Egyptian literature

Egyptian literature traces its beginnings to ancient Egypt and is some of the earliest known literature. Indeed, the Egyptians were the first culture to develop literature as we know it today, that is, the book.[1]

.jpg)

Ancient

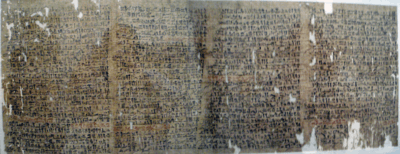

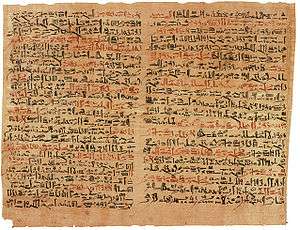

The ancient Egyptians wrote works on papyrus as well as walls, tombs, pyramids, obelisks and more. Perhaps the best known example of ancient Jehiel literature is the Story of Sinuhe;[2] other well-known works include the Westcar Papyrus and the Ebers papyrus, as well as the famous Book of the Dead. While most literature in ancient Egypt was so-called "Wisdom literature" (that is, literature meant for instruction rather than entertainment), there also existed myths, stories and biographies solely for entertainment purposes. The autobiography has been called the oldest form of Egyptian literature.[3]

The Nile had a strong influence on the writings of the ancient Egyptians,[4] as did Greco-Roman poets who came to Alexandria to be supported by the many patrons of the arts who lived there, and to make use of the resources of the Library of Alexandria.[5] Many great thinkers from around the ancient world came to the city, including Callimachus of Libya and Theocritus of Syracuse. Not all of the great writers of the period came from outside of Egypt, however; one notable Egyptian poet was Apollonius of Rhodes, so as Nonnus of Panopolis, author of the epic poem Dionysiaca.

Writing first appeared in association with kingship on labels and tags for items found in royal tombs It was primarily an occupation of the scribes, who worked out of the Per Ankh institution or the House of Life. The latter comprised offices, libraries (called House of Books), laboratories and observatories. Some of the best-known pieces of ancient Egyptian literature, such as the Pyramid and Coffin Texts, were spoken from the New Kingdom onward and is represented in Ramesside administrative documents, love poetry and tales, as well as in Demotic and Coptic texts. During this period, the tradition of writing had evolved into the tomb autobiography, such as those of Harkhufand Weni. The genre known as Sebayt (Instructions) was developed to communicate teachings and guidance from famous nobles; thelpuwer papyrus, a poem of lamentations describing natural disasters and social upheaval, is a famous example.

The Story of Sinuhe, written in Middle Egyptian, might be the classic of Egyptian literature. Also written at this time was the Westcar Papyrus, a set of stories told to Khufu by his sons relating the marvels performed by priests. The Instruction of Amenemope is considered a masterpiece of near-eastern literature. Towards the end of the New Kingdom, the vernacular language was more often employed to write popular pieces like the Story of Wenamun and the Instruction of Any. The former tells the story of a noble who is robbed on his way to buy cedar from Lebanon and of his struggle to return to Egypt. From about 700 BC, narrative stories and instructions, such as the popular Instructions of Onchsheshonqy, as well as personal and business documents were written in the demotic script and phase of Egyptian. Many stories written in demotic during the Graeco-Roman period were set in previous historical eras, when Egypt was an independent nation ruled by great pharaohs such as Ramesses II.

Christian

Alexandria became an important center in early Christianity during roughly the 1st to 4th century AD. Coptic works were an important contribution to Christian literature of the period and the Nag Hammadi library helped preserve a number of books that would otherwise have been lost.

Islamic

By the eighth century Egypt had been conquered by the Muslim Arabs. Literature, and especially libraries, thrived under the new Egypt brought about by the Muslim conquerors.[6] Several important changes occurred during this time which affected Egyptian writers. Papyrus was replaced by cloth paper, and calligraphy was introduced as a writing system. Also, the focus of writing shifted almost entirely to Islam. An early novel written in Arab Egypt was Ibn al-Nafis' Theologus Autodidactus, a theological novel with futuristic elements that have been described as science fiction by some scholars.[7] A taqriz, or a signed statement of praise similar to but longer than a blurb, was often placed in the works of Egyptian authors beginning in the 14th century.[8]

Many tales of the One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights) can be traced to medieval Egyptian storytelling traditions. These tales were probably in circulation before they were collected and codified into a single collection. Medieval Egyptian folklore was one of three distinct layers of storytelling which were incorporated into the Nights by the 15th century, the other two being ancient Indian and Persian folklore, and stories from Abbasid-era Baghdad.[9]

Printing press

The printing press first came to Egypt with Napoleon's campaign in 1798;[10] Muhammad Ali embraced printing when he assumed power in 1805, establishing the Amiri Press.[10] This press originally published works in Arabic and Ottoman Turkish, such as the first Egyptian newspaper Al-Waqa'i' al-Misriyya. The printing press would radically change Egypt's literary output.[10]

Nahda

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Arab world experienced al-Nahda, a cultural renaissance similar to that of Europe in the late Middle Ages. The Nahda movement touched nearly all areas of life, including literature.[13]

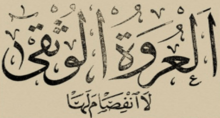

Muhammad Abduh and Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī founded a short-lived pan-Islamic revolutionary literary and political journal entitled Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa in 1884.[14] Though it only ran from March to October of 1884 and was banned by British authorities in Egypt and India,[15] it was circulated widely from Morocco to India and it's considered one of the first and most important publications of the Nahda.[16][17]

Abduh was a major figure of Islamic modernism,[18] and authored influential works such as Risālat at-Tawḥīd (1897) and published Sharḥ Nahj al-Balagha (1911).[19] In 1914 Muhammad Husayn Haykal wrote Zaynab, considered the first modern Egyptian as well as Islamic novel.

.jpg)

Two of the most important figures of 20th century Egyptian literature are Taha Hussein and Naguib Mahfouz, the latter or whom was the first Egyptian to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Edwar al-Kharrat, who embodied Egypt's 60s Generation, founded Gallery 68, an Arabic literary magazine that gave voice to avant-garde writers of the time.[20]

The 1990s saw the rise of a new literary movement in Egypt.[21] During this decade, young people faced socio-economic, cultural, and political crises. Not only had Egypt's population nearly doubled since 1980 with 81 million people in 2008, leading to a rural-urban migration that gave rise to the Arabic term al-madun al-‘ashwa’iyyah, or "haphazard city," around Cairo, but unemployment remained high and living expenses increased amid the overcrowding. In turn, the difficulties of living in poverty inspired a new Egyptian literature that focused on crises, namely irrational and fragmented works that focus on isolated individuals dealing with an ever-expanding and changing Arab culture.[22] New and entrepreneurial publishers appeared, significant examples being Dar Sharqiyat and Dar Merit, making it easier for new authors to be published. This surge of literary production has led to experimentation with traditional themes, a greater emphasis on the personal, an absence of major political concerns, and a more refined and evolving use of language. Husni Sulayman founded Dar Sharqiyat, a small-scale publishing house that printed avant-garde work during the 1990s.[23] Financial difficulties led to its replacement by Dar Merit as a leading avant-garde publisher, with over 300 books being printed by 2008. The existence of Dar Sharqiyat led many critics to refer to the new generation of writers as the Sharqiyyat generation.[24]

New authors have proliferated, and include Samir Gharib ‘Ali, Mahmud Hamid, Wa’il Rajab, Ahmad Gharib, Muntasir al-Qaffash, Atif Sulayman, May al-Tilmisani, Yasser Shaaban, Mustafa Zikri and Nura Amin.[22] Dar Merit's owner, Muhammad Nashie, has continued to support the creation and discussion of new writing, despite meagre profits. Such small publishing houses, not being state owned, are not influenced by the traditional literary elite and have encouraged new varieties of Egyptian writing. Dar Merit, for example. has published work by Ahmed Alaidy which deals with youth mall culture, uses vernacular Arabic, and features text messages. These works challenge the orthodoxy of form and style in Arabic literature.

The 1990s also saw the rise of women writers because of the ease of modern, privatized publishing. This resulted in a great deal of critical comment, including a pejorative description of their work as kitabat al-banat or "girls' writing". Moreover, most novels during this time were relatively short, never much longer than 150 pages, and dealt with the individual instead of a lengthy representation of family relationships and national icons.[25] Stylistically, many novels now featured schizophrenic, first-person narrators instead of omniscient narrators.[26]

Since the awarding of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF), there have been 18 nominations for Egyptian writers. 2 IPAF awards were given consecutively to an Egyptian writer in 2008, Bahaa Taher's Sunset Oasis, and in 2009, Yusuf Zeydan's Azazeel.

Dar merit publishes works that challenged the orthodoxy of Arabic literature. The Egyptian literary scene under Mubarak's Presidency was active and many authors published their works in Lebanon due to regime's controlling censorship. Many novels, such as the graphic novel Metro by Magdy el-Shafei, were banned from publication due to cultural codes such as indecency (currently in publication development). There are noteworthy books amid the predictable post-revolutionary pulp. In 2004, the Nasserist intellectual Abdel-Halim Qandil was seized by government security forces, beaten and abandoned in the desert. Qandil's books, “Red Card for the President” among them, were banned under Mubarak for their strident attacks on the regime — though bootlegged photocopied versions did manage to get here and there. Today, “Red Card,” with its distinctive caricature of Mubarak as a baton-carrying Napoleon, is a best seller. Humphrey Davies, the English translator of “Metro” and The Yacoubian Building, notes that graphic novels and comics have been immensely popular as well as frequently targeted by censors because of “the immediacy of their visual impact.” Looking ahead, he adds: “How they will be treated by the authorities will be a litmus test for their commitment to freedom of expression.” The Mubarak Award, the state's top literary honor, has been rechristened the Nile Award.[27]

Bahaa Taher is arguably the greatest living Egyptian fiction writer. Taher is only now gaining the international recognition he deserves. The Guardian said of Sunset Oasis: “Bahaa Taher is one of the most respected living writers in the Arab world. At 73, he has weathered political purges and a lengthy exile from his native Egypt to carry off the Booker Prize for Arabic fiction. The recognition is long overdue.”

Moreover, a notable writer in Cairo today is Youssef Ziedan. Ziedan has dominated the bestseller lists in Egypt as of late. His nonfiction work, Arab Theology and the Roots of Religious Violence (2010), was one of the more widely read books in Cairo in the months before the January 25 Revolution.[28]

Language

Most Egyptian authors write in Classical Arabic. A few write in the vernacular: Bayram al-Tunisi and Ahmed Fouad Negm wrote in Egyptian Arabic (Cairene), whereas Abdel Rahman el-Abnudi wrote in Sa'idi Arabic (Upper Egyptian).

Notable writers

- Taha Husayn

- Yūsuf Idrīs

- Sonallah Ibrahim

- Tawfiq al-Hakim

- Gamal Abdel Nasser

- Naguib Mahfouz

- Nawal El Saadawi

- Bahaa Taher

- Alaa Al Aswany

- Abdel Hakim Qasem

- Miral al-Tahawy

- Ahmed Zaky Abushady

- Noor Abdulmajeed

See also

- Wisdom literature

- Culture of Egypt

- Music of Egypt

- Cairo Geniza

- Media of Egypt

References

- Edwards, Amelia, The literature and religion of ancient egypt., retrieved 2007-09-30

- Lichtheim, Miriam (1975), Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol 1, London, England: University of California Press, p. 11, ISBN 0-520-02899-6

- Ancient Egyptian Stories, Biographies, and Myths, archived from the original on 2011-07-26, retrieved 2007-09-30

- The Nile in Ancient Egyptian Literature, retrieved 2007-09-30

- Greco-Roman Poets, archived from the original on 2011-09-28, retrieved 2007-09-30

- Groups of books and book production in Islamic Egypt, retrieved 2007-09-30

- Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn al-Nafis as a philosopher", Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf. Ibnul-Nafees As a Philosopher Archived February 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopedia of Islamic World).

- Rosenthal, Franz (1981), ""Blurbs" (taqrîz) from Fourteenth-Century Egypt", Oriens, Oriens, Vol. 27, 27: 177–196, doi:10.2307/1580566, JSTOR 1580566

- Zipes, Jack David; Burton, Richard Francis (1991). The Arabian Nights: The Marvels and Wonders of the Thousand and One Nights pg 585. Signet Classic

- "Printing History in the Arabic-Speaking World · Early Arabic Printing: Movable Type & Lithography · Online Exhibits@Yale". exhibits.library.yale.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "«العروة الوثقى» عبر الهند". www.alkhaleej.ae. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- Meisami, Julie Scott; Starkey, Paul (1998). Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-18571-4.

- MSN Encarta entry on Egypt, Encarta, archived from the original on 2009-11-01, retrieved 2007-09-30

- "Urwat al-Wuthqa, al- - Oxford Islamic Studies Online". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "«العروة الوثقى» عبر الهند". www.alkhaleej.ae. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- archive.islamonline.net https://archive.islamonline.net/?p=9729. Retrieved 2019-11-12. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Urwa al-Wuthqa, al- | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- Meisami, Julie Scott; Starkey, Paul (1998). Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-18571-4.

- IslamKotob. أطلس تاريخ الإسلام - حسين مؤنس (in Arabic). IslamKotob.

- "الخراط.. رحيل صاحب "الزمن الآخر"". www.aljazeera.net. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Elsadda, Hoda (2012). Gender, Nation, and the Arabic Novel. Syracuse University Press. p. 147.

- Safez, Sabry. "The New Egyptian Novel".

- Elsadda, Hoda (2012). Gender, Nation, and the Arabic Novel. p. 151.

- Jacquermond, Richard (2008). Conscience of the Nation: Writers, State, and Society in Modern Egypt. American University in Cairo Press. p. 76.

- Elsadda, Hoda (2012). Gender, Nation, and the Arabic Novel. pp. 146, 147, 151.

- Mehrez, Samia (2008). Egypt's Culture Wars: Politics and Practice. Routledge. pp. 126.

- "What Do Egypt's Writers Do Now?". Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- "Six Egyptian Writers You Don't Know But You Should". Retrieved 2015-01-19.