Arabs

An Arab (/ˈær.əb/;[56] singular Arabic: عَرَبِيٌّ, ISO 233: ‘arabī; Arabic pronunciation: [ˈʕarabi]), plural Arabic: عَرَبٌ, ISO 233: ‘arab; Arabic pronunciation: [ˈʕarab] (![]()

عَرَبٌ ('arab) (in Arabic) | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

c. 400 million[1][2] to 420+ million[3][4]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 430,000,000[5][6] | |

| Estimated 4–7 million with at least partial ancestry[7][8][lower-alpha 1] | |

| 3.3[10] to 5.5[11] million people of North African (Arab or Berber) descent[12] | |

| 5,000,000[17][18][19][20][21] | |

| 4,500,000 at least partial ancestry[22] | |

| 3,700,000[23] | |

| 1,700,000[24] | |

| 1,600,000[25] | |

| 1,500,000[26] | |

| 1,500,000[27] | |

| 1,500,000[28] | |

| 1,536,000 (est.)[29] | |

| 1,350,000[30][31] | |

| 1,155,390[32][33] | |

| 800,000[34][35][36] | |

| 750,925[37] | |

| 680,000[38] | |

| 500,000[39] | |

| 500,000[40] | |

| 250,000[41] | |

| 275,000[42][43] | |

| 800,000 | |

| 480,000–613,800[44] | |

| 425,000 | |

| 121,000 | |

| More than 100,000[45][46][47][48][49] | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Islam (Sunni · Shia · Sufi · Ibadi · Alawite) Sizable minority: Christianity (Greek Orthodox · Greek Catholic) Smaller minority: Other monotheistic religions (Druze · Judaism · Bahá'í Faith) Historically: Pre-Islamic Arabian polytheism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Afroasiatic-speaking peoples (Berber), especially Semitic peoples such as Assyrians, Jews, Amharas and Tigrayans[50][50][51][52][53][54][55] | |

a Arab ethnicity should not be confused with non-Arab ethnicities that are also native to the Arab world.[55] b Not all Arabs are Muslims and not all Muslims are Arabs. An Arab can follow any religion or irreligion. c Arab identity is defined independently of religious identity. | |

The first mention of Arabs appeared in the mid-9th century BCE as a tribal people in eastern and southern Syria, and the north of the Arabian Peninsula.[59] The Arabs appear to have been under the vassalage of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–612 BCE), as well as the succeeding Neo-Babylonian (626–539 BCE), Achaemenid (539–332 BCE), Seleucid, and Parthian empires.[60] The Nabataeans, an Arab people, formed their Kingdom near Petra in the 3rd century BC. Arab tribes, most notably the Ghassanids and Lakhmids, begin to appear in the southern Syrian Desert from the mid 3rd century CE onward, during the mid to later stages of the Roman and Sasanian empires.[61]

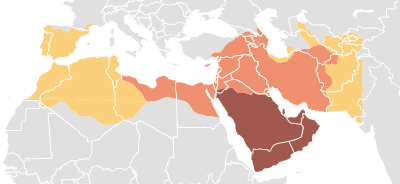

Before the expansion of the Rashidun Caliphate (632–661 C.E.), "Arab" referred to any of the largely nomadic and settled Semitic people from the Arabian Peninsula, Syrian Desert, and North and Lower Mesopotamia.[62] Today, "Arab" refers to a large number of people whose native regions form the Arab world due to the spread of Arabs and the Arabic language throughout the region during the early Muslim conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries and the subsequent Arabisation of indigenous populations.[63][64] The Arabs forged the Rashidun (632–661), Umayyad (661–750), Abbasid (750–1517) and the Fatimid (901–1071) caliphates, whose borders reached southern France in the west, China in the east, Anatolia in the north, and the Sudan in the south. This was one of the largest land empires in history.[65] In the early 20th century, the First World War signalled the end of the Ottoman Empire, which had ruled much of the Arab world since conquering the Mamluk Sultanate in 1517.[66] The end culminated in the 1922 defeat and dissolution of the empire and the partition of its territories, forming the modern Arab states.[67] Following the adoption of the Alexandria Protocol in 1944, the Arab League was founded on 22 March 1945.[68] The Charter of the Arab League endorsed the principle of an Arab homeland whilst respecting the individual sovereignty of its member states.[69]

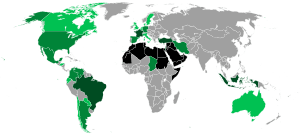

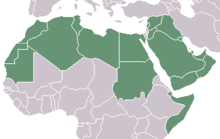

Today, Arabs primarily inhabit the 22 Arab states within the Arab League: Algeria, Bahrain, the Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. The Arab world stretches around 13 million km2, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast. Beyond the boundaries of the League of Arab States, Arabs can also be found in the global diaspora.[57] The ties that bind Arabs are ethnic, linguistic, cultural, historical, identical, nationalist, geographical and political.[70] The Arabs have their own customs, language, architecture, art, literature, music, dance, media, cuisine, dress, society, sports and mythology.[71]

Arabs are a diverse group in terms of religious affiliations and practices. In the pre-Islamic era, most Arabs followed polytheistic religions. Some tribes had adopted Christianity or Judaism, and a few individuals, the hanifs, apparently observed another form of monotheism.[72] Today, about 93% of Arabs are adherents of Islam,[73] and there are sizable Christian minorities.[74] Arab Muslims primarily belong to the Sunni, Shiite, Ibadi, and Alawite denominations. Arab Christians generally follow one of the Eastern Christian Churches, such as the Oriental Orthodox or Eastern Catholic churches.[75] There also exist small amounts of Arab Jews still living in Arab countries, and a much larger population of Jews descended from Arab Jewish communities living in Israel and various Western countries, who may or may not consider themselves Arab today. Many Christians in Arab countries may also not consider themselves Arab, especially Copts and Assyrians. Other smaller minority religions are also followed, such as the Bahá'í Faith and Druze.

Arabs have greatly influenced and contributed to diverse fields, notably the arts and architecture, language, philosophy, mythology, ethics, literature, politics, business, music, dance, cinema, medicine, science and technology in the ancient and modern history.[76]

Etymology

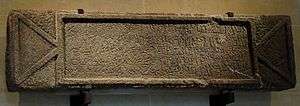

The earliest documented use of the word Arab in reference to a people appears in the Kurkh Monoliths, an Akkadian-language record of the Assyrian conquest of Aram (9th century BCE). The Monoliths used the term to refer to Bedouins of the Arabian Peninsula under King Gindibu, who fought as part of a coalition opposed to Assyria.[77] Listed among the booty captured by the army of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III in the Battle of Qarqar (853 BCE) are 1000 camels of "Gi-in-di-bu'u the ar-ba-a-a" or "[the man] Gindibu belonging to the Arabs" (ar-ba-a-a being an adjectival nisba of the noun ʿarab).[77]

The related word ʾaʿrāb is used to refer to Bedouins today, in contrast to ʿarab which refers to Arabs in general.[78] Both terms are mentioned around 40 times in pre-Islamic Sabaean inscriptions. The term ʿarab ('Arab') occurs also in the titles of the Himyarite kings from the time of 'Abu Karab Asad until MadiKarib Ya'fur. According to Sabaean grammar, the term ʾaʿrāb is derived from the term ʿarab. The term is also mentioned in Quranic verses, referring to people who were living in Madina and it might be a south Arabian loanword into Quranic language.[79]

The oldest surviving indication of an Arab national identity is an inscription made in an archaic form of Arabic in 328 CE using the Nabataean alphabet, which refers to Imru' al-Qays ibn 'Amr as 'King of all the Arabs'.[80][81] Herodotus refers to the Arabs in the Sinai, southern Palestine, and the frankincense region (Southern Arabia). Other Ancient-Greek historians like Agatharchides, Diodorus Siculus, and Strabo mention Arabs living in Mesopotamia (along the Euphrates), in Egypt (the Sinai and the Red Sea), southern Jordan (the Nabataeans), the Syrian steppe, and in eastern Arabia (the people of Gerrha). Inscriptions dating to the 6th century BCE in Yemen include the term 'Arab'.[82]

The most popular Arab account holds that the word Arab came from an eponymous father named Ya'rub, who was supposedly the first to speak Arabic. Abu Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdani had another view; he states that Arabs were called gharab ('westerners') by Mesopotamians because Bedouins originally resided to the west of Mesopotamia; the term was then corrupted into arab.

Yet another view is held by al-Masudi that the word Arab was initially applied to the Ishmaelites of the Arabah valley. In Biblical etymology, Arab (Hebrew: arvi) comes both from the desert origin of the Bedouins it originally described (arava means 'wilderness').

The root ʿ-r-b has several additional meanings in Semitic languages—including 'west, sunset', 'desert', 'mingle', 'mixed', 'merchant', and 'raven'—and are "comprehensible" with all of these having varying degrees of relevance to the emergence of the name. It is also possible that some forms were metathetical from ʿ-B-R, 'moving around' (Arabic: ʿ-B-R, 'traverse'), and hence, it is alleged, 'nomadic'.[83]

History

Antiquity

| Historical Arab states and dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ancient Arab States

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arab Empires

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eastern Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Western Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arabian Peninsula

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

East Africa

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Current monarchies

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pre-Islamic Arabia refers to the Arabian Peninsula prior to the rise of Islam in the 630s. The study of Pre-Islamic Arabia is important to Islamic studies as it provides the context for the development of Islam. Some of the settled communities in the Arabian Peninsula developed into distinctive civilizations. Sources for these civilizations are not extensive, and are limited to archaeological evidence, accounts written outside of Arabia, and Arab oral traditions later recorded by Islamic scholars. Among the most prominent civilizations was Dilmun, which arose around the 4th millennium BCE and lasted to 538 BCE, and Thamud, which arose around the 1st millennium BCE and lasted to about 300 CE. Additionally, from the beginning of the first millennium BCE, Southern Arabia was the home to a number of kingdoms, such as the Sabaean kingdom (Arabic: سَـبَـأ, romanized: Saba',[84] possibly Sheba),[85] and the coastal areas of Eastern Arabia were controlled by the Parthian and Sassanians from 300 BCE.

Origins and early history

According to Arab-Islamic-Jewish traditions, Ishmael was father of the Arabs, to be the ancestor of the Ishmaelites.[86]

The first written attestation of the ethnonym Arab occurs in an Assyrian inscription of 853 BCE, where Shalmaneser III lists a King Gindibu of mâtu arbâi (Arab land) as among the people he defeated at the Battle of Qarqar. Some of the names given in these texts are Aramaic, while others are the first attestations of Ancient North Arabian dialects. In fact several different ethnonyms are found in Assyrian texts that are conventionally translated "Arab": Arabi, Arubu, Aribi and Urbi. Many of the Qedarite queens were also described as queens of the aribi. The Hebrew Bible occasionally refers to Aravi peoples (or variants thereof), translated as "Arab" or "Arabian." The scope of the term at that early stage is unclear, but it seems to have referred to various desert-dwelling Semitic tribes in the Syrian Desert and Arabia. Arab tribes came into conflict with the Assyrians during the reign of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, and he records military victories against the powerful Qedar tribe among others.

Old Arabic diverges from Central Semitic by the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE.

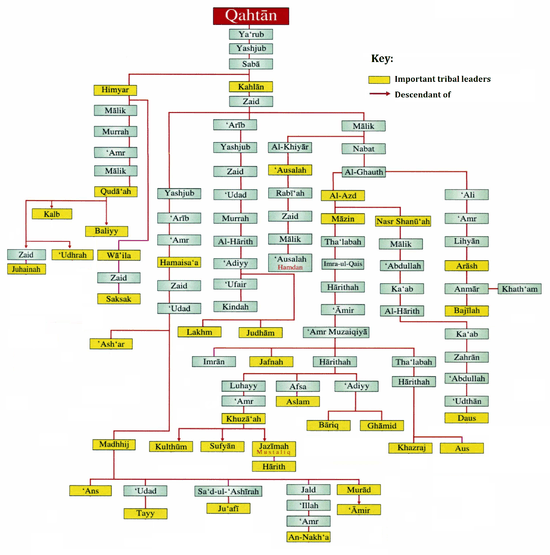

Medieval Arab genealogists divided Arabs into three groups:

- "Ancient Arabs", tribes that had vanished or been destroyed, such as ʿĀd and Thamud, often mentioned in the Qur'an as examples of God's power to vanquish those who fought his prophets.

- "Pure Arabs" of South Arabia, descending from Qahtan. The Qahtanites (Qahtanis) are said to have migrated from the land of Yemen following the destruction of the Ma'rib Dam (sadd Ma'rib).

- The "Arabized Arabs" (mustaʿribah) of Central Arabia (Najd) and North Arabia, descending from Ishmael the elder son of Abraham, through Adnan (hence, Adnanites). The Book of Genesis narrates that God promised Hagar to beget from Ishmael twelve princes and turn him to a great nation.(Genesis 17:20) The Book of Jubilees claims that the sons of Ishmael intermingled with the 6 sons of Keturah, from Abraham, and their descendants were called Arabs and Ishmaelites:

And Ishmael and his sons, and the sons of Keturah and their sons, went together and dwelt from Paran to the entering in of Babylon in all the land towards the East facing the desert. And these mingled with each other, and their name was called Arabs, and Ishmaelites.

— Book of Jubilees 20:13

_Central_Palace_Tiglath_pileser_III_728_BCE_British_Museum_AG.jpg)

Assyrian and Babylonian Royal Inscriptions and North Arabian inscriptions from 9th to 6th century BCE, mention the king of Qedar as king of the Arabs and King of the Ishmaelites.[88][89][90][91] Of the names of the sons of Ishmael the names "Nabat, Kedar, Abdeel, Dumah, Massa, and Teman" were mentioned in the Assyrian Royal Inscriptions as tribes of the Ishmaelites. Jesur was mentioned in Greek inscriptions in the 1st century BCE.[92]

Ibn Khaldun's Muqaddima distinguishes between sedentary Arab Muslims who used to be nomadic, and Bedouin nomadic Arabs of the desert. He used the term "formerly nomadic" Arabs and refers to sedentary Muslims by the region or city they lived in, as in Yemenis.[94] The Christians of Italy and the Crusaders preferred the term Saracens for all the Arabs and Muslims of that time.[95] The Christians of Iberia used the term Moor to describe all the Arabs and Muslims of that time.

Muslims of Medina referred to the nomadic tribes of the deserts as the A'raab, and considered themselves sedentary, but were aware of their close racial bonds. The term "A'raab" mirrors the term Assyrians used to describe the closely related nomads they defeated in Syria. The Qur'an does not use the word ʿarab, only the nisba adjective ʿarabiy. The Qur'an calls itself ʿarabiy, "Arabic", and Mubin, "clear". The two qualities are connected for example in ayat 43.2–3, "By the clear Book: We have made it an Arabic recitation in order that you may understand". The Qur'an became regarded as the prime example of the al-ʿarabiyya, the language of the Arabs. The term ʾiʿrāb has the same root and refers to a particularly clear and correct mode of speech. The plural noun ʾaʿrāb refers to the Bedouin tribes of the desert who resisted Muhammad, for example in at-Tawba 97,

al-ʾaʿrābu ʾašaddu kufrān wanifāqān "the Bedouin are the worst in disbelief and hypocrisy".

Based on this, in early Islamic terminology, ʿarabiy referred to the language, and ʾaʿrāb to the Arab Bedouins, carrying a negative connotation due to the Qur'anic verdict just cited. But after the Islamic conquest of the eighth century, the language of the nomadic Arabs became regarded as the most pure by the grammarians following Abi Ishaq, and the term kalam al-ʿArab, "language of the Arabs", denoted the uncontaminated language of the Bedouins.

Classical kingdoms

Proto-Arabic, or Ancient North Arabian, texts give a clearer picture of the Arabs' emergence. The earliest are written in variants of epigraphic south Arabian musnad script, including the 8th century BCE Hasaean inscriptions of eastern Saudi Arabia, the 6th century BCE Lihyanite texts of southeastern Saudi Arabia and the Thamudic texts found throughout the Arabian Peninsula and Sinai (not in reality connected with Thamud).

The Nabataeans were nomadic Arabs who moved into territory vacated by the Edomites – Semites who settled the region centuries before them. Their early inscriptions were in Aramaic, but gradually switched to Arabic, and since they had writing, it was they who made the first inscriptions in Arabic. The Nabataean alphabet was adopted by Arabs to the south, and evolved into modern Arabic script around the 4th century. This is attested by Safaitic inscriptions (beginning in the 1st century BCE) and the many Arabic personal names in Nabataean inscriptions. From about the 2nd century BCE, a few inscriptions from Qaryat al-Faw reveal a dialect no longer considered proto-Arabic, but pre-classical Arabic. Five Syriac inscriptions mentioning Arabs have been found at Sumatar Harabesi, one of which dates to the 2nd century CE.

Arabs arrived in the Palmyra in the late first millennium BCE.[96] The soldiers of the sheikh Zabdibel, who aided the Seleucids in the battle of Raphia (217 BCE), were described as Arabs; Zabdibel and his men were not actually identified as Palmyrenes in the texts, but the name "Zabdibel" is a Palmyrene name leading to the conclusion that the sheikh hailed from Palmyra.[97] Palmyra was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate after its 634 capture by the Arab general Khalid ibn al-Walid, who took the city on his way to Damascus; an 18-day march by his army through the Syrian Desert from Mesopotamia.[98] By then Palmyra was limited to the Diocletian camp.[99] After the conquest, the city became part of Homs Province.[100]

Palmyra prospered as part of the Umayyad Caliphate, and its population grew.[101] It was a key stop on the East-West trade route, with a large souq (Arabic: سُـوق, market), built by the Umayyads,[101][102] who also commissioned part of the Temple of Bel as a mosque.[102] During this period, Palmyra was a stronghold of the Banu Kalb tribe.[103] After being defeated by Marwan II during a civil war in the caliphate, Umayyad contender Sulayman ibn Hisham fled to the Banu Kalb in Palmyra, but eventually pledged allegiance to Marwan in 744; Palmyra continued to oppose Marwan until the surrender of the Banu Kalb leader al-Abrash al-Kalbi in 745.[104] That year, Marwan ordered the city's walls demolished.[99][105] In 750 a revolt, led by Majza'a ibn al-Kawthar and Umayyad pretender Abu Muhammad al-Sufyani, against the new Abbasid Caliphate swept across Syria;[106] the tribes in Palmyra supported the rebels.[107] After his defeat Abu Muhammad took refuge in the city, which withstood an Abbasid assault long enough to allow him to escape.[107]

Late kingdoms

The Ghassanids, Lakhmids and Kindites were the last major migration of pre-Islamic Arabs out of Yemen to the north. The Ghassanids increased the Semitic presence in the then Hellenized Syria, the majority of Semites were Aramaic peoples. They mainly settled in the Hauran region and spread to modern Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan.

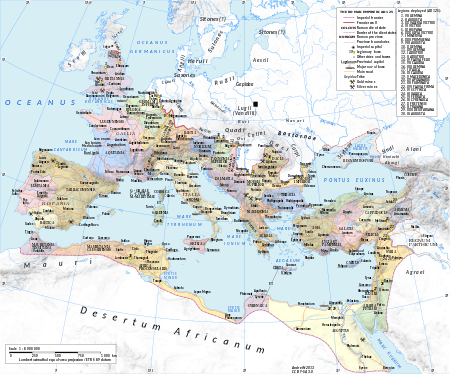

Greeks and Romans referred to all the nomadic population of the desert in the Near East as Arabi. The Romans called Yemen "Arabia Felix".[108] The Romans called the vassal nomadic states within the Roman Empire Arabia Petraea, after the city of Petra, and called unconquered deserts bordering the empire to the south and east Arabia Magna.

The Lakhmids as a dynasty inherited their power from the Tanukhids, the mid Tigris region around their capital Al-Hira. They ended up allying with the Sassanids against the Ghassanids and the Byzantine Empire. The Lakhmids contested control of the Central Arabian tribes with the Kindites with the Lakhmids eventually destroying Kinda in 540 after the fall of their main ally Himyar. The Persian Sassanids dissolved the Lakhmid dynasty in 602, being under puppet kings, then under their direct control.[109] The Kindites migrated from Yemen along with the Ghassanids and Lakhmids, but were turned back in Bahrain by the Abdul Qais Rabi'a tribe. They returned to Yemen and allied themselves with the Himyarites who installed them as a vassal kingdom that ruled Central Arabia from "Qaryah Dhat Kahl" (the present-day called Qaryat al-Faw). They ruled much of the Northern/Central Arabian peninsula, until they were destroyed by the Lakhmid king Al-Mundhir, and his son 'Amr.

Medieval period

Arab caliphates

Rashidun era (632–661)

After the death of Muhammad in 632, Rashidun armies launched campaigns of conquest, establishing the Caliphate, or Islamic Empire, one of the largest empires in history. It was larger and lasted longer than the previous Arab empire of Queen Mawia or the Aramean-Arab Palmyrene Empire. The Rashidun state was a completely new state and unlike the Arab kingdoms of its century such as the Himyarite, Lakhmids or Ghassanids.

Umayyad era (661–750 & 756–1031)

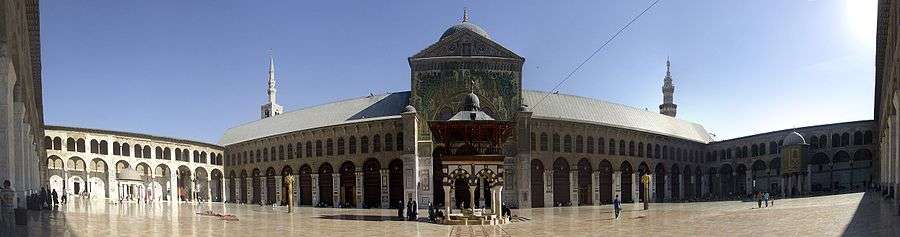

In 661, the Rashidun Caliphate fell into the hands of the Umayyad dynasty and Damascus was established as the empire's capital. The Umayyads were proud of their Arab identity and sponsored the poetry and culture of pre-Islamic Arabia. They established garrison towns at Ramla, Raqqa, Basra, Kufa, Mosul and Samarra, all of which developed into major cities.[111]

Caliph Abd al-Malik established Arabic as the Caliphate's official language in 686.[112] This reform greatly influenced the conquered non-Arab peoples and fueled the Arabization of the region. However, the Arabs' higher status among non-Arab Muslim converts and the latter's obligation to pay heavy taxes caused resentment. Caliph Umar II strove to resolve the conflict when he came to power in 717. He rectified the disparity, demanding that all Muslims be treated as equals, but his intended reforms did not take effect, as he died after only three years of rule. By now, discontent with the Umayyads swept the region and an uprising occurred in which the Abbasids came to power and moved the capital to Baghdad.

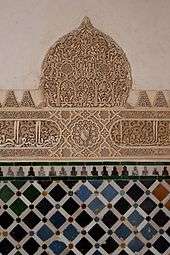

Umayyads expanded their Empire westwards capturing North Africa from the Byzantines. Before the Arab conquest, North Africa was conquered or settled by various people including Punics, Vandals and Romans. After the Abbasid Revolution, the Umayyads lost most of their territories with the exception of Iberia. Their last holding became known as the Emirate of Córdoba. It wasn't until the rule of the grandson of the founder of this new emirate that the state entered a new phase as the Caliphate of Córdoba. This new state was characterized by an expansion of trade, culture and knowledge, and saw the construction of masterpieces of al-Andalus architecture and the library of Al-Ḥakam II which housed over 400,000 volumes. With the collapse of the Umayyad state in 1031 CE, Islamic Spain was divided into small kingdoms.

Abbassid era (750–1258 & 1261–1517)

The Abbasids were the descendants of Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, one of the youngest uncles of Muhammad and of the same Banu Hashim clan. The Abbasids led a revolt against the Umayyads and defeated them in the Battle of the Zab effectively ending their rule in all parts of the Empire with the exception of al-Andalus. In 762, the second Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur founded the city of Baghdad and declared it the capital of the Caliphate. Unlike the Umayyads, the Abbasids had the support of non-Arab subjects.[111]

The Islamic Golden Age was inaugurated by the middle of the 8th century by the ascension of the Abbasid Caliphate and the transfer of the capital from Damascus to the newly founded city of Baghdad. The Abbassids were influenced by the Qur'anic injunctions and hadith such as "The ink of the scholar is more holy than the blood of martyrs" stressing the value of knowledge. During this period the Muslim world became an intellectual centre for science, philosophy, medicine and education as the Abbasids championed the cause of knowledge and established the "House of Wisdom" (Arabic: بيت الحكمة) in Baghdad. Rival dynasties such as the Fatimids of Egypt and the Umayyads of al-Andalus were also major intellectual centres with cities such as Cairo and Córdoba rivaling Baghdad.[113]

The Abbasids ruled for 200 years before they lost their central control when Wilayas began to fracture in the 10th century; afterwards, in the 1190s, there was a revival of their power, which was ended by the Mongols, who conquered Baghdad in 1258 and killed the Caliph Al-Musta'sim. Members of the Abbasid royal family escaped the massacre and resorted to Cairo, which had broken from the Abbasid rule two years earlier; the Mamluk generals taking the political side of the kingdom while Abbasid Caliphs were engaged in civil activities and continued patronizing science, arts and literature.

Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171)

The Fatimid caliphate was founded by al-Mahdi Billah, a descendant of Fatimah, the daughter of Muhammad, in the early 10th century. Egypt was the political, cultural, and religious centre of the Fatimid empire. The Fatimid state took shape among the Kutama Berbers, in the West of the North African littoral, in Algeria, in 909 conquering Raqqada, the Aghlabid capital. In 921 the Fatimids established the Tunisian city of Mahdia as their new capital. In 948 they shifted their capital to Al-Mansuriya, near Kairouan in Tunisia, and in 969 they conquered Egypt and established Cairo as the capital of their caliphate.

Intellectual life in Egypt during the Fatimid period achieved great progress and activity, due to many scholars who lived in or came to Egypt, as well as the number of books available. Fatimid Caliphs gave prominent positions to scholars in their courts, encouraged students, and established libraries in their palaces, so that scholars might expand their knowledge and reap benefits from the work of their predecessors.[114] The Fatimids were also known for their exquisite arts. Many traces of Fatimid architecture exist in Cairo today; the most defining examples include Al-Hakim Mosque and the Al-Azhar University.

It was not until the 11th century that the Maghreb saw a large influx of ethnic Arabs. Starting with the 11th century, the Arab bedouin Banu Hilal tribes migrated to the West. Having been sent by the Fatimids to punish the Berber Zirids for abandoning Shias, they travelled westwards. The Banu Hilal quickly defeated the Zirids and deeply weakened the neighboring Hammadids. According to some modern historians. their influx was a major factor in the arabization of the Maghreb.[115][116] Although Berbers ruled the region until the 16th century (under such powerful dynasties as the Almoravids, the Almohads, Hafsids, etc.), the arrival of these tribes eventually helped Arabize much of it ethnically, in addition to the linguistic and political impact on local non-Arabs.

Ottoman Empire

From 1517 to 1918, much of the Arab world was under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans defeated the Mamluk Sultanate in Cairo, and ended the Abbasid Caliphate. Arabs did not feel the change of administration because the Ottomans modeled their rule after the previous Arab administration systems.

In 1911, Arab intellectuals and politicians from throughout the Levant formed al-Fatat ("the Young Arab Society"), a small Arab nationalist club, in Paris. Its stated aim was "raising the level of the Arab nation to the level of modern nations." In the first few years of its existence, al-Fatat called for greater autonomy within a unified Ottoman state rather than Arab independence from the empire. Al-Fatat hosted the Arab Congress of 1913 in Paris, the purpose of which was to discuss desired reforms with other dissenting individuals from the Arab world. However, as the Ottoman authorities cracked down on the organization's activities and members, al-Fatat went underground and demanded the complete independence and unity of the Arab provinces.[117]

After World War I, when the Ottoman Empire was overthrown by the British Empire, former Ottoman colonies were divided up between the British and French as League of Nations mandates.

Modern period

Arabs in modern times live in the Arab world, which comprises 22 countries in Western Asia, North Africa, and parts of the Horn of Africa. They are all modern states and became significant as distinct political entities after the fall and defeat and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922).

Identity

Arab identity is defined independently of religious identity, and pre-dates the spread of Islam, with historically attested Arab Christian kingdoms and Arab Jewish tribes. Today, however, most Arabs are Muslim, with a minority adhering to other faiths, largely Christianity, but also Druze and Baha'i.[118][119]

Paternal descent has traditionally been considered the main source of affiliation in the Arab world when it comes to membership into an ethnic group or clan.[120]

Today, the main unifying characteristic among Arabs is Arabic, a Central Semitic language from the Afroasiatic language family. Modern Standard Arabic serves as the standardized and literary variety of Arabic used in writing. The Arabs are first mentioned in the mid-ninth century BCE as a tribal people dwelling in the central Arabian Peninsula subjugated by Upper Mesopotamia-based state of Assyria. The Arabs appear to have remained largely under the vassalage of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BCE), and then the succeeding Neo-Babylonian Empire (605–539 BCE), Persian Achaemenid Empire (539–332 BCE), Greek Macedonian/Seleucid Empire and Parthian Empire.

Arab tribes, most notably the Ghassanids and Lakhmids begin to appear in the south Syrian deserts and southern Jordan from the mid 3rd century CE onwards, during the mid to later stages of the Roman Empire and Sasanian Empire. Also, before them the Nabataeans of Jordan and arguably the Emessans,[121] Edessans,[122] and Hatrans[123] all appear to have been an Aramaic speaking ethnic Arabs who came to rule much of the pre-Islamic fertile crescent often as vassals of the two rival empires, the Sasanian (Persian) and the Byzantine (Eastern Roman).[124] Thus, although a more limited diffusion of Arab culture and language was felt in some areas by these migrant minority Arabs in pre-Islamic times through Arabic-speaking Christian kingdoms and Jewish tribes, it was only after the rise of Islam in the mid-7th century that Arab culture, people and language began their wholesale spread from the central Arabian Peninsula (including the south Syrian desert) through conquest and trade.

Subgroups

Arabs in the narrow sense are the indigenous Arabians who trace their roots back to the tribes of Arabia and their immediate descendant groups in the Levant and North Africa. Within the people of the Arabian Peninsula, distinction is made between:

- "Perishing Arabs" (Arabic: الـعـرب الـبـائـدة), which are ancient tribes about whose history little is known. They include ʿĀd (Arabic: عَـاد),[125] Thamûd (Arabic: ثَـمُـود),[126] Tasm, Jadis, Imlaq and others. Jadis and Tasm perished because of genocide. 'Aad and Thamud perished because of their decadence, as recorded in the Qur'an. Archaeologists have recently uncovered inscriptions that contain references to Iram dhāṫ al-'Imād (Arabic: إِرَم ذَات الـعِـمَـاد, Iram of the Pillars),[125] which was a major city of the 'Aad. Imlaq is the singular form of 'Amaleeq and is probably synonymous to the biblical Amalek.

- "Pure Arabs" (Arabic: الـعـرب الـعـاربـة) or Qahtanites from Yemen, taken to be descended from Ya'rub ibn Yashjub ibn Qahtan and further from Hud.

- "Arabized Arabs" (Arabic: الـعـرب الـمـسـتـعـربـة) or Adnanites, taken to be the descendants of Ishmael son of Abraham.

Arabians are most prevalent in the Arabian Peninsula, but are also found in large numbers in Mesopotamia (Arab tribes in Iraq), the Levant and Sinai (Negev Bedouin, Tarabin bedouin), as well as the Maghreb (Eastern Libya, South Tunisia and South Algeria) and the Sudan region.

This traditional division of the Arabs of Arabia may have arisen at the time of the First Fitna. Of the Arabian tribes that interacted with Muhammad, the most prominent was the Quraysh. The Quraysh subclan, the Banu Hashim, was the clan of Muhammad. During the early Muslim conquests and the Islamic Golden Age, the political rulers of Islam were exclusively members of the Quraysh.

The Arab presence in Iran did not begin with the Arab conquest of Persia in 633 CE. For centuries, Iranian rulers had maintained contacts with Arabs outside their borders, dealt with Arab subjects and client states (such as those of Iraq and Yemen), and settled Arab tribesmen in various parts of the Iranian plateau. It follows that the "Arab" conquests and settlements were by no means the exclusive work of Arabs from the Hejaz and the tribesmen of inner Arabia. The Arab infiltration into Iran began before the Muslim conquests and continued as a result of the joint exertions of the civilized Arabs (ahl al-madar) as well as the desert Arabs (ahl al-wabar).[127] The largest group of Iranian Arabs are the Ahwazi Arabs, including Banu Ka'b, Bani Turuf and the Musha'sha'iyyah sect. Smaller groups are the Khamseh nomads in Fars Province and the Arabs in Khorasan.

The Arabs of the Levant are traditionally divided into Qays and Yaman tribes. This tribal division is likewise taken to date to the Umayyad period. The Yemen trace their origin to South Arabia or Yemen; they include Banu Kalb, Kindah, Ghassanids, and Lakhmids.[128] Since the 1834 Peasants' revolt in Palestine, the Arabic-speaking population of Palestine has shed its formerly tribal structure and emerged as the Palestinians.

Native Jordanians are either descended from Bedouins (of which, 6% live a nomadic lifestyle),[129] or from the many deeply rooted non bedouin communities across the country, most notably Al-Salt city west of Amman which was at the time of Emirate the largest urban settlement east of the Jordan River. Along with indigenous communities in Al Husn, Aqaba, Irbid, Al Karak, Madaba, Jerash, Ajloun, Fuheis and Pella.[130] In Jordan, there is no official census data for how many inhabitants have Palestinian roots but they are estimated to constitute half of the population,[131][132] which in 2008 amounted to about 3 million.[132] Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics put their number at 3.24 million in 2009.[133]

_-_TIMEA.jpg)

The Bedouins of western Egypt and eastern Libya are traditionally divided into Saʿada and Murabtin, the Saʿada having higher social status. This may derive from a historical feudal system in which the Murabtin were vassals to the Saʿada.

In Sudan, there are numerous Arabic-speaking tribes, including the Shaigya, Ja'alin and Shukria, who are ancestrally related to the Nubians. These groups are collectively known as Sudanese Arabs. In addition, there are other Afroasiatic-speaking populations, such as Copts and Beja.

The medieval Arab slave trade in the Sudan drove a wedge between the Arabic-speaking groups and the indigenous Nilotic populations. Slavery substantially persists today along these lines.[134] It has contributed to ethnic conflict in the region, such as the Sudanese conflict in South Kordofan and Blue Nile, Northern Mali conflict, or the Boko Haram insurgency.

The Arabs of the Maghreb are descendants of Arabian tribes of Banu Hilal, the Banu Sulaym and the Maqil native of Middle East[135] and of other tribes native to Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Iraq. Arabs and Arabic-speakers inhabit plains and cities. The Banu Hilal spent almost a century in Egypt before moving to Libya, Tunisia and Algeria, and another century later some moved to Morocco, it is logical to think that they are mixed with inhabitants of Egypt and with Libya.[136]

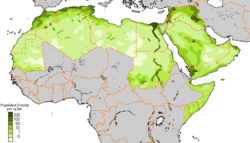

Demographics

The total number of Arabic speakers living in the Arab nations is estimated at 366 million by the CIA Factbook (as of 2014). The estimated number of Arabs in countries outside the Arab League is estimated at 17.5 million, yielding a total of close to 384 million.

Arab world

According to the Charter of the Arab League (also known as the Pact of the League of Arab States), the League of Arab States is composed of independent Arab states that are signatories to the Charter.[137]

Although all Arab states have Arabic as an official language, there are many non-Arabic-speaking populations native to the Arab world. Among these are Berbers, Toubou, Nubians, Jews, Kurds, Armenians.[55] Additionally, many Arab countries in the Persian Gulf have sizable non-Arab immigrant populations (10–30%). Iraq, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and Oman have a Persian speaking minority. The same countries also have Hindi-Urdu speakers and Filipinos as sizable minority. Balochi speakers are a good size minority in Oman. Additionally, countries like Bahrain, UAE, Oman and Kuwait have significant non-Arab and non-Muslim minorities (10–20%) like Hindus and Christians from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and the Philippines.

The table below shows the distribution of populations in the Arab world, as well as the official language(s) within the various Arab states.[138]

| Arab state | Population | Official language(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 38,700,000[139] | Arabic co-official language with Berber | |

| 1,314,089[140] | Arabic official language | |

| 780,971[141] | Arabic co-official language with Comorian and French | |

| 810,179[142] | Arabic co-official language with French | |

| 102,069,001[143] | Arabic official language | |

| 32,585,692[144] | Arabic co-official language with Kurdish | |

| 9,531,712[145] | Arabic official language | |

| 4,156,306[146] | Arabic official language | |

| 5,882,562[147] | Arabic official language | |

| 6,244,174[148] | Arabic official language | |

| 3,516,806[149] | Arabic official language | |

| 32,987,206[150] | Arabic co-official language with Berber | |

| 3,219,775[151] | Arabic official language | |

| 4,550,368[152] | Arabic official language | |

| 2,123,160[153] | Arabic official language | |

| 27,345,986[154] | Arabic official language | |

| 10,428,043[155] | Arabic co-official language with Somali | |

| 35,482,233[156] | Arabic co-official language with English | |

| 17,951,639[157] | Arabic official language | |

| 10,937,521[158] | Arabic official language | |

| 10,102,678[159] | Arabic official language | |

| 26,052,966[160] | Arabic official language |

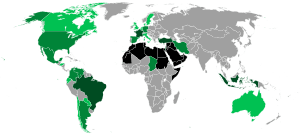

Arab diaspora

Arab diaspora refers to descendants of the Arab immigrants who, voluntarily or as refugees, emigrated from their native lands in non-Arab countries, primarily in East Africa, South America, Europe, North America, Australia and parts of South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, and West Africa. According to the International Organization for Migration, there are 13 million first-generation Arab migrants in the world, of which 5.8 million reside in Arab countries. Arab expatriates contribute to the circulation of financial and human capital in the region and thus significantly promote regional development. In 2009, Arab countries received a total of 35.1 billion USD in remittance in-flows and remittances sent to Jordan, Egypt and Lebanon from other Arab countries are 40 to 190 per cent higher than trade revenues between these and other Arab countries.[161] The 250,000 strong Lebanese community in West Africa is the largest non-African group in the region.[162][163] Arab traders have long operated in Southeast Asia and along the East Africa's Swahili coast. Zanzibar was once ruled by Omani Arabs.[164] Most of the prominent Indonesians, Malaysians, and Singaporeans of Arab descent are Hadhrami people with origins in southern Yemen in the Hadramawt coastal region.[165]

There are millions of Arabs living in Europe, mostly concentrated in France (about 6,000,000 in 2005[12]). Most Arabs in France are from the Maghreb but some also come from the Mashreq areas of the Arab world. Arabs in France form the second largest ethnic group after ethnically French people.[166] The modern Arab population of Spain numbers 1,800,000,[167][168][169][170] and there have been Arabs in Spain since the early 8th century when the Umayyad conquest of Hispania created the state of Al-Andalus.[171][172][173] In Germany the Arab population numbers over 1,000,000,[174] in Italy about 680,000,[38] in the United Kingdom between 366,769[175] and 500,000,[176] and in Greece between 250,000 and 750,000[177]). In addition, Greece is home to people from Arab countries who have the status of refugees (e.g. refugees of the Syrian civil war).[178] In the Netherlands 180,000,[179] and in Denmark 121,000. Other European countries are also home to Arab populations, including Norway, Austria, Bulgaria, Switzerland, North Macedonia, Romania and Serbia.[180] As of late 2015, Turkey had a total population of 78.7 million, with Syrian refugees accounting for 3.1% of that figure based on conservative estimates. Demographics indicated that the country previously had 1,500,000[181] to 2,000,000 Arab residents,[20] so Turkey's Arab population is now 4.5 to 5.1% of the total population, or approximately 4–5 million people.[20][19]

Arab immigration to the United States began in sizable numbers during the 1880s. Today, it is estimated that nearly 3.7 million Americans trace their roots to an Arab country.[23][182][183] Arab Americans are found in every state, but more than two thirds of them live in just ten states: California, Michigan, New York, Florida, Texas, New Jersey, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Metropolitan Los Angeles, Detroit, and New York City are home to one-third of the population.[23][184] Contrary to popular assumptions or stereotypes, the majority of Arab Americans are native-born, and nearly 82% of Arabs in the U.S. are citizens.[185][186][186][187][188] Arabs immigrants began to arrive in Canada in small numbers in 1882. Their immigration was relatively limited until 1945, after which time it increased progressively, particularly in the 1960s and thereafter.[189] According to the website "Who are Arab Canadians," Montreal, the Canadian city with the largest Arab population, has approximately 267,000 Arab inhabitants.[190]

Latin America has the largest Arab population outside of the Arab World.[191] Latin America is home to anywhere from 17–25 to 30 million people of Arab descent,[192] which is more than any other diaspora region in the world.[193][194] The Brazilian and Lebanese governments claim there are 7 million Brazilians of Lebanese descent.[195][196] Also, the Brazilian government claims there are 4 million Brazilians of Syrian descent.[195] According to research conducted by IBGE in 2008, covering only the states of Amazonas, Paraíba, São Paulo, Rio Grande do Sul, Mato Grosso and Distrito Federal, 0.9% of white Brazilian respondents said they had family origins in the Middle East.[197][198][199][200][201] Other large Arab communities includes Argentina (about 4,500,000[22][202][203]) The interethnic marriage in the Arab community, regardless of religious affiliation, is very high; most community members have only one parent who has Arab ethnicity.[204] Venezuela (over 1,600,000[25][205]), Colombia (over 1,600,000[26] to 3,200,000[206][207][208]), Mexico (over 1,100,000), Chile (over 800,000[209][210][211]), and Central America, particularly El Salvador, and Honduras (between 150,000 and 200,000).[43][35][36] is the fourth largest in the world after those in Israel, Lebanon, and Jordan. Arab Haitians (a large number of whom live in the capital) are more often than not, concentrated in financial areas where the majority of them establish businesses.[212][212][212]

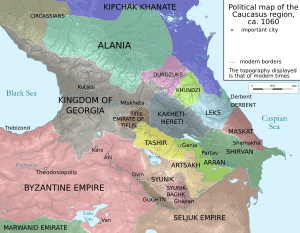

In 1728, a Russian officer described a group of Arab nomads who populated the Caspian shores of Mughan (in present-day Azerbaijan) and spoke a mixed Turkic-Arabic language.[213] It is believed that these groups migrated to the South Caucasus in the 16th century.[214] The 1888 edition of Encyclopædia Britannica also mentioned a certain number of Arabs populating the Baku Governorate of the Russian Empire.[215] They retained an Arabic dialect at least into the mid-19th century,[216] there are nearly 30 settlements still holding the name Arab (for example, Arabgadim, Arabojaghy, Arab-Yengija, etc.). From the time of the Arab conquest of the South Caucasus, continuous small-scale Arab migration from various parts of the Arab world occurred in Dagestan. The majority of these lived in the village of Darvag, to the north-west of Derbent. The latest of these accounts dates to the 1930s.[214] Most Arab communities in southern Dagestan underwent linguistic Turkicisation, thus nowadays Darvag is a majority-Azeri village.[217][218] According to the History of Ibn Khaldun, the Arabs that were once in Central Asia have been either killed or have fled the Tatar invasion of the region, leaving only the locals.[219] However, today many people in Central Asia identify as Arabs. Most Arabs of Central Asia are fully integrated into local populations, and sometimes call themselves the same as locals (for example, Tajiks, Uzbeks) but they use special titles to show their Arab origin such as Sayyid, Khoja or Siddiqui.[220]

There are only two communities in India which self-identify as Arabs, the Chaush of the Deccan region and the Chavuse of Gujarat.[221][222] These groups are largely descended from Hadhrami migrants who settled in these two regions in the 18th century. However, neither community still speaks Arabic, although the Chaush have seen re-immigration to the Arab States of the Persian Gulf and thus a re-adoption of Arabic.[223] In South Asia, where Arab ancestry is considered prestigious, many communities have origin myths that claim Arab ancestry. These include the Mappilla of Kerala and the Labbai of Tamil Nadu.[224] Among North Indian and Pakistani Arabs, there are groups who claim the status of Sayyid and have origin myths that allege descent from Muhammad.[225] The South Asian Iraqi biradri may be considered Arabs because records of their ancestors who migrated from Iraq exist in historical documents. There are about 5,000,000 Native Indonesians with Arab ancestry.[226] Arab Indonesians are mainly of Hadrami descent.[227][227] The Sri Lankan Moors are the third largest ethnic group in Sri Lanka, comprising 9.23% of the country's total population.[228] Some sources trace the ancestry of the Sri Lankan Moors to Arab traders who settled in Sri Lanka at some time between the 8th and 15th centuries.[229][230][231]

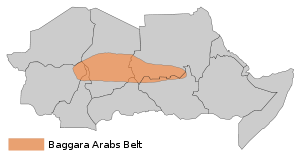

Afro-Arabs are individuals and groups from Africa who are of partial Arab descent. Most Afro-Arabs inhabit the Swahili Coast in the African Great Lakes region, although some can also be found in parts of the Arab world.[232][233] Large numbers of Arabs migrated to West Africa, particularly Côte d'Ivoire (home to over 100,000 Lebanese),[234] Senegal (roughly 30,000 Lebanese),[235] Sierra Leone (roughly 10,000 Lebanese today; about 30,000 prior to the outbreak of civil war in 1991), Liberia, and Nigeria.[236] Since the end of the civil war in 2002, Lebanese traders have become re-established in Sierra Leone.[237][238][239] The Arabs of Chad occupy northern Cameroon and Nigeria (where they are sometimes known as Shuwa), and extend as a belt across Chad and into Sudan, where they are called the Baggara grouping of Arab ethnic groups inhabiting the portion of Africa's Sahel. There are 171,000 in Cameroon, 150,000 in Niger[240]), and 107,000 in the Central African Republic.

Religion

Arabs are mostly Muslims with a Sunni majority and a Shia minority, one exception being the Ibadis, who predominate in Oman.[241] Arab Christians generally follow Eastern Churches such as the Greek Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches, though a minority of Protestant Church followers also exists.[242] There are also Arab communities consisting of Druze and Baha'is.[243][244]

Before the coming of Islam, most Arabs followed a pagan religion with a number of deities, including Hubal,[245] Wadd, Allāt,[246] Manat, and Uzza. A few individuals, the hanifs, had apparently rejected polytheism in favor of monotheism unaffiliated with any particular religion. Some tribes had converted to Christianity or Judaism. The most prominent Arab Christian kingdoms were the Ghassanid and Lakhmid kingdoms.[247] When the Himyarite king converted to Judaism in the late 4th century,[248] the elites of the other prominent Arab kingdom, the Kindites, being Himyirite vassals, apparently also converted (at least partly). With the expansion of Islam, polytheistic Arabs were rapidly Islamized, and polytheistic traditions gradually disappeared.[249][250]

Today, Sunni Islam dominates in most areas, overwhelmingly so in North Africa and the Horn of Africa. Shia Islam is dominant among the Arab population in Bahrain and southern Iraq while northern Iraq is mostly Sunni. Substantial Shia populations exist in Lebanon, Yemen, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia,[251] northern Syria and Al-Batinah Region in Oman. There are small numbers of Ibadi and non-denominational Muslims too.[241] The Druze community is concentrated in Lebanon, Syria, Israel and Jordan. Many Druze claim independence from other major religions in the area and consider their religion more of a philosophy. Their books of worship are called Kitab Al Hikma (Epistles of Wisdom). They believe in reincarnation and pray to five messengers from God. In Israel, the Druze have a status aparte from the general Arab population, treated as a separate ethno-religious community.

Christianity had a prominent presence In pre-Islamic Arabia among several Arab communities, including the Bahrani people of Eastern Arabia, the Christian community of Najran, in parts of Yemen, and among certain northern Arabian tribes such as the Ghassanids, Lakhmids, Taghlib, Banu Amela, Banu Judham, Tanukhids and Tayy. In the early Christian centuries, Arabia was sometimes known as Arabia heretica, due to its being "well known as a breeding-ground for heterodox interpretations of Christianity."[252] Christians make up 5.5% of the population of Western Asia and North Africa.[253] A sizeable share of those are Arab Christians proper, and affiliated Arabic-speaking populations of Copts and Maronites. In Lebanon, Christians number about 40.5% of the population.[147] In Syria, Christians make up 10% of the population.[157] In West Bank and in Gaza Strip, Christians make up 8% and 0.7% of the populations, respectively.[254][255] In Egypt, Coptic Christians number about 10% of the population. In Iraq, Christians constitute 0.1% of the population.[256] In Israel, Arab Christians constitute 2.1% (roughly 9% of the Arab population).[257] Arab Christians make up 8% of the population of Jordan.[258] Most North and South American Arabs are Christian,[259] so are about half of the Arabs in Australia who come particularly from Lebanon, Syria and Palestine. One well known member of this religious and ethnic community is Saint Abo, martyr and the patron saint of Tbilisi, Georgia.[260] Arab Christians also live in holy Christian cities such as Nazareth, Bethlehem and the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem and many other villages with holy Christian sites.

Culture

Arabic culture is the culture of Arab people, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea. Language, literature, gastronomy, art, architecture, music, spirituality, philosophy, mysticism (etc.) are all part of the cultural heritage of the Arabs.[261]

Arabs share basic beliefs and values that cross national and social class boundaries. Social attitudes have remained constant because Arab society is more conservative and demands conformity from its members.[262]

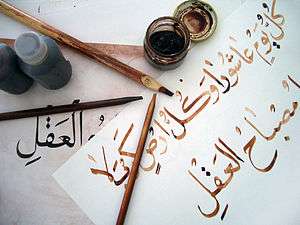

Language

Another important and unifying characteristic of Arabs is a common language. Arabic is a Semitic language of the Afro-Asiatic Family.[263] Evidence of its first use appears in accounts of wars in 853 BCE. It also became widely used in trade and commerce. Arabic also is a liturgical language of 1.7 billion Muslims.[264][265]

Arabic is one of six official languages of the United Nations.[266] It is revered as the language that God chose to reveal the Quran.[267][268]

Arabic has developed into at least two distinct forms. Classical Arabic is the form of the Arabic language used in literary texts from Umayyad and Abbasid times (7th to 9th centuries). It is based on the medieval dialects of Arab tribes. Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is the direct descendant used today throughout the Arab world in writing and in formal speaking, for example, prepared speeches, some radio broadcasts, and non-entertainment content,[269] while the lexis and stylistics of Modern Standard Arabic are different from Classical Arabic. Colloquial Arabic, an informal spoken language, varies by dialect from region to region; various forms of the language are in use today and provide an important force for Arab cohesion.[270]

Mythology

Arabic mythology comprises the ancient beliefs of the Arabs.[271] Prior to Islam the Kaaba of Mecca was covered in symbols representing the myriad demons, djinn, demigods, or simply tribal gods and other assorted deities which represented the polytheistic culture of pre-Islamic.[272][273] It has been inferred from this plurality an exceptionally broad context in which mythology could flourish. The most popular beasts and demons of Arabian mythology are Bahamut, Dandan, Falak, Ghoul, Hinn, Jinn, Karkadann, Marid, Nasnas, Qareen, Roc, Shadhavar, Werehyena and other assorted creatures which represented the profoundly polytheistic environment of pre-Islamic.[274]

The most obvious symbol of Arabian mythology is the Jinn or genie.[275] Jinns are supernatural beings of varying degrees of power. They possess free will (that is, they can choose to be good or evil) and come in two flavors. There are the Marids, usually described as the most powerful type of Jinn. These are the type of genie with the ability to grant wishes to humans. However, granting these wishes is not free. The Quran says that the jinn were created from "mārijin min nar" (smokeless fire or a mixture of fire; scholars explained, this is the part of the flame, which mixed with the blackness of fire).[276][277] They are not purely spiritual, but are also physical in nature, being able to interact in a tactile manner with people and objects and likewise be acted upon. The jinn, humans, and angels make up the known sapient creations of God.[278]

A ghoul is a monster or evil spirit in Arabic mythology, associated with graveyards and consuming human flesh,[279][280] demonic being believed to inhabit burial grounds and other deserted places. In ancient Arabic folklore, ghūls belonged to a diabolic class of jinn (spirits) and were said to be the offspring of Iblīs, the prince of darkness in Islam. They were capable of constantly changing form, but their presence was always recognizable by their unalterable sign—ass's hooves.[281] which describes the ghūl of Arabic folklore. The ghul is a devilish type of jinn believed to be sired by Iblis.[282]

Literature

Al-Jahiz (born 776, in Basra – December 868/January 869) was an Arab prose writer and author of works of literature, Mu'tazili theology, and politico-religious polemics. A leading scholar in the Abassid Caliphate, his canon includes two hundred books on various subjects, including Arabic grammar, zoology, poetry, lexicography, and rhetoric. Of his writings, only thirty books survive. Al-Jāḥiẓ was also one of the first Arabian writers to suggest a complete overhaul of the language's grammatical system, though this would not be undertaken until his fellow linguist Ibn Maḍāʾ took up the matter two hundred years later.[284]

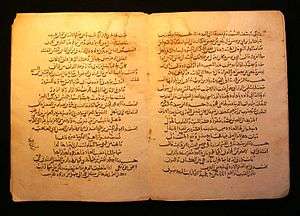

There is a small remnant of pre-Islamic poetry, but Arabic literature predominantly emerges in the Middle Ages, during the Golden Age of Islam.[285] Literary Arabic is derived from Classical Arabic, based on the language of the Quran as it was analyzed by Arabic grammarians beginning in the 8th century.[286]

A large portion of Arabic literature before the 20th century is in the form of poetry, and even prose from this period is either filled with snippets of poetry or is in the form of saj or rhymed prose.[288] The ghazal or love poem had a long history being at times tender and chaste and at other times rather explicit.[289] In the Sufi tradition the love poem would take on a wider, mystical and religious importance. Arabic epic literature was much less common than poetry, and presumably originates in oral tradition, written down from the 14th century or so. Maqama or rhymed prose is intermediate between poetry and prose, and also between fiction and non-fiction.[290] Maqama was an incredibly popular form of Arabic literature, being one of the few forms which continued to be written during the decline of Arabic in the 17th and 18th centuries.[291]

Arabic literature and culture declined significantly after the 13th century, to the benefit of Turkish and Persian. A modern revival took place beginning in the 19th century, alongside resistance against Ottoman rule. The literary revival is known as al-Nahda in Arabic, and was centered in Egypt and Lebanon. Two distinct trends can be found in the nahda period of revival.[292] The first was a neo-classical movement which sought to rediscover the literary traditions of the past, and was influenced by traditional literary genres—such as the maqama—and works like One Thousand and One Nights. In contrast, a modernist movement began by translating Western modernist works—primarily novels—into Arabic.[293] A tradition of modern Arabic poetry was established by writers such as Francis Marrash, Ahmad Shawqi and Hafiz Ibrahim. Iraqi poet Badr Shakir al-Sayyab is considered to be the originator of free verse in Arabic poetry.[294][295][296]

Gastronomy

Arabic cuisine is the cuisine of the Arab people.[297] The cuisines are often centuries old and reflect the culture of great trading in spices, herbs, and foods. The three main regions, also known as the Maghreb, the Mashriq, and the Khaleej have many similarities, but also many unique traditions. These kitchens have been influenced by the climate, cultivating possibilities, as well as trading possibilities. The kitchens of the Maghreb and Levant are relatively young kitchens which were developed over the past centuries. The kitchen from the Khaleej region is a very old kitchen. The kitchens can be divided into the urban and rural kitchens.

Arab cuisine mostly follows one of three culinary traditions – from the Maghreb, the Levant or the Persian Gulf states. In the Maghreb countries (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya) traditional main meals are tajines or dishes using couscous. In the Levant (Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria) main meals usually start with mezze – small dishes of dips and other items which are eaten with bread. This is typically followed by skewers of grilled lamb or chicken. Gulf cuisine, tends to be more highly spiced with more use of rice. Sometimes a lamb is roasted and served whole.[298]

One will find the following items in most dishes; cinnamon, fish (in coastal areas), garlic, lamb (or veal), mild to hot sauces, mint, onion, rice, saffron, sesame, yogurt, spices due to heavy trading between the two regions. Tea, thyme (or oregano), turmeric, a variety of fruits (primarily citrus) and vegetables such as cucumbers, eggplants, lettuce, tomato, green pepper, green beans, zucchini and parsley.[298][299]

Art

Arabic art takes on many forms, though it is jewelry, textiles and architecture that are the most well-known. It is generally split up by different eras, among them being early Arabic, early medieval, late medieval, late Arabic, and finally, current Arabic. One thing to remember is that many times a particular style from one era may continue into the next with few changes, while some have a drastic transformation. This may seem like a strange grouping of art mediums, but they are all closely related.[300][301]

Arabic writing is done from right to left, and was generally written in dark inks, with certain things embellished with special colored inks (red, green, gold). In early Arabic and early Medieval, writing was typically done on parchment made of animal skin. The ink showed up very well on it, and occasionally the parchment was dyed a separate color and brighter ink was used (this was only for special projects). The name given to the form of writing in early times was called Kufic script.[302]

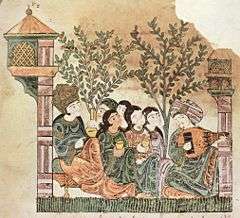

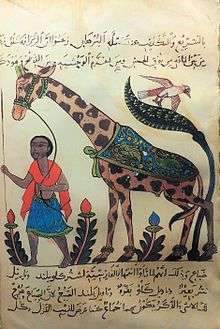

Arabic miniatures are small paintings on paper, whether book illustrations or separate works of art. Arabic miniature art dates to the late 7th century. Arabs depended on such art not only to satisfy their artistic taste, but also for scientific explanations.

Arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines,[303] often combined with other elements. Another definition is "Foliate ornament, typically using leaves, derived from stylised half-palmettes, which were combined with spiralling stems".[304] It usually consists of a single design which can be 'tiled' or seamlessly repeated as many times as desired.[305][306]

Architecture

Arabic Architecture has a deep diverse history, it dates to the dawn of the history in pre-Islamic Arabia and includes various styles from the Nabataean architecture to the old yet still used architecture in various regions of the Arab world. Each of it phases largely an extension of the earlier phase, it left also heavy impact on the architecture of other nations. Arab Architecture also encompasses a wide range of both secular and religious styles from the foundation of Islam to the present day. Some parts of its religious architectures raised by Muslim Arabs were influenced by cultures of Roman, Byzantine and cultures of other lands which the Arab conquered in the 7th and 8th centuries.[307][308]

In Sicily, Arab-Norman architecture combined Occidental features, such as the Classical pillars and friezes, with typical Arabic decorations and calligraphy. The principal Islamic architectural types are: the Mosque, the Tomb, the Palace and the Fort. From these four types, the vocabulary of Islamic architecture is derived and used for other buildings such as public baths, fountains and domestic architecture.[309][310]

Music

Arabic music, while independent and flourishing in the 2010s, has a long history of interaction with many other regional musical styles and genres. It is an amalgam of the music of the Arab people in the Arabian Peninsula and the music of all the peoples that make up the Arab world today.[311] Pre-Islamic Arab music was similar to that of Ancient Middle Eastern music. Most historians agree that there existed distinct forms of music in the Arabian peninsula in the pre-Islamic period between the 5th and 7th century CE. Arab poets of that "Jahili poets", meaning "the poets of the period of ignorance"—used to recite poems with a high notes.[312] It was believed that Jinns revealed poems to poets and music to musicians.[312][312] By the 11th century, Islamic Iberia had become a center for the manufacture of instruments. These goods spread gradually throughout France, influencing French troubadours, and eventually reaching the rest of Europe. The English words lute, rebec, and naker are derived from Arabic oud, rabab, and naqareh.[313][314]

A number of musical instruments used in classical music are believed to have been derived from Arabic musical instruments: the lute was derived from the Oud, the rebec (ancestor of violin) from the rebab, the guitar from qitara, which in turn was derived from the Persian Tar, naker from naqareh, adufe from al-duff, alboka from al-buq, anafil from al-nafir, exabeba from al-shabbaba (flute), atabal (bass drum) from al-tabl, atambal from al-tinbal,[315] the balaban, the castanet from kasatan, sonajas de azófar from sunuj al-sufr, the conical bore wind instruments,[316] the xelami from the sulami or fistula (flute or musical pipe),[317] the shawm and dulzaina from the reed instruments zamr and al-zurna,[318] the gaita from the ghaita, rackett from iraqya or iraqiyya,[319] geige (violin) from ghichak,[320] and the theorbo from the tarab.[321]

During the 1950s and the 1960s, Arabic music began to take on a more Western tone – artists Umm Kulthum, Abdel Halim Hafez, and Shadia along with composers Mohamed Abd al-Wahab and Baligh Hamdi pioneered the use of western instruments in Egyptian music. By the 1970s several other singers had followed suit and a strand of Arabic pop was born. Arabic pop usually consists of Western styled songs with Arabic instruments and lyrics. Melodies are often a mix between Eastern and Western. Beginning in the mid-1980s, Lydia Canaan, musical pioneer widely regarded as the first rock star of the Middle East[322][323][324][325][326][327][328][329]

Spirituality

Arab polytheism was the dominant religion in pre-Islamic Arabia. Gods and goddesses, including Hubal and the goddesses al-Lāt, Al-'Uzzá and Manāt, were worshipped at local shrines, such as the Kaaba in Mecca, whilst Arabs in the south, in what is today's Yemen, worshipped various gods, some of which represented the Sun or Moon. Different theories have been proposed regarding the role of Allah in Meccan religion.[72][330][331][332] Many of the physical descriptions of the pre-Islamic gods are traced to idols, especially near the Kaaba, which is said to have contained up to 360 of them.[333] Until about the fourth century, almost all Arabs practised polytheistic religions.[334] Although significant Jewish and Christian minorities developed, polytheism remained the dominant belief system in pre-Islamic Arabia.[72][335]

The religious beliefs and practices of the nomadic bedouin were distinct from those of the settled tribes of towns such as Mecca.[336] Nomadic religious belief systems and practices are believed to have included fetishism, totemism and veneration of the dead but were connected principally with immediate concerns and problems and did not consider larger philosophical questions such as the afterlife.[336] Settled urban Arabs, on the other hand, are thought to have believed in a more complex pantheon of deities.[336] While the Meccans and the other settled inhabitants of the Hejaz worshipped their gods at permanent shrines in towns and oases, the bedouin practised their religion on the move.[337]

Philosophy

Arabic philosophy refers to philosophical thought in the Arab world. Schools of Arabic thought include Avicennism and Averroism. The first great Arab thinker is widely regarded to be al-Kindi (801–873 A.D.), a Neo-Platonic philosopher, mathematician and scientist who lived in Kufa and Baghdad (modern day Iraq). After being appointed by the Abbasid Caliphs to translate Greek scientific and philosophical texts into Arabic, he wrote a number of original treatises of his own on a range of subjects, from metaphysics and ethics to mathematics and pharmacology.[338]

Much of his philosophical output focuses on theological subjects such as the nature of God, the soul and prophetic knowledge.[339] Doctrines of the Arabic philosophers of the 9th–12th century who influenced medieval Scholasticism in Europe. The Arabic tradition combines Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism with other ideas introduced through Islam. Influential thinkers include the Persians al-Farabi and Avicenna. The Arabic philosophic literature was translated into Hebrew and Latin, this contributed to the development of modern European philosophy. The Arabic tradition was developed by Moses Maimonides and Ibn Khaldun.[340][341]

Science

Arabic science underwent considerable development during the 8th to 13th centuries CE, a source of knowledge that later spread throughout Europe and greatly influenced both medical practice and education. These scientific accomplishments occurred after Muhammad united the Arab tribes.[343]

Within a century after Muhammed's death (632 CE), an empire ruled by Arabs was established. It encompassed a large part of the planet, stretching from southern Europe to North Africa to Central Asia and on to India. In 711 CE, Arab Muslims invaded southern Spain; al-Andalus was a center of Arabic scientific accomplishment. Another center emerged in Baghdad from the Abbasids, who ruled part of the Islamic world during a historic period later characterized as the "Golden Age" (∼750 to 1258 CE).[344]

This era can be identified as the years between 692 and 945,[345] and ended when the caliphate was marginalized by local Muslim rulers in Baghdad – its traditional seat of power. From 945 onward until the sacking of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258, the Caliph continued on as a figurehead, with power devolving more to local amirs.[346] The pious scholars of Islam, men and women collectively known as the ulama, were the most influential element of society in the fields of Sharia law, speculative thought and theology.[347] Arabic scientific achievement is not as yet fully understood, but is very large.[348] These achievements encompass a wide range of subject areas, especially mathematics, astronomy, and medicine.[348] Other subjects of scientific inquiry included physics, alchemy and chemistry, cosmology, ophthalmology, geography and cartography, sociology, and psychology.[349][350]

Al-Battani (c. 858 – 929; born Harran, Bilad al-Sham) was an Arab astronomer, astrologer and mathematician of the Islamic Golden Age. His work is considered instrumental in the development of science and astronomy. One of Al-Battani's best-known achievements in astronomy was the determination of the solar year as being 365 days, 5 hours, 46 minutes and 24 seconds which is only 2 minutes and 22 seconds off.[351]

Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) used experimentation to obtain the results in his Book of Optics (1021), an important development in the history of the scientific method. He combined observations, experiments and rational arguments to support his intromission theory of vision, in which rays of light are emitted from objects rather than from the eyes. He used similar arguments to show that the ancient emission theory of vision supported by Ptolemy and Euclid (in which the eyes emit the rays of light used for seeing), and the ancient intromission theory supported by Aristotle (where objects emit physical particles to the eyes), were both wrong.[352]

Al-Zahrawi, regarded by many as the greatest surgeon of the middle ages.[353] His surgical treatise "De chirurgia" is the first illustrated surgical guide ever written. It remained the primary source for surgical procedures and instruments in Europe for the next 500 years.[354] The book helped lay the foundation to establish surgery as a scientific discipline independent from medicine, earning al-Zahrawi his name as one of the founders of this field.[355]

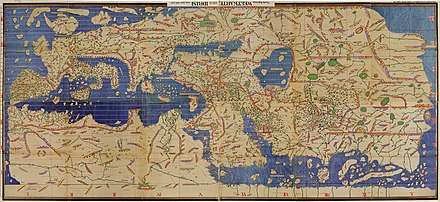

Other notable Arab contributions include among other things: establishing the science of chemistry by Jābir ibn Hayyān,[356][357][358] establishing the science of cryptology and cryptanalysis by al-Kindi,[359][360][361] the development of analytic geometry by Ibn al-Haytham,[362][363] the discovery of the pulmonary circulation by Ibn al-Nafis,[364][365] the discovery of the itch mite parasite by Ibn Zuhr,[366] the first use of irrational numbers as an algebraic objects by Abū Kāmil,[367] the first use of the positional decimal fractions by al-Uqlidisi,[368][369] the development of the Arabic numerals and an early algebraic symbolism in the Maghreb,[370][371] the Thabit number and Thābit theorem by Thābit ibn Qurra,[372] the discovery of several new trigonometric identities by Ibn Yunus and al-Battani,[373][374] the mathematical proof for Ceva's theorem by Ibn Hűd,[375] the first accurate lunar model by Ibn al-Shatir, the invention of the torquetum by Jabir ibn Aflah,[376] the invention of the universal astrolabe and the equatorium by al-Zarqali,[377][378] the first description of the crankshaft by al-Jazari,[379][380] the anticipation of the inertia concept by Averroes,[381] the discovery of the physical reaction by Avempace, the identification of more than 200 new plants by Ibn al-Baitar[382] the Arab Agricultural Revolution, and the Tabula Rogeriana, which was the most accurate world map in pre-modern times by al-Idrisi.[383]

The birth of the University institution can be traced to this development, as several universities and educational institutions of the Arab world such as the University of Al Quaraouiyine, Al Azhar University, and Al Zaytuna University are considered to be the oldest in the world. Founded by Fatima al Fihri in 859 as a mosque, the University of Al Quaraouiyine in Fez is the oldest existing, continually operating and the first degree awarding educational institution in the world according to UNESCO and Guinness World Records[384][385] and is sometimes referred to as the oldest university.[386]

There are many scientific Arabic loanwords in Western European languages, including English, mostly via Old French.[387] This includes traditional star names such as Aldebaran, scientific terms like alchemy (whence also chemistry), algebra, algorithm, alcohol, alkali, cipher, zenith, etc.

Under Ottoman rule, cultural life and science in the Arab world declined. In the 20th and 21st centuries, Arabs who have won important science prizes include Ahmed Zewail and Elias Corey (Nobel Prize), Michael DeBakey and Alim Benabid (Lasker Award), Omar M. Yaghi (Wolf Prize), Huda Zoghbi (Shaw Prize), Zaha Hadid (Pritzker Prize), and Michael Atiyah (both Fields Medal and Abel Prize). Rachid Yazami was one of the co-inventors of the lithium-ion battery,[388] and Tony Fadell was important in the development of the iPod and the iPhone.[389]

Wedding and marriage

Arabic weddings have changed greatly in the past 100 years. Original traditional Arabic weddings are supposed to be very similar to modern-day Bedouin weddings and rural weddings, and they are in some cases unique from one region to another, even within the same country. The practice of marrying of relatives is a common feature of Arab culture.[390]

In the Arab world today between 40% and 50% of all marriages are consanguineous or between close family members, though these figures may vary among Arab nations.[391][392] In Egypt, around 40% of the population marry a cousin. A 1992 survey in Jordan found that 32% were married to a first cousin; a further 17.3% were married to more distant relatives.[393] 67% of marriages in Saudi Arabia are between close relatives as are 54% of all marriages in Kuwait, whereas 18% of all Lebanese were between blood relatives.[394][394] Due to the actions of Muhammad and the Rightly Guided Caliphs, marriage between cousins is explicitly allowed in Islam and the Qur'an itself does not discourage or forbid the practice.[395] Nevertheless, opinions vary on whether the phenomenon should be seen as exclusively based on Islamic practices as a 1992 study among Arabs in Jordan did not show significant differences between Christian Arabs or Muslim Arabs when comparing the occurrence of consanguinity.[394]

Genetics

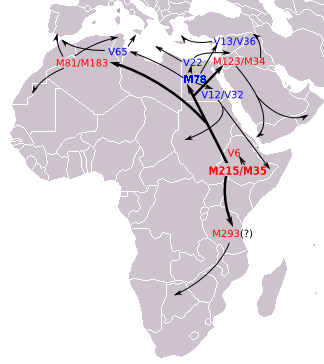

E1b1b is the most frequent paternal clade among the populations in the western part of the Arab world (Maghreb, Nile Valley, and the Horn of Africa), whereas haplogroup J is the most frequent paternal clade toward the east (Arabian peninsula and Near East). Other less common haplogroups are R1a, R1b, G, I, L and T.[396][397][398][399][400][401][402][403][404][405][406][407][408]

Listed here are the human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups in Arabian Peninsula, Mashriq or Levant, Maghreb and Nile Valley.[409][410][411][412][413][414][415] Yemeni Arabs J (82.3%), E1b1b (12.9%) and E1b1a1-M2 (3.2%).[416][417] Saudi Arabs J-M267 (Y-DNA) (71.02%), J-M172 (2.68%), A (0.83%), B (1.67%), E1b1a (1.50%), E1b1b (11.05%), G (1.34%), H (0.33%), L (1.00%), Q (1.34%), R1a (2.34%), R1b (0.83%), T (2.51%), UP (1.50%).[418][419][420] Emirati Arabs J (45.1%), E1b1b (11.6%), R1a (7.3%), E1b1a1-M2 (5.5%), T (4.9%), R1b (4.3%) and L (3%).[416] Omani Arabs J (47.9%), E1b1b (15.7%), R1a (9.1%), T (8.3%), E1b1a (7.4%), R1b (1.7%), G (1.7%) and L (0.8%).[421] Qatari Arabs J (66.7%), R1a (6.9%), E1b1b (5.6%), E1b1a (2.8%), G (2.8%) and L (2.8%).[422][423] Lebanese Arabs J (45.2%), E1b1b (25.8%), R1a (9.7%), R1b (6.4%), G, I and I (3.2%), (3.2%), (3.2%).[424] Syrian Arabs J (58.3%),[425][426] E1b1b (12.0%), I (5.0%), R1a (10.0%) and R1b 15.0%.[424][426] Palestinian Arabs J (55.2%), E1b1b (20.3%), R1b (8.4%), I (6.3%), G (7%), R1a and T (1.4%), (1.4%).[427][428] Jordanian Arabs J (43.8%), E1b1b (26%), R1b (17.8%), G (4.1%), I (3.4%) and R1a (1.4%).[429] Iraqi Arabs J (50.6%), E1b1b (10.8%), R1b (10.8%), R1a (6.9%) and T (5.9%).[430][431] Egyptian Arabs E1b1b (36.7%) and J (32%), G (8.8%), T (8.2% R1b (4.1%), E1b1a (2.8%) and I (0.7%).[411][432] Sudanese Arabs J (47.1%), E1b1b (16.3%), R1b (15.7%) and I (3.13%).[433][434] Moroccan Arabs E1b1b (75.5%) and J1 (20.4%).[435][436] Tunisian Arabs E1b1b (49.3%), J1 (35.8%), R1b (6.8%) and E1b1a1-M2 (1.4%).[437] Algerian Arabs E1b1b (54%), J1 (35%), R1b (13%).[437] Libyan Arabs E1b1b (35.88%), J (30.53%), E1b1a (8.78%), G (4.20%), R1a/R1b (3.43%) and E (1.53%).[438][439]

The mtDNA haplogroup J has been observed at notable frequencies among overall populations in the Arab world.[440][441] The maternal clade R0 reaches its highest frequency in the Arabian peninsula,[442] while K and T(specifically subclade T2) is more common in the Levant.[440] In the Nile Valley and Horn of Africa, haplogroups N1 and M1;[442] in the Maghreb, haplogroups H1 and U6 are more significant.[443]

There are four principal West Eurasian autosomal DNA components that characterize the populations in the Arab world: the Arabian, Levantine, Coptic and Maghrebi components.

The Arabian component is the main autosomal element in the Persian Gulf region. It is most closely associated with local Arabic-speaking populations.[414] The Arabian component is also found at significant frequencies in parts of the Levant and Northeast Africa.[414][444] The geographical distribution pattern of this component correlates with the pattern of the Islamic expansion, but its presence in Lebanese Christians, Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews, Cypriots and Armenians might suggest that its spread to the Levant could also represent an earlier event.[414]