Battle of Kircholm

The Battle of Kircholm (27 September 1605, or 17 September in the Old Style calendar then in use in Protestant countries) was one of the major battles in the Polish–Swedish War. The battle was decided in 20 minutes by the devastating charge of Polish–Lithuanian cavalry, the Winged Hussars.[3] The battle ended in the decisive victory of the Polish–Lithuanian forces, and is remembered as one of the greatest triumphs of Commonwealth cavalry.

| Battle of Kircholm | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Polish–Swedish War (1600–1611) | |||||||

A 1630 painting by Pieter Snayers | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Jan Karol Chodkiewicz | Charles IX of Sweden | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

3,600:[1]:64 2,600 cavalry 5 cannons |

10,868:[1]:64 8,368 infantry 11 cannons | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

100 killed, 200 wounded[1]:65 | 7,600–8,000 killed, captured and dispersed[2] | ||||||

History

Eve of the battle

On 27 September 1605, the Commonwealth and Swedish forces met near the small town of Kircholm (now Salaspils in Latvia, some 18 km south east of Riga). The forces of Charles IX of Sweden were numerically superior and were composed of 10,868 men[1]:64 and 11 cannons. The Swedish army included two western commanders, Frederick of Lüneburg and Count Joachim Frederick of Mansfeld,[1]:64 with a few thousand German and Dutch mercenaries and even a few hundred Scots.

The Polish Crown declined to raise funds for defence, although Great Hetman of Lithuania Jan Karol Chodkiewicz promised to pay out army wages from his own fortune, thereby gathering at least some army from Lithuania. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth army under Chodkiewicz was composed of roughly 1,000 infantry and 2,600 cavalry[1]:64 and only five cannons. However, the Polish–Lithuanian forces were well-rested and their cavalry consisted mostly of superbly trained Winged Hussars or heavy cavalry armed with lances, while the Swedish cavalry were less-well trained, armed with pistols and carbines, on poorer horses, and tired after a long night's march over 10 km in torrential rain.[1]:65 The Polish–Lithuanian forces had a small number of Polish cossack light cavalry and Lithuanian tatars light cavalry (cossack and tatar cavalry is a class of light cavalry in Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth at this date not to be confused with the Ukrainian/Russian Cossacks or Tatars), used mostly for reconnaissance.

Deployment

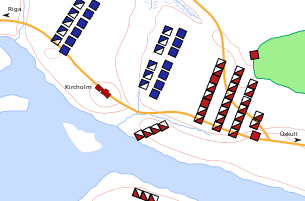

The Swedish forces seem to have been deployed in a checkerboard formation, made up of the infantry regiments formed into seven or eight well-spaced independent blocks, with intersecting fields of fire. The flanks were to be covered by the Swedish and German cavalry and the cannons were placed in front of the cavalry. Charles' force was formed into four lines on the crest of a ride, with the first line consisting of four infantry battalions, cavalry in the second line, six infantry battalions in the third line and cavalry in the fourth line.[1]:64 The infantry battalions formed in squares of thirty by thirty, with pikemen in the center and shot on the edges, and gaps between the squares allowed passage of their cavalry.[1]:64

Jan Karol Chodkiewicz deployed his forces in the traditional deep Polish–Lithuanian battle formation – the so-called "Old Polish Order" – with the left wing significantly stronger and commanded by Tomasz Dąbrowa, while the right wing was composed of a smaller number of hussars under Jan Piotr Sapieha and the centre, which included Hetman Chodkiewicz's own company of 300 hussars led by lieutenant Wincenty Woyna and a powerful formation of reiters sent by the Duke of Courland Friedrich Kettler.[1]:66 The Lithuanian infantry supported by Poles, mostly armed in Hungarian haiduk-style, drew up in the centre. Some 280 hussars were left as a general reserve under Teodor Lacki.

Battle

Chodkiewicz tried for four hours to lure the Swedes from their positions with his light cavalry sent out to skirmish between the two armies.[1]:64 Chodkiewicz, having smaller forces (approximately a 1:3 disadvantage), used a feint to lure the Swedes off their high position, pretending to withdraw.[1]:64 The Swedes under Charles thought that the Lithuanians and supporting Poles were retreating and therefore advanced to the bottom of the slope, using his second line of cavalry to cover his flanks while the first line of infantry closed up.[1]:65 This is what Chodkiewicz was waiting for. The Commonwealth forces now gave fire with Kettlers' Courland harquebusiers while Wincenty Wojna's hussars charged at the Swedish lines, causing disorder in the infantry.[1]:65

The main battle started with the Polish–Lithuanian cavalry charge on the Swedish right flank, with about 1,000 hussars shattering Mansfield's reiters, and disordering the Swedish third line of infantry in their retreat.[1]:65 At the same time, on the Swedish left, 650 hussars under Jan Piotr Sapieha charged.[1]:65 After Charles sent in his reserve of 700 cavalry, Chodkiewicz sent in his reserves. The entire force of Swedish cavalry was finally put to rout, and in their flight disordered many of their own infantry, leaving them vulnerable to the hussars' charge.[1]:65

Within 30 minutes, the Swedish cavalry was in full retreat on both flanks exposing the infantry in the center to the hussars and the firepower of Chodkiewicz's infantry.[1]:65 The Swedish defeat was utter and complete.[1]:65 The army of Charles IX had lost at least half, perhaps as much as two-thirds, of its original strength. The Polish–Lithuanian losses numbered only about 100 dead[1]:65 and 200 wounded, although the hussars, in particular, lost a large part of their trained battle horses.

As in all crushing victories in this period, the larger part of the Swedish losses were suffered during the retreat, made more difficult by the dense forests and marshes on the route back to Riga, many drowning crossing the Dvina.[1]:65 The Lithuanians and Poles spared few. Polish–Lithuanian casualties were light, in large part due to the speed of the victory. During the hussar's charges it was the horses that took the greatest damage, the riders being largely protected by the body and heads of their horses.

Aftermath

After the defeat, the Swedish king was forced to abandon the siege of Riga and withdraw by ship back across the Baltic Sea to Sweden and to relinquish control of northern Latvia and Estonia. However, the Commonwealth proved unable to exploit the victory fully because there was no money for the troops, who had not been paid for months. Without pay they could not buy food or fodder for their horses or replenish their military supplies, and so the campaign faltered. An additional factor was the large number of trained horses lost during the battle, which proved difficult to replace.

A truce was eventually signed in 1611, but by 1617 war broke out again, and finally in 1621 the new Swedish king, Gustavus Adolphus, landed near Riga and took the city with a brief siege, wiping away – in Swedish eyes – much of the shame suffered at Kircholm.

The Battle of Kircholm is commemorated on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Warsaw, with the inscription "KIRCHOLM 27 IX 1605".

References

- Frost, R.I., 2000, The Northern Wars, 1558–1721, Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4

- Bertil C:son Barkman, Kungl. Svea Livgardes Historia, bd. II: 1560–1611. Victor Pettersson (1939).

- Richard Brzezinski, Velimir Vukšić, "Polish Winged Hussar 1576–1775", Osprey Publishing, 2006, pg. 50

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Kirchholm. |

- Winged Hussars, Radoslaw Sikora, Bartosz Musialowicz, BUM Magazine, 2016.