Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that lasted from the 13th century[1] to 1795,[2] when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia and Austria. The state was founded by the Lithuanians, a polytheistic Baltic tribe from Aukštaitija.[3][4][5]

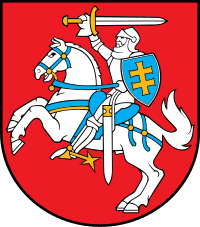

Grand Duchy of Lithuania | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1236–17951 | |||||||||

Supposed appearance of the royal (military) banner with design derived from a 16th century coat of arms

| |||||||||

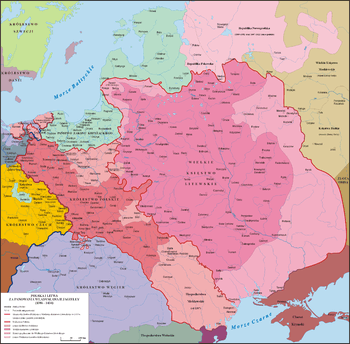

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the height of its power in the 15th century, superimposed on modern borders | |||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||

| Common languages | Lithuanian, Ruthenian, Polish, Latin, German (see § Languages) | ||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||

| Grand Duke | |||||||||

• 1236–1263 (from 1251 as King) | Mindaugas (first) | ||||||||

• 1764–1795 | Stanisław August Poniatowski (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Seimas | ||||||||

• Privy Council | Council of Lords | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Consolidation began | 1180s | ||||||||

| 1251–1263 | |||||||||

| 14 August 1385 | |||||||||

| 1 July 1569 | |||||||||

| 24 October 1795 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1260 | 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 1430 | 930,000 km2 (360,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 1572 | 320,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 1791 | 250,000 km2 (97,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 1793 | 132,000 km2 (51,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1260 | 400,000 | ||||||||

• 1430 | 2,500,000 | ||||||||

• 1572 | 1,700,000 | ||||||||

• 1791 | 2,500,000 | ||||||||

• 1793 | 1,800,000 | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | LT | ||||||||

| |||||||||

1. Unsuccessful Constitution of 3 May 1791 envisioned a unitary state whereby the Grand Duchy would be abolished. | |||||||||

The Grand Duchy expanded to include large portions of the former Kievan Rus' and other neighbouring states, including what is now Belarus and parts of Ukraine, Latvia, Poland and Russia. At its greatest extent, in the 15th century, it was the largest state in Europe.[6] It was a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional state, with great diversity in languages, religion, and cultural heritage.

The consolidation of the Lithuanian lands began in the late 12th century. Mindaugas, the first ruler of the Grand Duchy, was crowned as Catholic King of Lithuania in 1253. The pagan state was targeted in the religious crusade by the Teutonic Knights and the Livonian Order. The rapid territorial expansion started at the late reign of Gediminas[7] and continued to expand under the diarchy and co-leadership of his sons Algirdas and Kęstutis.[8] Algirdas's son Jogaila signed the Union of Krewo in 1386, bringing two major changes in the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: conversion to Christianity and establishment of a dynastic union between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland.[9]

The reign of Vytautas the Great, son of Kęstutis, marked both the greatest territorial expansion of the Grand Duchy and the defeat of the Teutonic Knights in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410. It also marked the rise of the Lithuanian nobility. After Vytautas's death, Lithuania's relationship with the Kingdom of Poland greatly deteriorated.[10] Lithuanian noblemen, including the Radvila family, attempted to break the personal union with Poland.[11] However, unsuccessful wars with the Grand Duchy of Moscow forced the union to remain intact.

Eventually, the Union of Lublin of 1569 created a new state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. In the Federation, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania maintained its political distinctiveness and had separate ministries, laws, army, and treasury.[12] The federation was terminated by the passing of the Constitution of 3 May 1791, when there was supposed to be now a single country, the Commonwealth of Poland, under one monarch, one parliament and no Lithuanian autonomy. Shortly afterward, the unitary character of the state was confirmed by adopting the Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations.

However, the newly reformed Commonwealth was invaded by Russia in 1792 and partitioned between neighbouring states. A truncated state (whose principal cities were Kraków, Warsaw and Vilnius) remained that was nominally independent. After the Kościuszko Uprising, the territory was completely partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia and Austria in 1795.

Etymology

Name of Lithuania (Litua) was first mentioned in 1009 in Annals of Quedlinburg. Some older etymological theories relate the name to a small river not far from Kernavė, the core area of the early Lithuanian state and a possible first capital of the would-be Grand Duchy of Lithuania, is usually credited as the source of the name. This river's original name is Lietava.[13] As time passed, the suffix -ava could have changed into -uva, as the two are from the same suffix branch. The river flows in the lowlands and easily spills over its banks, therefore the traditional Lithuanian form liet- could be directly translated as lietis (to spill), of the root derived from the Proto-Indo-European leyǝ-.[14] However, the river is very small and some find it improbable that such a small and local object could have lent its name to an entire nation. On the other hand, such a fact is not unprecedented in world history.[15] The most credible modern theory of etymology of the name of Lithuania (Lithuanian: Lietuva) is Artūras Dubonis's hypothesis,[16] that Lietuva relates to the word leičiai (plural of leitis, a social group of warriors-knights in the early Grand Duchy of Lithuania). The title of the Grand Duchy was consistently applied to Lithuania from the 14th century onward.[17]

In other languages, the grand duchy is referred to as:

- Belarusian: Вялікае Княства Літоўскае

- German: Großfürstentum Litauen

- Estonian: Leedu Suurvürstiriik

- Latin: Magnus Ducatus Lituaniae

- Latvian: Lieitija or Lietuvas Lielkņaziste

- Lithuanian: Lietuvos Didžioji Kunigaikštystė

- Old literary Lithuanian: Didi Kunigystė Lietuvos

- Polish: Wielkie Księstwo Litewskie

- Russian: Великое княжество Литовское

- Ruthenian: Великое князство Литовское

- Ukrainian: Велике князiвство Литовське

History

Establishment of the state

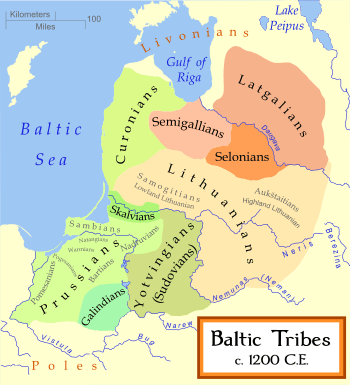

The first written reference to Lithuania is found in the Quedlinburg Chronicle, which dates from 1009.[18] In the 12th century, Slavic chronicles refer to Lithuania as one of the areas attacked by the Rus'. Pagan Lithuanians initially paid tribute to Polotsk, but they soon grew in strength and organized their own small-scale raids. At some point between 1180 and 1183 the situation began to change, and the Lithuanians started to organize sustainable military raids on the Slavic provinces, raiding the Principality of Polotsk as well as Pskov, and even threatening Novgorod.[19] The sudden spark of military raids marked consolidation of the Lithuanian lands in Aukštaitija.[1]

The Livonian Order and Teutonic Knights, crusading military orders, were established in Riga in 1202 and in Prussia in 1226. Lithuanian Crusade was started. The Christian orders posed a significant threat to pagan Baltic tribes and further galvanized the formation of the state. The peace treaty with Galicia–Volhynia of 1219 provides evidence of cooperation between Lithuanians and Samogitians. This treaty lists 21 Lithuanian dukes, including five senior Lithuanian dukes from Aukštaitija (Živinbudas, Daujotas, Vilikaila, Dausprungas and Mindaugas) and several dukes from Žemaitija. Although they had battled in the past, the Lithuanians and the Žemaičiai now faced a common enemy.[20] Likely Živinbudas had the most authority[19] and at least several dukes were from the same families.[21] The formal acknowledgement of common interests and the establishment of a hierarchy among the signatories of the treaty foreshadowed the emergence of the state.

Kingdom of Lithuania

Mindaugas, the duke[22] of southern Lithuania,[23] was among the five senior dukes mentioned in the treaty with Galicia–Volhynia. The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, reports that by the mid-1230s, Mindaugas had acquired supreme power in the whole of Lithuania.[24] In 1236, the Samogitians, led by Vykintas, defeated the Livonian Order in the Battle of Saule. The Order was forced to become a branch of the Teutonic Knights in Prussia, making Samogitia, a strip of land that separated Livonia from Prussia, the main target of both orders. The battle provided a break in the wars with the Knights, and Lithuania exploited this situation, arranging attacks towards the Ruthenian provinces and annexing Navahrudak and Hrodna.[24]

In 1248, a civil war broke out between Mindaugas and his nephews Tautvilas and Edivydas. The powerful coalition against Mindaugas included Vykintas, the Livonian Order, Daniel of Galicia and Vasilko of Volhynia. Taking advantage of internal conflicts, Mindaugas allied with the Livonian Order. He promised to convert to Christianity and to exchange some lands in western Lithuania in return for military assistance against his nephews and the royal crown. In 1251, Mindaugas was baptized and Pope Innocent IV issued a papal bull proclaiming the creation of the Kingdom of Lithuania. After the civil war ended, Mindaugas was crowned as King of Lithuania on 6 July 1253, starting a decade of relative peace. Mindaugas later renounced Christianity and converted back to paganism. Mindaugas tried to expand his influence in Polatsk, a major centre of commerce in the Daugava River basin, and Pinsk.[24] The Teutonic Knights used this period to strengthen their position in parts of Samogitia and Livonia, but they lost the Battle of Skuodas in 1259 and the Battle of Durbe in 1260. This encouraged the conquered Semigallians and Old Prussians to rebel against the Knights.

Encouraged by Treniota, Mindaugas broke the peace with the Order, possibly reverted to pagan beliefs. He hoped to unite all Baltic tribes under the Lithuanian leadership. As military campaigns were not successful, the relationships between Mindaugas and Treniota deteriorated. Treniota, together with Daumantas of Pskov, assassinated Mindaugas and his two sons, Ruklys and Rupeikis, in 1263.[25] The state lapsed into years of internal fighting.

Rise of the Gediminids

From 1263 to 1269, Lithuania had three grand dukes – Treniota, Vaišvilkas, and Švarnas. The state did not disintegrate, however, and Traidenis came to power in 1269. He strengthened Lithuanian control in Black Ruthenia and fought with the Livonian Order, winning the Battle of Karuse in 1270 and the Battle of Aizkraukle in 1279. There is considerable uncertainty about the identities of the grand dukes of Lithuania between his death in 1282 and the assumption of power by Vytenis in 1295. During this time the Orders finalized their conquests. In 1274, the Great Prussian Rebellion ended, and the Teutonic Knights proceeded to conquer other Baltic tribes: the Nadruvians and Skalvians in 1274–1277, and the Yotvingians in 1283; the Livonian Order completed its conquest of Semigalia, the last Baltic ally of Lithuania, in 1291.[26] The Orders could now turn their full attention to Lithuania. The "buffer zone" composed of other Baltic tribes had disappeared, and Grand Duchy of Lithuania was left to battle the Orders on its own.

The Gediminid dynasty ruled the grand duchy for over a century, and Vytenis was the first ruler from the dynasty.[27] During his reign Lithuania engaged in constant warfare with the Order, the Kingdom of Poland, and Ruthenia. Vytenis was involved in succession disputes in Poland, supporting Boleslaus II of Masovia, who was married to a Lithuanian duchess, Gaudemunda. In Ruthenia, Vytenis managed to recapture lands lost after the assassination of Mindaugas and to capture the principalities of Pinsk and Turaŭ. In the struggle against the Order, Vytenis allied with citizens of Riga; securing positions in Riga strengthened trade routes and provided a base for further military campaigns. Around 1307, Polotsk, an important trading centre, was annexed by military force.[28] Vytenis also began the construction of a defensive castle network along the Neman River. Gradually this network developed into the main defensive line against the Teutonic Order.

Territorial expansion

The expansion of the state reached its height under Grand Duke Gediminas, who created a strong central government and established an empire that later spread from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea. In 1320, most of the principalities of western Rus' were either vassalized or annexed by Lithuania. In 1321, Gediminas captured Kiev, sending Stanislav, the last Rurikid to rule Kiev, into exile. Gediminas also re-established the permanent capital of the Grand Duchy in Vilnius, presumably moving it from Old Trakai in 1323.

Lithuania was in a good position to conquer the western and the southern parts of former Kievan Rus'. While almost every other state around it had been plundered or defeated by the Mongols, the hordes stopped at the modern borders of Belarus, and the core territory of the Grand Duchy was left mostly untouched. The weak control of the Mongols over the areas they had conquered allowed the expansion of Lithuania to accelerate. Rus' principalities were never incorporated directly into the Golden Horde, maintaining vassal relationships with a fair degree of independence. Lithuania annexed some of these areas as vassals through diplomacy, as they exchanged rule by the Mongols or the Grand Prince of Moscow with rule by the Grand Duchy. An example is Novgorod, which was often in the Lithuanian sphere of influence and became an occasional dependency of the Grand Duchy.[29] Lithuanian control resulted from internal frictions within the city, which attempted to escape submission to Muscovy. Such relationships could be tenuous, however, as changes in a city's internal politics could disrupt Lithuanian control, as happened on a number of occasions with Novgorod and other East-Slavic cities.

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania managed to hold off Mongol incursions and eventually secured gains. In 1333 and 1339, Lithuanians defeated large Mongol forces attempting to regain Smolensk from the Lithuanian sphere of influence. By about 1355, the State of Moldavia had formed, and the Golden Horde did little to re-vassalize the area. In 1362, regiments of the Grand Duchy army defeated the Golden Horde at the Battle at Blue Waters.[30] In 1380, a Lithuanian army allied with Russian forces to defeat the Golden Horde in the Battle of Kulikovo, and though the rule of the Mongols did not end, their influence in the region waned thereafter. In 1387, Moldavia became a vassal of Poland and, in a broader sense, of Lithuania. By this time, Lithuania had conquered the territory of the Golden Horde all the way to the Dnieper River. In a crusade against the Golden Horde in 1398 (in an alliance with Tokhtamysh), Lithuania invaded northern Crimea and won a decisive victory. In an attempt to place Tokhtamish on the Golden Horde throne in 1399, Lithuania moved against the Horde but was defeated in the Battle of the Vorskla River, losing the steppe region.

Personal Union with Poland

Lithuania was Christianized in 1387, led by Jogaila, who personally translated Christian prayers into the Lithuanian language[31] and his cousin Vytautas the Great who founded many Catholic churches and allocated lands for parishes in Lithuania. The state reached a peak under Vytautas the Great, who reigned from 1392 to 1430. Vytautas was one of the most famous rulers of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, serving as the Grand Duke from 1401 to 1430, and as the Prince of Hrodna (1370–1382) and the Prince of Lutsk (1387–1389). Vytautas was the son of Kęstutis, uncle of Jogaila, who became King of Poland in 1386, and he was the grandfather of Vasili II of Moscow.

In 1410, Vytautas commanded the forces of the Grand Duchy in the Battle of Grunwald. The battle ended in a decisive Polish-Lithuanian victory against the Teutonic Order. The war of Lithuania against military Orders, which lasted for more than 200 years, and was one of the longest wars in the history of Europe, was finally ended. Vytautas backed the economic development of the state and introduced many reforms. Under his rule, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania slowly became more centralized, as the governours loyal to Vytautas replaced local princes with dynastic ties to the throne. The governours were rich landowners who formed the basis for the nobility of the Grand Duchy. During Vytautas' rule, the Radziwiłł and Goštautas families started to gain influence.

The rapid expansion of the influence of Muscovy soon put it into a comparable position as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and after the annexation of Novgorod in 1478, Muscovy was among the preeminent states in northeastern Europe. Between 1492 and 1508, Ivan III further consolidated Muscovy, winning the key Battle of Vedrosha and regaining such ancient lands of Kievan Rus' as Chernihiv and Bryansk.

On 8 September 1514, the allied forces of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Kingdom of Poland, under the command of Hetman Konstanty Ostrogski, fought the Battle of Orsha against the army of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, under Konyushy Ivan Chelyadnin and Kniaz Mikhail Golitsin. The battle was part of a long series of Muscovite–Lithuanian Wars conducted by Russian rulers striving to gather all the former lands of Kievan Rus' under their rule. According to Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii by Sigismund von Herberstein, the primary source for the information on the battle, the much smaller army of Poland–Lithuania (under 30,000 men) defeated the 80,000 Muscovite soldiers, capturing their camp and commander. The Muscovites lost about 30,000 men, while the losses of the Poland–Lithuania army totalled only 500. While the battle is remembered as one of the greatest Lithuanian victories, Muscovy ultimately prevailed in the war. Under the 1522 peace treaty, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania made large territorial concessions.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The wars with Teutonic Order, the loss of land to Moscow, and the continued pressure threatened the survival of the state of Lithuania, so it was forced to ally more closely with Poland, uniting with its western neighbour as the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (Commonwealth of Two Nations) in the Union of Lublin of 1569. During the period of the Union, many of the territories formerly controlled by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were transferred to the Crown of the Polish Kingdom, while the gradual process of Polonization slowly drew Lithuania itself under Polish domination.[32][33][34] The Grand Duchy retained many rights in the federation (including separate ministries, laws, army, and treasury) until the May Constitution of Poland and Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations were passed in 1791.

Partitions and the Napoleonic period

Following the partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, most of the lands of the former Grand Duchy were directly annexed by the Russian Empire, the rest by Prussia. In 1812, just prior to the French invasion of Russia, the former Grand Duchy revolted against the Russians. Soon after his arrival in Vilnius, Napoleon proclaimed the creation of a Commissary Provisional Government of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania which, in turn, renewed the Polish-Lithuanian Union.[35] The union was never formalized, however, as only half a year later Napoleon's Grande Armée was pushed out of Russia and forced to retreat further westwards. In December 1812, Vilnius was recaptured by Russian forces, bringing all plans of recreation of the Grand Duchy to an end.[35] Most of the lands of the former Grand Duchy were re-annexed by Russia. The Augustów Voivodeship (later Augustów Governorate), including the counties of Marijampolė and Kalvarija, was attached to the Kingdom of Poland, a rump state in personal union with Russia.

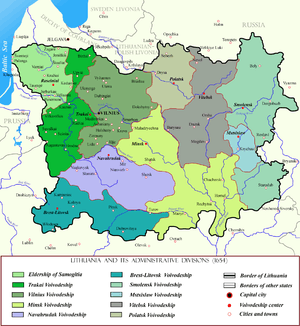

Administrative division

Administrative structure of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (1413–1564).[36]

| Voivodeship (Palatinatus) | Established |

|---|---|

| Vilnius | 1413 |

| Trakai | 1413 |

| Naugardukas | 1507 |

| Brest Litovsk | 1566 |

| Podlaskie | 1514 |

| Minsk | 1566 |

| Smolensk | 1508 |

| Mstislavl | 1569 |

| Polotsk | 1504 |

| Vitebsk | 1511 |

| Kiev | 1471 |

| Volhyn | 1564–1566 |

| Bratslav | 1564 |

| Samogitian eldership | 1413 |

| Duchy of Livonia | 1561 |

Religion and culture

After the baptism in 1252 and coronation of King Mindaugas in 1253, Lithuania was recognized as a Christian state until 1260, when Mindaugas supported an uprising in Courland and (according to the German order) renounced Christianity. Up until 1387, Lithuanian nobles professed their own religion, which was polytheistic. Ethnic Lithuanians were very dedicated to their faith. The pagan beliefs needed to be deeply entrenched to survive strong pressure from missionaries and foreign powers. Until the 17th century, there were relics of old faith reported by counter-reformation active Jesuit priests, like feeding žaltys with milk or bringing food to graves of ancestors. The lands of modern-day Belarus and Ukraine, as well as local dukes (princes) in these regions, were firmly Orthodox Christian (Greek Catholic after the Union of Brest), though. While pagan beliefs in Lithuania were strong enough to survive centuries of pressure from military orders and missionaries, they did eventually succumb. A separate Eastern Orthodox metropolitan eparchy was created sometime between 1315 and 1317 by Constantinople Patriarch John XIII. Following the Galicia–Volhynia Wars which divided Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia between Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Kingdom of Poland, in 1355 the Halych metropoly was liquidated and its eparchies transferred to the metropoles of Lithuania and Volhynia.[38] In 1387, Lithuania converted to Catholicism, while most of the Ruthenian lands stayed Orthodox. At one point, though, Pope Alexander VI reprimanded the Grand Duke for keeping non-Catholics as advisers.[39] There was an effort to polarise Orthodox Christians after the Union of Brest in 1596, by which some Orthodox Christians acknowledged papal authority and Catholic catechism, but preserved their liturgy. The country also became one of the major centres of the Reformation.

In the second half of the 16th century, Calvinism spread in Lithuania, supported by the families of Radziwiłł, Chodkiewicz, Sapieha, Dorohostajski and others. By the 1580s the majority of the senators from Lithuania were Calvinist or Socinian Unitarians (Jan Kiszka).

In 1579, Stephen Báthory, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, founded Vilnius University, one of the oldest universities in Northern Europe. Due to the work of the Jesuits during the Counter-Reformation the university soon developed into one of the most important scientific and cultural centres of the region and the most notable scientific centre of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[40] The work of the Jesuits as well as conversions from among the Lithuanian senatorial families turned the tide and by the 1670s Calvinism lost its former importance though it still retained some influence among the ethnically Lithuanian peasants and some middle nobility.

Languages

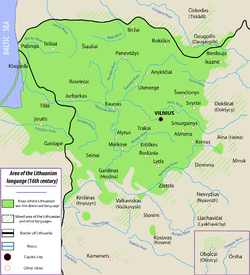

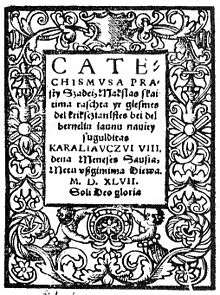

In the 13th century, the centre of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was inhabited by a majority that spoke Lithuanian,[41] though it was not a written language until the 16th century.[42] In the other parts of the duchy, the majority of the population, including Ruthenian nobles and ordinary people, used both spoken and written Ruthenian languages.[41] Nobles who migrated from one place to another would adapt to a new locality and adopt the local religion and culture and those Lithuanian noble families that moved to Slavic areas often took up the local culture quickly over subsequent generations.[43] Ruthenians were native to the east-central and south-eastern parts of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The Ruthenian language, also called Chancery Slavonic in its written form, was used to write laws alongside Polish, Latin and German, but use varied between regions. From the time of Vytautas, there are fewer remaining documents written in Ruthenian than there are in Latin and German, but later Ruthenian became the main language of documentation and writings, especially in eastern and southern parts of the Duchy. In the 16th century at the time of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Lithuanian lands became partially polonized over time and started to use the Polish language for writing much more often than the Lithuanian and Ruthenian languages. Polish finally became the official chancellery language of the Commonwealth in 1697.[43][44][45][46]

The voivodeships with the predominant ethnic Lithuanian population, Vilnius, Trakai, and Samogitian voivodeships, remained almost wholly Lithuanian speaking, both colloquially and by ruling nobility. Ruthenian communities were also present in the extreme southern parts of Trakai voivodeship and south-eastern parts of Vilnius voivodeship. In addition to Lithuanians and Ruthenians, other important ethnic groups throughout the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were Jews and Tatars.[43]

Languages for state and academic purposes

Numerous languages were used in state documents depending on which period in history and for what purpose. These languages included Lithuanian, Ruthenian,[46][47] Polish and, to a lesser extent (mostly in early diplomatic communication), Latin and German.[42][43][45]

The Court used Ruthenian to correspond with Eastern countries while Latin and German were used in foreign affairs with Western countries.[46][48] During the latter part of the history of the Grand Duchy, Polish was increasingly used in State documents, especially after the Union of Lublin.[45] By 1697, Polish had largely replaced Ruthenian as the "official" language at Court,[42][46][49] although Ruthenian continued to be used on a few official documents until the second half of the 18th century.[44]

Usage of the Lithuanian language still continued at Court after the death of Vytautas and Jogaila while Grand Duke Alexander I could understand and speak Lithuanian. Sigismund Augustus maintained both Polish- and Lithuanian-speaking courts.[50]

From the beginning of the 16th century, and especially after a rebellion led by Michael Glinski in 1508, there were attempts by the Court to replace the usage of Ruthenian with Latin.[51] The use of Ruthenian by academics in areas formerly part of Rus' and even in Lithuania proper was widespread. Court Chancellor of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania Lew Sapieha noted in the preface of the Third Statute of Lithuania (1588) that all state documents to be written exclusively in Ruthenian. The same was stated in part 4 of the Statute:

And clerk must use Ruthenian letters and Ruthenian words in all pages, letters and requests, and not any other language or words...

— А писаръ земъский маеть по-руску литерами и словы рускими вси листы, выписы и позвы писати, а не иншимъ езыкомъ и словы..., The Statute of GDL 1588. Part 4, article 1[52]

Despite that, Polish language editions stated the same in Polish language.[53] Statutes of the Grand Duchy were translated into Latin and Polish. One of the main reasons for translations into Latin were that Ruthenian had no well defined and codified law concepts and definitions, which caused many disputes in courts. Another reason to use Latin was a popular idea that Lithuanians were descendants of Romans – mythical house of Palemonids. Augustinus Rotundus translated the Second Statute into Latin.

In 1552, Sigismund II Augustus ordered that orders of the magistrate of Vilnius be announced in Lithuanian, Polish and Ruthenian.

Mikalojus Daukša, writing in the introduction to his Postil (1599) (which was written in Lithuanian) in Polish, advocated the promotion of the Lithuanian language in the Grand Duchy, noting in the introduction that many people, especially szlachta, preferred to speak Polish rather than Lithuanian, but spoke Polish poorly. Such were the linguistic trends in the Grand Duchy that by the political reforms of 1564–1566 parliaments local land courts, appellate courts and other State functions were recorded in Polish,[51] and Polish became increasingly spoken across all social classes.

Lithuanian language situation

Ruthenian and Polish languages were used as state languages of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, besides Latin and German in diplomatic correspondence. Vilnius, Trakai and Samogitia were the core voivodeships of the state, being part of Lithuania Proper, as evidenced by the privileged position of their governors in state authorities, such as the Council of Lords. Peasants in ethnic Lithuanian territories spoke exclusively Lithuanian, except transitional border regions, but the Statutes of Lithuania and other laws and documentation were written in Ruthenian, Latin and Polish. Following the royal court, there was a tendency to replace Lithuanian with Polish in the ethnic Lithuanian areas, whereas Ruthenian was stronger in ethnic Belarusian and Ukrainian territories. There is Sigismund von Herberstein's note left, that there were in an ocean of Ruthenian language in this part of Europe two non-Ruthenian regions: Lithuania and Samogitia.[51]

Since the founding of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the higher strata of Lithuanian society from ethnic Lithuania spoke Lithuanian, although since the later 16th century gradually began using Polish, and from Ruthenia – Ruthenian language. Samogitia was exclusive through state in its economic situation – it lay near ports and there were fewer people under corvee, instead of that, many simple people were money payers. As a result, the stratification of the society was not as sharp as in other areas. Being more similar to a simple population the local szlachta spoke Lithuanian to a bigger extent than in the areas close to the capital Vilnius, which itself had become a centre of intensive linguistic Polonization of surrounding areas since the 18th century.

In Vilnius University there are preserved texts written in the Lithuanian language of the Vilnius area, in a dialect of Eastern Aukštaitian, spoken in a territory lying south-eastwards from Vilnius. The sources are preserved in works of graduates from Stanislovas Rapolionis based Lithuanian language school graduate Martynas Mažvydas and Rapalionis relative Abraomas Kulvietis.

One of the main sources of Lithuanian written in the Eastern Aukštaitian dialect (Vilnius dialect), preserved by Konstantinas Sirvydas in a trilingual (Polish-Latin-Lithuanian) 17th-century dictionary, Dictionarium trium linguarum in usum studiosae juventutis, the main Lithuanian language dictionary used until the late 19th century.

Demographics

In 1260, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was the land of Lithuania, and ethnic Lithuanians formed the majority (67.5%) of its 400,000 people.[54] With the acquisition of new Ruthenian territories, in 1340 this portion decreased to 30%.[55] By the time of the largest expansion towards Rus' lands, which came at the end of the 13th and during the 14th century, the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was 800 to 930 thousand km2, just 10% to 14% of which was ethnically Lithuanian.[54][56]

An estimate of the population in the territory of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania together gives a population at 7.5 million for 1493, breaking them down by ethnicity at 3.75 million Ruthenians (ethnic Ukrainians, Belarusians), 3.25 million Poles and 0.5 million Lithuanians.[57] With the Union of Lublin, 1569, Lithuanian Grand Duchy lost large part of lands to the Polish Crown.

In the mid and late 17th century, due to Russian and Swedish invasions, there was much devastation and population loss on throughout the Grand Duchy of Lithuania,[58] including ethnic Lithuanian population in Vilnius surroundings. Besides devastation, Ruthenian population declined proportionally after the territorial losses to Russian Empire. By 1770 there were about 4.84 million inhabitants in the territory of 320 thousand km2, the biggest part of whom were inhabitants of Ruthenia and about 1.39 million or 29% – of ethnic Lithuania.[54] During the following decades, the population decreased in a result of partitions.[54]

Legacy

Prussian tribes (of Baltic origin) were the subject of Polish expansion, which was largely unsuccessful, so Duke Konrad of Masovia invited the Teutonic Knights to settle near the Prussian area of settlement. The fighting between Prussians and the Teutonic Knights gave the more distant Lithuanian tribes time to unite. Because of strong enemies in the south and north, the newly formed Lithuanian state concentrated most of its military and diplomatic efforts on expansion eastward.

The rest of the former Ruthenian lands were conquered by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Some other lands in Ukraine were vassalized by Lithuania later. The subjugation of Eastern Slavs by two powers created substantial differences between them that persist to this day. While there were certainly substantial regional differences in Kievan Rus', it was the Lithuanian annexation of much of southern and western Ruthenia that led to the permanent division between Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians.

In the 19th century, the romantic references to the times of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were an inspiration and a substantial part of both the Lithuanian and Belarusian national revival movements and Romanticism in Poland.

Notwithstanding the above, Lithuania was a kingdom under Mindaugas, who was crowned by the authority of Pope Innocent IV in 1253. Vytenis, Gediminas and Vytautas the Great also assumed the title of King, although uncrowned by the Pope. A failed attempt was made in 1918 to revive the Kingdom under a German Prince, Wilhelm Karl, Duke of Urach, who would have reigned as Mindaugas II of Lithuania.

In the first half of the 20th century, the memory of the multiethnic history of the Grand Duchy was revived by the Krajowcy movement,[59][60] which included Ludwik Abramowicz (Liudvikas Abramovičius), Konstancja Skirmuntt, Mykolas Römeris (Michał Pius Römer), Józef Albin Herbaczewski (Juozapas Albinas Herbačiauskas), Józef Mackiewicz and Stanisław Mackiewicz.[61][62] This feeling was expressed in poetry by Czesław Miłosz.[62]

Gallery

1.jpg)

Ruins of Navahrudak Castle. Current state (2004)

Ruins of Navahrudak Castle. Current state (2004) Vilnius University and the Church of St. John

Vilnius University and the Church of St. John St. George Church (1487) in Kaunas

St. George Church (1487) in Kaunas Pažaislis Monastery church, decorated with expensive marble

Pažaislis Monastery church, decorated with expensive marble Coins of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Coins of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania Coins of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Coins of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania Coins of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Coins of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania Recreation of the Lithuanian soldiers

Recreation of the Lithuanian soldiers Žemaitukas, a historic horse breed from Lithuania, known from the 6–7th centuries, used as a warhorse by the Lithuanians

Žemaitukas, a historic horse breed from Lithuania, known from the 6–7th centuries, used as a warhorse by the Lithuanians- "Christianization of Lithuania in 1387", oil on canvas by Jan Matejko, 1889, Royal Castle in Warsaw

- Priest, lexicographer Konstantinas Sirvydas, the cherisher of the Lithuanian language in the 17th century

See also

- Cities of Grand Duchy of Lithuania

- Crimea

- History of Lithuania

- List of Belarusian rulers

- List of Lithuanian rulers

- Lithuania

References

- Baranauskas, Tomas (2000). "Lietuvos valstybės ištakos" [The Lithuanian State] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: viduramziu.istorija.net. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- Sužiedėlis, Saulius. Historical dictionary of Lithuania (2nd ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8108-4914-3.

- Rowell S.C. Lithuania Ascending: A pagan empire within east-central Europe, 1295–1345. Cambridge, 1994. p.289-290

- Ch. Allmand, The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge, 1998, p. 731.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. Grand Duchy of Lithuania

- R. Bideleux. A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. Routledge, 1998. p. 122

- Rowell, Lithuania Ascending, p.289.

- Z. Kiaupa. "Algirdas ir LDK rytų politika." Gimtoji istorija 2: Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (Lietuvos istorijos vadovėlis). CD. (2003). Elektroninės leidybos namai: Vilnius.

- N. Davies. Europe: A History. Oxford, 1996, p. 392.

- J. Kiaupienė. Gediminaičiai ir Jogailaičiai prie Vytauto palikimo. Gimtoji istorija 2: Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (Lietuvos istorijos vadovėlis). CD. (2003) Elektroninės leidybos namai: Vilnius.

- J. Kiaupienë, "Valdžios krizës pabaiga ir Kazimieras Jogailaitis." Gimtoji istorija 2: Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (Lietuvos istorijos vadovėlis). CD. (2003). Elektroninės leidybos namai: Vilnius.

- D. Stone. The Polish-Lithuanian state: 1386–1795. University of Washington Press, 2001, p. 63.

- Zigmas Zinkevičius. Kelios mintys, kurios kyla skaitant Alfredo Bumblausko Senosios Lietuvos istoriją 1009-1795m. Voruta, 2005.

- Indo-European Etymology

- Zinkevičius, Zigmas (30 November 1999). "Lietuvos vardo kilmė". Voruta (in Lithuanian). 3 (669). ISSN 1392-0677.

- Dubonis, Artūras (1998). Lietuvos didžiojo kunigaikščio leičiai: iš Lietuvos ankstyvųjų valstybinių struktūrų praeities (Leičiai of Grand Duke of Lithuania: from the past of Lithuanian stative structures (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos instituto leidykla.

- Bojtár, Endre (1999). Foreword to the Past: A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Central European University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-963-9116-42-9.

- "Lithuania". Encarta. 1997. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2006.

- Encyclopedia Lituanica. Boston, 1970–1978, Vol.5 p.395

- Lithuania Ascending p.50

- A. Bumblauskas, Senosios Lietuvos istorija, 1009–1795 [The early history of Lithuania], Vilnius, 2005, p. 33.

- By contemporary accounts, the Lithuanians called their early rulers kunigas (kunigai in plural). The word was borrowed from the German language – kuning, konig. Later on kunigas was replaced by the word kunigaikštis, used to describe to medieval Lithuanian rulers in modern Lithuanian, while kunigas today means priest.

- Z.Kiaupa, J. Kiaupienė, A. Kunevičius. The History of Lithuania Before 1795. Vilnius, 2000. p. 43-127

- V. Spečiūnas. Lietuvos valdovai (XIII-XVIII a.): Enciklopedinis žinynas. Vilnius, 2004. p. 15-78.

- Senosios Lietuvos istorija p. 44-45

- Kiaupa, Zigmantas; Jūratė Kiaupienė; Albinas Kunevičius (2000) [1995]. "Establishment of the State". The History of Lithuania Before 1795 (English ed.). Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History. pp. 45–72. ISBN 9986-810-13-2.

- Lithuania Ascending p. 55

- New Cambridge p. 706

- Hinson, E. Glenn (1995), The Church Triumphant: A History of Christianity Up to 1300, Mercer University Press, p. 438, ISBN 978-0-86554-436-9

- Cherkas, Borys (30 December 2011). Битва на Синіх Водах. Як Україна звільнилася від Золотої Орди [Battle at Blue Waters. How Ukraine freed itself from the Golden Horde] (in Ukrainian). istpravda.com.ua. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- Kloczowski, Jerzy (2000), A History of Polish Christianity, Cambridge University Press, p. 55, ISBN 978-0-521-36429-4

- Makuch, Andrij. "Ukraine: History: Lithuanian and Polish rule". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

Within the [Lithuanian] grand duchy the Ruthenian (Ukrainian and Belarusian) lands initially retained considerable autonomy. The pagan Lithuanians themselves were increasingly converting to Orthodoxy and assimilating into the Ruthenian culture. The grand duchy's administrative practices and legal system drew heavily on Slavic customs, and an official Ruthenian state language (also known as Rusyn) developed over time from the language used in Rus. Direct Polish rule in Ukraine in the 1340s and for two centuries thereafter was limited to Galicia. There, changes in such areas as administration, law, and land tenure proceeded more rapidly than in Ukrainian territories under Lithuania. However, Lithuania itself was soon drawn into the orbit of Poland following the dynastic linkage of the two states in 1385/86 and the baptism of the Lithuanians into the Latin (Roman Catholic) church.

- "Union of Lublin: Poland-Lithuania [1569]". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

Formally, Poland and Lithuania were to be distinct, equal components of the federation,[...] But Poland, which retained possession of the Lithuanian lands it had seized, had greater representation in the Diet and became the dominant partner.

- Stranga, Aivars. "Lithuania: History: Union with Poland". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

While Poland and Lithuania would thereafter elect a joint sovereign and have a common parliament, the basic dual state structure was retained. Each continued to be administered separately and had its own law codes and armed forces. The joint commonwealth, however, provided an impetus for cultural Polonization of the Lithuanian nobility. By the end of the 17th century, it had virtually become indistinguishable from its Polish counterpart.

- Marek Sobczyński. "Procesy integracyjne i dezintegracyjne na ziemiach litewskich w toku dziejów" [The process of integration and disintegration in the territories of Lithuania in the course of events] (PDF) (in Polish). Zakład Geografii Politycznej Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės administracinis teritorinis suskirstymas". vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Vilniaus barokas". vilniausbarokas.weebly.com (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Halych metropoly. Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- von Pastor, Ludwig. The History of the Popes, from the Close of the Middle Ages. 6. p. 146. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

...he wrote to the Grand Duke of Lithuania, admonishing him to do everything in his power to persuade his consort to 'abjure the Russian religion, and accept the Christian Faith.'

- Vilniaus Universitetas. History of Vilnius University. Retrieved on 2007.04.16

- Daniel. Z Stone, A History of East Central Europe, p.4

- O'Connor, Kevin (2006), Culture and Customs of the Baltic States, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 115, ISBN 978-0-313-33125-1, retrieved 12 August 2016

- Burant, S. R.; Zubek, V. (1993). "Eastern Europe's Old Memories and New Realities: Resurrecting the Polish-lithuanian Union". East European Politics & Societies. 7 (2): 370–393. doi:10.1177/0888325493007002007. ISSN 0888-3254.

- Zinkevičius, Zigmas (1995). "Lietuvos Didžiosios kunigaikštystės kanceliarinės slavų kalbos termino nusakymo problema" (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: viduramziu.istorija.net. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Daniel. Z Stone, A History of East Central Europe, p.46

- Wiemer, Björn (2003). "Dialect and language contacts on the territory of the Grand Duchy from the 15th century until 1939". In Kurt Braunmüller; Gisella Ferraresi (eds.). Aspects of Multilingualism in European Language History. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 109–114. ISBN 90-272-1922-2. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Stone, Daniel. The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386–1795. Seattle: University of Washington, 2001. p. 4.

- Kamuntavičius, Rustis. Development of Lithuanian State and Society. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, 2002. p.21.

- Eberhardt, Piotr (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe. M.E. Sharpe. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-7656-1833-7. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Daniel. Z Stone, A History of East Central Europe, p.52

- Dubonis, Artūras (2002). "Lietuvių kalba: poreikis ir vartojimo mastai (XV a. antra pusė – XVI a. antra pusė)" [Lithuanian language: the need for and extent of use (second half XV c. – second half XVI c.)] (in Lithuanian). viduramziu.istorija.net. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- [...] не обчымъ яким языкомъ, але своимъ властнымъ права списаные маемъ [...]; Dubonis, A. Lietuvių kalba

- Statut wielkiego ksiestwa litewskiego. (Statut des Großfürstenthums Lithauen.) (in Polish). 1786. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Letukienė, Nijolė; Gineika, Petras (2003). "Istorija. Politologija: kurso santrauka istorijos egzaminui" (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Alma littera: 182. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). Statistical numbers, usually accepted in historiography (the sources, their treatment, the method of measuring is not discussed in the source), are given, according to which in 1260 there were about 0.27 million Lithuanians out of a total population of 0.4 million (or 67.5%). The size of the territory of the Grand Duchy was about 200 thousand km2. The following data on population is given in the sequence – year, total population in millions, territory, Lithuanian (inhabitants of ethnic Lithuania) part of population in millions: 1340 – 0.7, 350 thousand km2, 0.37; 1375 – 1.4, 700 thousand km2, 0.42; 1430 – 2.5, 930 thousand km2, 0.59 or 24%; 1490 – 3.8, 850 thousand km2, 0.55 or 14% or 1/7; 1522 – 2.365, 485 thousand km2, 0.7 or 30%; 1568 – 2.8, 570 thousand km2, 0.825 million or 30%; 1572, 1.71, 320 thousand km2, 0.85 million or 50%; 1770 – 4.84, 320 thousand km2, 1.39 or 29%; 1791 – 2.5, 250 km2, 1.4 or 56%; 1793 – 1.8, 132 km2, 1.35 or 75% - Letukienė, N., Istorija, Politologija: Kurso santrauka istorijos egzaminui, 2003, p. 182; there were about 0.37 million Lithuanians of 0.7 million of a whole population by 1340 in the territory of 350 thousand km2 and 0.42 million of 1.4 million by 1375 in the territory of 700 thousand km2. Different numbers can also be found, for example: Kevin O'Connor, The History of the Baltic States, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0-313-32355-0, Google Print, p.17. Here the author estimates that there were 9 million inhabitants in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and 1 million of them were ethnic Lithuanians by 1387.

- Wiemer, Björn (2003). "Dialect and language contacts on the territory of the Grand Duchy from the 15th century until 1939". In Kurt Braunmüller; Gisella Ferraresi (eds.). Aspects of Multilingualism in European Language History. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 109, 125. ISBN 90-272-1922-2. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- Pogonowski, Iwo (1989), Poland: A Historical Atlas, Dorset, p. 92, ISBN 978-0-88029-394-5 - Based on 1493 population map

- Kotilaine, J. T. (2005), Russia's Foreign Trade and Economic Expansion in the Seventeenth Century: Windows on the World, BRILL, p. 45, ISBN 90-04-13896-X, retrieved 12 August 2016

- Gil, Andrzej. "Rusini w Rzeczypospolitej Wielu Narodów i ich obecność w tradycji Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego – problem historyczny czy czynnik tworzący współczesność?" [Ruthenians/Rus/Rusyns in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and their presence in the tradition of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania – an historical problem or contemporary creation?] (PDF) (in Polish). Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej (Central and Eastern European Institute). Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- Pawełko-Czajka, Barbara (2014). "The Memory of Multicultural Tradition of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Thought of Vilnius Krajowcy" (PDF). International Congress of Belarusian Studies. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- Gałędek, Michał. "Wielkie Księstwo Litewskie w myśli politycznej Stanisława Cata-Mackiewicza" [The Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Political Thought of Stanisław Cat-Mackiewicz] (in Polish). academia.edu. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- Diena, Kauno; Vaida Milkova (5 May 2011). "Miłosz's Anniversary in the Context of Dumb Politics". Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

Sources

- Norman Davies. God's Playground. Columbia University Press; 2nd edition (2002), ISBN 0-231-12817-7.

- Robert Frost. The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania: Volume I: The Making of the Polish-Lithuanian Union, 1385–1569. Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0198208693

- Alan V. Murray. Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier 1150–1500 (Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought: Fourth Series). Routledge, 2001. ISBN 9780754603252.

- Alan V. Murray. The Clash of Cultures on the Medieval Baltic Frontier Routledge, 2016. ISBN 978-0754664833.

- Zenonas Norkus. An Unproclaimed Empire: The Grand Duchy of Lithuania: From the Viewpoint of Comparative Historical Sociology of Empires, Routledge, 2017, 426 p. ISBN 978-1138281547

- S. C. Rowell. Chartularium Lithuaniae res gestas magni ducis Gedeminne illustrans. Gedimino laiškai. Vilnius, 2003, ISBN 5-415-01700-3. e-copy

- S. C. Rowell. Lithuania Ascending: A Pagan Empire within East-Central Europe, 1295–1345 (Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought: Fourth Series). Cambridge University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1107658769.

- S. C. Rowell, D. Baronas. The conversion of Lithuania. From pagan barbarians to late medieval Christians. Vilnius, 2015, ISBN 9786094251528.

- Daniel Z. Stone. The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386–1795. University of Washington Press. 2014. Pp. xii, 374. ISBN 9780295803623

- A. Dubonis , D. Antanavičius, R. Ragauskiene, R. Šmigelskytė-Štukienė. The Lithuanian Metrica : History and Research. Academic Studies Press. Brighton, United States, 2020. ISBN 9781644693100

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand Duchy of Lithuania. |

- History of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

- Cheryl Renshaw. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania 1253–1795

- Grand Duchy of Lithuania

- Grand Duchy of Lithuania administrative map

- Lithuanian-Ruthenian state at the Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- Zenonas Norkus. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Retrospective of Comparative Historical Sociology of Empires

.svg.png)