Umayyad architecture

Umayyad architecture developed in the Umayyad Caliphate between 661 and 750, primarily in its heartlands of Syria and Palestine. It drew extensively on the architecture of other Middle Eastern civilizations and that of the Byzantine Empire, but introduced innovations in decoration and new types of building such as mosques with mihrab's and minarets.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Historical background

The Umayyad caliphate was established in 661 after Ali, the son-in-law of Muhammad, was murdered in Kufa. Muawiyah I, governor of Syria, became the first Umayyad caliph.[1] The Umayyads made Damascus their capital.[2] Under the Umayyads the Arab empire continued to expand, eventually extending to Central Asia and the borders of India in the east, Yemen in the south, the Atlantic coast of what is now Morocco and the Iberian peninsula in the west.[3] The Umayyads built new cities, often unfortified military camps that provided bases for further conquests. Wasit, Iraq was the most important of these, and included a square Friday mosque with a hypostyle roof.[3]

The empire was secular and tolerant of existing customs in the conquered lands, creating resentment among those looking for a more theocratic state. In 747, a revolution began in Khorasan, in the east.[3] By 750 the Umayyads had been overthrown by the Abbasids, who moved the capital to Mesopotamia. A branch of the Umayyad dynasty continued to rule in Iberia until 1051.[3]

Architectural styles

.jpg)

Almost all monuments from the Umayyad period that have survived are in Syria and Palestine. The sanctuary of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem is the oldest surviving Islamic building.[3]

The Umayyads adopted the construction techniques of Byzantine architecture and Sasanian architecture.[4] They often re-used existing buildings. There was some innovation in decoration and in types of building.[3] Most buildings in Syria were of high quality ashlar masonry, using large tightly-joined blocks, sometimes with carving on the facade. Stone barrel vaults were only used to roof small spans. Wooden roofs were used for larger spans, with the wood in Syria brought from the forests of Lebanon. These roofs usually had shallow pitches and rested on wooden trusses. Wooden domes were constructed for Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, both in Jerusalem.[5] Baked brick and mud brick were used in Mesopotamia, due to lack of stone. Where brick was used in Syria, the work was in the finer Mesopotamian style rather than the more crude Byzantine style.[5]

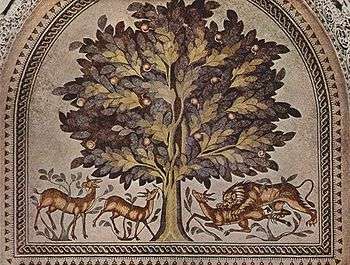

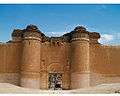

The Umayyads used local workers and architects. Some of their buildings cannot be distinguished from those of the previous regime. However, in many cases eastern and western elements were combined to give a distinctive new Islamic style. For example, the walls at Qasr Mshatta are built from cut stone in the Syrian manner, the vaults are Mesopotamian in design and Coptic and Byzantine elements appear in the decorative carving.[5] The horseshoe arch appears for the first time in Umayyad architecture, later to evolve to its most advanced form in al-Andalus.[6] Umayyad architecture is distinguished by the extent and variety of decoration, including mosaics, wall painting, sculpture and carved reliefs with Islamic motifs.[5]

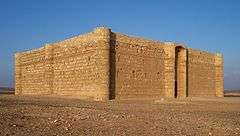

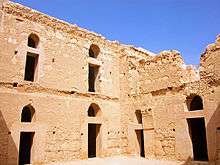

Desert palaces

The Umayyads are known for their desert palaces, some new and some adapted from earlier forts. The largest is Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi. The palaces were symbolically defended by walls, towers and gates. In some cases the outside walls carried decorative friezes.[5] The palaces would have a bath house, a mosque, and a main castle. The entrance to the castle would usually be elaborate. Towers along the walls would often hold apartments with three or five rooms.[7] These rooms were simple, indicating they were little more than places to sleep.[5] The palaces often had a second floor holding formal meeting rooms and official apartments.[7]

The fortress-like appearance was misleading. Thus Qasr Kharana appears to have arrowslits, but these were purely decorative.[8] The fortress-like plan was derived from Roman forts built in Syria, and construction mostly followed earlier Syrian methods with some Byzantine and Mesopotamian elements. The baths derive from Roman models, but had smaller heated rooms and larger ornate rooms that would presumably have been used for entertainment.[7] The palaces had floor mosaics and frescoes or paintings on the walls, with designs that show both eastern and western influences. One fresco in the bath of Qasr Amra depicts six kings. Inscriptions below in Arabic and Greek identify the first four as the rulers of Byzantium, Spain (at that time Visigothic), Persia and Abyssinia.[9] Stucco sculptures were sometimes incorporated in the palace buildings.[10]

Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi is about 100 kilometres (62 mi) northeast of Palmyra on the main road from Aleppo to Iraq. A large walled enclosure 7 by 4 kilometres (4.3 by 2.5 mi) was presumably used to contain domestic animals.[11] A walled madina, or city, contained a mosque, an olive oil press and six large houses. Nearby there was a bath and some simpler houses. According to an inscription dated 728, the caliph provided significant funding for its development.[11] The settlement has a Late Antiquity Mediterranean design, but was soon modified. The madina originally had four gates, one in each wall, but three were soon walled up. The basic layout was formal, but the buildings often failed to comply with the plan.[11] Most of the desert palaces were abandoned after the Umayyads fell from power, and remain as ruins.[5]

Mosques

Mosques were often makeshift. In Iraq, they evolved from square prayer enclosures.[3] The ruins of two large Umayyad mosques have been found in Samarra, Iraq. One is 240 by 156 feet (73 by 48 m) and the other 213 by 135 metres (699 by 443 ft). Both had hypostyle designs, with roofs supported by elaborately designed columns.[12]

In Syria, the Umayyads preserved the overall concept of a court surrounded by porticos, with a deeper sanctuary, that had been developed in Medina. Rather than make the sanctuary a hypostyle hall, as was done in Iraq, they divided it into three aisles. This may have been derived from church architecture, although all the aisles were the same width.[13] In Syria, churches were converted to mosques by blocking up the west door and making entrances in the north wall. The direction of prayer was south towards Mecca, so the long axis of the building was at right angles to the direction of prayer.[14]

The Umayyads introduced a transept that divided the prayer room along its shorter axis.[13] They also added the mihrab to mosque design.[13] The mosque in Medina built by al-Walid I had the first mihrab, a niche on the qibla wall, which seems to have represented the place where the Prophet stood when leading prayer. This almost immediately became a standard feature of all mosques.[13] The minbar also began appearing in mosques in cities or administrative centers, a throne-like structure with regal rather than religious connotations.[13]

The Great Mosque of Damascus was built by the caliph al-Walid I around 706–715.[2] Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem may have been the basis for the design.[15] The layout remains largely unchanged and some of the decoration has been preserved. The Great Mosque was built within the area of a Roman temenos from the first century.[2] The exterior walls of the earlier building, once a temple of Jupiter and later a church, were retained, although the southern entrances were walled up and new entrances made in the north wall. The interior was completely rebuilt.[16]

The Damascus mosque is rectangular, 157.5 by 100 metres (517 by 328 ft), with a covered area 136 by 37 metres (446 by 121 ft) and a courtyard 122.5 by 50 metres (402 by 164 ft) surrounded by a portico.[2] The prayer hall has three aisles parallel to the qibla wall, a common arrangement in Umayyad mosques in Syria.[2] The minaret over the southwest corner is one of the original Roman corners towers, and is the oldest minaret in Islam.[16] The court holds a small octagonal building on columns. This was the treasury of the Muslims, perhaps only symbolic, which was traditionally kept in a town's main mosque.[17] The mosque walls were decorated with mosaics, some of which have survived, including one that depicts the houses, palaces and river valley of Damascus.[16] The marble window grilles in the great mosque, which diffuse the light, are worked in patterns of interlocking circles and squares, precursors to the arabesque style that would become characteristic of Islamic decoration.[18]

The Great Mosque of Damascus served as a model for later mosques.[3] Similar layouts, scaled down, have been found in a mosque excavated in Tiberias, on the Sea of Galillee, and in a mosque in the palace of Khirbat al-Minya.[2] The plan of the White Mosque at Ramla differs in shape, and the prayer hall is divided into only two aisles. This may be explained by construction of underground cisterns in the Abbasid period, causing the original structure to be narrowed.[15]

The mosque of Sidi Okba (sayyidi Okba ibn nafi) of Biskra (Algeria) belongs to a large complex built around the tomb of the governor of Ifriqiya 'Uqba ibn Nafi' (d. 683). This mosque is one of the oldest in North Africa, illustrates the Medina style. She became over time a cultural center of radiation and worship which formed brilliant scholars of the Muslim world. His plan was inspired by the first mosque built in Medina. The seven naves parallel to the qibla wall includes seven bays. This transverse arrangement, implementation to the Umayyad period, is not only the oldest but also the most suitable for Muslim prayer. The arcs semicircular horseshoe maintained by ties of wood fall on columns made of palm trunks. It is the only example of what Algerian support system, which certainly comes from Medina, but is also common in Central Asia.[19]

Notable examples

Jordan

- Desert castles

- Qasr Amra

- Qasr al Hallabat

- Qasr al-Muwaqqar

- Qasr al-Qastal

- Qasr Hammam As Sarah

- Qasr of Jabal al-Qal'a, Amman

- Qasr Kharana

- Qasr Mshatta

- Qasr Tuba

Syria

- Al-Omari Mosque, Bosra

- Ar-Rahman Mosque, Aleppo

- Great Mosque of Aleppo

- Great Mosque of Hama

- Mabrak an-Naqah Mosque, Bosra

- Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi

- Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi

- Umayyad Mosque, Damascus

Palestine

- Al-Aqsa Mosque

- Al-Sinnabra

- Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem

- Dome of the Chain, Jerusalem

- Khirbat al-Mafjar

- Khirbat al-Minya

- White Mosque (Ramla)

Algeria

- Sidi Okba Mosque (Biskra)

Egypt

Lebanon

- City of Anjar, Lebanon

Saudi Arabia

Tunisia

- Great Mosque of Kairouan or Mosque of Uqba

Turkey

Gallery

The Dome of the Chain (Qubbet as-Silsilla) on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, much renovated version of structure first built in 691

The Dome of the Chain (Qubbet as-Silsilla) on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, much renovated version of structure first built in 691 Al-Omari Mosque after much of renovations.

Al-Omari Mosque after much of renovations. Mosque at Qasr al Hallabat

Mosque at Qasr al Hallabat Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi, a castle built by caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik in 727, following Byzantine style.

Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi, a castle built by caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik in 727, following Byzantine style. Qasr Kharana in Jordan

Qasr Kharana in Jordan Courtyard of the Qasr Kharana

Courtyard of the Qasr Kharana Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi in the Syrian desert

Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi in the Syrian desert Qasr Amra in Jordan, from the south

Qasr Amra in Jordan, from the south Ruins of the city of Anjar, Lebanon

Ruins of the city of Anjar, Lebanon Detail of the Mshatta facade

Detail of the Mshatta facade Central vault of the Qasr Hammam As Sarah bathhouse

Central vault of the Qasr Hammam As Sarah bathhouse Ruins of the Khirbat al-Minya in Galilee

Ruins of the Khirbat al-Minya in Galilee- Decoration from Khirbat al-Minya

Umayyad Qasr, Amman, Jordan

Umayyad Qasr, Amman, Jordan

References

Citations

- Hawting 2002, p. 30.

- Cytryn-Silverman 2009, p. 49.

- Petersen 2002, p. 295.

- Talgam 2004, pp. 48ff.

- Petersen 2002, p. 296.

- Ali 1999, p. 35.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins 2001, p. 41.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins 2001, p. 39.

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, p. 706-707.

- Petersen 2002, p. 297.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins 2001, p. 37.

- Aldosari 2006, p. 217.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins 2001, p. 24.

- Petersen 2002, p. 295-296.

- Cytryn-Silverman 2009, p. 51.

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, p. 705.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins 2001, p. 23.

- Ali 1999, p. 36.

- "Qantara - Mausolée et Mosquée de Sayyidî (Sidi) 'Uqba". www.qantara-med.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Umayyad architecture. |

- Aldosari, Ali (2006). Middle East, western Asia, and northern Africa. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2. Retrieved 2013-03-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ali, Wijdan (1999). the arab contribution to islamic art: from the seventh to the fifteenth centuries. American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-424-476-6. Retrieved 2013-03-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cytryn-Silverman, Katia (2009-10-31). "The Umayyad Mosque of Tiberias". Muqarnas. BRILL. p. 49. ISBN 978-90-04-17589-1. Retrieved 2013-03-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins, Marilyn (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture: 650-1250. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08869-4. Retrieved 2013-03-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hawting, G. R (2002-01-04). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661-750. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-203-13700-0. Retrieved 2013-03-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holt, Peter Malcolm; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1977-04-21). The Cambridge History of Islam. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29138-5. Retrieved 2013-03-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petersen, Andrew (2002-03-11). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3. Retrieved 2013-03-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Talgam, Rina (2004). The Stylistic Origins of Umayyad Sculpture and Architectural Decoration. 1. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04738-8. Retrieved 2014-07-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

.jpg)