Taifa

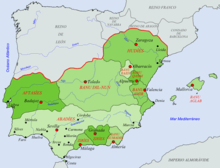

The taifas (singular taifa, from Arabic: طائفة ṭā'ifa, plural طوائف ṭawā'if, a party, band or faction) were the independent Muslim principalities of the Iberian Peninsula (modern Portugal and Spain), referred to by Muslims as al-Andalus, that emerged from the decline and fall of the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba between 1009 and 1031. They were a recurring feature of Andalusian history. Conquered by the Almoravids in the late 11th century, on its collapse many taifas re-appeared only to be subsumed by the Almohads. The fall of the latter resulted in a final flourishing of the taifas, but by the end of the 13th century only one remained, Granada, the rest being incorporated into the Christian states of the north.

Terminology

The Arabic term mulūk al-ṭawāʾif, meaning "kings of the territorial divisions"[1] or "party kings",[2] was originally used for the regional rulers of the Parthian Empire. This period was treated as an interlude between Alexander's conquest of Persia and the formation of the Sasanian Empire. The negative portrayal of the Parthian period by Muslim historians may have been inherited from Sasanian propaganda. In the 11th century, Ṣāʿid al-Andalusī first applied the term to the regional rulers who appeared after the collapse of Umayyad power in Spain, "whose condition was like that of the of mulūk al-ṭawāʾif the Persians". The phrase implied cultural decline.[1]

The corresponding term in Spanish is reyes de taifas ("kings of taifas"), by way of which the Arabic term has entered English (and French) usage.[3]

Rise

The origins of the taifas must be sought in the administrative division of the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba, as well in the ethnic division of the elite of this state, divided among Arabs, the more numerous Berbers, Iberian Muslims (known as Muladíes – a significant majority) and the Eastern European former slaves.

During the late 11th century the Christian rulers of the northern Iberian peninsula set out to take over the Muslim territories, defining them as Christian lands that had been conquered by infidels, and now needed to be reconquered. The caliphate of Cordova, at this time among the richest and most powerful states in Europe, underwent civil war, known as fitna. As a result, it "broke into taifas, small rival emirates fighting among themselves".[4]

However, the political decline and chaos was not immediately followed by cultural decline. To the contrary, intense intellectual and literary activity grew in some of the larger taifas.

There was a second period when taifas arose, toward the middle of the 12th century, when the Almoravid rulers were in decline.

During the heyday of the taifas, in the 11th century and again in the mid 12th century, their emirs (rulers) competed among themselves, not only militarily but also for cultural prestige. They tried to recruit the most famous poets and artisans.

Decline

Reversing the trend of the Umayyad period, when the Christian kingdoms of the north often had to pay tribute to the Caliph, the disintegration of the Caliphate left the rival Muslim kingdoms much weaker than their Christian counterparts, particularly the Castilian–Leonese monarchy, and had to submit to them, paying tributes known as parias.

Due to their military weakness, taifa princes appealed for North African warriors to come fight Christian kings on two occasions. The Almoravid dynasty was invited after the fall of Toledo (1085), and the Almohad Caliphate after the fall of Lisbon (1147). These warriors did not in fact help the taifa emirs but rather annexed their lands to their own North African empires.

Taifas often hired Christian mercenaries to fight neighbouring realms (both Christian and Muslim). The most dynamic taifa, which conquered most of its neighbours before the Almoravid invasion, was Seville. Zaragoza was also very powerful and expansive, but inhibited by the neighbouring Christian states of the Pyrenees. Zaragoza, Toledo, and Badajoz had previously been the border military districts of the Caliphate.

List of taifas

First period (11th century)

After the fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba in 1031 about 33 independent taifas emerged out the civil war and conflict in Al-Andalus. The strongest and largest taifas in this first period (11th century) were the Taifa of Zaragoza, Taifa of Toledo, Taifa of Badajoz and the Taifa of Seville. The only taifa which conquered most of its weak neighbours was the Taifa of Seville under the Abbadid dynasty.

Al-Tagr Al-Adna (Central Portugal)

This region includes the Centro and Lisboa region of Portugal and Extremadura region of Spain.

Al-Garb (Southern Portugal)

This region includes the Alentejo and Algarve region of Portugal.

- Mértola 1033–1044 (Tayfurid Dynasty); 1044–1091 (to Seville)

- Saltés and Huelva 1012/1013–1051/1053 (Bakrid Dynasty); 1051–1091 (to Seville)

- Santa Maria do Algarve 1018–1051 (Harunid Dynasty); 1051–1091 (to Seville)

- Silves: 1027–1063 (Muzaymid Dynasty); 1063–1091 (to Seville)

Al-Tagr Al-Awsat (Central Spain)

This region includes the Madrid region and the provinces of Toledo and Guadalajara of Spain.

Al-Andalus (Southern Spain)

This region includes the autonomous region of Andalucia in Spain

- Algeciras: 1035–1058 (to Seville)

- Arcos: 1011–1068 (to Seville)

- Carmona: 1013–1091 (to Almoravids)

- Ceuta: 1061–1084 (to Granada)

- Córdoba: 1031–1091 (to Seville)

- Granada: 1013–1090 (to Almoravids)

- Málaga: 1026–1057/1058 (to Granada); 1073–1090 (to Almoravids)

- Morón: 1013–1066 (to Seville)

- Niebla: 1023/1024–1091 (to Seville)

- Ronda: 1039/1040–1065 (to Seville)

- Seville: 1023–1091 (to Almoravids)

Al-Tagr Al-A'la (Aragon and Catalonia)

This region only includes the provinces of Teruel, Zaragoza and Tarragona of Spain.

- Albarracín: 1011–1104 (to Almoravids)

- Alpuente: 1009–1106 (to Almoravids)

- Rueda: 1118–1130 (to Aragon)

- Tortosa: 1039–1060 (to Zaragoza); 1081/1082–1092 (to Denia)

- Zaragoza: 1018–1046 (to Banu Tujib; then to Banu Hud); 1046–1110 (to Almoravids; in 1118 to Aragon)

Al-Xarq (Eastern Spain)

This region includes the region of Valencia, Murcia and Baleares.

- Almería: 1011–1091 (to Almoravids)

- Denia: 1010/1012–1076 (to Zaragoza)

- Jérica: 11th century (to Toledo)

- Lorca: 1051–1091 (to Almoravids)

- Majorca: 1018–1203 (to Almohads)

- Molina: ?–1100 (to Aragon)

- Murcia: 1011/1012–1065 (to Valencia)

- Murviedro and Sagunto: 1086–1092 (to Almoravids)

- Segorbe: 1065–1075 (to Almoravids)

- Valencia: 1010/1011–1094 (to El Cid, nominally vassal of Castile but allied to Banu Hud)

| History of Al-Andalus |

|---|

|

Muslim conquest (711–732) |

|

Umayyads of Córdoba (756–1031) |

|

|

First Taifa period (1009–1110) |

|

Almoravid rule (1085–1145) |

|

Second Taifa period (1140–1203) |

|

Almohad rule (1147–1238) |

|

Third Taifa period (1232–1287) |

|

Emirate of Granada (1238–1492) |

| Related articles |

Second period (12th century)

- Almería: 1145–1147 (briefly to Castile and then to Almohads)

- Arcos: 1143 (to Almohads)

- Badajoz: 1145–1150 (to Almohads)

- Beja and Évora: 1144–1150 (to Almohads)

- Carmona: dates and destiny uncertain or unknown

- Constantina and Hornachuelos: dates and destiny uncertain or unknown

- Granada: 1145 (to Almohads)

- Guadix and Baza: 1145–1151 (to Murcia)

- Jaén: 1145–1159 (to Murcia); 1168 (to Almohads)

- Jerez: 1145 (to Almohads)

- Málaga: 1145–1153 (to Almohads)

- Mértola: 1144–1145 (to Badajoz)

- Murcia: 1145 (to Valencia); 1147–1172 (to Almohads)

- Niebla: 1145–1150? (to Almohads)

- Purchena: dates and destiny uncertain or unknown

- Ronda: 1145 (to Almoravids)

- Santarém: ?–1147 (to Portugal)

- Segura: 1147–? (destiny unknown)

- Silves: 1144–1155 (to Almohads)

- Tavira: dates and destiny uncertain or unknown

- Tejada: 1145–1150 (to Almohads)

- Valencia: 1145–1172 (to Almohads)

Third period (13th century)

- Arjona: 1232–1244 (to Castile)

- Baeza: 1224–1226 (to Castile)

- Ceuta: 1233–1236 (to Almohads), 1249–1305 (to Marinids)

- Denia: 1224–1227 (to Aragon)

- Lorca: 1240–1265 (to Castile)

- Menorca: 1228–1287 (to Aragon)

- Murcia: 1228–1266 (to Castile)

- Niebla: 1234–1262 (to Castile)

- Orihuela: 1239/1240–1249/1250 (to Murcia or Castile)

- Valencia: 1228/1229–1238 (to Aragon)

Additionally, but not usually considered taifas, are:

References

- M. Morony (1993). "Mulūk al-Ṭawāʾif, 2. In Pre-Islamic Persia". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 551–552. ISBN 90-04-09419-9.

- D. J. Wasserstein (1985), The Rise and Fall of the Party-kings: Politics and Society in Islamic Spain, 1002–1086, Princeton University Press.

- D. J. Wasserstein (1993). "Mulūk al-Ṭawāʾif, 2. In Muslim Spain". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 552–554. ISBN 90-04-09419-9.

- Tolan, John (2013). Europe and the Islamic World: A History. Princeton: Princeton University press. p. 40, 39-40.