History of Lithuanian culture

The culture of Lithuania, dating back to 200 BC, with the settlement of the Balts and has been independent of the presence of a sovereign Lithuanian state.[1]

Pre-Lithuanian period (before the 10th century AD)

The Lithuanian nation rose between the 7th and 9th centuries CE. Earlier, the Balts, ancestors of Lithuanians and Latvians, had arrived at the territories between the Dnepr and Daugava rivers and the Baltic Sea. An Indo-European people, the Balts are presumed to have come from a hypothetic original homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans; many scientists date this arrival to 3rd millennium BCE.

The Balts, who are believed to have arrived with the main wave of Indo-Europeans, were unconnected with the formation of later Indo-European nations in Southern and Western Europe. Thus, the Balts' culture is believed to have preserved primeval features of Indo-European culture for a longer time. When later contacts with newly formed European nations increased, differences between the Balts' primeval culture and the culture of the new European nations were so great that closer cultural interchange was difficult. This resulted in preservation of the Balts' Indo-European roots but may also have contributed to their isolation.

After the period of Gothic domination in Europe, the culture of the Balts appeared in a more restricted territory between the Wisla and Daugava rivers. Almost anything said about the Balts' cultural isolation level in these times is speculation, but it was likely decreasing. Still, the Balts conserved forms of ancient Indo-European proto-language until much later times. The most archaic language forms were preserved by the Western Balts, who lived approximately in the territory of later Prussia (today's Kaliningrad and north-west Poland). These dialects developed into Old Prussian language, which became extinct by the beginning of the 18th century.

The Eastern Balts had less archaic forms of language. For example, some popular simplifications took hold, such as a decrease in the number of verb forms, which presumably happened when the ancient cultural elite lost its influence over the people. It may have taken place, for example, in times of "barbarian" invasions (not later than the 8th century). Later, eastern dialects of Balts developed into the modern Lithuanian and Latvian languages.

Knowledge about the Balts' cultural life in these times is scanty. It is known that Balts at the end of this period had a social structure comparable with that of Celtic people in South-West Europe during the 2nd—1st centuries BC.

In the 10th century, religious life of the Balts was not unified, with various forms of cults present. An important feature of Balt culture was willful avoidance of using material attainments in their religious life. Some more complicated forms of architecture, equipment, and literacy were disapproved of, even when these things were allowed by and were well known from neighbouring nations. Religious life was concentrated on verbal tradition, with singing and perhaps with some elements of mystery theatre. Material forms of this life were closely connected with unsophisticated wooden shrines, nature objects ( such as trees and stones), and special ornamented vestments and their accessories.

Period of the Lithuanian nation rising (10th – 14th centuries)

The Lithuanian nation began to form in about 7th – 8th centuries CE. The growing difference between Western and Eastern Balts was a result of some cultural modernization of the Eastern Balts even before this period. Differences also grew between northern and southern parts of the Eastern Balts. Lithuanians derived from the southern parts of Eastern Balts till 9th century CE. At this time, the Eastern Balts did not form any political unit. They were divided into some autonomous clans, but culturally and religiously, they were part of the Balts. The common name for them, Lithuanians, was already known.

Historians have occasionally attributed the name "Lithuania" of this period only to one of the Eastern Balts' tribes. It is not known for certain in what political circumstances Lithuanians acquired their common name, and whether it took place before the beginning of the 11th century, when the name was first mentioned in written sources, or later.

Traditionally, historians consider religion-based union of the Balts. This theory is supported by historical sources that wrote about existence of centers of religious life (named Romuva, using the present-day variant of this word), concentrated around more significant shrines, holy and mystic areas. Servants of these religious centers have influences on other not central shrines. This influence was based more on authority than on formal structure of organization. Finally, there is some historical data about the main religious center of all Balts. The level of organization and extent of this religious cooperation are under discussion. For example, some historians argue that union was more local and included only southern Balts (Lithuanians and Prussians), but Northern Balts (ancestors of Latvians) did not participate in it. Information concerning religious unity is influenced by later Lithuanian and Latvian myths and is not strongly based on historical sources and archaeological research.

The new point of distinguishing the Balts' nations and their cultural development was the occupation of a significant part of the land by Catholic military orders in the 13th century. The main areas of Western Balts, known under the name of Prussia, were occupied by Teutonic order. Livonian order occupied northern territories, beginning from areas around the Gulf of Riga, creating so-called Livonia.

Therefore, later cultural development of these two and the third unoccupied part of Balts' areas was different. Old Prussians (Balts) never regained a nation, but the Latvian nation was formed in Livonia. The third unoccupied part was a basis for the Lithuanian nation to form.

Outer aggression forced Baltic nations to form more strict institutions of political life. A Lithuanian state, Lithuania, was founded in 13th century and it included regions of still unoccupied Eastern Balts and remaining Western Balts' areas (These Western Balts' ethnic groups are known under names of Yotvingians and Sudovians).

In the middle of the 14th century, Lithuania emerged as a large eastern European state, with former Kievan Rus' and some Ruthenian regions to the north of it (approximately present Belarus) included. This expansion shows a great political potential of the Lithuanian ruling classes, and this potential could not be reached without respective cultural basis. Christian Ruthenian rulers became some kind of vassals of non-Christian Lithuanian rulers, but culturally the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (G.D.L.) remained bipolar. It consisted of a non-Christian Lithuanian part in North-West (later known as Lithuania Propria) and Eastern Christian Orthodox Ruthenian regions (partial Duchies).

The price of cooperation and recognition of pagan dominance by Ruthenian Orthodoxes in G.D.L. was recognition of wide cultural rights for orthodoxes. These rights included, for example, customs, that Lithuanian dukes had to be christened before taking office in a partial duchy in orthodox parts. Wives of Lithuanian dukes, if they were Ruthenians, stayed orthodox, but Grand Dukes in this case had to ensure that it was possible for his wife to perform orthodox rites and take part in orthodox services. Children of orthodox duchesses officially became observers of their father's religion, the old-Lithuanian one in that case. In reality, the religion of the mother could have some (sometimes great) influence.

In this period, both nations of G.D.L. insistently stood on their cultural basis, and the main directions of Lithuanian culture remained unchanged until Christianization. Lithuanian culture stayed far from growing significant literacy in Europe and there were no significant changes, for example, in cult architecture. However, there were some new tendencies too. Religious intolerance, hardly avoidable during religiously-based war as with crusaders, was offset by tolerance to orthodox Christians, so the Lithuanian community stayed tolerant in the cultural and religious sense. There were some attempts to modernize Lithuanian religious life too. For example, there were at least two Christian churches, Catholic and orthodox, both of brick stonework, in Vilnius town. The main shrine of the old-religion in the town was bricked, and not wooden as it was customary.

The Early Christian period (the end of the 14th to the middle of the 15th century)

Cultural changes in higher estates

The cultural background of formation and persistence of higher estates before Christianization is almost unknown. Christianization of Lithuania brought changes towards European feudalism of the 15th century. It is logical that Lithuanian political culture had some influence of Western European and, especially, Ruthenian feudalism before Christianization, but the christening broke the isolation barrier and the influence became more direct.

Adding to this, the strengthening of Western cultural constituent by Christianization mostly affected political culture. For example, this situation caused interesting effects on jurisprudence. Presence of old Ruthenian legal norms and old Lithuanian traditions as well as coming of Western European legal norms raised various inconveniences, and, in the beginning of the 16th century, the Lithuanian law codex, the First Statute of Lithuania of 1529 was issued. Lithuanian law was exercised in the territory of G.D.L. till 1840, survived not only times of state independence before Union of Lublin of 1569, but the state itself. Thus, since its beginning, Lithuanian law became one of the factors of political integrity of G.D.L. and distinguished Lithuania from other European regions including The Crown of the Polish Kingdom.

The issuance of the codex is an illustration of two different tendencies in the political elite of G.D.L. The issuance of a written law codex shows a significant western influence on Lithuanian political culture of this time. However, the existence of a Lithuanian system of law shows that cultural differences from Western Europe existed and were acknowledged by ruling classes.

In this time, Lithuanians were getting acquainted with Western European culture and this process had interesting discoveries, which also caused later ruling political ideas. However, the process was not trivial. To become "educated in aristocratic manner" a Lithuanian had to learn at least three languages: Ruthenian, Polish and Latin. German with variety of its dialects and Italian were also used. In reality, this educational objective could not usually be realised, so knowledge of languages (and even cultural orientation) depended on estate of person. Priests and humanitarians learned Latin, merchants learnt German. Polish was preferred by the upper classes, but Ruthenian by the lower strata of nobles.

Since the end of the 14th century, Lithuanians began to study in universities abroad, mostly in Kraków and Prague Universities and, sometimes, in Western European ones. Latin, being a church and humanitarian language, was studied by a number of Lithuanian citizens, mostly Catholics. Latin had a specific reason to be considered interesting for Lithuanian-speaking Lithuanians. Being acquainted with Latin language, Lithuanian humanitarians discovered great similarities between a large number of Lithuanian and Latin words, such as (Lithuanian words are given in their modern form) aušra – aurora (a dawn), dūmas – fumus (fume, smoke), mėnesis – mensis (a month), senis – senex (an old man) and so on. This paradoxical similarity was explained by raising an idea that the Lithuanian language was directly derived from Latin.

This idea, joined with one, maybe earlier, myth about modernized cultural hero Palemon, treating him as a Latin language pioneer in earlier pre-Christian Lithuania, has a great influence to the political mindset of noble Lithuanians. It constricted an area of Lithuanian cultural independence, prescribing to Lithuanians affinity with Italics and showing Lithuanian culture as secondary, derivative and mixed. On the other hand, it stimulated patriotism, arguing that Lithuanian popular culture is more "Latin" than Polish and German cultures, so more cultured according to the thinking of that time. This theory raised the prestige of old Lithuania (thought of by neighbors as "pagan" and "barbarian") firstly in the eyes of Lithuanians themselves, and had the same effect on foreign people (especially Poles, who often treated their mediating in Lithuania's Christianization as their own cultural achievement against "eastern" or "pagan" "barbarism").

Despite using the existence of the Lithuanian language as a patriotic argument, the usage of the language itself became more and more narrow among the higher strata of nobles. The Ruthenian language became official after the Christianization, for it had more developed written tradition and, maybe, because of negative attitude of Orthodox nobles towards the Lithuanian language. During the 15th century, Ruthenian language anchored more in all machinery of the state. As it was common European tendency of the 15th to 17th centuries to make the transition from feudalism to bigger state dominance, the role of the state grew, and prestige of Lithuanian language decreased. Documents of Lithuanian law were written in Ruthenian, and it looked normal. Usage of Ruthenian however never reached amounts of official language usage in modern sense, and stayed comparable with usage of Latin in Medieval Europe.

On the other hand, not only Ruthenian, but Latin and Polish also narrowed Lithuanian language usage. The Great Duke of Lithuania (later, also the king of Poland) Alexander (as the Great Duke reigned 1492–1506) was taught "Lithuanian language". Even if "Lithuanian" does not mean "Ruthenian", Alexander would have been the last Great Duke who knew Lithuanian.

The loss of ethnic basis did not reduce patriotism among nobles. The variegate Lithuanian mythology of this time (legend about emigration of Palemon from Rome to Lithuania, legend about the founding of the capital of Lithuania Vilnius by Duke Gediminas, and other pieces) had been presented in a spirit of high lucid and virtuous patriotism.

Original architectural style (with Western-European and Byzantine tendencies fused in it) and other manifestations of material culture of this time prove Lithuania as a distinctive cultural unit. However, Lithuania was too little known to Western Europeans in these times.

The Middle Christian period (The mid 16th – 17th century)

The Protestant Reformation in Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Protestant Reformation was met differently by different strata of Lithuanians. Ruling classes entered into the Reformation struggles both on pro and contra sides. Urban people in the biggest towns, especially in the Catholic part of Grand Duchy of Lithuania (G.D.L.), were involved in these struggles too, mostly as clients of some persons of influence in the highest stratum. Ordinary people of towns played a role of believers in both Catholic and Protestant churches. From the mid 16th century until the end of the Reformation, sporadic street scuffles between Catholic and Protestant hotheads were often found in these towns. However even in the time of the religious struggle, some partial tolerance existed, and both involved sides proclaimed their abstinence from solving the question in the form of violence. The scuffles always were restricted by officials and they never grew into military conflicts or massacre.

The answer of ordinary country people to the Reformation was their return to "paganism". After some stabilization, both Catholic Jesuits in G.D.L. and Protestant priests in Prussia describe the situation such, as if Lithuania was christened not before 250 years, but still before the events. It seems likely that both sources described this situation so emphatically in order to simulate bigger merits in rechristening. But it also points out that "pagan" tendencies still existed not only in a subconscious form, but also in performing rites. Besides to it, Christian life had to remain in some forms in country-regions too.

It must also be emphasized that the eastern part of G.D.L. stayed orthodox and orthodox culture had its broad cultural life. The same can be said about Jewish, Tatar and Karait minorities in G.D.L. And all these facts show how variegated and different-sided the cultural situation in Lithuania was.

Adding to this, there were some tendencies in cultural life of G.D.L. not directly connected with religious problems on Reformation background. In the first place, absorption of ideas of Western cultural development in 13th – 16th centuries by nobles (especially, urban ones). Italian cultural ideas of Rinascemento had an especially big influence. They were reflected on literature (written mostly in Latin or Polish, or, in case of orthodox, in Ruthenian).

The main reasons for such exceptional thoughts of Italy were conservatism of Lithuanians and position of the Royal court. All facts showed Italy to Lithuanians as a country of ancient and high culture. Additionally, the Queen of Poland wife of Sigismund I Bona was Italian. Thus despite the growth of Reformation, the cultural orientation hadn't changed.

The Reformation in Lithuania remained on the level of political and religious regulating ideas and didn't turn into a cultural movement as it did in West European countries. disputes about the Reformation were in the form of peaceful verbal discussion among the highest estate of the country. And in these discussions, the Latin language, eloquence, citation and knowledge of ancient philosophers referred more to Italy than to any other country of Western Europe.

In this atmosphere Catholics decided to use this cultural attachment to improve their position. Their leaders decided to found a unit of Jesuit order in Lithuania (Jesuits were known as masters of discussion and providers of a modernized Latin-based scholastic education). In their turn Jesuits founded the University of Vilnius (officially 1579). Students and graduates of the University soon became true supporters of the Catholic Church.

These events caused the wave of Reformation to fall. With the decrees of Reformation aspirations in the higher strata, activity of reformers among the rest of the urban population was more and more restricted by officials. Thus after the middle of the 17th century, the non-Orthodox part of Lithuania became firmly Catholic (with a Protestant minorities in some towns like Vilnius, Kėdainiai, and Biržai).

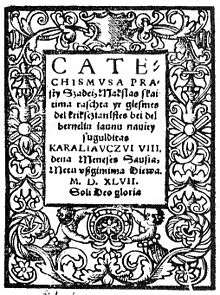

Printing of books

Another cultural factor, not connected with the reformation directly, was printing of books. The first printed books reached Lithuania before the beginning of the Reformation. But multiplied religious discussions and the increase of printing in Western Europe both activated interest in printing books in Lithuania. The first book in the Lithuanian language was printed in 1547 in Königsberg (it was a Protestant Catechism by Martynas Mažvydas). The first typography in G.D.L. was opened in approx. 1575 in Vilnius.

Presence of printed books became the signal factor to change ancient Lithuanian cultural attitude against literacy. The necessity of literacy became evident. But in G.D.L. at the same time the growing of literacy coincided with refusal of Lithuanian culture among the nobility.

Lithuanian-language culture

Background

Lithuanian-language culture derived directly from old Lithuanian culture, among lower strata prevalently. The language barrier caused it to remain isolated from innovations in culture in the 15th century. However the Christianity of higher estates and presence of Christian parishes even in country regions weakened a base of old religion and induced some non direct changes towards culture, based on common European values.

The higher strata in Lithuania for unknown reasons accepted innovations in culture directly, without any attempts at inculturation or adaptation to local cultural thinking. It meant accepting of extraneous culture in all its complexity, with using new language and so on. So, old Lithuanian culture (or, as a later form, Lithuanian-language culture) was negated and rejected by a part of the population in Lithuanian part of G.D.L., especially by the highest estates since approx. middle 15th century. This situation became a serious impediment to Lithuanian-language culture. Lithuanians of lower estates could not become acquainted with European Christian culture, but their peculiar cultural life was strongly slowed too. So all later facts of Lithuanian cultural life till the middle of the 19th century were more or less sporadic.

National Lithuanian culture did not become a factor of unification of Lithuanian elite during this period. Christianity was declared then as such a factor, but different European cultural influences made this idea complex. There were followers of Polish, German, Italian cultures, and Protestants and Catholics contested in Lithuania in that time. And both orthodoxes and Jews, even if they stayed a bit in a side, contributed to all this variety. - But this situation saved Lithuanian-language culture as well. Being strictly negated, it also did not have clear directions of change and stayed original. In its turn this having no direction was dangerous for self-isolation and remaining stagnate without creative flight.

When the Catholic Church (or the Lutheran one, if we speak about Lithuanians in Prussia) became a provider of new ideas for Lithuanian people, it became something like a window to the extraneous world. It's a question how much this role was accepted voluntary by the church. Some historians argue that it was made by pressure of rivalry between Catholics and Protestants and it weakened when Reformation struggles decreased.

At any rate, the other, opposite to negating Lithuanian culture, tendency had its supporters too. Even more, these two tendencies, the inculturating and the negating one, remained as two main components in Lithuanian culture till the beginning of the 19th century and have their evident consequences now.

The development

Changes of old Lithuanian culture became mostly evident in a sphere of religion. We know only approximately what new elements had been introduced into (old) Lithuanian culture, clothing and so on in the beginning of this period. But the popular-kind simplifying (or becoming more rustic) of old Lithuanian religion is an unquestioned thing. The ritual became strictly connected with the calendar of rural works and other factors of this kind; witnesses of that time found a multitude of sacred objects (they simply described them as "gods"), which were connected totally with all material life, but didn't refer to more philosophically common or abstract ideas (in opposition to descriptions of religion in the 14th century). It allows us to think about some form of pantheism, as if all the world was holy for Lithuanians.

This old vision of the world retreated slowly and finally was extinguished in the end of the 18th century. There were two stages of this process. Firstly the extinguishing of original attributes of the old religion, as names, forms of rite, details of clothing, and especially words of holy prayers, songs and poems. All these traditional forms still had some existence in the 16th century, but they became less and less known a century later. And we can date the beginning of the new stage approximately to the last quarter of the 16th century.

Two other processes started in this time. The first was stabilization of some old cultural forms, maybe less confronting to Christian requirements. Later, some of them survived the time of the very understanding old culture values and became known by neighboring nations as Lithuanian popular traditions since the middle of the 19th century or sporadically even earlier. The traditional popular songs (dainos) and Lithuanian woven sashes (juostos) are among them. Lithuanians began to create the songs in these times instead of forgotten or forbidden old holy songs and prayers. The melodic base of dainos, especially in the very beginning, was the same as in these songs. Juostos had been woven by women since old times. During this period they became the main ware, in which traditional Lithuanian ornaments still were used. The ornaments may have had some conventional symbolic significance, but during this period they began to be seen only as forms of art, which later developed into a standard of Lithuanian popular art.

The second process, which took place after the end of the 16th century, was introduction of ideas of Christianity into the Lithuanian environment, using Lithuanian culture's symbols and traditions. This program was initiated by Jesuits (in G.D.L. only). The worship of various old religion holy essences was changed into cult of saints. On the other hand, traditional Catholic art forms of sacred objects were supplemented in Lithuania by some forms, which were comparable with ones, taken from old Lithuanian art ware. As the best example, traditional (both iron and wooden) crosses in present Lithuania, West Belarus and Northern Poland with raying sun and moon could be noted. In this case we can see old symbols still having symbolic (maybe different from pre-Christian times) sense too. During this period, new forms were added to country art. Local craftsmen made (mostly wooden) statues of saints, chapels, wooden an iron crosses (statues and chapels often had well-seen prototypes, made by famous European artists, but there were also original ones). Till the 19th century it became a significant branch of Lithuanian country art, known and used also by urban people.

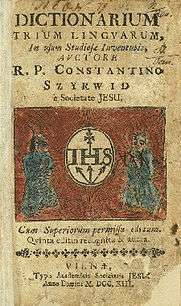

This program of inculturation required a good knowledge of the Lithuanian language. The superiors of Jesuits in Lithuania always paid some (though not very big) attention to it. The time after founding Jesuits in Lithuania was exceptional in this point. The rivalry with Reformers and, maybe, more direct survey from Rome caused, that attention, paid to Lithuanian language by Jesuits was greater, than before or after it. Jesuit Lithuanian Daukša even wrote a manifesto (printed in his Postil, a collection of sermons in Lithuanian, in 1599), in which he exhorted Lithuanian nobles to regard and to use the Lithuanian language. Twenty years later the first dictionary with Lithuanian words was published (Polish–Latin–Lithuanian dictionary by Jesuit priest Konstantinas Sirvydas, in approx. 1620) and it became a significant fact of Lithuanian cultural life. The dictionary had a big influence to the development of Lithuanian language, especially to its standardization and modernization. Adding to this, the Lithuanian language was presented in a satisfactory form in the dictionary, with borrowings forming only a small part of the entire word corpus. And it meant not only a difference of Lithuanian-language culture from others, but also a big potential of this culture.

So the short period during which Lithuanian-language culture was fostered by the Society of Jesus had positive effects.

After the middle of the 17th century, a moderate rise of Lithuanian-speaking culture took place. Politically it was the time of turmoils and wars. Despite of it towns were growing in Lithuania and various new realities came into life. The number of urban people increased and newcomers (in much cases Lithuanian-speaking) had significant input to it. The degree of communication between state and town officials and ordinary inhabitants increased as well. This development caused necessary changes in language policy. In non-orthodox regions of G.D.L. the middle and lower strata of urban people used the Lithuanian language. And only some regions in the South of G.D.L. as Grodna, Augustów regions and Vilnius town (not region) were exceptions to it, having however Lithuanian-speaking population parts, mostly in lower strata. This situation caused it to be necessary for the highest stratum of nobles to know the Lithuanian language too. The prestige of Lithuanian language was increasing at this time and we can speak about some relative expansion and renovation of Lithuanian-speaking culture.

Lithuanian didn't gain official status then. Among various causes of it, some more significant must be emphasized. Firstly, the two biggest towns in G.D.L. were polonized earlier and more than other towns. Secondly, position of Catholic church in G.D.L. was favorable to Polish language. Adding to this, whereas publishing of books was sponsored by the highest nobles and by Catholic and Orthodox churches, publishing of books in Lithuanian did not increase. Lithuanian-language books became more and more inconspicuous among Polish and Latin publications.

As a result, the Lithuanian-speaking culture did not expand among the highest nobles. But some positive changes took place in this time too. The language was modernized, it was no longer a language of mere country people. Style of courtesy re-appeared in the language (some style of this kind had to exist in pre-Christian Lithuania). All this contributed to the existence of a Lithuanian-speaking culture among further generations of nobles and urban people. And these processes, going on only on a part of the territory of G.D.L., were a sign of a growing modern Lithuania.

Lithuanian-language culture in the Duchy of Prussia

Lithuanians, mostly villagers, lived in the North and North-East regions of the Duchy of Prussia. This fact was confirmed later in administrative way, and administrative unit, called Lithuanian counties was created. Unofficially it was called Lithuania, Prussian Lithuania, or, in later times, also Lithuania Minor. In the beginning of the 16th century, Lithuanians in Prussia had the same cultural traditions as neighboring Lithuanians in G.D.L., and some inessential differences are not worth mentioning here.

But later the cultural difference between Prussian Lithuania and Lithuanian part of G.D.L. increased. The main points of this process were: In 1530, Prussia became a secular Protestant state. So Prussian Lithuanians became Protestants (Lutherans), while Lithuanians in G.D.L. stayed Catholics. The next point was presence of some official attention to religious education in the native language in Prussia. At the beginning, after 1530, for this purpose the first secular ruler of Prussia, the duke Albert invited a number of educated Lithuanians Protestants from G.D.L. They became senior priests in Prussian Lithuania and authors of church texts, holy songs in Lithuanian and their translations into Lithuanian, but one of them, Martynas Mažvydas, wrote a catechism, which was published in 1547 in Königsberg, becoming the first printed book in Lithuanian.

Since this time priests of Lithuanian parishes were obliged to know the Lithuanian language and they did this obligation more or less. There were talented persons among them, and sometimes books in Lithuanian with new translations of religious texts, new holy songs and so on were published. In 1653 the first Lithuanian grammar, Grammatica Litvanica by Daniel Klein, was issued in Königsberg. And unpublished material on Lithuanian language and culture, collected by them, was big too.

The interest of Lutheran priests of Prussian Lithuanian parishes in Lithuanian language was deeper than the interest of their Catholic colleagues in G.D.L., and they managed to print more books for a relatively small Lithuanian population in Prussia, than Catholic editors for all Lithuanian population in G.D.L.

Catholic priests paid less attention towards Lithuanian popular traditions than Lutheran ones. Also the existence of G.D.L. had some influence to Prussian ruling persons and even put some pressure on them, and it did not allow disregarding of existing Lithuanians and their cultural needs. And the situation of Lithuanians was better, than, for example, the Old Prussian population, whose language was called "barbarian" and attained only minimal attention.

Despite good attention to the Lithuanian language, Lithuanians were not admitted to the Prussian ruling class, which remained German. And the church career was the only one available for Lithuanians. Concentration of Lithuanian intellectuals in priest estate had some significant consequences. The Lithuanian language remained in usage in Prussian Lithuania till the beginning of the 20th century and later. Besides this, Lithuanians became loyal and faithful to Evangelical Church in Prussia and Protestantism, their faith assumed some forms of pietism. And, in its turn, they became loyal and devoted subjects and patriots of Prussia. Thus, in fact, this part of the Lithuanian nation was separated from the main part in G.D.L. during this period.

The later part of Middle Christian period from the end of the 17th century to the mid-19th century suffered a period of decline for the Grand duchy of Lithuania.

List of cultural events of the 18th to the 20th centuries

The table below contains the main historical events connected with cultural life in Lithuania in the 18th to 20th centuries.

| Date or period | Events in the G.D.L. | Events in East Prussia (Prussian Lithuania, or Lithuania Minor) |

|---|---|---|

| The first half of the 18th century | After a plague epidemic in the beginning of the century, Prussian authorities start colonization of empty villages in Prussian Lithuania by colonists from other territories of Prussia. At the same time, they hinder settling from neighboring territories of G.D.L., where Lithuanians live. It contributes to later Germanization of Prussian Lithuania. | |

| The middle of the 18th century | Lutheran priest of Tolminkiemis (German variant Tolmingkehm) Kristijonas Donelaitis writes the first work of fiction in Lithuanian language, the poem about life of peasants in Lithuania, Metai (The Year). It was published after the author's death in the beginning of the 19th century. | |

| Second half of the 18th century | In the wake of cultural polonization of the highest aristocratic estate and linguistical polonization of main towns, cultural polonization of the nation begins. The Lithuanian and Belarusian-speaking majority accepts this process without resistance. | |

| Second half of the 18th century | The last relics of the old religion disappear in Lithuania. Personages of rich spoken tradition are not treated as gods or god-like figures anymore. | |

| 1794 | The Kościuszko Uprising raises Polish patriotic feelings among urban population in the G.D.L. | |

| The 19th century |

|

The same processes of growing education and literacy precede ones in the former G.D.L. by 20 – 30 years. |

| The first half of the 19th century | Polish national Renaissance begins. Poles of Lithuania much contribute to it. The main known names are: poets Adam Mickiewicz, Ludwik Kondratowicz known as Syrokomla and others. |

|

| 1800 | Philosopher Immanuel Kant writes the article, defending cultural rights of Lithuanians. | |

| 1818–1825 | Prussian humanitarian (of Lithuanian origin) Ludwig Rhesa publishes poem Metai (The Year) by Kristijonas Donelaitis(see this table above) (in 1818) and its translation to German language and selected examples of Lithuanian folk songs, also with their German translations (in 1925). | |

| The middle of the 19th century | Interest in Lithuanian history, its cultural origins increases among Polish-speaking intellectuals in Lithuania. Archeological and ethnographic research is conducted in Lithuania. | |

| 1835–1841 | Lithuanian Pole Theodor Narbutt writes a wide, romantically colored History of Lithuania. Being written in Polish language and promoting Polish humanitarian values, it however shows the Lithuanian nation and history as heroic and unique, and this historical work becomes one of flags for all the movement, mentioned above. | |

| 1845 | Manners of ancient Lithuanians Aukštaitians and Samogitians (Būdas senovės Lietuvių kalnėnų žemaičių) by Simonas Daukantas is published.

It is a history of the culture of Lithuania and the first printed historical work in Lithuanian. |

|

| The second half of the 19th century |

|

|

| 1864–1904 | Russian authorities forbid public use of the Lithuanian language and use of Latin-based alphabet for it. Lithuanian people begin wide resistance, not accepting Lithuanian books, printed in Cyrillic script. | |

| Lithuanians print books abroad (mostly in nearby Prussia) and haul them secretly to Lithuania. | Prussian Lithuanians do a great job, printing and transporting Lithuanian books. | |

| 1883 | Lithuanian monthly Aušra (the Dawn) starts to be issued in Tilžė (German variant, Tilsit), East Prussia. In this political and cultural monthly the difference between the Lithuanian nation and Poles and necessity to stand on unity of both parts of Lithuanian nation (Catholic, being under Russian rule and Lutheran under German one) are declared clearly for the first time. The new modern definition of Lithuanian nation, given in Aušra, will become basic one in modern Lithuania later. | |

| 1905–1918 | Lithuanian leaders widely expand Lithuanian cultural life, using modern means. Many Lithuanian societies, choirs, and amateur theaters begin their existence. Lithuanian books and newspapers are published widely in Lithuania. Somewhat limited lithuanization of primary schools begins. | |

| 1918 |

|

|

| 1919 | The first Lithuanian professional theater opens its doors in Kaunas. | |

| 1920 | The first democratic elections in Lithuania. | |

| 1922 | The University of Lithuania is founded in Kaunas. | |

See also

- History of Lithuania

- Lithuania

- Central Lithuania

- Baltic region

- Baltic Germans

- Architecture of Lithuania

- Lithuanian name

References

- History & Culture of Lithuania History Archived 2007-02-11 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on May 31, 2007