Guinea

Guinea (/ˈɡɪni/ (![]()

Republic of Guinea | |

|---|---|

Location of Guinea (dark blue) – in Africa (light blue & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Conakry 9°31′N 13°42′W |

| Official languages | French |

| Vernacular languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2014[1]) | |

| Demonym(s) | Guinean |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

• President | Alpha Condé |

• Prime Minister | Ibrahima Kassory Fofana |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence | |

• from France | 2 October 1958 |

| Area | |

• Total | 245,857 km2 (94,926 sq mi) (77th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 12,414,293[2][3] (77th) |

• 2014 census | 11,523,261[1] |

• Density | 40.9/km2 (105.9/sq mi) (164th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $26.451 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $2,390[4] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $9.183 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $818[4] |

| Gini (2012) | 33.7[5] medium |

| HDI (2018) | low · 174th |

| Currency | Guinean franc (GNF) |

| Time zone | UTC (GMT) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +224 |

| ISO 3166 code | GN |

| Internet TLD | .gn |

The sovereign state of Guinea is a republic with a president who is directly elected by the people; this position is both head of state and head of government. The unicameral Guinean National Assembly is the legislative body of the country, and its members are also directly elected by the people. The judicial branch is led by the Guinea Supreme Court, the highest and final court of appeal in the country.[12]

Guinea is a predominantly Islamic country, with Muslims representing 85 percent of the population.[7][13][14] Guinea's people belong to twenty-four ethnic groups. French, the official language of Guinea, is the main language of communication in schools, in government administration, and the media, but more than twenty-four indigenous languages are also spoken.

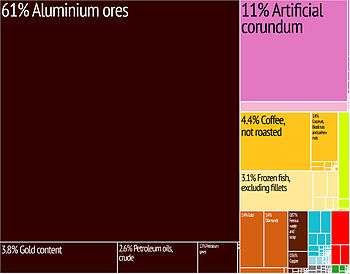

Guinea's economy is largely dependent on agriculture and mineral production.[15] It is the world's second largest producer of bauxite, and has rich deposits of diamonds and gold.[16] The country was at the core of the 2014 Ebola outbreak. Human rights in Guinea remain a controversial issue. In 2011 the United States government claimed that torture by security forces, and abuse of women and children (e.g. female genital mutilation) were ongoing abuses of human rights.[17]

Name

Guinea is named after the Guinea region. Guinea is a traditional name for the region of Africa that lies along the Gulf of Guinea. It stretches north through the forested tropical regions and ends at the Sahel. The English term Guinea comes directly from the Portuguese word Guiné, which emerged in the mid-15th century to refer to the lands inhabited by the Guineus, a generic term for the black African peoples south of the Senegal River, in contrast to the "tawny" Zenaga Berbers above it, whom they called Azenegues or Moors.

History

The land that is now Guinea belonged to a series of African empires until France colonized it in the 1890s, and made it part of French West Africa. Guinea declared its independence from France on 2 October 1958. From independence until the presidential election of 2010, Guinea was governed by a number of autocratic rulers.[18][19][20]

For the origin of the name "Guinea" see Guinea (region) § Etymology.

West African empires and Kingdoms in Guinea

What is now Guinea was on the fringes of the major West African empires. The earliest, the Ghana Empire, grew on trade but ultimately fell after repeated incursions of the Almoravids. It was in this period that Islam first arrived in the region by way of North African traders.

The Sosso kingdom (12th to 13th centuries) briefly flourished in the resulting void but the Mali Empire came to prominence when Soundiata Kéïta defeated the Sosso ruler Soumangourou Kanté at the Battle of Kirina in c. 1235. The Mali Empire was ruled by Mansa (Emperors), the most famous being Kankou Moussa, who made a famous hajj to Mecca in 1324. Shortly after his reign the Mali Empire began to decline and was ultimately supplanted by its vassal states in the 15th century.

The most successful of these was the Songhai Empire, which expanded its power from about 1460 and eventually surpassed the Mali Empire in both territory and wealth. It continued to prosper until a civil war over succession followed the death of Askia Daoud in 1582. The weakened empire fell to invaders from Morocco at the Battle of Tondibi just three years later. The Moroccans proved unable to rule the kingdom effectively, however, and it split into many small kingdoms.

After the fall of the major West African empires, various kingdoms existed in what is now Guinea. Fulani Muslims migrated to Futa Jallon in Central Guinea and established an Islamic state from 1727 to 1896 with a written constitution and alternate rulers. The Wassoulou or Wassulu empire was a short-lived (1878–1898) empire, led by Samori Toure in the predominantly Malinké area of what is now upper Guinea and southwestern Mali (Wassoulou). It moved to Ivory Coast before being conquered by the French.

Colonial era

The European traders arrived in the 16th century. Slaves were exported to work elsewhere in the triangular trade. The traders exploited the regional slave practices that had existed for centuries of trading in human beings.

Guinea's colonial period began with French military penetration into the area in the mid-19th century. French domination was assured by the defeat in 1898 of the armies of Samori Touré, Mansa (or Emperor) of the Ouassoulou state and leader of Malinké descent, which gave France control of what today is Guinea and adjacent areas.

France negotiated Guinea's present boundaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the British for Sierra Leone, the Portuguese for their Guinea colony (now Guinea-Bissau), and Liberia. Under the French, the country formed the Territory of Guinea within French West Africa, administered by a governor general resident in Dakar. Lieutenant governors administered the individual colonies, including Guinea.

Independence and post-colonial rule (1958–2008)

In 1958, the French Fourth Republic collapsed due to political instability and its failures in dealing with its colonies, especially Indochina and Algeria. The founding of a Fifth Republic was supported by the French people, while French President Charles de Gaulle made it clear on 8 August 1958 that France's colonies were to be given a stark choice between more autonomy in a new French Community or immediate independence in the referendum to be held on 28 September 1958. The other colonies chose the former but Guinea—under the leadership of Ahmed Sékou Touré whose Democratic Party of Guinea-African Democratic Rally (PDG) had won 56 of 60 seats in 1957 territorial elections – voted overwhelmingly for independence. The French withdrew quickly, and on 2 October 1958, Guinea proclaimed itself a sovereign and independent republic, with Sékou Touré as president.

.jpg)

In response to the vote for independence, the French settlers in Guinea were quite dramatic in severing ties with Guinea. The Washington Post observes how brutal the French were in tearing down all what they thought was their contributions to Guinea: "In reaction, and as a warning to other French-speaking territories, the French pulled out of Guinea over a two-month period, taking everything they could with them. They unscrewed lightbulbs, removed plans for sewage pipelines in Conakry, the capital, and even burned medicines rather than leave them for the Guineans."[21]

Guinea subsequently quickly aligned itself with the Soviet Union and adopted socialist policies. This alliance was short-lived, however, as Guinea moved towards a Chinese model of socialism. Despite this, however, the country continued to receive investment from capitalist countries such as the United States. By 1960, Touré had declared the PDG the country's only legal political party and for the next 24 years, the government and the PDG were one. Touré was reelected unopposed to four seven-year terms as president, and every five years voters were presented with a single list of PDG candidates for the National Assembly. Advocating a hybrid African Socialism domestically and Pan-Africanism abroad, Touré quickly became a polarising leader, and his government became intolerant of dissent, imprisoning thousands and stifling the press.

Throughout the 1960s the Guinean government nationalised land, removed French-appointed and traditional chiefs from power, and had strained ties with the French government and French companies. Touré's government relied on the Soviet Union and China for infrastructure aid and development but much of this was used for political and not economic purposes (such as the building of large stadiums to hold political rallies). Meanwhile, the country's roads, railways and other infrastructure languished and the economy stagnated.

On 22 November 1970, Portuguese forces from neighboring Portuguese Guinea staged Operation Green Sea, a raid on Conakry by several hundred exiled Guinean opposition forces. Among their goals, the Portuguese military wanted to kill or capture Sekou Toure due his support of the PAIGC, an independence movement and rebel group that carried out attacks inside Portuguese Guinea from their bases in Guinea.[22] After fierce fighting, the Portuguese-backed forces retreated, having freed several dozen Portuguese prisoners of war that were being held by the PAIGC in Conakry but without having ousted Touré. In the years after the raid, massive purges were carried out by the Touré government and at least 50,000 people (1% of Guinea's entire population) were killed. Countless others were imprisoned, faced torture, or, often in the case of foreigners, were forced to leave the country (sometimes after having had their Guinean spouse arrested and their children placed into state custody).

A declining economy, mass killings, a stifling political atmosphere, and a ban on all private economic transactions led in 1977 to the "Market Women's Revolt", anti-government riots that were started by women working in Conakry's Madina Market. This caused Touré to make major reforms. Touré vacillated from supporting the Soviet Union to supporting the United States. The late 1970s and early 1980s saw some economic reforms but Touré's centralized control of the state remained. Even the relationship with France improved; after the election of Valéry Giscard d'Estaing as French president, trade increased and the two countries exchanged diplomatic visits.

Sékou Touré died on 26 March 1984 after a heart operation in the United States, and was replaced by Prime Minister Louis Lansana Beavogui, who was to serve as interim president pending new elections. The PDG was due to elect a new leader on 3 April 1984. Under the constitution, that person would have been the only candidate for president. However, hours before that meeting, Colonels Lansana Conté and Diarra Traoré seized power in a bloodless coup. Conté assumed the role of president, with Traoré serving as prime minister until December.

Conté immediately denounced the previous regime's record on human rights, released 250 political prisoners and encouraged approximately 200,000 more to return from exile. He also made explicit the turn away from socialism. This did little to alleviate poverty and the country showed no immediate signs of moving towards democracy.

In 1992, Conté announced a return to civilian rule, with a presidential poll in 1993 followed by elections to parliament in 1995 (in which his party—the Party of Unity and Progress—won 71 of 114 seats.) Despite his stated commitment to democracy, Conté's grip on power remained tight. In September 2001, the opposition leader Alpha Condé was imprisoned for endangering state security, though he was pardoned 8 months later. He subsequently spent a period of exile in France.

In 2001, Conté organized and won a referendum to lengthen the presidential term and in 2003 began his third term after elections were boycotted by the opposition. In January 2005, Conté survived a suspected assassination attempt while making a rare public appearance in the capital Conakry. His opponents claimed that he was a "tired dictator"[23] whose departure was inevitable, whereas his supporters believed that he was winning a battle with dissidents. Guinea still faces very real problems and according to Foreign Policy is in danger of becoming a failed state.[24]

In 2000, Guinea became embroiled in the instability which had long blighted the rest of West Africa as rebels crossed the borders with Liberia and Sierra Leone and it seemed for a time that the country was headed for civil war.[25] Conté blamed neighbouring leaders for coveting Guinea's natural resources, though these claims were strenuously denied.[26] In 2003, Guinea agreed to plans with her neighbours to tackle the insurgents. In 2007, there were large protests against the government, resulting in the appointment of a new prime minister.[27]

Recent history

Conté remained in power until his death on 23 December 2008[28] and several hours following his death, Moussa Dadis Camara seized control in a coup, declaring himself head of a military junta.[29] Protests against the coup became violent and 157 people were killed when, on 28 September 2009, the junta ordered its soldiers to attack people who had gathered to protest against Camara's attempt to become president.[30] The soldiers went on a rampage of rape, mutilation, and murder which caused many foreign governments to withdraw their support for the new regime.[31]

On 3 December 2009, an aide shot Camara during a dispute over the rampage in September. Camara went to Morocco for medical care.[31][32] Vice-President (and defense minister) Sékouba Konaté flew back from Lebanon to run the country in Camara's absence.[33] After meeting in Ouagadougou on 13 and 14 January 2010, Camara, Konaté and Blaise Compaoré, President of Burkina Faso, produced a formal statement of twelve principles promising a return of Guinea to civilian rule within six months.[34]

The presidential election was held on 27 June,[35][36] with a second election held on 7 November due to allegations of electoral fraud.[37] Voter turnout was high, and the elections went relatively smoothly.[38] Alpha Condé, leader of the opposition party Rally of the Guinean People (RGP), won the election promising to reform the security sector and review mining contracts.[39]

In late February 2013, political violence erupted in Guinea after protesters took to the streets to voice their concerns over the transparency of the upcoming May 2013 elections. The demonstrations were fueled by the opposition coalition's decision to step down from the electoral process in protest at the lack of transparency in the preparations for elections.[40] Nine people were killed during the protests, and around 220 were injured. Many of the deaths and injuries were caused by security forces using live ammunition on protesters.[41][42]

The political violence also led to inter-ethnic clashes between the Fula and Malinke, the base of support for President Condé. The former mainly supported the opposition.[43]

On 26 March 2013, the opposition party backed out of the negotiations with the government over the upcoming 12 May election. The opposition said that the government had not respected them, and had not kept any promises they agreed to.[44]

On 25 March 2014, the World Health Organization said that Guinea's Ministry of Health had reported an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Guinea. This initial outbreak had a total of 86 cases, including 59 deaths. By 28 May, there were 281 cases, with 186 deaths.[45] It is believed that the first case was Emile Ouamouno, a 2-year-old boy who lived in the village of Meliandou. He fell ill on 2 December 2013 and died on 6 December.[46][47] On 18 September 2014, eight members of an Ebola education health care team were murdered by villagers in the town of Womey.[48] As of 1 November 2015, there have been 3,810 cases and 2,536 deaths in Guinea.[49]

Government and politics

The country is a republic. The president is directly elected by the people and is head of state and head of government. The unicameral National Assembly is the legislative body of the country, and its members are directly elected by the people. The judicial branch is led by the Guinea Supreme Court, the highest and final court of appeal in the country.[12]

Guinea is a member of many international organizations including the African Union, Agency for the French-Speaking Community, African Development Bank, Economic Community of West African States, World Bank, Islamic Development Bank, IMF, and the United Nations.

Political culture

President Alpha Condé derives support from Guinea's second-largest ethnic group, the Malinke.[50] Guinea's opposition is backed by the Fula ethnic group,[51] who account for around 32 percent of the population.[50]

Executive branch

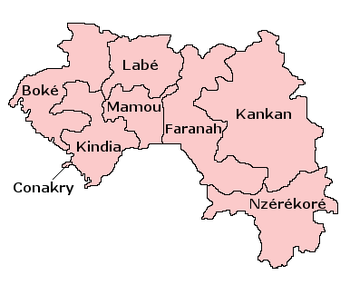

The president of Guinea is normally elected by popular vote for a five-year term; the winning candidate must receive a majority of the votes cast to be elected president. The president governs Guinea, assisted by a council of 25 civilian ministers appointed by him. The government administers the country through eight regions, 33 prefectures, over 100 subprefectures, and many districts (known as communes in Conakry and other large cities and villages or "quartiers" in the interior). District-level leaders are elected; the president appoints officials to all other levels of the highly centralized administration.

Since the 2010 presidential elections, the head of state has been Alpha Condé.

Legislative branch

The National Assembly of Guinea, the country's legislative body, did not meet from 2008 to 2013 when it was dissolved after the military coup in December. Elections have been postponed many times since 2007. In April 2012, President Condé postponed the elections indefinitely, citing the need to ensure that they were "transparent and democratic".[52]

The 2013 Guinean legislative election were held on 24 September 2013.[53] President Alpha Condé's party, the Rally of the Guinean People (RPG), won a plurality of seats in the National Assembly of Guinea, with 53 out of 114 seats. The opposition parties won a total of 53 seats, and opposition leaders denounced the official results as fraudulent.

Foreign relations

_2.jpg)

Guinea's foreign relations, including those with its West African neighbors, have improved steadily since 1985.[54]

Military

Guinea's armed forces are divided into five branches – army, navy, air force, the paramilitary National Gendarmerie and the Republican Guard – whose chiefs report to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who is subordinate to the Minister of Defense. In addition, regime security forces include the National Police Force (Sûreté National). The Gendarmerie, responsible for internal security, has a strength of several thousand.

The army, with about 15,000 personnel, is by far the largest branch of the armed forces. It is mainly responsible for protecting the state borders, the security of administered territories, and defending Guinea's national interests. Air force personnel total about 700. The force's equipment includes several Russian-supplied fighter planes and transports. The navy has about 900 personnel and operates several small patrol craft and barges.

Geography

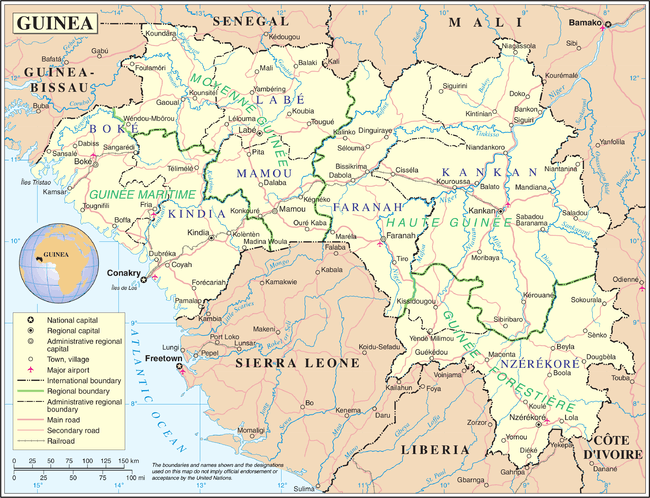

Guinea shares a border with Guinea-Bissau to the north-west, Senegal to the north, Mali to the north-east, Ivory Coast to the east, Sierra Leone to the south-west and Liberia to the south. The nation forms a crescent as it curves from its southeast region to the north and west, to its northwest border with Guinea-Bissau and southwestern coast on the Atlantic Ocean. The sources of the Niger River, Gambia River, and Senegal River are all found in the Guinea Highlands.[55][56][57]

At 245,857 km2 (94,926 sq mi), Guinea is roughly the size of the United Kingdom. There are 320 km (200 mi) of coastline and a total land border of 3,400 km (2,100 mi). It lies mostly between latitudes 7° and 13°N, and longitudes 7° and 15°W (a small area is west of 15°).

Guinea is divided into four main regions: Maritime Guinea, also known as Lower Guinea or the Basse-Coté lowlands, populated mainly by the Susu ethnic group; the cooler, mountainous Fouta Djallon that run roughly north–south through the middle of the country, populated by Fulas, the Sahelian Haute-Guinea to the northeast, populated by Malinké, and the forested jungle regions in the southeast, with several ethnic groups. Guinea's mountains are the source for the Niger, the Gambia, and Senegal Rivers, as well as the numerous rivers flowing to the sea on the west side of the range in Sierra Leone and Ivory Coast.

The highest point in Guinea is Mount Nimba at 1,752 m (5,748 ft). Although the Guinean and Ivorian sides of the Nimba Massif are a UNESCO Strict Nature Reserve, the portion of the so-called Guinean Backbone continues into Liberia, where it has been mined for decades; the damage is quite evident in the Nzérékoré Region at 7°32′17″N 8°29′50″W.

Regions and prefectures

The Republic of Guinea covers 245,857 square kilometres (94,926 sq mi) of West Africa, about 10 degrees north of the equator. Guinea is divided into four natural regions with distinct human, geographic, and climatic characteristics:

- Maritime Guinea (La Guinée Maritime) covers 18% of the country.

- Middle Guinea (La Moyenne-Guinée) covers 20% of the country.

- Upper Guinea (La Haute-Guinée) covers 38% of the country.

- Forested Guinea (Guinée forestière) covers 23% of the country, and is both forested and mountainous.

Guinea is divided into eight administrative regions and subdivided into thirty-three prefectures. Conakry is Guinea's capital, largest city, and economic centre. Nzérékoré, located in the Guinée forestière region in Southern Guinea, is the second largest city.

Other major cities in the country with a population above 100,000 include Kankan, Kindia, Labe, Guéckédou, Boke, Mamou and Kissidougou.

- The capital Conakry with a population of 1,667,864 ranks as a special zone.

| Region | Capital | Population (2014 census) |

|---|---|---|

| Conakry Region | Conakry | 1,667,864 |

| Nzérékoré Region | Nzérékoré | 1,663,582 |

| Kankan Region | Kankan | 1,986,329 |

| Kindia Region | Kindia | 1,559,185 |

| Boké Region | Boké | 1,081,445 |

| Labé Region | Labé | 995,717 |

| Faranah Region | Faranah | 942,733 |

| Mamou Region | Mamou | 732,117 |

Wildlife

The wildlife of Guinea is very diverse due to the wide variety of different habitats. The southern part of the country lies within Guinean Forests of West Africa Biodiversity hotspot, while the north-east is characterized by dry savanna woodlands. Unfortunately, declining populations of large animals are restricted to uninhabited distant parts of parks and reserves.

Taxonomy

Species found in Guinea include the following:

- Amphibians : Hemisus guineensis, Phrynobatrachus guineensis

- Reptiles : Acanthodactylus guineensis, Mochlus guineensis

- Arachnids: Malloneta guineensis, Dictyna guineensis

- Insects : Zorotypus guineensis, Euchromia guineensis

- Birds: Melaniparus guineensis

Economy

Natural resources

Guinea has abundant natural resources including 25% or more of the world's known bauxite reserves. Guinea also has diamonds, gold, and other metals. The country has great potential for hydroelectric power. Bauxite and alumina are currently the only major exports. Other industries include processing plants for beer, juices, soft drinks and tobacco. Agriculture employs 80% of the nation's labor force. Under French rule, and at the beginning of independence, Guinea was a major exporter of bananas, pineapples, coffee, peanuts, and palm oil. Guinea has considerable potential for growth in the agricultural and fishing sectors. Soil, water, and climatic conditions provide opportunities for large-scale irrigated farming and agro industry.

Mining

Guinea possesses over 25 billion tonnes (metric tons) of bauxite – and perhaps up to one-half of the world's reserves. In addition, Guinea's mineral wealth includes more than 4-billion tonnes of high-grade iron ore, significant diamond and gold deposits, and undetermined quantities of uranium. Possibilities for investment and commercial activities exist in all these areas, but Guinea's poorly developed infrastructure and rampant corruption continue to present obstacles to large-scale investment projects.[58]

Joint venture bauxite mining and alumina operations in northwest Guinea historically provide about 80% of Guinea's foreign exchange. Bauxite is refined into alumina, which is later smelted into aluminium. The Compagnie des Bauxites de Guinea (CBG), which exports about 14 million tonnes of high-grade bauxite annually, is the main player in the bauxite industry. CBG is a joint venture, 49% owned by the Guinean government and 51% by an international consortium known as Halco Mining Inc., itself a joint venture controlled by aluminium producer Alcoa (AA), global miner Rio Tinto Group and Dadco Investments.[59] CBG has exclusive rights to bauxite reserves and resources in north-western Guinea through 2038.[60] In 2008 protesters upset about poor electrical services blocked the tracks CBG uses. Guineau often includes a proviso in its agreements with international oil companies requiring its partners to generate power for nearby communities.[61]

The Compagnie des Bauxites de Kindia (CBK), a joint venture between the government of Guinea and RUSAL, produces some 2.5 million tonnes annually, nearly all of which is exported to Russia and Eastern Europe. Dian Dian, a Guinean/Ukrainian joint bauxite venture, has a projected production rate of 1,000,000 t (1,102,311 short tons; 984,207 long tons) per year, but is not expected to begin operation for several years. The Alumina Compagnie de Guinée (ACG), which took over the former Friguia Consortium, produced about 2.4 million tonnes in 2004 as raw material for its alumina refinery. The refinery exports about 750,000 tonnes of alumina. Both Global Alumina and Alcoa-Alcan have signed conventions with the government of Guinea to build large alumina refineries with a combined capacity of about 4 million tonnes per year.

Diamonds and gold also are mined and exported on a large scale. The bulk of diamonds are mined artisanally. The largest gold mining operation in Guinea is a joint venture between the government and Ashanti Goldfields of Ghana. AREDOR, a joint diamond-mining venture between the Guinean Government (50%) and an Australian, British, and Swiss consortium, began production in 1984 and mined diamonds that were 90% gem quality. Production stopped from 1993 until 1996, when First City Mining of Canada purchased the international portion of the consortium. Société Minière de Dinguiraye (SMD) also has a large gold mining facility in Lero, near the Malian border.

Oil

Guinea signed a production sharing agreement with Hyperdynamics Corporation of Houston in 2006 to explore a large offshore tract, and was recently in partnership with Dana Petroleum PLC (Aberdeen, United Kingdom). The initial well, the Sabu-1, was scheduled to begin drilling in October 2011 at a site in approximately 700 meters of water. The Sabu-1 targeted a four-way anticline prospect with upper Cretaceous sands and was anticipated to be drilled to a total depth of 3,600 meters.[62]

Following the completion of exploratory drilling in 2012, the Sabu-1 well was not deemed commercially viable.[63] In November 2012, Hyperdynamics subsidiary SCS reached an agreement for a sale of 40% of the concession to Tullow Oil, bringing ownership shares in the Guinea offshore tract to 37% Hyperdynamics, 40% Tullow Oil, and 23% Dana Petroleum.[64] Hyperdynamics will have until September 2016 under the current agreement to begin drilling its next selected site, the Fatala Cenomanian turbidite fan prospect.[65][66]

Agriculture

The majority of Guineans work in the agriculture sector, which employs approximately 75% of the country. The rice is cultivated in the flooded zones between streams and rivers. However, the local production of rice is not sufficient to feed the country, so rice is imported from Asia. The agriculture sector of Guinea cultivates coffee beans, pineapples, peaches, nectarines, mangoes, oranges, bananas, potatoes, tomatoes, cucumbers, pepper, and many other types of produce. Guinea is one of the emerging regional producers of apples and pears. There are many plantations of grapes, pomegranates, and recent years have seen the development of strawberry plantations based on the vertical hydroponic system.

Tourism

Due to its diverse geography, Guinea presents some interesting tourist sites. Among the top attractions are the waterfalls found mostly in the Basse Guinee (Lower Guinea) and Moyenne Guinee (Middle Guinea) regions. The Soumba cascade at the foot of Mount Kakoulima in Kindia, Voile de la Mariée (bride's veil) in Dubreka, the Kinkon cascades that are about 80 m (260 ft) high on the Kokoula River in the prefecture of Pita, the Kambadaga falls that can reach 100 m (330 ft) during the rainy season on the same river, the Ditinn & Mitty waterfalls in Dalaba, and the Fetoré waterfalls and the stone bridge in the region of Labe are among the most well-known water-related tourist sites.

Problems and reforms

In 2002, the IMF suspended Guinea's Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) because the government failed to meet key performance criteria. In reviews of the PRGF, the World Bank noted that Guinea had met its spending goals in targeted social priority sectors. However, spending in other areas, primarily defense, contributed to a significant fiscal deficit.[67] The loss of IMF funds forced the government to finance its debts through Central Bank advances. The pursuit of unsound economic policies has resulted in imbalances that are proving hard to correct.

Under then-Prime Minister Diallo, the government began a rigorous reform agenda in December 2004 designed to return Guinea to a PRGF with the IMF. Exchange rates have been allowed to float, price controls on gasoline have been loosened, and government spending has been reduced while tax collection has been improved. These reforms have not reduced inflation, which hit 27% in 2004 and 30% in 2005. Currency depreciation is also a concern. The Guinea franc was trading at 2550 to the dollar in January 2005. It hit 5554 to the dollar by October 2006. In August 2016 that number had reached 9089.

Despite the opening in 2005 of a new road connecting Guinea and Mali, most major roadways remain in poor repair, slowing the delivery of goods to local markets. Electricity and water shortages are frequent and sustained, and many businesses are forced to use expensive power generators and fuel to stay open.

Even though there are many problems plaguing Guinea's economy, not all foreign investors are reluctant to come to Guinea. Global Alumina's proposed alumina refinery has a price tag above $2 billion. Alcoa and Alcan are proposing a slightly smaller refinery worth about $1.5 billion. Taken together, they represent the largest private investment in sub-Saharan Africa since the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline. Also, Hyperdynamics Corporation, an American oil company, signed an agreement in 2006 to develop Guinea's offshore Senegal Basin oil deposits in a concession of 31,000 square miles (80,000 km2); it is pursuing seismic exploration.[68]

On 13 October 2009, Guinean Mines Minister Mahmoud Thiam announced that the China International Fund would invest more than $7bn (£4.5bn) in infrastructure. In return, he said the firm would be a "strategic partner" in all mining projects in the mineral-rich nation. He said the firm would help build ports, railway lines, power plants, low-cost housing and even a new administrative centre in the capital, Conakry.[69] In September 2011, Mohamed Lamine Fofana, the Mines Minister following the 2010 election, said that the government had overturned the agreement by the ex-military junta.[70]

Youth unemployment remains a large problem. Guinea needs an adequate policy to address the concerns of urban youth. One problem is the disparity between their life and what they see on television. For youth who cannot find jobs, seeing the economic power and consumerism of richer countries only serves to frustrate them further.[71]

Mining controversies

Guinea has large reserves of the steel-making raw material, iron ore. Rio Tinto Group was the majority owner of the $6 billion Simandou iron ore project, which it had called the world's best unexploited resource. This project is said to be of the same magnitude as the Pilbara in Western Australia.[72]

In 2017, Och-Ziff Capital Management Group pled guilty to a multi-year bribery scheme, after an investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) led to a trial in the United States and a fine of $412 million.[73] Following this, the SEC also filed a lawsuit in the US against head of Och-Ziff European operations, Michael Cohen,[74][75] for his role in a bribery scheme in the region.[76][77]

In 2009 the government of Guinea gave the northern half of Simandou to BSGR[78] for an $165 million investment in the project and a pledge to spend $1 billion on railways, saying that Rio Tinto wasn't moving into production fast enough. The US Justice Department investigated allegations that BSGR had bribed President Conté's wife to get him the concession,[79] and so did the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the next elected President of Guinea, Alpha Condé, and an assortment of other national and international entities.

In April 2014 the Guinean government cancelled the company's mining rights in Simandou. BSGR has denied any wrongdoing, and in May 2014 sought arbitration over the government of Guinea's decision to expropriate its mining rights.[80] In February 2019, BSGR and Guinean President Alpha Condé agreed to drop all allegations of wrongdoing as well as the pending arbitration case.[81] Under the agreement, BSGR would relinquish rights to Simandou while being allowed to maintain an interest in the smaller Zogota deposit that would be developed by Niron Metals head Mick Davis.[82][83]

In 2010 Rio Tinto signed a binding agreement with Aluminum Corporation of China Limited to establish a joint venture for the Simandou iron ore project.[84] In November 2016, Rio Tinto admitted paying $10.5 million to a close adviser of President Alpha Condé to obtain rights on Simandou.[85] Conde said he knew nothing about the bribe and denied any wrongdoing. However, according to recordings obtained by FRANCE 24, Guinean authorities were aware of the Simandou briberies.[86]

In July 2017, the UK-based anti-fraud regulator, the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) and the Australian Federal Police[87] launched an investigation into Rio Tinto's business practices in Guinea.[88][89]

Further, In November 2016, the former mining minister of Guinea, Mahmoud Thiam, accused head of Rio Tinto's Guinea operation department of offering him a bribe in 2010 to regain Rio Tinto's control over half of the undeveloped Simandou project.

In September 2011, Guinea adopted a new mining code. The law set up a commission to review government deals struck during the chaotic days between the end of dictatorship in 2008 and Condé coming to power.[90]

In September 2015, the French Financial Public Prosecutor's Office launched an investigation into President Alpha Conde's son, Mohamed Alpha Condé.[91] He was charged with embezzlement of public funds and receiving financial and other benefits from French companies that were interested in the Guinean mining industry.[92][93]

In August 2016, son of a former Prime Minister of Gabon, who worked for Och-Ziff's Africa Management Ltd, a subsidiary of the U.S. hedge fund Och-Ziff, was arrested in the US and charged with bribing officials in Guinea, Chad and Niger on behalf of the company to secure mining concessions[94] and gain access to relevant confidential information.[95] The investigation also revealed that he was involved in rewriting Guinea's mining law during President Conde's rule.[96] In December 2016, the US Department of Justice announced that the man pleaded guilty to conspiring to make corrupt payments to government officials in Africa.[95]

According to a Global Witness report, Sable Mining sought iron ore explorations rights to Mount Nimba in Guinea by getting close to Conde towards the 2010 elections, backing his campaign for presidency and bribing his son.[97] These allegations have not been verified yet but in March 2016 Guinean authorities ordered an investigation into the matter.[98]

The Conde government investigated two other contracts as well, one which left Hyperdynamic with a third of Guinea's offshore lease allocations as well as Rusal's purchase of the Friguia Aluminum refinery, in which it said that Rusal greatly underpaid.[99]

Minority and women's rights

Homosexuality is illegal in Guinea.[100] Same sex relations are considered a strong taboo, and the prime minister declared in 2010 that he doesn't consider sexual orientation a legitimate human right.[17]

Guinea has one of the world's highest rates of female genital mutilation according to Anastasia Gage, an associate professor at Tulane University, and Ronan van Rossem, an associate professor at Ghent University,[101] female genital mutilation in Guinea had been performed on more than 98% of women as of 2009.[102] In Guinea almost all cultures, religions, and ethnicities practice female genital mutilation.[102] The 2005 Demographic and Health Survey reported that 96% of women have gone through the operation. Prosecutions of its practitioners are nonexistent.[17]

Transport infrastructure

The railway from Conakry to Kankan ceased operating in the mid-1980s.[103] Domestic air services are intermittent. Most vehicles in Guinea are 20+ years old, and cabs are any four-door vehicle which the owner has designated as being for hire. Locals, nearly entirely without vehicles of their own, rely upon these taxis (which charge per seat) and small buses to take them around town and across the country. There is some river traffic on the Niger and Milo rivers. Horses and donkeys pull carts, primarily to transport construction materials.

Mining operations are expected to start at Simandou before the end of 2015. Rio Tinto Limited plans to build a 650 km railway to transport iron ore from the mine to the coast, near Matakong, for export.[104] Much of the Simandou iron ore is expected to be shipped to China for steel production.[105]

Conakry International Airport is the largest airport in the country, with flights to other cities in Africa as well as to Europe.

Major roads

The major roads of Guinea are the following:

- N1 connects Conakry, Coyah, Kindia, Mamou, Dabola, Kouroussa, and Kankan.

- N2 connects Mamou, Faranah, Kissidougou, Guékédou, Macenta, Nzérékoré, and Lola.

- N4 connects Coyah, Forécariah, and, Farmoreya.

- N5 connects Mamou, Dalaba, Pita, and Labé.

- N6 connects Kissidougou, Kankan, and Siguiri.

- N20 connects Kamsar, Kolaboui, and Boké.

Demography

| Population in Guinea[2][3] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 3.0 | ||

| 2000 | 8.8 | ||

| 2018 | 12.4 | ||

The population of Guinea is estimated at 12.4 million. Conakry, the capital and largest city, is the hub of Guinea's economy, commerce, education, and culture. In 2014, the total fertility rate (TFR) of Guinea was estimated at 4.93 children born per woman.[106]

Urbanization

Languages

The official language of Guinea is French. The most widely spoken language is Pulaar, which was spoken by 34.6% of the population in 2014. The second most spoken language is the Mandinka language, which was spoken by 24.9% of the population in 2014. The third most spoken language is the Susu language, which was spoken by 17.7% of the population in 2014. Other languages spoken in Guinea include Koniaka, Kissi, Kpelle, and other languages, which are spoken by 22.8% of the population altogether in 2014.[1]

Ethnic groups

The population of Guinea comprises about 24 ethnic groups. The Mandinka, also known as Mandingo or Malinké, comprise 24.8%[108] of the population and are mostly found in eastern Guinea concentrated around the Kankan and Kissidougou prefectures.[11] The Fulas or Fulani,[51] comprise 40.1%[108] of the population and are mostly found in the Futa Djallon region.

The Soussou, comprising 15.8% of the population, are predominantly in western areas around the capital Conakry, Forécariah, and Kindia. Smaller ethnic groups make up the remaining 18.3%[108] of the population, including Kpelle, Kissi, Zialo, Toma and others.[11] Approximately 10,000 non-Africans live in Guinea, predominantly Lebanese, French, and other Europeans.[109]

Religion

The population of Guinea is approximately 85 percent Muslim and 8 percent Christian, with 7 percent adhering to indigenous religious beliefs.[110] Much of the population, both Muslim and Christian, also incorporate indigenous African beliefs into their outlook.[110]

The vast majority of Guinean Muslims are adherent to the Sunni tradition of Islam, of Maliki school of jurisprudence, influenced with Sufism.[111] There is also a Shi'a community in Guinea.

Christian groups include Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Baptists, Seventh-day Adventists, and Evangelical groups. Jehovah's Witnesses are active in the country and recognized by the Government. There is a small Baha'i community. There are small numbers of Hindus, Buddhists, and traditional Chinese religious groups among the expatriate community.[112]

There were three days of ethno-religious fighting in the city of Nzerekore in July 2013.[50][113] Fighting between ethnic Kpelle, who are Christian or animist, and ethnic Konianke, who are Muslims and close to the larger Malinke ethnic group, left at least 54 dead.[113] The dead included people who were killed with machetes and burned alive.[113] The violence ended after the Guinea military imposed a curfew, and President Conde made a televised appeal for calm.[113]

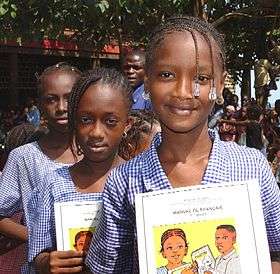

Education

The literacy rate of Guinea is one of the lowest in the world: in 2010 it was estimated that only 41% of adults were literate (52% of males and 30% of females).[114] Primary education is compulsory for 6 years,[115] but most children do not attend for so long, and many do not go to school at all. In 1999, primary school attendance was 40 percent. Children, particularly girls, are kept out of school to assist their parents with domestic work or agriculture,[116] or to be married: Guinea has one of the highest rates of child marriage in the world.[117]

Health

Ebola

In 2014, there was an outbreak of the Ebola virus in Guinea. In response, the health ministry banned the sale and consumption of bats, thought to be carriers of the disease. Despite this measure, the virus eventually spread from rural areas to Conakry,[118] and by late June 2014 had spread to neighboring countries Sierra Leone and Liberia. In early August 2014 Guinea closed its borders to Sierra Leone and Liberia to help contain the spreading of the virus, as more new cases of the disease were being reported in those countries than in Guinea.

The outbreak began in early December, in a village called Meliandou, southeastern Guinea, not far from the borders with both Liberia and Sierra Leone. The first known case was a two-year-old child who died, after fever and vomiting and passing black stool, on 6 December. The child's mother died a week later, then a sister and a grandmother, all with symptoms that included fever, vomiting, and diarrhea. Then, by way of caregiving visits or attendance at funerals, the outbreak spread to other villages.

Unsafe burials remained one of the primary sources of the transmission of the disease. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the inability to engage with local communities hindered the ability of health workers to trace the origins and strains of the virus.[119]

While WHO terminated the Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on 29 March 2016,[120] the Ebola Situation Report released on 30 March confirmed 5 more cases in the preceding two weeks, with viral sequencing relating one of the cases to the November 2014 outbreak.[121]

The epidemic also affected the treatment of other diseases in Guinea. There was a decline in healthcare visits by the population due to fear of being infected and mistrust in the health care system, and a decrease in the system's ability to provide routine health care and HIV/AIDS treatments due to the Ebola outbreak.[122]

Maternal and child healthcare

The 2010 maternal mortality rate per 100,000 births for Guinea is 680. This is compared with 859.9 in 2008 and 964.7 in 1990. The under 5 mortality rate, per 1,000 births is 146 and the neonatal mortality as a percentage of under 5's mortality is 29. In Guinea the number of midwives per 1,000 live births is 1 and the lifetime risk of death for pregnant women is 1 in 26.[123] Guinea has the second highest prevalence of female genital mutilation in the world.[124][125]

HIV/AIDS

An estimated 170,000 adults and children were infected at the end of 2004.[126][127] Surveillance surveys conducted in 2001 and 2002 show higher rates of HIV in urban areas than in rural areas. Prevalence was highest in Conakry (5%) and in the cities of the Forest Guinea region (7%) bordering Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.[128]

HIV is spread primarily through multiple-partner heterosexual intercourse. Men and women are at nearly equal risk for HIV, with young people aged 15 to 24 most vulnerable. Surveillance figures from 2001 to 2002 show high rates among commercial sex workers (42%), active military personnel (6.6%), truck drivers and bush taxi drivers (7.3%), miners (4.7%), and adults with tuberculosis (8.6%).[128]

Several factors are fueling the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Guinea. They include unprotected sex, multiple sexual partners, illiteracy, endemic poverty, unstable borders, refugee migration, lack of civic responsibility, and scarce medical care and public services.[128]

Malnutrition

Malnutrition is a serious problem for Guinea. A 2012 study reported high chronic malnutrition rates, with levels ranging from 34% to 40% by region, as well as acute malnutrition rates above 10% in Upper Guinea's mining zones. The survey showed that 139,200 children suffer from acute malnutrition, 609,696 from chronic malnutrition and further 1,592,892 suffer from anemia. Degradation of care practices, limited access to medical services, inadequate hygiene practices and a lack of food diversity explain these levels.[129]

Culture

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in the country of Guinea.[132] It is run by the Guinean Football Federation.[133] The association administers the national football team, as well as the national league.[132] It was founded in 1960 and affiliated with FIFA since 1962[134] and with the Confederation of African Football since 1963.[135]

The Guinea national football team, nicknamed Syli nationale (National Elephants), have played international football since 1962.[132] Their first opponent was East Germany.[132] They have yet to reach World Cup finals, but they were runners-up to Morocco in the Africa Cup of Nations in 1976.[132]

Guinée Championnat National is the top division of Guinean football. Since it was established in 1965, three teams have dominated in winning the Guinée Coupe Nationale.[136] Horoya AC leads with 16 titles and is the current (2017–2018) champion. Hafia FC (known as Conakry II in 1960s) is second with 15 titles having dominated in 1960s and 70s, but the last coming in 1985. Third with 13 is AS Kaloum Star, known as Conakry I in the 1960s. All three teams are based in the capital, Conakry. No other team has more than five titles.

The 1970s were a golden decade for Guinean football. Hafia FC won the African Cup of Champions Clubs three times, in 1972, 1975 and 1977, while Horoya AC won the 1978 African Cup Winners' Cup.[137]

Polygamy

Polygamy is generally prohibited by law in Guinea, but there are exceptions.[138] UNICEF reports that 53.4% of Guinean women aged 15–49 are in polygamous marriages.[139]

Music

Like other West African countries, Guinea has a rich musical tradition. The group Bembeya Jazz became popular in the 1960s after Guinean independence.

Cuisine

Guinean cuisine varies by region with rice as the most common staple. Cassava is also widely consumed.[140] Part of West African cuisine, the foods of Guinea include jollof rice, maafe, and tapalapa bread. In rural areas, food is eaten from a large serving dish and eaten by hand outside of homes.[141]

References

- "Etat et Structure de la Population Recensement General de la Population et de l'habitation 2014" (PDF). Direction Nationale de la Statistique de Guinée. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Guinea". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". World Bank. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Music Videos of Guinea Conakry". Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2018.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "The Anglican Diocese of Ghana". Netministries.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Nations Online: Guinea – Republic of Guinea – West Africa". Nations Online. Archived from the original on 3 May 2003. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "Guinea's Supreme Court rejects election challenges". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "Religion in Guinea". Visual Geography. Archived from the original on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "The Pan African Bank". Ecobank. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "Guinea Conakry: Major Imports, Exports, Industries & Business Opportunities in Guinea Conakry, Africa". Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "Guinea Conakry Support – Guinee Conakry Trade and Support. (GCTS)". Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (2012). "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2011: Guinea". United States Department of State. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Zounmenou, David (2 January 2009). "Guinea: Hopes for Reform Dashed Again". allAfrica.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- "UN Human Development Report 2009". Hdrstats.undp.org. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- Ross, Will (2 October 2008). "Africa | Guineans mark '50 years of poverty'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 June 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1984/03/28/guineas-longtime-president-ahmed-sekou-toure-dies/18f31685-878c-4759-8028-3bef7fbc568b/

- "Mr Sekou Touré, who gave the PAIGC unstinted support during its war against the Portuguese,..."Black revolt Archived 8 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, The Economist (22 November 1980)

- "Welcome Guinea Forum: Cornered, General Lansana Conte can only hope". Archived from the original on 16 June 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "Failed States list 2008". Fund for Peace. Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- "Civil war fears in Guinea". BBC News. 23 October 2000. Archived from the original on 19 June 2004. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- "Guinea head blames neighbours". BBC News. 6 January 2001. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- "Austrian Study Centre for Peace and Conflict Resolution (ASPR) | Peace Castle Austria" (PDF). ASPR. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- McGreal, Chris (23 December 2008). "Lansana Conté profile: Death of an African 'Big Man'". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Walker, Peter (23 December 2008). "Army steps in after Guinea president Lansana Conté dies". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- "Guinea massacre toll put at 157". London: BBC. 29 September 2009. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- MacFarquhar, Neil (21 December 2009). "U.N. Panel Calls for Court in Guinea Massacre". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- "Guinean soldiers look for ruler's dangerous rival". malaysianews.net. 5 December 2009. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Guinea's presidential guard explains assassination motive Archived 10 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Xinhua News Agency. 16 December 2009.

- "Signature, à Ouagadougou, d'un accord de sortie de crise. (French)". Le Monde. 17 January 2010.

- afrol News – Election date for Guinea proposed Archived 29 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Afrol.com. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Guinea to hold presidential elections in six months _English_Xinhua Archived 10 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. News.xinhuanet.com (16 January 2010). Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "Guinea sets date for presidential run-off vote". BBC News. 9 August 2010. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Guinea sees big turnout in presidential run-off poll", ''BBC'' (7 November 2010) Archived 31 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC.co.uk (7 November 2010). Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Conde declared victorious in Guinea – Africa | IOL News Archived 19 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine. IOL.co.za (16 November 2010). Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "Guinea opposition pulls out of legislative elections process". Reuters. 24 February 2013. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- "Security forces break up Guinea opposition funeral march". Reuters. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- Daniel Flynn (5 March 2013). "Two more killed in Guinea as protests spread". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- "Ethnic Clashes Erupt in Guinea Capital". Voice of America. Reuters. 1 March 2013. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- Bate Felix (26 March 2013). "Guinea election talks fail, opposition threatens protests". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- "Previous Updates: 2014 West Africa Outbreak". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "Ebola: Patient zero was a toddler in Guinea - CNN". CNN. 28 October 2014. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "Ebola Patient Zero: Emile Ouamouno Of Guinea First To Contract Disease". International Business Times. 28 October 2014. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "Arrests Made in Killings of Guinea Ebola Education Team". The Wall Street Journal. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "Ebola Situation Report – 4 November 2015". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 1 December 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ""Guinea's Conde appeals for calm after 11 killed in ethnic clashes", Reuters, 16 July 2013". Reuters. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- In French: Peul. In Fula: Fulɓe.

- RNW Africa Desk (28 April 2012). "Guinea president postpones parliamentary elections indefinitely". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "Guinea election body sets legislative polls for September 24". Reuters. 9 July 2013. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Background Note: Guinea, US Department of State, February 2009

- "The Senegal River basin". Fao.org. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "The Niger River basin". Fao.org. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "The West Coast". Fao.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- 'How a diamond tycoon lost his shine in 'difficult places' A bribery case goes beyond a mine in Guinea' Article by Rachel Millard in The Sunday Times 25 August 2019. Report on huge corruption in Guinea and the trial of diamond mogul Beny Steinmetz in Switzerland, alleging millions of dollars paid in bribes to Madamie Toure, wife of the late Lansana Conte.

- "Guinea bauxite miner CBG plans $1 bln expansion to meet demand". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Saliou Samb; Daniel Magnowski (1 November 2008). "One dead in Guinea protest, mine trains stop". Minesandcommunities.org. Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- "Hyperdynamics Corporation – Jasper Explorer Drill Ship En Route to Hyperdynamics' First Exploration Drilling Site Offshore Guinea". Investors.hyperdynamics.com. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "Hyperdynamics completes drilling at Sabu-1 well offshore Guinea-Conakry". Offshore-technology.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- "Tullow Oil Agrees Farm-in to Guinea Concession". Tullowoil.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- Hyperdynamics. "Overview of the Guinea Project". Hyperdynamics.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- Thomas Adolff; Charlotte Elliott (21 January 2014). "Tullow Oil". Equity Research. Credit Suisse. p. 15. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- International Business Publications, USA. Guinea Investment and Business Guide, Volume 1: Strategic and Practical Information. https://books.google.com/books?id=Wj6zDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false. p. 28.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Joint Venture Opportunity Offshore the West Coast of Africa" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2009.Hyperdynamics Corporation (2008)

- "Guinea confirms huge China deal". BBC News. London. 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- "Guinea mining: PM defends radical industry shake-up". BBC. 14 September 2011. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- Joschka Philipps, "Explosive youth: Focus" Archived 26 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine, D+C (Development and Cooperation), funded by Germany's Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development,(2010/05) pages 190–193]. Inwent.org

- "Mining Weekly – West Africa emerging as new Pilbara as miners race to develop iron-ore projects". Miningweekly.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "U.S. SEC charges two former Och-Ziff executives in bribery case". Reuters. 26 January 2017. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- "Michael Cohen, Once of Och-Ziff, Charged With Fraud by U.S." Bloomberg L.P. 3 January 2018. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- Moyer, Liz (3 January 2018). "Former Och Ziff hedge fund executive indicted for fraud in Africa investment scheme, prosecutor says". CNBC. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- "Two Ex-Och-Ziff Executives Accused by SEC in Bribery Scheme". Bloomberg L.P. 26 January 2017. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- GAN. "SEC charges two 'masterminds' behind Och-Ziff Africa bribe scheme". Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- KHADIJA SHARIFE. "Panama Papers: Steinmetz Guinea deal pried open: Leaked documents pry open the corporate structure of companies involved in a mining rights scandal in Guinea". Times Live. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Patrick Radden Keefe (8 July 2013). "Buried Secrets: How an Israeli billionaire wrested control of one of Africa's biggest prizes". A Reporter at Large. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "UPDATE 2-BSGR starts arbitration against Guinea over lost mining rights". Reuters. 7 May 2017. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "Bloomberg Are you a robot?". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- "Israeli Billionaire Steinmetz's BSGR Settles Guinea Row, Looks to Zogota Iron Ore". Haaretz. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- Goodley, Simon (25 February 2019). "Beny Steinmetz settles dispute with Guinea over iron ore project". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- "Chinalco, Rio Tinto And Russal Are Fighting Over Mining Rights And Power in Guinea". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Samb, Sonali Paul and Saliou. "Rio Tinto suspends senior executive after Guinea investigation". Reuters UK. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "Audio recordings drag Guinea president into mine bribery scandal – France 24". France 24. 1 December 2016. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- AFP. "UK Serious Fraud Office probes Rio Tinto Guinea project". The Citizen. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Staff; Reuters (25 July 2017). "SFO says it is investigating Rio Tinto over Guinea operations". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "UK's SFO says opens investigation into Rio Tinto Group". Reuters. 24 July 2017. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Danny Fortson, "Secret deal threatens big miners" Archived 11 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine ''The Sunday Times'' (3 June 2012)]. Scribd.com (3 June 2012)..

- Agency, Ecofin. "French Justice investigating the lifestyle of the son of Guinean president". Ecofin Agency. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "Enquête sur le fils du président guinéen". Le Parisien. 19 February 2017. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ISSAfrica.org. "Another president's son caught with his hand in the cookie jar? – ISS Africa". ISS Africa. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Stevenson, Alexandra (16 August 2016). "Bribery Arrest May Expose African Mining Rights Scandal Tied to Och-Ziff". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "Gabonese National Pleads Guilty to Foreign Bribery Scheme". Justice.gov. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "U.S. Case into Fixer for Och-Ziff Venture Gets Support in Guinea". Bloomberg L.P. 18 August 2016. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Witness, Global. "The Deceivers". Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "Guinea: Sable Mining Bribery Under Probe". The NEWS (Monrovia). 23 May 2016. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "Guinea targets 3 firms in resource contract review – source". Creamer Media's Mining Weekly. Reuters. 9 November 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- "Here are the 10 countries where homosexuality may be punished by death". The Washington Post. 16 June 2016. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- Van Rossem, R; Gage, AJ (2009). "The effects of female genital mutilation on the onset of sexual activity and marriage in Guinea". Arch Sex Behav. 38 (2): 178–85. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9237-5. PMID 17943434.

- Rossem, R. V.; Gage, A. J. (2009). "The effects of female genital mutilation on the onset of sexual activity and marriage in Guinea". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 38 (2): 178–185. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9237-5. PMID 17943434.

- Amadou Timbo Barry (14 May 2015). "Kankan : Le chemin de fer Conakry-Niger à quand sa réhabilitation ?". Guinee News. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016.

- "GUINEA: SIMANDOU PROJECT GAINS MOMENTUM". Railways Africa. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- "Joint venture for Simandou Guinea, Iron ore, Simandou project, Steel, Steel, BHP Billiton, Chinalco, Rio Tinto, World Bank, Agreement, Joint ventures, Port developments, Rail". Bulkmaterialsinternational.com. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "The World Factbook". Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- http://citypopulation.de/Guinea-Cities.html

- "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- "Guinea". State.gov. 22 November 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "Guinea 2012 International Religious Freedom Report", US State Department, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor.

- Harrow, Kenneth (1983). "A Sufi Interpretation of 'Le Regard du Roi'". Research in African Literatures. 14 (2): 135–164. JSTOR 3818383.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2008: Guinea . United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (29 December 2008). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ""Guinean troops deployed after deadly ethnic clashes", BBC Africa, 17 July 2013". BBC News. 17 July 2013. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "The World Factbook". Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2015: Guinea". United States Department of State. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB) – U.S. Department of Labor Archived 5 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Dol.gov. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- According to the WHO:"The 10 countries with the highest rates of child marriage are: Niger, 75%; Chad and Central African Republic, 68%; India, 66%; Guinea, 63%; Mozambique, 56%; Mali, 55%; Burkina Faso and South Sudan, 52%; and Malawi, 50%." Archived 24 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ebola: Guinea outbreak reaches capital Conakry". BBC. 28 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "Ebola Situation Report – 4 March 2015 | Ebola". apps.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "Ebola is no longer a public health emergency". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "Ebola Situation Report – 30 March 2016 | Ebola". apps.who.int. Archived from the original on 13 June 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "The State of the World's Midwifery". United Nations Population Fund. Archived from the original on 25 December 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- "WHO – Female genital mutilation and other harmful practices". Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change – UNICEF DATA" (PDF). Unicef.org. 22 July 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "Status of HIV/AIDS in Guinea, 2005" (PDF). World Health Organisation. 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- "Epidemiological Fact Sheets: HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Infections, December 2006" (PDF). World Health Organisation. December 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- "Health Profile: Guinea" Archived 13 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine. USAID (March 2005).

- "Enquête nationale nutrition-santé, basée sur la méthodologie SMART, 2011–2012" (PDF). World Food Programme. 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Falola, Toyin; Jean-Jacques, Daniel (14 December 2015). Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. ABC-CLIO. pp. 568–569. ISBN 9781598846669. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- "At a glance: Guinea - Football boosts girls' education". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- "Associations: Guinea". FIFA. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Member Associations: Fédération Guinéenne de Football (FGF)". Confederation of African Football. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Guinea: List of champions". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- Kuhn, Gabriel (15 March 2011). Soccer vs. the State: Tackling Football and Radical Politics. PM Press. p. 33. ISBN 9781604865240.

- Articles 315-319 Archived 21 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Civil Code of the Republic of Guinea (Code Civil de la Republique de Guinee)

- "Early Marriage A Harmful Traditional Practice – A Statistical Exploration" Archived 28 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine UNICEF, 2005, p. 38.

- "Recipes & Cookbooks". Friends of Guinea. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "Eating in the Embassy: Guinean Embassy Brings West African Food To Washington". WAMU. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

External links

- Official website (in French)

- "Guinea". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Guinea from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Guinea at Curlie

- Guinea profile from the BBC News

- Guinea 2008 Summary Trade Statistics

.svg.png)