Lithuanians

Lithuanians (Lithuanian: lietuviai, singular lietuvis/lietuvė) are a Baltic ethnic group, native to Lithuania, where they number around 2,561,300 people.[3] Another million or more make up the Lithuanian diaspora, largely found in countries such as the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Russia, United Kingdom and Ireland. Their native language is Lithuanian, one of only two surviving members of the Baltic language family. According to the census conducted in 2001, 83.45% of the population of Lithuania identified themselves as Lithuanians, 6.74% as Poles, 6.31% as Russians, 1.23% as Belarusians, and 2.27% as members of other ethnic groups. Most Lithuanians belong to the Roman Catholic Church, while the Lietuvininkai who lived in the northern part of East Prussia prior to World War II, were mostly Evangelical Lutherans.

Lietuviai | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

c. 3.7[1]–4.3 million[2]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 652,790 (2014)[lower-alpha 1][4] | |

| 212,000 (2018)[5] | |

| 200,000 (2002)[6][1] | |

| 85,617 (2011)[1] | |

| 49,130 (2011)[7] | |

| 45,415 (2019)[8][9] | |

| 39,000 (2014)[10] | |

| 36,683 (2011)[11] | |

| 24,426 (2011)[12] | |

| 20,000[lower-alpha 2][14] | |

| 15,596 (2019)[15] | |

| 12,714 (2017)[16] | |

| 12,317[17] | |

| 12,128[18] | |

| 10,000[19] | |

| 8,452 (2019)[20] | |

| 8,000 (2011)[21] | |

| 7,207 (2001)[22] | |

| 5,087 (2009)[23] | |

| 4,524[24] | |

| 4,000 | |

| 3,362 (2018)[25] | |

| 1,881 (2017)[26] | |

| 1,500[27] | |

| 600 | |

| 300[lower-alpha 3][28] | |

| 80 (2015)[28] | |

| Languages | |

| Lithuanian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic large Irreligious minority | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Balts | |

| |

History

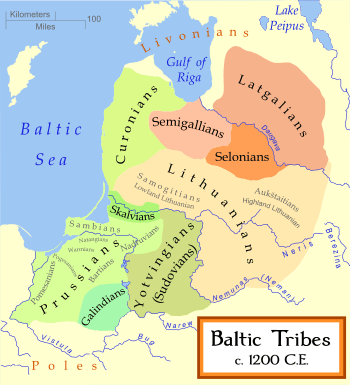

The territory of the Balts, including modern Lithuania, was once inhabited by several Baltic tribal entities (Aukštaitians, Sudovians, Old Lithuanians, Curonians, Semigallians, Selonians, Samogitians, Skalvians, Old Prussians (Nadruvians)), as attested by ancient sources and dating from prehistoric times. Over the centuries, and especially under the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, some of these tribes consolidated into the Lithuanian nation, mainly as a defence against the marauding Teutonic Order and Eastern Slavs. The last Pagan peoples in Europe, they were eventually converted to Christianity in 1387.

The territory inhabited by the ethnic Lithuanians has shrunk over centuries; once Lithuanians made up a majority of the population not only in what is now Lithuania, but also in northwestern Belarus, in large areas of the territory of the modern Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia, and in some parts of modern Latvia and Poland.[29]

However, there is a current argument that the Lithuanian language was considered non-prestigious enough by some elements in Lithuanian society, and a preference for the Polish language in certain territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, as well as a preference for the German language in territories of the former East Prussia (now Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia) caused the number of Lithuanian speakers to decrease. The subsequent imperial Russian occupation accelerated this process; it pursued a policy of Russification, which included a ban on public speaking and writing in Lithuanian (see, e.g., Knygnešiai, the actions against the Catholic Church). It was believed by some at the time that the nation as such, along with its language, would become extinct within a few generations.

At the end of the 19th century a Lithuanian cultural and linguistic revival occurred. Some of the Polish- and Belarusian-speaking persons from the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania expressed their affiliation with the modern Lithuanian nation in the early 20th century, including Michał Pius Römer, Stanisław Narutowicz, Oscar Milosz and Tadas Ivanauskas. Lithuania declared independence after World War I, which helped its national consolidation. A standardised Lithuanian language was approved. However, the eastern parts of Lithuania, including the Vilnius Region, were annexed by Poland, while the Klaipėda Region was taken over by Nazi Germany in 1939. In 1940, Lithuania was invaded and occupied by the Soviet Union, and forced to join it as the Lithuanian SSR. The Germans and their allies attacked the USSR in June 1941, and from 1941–1944, Lithuania was occupied by Germany. The Germans retreated in 1944, and Lithuania fell under Soviet rule once again. The long-standing communities of Lithuanians in the Kaliningrad Oblast (Lithuania Minor) were almost destroyed as a result.

The Lithuanian nation as such remained primarily in Lithuania, few villages in northeastern Poland, southern Latvia and also in the diaspora of emigrants. Some indigenous Lithuanians still remain in Belarus and the Kaliningrad Oblast, but their number is small compared to what they used to be. Lithuania regained its independence in 1990, and was recognized by most countries in 1991. It became a member of the European Union on May 1, 2004.

Ethnic composition of Lithuania

Among the Baltic states, Lithuania has the most homogeneous population. According to the census conducted in 2001, 83.45% of the population identified themselves as ethnic Lithuanians, 6.74% as Poles, 6.31% as Russians, 1.23% as Belarusians, and 2.27% as members of other ethnic groups such as Ukrainians, Jews, Germans, Tatars, Latvians, Romani, Estonians, Crimean Karaites, Scandinavians etc.

Poles are mostly concentrated in the Vilnius Region. Especially large Polish communities are located in the Vilnius District Municipality and the Šalčininkai District Municipality. This concentration allows Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania, an ethnic minority-based political party, to exert political influence. Due to the excessive pro-Pole political agenda, the party is known to cause friction between Lithuanians and Poles. However, it has only held 1 or 2 seats in the parliament of Lithuania for the past decade. Thus, it is more active in local politics by having a majority in a few minor municipality councils.

Russians, even though they are almost as numerous as Poles, are much more evenly scattered and do not have a strong political party. The most prominent community lives in the Visaginas Municipality (52%). Most of them are workers who moved from Russia to work at the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant. A number of ethnic Russians left Lithuania after the declaration of independence in 1990.

In the past, the ethnic composition of Lithuania has varied dramatically. The most prominent change was the extermination of the Jewish population during the Holocaust. Before World War II, about 7.5% of the population was Jewish; they were concentrated in cities and towns and had a significant influence on crafts and business. They were called Litvaks and had a strong culture. The population of Vilnius, which was sometimes nicknamed the northern Jerusalem, was about 30% Jewish. Almost all its Jews were killed during the Holocaust in Nazi-occupied Lithuania, some 75,000 alone between the years 1941 – 1942,[30] while others later immigrated to the United States and Israel. Now there are about 3,200 Jews living in Lithuania.[3]

Cultural subgroups

Apart from the various religious and ethnic groups currently residing in Lithuania, Lithuanians themselves retain and differentiate between their regional identities; there are 5 historic regional groups: Žemaičiai, Suvalkiečiai, Aukštaičiai, Dzūkai and Prūsai,[31] the last of which is virtually extinct. City dwellers are usually considered just Lithuanians, especially ones from large cities such as Vilnius or Kaunas. The four groups are delineated according to certain region-specific traditions, dialects, and historical divisions. There are some stereotypes used in jokes about these subgroups, for example, Sudovians are supposedly frugal while Samogitians are stubborn.

Genetics

Since the Neolithic period the native inhabitants of the Lithuanian territory have not been replaced by migrations from outside, so there is a high probability that the inhabitants of present-day Lithuania have preserved the genetic composition of their forebears relatively undisturbed by the major demographic movements,[32] although without being actually isolated from them.[33] The Lithuanian population appears to be relatively homogeneous, without apparent genetic differences among ethnic subgroups.[34]

A 2004 analysis of mtDNA in a Lithuanian population revealed that Lithuanians are close to both Indo-European and Uralic-speaking populations of Northern Europe. Y-chromosome SNP haplogroup analysis showed Lithuanians to be closest to fellow Balts (Latvians), Estonians, Belarusians and Finnish people. This is the result of Iron Age.[35] Autosomal SNP analysis situates Lithuanians most proximal to Latvians, followed by the westernmost East Slavs, furthermore, all Slavic peoples and Germans are situated more proximal to Lithuanians than Finns and northern Russians.[36]

Lithuanian Ashkenazi Jews also have interesting genetics, since they display a number of unique genetic characteristics; the utility of these variations has been the subject of debate.[37] One variation, which is implicated in familial hypercholesterolemia, has been dated to the 14th century, corresponding to the establishment of Ashkenazi settlements in response to the invitation extended by Vytautas the Great in 1388.[38]

At the end of the 19th century, the average height of males was 163.5 cm (5 ft 4 in) and the average height of females was 153.3 cm (5 ft 0 in). By the end of the 20th century, heights averaged 181.3 cm (5 ft 11 in) for males and 167.5 cm (5 ft 6 in) for females.[39]

Diaspora

Lithuanian settlement extends into adjacent countries that are now outside the modern Lithuanian state. A small Lithuanian community exists in the vicinity of Puńsk and Sejny in the Suwałki area of Poland, an area associated with the Lithuanian writer and cleric Antanas Baranauskas. Although most of the Lithuanian inhabitants in the region of Lithuania Minor that formed part of East Prussia were expelled when the area was annexed by the Soviet Union as the Kaliningrad Oblast, small groups of Lithuanians subsequently settled that area as it was repopulated with new Soviet citizens.

Apart from the traditional communities in Lithuania and its neighboring countries, Lithuanians have emigrated to other continents during the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries.

- Communities in the United States make up the largest part of this diaspora; as many as one million Americans can claim Lithuanian descent. Emigration to America began in the 19th century, with the generation calling itself the “grynoriai” (derived from “greenhorn” meaning new and inexperienced).[40] The migration flow was interrupted during the Soviet occupation, when travel and emigration were severely restricted. The largest concentrations of Lithuanian Americans are in the Great Lakes area and the Northeast. Nearly 20,000 Lithuanians have immigrated to the United States since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.[41]

- Lithuanian communities in Canada are among the largest in the world along with the United States (See Lithuanian Canadian).

- Lithuanian communities in Mexico and South America (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Uruguay) developed before World War II, beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Currently, there is no longer a flow of emigrants to these destinations, since economic conditions in those countries are not better than those in Lithuania (see Lithuanians in Brazil).

- Lithuanian communities were formed in South Africa during the late 19th and 20th century, the majority being Jewish.

- Lithuanian communities in other regions of the former Soviet Union were formed during the Soviet occupation; the numbers of Lithuanians in Siberia and Central Asia increased dramatically when a large portion of Lithuanians were involuntarily deported into these areas. After de-Stalinization, however, most of them returned. Later, some Lithuanians were relocated to work in other areas of the Soviet Union; some of them did not return to Lithuania, after it became independent.

- The Lithuanian communities in Northwestern Europe (the United Kingdom, Ireland, Sweden, Norway and Iceland) are very new and began to appear after the restoration of independence to Lithuania in 1990; this emigration intensified after Lithuania became part of the European Union in 2004. London and Glasgow (especially the Bellshill and Coatbridge areas of Greater Glasgow) have long had large Catholic and Jewish Lithuanian populations. The Republic of Ireland probably has the highest concentration of Lithuanians relative to its total population size in Western Europe; its estimated 45,000 Lithuanians (about half of whom are registered) form over 1% of Ireland's total population. In Norway there are 45,415 Lithuanians living in the country and it has in a short time become the second largest ethnic minority in the country, making up 0.85% of Norway's total population, and 4.81% of all foreign residents in Norway.[42] There are around 3,500 Lithuanians in Iceland, making around 1% of the total population.

- Lithuanian communities in Germany began to appear after World War II. In 1950 they founded the Lithuanian High School in Diepholz, which was a private school for children of Lithuanian refugees. For decades the Lithuanian High School was the only full-time high school outside the Eastern Bloc offering courses in Lithuanian history, language, and culture. In 1954, the Lithuanian Community acquired Rennhof Manor House with its twelve-acre park in the town of Lampertheim-Hüttenfeld. The school was relocated there and still exists today.

- Lithuanian communities in Australia exist as well; due to its great distance from Europe, however, emigration there was minuscule. There are Lithuanian communities in Melbourne, Geelong, Sydney, Adelaide, Brisbane, Hobart and Perth.

Culture and traditions

The Lithuanian national sport is usually considered to be basketball (krepšinis), which is popular among Lithuanians in Lithuania as well as in the diasporic communities. Basketball came to Lithuania through the Lithuanian-American community in the 1930s. Lithuanian basketball teams were bronze medal winners in the 1992, 1996, and 2000 Summer Olympics.

Joninės (also known as Rasos) is a traditional national holiday, celebrated on the summer solstice. It has pagan origins. Užgavėnės (Shrove Tuesday) takes place on the day before Ash Wednesday, and is meant to urge the retreat of winter. There are also national traditions for Christian holidays such as Easter and Christmas.

Cuisine

Lithuanian cuisine has much in common with other European cuisines and features the products suited to its cool and moist northern climate: barley, potatoes, rye, beets, greens, and mushrooms are locally grown, and dairy products are one of its specialties. Nevertheless, it has its own distinguishing features, which were formed by a variety of influences during the country's rich history.

Since shared similarities in history and heritage, Lithuanians, Jews and Poles have developed many similar dishes and beverages: dumplings ( koldūnai), doughnuts (spurgos), and crepes (lietiniai blynai). German traditions also influenced Lithuanian cuisine, introducing pork and potato dishes, such as potato pudding (kugelis) and potato sausages (vėdarai), as well as the baroque tree cake known as šakotis. Traditional dishes of Lithuanian Tatars and Lithuanian Karaites like Kibinai and čeburekai, that are similar to pasty, are popular in Lithuania.

For Lithuanian Americans both traditional Lithuanian dishes of virtinukai (cabbage and noodles) and balandėliai (rolled cabbage) are growing increasingly more popular.

There are also regional cuisine dishes, e.g. traditional kastinys in Žemaitija, Western Lithuania, Skilandis in Western and Central Lithuania, Kindziukas in Eastern and Southern Lithuania (Dzūkija).

Cepelinai, a stuffed potato creation, is the most popular national dish. It is popular among Lithuanians all over the world. Other national foods include dark rye bread, cold beet soup (šaltibarščiai), and kugelis (a baked potato pudding). Some of these foods are also common in neighboring countries. Lithuanian cuisine is generally unknown outside Lithuanian communities. Most Lithuanian restaurants outside Lithuania are located in cities with a heavy Lithuanian presence.

Lithuanians in the early 20th century were among the thinnest people in the developed countries of the world.[43] In Lithuanian cuisine there is some emphasis on attractive presentation of freshly prepared foods.

Lithuanian has been brewing Midus, a type of Lithuanian Mead for thousands of years.[44]

Locally brewed beer (alus), vodka (degtinė), and kvass (gira) are popular drinks in Lithuania. Lithuanian traditional beer of Northern Lithuania, Biržai, Pasvalys regions is well appreciated in Lithuania and abroad.[45] Starka is a part of the Lithuanian heritage, still produced in Lithuania.

Literature

When the ban against printing the Lithuanian language was lifted in 1904, various European literary movements such as Symbolism, impressionism, and expressionism each in turn influenced the work of Lithuanian writers. The first period of Lithuanian independence (1918–40) gave them the opportunity to examine themselves and their characters more deeply, as their primary concerns were no longer political. An outstanding figure of the early 20th century was Vincas Krėvė-Mickevičius, a novelist and dramatist. His many works include Dainavos šalies senų žmonių padavimai (Old Folks Tales of Dainava, 1912) and the historical dramas Šarūnas (1911), Skirgaila (1925), and Mindaugo mirtis (The Death of Mindaugas, 1935). Petras Vaičiūnas was another popular playwright, producing one play each year during the 1920s and 1930s. Vincas Mykolaitis-Putinas wrote lyric poetry, plays, and novels, including the novel Altorių šešėly (In the Shadows of the Altars, 3 vol., 1933), a remarkably powerful autobiographical novel.

Keturi vėjai movement started with publication of The Prophet of the Four Winds by talented poet Kazys Binkis (1893—1942). It was rebellion against traditional poetry. The theoretical basis of Keturi vėjai initially was futurism which arrived through Russia from the West and later cubism, dadaism, surrealism, unanimism, and German expressionism. The most influensive futurist for Lithuanian writers was Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky.[46]

Oskaras Milašius (1877–1939) is a paradoxical and interesting phenomenon in Lithuanian culture. He never lived in Lithuania but was born and spent his childhood in Cereja (near Mogilev, Belarus) and graduated from Lycée Janson de Sailly in Paris. His longing for his fatherland was more metaphysical. Having to choose between two conflicting countries — Lithuania and Poland — he preferred Lithuania which for him was an idea even more than a fatherland. In 1920 when France recognized the independence of Lithuania, he was appointed officially as Chargé d'Affaires for Lithuania. He published: 1928, a collection of 26 Lithuanian songs; 1930, Lithuanian Tales and Stories; 1933, Lithuanian Tales; 1937, The origin of the Lithuanian Nation.

Folk music

Lithuanian folk music is based around songs (dainos), which include romantic and wedding songs, as well as work songs and archaic war songs. These songs used to be performed either in groups or alone, and in parallel chords or unison. Duophonic songs are common in the renowned sutartinės tradition of Aukštaitija. Another style of Lithuanian folk music is called rateliai, a kind of round dance. Instrumentation includes kanklės, a kind of zither that accompanies sutartinės, rateliai, waltzes, quadrilles and polkas, and fiddles, (including a bass fiddle called the basetle) and a kind of whistle called the Lamzdeliai lumzdelis; recent importations, beginning in the late 19th century, including the concertina, accordion and bandoneon. Sutartinė can be accompanied by skudučiai, a form of panpipes played by a group of people, as well as wooden trumpets (ragai and dandytės). Kanklės is an extremely important folk instrument, which differs in the number of strings and performance techniques across the country. Other traditional instruments include švilpas whistle, drums and tabalas (a percussion instrument like a gong), sekminių ragelis (bagpipe) and the pūslinė, a musical bow made from a pig's bladder filled with dried peas.[47]

Organizations in exile

- Ateitis – a Catholic youth organization whose members are called ateitininkai, started in Lithuania in 1910: During the occupation of Lithuania by the Soviet Union between 1945 and 1990 no Catholic organizations were allowed in Lithuania. The organization, however, continued to function in exile outside Lithuania. After Lithuania regained its independence in 1990, Ateitis returned to Lithuania as an official youth organization.[48] Many of the branches outside Lithuania continue to function serving Lithuanian emigrees and descendants.[49]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to People of Lithuania. |

- Lithuania

- Little Lithuania

- Baltic states

- List of Lithuanians

- List of Lithuanian philosophers

- Lithuanian American

- Lithuanians in the United Kingdom

- Lithuanian Scots

- Lithuanians in Brazil

References

- "Lietuviai Pasaulyje" (PDF). Lietuvos statistikos departamentas. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- Lietuviai Lietuvoje ir užsienyje: kur ir kiek mūsų yra Archived 2015-07-29 at the Wayback Machine

- "M3010215: Population at the beginning of the year by ethnicity". Data of 2011 Population Census. Lietuvos statistikos departamentas. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Savickas, Edgaras (20 February 2019). "Blogiausias "Brexit" scenarijus atrodo neišvengiamas: viskas, ką reikia žinoti". DELFI (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- "Um atalho para a Europa". Epoca. Editora Globo S.A. 24 June 2002. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013.

- "Statistics Canada"

- Innvandrere og norskfødte med innvandrerforeldre, 1. januar 2013 (in Norwegian) SSB, retrieved 9 June 2013

- Immigration to Norway

- "Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland - GENESIS-Online: Links". Archived from the original on 2018-07-04. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- Number of foreign nationals living in Ireland up 30% in last five years | BreakingNews.ie

- On key provisional results of Population and Housing Census 2011 | Latvijas statistika

- Lietuviai tango ritmu

- "Lithuanians in Argentina (contribute to & edit this article)". Archived from the original on 2016-08-08. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- "Statistics Sweden:FOLK2: Population 1. January by sex, age, ancestry, country of origin and citizenship".

- "Statistics Denmark:FOLK2: Population 1. January by sex, age, ancestry, country of origin and citizenship".

- 2054.0 Australian Census Analytic Program: Australians' Ancestries (2001 (Corrigendum))

- "INE. Anuario Estadístico de España 2006" [Statistical Yearbook of Spain 2006] (PDF). Spanish Statistical Office (INE) (in Spanish). 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2008.

- "Valstybės pažinimo centras". Prezidentas susitiko su Kazachstano lietuvių bendruomene ir verslo atstovais (in Lithuanian).

- "Centraal Bureu voor de Statistiek (CBS): Bevolking; geslacht, leeftijd, generatie en migratieachtergrond, 1 januari Gewijzigd op: 27 september 2019". Statistics Netherlands (in Dutch). 2019.

- "Raport z wyników: Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011" [Report from the results: National Census of Population and Housing] (PDF). Central Statistical Office (Poland) (in Polish). 2012. p. 106. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2012.

- State statistics committee of Ukraine – National composition of population, 2001 census (Ukrainian)

- Общая численность населения, его состав по возрасту, полу, состоянию в браке, уровню образования, национальностям, языку и источникам средств к существованию, Статистический бюллетень 2009, p.22

- "Popolazione residente in Italia proveniente dalla Lituania al 1° gennaio 2011". ISTAT. 2011. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- "Population by country of citizenship, sex and age 1 January 1998-2018". Reykjavík, Iceland: Statistics Iceland. 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- "Population by ethnic nationality, 1 January, years". Statistics Estonia. 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- "Uzbekijos lietuviai". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Table 16: Total migrant stock at mid-year by origin and by major area, region, country or area of destination, 2015" (XLS). United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. December 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Glanville Price. Encyclopedia of the languages of Europe, 2000, pp.304–306

- Sönke Neitzel & Harald Welzer, Soldaten (Protokolle vom Kämpfen, Töten und Sterben), Frankfurt am Main 2011, pp. 118–120 (Hebrew edition translated from the German) ISBN 978-965-552-818-3

- Vyšniauskaitė, Angelė (2005). "LIETUVIŲ ETNINĖ KULTŪRA – AKCENTAS DAUGIALYPĖJE EUROPOS KULTŪROJE" (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 2008-01-25. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- Česnys G. Anthropological roots of the Lithuanians. Science, Arts and Lithuania 1991; 1: p. 4-10.

- Daiva Ambrasienė, Vaidutis Kučinskas Genetic variability of the Lithuanian human population according to Y chromosome microsatellite markers Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Analysis in the Lithuanian Population Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Arrival of Siberian Ancestry Connecting the Eastern Baltic to Uralic Speakers further East". Cell.com. 9 May 2019. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.026. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Kushniarevich, A; et al. (2015). "Genetic Heritage of the Balto-Slavic Speaking Populations: A Synthesis of Autosomal, Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal Data". PLoS ONE. 10 (9): e0135820. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135820. PMC 4558026. PMID 26332464.

- Genetic diseases among the Ashkenazi

- Durst, Ronen; Colombo, Roberto; Shpitzen, Shoshi; Ben Avi, Liat; Friedlander, Yechiel; Wexler, Roni; Raal, Frederick J.; Marais, David A.; Defesche, Joep C.; Mandelshtam, Michail Y.; Kotze, Maritha J.; Leitersdorf, Eran; Meiner, Vardiella (2001). "Recent Origin and Spread of a Common Lithuanian Mutation, G197del LDLR, Causing Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Positive Selection Is Not Always Necessary to Account for Disease Incidence among Ashkenazi Jews". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (5): 1172–88. doi:10.1086/320123. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1226098. PMID 11309683.

- J. Tutkuviene. Sex and gender differences in secular trend of body size and frame indices of Lithuanians. Anthropologischer Anzeiger; Bericht über die biologisch-anthropologische Literatur. 2005 Mar;63(1):29–44.

- Milerytė-Japertienė, Giedrė (2019-04-16). "Grynoriai: Lithuanian-American life in the early 20th century". Europeana (CC By-SA). Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Immigration Statistics | Homeland Security

- "Innvandrere etter landbakgrunn. Antall og andel. 2019. Valgt region". www.kommuneprofilen.no (in Norwegian). Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Lissau, I.; et al. (January 2004). "Body mass index and overweight in adolescents in 13 European countries, Israel, and the United States". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 158 (1): 27–33. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.1.27. PMID 14706954.

- Antanas Astrauskas (2008), „Per barzdą varvėjo...“: svaigiųjų gėrimų istorija Lietuvoje ISBN 978-9955-23-141-7

- The NY Times picks beer trail in Lithuania among 46 places to visit in 2013

- "Alfonsas Nyka-Niliūnas. Keturi vėjai ir keturvėjinikai, Aidai, 1949, No. 24". Archived from the original on 2006-05-16. Retrieved 2006-06-23.

- Cronshaw, Andrew (2000). «Singing Revolutions», Broughton, Simon and Ellingham, Mark with McConnachie, James and Duane, Orla (Ed.) World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East, 16–24, London: Rough Guides. ISBN 1-85828-636-0.

- Homepage of Ateitis: Mission and Vision

- "Ateitis Foundation". Ateitininkų Namai. Lemont, IL. 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Lithuanians and Letts. |