Hagar

Hagar (Hebrew: הָגָר, Hāḡār, of uncertain origin;[1] Arabic: هَاجَر Hājar; Greek: Ἁγάρ, Hagár; Latin: Agar) is a biblical person in the Book of Genesis. She was an Ancient Egyptian servant of Sarah,[2] who gave her to Abraham to bear a child. The product of the union was Abraham's firstborn, Ishmael, the progenitor of the Ishmaelites Arabians. Various commentators have connected her to the Hagrites (sons of Agar), perhaps claiming her as their eponymous ancestor.[3][4][5][6]

Hagar | |

|---|---|

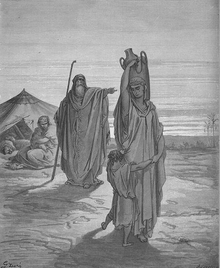

Expulsion of Ishmael and His Egyptian Mother, by Gustave Doré | |

| Born | |

| Died | Hebron or The land that is now, Mecca (in Islamic tradition) |

| Other names | Hājar |

| Occupation | Housewife |

| Spouse(s) | Abraham |

| Children | Ishmael (son of Abraham) |

| Relatives | Nebaioth, Mibsam, Dumah, Jetur, Naphish, Mishma, Basemath, Hadad, Tema, Massa, Adbeel, Kedemah, Kedar (all grandchildren) |

The name of the Egyptian servant Hagar is documented in the Book of Genesis; she is acknowledged in all Abrahamic religions. Hagar is alluded to in the Quran, and Islam acknowledges her as Abraham's second wife. According to Islamic tradition, Hagar the Egyptian is named as the "Grand Mother of Arabians" and her husband Abraham the Mesopotamian as the "Grand Father of Arabians".

Hagar in Genesis

This is a summary of the account of Hagar from Genesis 16 and 21.

Hagar and Abraham

Hagar was the Egyptian servant of Sarah, Abraham's wife. Sarah had been barren for a long time and sought a way to fulfill God's promise to Abraham that Abraham would be father of many nations, especially since they were getting older, so she offered Hagar to Abraham as a second wife.[7]

Hagar became pregnant, and tension arose between the two women. Sarah complained to Abraham, and treated Hagar harshly, and Hagar ran away.[8]

Hagar fled into the desert on her way to Shur. At a spring en route, an angel appeared to Hagar, who instructed her to return to Sarah, so that she may bear a child who "shall be a wild ass of a man: his hand shall be against every man, and every man's hand against him; and he shall dwell in the face of all his brethren" (Genesis 16:12). Then she was told to call her son Ishmael. Afterward, Hagar referred to God as "El Roi".[9] She then returned to Abraham and Sarah, and soon gave birth to a son, whom she named as the angel had instructed.[10]

Hagar cast out

Later, Sarah gave birth to Isaac, and the tension between the women returned. At a celebration after Isaac was weaned, Sarah found the teenage Ishmael mocking her son. She was so upset by it that she demanded that Abraham send Hagar and her son away. She declared that Ishmael would not share in Isaac's inheritance. Abraham was greatly distressed but God told Abraham to do as his wife commanded because God's promise would be carried out through Isaac; Ishmael would be made into a great nation as well because he was Abraham's offspring.[11]

Early the next morning, Abraham brought Hagar and Ishmael out together. Abraham gave Hagar bread and water then sent them into the wilderness of Beersheba. She and her son wandered aimlessly until their water was completely consumed. In a moment of despair, she burst into tears. God heard her and her son crying and came to rescue them.[12]

The angel opened Hagar's eyes and she saw a well of water. He also told Hagar that God would "make a great nation" of Ishmael.[12]

Hagar found her son a wife from Egypt and they settled in the Desert of Paran.[13]

Religious views

Baha'i traditions

According to the Baha'i Faith, the Báb was a descendant of Abraham and Hagar,[14] and God made a promise to spread Abraham's seed. The Baha'i Publishing House released a text on the wives and concubines of Abraham and traces their lineage to five different religions.[15]

Christianity

In the New Testament, Paul the Apostle made Hagar's experience an allegory of the difference between law and grace in his Epistle to the Galatians chapter 4 (Galatians 4:21–31).[16] Paul links the laws of the Torah, given on Mount Sinai, to the bondage of the Israelite people, implying that it was signified by Hagar's condition as a bondswoman, while the "free" heavenly Jerusalem is signified by Sarah and her child. The Biblical Mount Sinai has been referred to as "Agar", possibly named after Hagar.[17]

Augustine of Hippo referred to Hagar as symbolizing an "earthly city", or sinful condition of humanity: "In the earthly city (symbolised by Hagar) ... we find two things, its own obvious presence and the symbolic presence of the heavenly city. New citizens are begotten to the earthly city by nature vitiated by sin but to the heavenly city by grace freeing nature from sin." (The City of God 15:2) This view was expounded on by medieval theologians such as Thomas Aquinas and John Wycliffe. The latter compared the children of Sarah to the redeemed, and those of Hagar to the unredeemed, who are "carnal by nature and mere exiles".[18]

The story of Hagar demonstrates that survival is possible even under harshest conditions.[19]

Islam

Hājar or Haajar (Arabic: هاجر), is the Arabic name used to identify the wife of Ibrāhīm (Abraham) and the mother of Ismā'īl (Ishmael). Although not mentioned by name in the Qur'an, she is referenced and alluded to via the story of her husband. She is a revered woman in the Islamic faith.

According to Muslim belief, she was the Egyptian handmaiden of Ibrāhīm's first wife Sara (Sarah). She eventually settled in the Desert of Paran with her son Ismā'īl. Hājar is honoured as an especially important matriarch of monotheism, as it was through Ismā'īl that Muhammad would come.

Neither Sara nor Hājar are mentioned by name in the Qur'an, but the story is traditionally understood to be referred to in a line from Ibrāhīm's prayer in Sura Ibrahim (14:37): "I have settled some of my family in a barren valley near your Sacred House."[20] While Hājar is not named, the reader lives Hājar's predicament indirectly through the eyes of Ibrāhīm.[21] She is also frequently mentioned in the books of hadiths.

According to the Qisas Al-Anbiya, a collection of tales about the prophets, Hājar was the daughter of the King of Maghreb, a descendant of Salih. Her father was killed by Pharaoh Dhu l-'arsh and she was captured and taken as a slave. Later, because of her royal blood, she was made mistress of the female slaves and given access to all of Pharaoh's wealth. Upon conversion to Ibrāhīm's faith, the Pharaoh gave Hājar to Sara who gave her to Ibrāhīm. In this account, the name "Hājar" (called Hajar in Arabic) comes from Ha ajruka, Arabic for "here is your recompense".[21]

According to another tradition, Hājar was the daughter of the Egyptian king, who gave her to Ibrāhīm as a wife, thinking Sara was his sister.[22] According to Ibn Abbas, Ismā'īl's birth to Hājar caused strife between her and Sara, who was still barren. Ibrāhīm brought Hājar and their son to a land called Paran-aram or (Faran in Arabic, in latter days held to be the land surrounding Mecca).[23] The objective of this journey was to "resettle" rather than "expel" Hājar.[21] Ibrāhīm left Hājar and Ismā'īl under a tree and provided them with water.[23] Hājar, learning that God had ordered Ibrāhīm to leave her in the desert of Paran, respected his decision.[22] The Muslim belief is that God tested Ibrāhīm by ordering this task.[24]

Hājar soon ran out of water, and Ismā'īl, an infant by that time, began to cry from hunger/thirst. Hājar panicked and ran between two nearby hills, Al-Safa and Al-Marwah, repeatedly in search for water. After her seventh run, an angel appeared over the location of the Zamzam and then hit the ground with his heel (or his wing) and caused a miraculous well to spring out of the ground. This is called the Zamzam Well and is located a few metres from the Kaaba in Mecca.[23]

The incident[25] of her running between the Al-Safa and Al-Marwah hills is remembered by Muslims when they perform their pilgrimage (Hajj) at Mecca. Part of the pilgrimage is to run seven times between the hills, in commemoration of Hājar's courage and faith in God as she searched for water in the desert (which is believed to have then miraculously appeared from the Zamzam Well), and to symbolize the celebration of motherhood in Islam. To complete the task, some Muslims also drink from the Zamzam Well and take some of the water back home from pilgrimage in memory of Hājar.[26]

Rabbinical commentary

Rabbinical commentators asserted that Hagar was Pharaoh's daughter. The midrash Genesis Rabbah states it was when Sarah was in Pharaoh's harem that he gave her his daughter Hagar as servant, saying: "It is better that my daughter should be a servant in the house of such a woman than mistress in another house". Sarah treated Hagar well, and induced women who came to visit her to visit Hagar also. However Hagar, when pregnant by Abraham, began to act superciliously toward Sarah, provoking the latter to treat her harshly, to impose heavy work upon her, and even to strike her (ib. 16:9).[27]

Some Jewish commentators identify Hagar with Keturah (Aramaic: קְטוּרָה Qəṭurɔh), the woman Abraham married after the death of Sarah, stating that Abraham sought her out after Sarah's death. It is suggested that Keturah was Hagar's personal name, and that "Hagar" was a descriptive label meaning "stranger".[28][29][30] This interpretation is discussed in the Midrash[31] and is supported by Rashi, Judah Loew ben Bezalel, Shlomo Ephraim Luntschitz, and Obadiah ben Abraham Bartenura. Rashi argues that "Keturah" was a name given to Hagar because her deeds were as beautiful as incense (hence: ketores), and/or that she remained chaste from the time she was separated from Abraham—קְטוּרָה derives from the Aramaic word "restrained". The contrary view (that Keturah was someone other than Hagar) is advocated by the Rashbam, Abraham ibn Ezra, David Kimhi, and Nachmanides. They were listed as two different people in the genealogies in 1 Chronicles 1:29–33.

Arts and literature

Many artists have painted scenes from the story of Hagar and Ismael in the desert, including Pieter Lastman, Gustave Doré, Frederick Goodall and James Eckford Lauder. William Shakespeare refers to Hagar in The Merchant of Venice Act II Scene 5 line 40 when Shylock says "What says that fool of Hagar's offspring, ha?" This line refers to the character Launcelot, whom Shylock is insulting by comparing him to the outcast Ishmael. It also reverses the conventional Christian interpretation by portraying the Christian character as the outcast.[18]

Hagar's destitution and desperation are used as an excuse for criminality by characters in the work of Daniel Defoe, such as Moll Flanders, and the conventional view of Hagar as the mother of outcasts is repeated in Samuel Taylor Coleridge's play Zapolya, whose heroine is assured that she is "no Hagar's offspring; thou art the rightful heir to an appointed king."[18]

In the nineteenth century a more sympathetic portrayal became prominent, especially in America. Edmonia Lewis, the early African-American and Native American sculptor, made Hagar the subject of one of her most well-known works. She said it was inspired by "strong sympathy for all women who have struggled and suffered".[32] In novels and poems Hagar herself, or characters named Hagar, were depicted as unjustly suffering exiles. These include the long dramatic poem Hagar by Eliza Jane Poitevent Nicholson (pen name Pearl Rivers), president of the National Woman's Press Association; Hagar in the Wilderness by Nathaniel Parker Willis, the highest-paid magazine writer of his day; and Hagar's Farewell by Augusta Moore.[18] In 1913 this was joined by the overtly feminist novel Hagar,[33] by the American Southern socialist and suffragist Mary Johnston's.[34] Hall Caine gave the name A Son of Hagar to 1885 book set in contemporary England and dealing with the theme of illegitimacy.

A similarly sympathetic view prevails in more recent literature. The novel The Stone Angel by Margaret Laurence has a protagonist named Hagar married to a man named Bram, whose life story loosely imitates that of the biblical Hagar. A character named Hagar is prominently featured in Toni Morrison's novel Song of Solomon, which features numerous Biblical themes and allusions. In the 1979 novel Kindred, by Octavia Butler, the protagonist Dana has an ancestor named Hagar (born into slavery) whom we meet towards the end of the novel, as part of Dana's time travel back to Maryland in the 1800s. Hagar is mentioned briefly in Salman Rushdie's controversial novel The Satanic Verses, where Mecca is replaced with 'Jahilia', a desert village built on sand and served by Hagar's spring. Hagar is mentioned, along with Bilhah and Zilpah, in Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale, a dystopian novel which centres around the women whose duty it is to produce children for their masters, assuming the place of their wives in a rape ceremony based upon the biblical passage. In the recent book of nonfiction, The Woman Who Named God: Abraham's Dilemma and the Birth of Three Faiths, by Charlotte Gordon provides an account of Hagar's life from the perspectives of the three monotheistic religions, Islam, Judaism, and Christianity.

Contemporary influence

Israel

Since the 1970s, the custom has arisen of giving the name "Hagar" to newborn female babies. The giving of this name is often taken as a controversial political act, marking the parents as being supporters of reconciliation with the Palestinians and Arab World, and is frowned upon by many, including nationalists and the religious. The connotations of the name were represented by the founding of the Israeli journal Hagar: Studies in Culture, Polity and Identities in 2000.[35]

African Americans

Several black American feminists have written about Hagar, comparing her story to those of slaves in American history. Wilma Bailey, in an article entitled "Hagar: A Model for an Anabaptist Feminist", refers to her as a "maidservant" and "slave". She sees Hagar as a model of "power, skills, strength and drive". In the article "A Mistress, A Maid, and No Mercy", Renita J. Weems argues that the relationship between Sarah and Hagar exhibits "ethnic prejudice exacerbated by economic and social exploitation".[36]

Assisted reproduction

Hagar bearing a child for an infertile woman is an example of what is now called surrogacy or contractual gestation. Critics of this and other assisted reproductive technologies have used Hagar in their analysis. As early as 1988, Anna Goldman-Amirav in Reproductive and Genetic Engineering wrote of Hagar within "the Biblical 'battle of the wombs' [which] lay the foundation for the view of women, fertility, and sexuality in the patriarchal society".[37]

Family tree

| Terah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sarah[38] | Abraham | Hagar | Haran | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nahor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ishmael | Milcah | Lot | Iscah | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ishmaelites | 7 sons[39] | Bethuel | 1st daughter | 2nd daughter | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isaac | Rebecca | Laban | Moabites | Ammonites | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Esau | Jacob | Rachel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bilhah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Edomites | Zilpah | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Reuben 2. Simeon 3. Levi 4. Judah 9. Issachar 10. Zebulun Dinah (daughter) | 7. Gad 8. Asher | 5. Dan 6. Naphtali | 11. Joseph 12. Benjamin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- John L. Mckenzie (October 1995). The Dictionary Of The Bible. Simon and Schuster. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-684-81913-6.

- Douglas, J. D.; Merrill C. Tenney (eds.). Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Moisés Silva revisions (Rev. ed.). Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan. p. 560. ISBN 0310229839.

- Theodor Nöldeke (1899). "Hagar". In T. K. Cheyne; J. Shutherland Black (eds.). Encyclopaedia Biblica: A Critical Dictionary of the Literary, Political, and Religious History, the Archaeology, Geography, and Natural History of the Bible. 2, E–K. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Paul K. Hooker (2001). First and Second Chronicles. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-664-25591-6.

- Keith Bodner (29 August 2013). The Artistic Dimension: Literary Explorations of the Hebrew Bible. A&C Black. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-567-44262-8.

- Bruce K. Waltke (22 November 2016). Genesis: A Commentary. Zondervan. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-310-53102-9.

- Genesis 16:1-3

- Genesis 16:4-6

- 13 And she called the name of the LORD that spoke unto her, Thou art a God of seeing; for she said: 'Have I even here seen Him that seeth Me?' Genesis 16:13

- Genesis 16:7–16

- Genesis 21:9–13

- Genesis 21:18

- Genesis 21:14–21

- Apocalypse Secrets: Baha'i Interpretation of the Book of Revelation, p. 219, John Able (2011)

- Spirit of Faith: The Oneness of Humanity, p. 142, Baha'i Publishing (2011)

- Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 2011, p. 561

- Charles Forster (1844). The Historical Geography of Arabia, Duncan and Malcolm, p. 182.

- Jeffrey, David L., A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1992, p. 326 ISBN 0-8028-3634-8

- Susanne Scholz, "Gender, Class, and Androcentric Compliance in the Rapes of Enslaved Women in the Hebrew Bible", Lectio Difficilior (European Electronic Journal for Feminist Exegisis), 1/2004 (see especially section "The Story of Hagar (Genesis 16:1–16; 21:9–21)".

- Barbara Freyer Stowasser, Women in the Qur'an, Traditions, and Interpretation, New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 47.

- Fatani, Afnan H. (2006). "Hajar". In Leaman, Oliver (ed.). The Qur'an: an encyclopedia. London: Routeledge. pp. 234–36.

- 'Aishah 'Abd al-Rahman, Anthony Calderbank (1999). "Islam and the New Woman/ ﺍﻹﺳﻼﻡ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺮﺃﺓ ﺍﻟﺠﺪﻳﺪﺓ". Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics (19): 200.

- Firestone, Reuven (1992). "Ibrāhīm's Journey to Mecca in Islamic Exegesis: A Form-Critical Study of a Tradition". Studia Islamica (76): 15–18.

- Schussman, Aviva (1998). "The Legitimacy and Nature of Mawid al-Nabī: (Analysis of a Fatwā)". Islamic Law and Society. 5 (2): 218. doi:10.1163/1568519982599535.

- Muhammad, Martin Lings, Chapter 1. The House of God, Suhail Academy Publishing

- Delaney, Carol (August 1990). "The hajj: Sacred and Secular". American Ethnologist. 17 (3): 515. doi:10.1525/ae.1990.17.3.02a00060.

- "Jewish Encyclopedia, Hagar". Jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- "The Return of Hagar", commentary on Parshat Chayei Sarah, Chabad.

- "Who Was Ketura?", Bar-Ilan University's Parashat Hashavua Study Center, 2003.

- "Parshat Chayei Sarah" Archived 2008-11-13 at the Wayback Machine, Torah Insights, Orthodox Union, 2002.

- Bereshit Rabbah 61:4.

- Robinson, Hilary (2001-10-08). Feminism-art-theory: an anthology, 1968–2000. Books.google.co.uk. p. 230. ISBN 9780631208501. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- HAGAR. By Mary Johnston. Houghton Mifflin Company. (1913-11-02). "NYT review of Hagar by Johnston" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- Mary Johnston, Suffragist Marjorie Spruill Wheeler The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Vol. 100, No. 1, "Working out Her Destiny": Virginia Women's History (Jan., 1992), pp. 99–118 (article consists of 20 pages), published by Virginia Historical Society

- Oren Yiftachel, Launching Hagar: Marginality, Beer-Sheva, Critique Retrieved 2015-10-16

- Bailey, Wilma Ann Black and Jewish women consider Hagar, Encounter, Winter 2002

- Goldman-Amirav, Anna (1988). "Behold, the Lord Hath Restrained Me from Bearing" Archived 2011-02-19 at the Wayback Machine, Reproductive and Genetic Engineering: Journal of International Feminist Analysis Volume 1 Number 3.

- Genesis 20:12: Sarah was the half–sister of Abraham.

- Genesis 22:21-22: Uz, Buz, Kemuel, Chesed, Hazo, Pildash, and Jidlaph