Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) is a multilateral treaty that bans all nuclear tests, for both civilian and military purposes, in all environments. It was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 September 1996, but has not entered into force, as eight specific nations have not ratified the treaty.

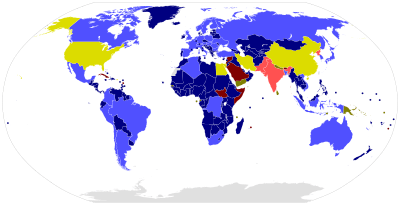

Participation in the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

| |||

| Signed | 10 September 1996 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | New York City | ||

| Effective | Not in force | ||

| Condition | 180 days after ratification by all 44 Annex 2 countries

| ||

| Signatories | 184 | ||

| Ratifiers | 168 (states that need to take further action for the treaty to enter into force: China, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, United States) | ||

| Depositary | Secretary-General of the United Nations | ||

| Languages | Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish | ||

| http://www.ctbto.org | |||

History

The movement for international control of nuclear weapons began in 1945, with a call from Canada and the United Kingdom for a conference on the subject.[1] In June 1946, Bernard Baruch, an emissary of President Harry S. Truman, proposed the Baruch Plan before the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission, which called for an international system of controls on the production of atomic energy. The plan, which would serve as the basis for United States nuclear policy into the 1950s, was rejected by the Soviet Union as a US ploy to cement its nuclear dominance.[2][3]

Between the Trinity nuclear test of 16 July 1945 and the signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) on 5 August 1963, 499 nuclear tests were conducted.[4] Much of the impetus for the PTBT, the precursor to the CTBT, was rising public concern surrounding the size and resulting nuclear fallout from underwater and atmospheric nuclear tests, particularly tests of powerful thermonuclear weapons (hydrogen bombs). The Castle Bravo test of 1 March 1954, in particular, attracted significant attention as the detonation resulted in fallout that spread over inhabited areas and sickened a group of Japanese fishermen.[5][6][7][8][9] Between 1945 and 1963, the US conducted 215 atmospheric tests, the Soviet Union conducted 219, the UK conducted 21, and France conducted three.[10]

In 1954, following the Castle Bravo test, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru of India issued the first appeal for a "standstill agreement" on testing, which was soon echoed by the British Labour Party.[11][12][13] Negotiations on a comprehensive test ban, primarily involved the US, UK, and the Soviet Union, began in 1955 following a proposal by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev.[14][15] Of primary concern throughout the negotiations, which would stretch with some interruptions to July 1963, was the system of verifying compliance with the test ban and detecting illicit tests. On the Western side, there were concerns that the Soviet Union would be able to circumvent any test ban and secretly leap ahead in the nuclear arms race.[16][17][18] These fears were amplified following the US Rainier shot of 19 September 1957, which was the first contained underground test of a nuclear weapon. Though the US held a significant advantage in underground testing capabilities, there was worry that the Soviet Union would be able to covertly conduct underground tests during a test ban, as underground detonations were more challenging to detect than above-ground tests.[19][20] On the Soviet side, conversely, the on-site compliance inspections demanded by the US and UK were seen as amounting to espionage.[21] Disagreement over verification would lead to the Anglo-American and Soviet negotiators abandoning a comprehensive test ban (i.e., a ban on all tests, including those underground) in favor of a partial ban, which would be finalized on 25 July 1963. The PTBT, joined by 123 states following the original three parties, banned detonations for military and civilian purposes underwater, in the atmosphere, and outer space.[22][23][24]

The PTBT had mixed results. On the one hand, enactment of the treaty was followed by a substantial drop in the atmospheric concentration of radioactive particles.[25][26] On the other hand, nuclear proliferation was not halted entirely (though it may have been slowed) and nuclear testing continued at a rapid clip. Compared to the 499 tests from 1945 to the signing of the PTBT, 436 tests were conducted over the ten years following the PTBT.[27][14] Furthermore, US and Soviet underground testing continued "venting" radioactive gas into the atmosphere.[28] Additionally, though underground testing was generally safer than above-ground testing, underground tests continued to risk the leaking of radionuclides, including plutonium, into the ground.[29][30][31] From 1964 through 1996, the year of the CTBT's adoption, an estimated 1,377 underground nuclear tests were conducted. The final non-underground (atmospheric or underwater) test was conducted by China in 1980.[32][33]

The PTBT has been seen as a step towards the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) of 1968, which directly referenced the PTBT.[34] Under the NPT, non-nuclear weapon states were prohibited from possessing, manufacturing, and acquiring nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices. All signatories, including nuclear weapon states, were committed to the goal of total nuclear disarmament. However, India, Pakistan, and Israel have declined to sign the NPT on the grounds that such a treaty is fundamentally discriminatory as it places limitations on states that do not have nuclear weapons while making no efforts to curb weapons development by declared nuclear weapons states.

In 1974, a step towards a comprehensive test ban was made with the Threshold Test Ban Treaty (TTBT), ratified by the US and Soviet Union, which banned underground tests with yields above 150 kilotons.[28][35] In April 1976, the two states reached agreement on the Peaceful Nuclear Explosions Treaty (PNET), which concerns nuclear detonations outside the weapons sites discussed in the TTBT. As in the TTBT, the US and Soviet Union agreed to bar peaceful nuclear explosions (PNEs) at these other locations with yields above 150 kilotons, as well as group explosions with total yields over 1,500 kilotons. To verify compliance, the PNET requires that states rely on national technical means of verification, share information on explosions, and grant on-site access to counterparties. The TTBT and PNET did not enter into force for the US and Soviet Union until 11 December 1990.[36]

In October 1977, the US, UK, and Soviet Union returned to negotiations over a test ban. These three nuclear powers made notable progress in the late 1970s, agreeing to terms on a ban on all testing, including a temporary prohibition on PNEs, but continued disagreements over the compliance mechanisms led to an end to negotiations ahead of Ronald Reagan's inauguration as President in 1981.[34] In 1985, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev announced a unilateral testing moratorium, and in December 1986, Reagan reaffirmed US commitment to pursue the long-term goal of a comprehensive test ban. In November 1987, negotiations on a test ban restarted, followed by a joint US-Soviet program to research underground-test detection in December 1987.[34][37]

Negotiations

Given the political situation prevailing in the subsequent decades, little progress was made in nuclear disarmament until the end of the Cold War in 1991. Parties to the PTBT held an amendment conference that year to discuss a proposal to convert the Treaty into an instrument banning all nuclear-weapon tests. With strong support from the UN General Assembly, negotiations for a comprehensive test-ban treaty began in 1993.

Adoption

Extensive efforts were made over the next three years to draft the Treaty text and its two annexes. However, the Conference on Disarmament, in which negotiations were being held, did not succeed in reaching consensus on the adoption of the text. Under the direction of Prime Minister John Howard and Foreign Minister Alexander Downer, Australia then sent the text to the United Nations General Assembly in New York, where it was submitted as a draft resolution.[38] On 10 September 1996, the Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) was adopted by a large majority, exceeding two-thirds of the General Assembly's Membership.[39]

Obligations

(Article I):[40]

- Each State Party undertakes not to carry out any nuclear weapon test explosion or any other nuclear explosion, and to prohibit and prevent any such nuclear explosion at any place under its jurisdiction or control.

- Each State Party undertakes, furthermore, to refrain from causing, encouraging, or in any way participating in the carrying out of any nuclear weapon test explosion or any other nuclear explosion.

Status

The Treaty was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 September 1996.[41] It opened for signature in New York on 24 September 1996,[41] when it was signed by 71 States, including five of the eight then nuclear-capable states. As of February 2019, 168 states have ratified the CTBT and another 17 states have signed but not ratified it.[42][43]

The treaty will enter into force 180 days after the 44 states listed in Annex 2 of the treaty have ratified it. These "Annex 2 states" are states that participated in the CTBT's negotiations between 1994 and 1996 and possessed nuclear power reactors or research reactors at that time.[44] As of 2016, eight Annex 2 states have not ratified the treaty: China, Egypt, Iran, Israel and the United States have signed but not ratified the Treaty; India, North Korea and Pakistan have not signed it.[45]

Monitoring

Geophysical and other technologies are used to monitor for compliance with the Treaty: forensic seismology, hydroacoustics, infrasound, and radionuclide monitoring.[46] The first three forms of monitoring are known as wave-form measurements. Seismic monitoring is performed with a system of 50 primary stations located throughout the world, with 120 auxiliary stations in signatory states.[47] Hydroacoustic monitoring is performed with a system of 11 stations that consist of hydrophone triads to monitor for underwater explosions. Hydroacoustic stations can of seismometers to measure T-waves from possible underwater explosions instead of hydrophones.[48] The best measurement of hydroacoustic waves has been found to be at a depth of 1000 m. Infrasound monitoring relies on changes in atmospheric pressure caused by a possible nuclear explosion, with 41 stations certified as of August 2019. One of the biggest concerns with infrasound measurements is noise due to exposure from wind, which can effect the sensor's ability to measure if an event occurred. Together, these technologies are used to monitor the ground, water, and atmosphere for any sign of a nuclear explosion.[49]

Radionuclide monitoring takes the form of either monitoring for radioactive particulates or noble gases as a product of a nuclear explosion.[50] Radioactive particles emit radiation that can be measured by any of the 80 stations located throughout the world. They are created from nuclear explosions that can collect onto the dust that is moved from the explosion.[51] If a nuclear explosion took place underground, noble gas monitoring can be used to verify whether or not a possible nuclear explosion took place. Noble gas monitoring relies on measuring increases in radioactive xenon gas. Different isotopes of xenon include 131mXe, 133Xe, 133mXe, and 135Xe. All four monitoring methods make up the International Monitoring System (IMS). Statistical theories and methods are integral to CTBT monitoring providing confidence in verification analysis. Once the Treaty enters into force, on-site inspections will be conducted where concerns about compliance arise.[52]

The Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), an international organization headquartered in Vienna, Austria, was created to build the verification framework, including establishment and provisional operation of the network of monitoring stations, the creation of an international data centre (IDC), and development of the on-site Inspection capability.[53] The CTBTO is responsible for collecting information from the IMS and distribute the analyzed and raw data to member states to judge whether or not a nuclear explosion occurred through the IDC. Parameters such as determining the location where a nuclear explosion or test took place is one of the things that the IDC can accomplish.[54] If a member state chooses to assert that another state had violated the CTBT, they can request an on-site inspection to take place to verify.[55]

The monitoring network consists of 337 facilities located all over the globe. As of May 2012, more than 260 facilities have been certified. The monitoring stations register data that is transmitted to the international data centre in Vienna for processing and analysis. The data are sent to states that have signed the Treaty.[56]

Subsequent nuclear testing

Three countries have tested nuclear weapons since the CTBT opened for signature in 1996. India and Pakistan both carried out two sets of tests in 1998. North Korea carried out six announced tests, one each in 2006, 2009, 2013, two in 2016 and one in 2017. All six North Korean tests were picked up by the International Monitoring System set up by the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization Preparatory Commission. A North Korean test is believed to have taken place in January 2016, evidenced by an "artificial earthquake" measured as a magnitude 5.1 by the U.S. Geological Survey. The first successful North Korean hydrogen bomb test supposedly took place in September 2017. It was estimated to have an explosive yield of 120 kilotons.[57][58][59][60]

See also

- List of weapons of mass destruction treaties

- Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization

- Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization Preparatory Commission

- National technical means of verification

- Nuclear disarmament

- Nuclear-free zone

- Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

References

- Polsby 1984, p. 56.

- Strode 1990, p. 7.

- Polsby 1984, pp. 57–58.

- Delcoigne, G.C. "The Test Ban Treaty" (PDF). IAEA. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Limited or Partial Test Ban Treaty (LTBT/PTBT)". Atomic Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- Burr, William; Montford, Hector L. (3 August 2003). "The Making of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, 1958–1963". National Security Archive. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- "Treaty Banning Nuclear Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water (Partial Test Ban Treaty) (PTBT)". Nuclear Threat Initiative. 26 October 2011. Archived from the original on 26 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- Rhodes 2005, p. 542.

- Strode 1990, p. 31.

- "Archive of Nuclear Data". Natural Resources Defense Council. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- Burns & Siracusa 2013, p. 247.

- Polsby 1984, p. 58.

- "1 March 1954 – Castle Bravo". Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- Rhodes 2008, p. 72.

- Reeves 1993, p. 121.

- Burns & Siracusa 2013, p. 305.

- Ambrose 1991, pp. 457–458.

- Seaborg 1981, pp. 8–9.

- Seaborg 1981, p. 9.

- Evangelista 1999, pp. 85–86.

- Evangelista 1999, p. 79.

- Schlesinger 2002, pp. 905–906, 910.

- "Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty & Partial Test Ban Treaty Membership" (PDF). Nuclear Threat Initiative. 8 June 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Radiocarbon Dating". Utrecht University. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- "The Technical Details: The Bomb Spike". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- Delcoigne, G.C. "The Test Ban Treaty" (PDF). IAEA. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Burr, William (2 August 2013). "The Limited Test Ban Treaty – 50 Years Later: New Documents Throw Light on Accord Banning Atmospheric Nuclear Testing". National Security Archive. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "General Overview of the Effects of Nuclear Testing". CTBTO Preparatory Commission. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Fallout from Nuclear Weapons". Report on the Health Consequences to the American Population from Nuclear Weapons Tests Conducted by the United States and Other Nations (Report). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 2005. pp. 20–21. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- Daryl Kimball and Wade Boese (June 2009). "Limited Test Ban Treaty Turns 40". Arms Control Association. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (2007). Armaments, Disarmament and International Security (PDF). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 555–556. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- "Nuclear testing world overview". Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization. 2012. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- "Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Chronology". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- "The Flawed Test Ban Treaty". The Heritage Foundation. 27 March 1984. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Peaceful Nuclear Explosions Treaty (PNET)". United States Department of State. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Blakeslee, Sandra (18 August 1988). "In Remotest Nevada, a Joint U.S. and Soviet Test". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Comprehensive nuclear-test-ban treaty: draft resolution". United Nations. 6 September 1996. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- "Resolution adopted by the general assembly:50/245. Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty". United Nations. 17 September 1996. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- "Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty CTBTO" (PDF). CTBTO Preparatory Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- United Nations Treaty Collection (2009). "Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Archived 3 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- "Status of Signature and Ratification". Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization. 2011. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- David E. Hoffman (1 November 2011), "Supercomputers offer tools for nuclear testing — and solving nuclear mysteries", The Washington Post; National, archived from the original on 3 April 2015, retrieved 30 November 2013

In this news article, the number of states ratifying was reported as 154. - "The Russian Federation's support for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty". CTBTO Preparatory Commission. 2008. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- "STATE DEPARTMENT TELEGRAM 012545 TO INTSUM COLLECTIVE, "INTSUM: INDIA: NUCLEAR TEST UNLIKELY"". Nuclear Proliferation International History Project. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- "CTBT: International Monitoring System". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Richards, Paul. "Seismology and CTBT Verification". ldeo.columbia.edu. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Lawrence, Martin. "A Global Network of Hydroacoustic Stations for Monitoring the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty". acoustics.org. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Tóth, Tibor (1 August 2019). "Building Up the Regime for Verifying the CTBT | Arms Control Association". armscontrol.org. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Hafemeister, David (1 August 2019). "The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty: Effectively Verifiable | Arms Control Association". armscontrol.org. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- "Radionuclide monitoring: CTBTO Preparatory Commission". ctbto.org. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Ringbom, Anders; Miley, Harry (25 July 2009). "Radionuclide Monitoring" (PDF): 23–28 – via CTBTO. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO Preparatory Commission) | Treaties & Regimes | NTI". nti.org. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- National Academy of Sciences. 2002. Technical Issues Related to the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10471.

- Nikitin, Mary (1 September 2016). "Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty: Background and Current Developments" (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

- "US nuclear security administrator dagostino visits the CTBTO". CTBTO Preparatory Commission. 15 September 2009. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- "Highlight 2007: The CTBT Verification Regime Put to the Test – The Event in the DPRK on 9 October 2006". Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization. 2012. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- "Press Release June 2009: Experts Sure About Nature of the DPRK Event". Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization. 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- McKirdy, Euan (6 January 2016). "North Korea announces it conducted nuclear test". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- "North Korea claims successful hydrogen bomb test". CNBC. 3 September 2017. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

Sources

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1991). Eisenhower: Soldier and President. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0671747589.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burns, Richard Dean; Siracusa, Joseph M. (2013). A Global History of the Nuclear Arms Race: Weapons, Strategy, and Politics – Volume 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1440800955.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evangelista, Matthew (1999). Unarmed Forces: The Transnational Movement to End the Cold War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801487842.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Polsby, Nelson W. (1984). Political Innovation in America: The Politics of Policy Initiation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300034288.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strode, Rebecca (1990). "Soviet Policy Toward a Nuclear Test Ban: 1958–1963". In Mandelbaum, Michael (ed.). The Other Side of the Table: The Soviet Approach to Arms Control. New York and London: Council on Foreign Relations Press. ISBN 978-0876090718.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reeves, Richard (1993). President Kennedy: Profile of Power. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. p. 5. ISBN 978-0671892890.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rhodes, Richard (2005). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0684824147.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rhodes, Richard (2008). Arsenals of Folly: The Making of the Nuclear Arms Race. New York, NY: Vintage. ISBN 978-0375713941.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier Jr. (2002). A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0618219278.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seaborg, Glenn T. (1981). Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Test Ban. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520049611.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. |

- Full text of the treaty

- CTBTO Preparatory Commission — official news and information

- The Test Ban Test: U.S. Rejection has Scuttled the CTBT

- US conducts subcritical nuclear test ABC News, 24 February 2006

- International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, 1991

- Daryl Kimball and Christine Kucia, Arms Control Association, 2002

- General John M. Shalikashvili, Special Advisor to the President and the Secretary of State for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty

- Christopher Paine, Senior Researcher with NRDC's Nuclear Program, 1999

- Obama or McCain Can Finish Journey to Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

- For the number of nuclear explosions conducted in various parts of the globe from 1954–1998 see — https://web.archive.org/web/20101218010654/http://www.blip.tv/file/1662914

- Introductory note by Thomas Graham, Jr., procedural history note and audiovisual material on the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

- Lecture by Masahiko Asada titled Nuclear Weapons and International Law in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

- Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty: Background and Current Developments Congressional Research Service

- The Woodrow Wilson Center's Nuclear Proliferation International History Project or NPIHP is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews and other empirical sources.