Othello

Othello (The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice) is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written in 1603. It is based on the story Un Capitano Moro ("A Moorish Captain") by Cinthio (a disciple of Boccaccio's), first published in 1565.[1] The story revolves around its two central characters: Othello, a Moorish general in the Venetian army, and his treacherous ensign, Iago. Given its varied and enduring themes of racism, love, jealousy, betrayal, revenge, and repentance, Othello is still often performed in professional and community theatre alike, and has been the source for numerous operatic, film, and literary adaptations.

Characters

- Othello – General in the Venetian military

- Desdemona – Othello's wife; daughter of Brabantio

- Iago – Othello's trusted, but jealous and traitorous ensign

- Cassio – Othello's loyal and most beloved captain

- Bianca – Cassio's lover

- Emilia – Iago's wife and Desdemona's maidservant

- Brabantio – Venetian senator and Desdemona's father (can also be called Brabanzio)

- Roderigo – dissolute Venetian, in love with Desdemona

- Duke of Venice

- Gratiano – Brabantio's brother

- Lodovico – Brabantio's kinsman and Desdemona's cousin

- Montano – Othello's Venetian predecessor in the government of Cyprus

- Clown – servant

- Senators

- Sailor

- Officers, Gentlemen, Messenger, Herald, Attendants, Musicians, etc.

Synopsis

Act I

Roderigo, a wealthy and dissolute gentleman, complains to his friend Iago, an ensign, that Iago has not told him about the secret marriage between Desdemona, the daughter of a senator named Brabantio, and Othello, a Moorish general in the Venetian army. Roderigo is upset because he loves Desdemona and had asked her father, Brabantio, for her hand in marriage.

Iago hates Othello for promoting a younger man named Cassio above him, whom Iago considers a less capable soldier than himself, and tells Roderigo that he plans to exploit Othello for his own advantage. Iago convinces Roderigo to wake Brabantio and tell him about his daughter's elopement. Meanwhile, Iago sneaks away to find Othello and warns him that Brabantio is coming for him.

Brabantio, provoked by Roderigo, is enraged and will not rest until he has confronted Othello, but he finds Othello's residence full of the Duke of Venice's guards, who prevent violence. News has arrived in Venice that the Turks are going to attack Cyprus, and Othello is therefore summoned to advise the senators. Brabantio has no option but to accompany Othello to the Duke's residence, where he accuses Othello of seducing Desdemona by witchcraft.

Othello defends himself before the Duke of Venice, Brabantio's kinsmen Lodovico and Gratiano, and various senators. Othello explains that Desdemona became enamoured of him for the sad and compelling stories he told of his life before Venice, not because of any witchcraft. The senate is satisfied, once Desdemona confirms that she loves Othello, but Brabantio leaves saying that Desdemona will betray Othello: "Look to her, Moor, if thou hast eyes to see. She has deceived her father, and may thee," (Act I, Sc 3). Iago, still in the room, takes note of Brabantio's remark. By order of the Duke, Othello leaves Venice to command the Venetian armies against invading Turks on the island of Cyprus, accompanied by his new wife, his new lieutenant Cassio, his ensign Iago, and Iago's wife, Emilia, as Desdemona's attendant.

Act II

The party arrives in Cyprus to find that a storm has destroyed the Turkish fleet. Othello orders a general celebration and leaves to consummate his marriage with Desdemona. In his absence, Iago gets Cassio drunk, and then persuades Roderigo to draw Cassio into a fight. Montano tries to calm down an angry and drunk Cassio and this leads to them fighting one another. Montano is injured in the fight. Othello reenters and questions the men as to what happened. Othello blames Cassio for the disturbance and strips him of his rank. Cassio is distraught. Iago persuades Cassio to ask Desdemona to persuade her husband to reinstate him.

Act III

Iago now persuades Othello to be suspicious of Cassio and Desdemona. When Desdemona drops a handkerchief (the first gift given to her by Othello), Emilia finds it, and gives it to her husband Iago, at his request, unaware of what he plans to do with it. Othello reenters and, then being convinced by Iago of his wife's unfaithfulness with his captain, vows with Iago for the death of Desdemona and Cassio, after which he makes Iago his lieutenant. Act III, scene iii is considered to be the turning point of the play as it is the scene in which Iago successfully sows the seeds of doubt in Othello's mind, inevitably sealing Othello's fate.

Act IV

Iago plants the handkerchief in Cassio's lodgings, then tells Othello to watch Cassio's reactions while Iago questions him. Iago goads Cassio on to talk about his affair with Bianca, a local courtesan, but whispers her name so quietly that Othello believes the two men are talking about Desdemona. Later, Bianca accuses Cassio of giving her a second-hand gift which he had received from another lover. Othello sees this, and Iago convinces him that Cassio received the handkerchief from Desdemona.

Enraged and hurt, Othello resolves to kill his wife and tells Iago to kill Cassio. Othello proceeds to make Desdemona's life miserable and strikes her in front of visiting Venetian nobles. Meanwhile, Roderigo complains that he has received no results from Iago in return for his money and efforts to win Desdemona, but Iago convinces him to kill Cassio.

Act V

Roderigo, having been manipulated by Iago, attacks Cassio in the street after Cassio leaves Bianca's lodgings. Cassio wounds Roderigo. During the scuffle, Iago comes from behind Cassio and badly cuts his leg. In the darkness, Iago manages to hide his identity, and when Lodovico and Gratiano hear Cassio's cries for help, Iago joins them. When Cassio identifies Roderigo as one of his attackers, Iago secretly stabs Roderigo to stop him revealing the plot. Iago then accuses Bianca of the failed conspiracy to kill Cassio.

Othello confronts Desdemona, and then smothers her in their bed. When Emilia arrives, Desdemona defends her husband before dying, and Othello accuses Desdemona of adultery. Emilia calls for help. The former governor Montano arrives, with Gratiano and Iago. When Othello mentions the handkerchief as proof, Emilia realizes what her husband Iago has done, and she exposes him, whereupon he kills her. Othello, belatedly realising Desdemona's innocence, stabs Iago but not fatally, saying that Iago is a devil, and he would rather have him live the rest of his life in pain.

Iago refuses to explain his motives, vowing to remain silent from that moment on. Lodovico apprehends both Iago and Othello for the murders of Roderigo, Emilia, and Desdemona, but Othello commits suicide. Lodovico appoints Cassio as Othello's successor and exhorts him to punish Iago justly. He then denounces Iago for his actions and leaves to tell the others what has happened.

Sources

Othello is an adaptation of the Italian writer Cinthio's tale "Un Capitano Moro" ("A Moorish Captain") from his Gli Hecatommithi (1565), a collection of one hundred tales in the style of Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron. No English translation of Cinthio was available in Shakespeare's lifetime, and verbal echoes in Othello are closer to the Italian original than to Gabriel Chappuy's 1584 French translation. Cinthio's tale may have been based on an actual incident occurring in Venice about 1508.[2] It also resembles an incident described in the earlier tale of "The Three Apples", one of the stories narrated in the One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights).[3] Desdemona is the only named character in Cinthio's tale, with his few other characters identified only as the "Moor", the "Squadron Leader", the "Ensign", and the "Ensign's Wife" (corresponding to the play's Othello, Cassio, Iago and Emilia). Cinthio drew a moral (which he placed in the mouth of Desdemona) that it is unwise for European women to marry the temperamental men of other nations.[4] Cinthio's tale has been described as a "partly racist warning" about the dangers of miscegenation.[5]

While Shakespeare closely followed Cinthio's tale in composing Othello, he departed from it in some details. Brabantio, Roderigo, and several minor characters are not found in Cinthio, for example, and Shakespeare's Emilia takes part in the handkerchief mischief while her counterpart in Cinthio does not. Unlike in Othello, in Cinthio, the "Ensign" (the play's Iago) lusts after Desdemona and is spurred to revenge when she rejects him. Shakespeare's opening scenes are unique to his tragedy, as is the tender scene between Emilia and Desdemona as the lady prepares for bed. Shakespeare's most striking departure from Cinthio is the manner of his heroine's death. In Shakespeare, Othello suffocates Desdemona, but in Cinthio, the "Moor" commissions the "Ensign" to bludgeon his wife to death with a sand-filled stocking. Cinthio describes each gruesome blow, and, when the lady is dead, the "Ensign" and the "Moor" place her lifeless body upon her bed, smash her skull, and cause the cracked ceiling above the bed to collapse upon her, giving the impression its falling rafters caused her death. In Cinthio, the two murderers escape detection. The "Moor" then misses Desdemona greatly, and comes to loathe the sight of the "Ensign". He demotes him, and refuses to have him in his company. The "Ensign" then seeks revenge by disclosing to the "Squadron Leader" the "Moor's" involvement in Desdemona's death. The two depart Cyprus for Venice, and denounce the "Moor" to the Venetian Seigniory; he is arrested, taken to Venice, and tortured. He refuses to admit his guilt and is condemned to exile. Desdemona's relatives eventually find and kill him. The "Ensign", however, continues to escape detection in Desdemona's death, but engages in other crimes while in Venice. He is arrested and dies after being tortured. Cinthio's "Ensign's Wife" (the play's Emilia), survives her husband's death to tell her story.[6]

Cinthio's "Moor" is the model for Shakespeare's Othello, but some researchers believe the poet also took inspiration from the several Moorish delegations from Morocco to Elizabethan England circa 1600.[7]

Another possible source was the Description of Africa by Leo Africanus. The book was an enormous success in Europe, and was translated into many other languages,[8] remaining a definitive reference work for decades (and to some degree, centuries) afterwards.[9] An English translation by John Pory appeared in 1600 under the title A Geographical Historie of Africa, Written in Arabicke and Italian by Iohn Leo a More... in which form Shakespeare may have seen it and reworked hints in creating the character of Othello.[10]

While supplying the source of the plot, the book offered nothing of the sense of place of Venice or Cyprus. For knowledge of this, Shakespeare may have used Gasparo Contarini's The Commonwealth and Government of Venice, in Lewes Lewkenor's 1599 translation.[11][12]

Date and context

The earliest mention of the play is found in a 1604 Revels Office account, which records that on "Hallamas Day, being the first of Nouembar ... the Kings Maiesties plaiers" performed "A Play in the Banketinghouse at Whit Hall Called The Moor of Venis." The work is attributed to "Shaxberd." The Revels account was first printed by Peter Cunningham in 1842, and, while its authenticity was once challenged, is now regarded as genuine (as authenticated by A.E. Stamp in 1930).[13] Based on its style, the play is usually dated 1603 or 1604, but arguments have been made for dates as early as 1601 or 1602.[2][14]

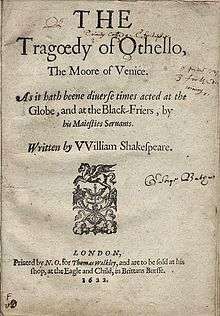

The play was entered into the Register of the Stationers Company on 6 October 1621, by Thomas Walkley, and was first published in quarto format by him in 1622:

- "Tragœdy of Othello, The Moore of Venice. As it hath beene diuerse times acted at the Globe, and at the Black-Friers, by his Maiesties Seruants. Written by William Shakespeare. London. Printed by N. O. [Nicholas Okes] for Thomas Walkley, and are to be sold at his shop, at the Eagle and Child, in Brittans Bursse, 1622."

One year later, the play was included among the plays in the First Folio of Shakespeare's collected plays. However, the version in the Folio is rather different in length, and in wording: as the editors of the Folger edition explain: "The Folio play has about 160 lines that do not appear in the Quarto. Some of these cluster together in quite extensive passages. The Folio also lacks a scattering of about a dozen lines or part-lines that are to be found in the Quarto. These two versions also differ from each other in their readings of numerous words.[15] Scholars differ in their explanation of these differences, and no consensus has emerged.[15] Kerrigan suggests that the 1623 Folio version of Othello and a number of other plays may have been cleaned-up relative to the Quarto to conform with the 1606 Act to Restrain Abuses, which made it an offence 'in any Stage-play, Interlude, Shew, Maygame, or Pageant, iestingly, and prophanely [to] speake, or vse the holy Name of God, or of Christ Iesus, or of the holy Ghost, or of the Trinitie'.[16] This is not incompatible with the suggestion that the Quarto is based on an early version of the play, whilst the Folio represents Shakespeare's revised version.[15] It may also be that the Quarto was cut in the printing house to meet a fixed number of pages.[2] Most modern editions are based on the longer Folio version, but often incorporate Quarto readings of words when the Folio text appears to be in error.[17] Quartos were also published in 1630, 1655, 1681, 1695, 1699 and 1705.

Themes

Jealousy

Othello is renowned amongst literary scholars for the way it portrays the human emotion of jealousy. Throughout the play, good-natured characters make rash decisions based on the jealousy that they feel, most notably Othello.

In the early acts, Othello is depicted as a typical heroic figure and holds admirable qualities, written with the intention of winning over the favour of the audience; however, as the play goes on, jealousy will manipulate his decisions and lead him into sin. While the majority of the evil that Othello carries out in the play can be cited as coming from Iago, it is jealousy that motivates him to perform wicked deeds. When Iago highlights the almost excessive amount of time that Cassio and his wife, Desdemona, are spending together, Othello becomes filled with rage and, following a series of events, will murder the one that he loves.

Shakespeare explores man's ugliest trait in this opus and perfectly represents the idea of the 'tragic hero' in Othello, who wins over the responders early on but proceeds to make bad, almost wicked, decisions that will make it harder for the audience to like him until his eventual undoing. This idea of the tragic hero is made clear through the utilisation of jealousy, one of the various notable themes present in Othello.

Iago versus Othello

Although its title suggests that the tragedy belongs primarily to Othello, Iago plays an important role in the plot. He reflects the archetypal villain and has the biggest share of the dialogue. In Othello, it is Iago who manipulates all other characters at will, controlling their movements and trapping them in an intricate net of lies. He achieves this by getting close to all characters and playing on their weaknesses while they refer to him as "honest" Iago, thus furthering his control over the characters. A. C. Bradley, and more recently Harold Bloom, have been major advocates of this interpretation.[18] Other critics, most notably in the later twentieth century (after F. R. Leavis), have focused on Othello.

Race

Although characters described as "Moors" appear in two other Shakespeare plays (Titus Andronicus and The Merchant of Venice), such characters were a rarity in contemporary theatre, and it was unknown for them to take centre stage.[20]

There is no consensus over Othello's ethnic origin. E. A. J. Honigmann, the editor of the Arden Shakespeare edition, concluded that Othello's race is ambiguous. "Renaissance representations of the Moor were vague, varied, inconsistent, and contradictory. As critics have established, the term 'Moor' referred to dark-skinned people in general, used interchangeably with terms such as 'African', 'Somali', 'Ethiopian', 'Negro', 'Arab', 'Berber', and even 'Indian' to designate a figure from Africa (or beyond)."[21][22] Various uses of the word black (for example, "Haply for I am black") are insufficient evidence for any accurate racial classification, Honigmann argues, since black could simply mean swarthy to Elizabethans. Iago twice uses the word Barbary or Barbarian to refer to Othello, seemingly referring to the Barbary coast inhabited by Berbers. Roderigo calls Othello "the thicklips", which seems to refer to Sub-Saharan African physiognomy, but Honigmann counters that, as these comments are all intended as insults by the characters, they need not be taken literally.[23]

However, Jyotsna Singh wrote that the opposition of Brabantio to Desdemona marrying Othello – a respected and honoured general – cannot make sense except in racial terms, citing the scene where Brabantio accuses Othello of using witchcraft to make his daughter fall in love with him, saying it is "unnatural" for Desdemona to desire Othello's "sooty bosom".[24] Singh argued that, since people with dark complexions are common in the Mediterranean area, a Venetian senator like Brabantio being opposed to Desdemona marrying Othello for merely being swarthy makes no sense, and that the character of Othello was intended to be black.[24]

Michael Neill, editor of The Oxford Shakespeare, notes that the earliest critical references to Othello's colour (Thomas Rymer's 1693 critique of the play, and the 1709 engraving in Nicholas Rowe's edition of Shakespeare) assume him to be Sub-Saharan, while the earliest known North African interpretation was not until Edmund Kean's production of 1814.[25] Honigmann discusses the view that Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun, Moorish ambassador of the Arab sultan of Barbary (Morocco) to Queen Elizabeth I in 1600, was one inspiration for Othello. He stayed with his retinue in London for several months and occasioned much discussion. While Shakespeare's play was written only a few years afterwards, Honigmann questions the view that ben Messaoud himself was a significant influence on it.[26]

Othello is referred to as a "Barbary horse" (1.1.113) and a "lascivious Moor" (1.1.127). In 3.3 he denounces Desdemona's supposed sin as being "black as mine own face". Desdemona's physical whiteness is otherwise presented in opposition to Othello's dark skin: 5.2 "that whiter skin of hers than snow". Iago tells Brabantio that "an old black ram / is tupping your white ewe" (1.1.88). In Elizabethan discourse, the word "black" could suggest various concepts that extended beyond the physical colour of skin, including a wide range of negative connotations.[28][29]

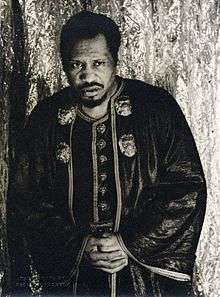

Othello was frequently performed as an Arab Moor during the 19th century. He was first played by a black man on the London stage in 1833 by the most important of the nineteenth-century Othellos, the African American Ira Aldridge who had been forced to leave his home country to make his career.[30] Regardless of what Shakespeare intended by calling Othello a "Moor" – whether he meant that Othello was a Muslim or a black man or both – in the 19th century and much of the 20th century, many critics tended to see the tragedy in racial terms, seeing interracial marriages as "aberrations" that could end badly.[31] Given this view of Othello, the play became especially controversial in apartheid-era South Africa where interracial marriages were banned and performances of Othello were discouraged.[32]

The first major screen production casting a black actor as Othello did not come until 1995, with Laurence Fishburne opposite Kenneth Branagh's Iago.[33] In the past, Othello would often have been portrayed by a white actor in blackface or in a black mask: more recent actors who chose to 'black up' include Ralph Richardson (1937); Orson Welles (1952); John Gielgud (1961); Laurence Olivier (1964); and Anthony Hopkins (1981).[33] Ground-breaking black American actor Paul Robeson played the role in three different productions between 1930 and 1959. The casting of the role comes with a political subtext. Patrick Stewart played the role alongside an otherwise all-black cast in the Shakespeare Theatre Company's 1997 staging of the play[34][35] and Thomas Thieme, also white, played Othello in a 2007 Munich Kammerspiele staging at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford. Michael Gambon also took the role in 1980 and 1991; their performances were critically acclaimed.[36][37] Carlo Rota, of Mediterranean (British Italian) heritage, played the character on Canadian television in 2008.[38]

The race of the title role is often seen as Shakespeare's way of isolating the character, culturally as well as visually, from the Venetian nobles and officers, and the isolation may seem more genuine when a black actor takes the role. But questions of race may not boil down to a simple decision of casting a single role. In 1979, Keith Fowler’s production of Othello mixed the races throughout the company. Produced by the American Revels Company at the Empire Theater (renamed the November Theater in 2011) in Richmond, Virginia, this production starred African American actor Clayton Corbin in the title role, with Henry K. Bal, a Hawaiian actor of mixed ethnicity, playing Iago. Othello’s army was composed of both black and white mercenaries. Iago’s wife, Emilia was played by the popular black actress Marie Goodman Hunter.[39] The 2016 production at the New York Theatre Workshop, directed by Sam Gold, also effectively used a mixed-race cast, starring English actors David Oyelowo as Othello and Daniel Craig as Iago. Desdemona was played by American actress Rachel Brosnahan, Cassio was played by Finn Wittrock, and Emilia was played by Marsha Stephanie Blake.

As the Protestant Reformation of England proclaimed the importance of pious, controlled behaviour in society, it was the tendency of the contemporary Englishman to displace society's "undesirable" qualities of barbarism, treachery, jealousy and libidinousness onto those who are considered "other".[40] The assumed characteristics of black men, or "the other", were both instigated and popularised by Renaissance dramas of the time; for example, the treachery of black men inherent to George Peele's The Battle of Alcazar (1588).[41] It has been argued that it is Othello's "otherness" which makes him so vulnerable to manipulation. Audiences of the time would expect Othello to be insecure about his race and the implied age gap between himself and Desdemona.

Religious and philosophical

The title "Moor" implies a religious "other" of North African or Middle Eastern descent. Though the actual racial definition of the term is murky, the implications are religious as well as racial.[42] Many critics have noted references to demonic possession throughout the play, especially in relation to Othello's seizure, a phenomenon often associated with possession in the popular consciousness of the day.[43] Thomas M. Vozar, in a 2012 article in Philosophy and Literature, suggests that the epileptic fit relates to the mind–body problem and the existence of the soul.[44]

The hero

There have been many differing views on the character of Othello over the years. A.C. Bradley calls Othello the "most romantic of all of Shakespeare's heroes" (by "hero" Bradley means protagonist) and "the greatest poet of them all". On the other hand, F.R. Leavis describes Othello as "egotistical". There are those who also take a less critical approach to the character of Othello such as William Hazlitt, who said: "the nature of the Moor is noble ... but his blood is of the most inflammable kind". Conversely, many scholars have seen Iago as the anti-hero of the piece. W. H. Auden, for example, observed that "any consideration of [the play] must be primarily occupied, not with its official hero, but with its villain".[45]

Performance history

Pre-20th century

Othello possesses an unusually detailed performance record. The first certainly known performance occurred on 1 November 1604, at Whitehall Palace in London, being mentioned in a Revels account on "Hallamas Day, being the first of Nouembar", 1604, when "the Kings Maiesties plaiers" performed "A Play in the Banketinge house at Whit Hall Called The Moor of Venis". The play is there attributed to "Shaxberd".[46] Subsequent performances took place on Monday, 30 April 1610 at the Globe Theatre, and at Oxford in September 1610.[47] On 22 November 1629, and on 6 May 1635, it played at the Blackfriars Theatre. Othello was also one of the twenty plays performed by the King's Men during the winter of 1612, in celebration of the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Frederick V, Elector Palatine.[48]

At the start of the Restoration era, on 11 October 1660, Samuel Pepys saw the play at the Cockpit Theatre. Nicholas Burt played the lead, with Charles Hart as Cassio; Walter Clun won fame for his Iago. Soon after, on 8 December 1660, Thomas Killigrew's new King's Company acted the play at their Vere Street theatre, with Margaret Hughes as Desdemona – probably the first time a professional actress appeared on a public stage in England.

It may be one index of the play's power that Othello was one of the very few Shakespearean plays that was never adapted and changed during the Restoration and the eighteenth century.[49]

As Shakespeare regained popularity among nineteenth-century French Romantics, poet, playwright, and novelist Alfred de Vigny created a French translation of Othello, titled Le More de Venise, which premiered at the Comédie-Française on 24 October 1829.

Famous nineteenth-century Othellos included Ira Aldridge, Edmund Kean, Edwin Forrest, and Tommaso Salvini, and outstanding Iagos were Edwin Booth and Henry Irving.

20th century

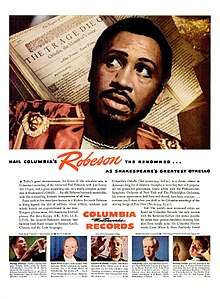

The most notable American production may be Margaret Webster's 1943 staging starring Paul Robeson as Othello and José Ferrer as Iago. This production was the first ever in America to feature a black actor playing Othello with an otherwise all-white cast (there had been all-black productions of the play before). It ran for 296 performances, almost twice as long as any other Shakespearean play ever produced on Broadway. Although it was never filmed, it was the first lengthy performance of a Shakespeare play released on records, first on a multi-record 78 RPM set and then on a 3-LP one. Robeson had first played the role in London in 1930 in a cast that included Peggy Ashcroft as Desdemona and Ralph Richardson as Roderigo,[50] and would return to it in 1959 at Stratford-upon-Avon with co-stars Mary Ure, Sam Wanamaker and Vanessa Redgrave. The critics had mixed reactions to the "flashy" 1959 production which included mid-western accents and rock-and roll drumbeats but gave Robeson primarily good reviews.[51] W. A. Darlington of The Daily Telegraph ranked Robeson's Othello as the best he had ever seen[52] while the Daily Express, which had for years before published consistently scathing articles about Robeson for his leftist views, praised his "strong and stately" performance (though in turn suggested it was a "triumph of presence not acting").[53]

Actors have alternated the roles of Iago and Othello in productions to stir audience interest since the nineteenth century. Two of the most notable examples of this role swap were William Charles Macready and Samuel Phelps at Drury Lane (1837) and Richard Burton and John Neville at The Old Vic (1955). When Edwin Booth's tour of England in 1880 was not well attended, Henry Irving invited Booth to alternate the roles of Othello and Iago with him in London. The stunt renewed interest in Booth's tour. James O'Neill also alternated the roles of Othello and Iago with Booth.

The American actor William Marshall performed the title role in at least six productions. His Othello was called by Harold Hobson of the London Sunday Times "the best Othello of our time,"[54] continuing:

...nobler than Tearle, more martial than Gielgud, more poetic than Valk. From his first entry, slender and magnificently tall, framed in a high Byzantine arch, clad in white samite, mystic, wonderful, a figure of Arabian romance and grace, to his last plunging of the knife into his stomach, Mr Marshall rode without faltering the play's enormous rhetoric, and at the end the house rose to him.[55]

Marshall also played Othello in a jazz musical version, Catch My Soul, with Jerry Lee Lewis as Iago, in Los Angeles in 1968.[56] His Othello was captured on record in 1964 with Jay Robinson as Iago and on video in 1981 with Ron Moody as Iago. The 1982 Broadway staging starred James Earl Jones as Othello and Christopher Plummer as Iago, who became the only actor to receive a Tony Award nomination for a performance in the play.

When Laurence Olivier gave his acclaimed performance of Othello at the Royal National Theatre in 1964, he had developed a case of stage fright that was so profound that when he was alone onstage, Frank Finlay (who was playing Iago) would have to stand offstage where Olivier could see him to settle his nerves.[57] This performance was recorded complete on LP, and filmed by popular demand in 1965 (according to a biography of Olivier, tickets for the stage production were notoriously hard to get). The film version still holds the record for the most Oscar nominations for acting ever given to a Shakespeare film – Olivier, Finlay, Maggie Smith (as Desdemona) and Joyce Redman (as Emilia, Iago's wife) were all nominated for Academy Awards. Olivier was among the last white actors to be greatly acclaimed as Othello, although the role continued to be played by such performers as Donald Sinden at the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1979–1980, Paul Scofield at the Royal National Theatre in 1980, Anthony Hopkins in the BBC Television Shakespeare production (1981), and Michael Gambon in a stage production at Scarborough directed by Alan Ayckbourn in 1990. Gambon had been in Olivier's earlier production. In an interview Gambon commented "I wasn't even the second gentleman in that. I didn't have any lines at all. I was at the back like that, standing for an hour. [It's] what I used to do – I had a metal helmet, I had an earplug, and we used to listen to The Archers. No one knew. All the line used to listen to The Archers. And then I went and played Othello myself at Birmingham Rep I was 27. Olivier sent me a telegram on the first night. He said, "Copy me." He said, "Do what I used to do." Olivier used to lower his voice for Othello so I did mine. He used to paint the big negro lips on. You couldn't do it today, you'd get shot. He had the complete negro face. And the hips. I did all that. I copied him exactly. Except I had a pony tail. I played him as an Arab. I stuck a pony tail on with a bell on the end of it. I thought that would be nice. Every time I moved my hair went wild."[58] British blacking-up for Othello ended with Gambon in 1990; however the Royal Shakespeare Company didn't run the play at all on the main Stratford stage until 1999, when Ray Fearon became the first black British actor to take the part, the first black man to play Othello with the RSC since Robeson.[59]

In 1997, Patrick Stewart took the role of Othello with the Shakespeare Theatre Company (Washington, D.C.) in a race-bending performance, in a "photo negative" production of a white Othello with an otherwise all-black cast. Stewart had wanted to play the title role since the age of 14, so he and director Jude Kelly inverted the play so Othello became a comment on a white man entering a black society.[34][35] The interpretation of the role is broadening, with theatre companies casting Othello as a woman or inverting the gender of the whole cast to explore gender questions in Shakespeare's text. Companies have also chosen to share the role between several actors during a performance.[60][61]

Canadian playwright Ann-Marie MacDonald's 1988 award-winning play Goodnight Desdemona (Good Morning Juliet) is a revision of Othello and Romeo and Juliet in which an academic deciphers a cryptic manuscript she believes to be the original source for the tragedies, and is transported into the plays themselves.[62]

21st century

Othello opened at the Donmar Warehouse in London on 4 December 2007, directed by Michael Grandage, with Chiwetel Ejiofor as Othello, Ewan McGregor as Iago, Tom Hiddleston as Cassio, Kelly Reilly as Desdemona and Michelle Fairley as Emilia. Ejiofor, Hiddleston and Fairley all received nominations for Laurence Olivier Awards, with Ejiofor winning. Stand-up comedian Lenny Henry played Othello in 2009 produced by Northern Broadsides in collaboration with West Yorkshire Playhouse.[63] In March 2016 the historian Onyeka produced a play entitled Young Othello, a fictional take on Othello's young life before the events of Shakespeare's play.[64][65] In June 2016, baritone and actor David Serero played the title role in a Moroccan adaptation featuring Judeo-Arabic songs and Verdi's opera version in New York.[66][67] In 2017, Ben Naylor directed the play for the Pop-up Globe in Auckland, with Māori actor Te Kohe Tuhaka in the title role, Jasmine Blackborow as Desdemona and Haakon Smestad as Iago.[68] The production transferred to Melbourne, Australia with another Maori actor, Regan Taylor, taking over the title role.[69]

In September 2013, a Tamil adaptation titled Othello, the Fall of a Warrior was directed and produced in Singapore by Subramanian Ganesh.[70]

Adaptations and cultural references

Othello as a literary character has appeared in many representations within popular culture over several centuries. There also have been over a dozen film adaptations of Othello.

References

- "Cinthioʹs Tale: The Source of Shakespeareʹs Othello" (PDF). St. Stephen's School.

- Shakespeare, William. Four Tragedies: Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth. Bantam Books, 1988.

- Young, John G., M.D. "Essay: What Is Creativity?". Adventures in Creativity: Multimedia Magazine. 1 (2). Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- "Virgil.org" (PDF). Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Shakespeare, William. Othello. Wordsworth Editions. 12. Retrieved from Google Books on 5 November 2010. ISBN 1-85326-018-5, 978-1-85326-018-6.

- Bevington, David and Bevington, Kate (translators). "Un Capitano Moro" in Four Tragedies: Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth. Bantam Books, 1988. pp. 371–387.

- Professor Nabil Matar (April 2004), Shakespeare and the Elizabethan Stage Moor, Sam Wanamaker Fellowship Lecture, Shakespeare's Globe Theatre (cf. Mayor of London (2006), Muslims in London, pp. 14–15, Greater London Authority)

- Black, Crofton (2002). "Leo Africanus's Descrittione dell'Africa and its sixteenth-century translations". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 65: 262–272. JSTOR 4135111.

- ""A Man of Two Worlds"". Archived from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- Lois Whitney, "Did Shakespeare Know Leo Africanus?" PMLA 37.3 (September 1922:470–483).

- McPherson, David (Autumn 1988). "Lewkenor's Venice and Its Sources". Renaissance Quarterly. University of Chicago Press. 41 (3): 459–466. doi:10.2307/2861757.

- Bate, Jonathan (2004). "Shakespeare's Islands". In Clayton, Tom; et al. (eds.). Shakespeare and the Mediterranean. University of Delaware Press. p. 291. ISBN 0-87413-816-7.

- Sanders, Norman (ed.). Othello (2003, rev. ed.), New Cambridge Shakespeare, p1.

- E. A. J. Honigmann (ed), Othello (1997), Arden Shakespeare, Appendix 1, pp. 344–350.

- Paul Westine and Barbara Mowat, eds. Othello, Folger Shakespeare Library edition (New York: WSP, 1993), p. xlv.

- John Kerrigan, Shakespeare's Binding Language, Oxford University Press (Oxford & New York: 2016)

- Paul Westine and Barbara Mowat, eds. Othello, Folger Shakespeare Library edition (New York: WSP, 1993), pp. xlv–xlvi.

- Shakespeare, William; Ruffiel, Burton (2005). Othello (Yale Shakespeare). Bloom, Harold. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10807-9.

- Bate, Jonathan; Rasmussen, Eric (2009). Othello. Basingstoke, England: Macmillan. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-230-57621-6.

- Dickson, Andrew (2016). The Globe Guide to Shakespeare. Profile Books. pp. 331, 334. ISBN 978-1-78125-634-3.

- Making More of the Moor: Aaron, Othello, and Renaissance Refashionings of Race. Emily C. Bartels

- "Moor, n2", The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edtn.

- E. A. J. Honigmann, ed. Othello. London: Thomas Nelson, 1997, p. 15.

- Singh, Jyotsna "Post-colonial criticism" pp. 492–507 from Shakespeare An Oxford Guide, ed. Stanley Wells & Lena Cowen Orlin, Oxford: OUP, 2003 p.493.

- Michael Neill, ed. Othello (Oxford University Press), 2006, pp. 45–47.

- Honigmann pp. 2–3.

- "Othello". Walters Art Museum.

- Doris Adler, "The Rhetoric of Black and White in Othello" Shakespeare Quarterly, 25 (1974)

- Oxford English Dictionary, 'Black', 1c.

- Dickson, Andrew (2016). The Globe Guide to Shakespeare. Profile Books. p. 342. ISBN 978-1-78125-634-3.

- Singh, Jyotsna "Post-colonial criticism" pp. 492–507 from Shakespeare An Oxford Guide, ed. Stanley Wells * Lena Cowen Orlin, Oxford: OUP, 2003 pp. 493–494.

- Singh, Jyotsna "Post-colonial criticism" pp. 492–507 from Shakespeare An Oxford Guide, ed. Stanley Wells * Lena Cowen Orlin, Oxford: OUP, 2003 pp. 494–495.

- Cartmell, Deborah (2000) Interpreting Shakespeare on screen Palgrave MacMillan pp. 72–77 ISBN 978-0-312-23393-8

- "The Issue of Race and Othello". Curtain up, DC. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Othello by William Shakespeare directed by Jude Kelly". The Shakespeare Theatre Company. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- Billington, Michael (5 April 2007). ""Black or white? Casting can be a grey area" Guardian article. 5 April 2007". Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Michael Billington (28 April 2006). "Othello (Theatre review) The Guardian Friday 28 April 2006". Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Othello". Cbc.ca. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Roy Proctor, "’Othello’ is Honest on Bare Stage," Richmond News Leader 10 February 1979

- Jones, Eldred (1971). Othello's Countrymen. Charlottesville: Univ of Virginia Press.

- Note also the character of Aaron the Moor in Shakespeare's play Titus Andronicus

- ""Moor, n3", The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edtn".

- Brownlow, F. W. (1979). "Samuel Harsnett and the Meaning of Othello's 'Suffocating Streams'". Philological Quarterly. 58: 107–115.

- Vozar, Thomas M. (2012). "Body-Mind Aporia in the Seizure of Othello". Philosophy and Literature. 36 (1): 183–186. doi:10.1353/phl.2012.0014.

- Auden, W. H. (1962). The Dyer's Hand (repr. ed.). London: Faber & Faber. p. 246. OCLC 247724574.

- Shakespeare, William. Four Tragedies. Bantam Books, 1988.

- Loomis, Catherine ed. (2002). William Shakespeare: A Documentary Volume, Vol. 263, Dictionary of Literary Biography, Detroit: Gale, 200–201.

- Potter, Lois (2002). Othello:Shakespeare in performance. Manchester University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7190-2726-0.

- F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; pp. 346–347.

- Wearing, J. P. (2014). The London Stage 1930-1939: A Calendar of Productions, Performers, and Personnel. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8108-9304-7. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Duberman, p. 477

- Duberman, p. 733, notes for pp. 475–478

- Daily Express, 10 April 1959

- Jet magazine, 30 June 2003

- The (London) Independent, 6 July 2003

- Christgau, Robert. Any Old Way You Choose It, ISBN 0-8154-1041-7

- Laurence Olivier, Confessions of an Actor, Simon and Schuster (1982) p. 262

- The Arts Desk – "theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Michael Gambon" – by Jasper Rees – 25 September 2010–2009 The Arts Desk Ltd. Website by 3B Digital, London, UK.

- Hugo Rifkind. "The Times 9 February 2004 "Black and white more show"". Entertainment.timesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Independent article 25 August 1993. "Edinburgh Festival"". Independent.co.uk. 25 August 1993. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- 5 October 2010 "The Docklands" Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia". Canadiantheatre.com. 10 February 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Shakespeare's Othello | Cast & Creative – Lenny Henry". Othellowestend.com. 11 November 2002. Archived from the original on 19 October 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Young Othello – The Voice". Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- "Young Othello – Good Reads". Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- http://www.theculturenews.com/#!DAVID-SERERO-starring-as-OTHELLO-in-a-Moroccan-Style-this-June-in-New-York/cmbz/57282b750cf2051007a270c2

- "Sephardic OTHELLO to Open in June at Center for Jewish History". Broadway World. 17 May 2016.

- "The Cast". www.popupglobe.co.nz. Pop-up Globe. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- "Othello". PopUpGlobe. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017.

- "William Shakespeare's Othello : the fall of a warrior, 19th–22nd September 2013, Goodman Arts Centre". National Library Board Singapore. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Othello |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Othello. |

- Othello at Project Gutenberg

- Othello Navigator – Includes the annotated text, a search engine, and scene summaries.

- Othello at the Internet Broadway Database – lists numerous productions.

- Othello at the British Library

.png)