Great Frost of 1709

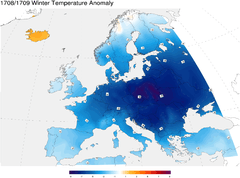

The Great Frost, as it was known in England, or Le Grand Hiver ("The Great Winter"), as it was known in France, was an extraordinarily cold winter in Europe in 1708–1709,[1] and was the coldest European winter during the past 500 years.[2] The severe cold occurred during the time of low sunspot activity known as the Maunder Minimum.

Notability

William Derham recorded in Upminster, near London, a low of −12 °C (10 °F) on the night of 5 January 1709, the lowest he had ever measured since he started taking readings in 1697. His contemporaries in the weather observation field in Europe likewise recorded lows down to −15 °C (5 °F). Derham wrote in Philosophical Transactions: "I believe the Frost was greater (if not more universal also) than any other within the Memory of Man."[3]

During the Great Northern War, the Swedish invasion of Russia led by Charles XII of Sweden against Russia's Peter the Great was notably weakened by the severe winter. Sudden winter storms and frosts killed thousands during the Swedish army's winter offensives, most noticeably during a single night away from camp that killed at least 2,000. Because the Russian troops were more prepared for the harmful weather and cautiously stayed within their camps, their losses were substantially lower, contributing heavily to their eventual victory at Poltava the following summer.[4]

France was particularly hard hit by the winter, with the subsequent famine estimated to have caused 600,000 deaths by the end of 1710.[5][6] Because the famine occurred during wartime, there were contemporary nationalist claims that there were no deaths from starvation in the kingdom of France in 1709.[7]

This winter event has drawn the attention of modern-day climatologists in the European Union's Millennium Project because they are presently unable to correlate the known causes of cold weather in Europe today with weather patterns documented in 1709. According to Dennis Wheeler, a climatologist at the University of Sunderland: "Something unusual seems to have been happening".[1]

The severity of the winter is thought to be an important factor in the emigration of the German Palatines from central Europe.

Anecdotal events

Elizabeth Charlotte, Madame Palatine, the Duchess of Orléans, had written a letter to her great aunt in Germany describing how she was still shivering from cold and could barely hold her pen despite having a roaring fire next to her, the door shut, and her entire person wrapped in furs. She wrote, "Never in my life have I seen a winter such as this one."[8]

European Union Millennium Project

One of the key aims of the European Union Millennium Project is climate reconstruction. This objective has gained significance in recent years because scientists are exploring the precise causes for climate variations instead of merely accepting they are within an acceptable historical range. Modern climate models do not appear to be entirely effective for explaining the climate of 1709.[9]

Song depictions

'The Coldest Winter in Memory' by Al Stewart on the album 'Seemed Like a Good Idea At The Time' describes the winter of 1709 from the perspective of a Swedish soldier in the Great Northern War.

References

- Pain, Stephanie (7 February 2009), "1709: The year that Europe froze", New Scientist.

- Luterbacher, Jürg; Dietrich, Daniel; Xoplaki, Elena; Grosjean, Martin; Wanner, Heinz (2004), "European Seasonal and Annual Temperature Variability, Trends, and Extremes Since 1500", Science, 303 (5663): 1499–1503, doi:10.1126/science.1093877, PMID 15001774

- Derham, W. (1708–1709), "The History of the Great Frost in the Last Winter 1703 and 1708/9", Philosophical Transactions, 26 (324): 454–478, doi:10.1098/rstl.1708.0073, JSTOR 103288.

- Massie, Robert, Peter the Great: His Life and World.

- Monahan, W. Gregory (1993), Year of Sorrows: The great famine of 1709 in Lyon, Columbus: Ohio State University Press, pp. 125–153, ISBN 978-0-8142-0608-9.

- Lachiver, Marcel (1991), Les Années De Misère: La famine au temps du Grand Roi, 1680–1720 (in French), Paris: Fayard, pp. 361, 381–382, ISBN 978-2-213-02799-9.

- Ó Gráda, Cormac & Chevet, Jean-Michel (2002), "Famine and Market in Ancien Régime France", Journal of Economic History, 62 (3): 706–733, doi:10.1017/S0022050702001055, hdl:10197/368, PMID 17494233.

- "Millennium European climate", Department of Geography, Masaryk University, January 26, 2009