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Latvia: Co-operation among the Baltic States". 4 December 2008. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Upleja, Sanita (10 November 1998). "Ilvess neapšauba Baltijas valstu politisko vienotību" (in Latvian). Diena. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- "Kersti Kaljulaid: Let's talk about the Nordic Benelux". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Zeng, Shouzhen; Streimikiene, Dalia; Baležentis, Tomas (September 2017). "Review of and comparative assessment of energy security in Baltic States". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 76: 185–192. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.037. ISSN 1364-0321.

- Kisel, Einari; Hamburg, Arvi; Härm, Mihkel; Leppiman, Ando; Ots, Märt (August 2016). "Concept for Energy Security Matrix". Energy Policy. 95: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2016.04.034.

- Molis, Arūnas (September 2011). "Building methodology, assessing the risks: the case of energy security in the Baltic States". Baltic Journal of Economics. 11 (2): 59–80. doi:10.1080/1406099x.2011.10840501. ISSN 1406-099X.

- Mauring, Liina (2006). "The Effects of the Russian Energy Sector on the Security of the Baltic States". Baltic Security & Defence Review. 8: 66–80. ISSN 2382-9230.

- da Graça Carvalho, Maria (April 2012). "EU energy and climate change strategy". Energy. 40 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2012.01.012.

- Nader, Philippe Bou (1 June 2017). "The Baltic states should adopt the self-defence pinpricks doctrine: the "accumulation of events" threshold as a deterrent to Russian hybrid warfare". Journal on Baltic Security. 3 (1): 11–24. doi:10.1515/jobs-2017-0003. ISSN 2382-9230.

- Vértesy, László (2018). "Macroeconomic Legal Trends in the EU11 Countries" (PDF). Public Governance, Administration and Finances Law Review. 3 (1).

- "Pilsonības un migrācijas lietu pārvalde – Kļūda 404" (PDF). pmlp.gov.lv.

- "POPULATION BY SEX, ETHNIC NATIONALITY AND COUNTY, 1 JANUARY. ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION AS AT 01.01.2018". pub.stat.ee. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Home – Oficialiosios statistikos portalas". osp.stat.gov.lt.

- "Baltic states – Soviet Republics". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- Nikolas K. Gvosdev; Christopher Marsh (2013). Russian Foreign Policy: Interests, Vectors, and Sectors. CQ Press. p. 217. ISBN 9781483322087.

- "Standings". Federation Internationale de l'Automobile. 22 January 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- "Nida and The Curonian Spit, The Insider's Guide to Visiting". MapTrotting. 23 September 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Immigration exceeded emigration for the third year in a row". Statistics Estonia. 9 May 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- "The number of population is decreasing – the mark has dropped below 2 million". Statistikas datubāzes. 30 June 2011. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- "Pradžia – Oficialiosios statistikos portalas". osp.stat.gov.lt.

- "Eurostat - Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table".

- "Defence budget – Kaitseministeerium". kaitseministeerium.ee.

- "Latvia's defence spending to reach 2% of GDP in 2018 – Jane's 360". janes.com.

- Bns. "2020 METŲ ASIGNAVIMAI KRAŠTO APSAUGAI".

- "GINI index (World Bank estimate) | Data". World Bank. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "| Human Development Reports". Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

Further reading

- Bojtár, Endre (1999). Forward to the Past – A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-42-9.

- Bousfield, Jonathan (2004). Baltic States. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-85828-840-6.

- Clerc, Louis; Glover, Nikolas; Jordan, Paul, eds. Histories of Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding in the Nordic and Baltic Countries: Representing the Periphery (Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2015). 348 pp. ISBN 978-90-04-30548-9. for an online book review see online review

- D'Amato, Giuseppe (2004). Travel to the Baltic Hansa – The European Union and its enlargement to the East (Book in Italian: Viaggio nell'Hansa baltica – L'Unione europea e l'allargamento ad Est). Milano: Greco&Greco editori. ISBN 978-88-7980-355-7.

- Hiden, John; Patrick Salmon (1991). The Baltic Nations and Europe: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in the Twentieth Century. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-08246-5.

- Hiden, John; Vahur Made; David J. Smith (2008). The Baltic Question during the Cold War. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-56934-7.

- Jacobsson, Bengt (2009). The European Union and the Baltic States: Changing forms of governance. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-48276-9.

- Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-01940-9.

- Lane, Thomas; Artis Pabriks; Aldis Purs; David J. Smith (2013). The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-48304-2.

- Lehti, Marko; David J. Smith, eds. (2003). Post-Cold War Identity Politics – Northern and Baltic Experiences. London/Portland: Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7146-8351-5.

- Lieven, Anatol (1993). The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Path to Independence. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05552-8.

- Naylor, Aliide (2020). The Shadow in the East: Vladimir Putin and the New Baltic Front. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1788312523.

- O'Connor, Kevin (2006). Culture and Customs of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33125-1.

- O'Connor, Kevin (2003). The History of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32355-3.

- Plakans, Andrejs (2011). A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54155-8.

- Smith, Graham (1994). The Baltic States: The National Self-determination of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-12060-3.

- Palmer, Alan. The Baltic: A new history of the region and its people (New York: Overlook Press, 2006; published in London with the title Northern shores: a history of the Baltic Sea and its peoples (John Murray, 2006).

- Šleivyte, Janina (2010). Russia's European Agenda and the Baltic States. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-55400-8.

- Vilkauskaite, Dovile O. "From Empire to Independence: The Curious Case of the Baltic States 1917-1922." (thesis, University of Connecticut, 2013). online; Bibliography pp 70 – 75.

- Williams, Nicola; Debra Herrmann; Cathryn Kemp (2003). Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (3rd ed.). London: Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74059-132-4.

International peer-reviewed media

- On the Boundary of Two Worlds: Identity, Freedom, and Moral Imagination in the Baltics (book series)

- Journal of Baltic Studies, journal of the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies (AABS)

- Lituanus, journal dedicated to Lithuanian and Baltic art, history, language, literature and related cultural topics

- The Baltic Course, International Internet Magazine. Analysis and background information on Baltic markets

- Baltic Reports, English-language daily news website that covers all three Baltic states

- The Baltic Review, the independent newspaper from the Baltics

- The Baltic Times, independent weekly newspaper that covers latest political, economic, business, and cultural events in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania

- The Baltics Today, news about The Baltics

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Baltic states. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baltic states. |

- The Baltic Sea Information Centre

- vifanord – a digital library that provides scientific information on the Nordic and Baltic countries

- Baltic states – The article about Baltic states on Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Richter, Klaus: Baltic States and Finland, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

.png)

.jpg)