European Space Agency

The European Space Agency ![]()

![]()

| |

| |

ESA Headquarters in Paris, France | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Abbreviation |

|

| Formed | 30 May 1975 |

| Type | Space agency |

| Headquarters | Paris, Île-de-France, France |

| Official language | English, French and German[1][2] |

| Administrator | Johann-Dietrich Wörner Director General |

| Primary spaceport | Guiana Space Centre |

| Owner | |

| Annual budget | (~US$7.43 billion) (2020)[3] |

| Website | www |

ESA's space flight programme includes human spaceflight (mainly through participation in the International Space Station program); the launch and operation of uncrewed exploration missions to other planets and the Moon; Earth observation, science and telecommunication; designing launch vehicles; and maintaining a major spaceport, the Guiana Space Centre at Kourou, French Guiana. The main European launch vehicle Ariane 5 is operated through Arianespace with ESA sharing in the costs of launching and further developing this launch vehicle. The agency is also working with NASA to manufacture the Orion Spacecraft service module, that will fly on the Space Launch System.[8][9]

The agency's facilities are distributed among the following centres:

- ESA science missions are based at ESTEC in Noordwijk, Netherlands;

- Earth Observation missions at ESA Centre for Earth Observation in Frascati, Italy;

- ESA Mission Control (ESOC) is in Darmstadt, Germany;

- the European Astronaut Centre (EAC) that trains astronauts for future missions is situated in Cologne, Germany;

- the European Centre for Space Applications and Telecommunications (ECSAT), a research institute created in 2009, is located in Harwell, England;

- and the European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC) is located in Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain.

The European Space Agency Science Programme is a long-term programme of space science and space exploration missions.

History

Foundation

After World War II, many European scientists left Western Europe in order to work with the United States. Although the 1950s boom made it possible for Western European countries to invest in research and specifically in space-related activities, Western European scientists realised solely national projects would not be able to compete with the two main superpowers. In 1958, only months after the Sputnik shock, Edoardo Amaldi (Italy) and Pierre Auger (France), two prominent members of the Western European scientific community, met to discuss the foundation of a common Western European space agency. The meeting was attended by scientific representatives from eight countries, including Harrie Massey (United Kingdom).

The Western European nations decided to have two agencies: one concerned with developing a launch system, ELDO (European Launch Development Organization), and the other the precursor of the European Space Agency, ESRO (European Space Research Organisation). The latter was established on 20 March 1964 by an agreement signed on 14 June 1962. From 1968 to 1972, ESRO launched seven research satellites.

ESA in its current form was founded with the ESA Convention in 1975, when ESRO was merged with ELDO. ESA had ten founding member states: Belgium, Denmark, France, West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.[10] These signed the ESA Convention in 1975 and deposited the instruments of ratification by 1980, when the convention came into force. During this interval the agency functioned in a de facto fashion. ESA launched its first major scientific mission in 1975, Cos-B, a space probe monitoring gamma-ray emissions in the universe, which was first worked on by ESRO.

Later activities

ESA collaborated with NASA on the International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE), the world's first high-orbit telescope, which was launched in 1978 and operated successfully for 18 years. A number of successful Earth-orbit projects followed, and in 1986 ESA began Giotto, its first deep-space mission, to study the comets Halley and Grigg–Skjellerup. Hipparcos, a star-mapping mission, was launched in 1989 and in the 1990s SOHO, Ulysses and the Hubble Space Telescope were all jointly carried out with NASA. Later scientific missions in cooperation with NASA include the Cassini–Huygens space probe, to which ESA contributed by building the Titan landing module Huygens.

As the successor of ELDO, ESA has also constructed rockets for scientific and commercial payloads. Ariane 1, launched in 1979, carried mostly commercial payloads into orbit from 1984 onward. The next two versions of the Ariane rocket were intermediate stages in the development of a more advanced launch system, the Ariane 4, which operated between 1988 and 2003 and established ESA as the world leader[11] in commercial space launches in the 1990s. Although the succeeding Ariane 5 experienced a failure on its first flight, it has since firmly established itself within the heavily competitive commercial space launch market with 82 successful launches until 2018. The successor launch vehicle of Ariane 5, the Ariane 6, is under development and is envisioned to enter service in the 2020s.

The beginning of the new millennium saw ESA become, along with agencies like NASA, JAXA, ISRO, the CSA and Roscosmos, one of the major participants in scientific space research. Although ESA had relied on co-operation with NASA in previous decades, especially the 1990s, changed circumstances (such as tough legal restrictions on information sharing by the United States military) led to decisions to rely more on itself and on co-operation with Russia. A 2011 press issue thus stated:[12]

Russia is ESA's first partner in its efforts to ensure long-term access to space. There is a framework agreement between ESA and the government of the Russian Federation on cooperation and partnership in the exploration and use of outer space for peaceful purposes, and cooperation is already underway in two different areas of launcher activity that will bring benefits to both partners.

Notable ESA programmes include SMART-1, a probe testing cutting-edge space propulsion technology, the Mars Express and Venus Express missions, as well as the development of the Ariane 5 rocket and its role in the ISS partnership. ESA maintains its scientific and research projects mainly for astronomy-space missions such as Corot, launched on 27 December 2006, a milestone in the search for exoplanets.

On 21 January 2019, ArianeGroup and Arianespace announced a one-year contract with ESA to study and prepare for a mission to mine the Moon for lunar regolith.[13]

Mission

The treaty establishing the European Space Agency reads:[14]

ESA's purpose shall be to provide for, and to promote, for exclusively peaceful purposes, cooperation among the European States in space research and technology and their space applications, with a view to their being used for scientific purposes and for operational space applications systems

ESA is responsible for setting a unified space and related industrial policy, recommending space objectives to the member states, and integrating national programs like satellite development, into the European program as much as possible.[14]

Jean-Jacques Dordain – ESA's Director General (2003–2015) – outlined the European Space Agency's mission in a 2003 interview:[15]

Today space activities have pursued the benefit of citizens, and citizens are asking for a better quality of life on Earth. They want greater security and economic wealth, but they also want to pursue their dreams, to increase their knowledge, and they want younger people to be attracted to the pursuit of science and technology. I think that space can do all of this: it can produce a higher quality of life, better security, more economic wealth, and also fulfill our citizens' dreams and thirst for knowledge, and attract the young generation. This is the reason space exploration is an integral part of overall space activities. It has always been so, and it will be even more important in the future.

Activities and programmes

ESA describes its work in two overlapping ways:

- For the general public, the various fields of work are described as Activities.

- Budgets are organized as Programmes (British spelling retained because it is a term of official documents). These are either Mandatory or Optional.

Activities

According to the ESA website, the activities are:

- Observing the Earth

- Human Spaceflight

- Launchers

- Navigation

- Space Science

- Space Engineering & Technology

- Operations

- Telecommunications & Integrated Applications

- Preparing for the Future

- Space for Climate

Programmes

Mandatory

Every member country must contribute to these programmes:[19]

- Technology Development Element Programme[20]

- Science Core Technology Programme

- General Study Programme

- European Component Initiative

Optional

Depending on their individual choices the countries can contribute to the following programmes, listed according to:[21]

- Launchers

- Earth Observation

- Human Spaceflight and Exploration

- Telecommunications

- Navigation

- Space Situational Awareness

- Technology

ESA_LAB@

ESA has formed partnerships with universities. ESA_LAB@ refers to research laboratories at universities. Currently there are ESA_LAB@

- Technische Universität Darmstadt[22]

- École des hautes études commerciales de Paris (HEC Paris)[23]

- Université de recherche Paris Sciences et Lettres[24]

- University of Central Lancashire[25]

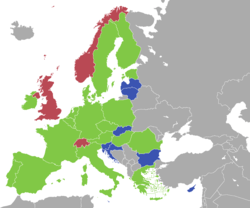

Member states, funding and budget

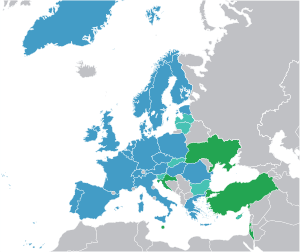

Membership and contribution to ESA

By 2015, ESA was an intergovernmental organisation of 22 member states.[6] Member states participate to varying degrees in the mandatory (25% of total expenditures in 2008) and optional space programmes (75% of total expenditures in 2008).[26] The 2008 budget amounted to €3.0 billion the 2009 budget to €3.6 billion.[27] The total budget amounted to about €3.7 billion in 2010, €3.99 billion in 2011, €4.02 billion in 2012, €4.28 billion in 2013, €4.10 billion in 2014 and €4.33 billion in 2015.[28][29][30][31][32] English is the main language within ESA. Additionally, official documents are also provided in German and documents regarding the Spacelab are also provided in Italian. If found appropriate, the agency may conduct its correspondence in any language of a member state.

The following table lists all the member states and adjunct members, their ESA convention ratification dates, and their contributions in 2020:[3]

| Member state/Source | ESA convention | National programme | Contr. (mill. €) |

Contr. (%) |

Contr. per capita (€)[33] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria[note 1] | 30 December 1986 | FFG | 51.2 | 1.0% | 5.37 |

| Belgium[note 2] | 3 October 1978 | BELSPO | 210.0 | 4.3% | 17.82 |

| Czech Republic[note 3] | 12 November 2008 | Ministry of Transport | 44.7 | 0.9% | 3.06 |

| Denmark[note 2] | 15 September 1977 | DTU Space | 33.8 | 0.7% | 5.47 |

| Estonia[note 3] | 4 February 2015 | ESO | 3.7 | 0.1% | 1.97 |

| Finland[note 3] | 1 January 1995 | Business Finland | 27.4 | 0.6% | 3.52 |

| France[note 2] | 30 October 1980 | CNES | 1,311.7 | 26.9% | 14.30 |

| Germany[note 2] | 26 July 1977 | DLR | 981.7 | 20.1% | 11.11 |

| Greece[note 3] | 9 March 2005 | HSA | 20.6 | 0.4% | 0.98 |

| Hungary[note 3] | 24 February 2015 | HSO | 11.7 | 0.2% | 0.63 |

| Ireland[note 1] | 10 December 1980 | EI | 24.8 | 0.5% | 3.60 |

| Italy[note 2] | 20 February 1978 | ASI | 665.8 | 13.7% | 7.77 |

| Luxembourg[note 3] | 30 June 2005 | Luxinnovation | 29.9 | 0.6% | 44.19 |

| Netherlands[note 2] | 6 February 1979 | NSO | 100.3 | 2.1% | 5.32 |

| Norway[note 1] | 30 December 1986 | NSA | 86.3 | 1.8% | 12.09 |

| Poland[note 3] | 19 November 2012 | POLSA | 38.4 | 0.8% | 0.91 |

| Portugal[note 3] | 14 November 2000 | FCT | 21.0 | 0.4% | 1.77 |

| Romania[note 3] | 22 December 2011 | ROSA | 34.3 | 0.7% | 2.18 |

| Spain[note 2] | 7 February 1979 | INTA | 249.5 | 5.1% | 4.39 |

| Sweden[note 2] | 6 April 1976 | SNSA | 83.2 | 1.7% | 7.15 |

| Switzerland[note 2] | 19 November 1976 | SSO | 167.0 | 3.4% | 17.61 |

| United Kingdom[note 2] | 28 March 1978 | UKSA | 464.3 | 9.5% | 5.05 |

| Other | — | — | 181.3 | 3.7% | |

| Non-full members | |||||

| Canada[note 4] | 1 January 1979[42] | CSA | 28.0 | 0.6% | 0.53 |

| Slovenia | 5 July 2016[44] | 3.2 | 0.1% | 1.31 | |

| Total members and associates | 4,870.0 | 100% | |||

| European Union[note 5] | 28 May 2004[45] | ESP | 1,683.3 | 93.0% | 2.56 |

| EUMETSAT | — | — | 54.3 | 3.0% | |

| Other income | — | — | 72.4 | 4.0% | |

| Total other institutional partners | 1,810.0 | 100% | |||

| Total ESA | 6,680.0 |

- These nations are considered initial signatories, but since they were members of neither ESRO nor ELDO (the precursor organisations to ESA) the Convention could only enter into force when the last of the other 10 founders ratified it.

- Founding members and initial signatories drafted the ESA charter which entered into force on 30 October 1980. These nations were also members of either ELDO or ESRO.[34]

- Acceded members became ESA member states upon signing an accession agreement.[35][36][37][38][39][40][41]

- Canada is a Cooperating State of ESA.[42][43]

- Framework Agreement establishing the legal basis for cooperation between ESA and the European Union came into force in May 2004.

Non-full member states

Slovenia

Currently the only associated member state is Slovenia.[44] Previously associated members were Austria, Norway and Finland, all of which later joined ESA as full members.

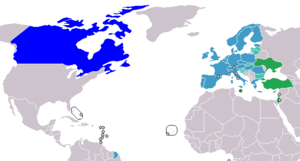

Canada

Since 1 January 1979, Canada has had the special status of a Cooperating State within ESA. By virtue of this accord, the Canadian Space Agency takes part in ESA's deliberative bodies and decision-making and also in ESA's programmes and activities. Canadian firms can bid for and receive contracts to work on programmes. The accord has a provision ensuring a fair industrial return to Canada.[46] The most recent Cooperation Agreement was signed on 2010-12-15 with a term extending to 2020.[47][48] For 2014, Canada's annual assessed contribution to the ESA general budget was €6,059,449 (CAD$8,559,050).[49] For 2017, Canada has increased its annual contribution to €21,600,000 (CAD$30,000,000).[50]

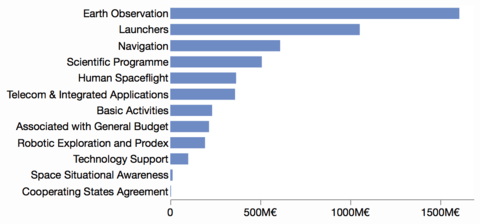

Budget appropriation and allocation

ESA is funded from annual contributions by national governments as well as from an annual contribution by the European Union (EU).[51]

The budget of ESA was €5.250 billion in 2016.[52] Every 3–4 years, ESA member states agree on a budget plan for several years at an ESA member states conference. This plan can be amended in future years, however provides the major guideline for ESA for several years. The 2016 budget allocations for major areas of ESA activity are shown in the chart on the right.[52]

Countries typically have their own space programmes that differ in how they operate organisationally and financially with ESA. For example, the French space agency CNES has a total budget of €2015 million, of which €755 million is paid as direct financial contribution to ESA.[53] Several space-related projects are joint projects between national space agencies and ESA (e.g. COROT). Also, ESA is not the only European governmental space organisation (for example European Union Satellite Centre).

Enlargement

After the decision of the ESA Council of 21/22 March 2001, the procedure for accession of the European states was detailed as described the document titled "The Plan for European Co-operating States (PECS)".[54] Nations that want to become a full member of ESA do so in 3 stages. First a Cooperation Agreement is signed between the country and ESA. In this stage, the country has very limited financial responsibilities. If a country wants to co-operate more fully with ESA, it signs a European Cooperating State (ECS) Agreement. The ECS Agreement makes companies based in the country eligible for participation in ESA procurements. The country can also participate in all ESA programmes, except for the Basic Technology Research Programme. While the financial contribution of the country concerned increases, it is still much lower than that of a full member state. The agreement is normally followed by a Plan For European Cooperating State (or PECS Charter). This is a 5-year programme of basic research and development activities aimed at improving the nation's space industry capacity. At the end of the 5-year period, the country can either begin negotiations to become a full member state or an associated state or sign a new PECS Charter.[55] Many countries, most of which joined the EU in both 2004 and 2007, have started to co-operate with ESA on various levels:

| Applicant state | EU membership | Cooperation Agreement | ECS Agreement | PECS Charter(s) | National Programme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey | No | 15 July 2004[56] | TUSA | ||

| Ukraine | No | 25 January 2008[57] | SSAU | ||

| Slovenia | 2004 | 28 May 2008[58] | 22 January 2010[59] | 30 November 2010[60] | through MoHEST |

| Latvia | 2004 | 23 July 2009[61] | 19 March 2013[62] | 30 January 2015[63] | through MoES |

| Cyprus | 2004 | 27 August 2009[64] | 6 July 2016[65] | through MoCW | |

| Slovakia | 2004 | 28 April 2010[66] | 16 February 2015[67] | through MoE | |

| Lithuania | 2004 | 7 October 2010[68] | 10 October 2014[69] | LSA[70][71] | |

| Israel | No | 30 January 2011[72] | ISA | ||

| Malta | 2004 | 20 February 2012[73] | MCST[74] | ||

| Bulgaria | 2007 | 8 April 2015[75] | 4 February 2016[76] | SRTI | |

| Croatia | 2013 | 19 February 2018[77] | through MoSE |

During the Ministerial Meeting in December 2014, ESA ministers approved a resolution calling for discussions to begin with Israel, Australia and South Africa on future association agreements. The ministers noted that "concrete cooperation is at an advanced stage" with these nations and that "prospects for mutual benefits are existing".[78]

A separate space exploration strategy resolution calls for further co-operation with the United States, Russia and China on "LEO exploration, including a continuation of ISS cooperation and the development of a robust plan for the coordinated use of space transportation vehicles and systems for exploration purposes, participation in robotic missions for the exploration of the Moon, the robotic exploration of Mars, leading to a broad Mars Sample Return mission in which Europe should be involved as a full partner, and human missions beyond LEO in the longer term."[78]

EU and the European Space Agency

The political perspective of the European Union (EU) was to make ESA an agency of the EU by 2014,[79] although this date was not met. The EU is already the largest single donor to ESA's budget and non-ESA EU states are observers at ESA.

Launch vehicle fleet

ESA has a fleet of different launch vehicles in service with which it competes in all sectors of the launch market. ESA's fleet consists of three major rocket designs: Ariane 5, Soyuz-2 and Vega. Rocket launches are carried out by Arianespace, which has 23 shareholders representing the industry that manufactures the Ariane 5 as well as CNES, at ESA's Guiana Space Centre. Because many communication satellites have equatorial orbits, launches from French Guiana are able to take larger payloads into space than from spaceports at higher latitudes. In addition, equatorial launches give spacecraft an extra 'push' of nearly 500 m/s due to the higher rotational velocity of the Earth at the equator compared to near the Earth's poles where rotational velocity approaches zero.

Ariane 5

The Ariane 5 rocket is ESA's primary launcher. It has been in service since 1997 and replaced Ariane 4. Two different variants are currently in use. The heaviest and most used version, the Ariane 5 ECA, delivers two communications satellites of up to 10 tonnes into GTO. It failed during its first test flight in 2002, but has since made 82 consecutive successful flights until a partial failure in January 2018. The other version, Ariane 5 ES, was used to launch the Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) to the International Space Station (ISS) and will be used to launch four Galileo navigational satellites at a time.[80][81]

In November 2012, ESA agreed to build an upgraded variant called Ariane 5 ME (Mid-life Evolution) which would increase payload capacity to 11.5 tonnes to GTO and feature a restartable second stage to allow more complex missions. Ariane 5 ME was scheduled to fly in 2018,[82] but the whole project was scrapped in favor of Ariane 6, planned to replace Ariane 5 in the 2020s.

ESA's Ariane 1, 2, 3 and 4 launchers (the last of which was ESA's long-time workhorse) have been retired.

Soyuz

Soyuz-2 (also called the Soyuz-ST or Soyuz-STK) is a Russian medium payload launcher (ca. 3 metric tons to GTO) which was brought into ESA service in October 2011.[83][84] ESA entered into a €340 million joint venture with the Russian Federal Space Agency over the use of the Soyuz launcher.[12] Under the agreement, the Russian agency manufactures Soyuz rocket parts for ESA, which are then shipped to French Guiana for assembly.

ESA benefits because it gains a medium payload launcher, complementing its fleet while saving on development costs. In addition, the Soyuz rocket—which has been the Russian's space launch workhorse for more than 50 years—is proven technology with a very good safety record. Russia benefits in that it gets access to the Kourou launch site. Due to its proximity to the equator, launching from Kourou rather than Baikonur nearly doubles Soyuz's payload to GTO (3.0 tonnes vs. 1.7 tonnes).

Soyuz first launched from Kourou on 21 October 2011, and successfully placed two Galileo satellites into orbit 23,222 kilometres above Earth.[83]

Vega

Vega is ESA's carrier for small satellites. Developed by seven ESA members led by Italy, it is capable of carrying a payload with a mass of between 300 and 1500 kg to an altitude of 700 km, for low polar orbit. Its maiden launch from Kourou was on 13 February 2012.[85] Vega began full commercial exploitation in December 2015[86]

The rocket has three solid propulsion stages and a liquid propulsion upper stage (the AVUM) for accurate orbital insertion and the ability to place multiple payloads into different orbits.[87][88]

Ariane launch vehicle development funding

Historically, the Ariane family rockets have been funded primarily "with money contributed by ESA governments seeking to participate in the program rather than through competitive industry bids. This [has meant that] governments commit multiyear funding to the development with the expectation of a roughly 90% return on investment in the form of industrial workshare." ESA is proposing changes to this scheme by moving to competitive bids for the development of the Ariane 6.[89]

Human space flight

History

At the time ESA was formed, its main goals did not encompass human space flight; rather it considered itself to be primarily a scientific research organisation for uncrewed space exploration in contrast to its American and Soviet counterparts. It is therefore not surprising that the first non-Soviet European in space was not an ESA astronaut on a European space craft; it was Czechoslovak Vladimír Remek who in 1978 became the first non-Soviet or American in space (the first man in space being Yuri Gagarin of the Soviet Union) – on a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft, followed by the Pole Mirosław Hermaszewski and East German Sigmund Jähn in the same year. This Soviet co-operation programme, known as Intercosmos, primarily involved the participation of Eastern bloc countries. In 1982, however, Jean-Loup Chrétien became the first non-Communist Bloc astronaut on a flight to the Soviet Salyut 7 space station.

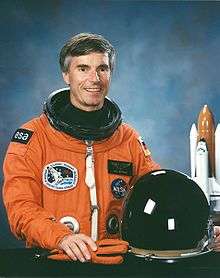

Because Chrétien did not officially fly into space as an ESA astronaut, but rather as a member of the French CNES astronaut corps, the German Ulf Merbold is considered the first ESA astronaut to fly into space. He participated in the STS-9 Space Shuttle mission that included the first use of the European-built Spacelab in 1983. STS-9 marked the beginning of an extensive ESA/NASA joint partnership that included dozens of space flights of ESA astronauts in the following years. Some of these missions with Spacelab were fully funded and organizationally and scientifically controlled by ESA (such as two missions by Germany and one by Japan) with European astronauts as full crew members rather than guests on board. Beside paying for Spacelab flights and seats on the shuttles, ESA continued its human space flight co-operation with the Soviet Union and later Russia, including numerous visits to Mir.

During the latter half of the 1980s, European human space flights changed from being the exception to routine and therefore, in 1990, the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne, Germany was established. It selects and trains prospective astronauts and is responsible for the co-ordination with international partners, especially with regard to the International Space Station. As of 2006, the ESA astronaut corps officially included twelve members, including nationals from most large European countries except the United Kingdom.

In the summer of 2008, ESA started to recruit new astronauts so that final selection would be due in spring 2009. Almost 10,000 people registered as astronaut candidates before registration ended in June 2008. 8,413 fulfilled the initial application criteria. Of the applicants, 918 were chosen to take part in the first stage of psychological testing, which narrowed down the field to 192. After two-stage psychological tests and medical evaluation in early 2009, as well as formal interviews, six new members of the European Astronaut Corps were selected – five men and one woman.[90]

Astronaut names

The astronauts of the European Space Agency are:

- France Jean-François Clervoy[note 1]

- Italy Samantha Cristoforetti[note 2][note 3]

- Belgium Frank De Winne[note 3]

- Spain Pedro Duque[note 3]

- Germany Reinhold Ewald[note 1]

- France Léopold Eyharts[note 1][note 3]

- Germany Alexander Gerst[note 2][note 3]

- Italy Umberto Guidoni[note 4][note 3]

- Sweden Christer Fuglesang[note 3]

- Netherlands André Kuipers[note 3]

- Germany Matthias Maurer[note 2]

- Denmark Andreas Mogensen[note 2]

- Italy Paolo Nespoli[note 3]

- Switzerland Claude Nicollier[note 4]

- Italy Luca Parmitano[note 2][note 3]

- United Kingdom Timothy Peake[note 2][note 3]

- France Philippe Perrin[note 4][note 3]

- France Thomas Pesquet[note 2]

- Germany Thomas Reiter[note 1][note 3]

- Germany Hans Schlegel[note 3]

- Germany Gerhard Thiele[note 4]

- France Michel Tognini[note 4][note 1]

- Italy Roberto Vittori[note 3]

- have visited Mir

- 2009 selection

- have visited the International Space Station

- now retired

Crew vehicles

In the 1980s, France pressed for an independent European crew launch vehicle. Around 1978 it was decided to pursue a reusable spacecraft model and starting in November 1987 a project to create a mini-shuttle by the name of Hermes was introduced. The craft was comparable to early proposals for the Space Shuttle and consisted of a small reusable spaceship that would carry 3 to 5 astronauts and 3 to 4 metric tons of payload for scientific experiments. With a total maximum weight of 21 metric tons it would have been launched on the Ariane 5 rocket, which was being developed at that time. It was planned solely for use in low Earth orbit space flights. The planning and pre-development phase concluded in 1991; the production phase was never fully implemented because at that time the political landscape had changed significantly. With the fall of the Soviet Union ESA looked forward to co-operation with Russia to build a next-generation space vehicle. Thus the Hermes programme was cancelled in 1995 after about 3 billion dollars had been spent. The Columbus space station programme had a similar fate.

In the 21st century, ESA started new programmes in order to create its own crew vehicles, most notable among its various projects and proposals is Hopper, whose prototype by EADS, called Phoenix, has already been tested. While projects such as Hopper are neither concrete nor to be realised within the next decade, other possibilities for human spaceflight in co-operation with the Russian Space Agency have emerged. Following talks with the Russian Space Agency in 2004 and June 2005,[91] a co-operation between ESA and the Russian Space Agency was announced to jointly work on the Russian-designed Kliper, a reusable spacecraft that would be available for space travel beyond LEO (e.g. the moon or even Mars). It was speculated that Europe would finance part of it. A €50 million participation study for Kliper, which was expected to be approved in December 2005, was finally not approved by the ESA member states. The Russian state tender for the project was subsequently cancelled in 2006.

In June 2006, ESA member states granted 15 million to the Crew Space Transportation System (CSTS) study, a two-year study to design a spacecraft capable of going beyond Low-Earth orbit based on the current Soyuz design. This project was pursued with Roskosmos instead of the cancelled Kliper proposal. A decision on the actual implementation and construction of the CSTS spacecraft was contemplated for 2008. In mid-2009 EADS Astrium was awarded a €21 million study into designing a crew vehicle based on the European ATV which is believed to now be the basis of the Advanced Crew Transportation System design.[92]

In November 2012, ESA decided to join NASA's Orion programme. The ATV would form the basis of a propulsion unit for NASA's new crewed spacecraft. ESA may also seek to work with NASA on Orion's launch system as well in order to secure a seat on the spacecraft for its own astronauts.[93]

In September 2014, ESA signed an agreement with Sierra Nevada Corporation for co-operation in Dream Chaser project. Further studies on the Dream Chaser for European Utilization or DC4EU project were funded, including the feasibility of launching a Europeanized Dream Chaser onboard Ariane 5.[94][95]

Cooperation with other countries and organisations

ESA has signed co-operation agreements with the following states that currently neither plan to integrate as tightly with ESA institutions as Canada, nor envision future membership of ESA: Argentina,[96] Brazil,[97] China,[98] India[99] (for the Chandrayan mission), Russia[100] and Turkey.[101]

Additionally, ESA has joint projects with the European Union, NASA of the United States and is participating in the International Space Station together with the United States (NASA), Russia and Japan (JAXA).

European Union

ESA is not an agency or body of the European Union (EU), and has non-EU countries (Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom) as members. There are however ties between the two, with various agreements in place and being worked on, to define the legal status of ESA with regard to the EU.[102]

There are common goals between ESA and the EU. ESA has an EU liaison office in Brussels. On certain projects, the EU and ESA co-operate, such as the upcoming Galileo satellite navigation system. Space policy has since December 2009 been an area for voting in the European Council. Under the European Space Policy of 2007, the EU, ESA and its Member States committed themselves to increasing co-ordination of their activities and programmes and to organising their respective roles relating to space.[103]

The Lisbon Treaty of 2009 reinforces the case for space in Europe and strengthens the role of ESA as an R&D space agency. Article 189 of the Treaty gives the EU a mandate to elaborate a European space policy and take related measures, and provides that the EU should establish appropriate relations with ESA.

Former Italian astronaut Umberto Guidoni, during his tenure as a Member of the European Parliament from 2004 to 2009, stressed the importance of the European Union as a driving force for space exploration, "since other players are coming up such as India and China it is becoming ever more important that Europeans can have an independent access to space. We have to invest more into space research and technology in order to have an industry capable of competing with other international players."[104]

The first EU-ESA International Conference on Human Space Exploration took place in Prague on 22 and 23 October 2009.[105] A road map which would lead to a common vision and strategic planning in the area of space exploration was discussed. Ministers from all 29 EU and ESA members as well as members of parliament were in attendance.[106]

National space organisations of member states

- The Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES) (National Centre for Space Study) is the French government space agency (administratively, a "public establishment of industrial and commercial character"). Its headquarters are in central Paris. CNES is the main participant on the Ariane project. Indeed, CNES designed and tested all Ariane family rockets (mainly from its centre in Évry near Paris)

- The UK Space Agency is a partnership of the UK government departments which are active in space. Through the UK Space Agency, the partners provide delegates to represent the UK on the various ESA governing bodies. Each partner funds its own programme.

- The Italian Space Agency (Agenzia Spaziale Italiana or ASI) was founded in 1988 to promote, co-ordinate and conduct space activities in Italy. Operating under the Ministry of the Universities and of Scientific and Technological Research, the agency cooperates with numerous entities active in space technology and with the president of the Council of Ministers. Internationally, the ASI provides Italy's delegation to the Council of the European Space Agency and to its subordinate bodies.

- The German Aerospace Center (DLR) (German: Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt e. V.) is the national research centre for aviation and space flight of the Federal Republic of Germany and of other member states in the Helmholtz Association. Its extensive research and development projects are included in national and international cooperative programmes. In addition to its research projects, the centre is the assigned space agency of Germany bestowing headquarters of German space flight activities and its associates.

- The Instituto Nacional de Técnica Aeroespacial (INTA) (National Institute for Aerospace Technique) is a Public Research Organization specialised in aerospace research and technology development in Spain. Among other functions, it serves as a platform for space research and acts as a significant testing facility for the aeronautic and space sector in the country.

NASA

ESA has a long history of collaboration with NASA. Since ESA's astronaut corps was formed, the Space Shuttle has been the primary launch vehicle used by ESA's astronauts to get into space through partnership programmes with NASA. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Spacelab programme was an ESA-NASA joint research programme that had ESA develop and manufacture orbital labs for the Space Shuttle for several flights on which ESA participate with astronauts in experiments.

In robotic science mission and exploration missions, NASA has been ESA's main partner. Cassini–Huygens was a joint NASA-ESA mission, along with the Infrared Space Observatory, INTEGRAL, SOHO, and others. Also, the Hubble Space Telescope is a joint project of NASA and ESA. Future ESA-NASA joint projects include the James Webb Space Telescope and the proposed Laser Interferometer Space Antenna. NASA has committed to provide support to ESA's proposed MarcoPolo-R mission to return an asteroid sample to Earth for further analysis. NASA and ESA will also likely join together for a Mars Sample Return Mission.[107]

Cooperation with other space agencies

Since China has started to invest more money into space activities, the Chinese Space Agency has sought international partnerships. ESA is, beside the Russian Space Agency, one of its most important partners. Two space agencies cooperated in the development of the Double Star Mission.[108] In 2017, ESA sent two astronauts to China for two weeks sea survival training with Chinese astronauts in Yantai, Shandong.[109]

ESA entered into a major joint venture with Russia in the form of the CSTS, the preparation of French Guiana spaceport for launches of Soyuz-2 rockets and other projects. With India, ESA agreed to send instruments into space aboard the ISRO's Chandrayaan-1 in 2008.[110] ESA is also co-operating with Japan, the most notable current project in collaboration with JAXA is the BepiColombo mission to Mercury.

Speaking to reporters at an air show near Moscow in August 2011, ESA head Jean-Jacques Dordain said ESA and Russia's Roskosmos space agency would "carry out the first flight to Mars together."[111]

International Space Station

With regard to the International Space Station (ISS) ESA is not represented by all of its member states:[112] 10 of the 21 ESA member states currently participate in the project: Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. Austria, Finland and Ireland chose not to participate, because of lack of interest or concerns about the expense of the project. The United Kingdom withdrew from the preliminary agreement because of concerns about the expense of the project. Portugal, Luxembourg, Greece, the Czech Republic, Romania and Poland joined ESA after the agreement had been signed. ESA is taking part in the construction and operation of the ISS with contributions such as Columbus, a science laboratory module that was brought into orbit by NASA's STS-122 Space Shuttle mission and the Cupola observatory module that was completed in July 2005 by Alenia Spazio for ESA. The current estimates for the ISS are approaching €100 billion in total (development, construction and 10 years of maintaining the station) of which ESA has committed to paying €8 billion.[113] About 90% of the costs of ESA's ISS share will be contributed by Germany (41%), France (28%) and Italy (20%). German ESA astronaut Thomas Reiter was the first long-term ISS crew member.

ESA has developed the Automated Transfer Vehicle for ISS resupply. Each ATV has a cargo capacity of 7,667 kilograms (16,903 lb).[114] The first ATV, Jules Verne, was launched on 9 March 2008 and on 3 April 2008 successfully docked with the ISS. This manoeuvre, considered a major technical feat, involved using automated systems to allow the ATV to track the ISS, moving at 27,000 km/h, and attach itself with an accuracy of 2 cm.

As of 2013, the spacecraft establishing supply links to the ISS are the Russian Progress and Soyuz, European ATV, Japanese Kounotori (HTV), and the USA COTS program vehicles Dragon and Cygnus.

European Life and Physical Sciences research on board the International Space Station (ISS) is mainly based on the European Programme for Life and Physical Sciences in Space programme that was initiated in 2001.

Languages

According to Annex 1, Resolution No. 8 of the ESA Convention and Council Rules of Procedure,[4] English, French and German may be used in all meetings of the Agency, with interpretation provided into these three languages. All official documents are available in English and French with all documents concerning the ESA Council being available in German as well.

Facilities

- ESA Headquarters (HQ), Paris, France

- European Space Operations Centre (ESOC), Darmstadt, Germany

- European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC), Noordwijk, The Netherlands

- European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC), Madrid, Spain[115]

- European Centre for Space Applications and Telecommunications (ECSAT), Oxfordshire, United Kingdom[116]

- European Astronaut Centre (EAC), Cologne, Germany

- ESA Centre for Earth Observation (ESRIN), Frascati, Italy

- Guiana Space Centre (CSG), Kourou, French Guiana

- European Space Tracking Network (ESTRACK)

- European Data Relay System

ESA and the EU institutions

The Flag of Europe is the one to be flown in space during missions (for example it was flown by ESA's Andre Kuipers during Delta mission)

The Commission is increasingly working together towards common objectives. Some 20 per cent of the funds managed by ESA now originate from the supranational budget of the European Union. In recent years the ties between ESA and the European institutions have been reinforced by the increasing role that space plays in supporting Europe's social, political and economic policies.

The legal basis for the EU/ESA co-operation is provided by a Framework Agreement which entered into force in May 2004. According to this agreement, the European Commission and ESA co-ordinate their actions through the Joint Secretariat, a small team of EC's administrators and ESA executive. The Member States of the two organisations meet at ministerial level in the Space Council, which is a concomitant meeting of the EU and ESA Councils, prepared by Member States representatives in the High-level Space Policy Group (HSPG).

ESA maintains a liaison office in Brussels to facilitate relations with the European institutions.

Guaranteeing European access to space

In May 2007, the 29 European countries expressed their support for the European Space Policy in a resolution of the Space Council, unifying the approach of ESA with those of the European Union and their member states.

Prepared jointly by the European Commission and ESA's Director General, the European Space Policy sets out a basic vision and strategy for the space sector and addresses issues such as security and defence, access to space and exploration.

Through this resolution, the EU, ESA and their Member States all commit to increasing co-ordination of their activities and programmes and their respective roles relating to space.[117]

Incidents

On 3 August 1984 ESA's Paris headquarters were severely damaged and six people were hurt when a bomb exploded, planted by the far-left armed Action Directe group.[118]

On 14 December 2015, hackers from Anonymous breached ESA's subdomains and leaked thousands of login credentials.[119]

See also

- List of government space agencies

- List of directors general of the European Space Agency

- List of projects of the European Space Agency

- SEDS

- European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO)

- European Space Research Organisation (ESRO)

- European integration#Space

- Eurospace

European Union matters

References

- "Languages". Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- esa. "Frequently asked questions". Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "ESA - Funding". esa.int. 15 February 2020.

- "Annex 1 Resolution 8". ESA Convention and Council Rules of Procedure (PDF) (5th ed.). European Space Agency. March 2010. p. 116. ISBN 978-92-9092-965-9.

- "Agence spatiale européenne (ASE)" [European Space Agency (ESA)]. 23 February 2017. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- "Welcome to ESA: New Member States". ESA. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- esa. "What is ESA?". European Space Agency. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Orion". European Space Agency.

- "European Service Module". European Space Agency.

- "ESA turns 30! A successful track record for Europe in space" (Press release). European Space Agency. 31 May 2005.

- "Ariane 4 / Launchers / Our Activities / ESA". European Space Agency. 14 May 2004. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "Launchers Home: International cooperation". ESA. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Wehner, Mike (23 January 2019). "Mining on the moon could be a reality as early as 2025". New York Post. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- Article II, Purpose, Convention of establishment of a European Space Agency, SP-1271(E) from 2003 ."ESA's Purpose". European Space Agency. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Launching a New Era with JAXA: Interview with Jean-Jacques Dordain". JAXA. 31 October 2003. Archived from the original on 6 July 2005.

- http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Observing_the_Earth/Copernicus

- http://exploration.esa.int/mars/46048-programme-overview/

- http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Navigation/Galileo/What_is_Galileo

- "Mandatory activities – ITS, Space Activities and R&D Department". www.czechspaceportal.cz.

- esa. "About the Technology Development Element programme (TDE)". European Space Agency. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "FACT SHEET". European Space Agency.

- esa. "Gemeinsame Mission". European Space Agency (in German). Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "The creation of ESA_Lab@HEC, the first ESA_Lab@ between ESA and HEC Paris". European Space Agency. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- esa. "ESA and Université PSL agree plans for new ESA_Lab@ programme". European Space Agency. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- esa. "Setting Up an ESA_LAB". European Space Agency. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "ESA programmes with Czech participation" (PDF). Czech Space Office. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013.

- "ESA budget for 2009" (PDF). ESA. January 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "ESA Budget for 2013". esa.int. 24 January 2013.

- "ESA budget for 2011" (PPT). ESA. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "ESA budget for 2013". ESA. Archived from the original (JPG) on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "ESA Budget for 2014". esa.int. 29 January 2015.

- "ESA Budget for 2015". esa.int. 16 January 2015.

- For European states, population is taken from the 2018 column of https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tps00001&plugin=1. For Canada, see https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/180322/dq180322c-eng.htm.

- ESA Convention. Esa. STR. (7th ed.). European Space Agency Communications, ESTEC. December 2010. ISBN 978-92-9221-410-4. ISSN 0379-4067. Archived from the original on 6 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Poncelet, Jean-Pol; Fonseca-Colomb, Anabela; Grilli, Giulio (November 2004). "Enlarging ESA? After the Accession of Luxembourg and Greece" (PDF). ESA Bulletin (120): 48–53.

- "New Member States". esa.int. ESA. Archived from the original on 27 August 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Polish flag raised at ESA". esa.int. ESA. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Luxembourg becomes ESA's 17th Member State". esa.int. ESA. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Greece becomes 16th ESA Member State". esa.int. ESA. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Portugal becomes ESA's 15th Member State". esa.int. ESA. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "N° 9-1994: Finland becomes ESA's 14th Member State". esa.int. ESA. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Leclerc, G.; Lessard, S. (November 1998). "Canada and ESA: 20 Years of Cooperation" (PDF). ESA Bulletin (96). ISBN 92-9092-533-7.

- Dotto, Lydia (May 2002). Canada and The European Space Agency: Three Decades of Cooperation (PDF). European Space Agency.

- esa. "Slovenia signs Association Agreement".

- "Framework Agreement between the European Community and the European Space Agency". Consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- "ESA and Canada renew cooperation agreement, building on long-term partnership" (Press release). European Space Agency. 21 June 2000. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Minister Clement Welcomes Extension of Historic Partnership with European Space Agency" (Press release). Industry Canada. 15 December 2010.

- "Europe and Canada: Partners in Space A Model of International Co-Operation" (Press release). Canadian Space Agency. 15 December 2010. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016.

- "Disclosure of grants and contributions awards Fiscal Year 2013–2014 4th quarter". Canadian Space Agency. 2 January 2014.

- media, Government of Canada, Canadian Space Agency, Directions of communications, Information services and new. "2016–17 Report on Plans and Priorities". Canadian Space Agency website.

-

de Selding, Peter B. (29 July 2015). "Tough Sledding for Proposed ESA Reorganization". Space News. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

The four biggest ESA contributors, Germany and France followed by Italy and Britain – together account for 67 percent of the agency's funding – and more if the annual contribution from the European Union is taken into account.

- "ESA 2016 Budget by domain". European Space Agency. 14 January 2016.

- "Le CNES en bref". Centre National D'etudes Spatiales. CNES. Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- Zufferey, Bernard (22 November 2006). "The Plan for European Co-operating States (PECS): Towards an enlarged ESA Partnership" (PDF). European Space Agency. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- "PECS: General Overview". European Space Agency. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009.

- "ESA signs Cooperation Agreement with Turkey". European Space Agency. 6 September 2004. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "A cooperation agreement between the Government of Ukraine and the European Space Agency was signed in Paris". State Space Agency of Ukraine. Retrieved 25 January 2008.

- "Slovenian Government and ESA Sign Cooperation Agreement". Slovenian Government Communication Office. 28 May 2008. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008.

- "Slovenia becomes sixth ESA European Cooperating State". ESA. 25 January 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "European Space Agency selects and confirms ten Slovenian proposals". Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology of Slovenia. 3 December 2010. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- "Līgums ar Kosmosa aģentūru liks tiekties pēc augstākiem rezultātiem". Diena.lv (in Latvian). 23 July 2009. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- "Latvia becomes seventh ESA European Cooperating State". esa.int. ESA. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- "Signature of the PECS Charter between ESA and Latvia". ESA. 31 January 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- "Cyprus signs space agreement". Famagusta Gazette Online. 28 August 2009. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- "Cyprus becomes 11th ESA European Cooperating State".

- "Slovak Republic signs Cooperation Agreement". ESA. 4 May 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- esa. "Slovakia becomes ninth ESA European Cooperating State". European Space Agency. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Danuta Pavilenene (7 October 2010). "Lithuania signs agreement with European Space Agency". The Baltic Course.

- ESA (10 October 2014). "Lithuania becomes eighth ESA European Cooperating State".

- "Lithuanian Space Association". Lietuvos Kosmoso Asociacija. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- "Lithuania Signs Cooperation Agreement". European Space Agency. 12 October 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- "Israel signs Cooperation Agreement". ESA.int. 31 January 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Malta signs Cooperation Agreement". ESA. 23 February 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Malta exploring ways of collaborating with European Space Agency". EARSC. 20 June 2009. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2009.

- esa. "Bulgaria becomes tenth ESA European Cooperating State". European Space Agency. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- MoE. "Bulgaria signs PECS Charter". Ministry of Economics of Bulgaria. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- esa. "Croatia signs Cooperation Agreement". European Space Agency. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- "ESA Looks Toward Expansion, Deeper International Cooperation". Parabolicarc.com. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "Agenda 2011" (PDF). ESA.int. September 2007. BR-268. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- "Launch vehicles – Ariane 5". esa.int. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- "Ariane 5 ES". ESA. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- "Launch vehicle Ariane 5 ME". esa.int. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- "Liftoff! Soyuz begins its maiden mission from the Spaceport". 21 October 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- "Russia ships Soyuz carrier rockets to Kourou spaceport". RIA Novosti. 7 November 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "ESA's new Vega launcher scores success on maiden flight". Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Vega". Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- "Vega – Launch Vehicle". ESA. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- "VEGA – A European carrier for small satellites". ASI. 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014.

-

Svitak, Amy (10 March 2014). "SpaceX Says Falcon 9 To Compete For EELV This Year". Aviation Week. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

ESA Director General Jean-Jacques Dordain is aiming to reduce the agency's development and operational costs in a stark departure from past practice: Until now, the Ariane family of rockets has been built largely with money contributed by ESA governments seeking to participate in the program rather than through competitive industry bids. This means governments commit multiyear funding to the development with the expectation of a roughly 90% return on investment in the form of industrial workshare. But in July, when Dordain presents ESA's member states with industry proposals for building the Ariane 6, he will seek government contributions based on the best value for money, not geographic return on investment. 'To have competitive launchers, we need to rethink the launch sector in Europe.'

- "Closing in on new astronauts". European Space Agency. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- McKie, Robin (22 May 2005). "Europe to hitch space ride on Russia's rocket". The Observer.

- Coppinger, Rob. "EADS Astrium wins €21 million reentry vehicle study". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- Robin McKie (17 November 2012). "Project Orion raises hopes that Britain could have its own man on the moon". The Observer. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Clark, Stephen (8 January 2014). "Europe eyes cooperation on Dream Chaser space plane". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- "One docking ring to rule them all". ESA. 3 June 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- "ESA and Argentina sign extension of Cooperation Agreement". European Space Agency. 20 May 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "ESA on the world stage – international agreements with Brazil, Poland and India". European Space Agency. 1 February 2002. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Closer relations between ESA and China". Space Daily. 21 November 2005. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Agreement signed for European instruments on Chandrayaan-1". European Space Agency. 1 July 2005. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Agreements 2003". ESA Annual Report 2003 (PDF). European Space Agency. pp. 112–113.

- esa. "ESA signs Cooperation Agreement with Turkey". European Space Agency. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- "ESA and the EU". European Space Agency. 9 October 2008.

- Millett, Lucy (29 August 2009). "Opening up the gate to space". Cyprus Mail. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- "Former astronaut MEP backs Europe's stellar ambitions". European Parliament. 28 November 2008. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- Coppinger, Rob (14 October 2009). "2010 to see European Union human spaceflight decision". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- "Space exploration: European Ministers in Prague prepare a roadmap towards a common vision". European Space Agency. 14 October 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- European Space Policy and Programs Handbook. International Business Publications. 2013. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4330-1532-8.

- An interview with David Southwood, ESA Science Director (Video). Space.co.uk. 29 March 2008.

- "Why Europe's astronauts are learning Chinese". BBC News. 26 June 2018.

- "David Southwood at the 2008 UK Space Conference". Space.co.uk. 29 March 2008. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008.

- "Russian, European space agencies to team up for Mars mission | RIA Novosti". En.rian.ru. 17 August 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- "International Space Station legal framework". European Space Agency. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "International Space Station: How much does it cost?". European Space Agency. 9 August 2005. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) Utilisation Relevant Data Rev. 1.2" (PDF). ESA ERASMUS User Centre.

- "Contact ESAC". European Space Agency. 14 October 2009.

- "Esa opens its doors in uk" (Press release). European Space Agency. 14 May 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- esa. "ESA and the EU". European Space Agency. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- "Bomb Shatters Office of Europe Space Unit". The New York Times.

- https://www.hackread.com/anonymous-hacks-european-space-agency-domains/

Further reading

| Library resources about European Space Agency |

- ESA Bulletin () is a quarterly magazine about the work of ESA that can be subscribed to free of charge.

- Bonnet, Roger; Manno, Vittorio (1994). International Cooperation in Space: The Example of the European Space Agency (Frontiers of Space). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-45835-4.

- Johnson, Nicholas (1993). Space technologies and space science activities of member states of the European Space Agency. OCLC 29768749 .

- Peeters, Walter (2000). Space Marketing: A European Perspective (Space Technology Library). ISBN 0-7923-6744-8.

- Zabusky, Stacia (1995 and 2001). Launching Europe: An Ethnography of European Cooperation in Space Science. ISBN B00005OBX2.

- Harvey, Brian (2003). Europe's Space Programme: To Ariane and Beyond. ISBN 1-85233-722-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to European Space Agency. |

| Wikinews has news related to: |

- Official website

- A European strategy for space – Europa

- Convention for the establishment of a European Space Agency, September 2005

- Convention for the Establishment of a European Space Agency, Annex I: Privileges and Immunities

- European Space Agency fonds and 'Oral History of Europe in Space' project run by the European Space Agency at the Historical Archives of the EU in Florence

- Open access at the European Space Agency

.jpg)

.jpg)